Case Studies

Case study on anger management.

A. is an eight-year-old boy who attends a special school for children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. He has a diagnosis of autism.

Case study on Anxiety

B. is a fourteen year old girl and attends an autism unit within a mainstream school. She is very anxious and can be negative about her achievements and talents.

Case study on Class/Homework

C. is a twelve year old boy who is at secondary school. He is doing well at school but finds homework stressful.

Case study on Concentration & Attention

D. is a six year old boy who attends a mainstream primary school. He has a diagnosis of autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Case study on Emotional Regulation

E. is a ten year old boy who attends a social communication class within a mainstream school.

Case study on Group Work

G. is a ten year old boy with autism, he has recently moved to a special school setting. He previously attended a mainstream school and spent a lot of his time in an individual classroom due to behavioural difficulties.

Case study on Teenage Years

I. is 15 years old. He has a diagnosis of autism and attends a mainstream post primary school. He enjoys Art, ICT and Mathematics and has been provided with a classroom assistant for 20 hours per week.

Case study on Time Management

J. is an 18 year old student at Post Primary.

Case study on Transitions

K. is six years old and attends a special school. He has difficulties with transitions which cause him stress.

Book Appointment

- Autism Treatment

- Behavior Problems

- Mental Retardation

- Parental Guidance

- Cerebral Palsy

- Learning Disabilities

- Poor Memory

- Down Syndrome

- Sensory Processing Disorder

- Testimonials

A Case Study of Autism: Paul, 3 Years Old

- Autism Blog

- A Case Study of Autism:…

Arun was brought for consultation with Dr. A M Reddy by his parents. He was about 4 years old, the second child to the parents. Even while he was being brought into the room, we could hear his loud wailing. It took some time for the child to calm down and later we could observe that the child was very restless. He was running around the room, pulling down cushions and generally creating chaos in the room and mother was quite harried in trying to control him. He was diagnosed with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder).

What is ASD?

Autism or Mutinism as it was earlier known was thought primarily to affect communication skills but with more studies, it was understood that autistic children display a wide range of symptoms, hence the word “spectrum” was added to Autism disorder. Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder which affects a person’s social behavior and communication skills.

Why it occurs?

The exact reason why ASD occurs is not known but many risk factors have been identified like age of the parents, poor ovulation, infections or exposures to harmful chemicals or radiation during pregnancy, thyroid, diabetes type of hormonal disorders, birth injuries, infections in childhood, vaccinations, etc.

What are its symptoms?

As its name suggests, ASD displays a myriad of symptoms but some of the common symptoms of ASD is lack of speech. While some children have no speech, in some children speech that was developed before may regress. Many of them do not prefer to mingle with children of their age group. Repetitive action, physical restlessness, inability to understand emotions, mood swings like sudden bouts of excitement, crying without any reason, are few symptoms displayed by many autistic children.

Aggressive behaviors like self-harming, head-banging, tantrum-throwing, biting/pushing others, destructiveness, can be displayed by few. Response to name call, having sustained eye contact, unable to understand commands, stereotypical actions and stimming are some of the common symptoms exhibited by many.

Coming back to the case of Arun, a detailed case history was noted down by our doctors, a summary of which is given below.

He is the second child and the age difference between both the siblings is seven years. After the first child was born, the mother developed hypothyroidism for which she was on thyroxine 50 mcg daily tablets. No history of abortions or contraceptive use was reported. Father was apparently healthy. The age of the parents was 35 and 38 years respectively during conception. She conceived naturally and pregnancy was apparently uneventful. But on deeper probing few differences were found out between both the pregnancies.

While during the first pregnancy the parents were in India, but during second there were in the United States. She was advised to continue with the same dosage of thyroxine and during 6-7 months of the pregnancy, she was given flu and T Dap vaccine. The child was born of emergency C – section as the water broke early. The birth cry was normal and seemingly the child was progressing well but after his first birthday, the child had a bout of severe gastrointestinal infection when they visited India where he was hospitalized for three days and given medicines.

Parents were worried that he seems to put everything in his mouth and his favorite items were paper, cloth, wall plaster. His demands have to be met, else he used to become very upset. Emotional connectivity towards parents was less. He would not follow simple commands and it was becoming increasingly difficult for the parents to manage him. With therapies, his eye contact improved a little and was able to follow a few simple commands but the progress was slow.

He was a picky eater and liked crunchy foods. His bowels were constipated and he was not yet toilet trained. He was given Cuprum Sulph 10 M and was kept on regular follow up.

On the next visit to Dr. A M Reddy Autism Center , the parents complained that their child developed itching on the skin but his restlessness reduced slightly. The medication was continued for about three months during which the child’s anger reduced by 30%, his eye contact improved and he was no longer constipated. His itching too reduced in the meanwhile. A second dose was repeated and about six to seven months of treatment, he started saying few words, tantrum-throwing reduced and his habit of putting everything in the mouth was gone.

The dose was repeated in 50M potency. After about a year and half of treatment, he started interactive communication, giving relevant answers to questions and was doing much better. On the advice of Dr. A M Reddy, they placed him in normal school and he is doing well.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post comment

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, “i just want to stay out there all day”: a case study of two special educators and five autistic children learning outside at school.

- 1 Department of Education and Wellness, Elon University, Elon, NC, United States

- 2 Department of Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

School is often stressful for autistic students. Similarly, special educators are susceptible to burnout because of the unique demands of their jobs. There is ample evidence that spending time outside, particularly in nature, has many positive effects on mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing. In this case study of two special educators and five autistic students in a social skills group at an elementary school in the southeastern United States, we sought to identify the effects of moving the class outside several times per week. Findings indicated that while there were challenges, the autistic children experienced numerous affordances that supported development toward achieving Individualized Education Plan goals. Moreover, there were also notable positive effects for the special educators. We found that even with little prior experience, learning outside is possible and beneficial to everyone involved.

Introduction

The first time Jacob, an autistic 1 elementary student with selective mutism, ventured into an outdoor environment at his rural school, he spoke to his friend while they were in the midst of an activity. His special education teachers were shocked. They told us they had never heard him verbalize anything due to selective mutism, an anxiety disorder that inhibits individuals from speaking in certain social situations despite an ability to speak in more familiar or comfortable settings ( American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). As the year progressed and Jacob went outside more often with his social skills class, he spoke spontaneously with greater frequency, sometimes asking questions and interacting with his peers. Toward the end of the year, Jacob approached a brick wall near the outdoor learning environment that the class was using that day. He noticed a spider spinning a web on the wall. “Look at this!” he called to his friends. Several other children in the group gathered around, and they discussed what the spider was doing and why it was there. Jacob was an active participant in the conversation, engaged and curious.

Since Jacob was a participant in our case study, we were able to observe the ways that he and his autistic peers interacted with their teachers, with each other, and with the environment. Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that consists of several typical behaviors or traits. These include repetitive, stereotyped behaviors and difficulties or impairments with social interaction and communication ( World Health Organization, 1992 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). As it is a spectrum, the needs, abilities, and outcomes of autistic individuals varies greatly. There is limited research on how nature might affect autistic children, especially at school, but there are many anecdotal accounts, which is what inspired our investigation. Higashida (2007) , an autistic Japanese teenager who communicates through a letterboard and computer, shared that nature has the ability to alter his emotions: “Just by looking at nature, I feel as if I’m being swallowed up into it … Nature calms me down when I’m furious and laughs with me when I’m happy” (p. 124). Gordon (2013) wrote about a non-speaking autistic four-year-old child spelling his name for the first time ever while outside using sticks as props. The teacher in Gordon’s article believes that spending time outdoors every day helps children with additional needs accomplish tasks previously believed to be beyond their capabilities. Brewer (2016) highlighted two schools in England that offered opportunities for students with additional education needs to spend time outdoors. According to a teacher at one of the schools, being outside is calming and stress-relieving, especially for autistic students. James (2018) , a British forest school leader, felt so strongly regarding the benefits he saw from taking autistic people into nature that he authored Forest School and Autism: A Practical Guide to encourage others to follow suit. James wrote that there is a lack of research available supporting the use of outdoor spaces with autistic people despite the wealth of anecdotal accounts, including those he details in his book.

Evidence continues to mount that spending time in nature is good for everyone (e.g., Chawla, 2015 ; Williams, 2017 ). While there are numerous studies that demonstrate benefits for typically developing children and adults (e.g., Wells and Evans, 2003 ; Fjørtoft, 2004 ; Swarbrick et al., 2004 ; Morita et al., 2007 ; Berman et al., 2008 ; Abraham et al., 2010 ; Berman et al., 2012 ; Kuo et al., 2018a ), there is limited research on the effects of nature for those with autism. Moreover, using outdoor environments as an accommodation to support autistic students at school is understudied. Therefore, in this case study of two special educators and five autistic students in a social skills group, we addressed the following research questions: What are the challenges and affordances of outdoor learning for autistic children? What are the special educators’ perspectives on outdoor learning with autistic children?

Literature Review

There is growing interest in the use of outdoor environments to benefit children. For instance, the North American Association for Environmental Education (2017) reported that there were 250 nature-based preschools and kindergartens in the United States, a notable increase. Learning outside can serve various educational purposes. The Institute for Outdoor Learning (n.d.) emphasizes “discovery, experimentation, learning about and connecting to the natural world, and engaging in environmental and adventure activities,” which can happen through multi-day trips, residential experiences, and adventure sports. Relatedly, nature-based learning (NBL) is “an educational approach that uses the natural environment as the context for learning” ( Chawla, 2018 , p. xxvii). Forest School (FS) is one example of NBL. The Forest School Association, 2011 , a professional body in the United Kingdom, provides six principles to guide and support FS practitioners. For example, FS takes place in an immersive wooded or natural environment, and learning is child-led. Recent research suggests that FS may facilitate feelings of affinity or ownership over natural spaces, thus encouraging pro-environmental behaviors ( Harris, 2021 ). NBL can, in practice, look many different ways. Access to an immersive wooded or natural environment is not necessary, however. Outdoor learning can occur in urban areas where children explore sidewalks, subways, stores, and parks (e.g., Whitlock, 2020 ).

The effects of engaging with nature are diverse. There are benefits to mental health, including lower stress levels ( Wells and Evans, 2003 ; Morita et al., 2007 ), improved social and emotional wellbeing ( Abraham et al., 2010 ; Berman et al., 2012 ), and feelings of belonging and sense of self ( Swarbrick et al., 2004 ; Cummings and Nash, 2015 ). Interpersonal skills seem to be positively impacted ( Dillon et al., 2005 ), including increased expressions of sympathy toward others and the environment ( Barthel et al., 2018 ). Even nearby nature has notable implications for cognition, intelligence, and development in both educational and residential contexts. Wells (2000) found that, in a study of low-income families with children aged 7–12 years old, moving from a “low naturalness” area to a “high naturalness” area had significant effects for child cognitive function. Similarly, Wells and Evans (2003) , using a four-item naturalness scale, reported that nearby nature may be a buffer for stressful life events for children with a mean age of 9.2 years in rural residential contexts. In a study of adults in Australia, Astell-Burt and Feng (2019) reported that higher amounts of tree canopy (30%) as well as total green space were associated with lower psychological distress and better general health. Bijnens et al. (2020) found that residential green space could have positive impacts on intelligence for children ranging in age from 7 to 15 years old in urban settings.

The benefits of nature for educational purposes have also been documented. Dadvand et al. (2015) , in their study of over 2,500 7 to 10-year-olds in Barcelona, suggested the possibility of improvements in cognitive development associated with surrounding greenness, particularly greenness of schools. Kuo et al., 2018b studied grass and tree cover in a sample of over 318 public schools in Chicago in relation to achievement on state-level assessments. Tree cover was related to academic achievement, particularly for math, while grass cover was not related. Thus, the presence of green spaces in and around schools seems to offer benefits to children. Additionally, Kuo et al., 2018a concluded that classroom engagement from 9 to 10-year-old children increased following lessons that took place in nature, suggesting the potential for what the authors refer to as “refueling in flight” for student focus. This reinforces Kuo et al.'s (2019) sentiment that “it is time to take nature seriously as a resource for learning and development” (p. 6). Considering the existing research, could the same be true for engaging autistic students with nature?

The accommodations and supports each autistic individual requires, if any, are highly variable. A large number of interventions exist to address supposed impairments in autistic populations; these include commonly known interventions such as Applied Behavior Analysis ( Baer et al., 1968 ), TEACHH (Treatment and Education of Autistic and Communications - Handicapped Children; Mesibov et al., 2005 ), and intensive interaction ( Nind and Hewett, 1988 ). The type of intervention or support that an autistic school-age child will receive is dependent on the specifications of that individual's Individualized Education Plan (IEP); the IEP, when used correctly, serves as a roadmap of interventions and supports to attain specific, measurable goals ( Blackwell and Rossetti, 2014 ). Difficulties with social interactions, for example, may prompt the use of an intervention like a social skills group. Group social skills training involves the teaching and practice of social skills among peers. This is the context of our case study. The worthwhileness of such an intervention for targeting the social skills of autistic children remains unclear, with some evidence of effectiveness ( Hotton and Coles, 2016 ) and other authors concluding that the intervention has little impact ( Bellini et al., 2007 ); despite this, the teaching and practicing of social skills in a group setting remains a common practice in special education ( DeRosier et al., 2011 ).

School experiences can be difficult for autistic children, leading to increased mental health issues and additional support needs. Due to the differences or difficulties in social communication common in autistic people, interactions with peers can be complex and challenging, causing stress and anxiety. Autistic children are also more likely to be bullied at school because of their behavioral differences ( Rowley et al., 2012 ). In fact, autistic children and teenagers are more likely to experience bullying and victimization than typically developing peers and peers with intellectual disability. Additionally, autistic children may experience gaps in academic achievement as well due to social impairments and other difficulties not related to intellect or ability ( Estes et al., 2011 ). It is not surprising, then, that mental health issues are more prevalent among the autistic population than the general population, with some researchers reporting estimates of 20% of the autistic population experience co-occurring anxiety disorders ( Lai et al., 2019 ). Confounded with the usual difficulties of childhood and adolescence, school can be a tumultuous time for autistic students.

One potential avenue of support for autistic individuals that is underutilized and understudied is the use of outdoor environments. While there is extensive research showing that time spent in nature offers benefits for wellbeing, particularly mental health, and even cognition and intelligence in typically developing populations or those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), there is far less research on what nature might offer autistic people, especially children. According to Blakesley et al. (2013) , gardening projects, summer camps, field visits, and animal therapy have shown to have positive effects for autistic children; however, more research on the potential of outdoor learning for autistic children at school is needed.

The research that does exist is promising. Bradley and Male (2017) interviewed four autistic children, ages 6–8 years old, who participated in FS as well as their parents. Despite the small sample size, several benefits were identified from the interviews; these included friends/friendship development, challenges and risk taking, learning outcomes, and experiencing success. Zachor et al. (2016) utilized quantitative methods to study the impact of an outdoor adventure program on the autistic symptomatology of 51 autistic children between the ages of 3–7 years, with findings indicating a reduction of symptomatology after participation in the outdoor group when compared to a control group. Additionally, Li et al. (2019) interviewed caregivers of autistic children in China, who ranged in age from 4 to 17 years old, and “identified multiple sensory-motor, emotional, and social benefits of nature for children with autism” (p. 78). The findings from these three studies demonstrate that learning outdoors may need to be considered an accommodation and intervention for autistic children. Further evidence, especially in a school context, would bolster the research base and potentially lead to nature-based accommodations for autistic children.

Theoretical Framework

This study is framed by the theory of stress recovery put forward by Ulrich et al. (1991) . Stress recovery theory (SRT) suggests that following a bout of stress, individuals who are exposed to natural settings are able to reduce that stress more quickly than those who were not exposed to natural settings, demonstrated even at a parasympathetic level. The authors noted that the idea of stress recovery occurring in natural settings is not a new one; it has been documented throughout history, including in evolutionary theories. Stress reduction has also been observed in a study using nature sounds rather than visual natural scenes ( Alvarsson et al., 2010 ). Decades of research show that natural settings contribute to decreased stress and associated mental health issues ( Wells and Evans, 2003 ; Morita et al., 2007 ; Abraham et al., 2010 ; Berman et al., 2012 ).

SRT has also been applied in a sample of 18 11-year-olds, some of whom were considered to have “bad” behavior. Roe and Aspinall (2011) measured mood and reflection on personal development before and after a typical indoor lesson and a FS session. The authors reported that greater positive behavioral change occurred after time in the forest environment, suggesting that the restorative potential of nature may have been at play. Additionally, SRT underpinned work conducted by Shao et al. (2020) in which 26 elementary-aged children performed first an electronic gardening task followed by a real-life horticultural activity. Various physiological measurements (e.g., heart rate variability and skin conductance) indicated that the children experienced positive impacts from the real-life horticultural activity, including a decrease in sympathetic nervous activity. Thus, SRT has been applied to work with a range of ages, including younger children.

As previously noted, autistic individuals have a more difficult school experience. Additionally, the levels of mental health issues among the autistic population is much higher than that of typically developing peers ( Lai et al., 2019 ). It is likely that those challenging and sometimes traumatic school experiences are among several factors contributing to increased mental health issues among school-age autistic children. Due to its significant and continued impact upon wellbeing and various outcomes, the school experience and associated mental health issues should be of focus for teachers, caregivers, counselors, interventionists, and other practitioners who engage with this population. Stress recovery offered by educational activities occurring in nature could be beneficial, then, by mitigating the stressful experiences of attending school or interacting socially with others.

Research Methods

As a case study, this is a preliminary investigation of a phenomenon over which we had little control ( Yin, 2017 ). According to Miles et al. (2019) , a case is “a phenomenon of some sort occurring in a bounded context” (p. 44). Thus, our case is a social skills group consisting of two special educators and five autistic students who used both indoor and outdoor environments at an elementary school in the southeastern United States. Furthermore, this is an exploratory case study given that it was not intended to test a particular hypothesis ( Yin, 2017 ). As noted by Hancock and Algozzine (2011) , exploratory case studies serve as a prelude for more expansive investigations that might seek to confirm a hypothesis or work with a concept in a more in-depth manner. Given the small sample size, our findings are not generalizable.

The case study was carried out at a public K-5 elementary school with approximately 600 students, an estimated 47% of whom are eligible for free or reduced price lunch. The school, which we will call Belington Elementary (pseudonym), has a special education department consisting of two teachers, both of whom participated in this study. They provide both push-in and pull-out support for students with IEPs, and they also co-facilitated a 30-min social skills group with five autistic students every day.

The purpose of this social skills group was to offer guidance and practice for communicating and interacting with peers through a variety of lessons. Sometimes the teachers provided direct instruction regarding specific concepts. For example, the teachers might read a book in which one of the characters demonstrates emotion regulation, or they might facilitate a matching activity that required students to align particular situations, as stated by the teacher, to the coordinating emotions that the individual in the fictional situation was likely feeling. Sometimes the teachers prompted the students to engage with each other through games and free play. For example, the teachers invited the students to build well-known international monuments using materials found outside in small groups, which required cooperation and collaboration. Social skills interventions are commonly used for autistic children, particularly those in mainstream environments, as they teach the social interaction behaviors that would be considered “typical” in society. The behaviors may include maintaining eye contact, reducing atypical speech patterns, and expressing interest in what other conversation partners are saying ( White et al., 2010 ). Social skills training programs have been reported to be effective in targeting perceived “deficits” or differences in social interaction (e.g., Kamps et al., 1992 ; Webb et al., 2004 ; Cappadocia and Weiss, 2011 ).

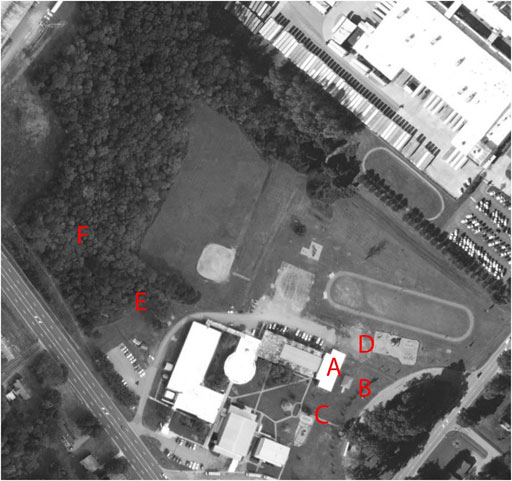

There were four outdoor environments generally used by the teachers for this case study (see Figure 1 ). First was a small pavilion situated very close to the school building. Next to the pavilion was a small garden, but it was overgrown and not actively used by anyone at the school. The second area was referred to as “the outdoor classroom” and was located in a more open area next to the school. The outdoor classroom consisted of several picnic tables under a large covering. Both the pavilion and the outdoor classroom were located just outside the door from the special education classroom, which both teachers shared. The third area was the playground, blacktop, and field located at the back of the school. Finally, there was a nature trail that led to a small clearing in a wooded area. There were wooden benches that formed a circle in the clearing. Accessing the nature trail required a slightly longer walk out of the building, across the parking lot, and over a small patch of grass. For the purposes of our research, we considered the pavilion, outdoor classroom, and playground/blacktop/field areas to be sites for outdoor learning; activities that took place in the nature trail and clearing in the wooded area were considered NBL due to the more immersive setting.

FIGURE 1 . Belington elementary campus. A = Indoor Classroom, B = Outdoor Classroom, C = Pavilion, D = Playground and Blacktop Area, E = Nature Trail, F = Forest Classroom

Participants

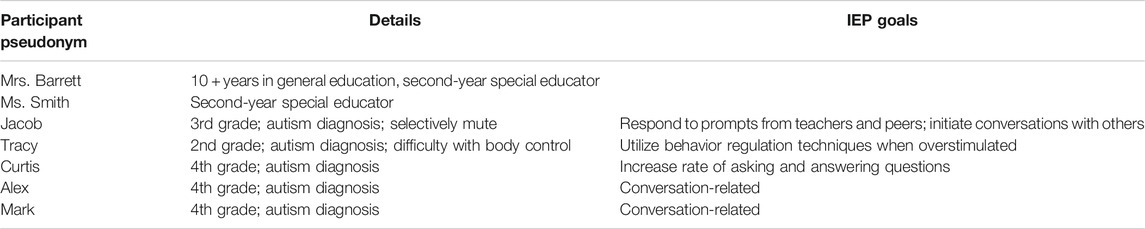

Participants included two special educators and five autistic students. The teachers, Mrs. Barrett and Ms. Smith (pseudonyms), were both in the early stages of their careers in special education. While Ms. Smith graduated from university two years prior, Mrs. Barrett worked for over 10 years in several other education and childcare contexts before seeking a special education qualification. Both teachers had minimal experience taking autistic children outside the classroom and no formal training or experience with outdoor learning. The social skills group was composed of five students from 2nd, 3rd, and 4th grades. All of them identified as male and white, had autism diagnoses, and spoke English as their first language. Basic descriptive information regarding the participants can be found in Table 1 .

TABLE 1 . Participant information.

Data Collection

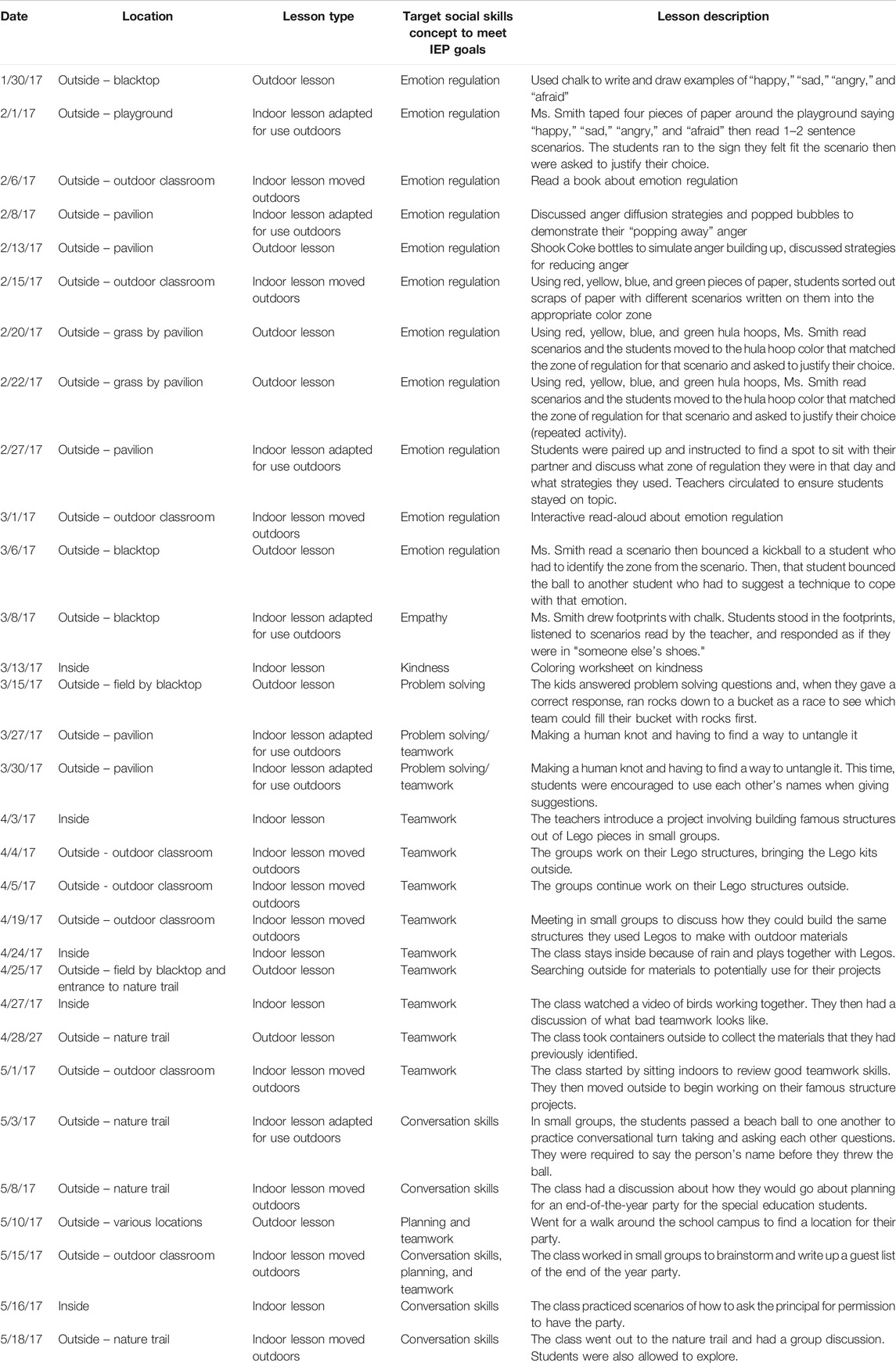

A total of 31 visits were carried out, with 26 observations taking place outside and 5 taking place indoors. One visit was completed at the end of January while 7–8 visits were completed per month from February to May. Visits were typically on Mondays and Wednesdays, though seven of the visits were on other days of the week due to events at the elementary school, which meant the class was unable to meet, or to observe the children indoors. The 30-minute social skills classes met in the afternoon each day during the last lesson block of the day. At the start of the study, the teachers agreed among themselves that they would take the children outside on Mondays and Wednesdays. This plan sometimes changed due to weather or a change in lesson plans. Thus, the decision regarding which days to go outside was predetermined, but the teachers had the autonomy to make adjustments day-to-day. We did not observe the students during other subjects.

Field notes were handwritten when at the school and later typed on a shared document. We elaborated on the field notes on the shared document, which resulted in longer narratives. We also tracked the frequency of certain behaviors exhibited by three of the students (Curtis, Jacob, and Tracy; pseudonyms) in our field notes. The target behaviors were related to the IEP goals for each student; the purpose of focusing on IEP goals was to observe if an outdoor environment facilitated any progress or development in regards to those particular goals. Behavior frequency was noted throughout the entire class period, with tally marks indicating the presence of the target behavior. Further details denoting the content of the behaviors were recorded as well. For example, if Curtis asked a question, we would write down what he asked. The decision to track behaviors for only three of the five students was made due to the other two children’s IEP goals. That is, their goals were generally conversation-related but difficult to track using frequencies. Thus, we focused on tracking behaviors of three students with goals that could be more easily quantified.

Finally, we conducted semi-structured interviews with both teachers at the beginning, middle, and end of the data collection period. Interviews lasted 30–45 min and were carried out in person at the school. The first two interviews were with each teacher separately (i.e., two interviews for each) and the final interview was with both teachers together in an effort to provide a space for reflection and discussion between them. In the first interview, questions focused on their previous experiences working with children (both indoors and outdoors), their own relationship with nature, their feelings about incorporating outdoor learning, and their initial impressions or observations of their first few sessions outdoors. The second interview included questions regarding outdoor lesson planning inspiration, how the teachers felt the group was managing with outdoor lessons, how they themselves were impacted by taking their lessons outside, any difficulties they encountered, and how they were beginning to use outdoor learning with their other groups throughout the day. The final interview focused on reflections from both teachers regarding the challenges they faced throughout the experience and what they felt they did to be successful in outdoor environments. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

We followed Miles et al.'s (2019) guidance regarding qualitative data analysis. To start, we conducted two phases of coding on the interviews and field notes. Coding served to categorize like pieces of data. The first cycle of coding utilized several of the many types of coding, including descriptive, in vivo , and emotions coding. The purpose of the first cycle of coding was to summarize two of the available data sources. The second cycle of coding served to identify patterns in those codes. Codes were then grouped together into categories or themes.

Next, we completed a round of jottings. Jottings documented our thinking as we analyzed the data. These brief notes were written directly into the interview and field note documents to ensure continuity between the data that prompted the thought and the thought itself. Following the use of jottings, analytic memoing then served to “synthesize (descriptive summaries of data) into higher level analytic meanings” ( Miles et al., 2019 , p. 97). Beyond just noting thoughts about the data, analytic memos extend and connect various data with theory and researcher perception.

To formalize and organize our thoughts and findings, we produced assertions and propositions based on all sources of data. According to Miles et al. (2019) , assertions are declarative statements while propositions are conditional statements that serve to predict. These statements allowed us to look at the findings comprehensively and better determine the entire picture of what occurred throughout the study, based upon the available data. To summarize and conclude the process, we carried out a within-case analysis to describe what occurred within the single case of focus in our study.

Limitations

Case studies, particularly those that are exploratory and utilizing within-case analysis, are not generalizable as they focus in depth on one particular case to better understand some aspect of that case. More time observing the participants and conducting the study over a longer period of time would have given us a more robust set of data. Finally, the special educators in this case study were not experts in outdoor learning and had very limited experience taking students outside. Therefore, the challenges and affordances we found may be unique to this context.

When Mrs. Barrett and Ms. Smith agreed to participate in this case study, we had to rely on their willingness, creativity, and resilience to regularly use outdoor environments with their social skills group. Our first research question pertained to the effects of being outside on autistic students, but the second research question about special educators’ perceptions of outdoor learning was perhaps more significant. Mrs. Barrett and Ms. Smith decided what days they would go outside, where on the school campus they might go, what concepts and topics to integrate into their lessons, whether they were adequately meeting IEP goals, and how to respond to autistic students’ needs during transitions and disruptions to their routines. They were the conduits for the entire case study. If for any reason they were not comfortable using outdoor environments, we would not have been able to observe their students.

Neither of the special educators had significant prior experience or training with NBL. During our first interview, Ms. Smith said that she had not used the outdoor environments at her school very often, “just taking them out a few times last year.” She continued, “I would take them out to the outdoor classroom... sometimes on a nice sunny day” but confessed she did not have “a lot of experience incorporating, like, outdoor instruction or environmental education.” When we asked what inspired her to use the outdoor environments a few times, she said,

I thought that was really cool, and I kind of wanted to explore them too, um, just 'cause I knew we had a trail. I knew we had the outdoor classroom there for a reason, and I enjoyed it outside, especially like when the weather was nicer, and I figured it was a fun break for my students, too.

Even without much prior experience or training, both Ms. Smith and Mrs. Barrett found going outside to be appealing enough to participate in this study, and their comfort levels increased the more they used the outdoor environments. Mrs. Barrett noted during her second interview, “We were kind of hesitant before (about) going outside,” but then quickly followed with, “Now that we (are more) experienced... it's just like, calmer. It's peaceful. I just want to stay out there all day.” Both special educators found that outdoor environments offered more than just a fun break for students.

Before we began observing the social skills group, Ms. Smith and Mrs. Barrett shared with us the general IEP goals for their five autistic students. In an email, they highlighted the specific skills they would be working on during the study:

• Engaging in appropriate conversation with others (listening to others, asking relevant questions, using a “social filter”)

• Using “appropriate verbalizations” to express feelings and needs rather than shutting down or using aggressive/physical behaviors

• Identifying others’ perspectives and feelings

• Identifying the problem in a social situation and creating a solution to meet both party’s needs (problem-solving skills)

• Completing non-preferred tasks

• Asking for a break when frustrated

• Demonstrating verbal control in different social situations

They also stressed that there was not a set curriculum that they were required to follow, which allowed them the flexibility of creating their own lessons in ways that would meet their students’ needs and IEP goals. In fact, they were used to developing their own curriculum. “Last year we didn’t have any type of curriculum (provided),” they wrote in the email, “so we pulled from a lot of online resources.” From the beginning, Mrs. Barrett and Ms. Smith were both cautiously optimistic about regularly using outdoor environments with their autistic students. Their lack of experience and training was not insurmountable. Rather, they displayed a growth mindset throughout the study. This was especially apparent in the lessons they developed.

The first outdoor lesson we observed took place in the blacktop area just outside of their classroom (location D on Figure 1 ). The main objective was to support students’ identification of emotion states, so Ms. Smith wrote “happy,” “sad,” “angry,” and “afraid” on four distinct spaces on the blacktop in chalk. The students were then tasked with drawing pictures or writing words with chalk that they associated with the emotion words. The spaces for drawing were approximately five feet away from each other; the children worked in pairs, rotating to the various spaces as the lesson progressed. Throughout the lesson, students were observed laughing and smiling. Some children found nearby rocks on the ground and threw them toward the field while they were taking breaks from drawing. At the end of the activity, everyone sat on the ground in a circle to summarize what they learned. The students were largely engaged in the activity, though some noted that sitting on the hard ground hurt their hand or that the cracks in the asphalt got in the way of their drawing. Despite the colder weather on this day, the only comments about feeling cold came from adults present.

During the second outdoor lesson we observed, the children were noticeably different in their expressions of emotion and interactions with one another compared to their behavior at the start of the class indoors. When observation began at the start of class, before the group had moved outside, the children were being kept on the carpet because the teachers felt they were not following instructions to be quiet and still. Once outside, the activity, which involved running to various parts of the playground to select an emotion word that described the scenario being read aloud (e.g., happy, sad, angry), prompted smiles, laughter, happy screaming, and talking among the students. This was true for Jacob as well, which caused Ms. Smith to comment that she’d never before seen Jacob speak to peers unprompted during an activity.

Several days later, they took a book about emotion regulation outside to the picnic tables to read as a group. While Ms. Smith read aloud, many of the students moved their bodies, tapping on the tables and alternating between standing and sitting. At one point during the lesson, Jacob was moving around rocks and items he found on the ground. Ms. Smith asked a question specifically addressed to him in what appeared to be an attempt to re-engage him in the story. During the following outdoor lesson, the group reviewed the book. Then, to enhance their understanding of the book, Mrs. Barrett and Ms. Smith showed the students a container of bubbles, pulled out the plastic wand, and blew a few into the air. The bubbles were meant to indicate feelings of anger that eventually build up until they pop. The students provided answers to the question, “What makes you angry?” and then were to chase a bubble and “pop” it. Jacob and Tracy in particular seemed to enjoy the opportunity to run after and pop bubbles, as they laughed and smiled throughout this portion of the activity. Mark seemed eager to help Ms. Smith with blowing the bubbles.

During the next outdoor lesson, the concept was advanced further through the use of a liter bottle of soda. The lesson began with a discussion of what they learned about being angry or frustrated from the bubble popping activity. During this review, Tracy and Jacob were moving around, displaying stimming behaviors, and standing up. The teachers shook the bottle to indicate the process of getting angry. The bottle was then opened, and some of its contents spilled out, much to the delight of the children. This prompted a conversation about what strategies could have been used to prevent the spill. The students suggested taking a break while shaking the bottle to allow the fizzing to calm down, which they demonstrated with another bottle of soda. They waited a few minutes after shaking the bottle, and the students discussed whether this was a long enough break to prevent another explosion. During this portion of the lesson, Tracy was corrected by the teachers for not paying attention. This was then related to strategies that they could use to defuse anger. These strategies were demonstrated through the use of skits; the students were put into two groups and tasked with acting out a situation where someone was upset and had to employ a strategy to diffuse their anger. The children largely participated in the skits, though Tracy commented that he was cold and spent some time zipping and unzipping his jacket. Additionally, Jacob was not taking part in this activity, as he was slightly away from the group, touching one of the gazebo’s columns. This was not acknowledged by the teacher.

Continuing with the theme of emotion regulation, another activity on a particularly warm and sunny day included four hula hoops with colors coordinating to the Zones of Regulation, an emotional control system created by Leah Kuypers. The four colors help to categorize different emotions, with blue indicating low alertness, green indicating calm states, yellow indicating elevated emotions, and red indicating extremely elevated emotions. One of the teachers read a scenario, and the children responded by moving to the hula hoop that corresponded to the regulation zone they felt was represented by the scenario. For instance, one scenario was, “Tommy was walking to his table in the cafeteria when he dropped his tray of food. All of his food went on the ground. What zone do you think Tommy was in when this happened?” At first, all of the children moved together, seeming to make the same decisions. Eventually, students broke off and made their own choices about what zone matched best. Throughout the activity, Alex appeared to be dancing as he participated. When students did choose a hula hoop that no one else went to, the teachers asked them to justify their choice, prompting a discussion. For instance, toward the end of the activity, Jacob broke off from the group and went to a different hoop than his peers. The teachers then asked him to explain why he made that choice.

After several months of incorporating outdoor environments into their instruction, the teachers planned a series of lessons to develop teamwork skills. During an indoor class lesson, the students began to work on a small group project. The groups were tasked with building well-known structures out of Legos (e.g., Statue of Liberty, Sphinx, Great Wall of China). The next day, the class took their Lego projects outside to work at the outdoor classroom under the pavilion. Several classes later, the teachers told the students that they would be repeating the same process of building famous structures in small groups; this time, though, the students would be utilizing whatever natural materials they could find outside. Over the course of several outdoor lessons, the students, in their groups, brainstormed what types of materials they would need, where they could get those materials outside, and how they would build the structures. One day was spent on the nature trail collecting materials in a bucket to take back inside. Then, several lessons, both indoor and outdoor, were spent creating their structures. The outdoor lessons to prepare for making a famous structure out of natural materials were interspersed with indoor lessons teaching, reviewing, and discussing what teamwork looks like. That is, concepts were taught inside that were then immediately incorporated into outdoor activities, creating an indoor-outdoor transfer of skills and knowledge.

The aforementioned are only a small sample of the lessons planned and executed by Ms. Smith and Mrs. Barrett for their social skills group with autistic students. Table 2 presents details about all of the lessons that were observed during the study.

TABLE 2 . Descriptions of lessons.

Our analysis of the data revealed the challenges experienced by the special educators and their students, the adaptations the teachers made in response to the challenges, and the affordances for everyone in the case study.

Not surprisingly, taking autistic children into new learning environments has its challenges. To begin, there were several reasons why the teachers, who taught at a school with several well-developed outdoor spaces, had never utilized these locations before. The main barrier was timing; the teachers had only 30 min with their social skills group and were hesitant to use some of that limited time to travel to and from the outdoor environments. Once the teachers tried taking their group out, they realized that “it didn’t take as long to get out there as I thought it would.” Importantly, they used that transition time effectively, as we explain below, incorporating it into their lesson so that travel time was not “wasted” time.

Once the group started going outside more regularly, the teachers found that an additional barrier was the weather; more specifically, a lack of appropriate clothing and footwear for adverse weather conditions sometimes stopped the class from going outside. On one day, the teachers changed the plans to go outside “because it was raining and cold, and we didn't want anybody getting sick.” Another day, the class decided to stay inside because one of the students had new shoes on and didn’t want to get them muddy on the nature trail.

Over the course of the study, the teachers also came to realize that not all of the outdoor spaces available to them were equal. That is, the class had several options, including a pavilion close to the school that had a view of the front parking lot, where buses and parents would line up at the end of the school day; the playground, blacktop, and field behind the school that had a view of a road; and the nature trail and outdoor classroom that was secluded from any views of the road or the school. Ms. Smith quickly found that “they’re able to focus more when we're in areas further away from the road.” Both teachers agreed that the students were less “distracted” when they were in the nature trail and forest classroom, leading them to prefer taking the students there.

It seems that this preference was shared by the students as well; during one lesson, Ms. Smith told the students they would be going to the pavilion, and several students groaned and expressed that they felt that space was boring because “it’s just land.” When outside at the pavilion or on the field that had views of the road, there were several instances of children becoming noticeably “distracted” when large trucks passed by, often commenting on what they saw. Additionally, several of the children experienced anxiety related to knowing what time it was and having sufficient time to prepare for going home. Thus, when the class was at the outdoor pavilion and the students could see parents and buses arriving for pickup, this anxiety increased and became disruptive to the lesson.

Despite the clear barriers that existed, the teachers persisted in incorporating outdoor learning into their social skills class. This persistence necessitated a willingness by the teachers to adapt accordingly.

Adaptations

On a larger scale, both teachers underwent a transition in their approach to teaching this particular social skills group. As mentioned previously, neither teacher had experience taking children, particularly autistic children, outside for educational purposes. Throughout the study, both became more confident and comfortable with taking autistic children, and children with other additional needs, into outdoor environments. They became so comfortable, in fact, that they began taking children from their other groups, including reading and math support groups, outside. This was not an expectation of the study; rather, the teachers noticed the effects on themselves and their students and were compelled to try it on their own.

In a more literal sense, the importance of transitions to the success of the group’s outdoor lessons was quickly apparent. An initial apprehension existed with both teachers regarding the amount of time that would be spent walking to the outdoor environments in use for that lesson. Because of this, the teachers often opted for closer locations when going outside, such as the playground, grass field behind the school, or pavilion that was right next to the building; the students often complained when they were told this was their destination for the day, however. Additionally, there were downsides to these more easily accessible outdoor environments such as proximity to roads and parking lots and the presence of other classes. This challenged the teachers to find a way to access a more secluded outdoor location and deliver a meaningful lesson within the 30-minute time frame of the class session.

To do this, Ms. Smith found that transition time could be effectively harnessed so that the five-minute walk to the more secluded outdoor environment on the nature trail became a feasible option for the class. During several sessions, Ms. Smith used the time spent walking back into the building to have individual “check-outs” with the students. Describing her thought process for doing this, Ms. Smith said, “That’s why I was like, let’s just do individual check-outs as we walk back instead, where I just talk to them one-on-one, because they’re not listening to each other as a group … I just checked in with a couple as we walked to ask them, ‘Hey, do you think you met your goal today, and how did you do that?’ I talked to at least three or four of them.” On trips from the building out to the nature trail, the teachers sometimes explained rules, procedures, and expectations for the day, told the class what the planned activity was, or asked individual students what emotion regulation zone they felt they were in at that time. On other days, transition time was used to play “I Spy” to encourage students to pay attention to their surroundings. With their newfound realization of the impact that effective transitions can have, both teachers felt that “trying to plan for those transitions” during lesson planning was particularly crucial to increasing the chances for success.

While we offered the teachers support with brainstorming ideas and developing lesson plans, they did not ask for this help and were insistent on using their own ideas. To start, the teachers often opted to take the lessons they would use indoors and simply move them to an outdoor environment. For instance, they did this several times with read-aloud books and post-reading discussions. Early in the study, Ms. Smith mentioned that she was “very comfortable taking indoor activities outside. But I don’t necessarily feel like I’m great at using what’s outside for the lesson.” After observing this, we found that lessons could be categorized in four ways: indoor lessons delivered inside, indoor lessons that are simply moved into an outdoor setting, indoor lessons that are adapted to utilize some element of the outdoor setting, and lessons designed for use only outdoors.

An added difficulty was the topic that this particular group needed to cover: social skills. Ms. Smith found this more difficult as “social skills was something like, I don't know if I was, if I would say I was necessarily, like, really taught how to teach necessarily.” In an effort to utilize the outdoors for social skills lessons more effectively, the teachers found that it was easiest to search for one of those elements -- outdoor learning or social skills -- and then adapt the idea they’ve found to include the other element. Thus, they avoided the frustration of trying to find ideas for “social skills lessons outdoors,” which may not readily exist online.

To source ideas for their outdoor lessons, the teachers utilized online searches and platforms like Pinterest as well as asking their colleagues for input, and they had success with these methods. Lesson planning required a learning curve, though, as Ms. Smith noted that she had to realize that “it’s okay to, like, go back to something that's worked because it's familiar and it's good … good for them, too. Because I think some, at the beginning, I was just feeling pressured to like come up with something new every time, too.” Additionally, the teachers had to remember that going outside meant they were able to utilize an entirely new set of materials. Ms. Smith found that her “normal frame of mind is worksheets. Videos … maybe a game inside. But now, it's like I need to think about a different space, different materials and what not.” With this, Ms. Smith demonstrated how she adapted her approach to lesson planning during the study.

Adaptations were evident throughout the five months of the study. For instance, the teachers learned that their class responded best when new concepts were introduced indoors and follow-up activities were conducted outside, rather than trying to teach new concepts in the outdoor environment. The teachers believed that this was the case because “when you’re outside, you don’t want to just be sitting and listening. They’re ready to move and be active.” Allowing for movement and physical activity -- taking advantage of having more space outdoors -- was another key to success for the class as the teachers focused on “trying to incorporate more movement, so we've done a lot of games.” Additionally, understanding that lessons don’t have to be complicated to be impactful meant that outdoor lessons felt more approachable for the teachers. Ms. Smith stated that “coming up with your own ideas is a little bit easier now. Like, just thinking of the spaces that we have and … just it's easier to think about. I was like, ‘Well, we can take a walk outside,’ like even just something as simple as taking a walk outside to see all the different places.”

The teachers also expressed that flexibility, both in carrying out lesson plans and in expectations, was key when taking their autistic students outside. For instance, on one day that was intended to be an indoor lesson, the class took a vote to decide where they would prefer to work; four of the students voted to work outside, so the class moved locations and simply took the indoor lesson into the outdoor classroom. This happened quite frequently, as Ms. Smith noted that the class was spending more time outside than what was required from the study because “the kids have been asking to.” During another lesson, Mrs. Barrett realized that she had forgotten one of the key materials, a small whiteboard, inside. She adapted the lesson to account for this, having the children act out the scenarios she was going to draw instead, resulting in a successful lesson.

While the class certainly discussed and adhered to rules and procedures for being outside in order to keep all of the students as safe as possible, the expectations that students were held to evolved as the class spent more time outside. Certain behaviors were discouraged in any setting, such as interrupting teachers or classmates by speaking out of turn. Others, however, were allowed in the outdoor space as the teachers noticed that they adapted their own attitudes toward what constituted acceptable behavior while outdoors. Mrs. Barrett admitted that, when taking the class outside, she was “more flexible with [them]... I don’t expect them to sit still.” She also shared that while she still expected students to listen to her as she teaches, those specific listening behaviors that she is looking out for are also different outside, noting that “I can tell. I can say, ‘Okay. So who … ’ And they say it right back. I know they're listening.” Additionally, observations of the class and teachers indoors showed that sitting still and showing body language that was indicative of focus on the teacher were expectations; children who deviated from these expectations were given reminders of “proper” behavior. When outdoors, however, bodily movement became more accepted, with Mrs. Bartlett sharing, “One chose to sit on the boardwalk and the other three sat on the bench. Well, one started off on the bench and he went off, under the bench. Like, okay. Whatever. As long as you're listening, I'm good.”

Despite the adaptations that the teachers made toward more accepting and flexible behavioral expectations when outside, styles of instruction that would align more closely with NBL or FS, the lessons remained fairly “traditional” in that they were teacher-centered and lesson-centered. Each lesson focused on a particular skill that was addressed; these skills aligned with expectations of what a social skills group should cover and included, during the time of the study, constructs such as emotion regulation, teamwork, problem solving, and conversational turn-taking. A further shift toward an embrace of NBL or FS would result in lessons being more child-centered, child-led, and inquiry-based. These adaptations were not observed during the study.

Affordances

During our observations, we tracked the frequency of certain behaviors exhibited by three of the students, Jacob, Tracy, and Curtis; the target behaviors were selected based upon the students’ IEP goals. Jacob’s goal involved “being able to communicate basic wants and needs and … asking and answering questions.” Tracy’s IEP goal was to utilize self-regulation skills to identify and remove himself from situations that made him over-stimulated, and Curtis’ goal was to ask questions to elicit more information, rather than staying silent, which can then lead to frustration. We wanted to see if being outside might help these students meet the goals in their IEPs.

In tracking Curtis’ goal, we found that his question asking increased more indoors compared to outdoors. Those indoor questions, however, pertained to going outside. For instance, during one session, Curtis asked about a specific material that was being brought outside and if he could help carry it. In another, he asked if he could wear his sunglasses outside. While outdoors, Curtis noticed a helicopter leaf on the ground. After he asked what it was, Ms. Smith helped him to pick it up and throw it in the air to watch how it floated to the ground. The number of times Curtis asked questions certainly increased overall, and it appeared that his interest or enjoyment in going outside prompted those questions.

During the study, Tracy did not utilize any self-regulation techniques. We did not observe him reach a point of being over-stimulated during any of the outdoor or indoor sessions that we observed. This suggests that, despite some fears from the teachers, the outdoor environments did not overwhelm or worsen any feelings for Tracy. To the contrary, we noticed that Tracy enjoyed being outside and looked forward to learning in the outdoor environments. In fact, several situations occurred while outdoors that reasonably could have led to conflict or feeling overwhelmed but did not. For instance, during the lesson where the class read a book about diffusing anger, one of his peers seemed to become annoyed with Tracy’s movements (stomping on the ground) and yelled, “Stop!” In response, Tracy stopped what he was doing and further conflict was avoided. In several other instances, Tracy was directed to pay attention or stop a certain behavior; in each case, Tracy effectively followed the teacher or peer’s directions and re-engaged with the activity. This was in contrast to the indoor lessons, where his behavior was observed to be more chaotic and unsettled. During one indoor lesson, Tracy interrupted the lesson by whispering, “Tornado!” unprompted. He then pretended to play the drums on his legs and moved his body and mouth throughout the rest of instruction. In another indoor lesson that required the students to sit on the carpet and watch a video, Tracy repeatedly spoke aloud during the video.

Perhaps most strikingly, Jacob’s goal of increasing his utterances as well as his responses to questions was clearly and certainly addressed while outside. Jacob spoke and responded to prompts more frequently while outside compared to inside; it also seemed that teachers and peers prompted Jacob to speak more frequently while outside as well. Reflecting on this, Ms. Smith said, “[Jacob] speaks up more. He speaks up more to his classmates, I would say, outside. Like, I think, ‘cause … he feels like there’s more space between him and the teacher … but he does initiate more conversation to his peers outside than he does inside.” Mrs. Barrett attributed this to the outdoor environment, noting, “[Ms. Smith] told me that he talked, had a conversation with another student in front of her, and he asked a question, point blank, to her … Very unusual. That’s where we see him, like, even after school, when they're outside playing, that's when we see him really interacting, is outside. That's when he … That’s his forte, I guess.” This was evident from the first outdoor lesson, when Ms. Smith noted that Jacob was speaking to his peers as she’d never observed before, through to one of the last sessions that we observed when Jacob and his peers found a spider on its web. When asked if he preferred the classroom or being outdoors, Jacob replied, “Outdoors.”

Separate from the frequency tracking of specific IEP goals, the group also experienced additional affordances from spending time outside. Ms. Smith observed “a higher energy level outside, just in more of an eagerness to participate because it's almost like it’s a surprise, what we're gonna, like, what are we gonna do now? And the kids really do look forward to it every time they come in.” The unpredictability of the use of outdoor environments excited and interested the students.

Both teachers repeatedly mentioned that all of their students were more focused while outside and exhibited clearer signs of listening during activities. Additionally, several students who were more prone to shouting out or interrupting other speakers inside were noticeably calmer and shouted out far less while outside. This was particularly true for Mark; according to Ms. Smith, “(Mark) doesn't call out as much outside. He listens more. I don't know why, but he does. I don't know if it's the environment or he knows we're doing something new so he has to pay attention more.” One of Mark’s daily behavioral goals was to reduce instances of blurting out in class; thus, these observations were particularly significant to the teachers.

Finally, the students seemed to benefit from the fresh air, the ability to more freely move around, and the ability to fidget or move when necessary while still listening without disrupting their peers’ learning. Additionally, while instances of the students struggling with behavior outside were very infrequent, Mrs. Barrett did note that the class “did have one incident out there where (a student) shut down, but after the … incident, like, he refused to move. So, we just calmly had everyone come back in because it was at the end. I let him sit there … He got up. Because usually before in the classroom, he would throw chairs, desks, things.” Thus, students potentially had more space to safely work through the process of regulating their emotions when outside. Most importantly, perhaps, in assuaging any fears that teachers may have about taking their autistic students into a new environment is Ms. Smith’s view that “no one’s (behavior has) gotten worse outside.”

The students were not the only participants who experienced clear positive effects from spending time outside. Both teachers repeatedly noted ways that they benefited from the experience as well. The teachers felt that the outdoor environments required them to be more creative in lesson planning. While this may have been challenging at times, they also noted that it made them “more thoughtful about the space we use and how we use it.” Additionally, the teachers seemed to harness the feelings of being challenged by their mission to use the outdoor environments in a productive way, sharing that while it was sometimes intimidating, they found the experience exciting as well. The other main impact that the teachers experienced was increasing feelings of peacefulness and calm while taking the students outside. Ms. Smith said that she doesn’t “feel quite as drained after being outside. I think it’s more refreshing because it's a break from the usual.

Nature can serve as an accommodation to support autistic students in meeting IEP goals, particularly due to the positive impact time outside has on stress reduction ( Ulrich et al., 1991 ). Our observations suggest that the outdoor environments did not hinder progress in meeting IEP goals and, in some cases, may have facilitated opportunities to work toward those goals due to lower stress levels.

Jacob, for instance, did not speak unprompted in the social skills class for the first half of the year when the class was inside, likely due to selective mutism. Selective mutism is reported as being connected to stressful life experiences, including those occurring at school ( Muris and Ollendick, 2015 ), though some autistic individuals with selective mutism are reported as not speaking due to a lack of interest in the social context rather than shyness or anxiety ( Steffenburg et al., 2018 ). It is possible that this was a factor for Jacob as well. During the first trip outside and in many subsequent sessions, Jacob participated verbally. There could be a number of reasons that Jacob felt more able to speak while outside; these include having physical distance from the teachers, feeling more relaxed and enjoying class more, or the different style of activities used in some instances outside (e.g., incorporating more physical movement). Additionally, the stress reduction that occurs in nature might have allowed Jacob to feel comfortable enough to speak. Whatever the reason, it was evident from tracking Jacob’s utterances, both prompted and unprompted, that being outside led to an increase in utterances, moving him closer to that specific IEP goal.

In the case of Tracy, the outdoor environments did not cause him to feel overstimulated to the point of having difficulty regulating his feelings or behavior. While we are not able to conclude whether this was from being in an outdoor space or if another alternative education space that was indoors would have had a similar effect on him, it is possible that the stress reduction from being outdoors minimized feelings of overstimulation. Regardless, the impact of the outdoor environments on Tracy was not a negative one. Both Jacob and Tracy’s suspected experiences of lower stress levels outdoors are supported by prior research (e.g., Wells and Evans, 2003 ; Chawla, 2015 ).

Finally, the outdoors seemed to provide a topic of conversation for Curtis, as he asked several questions regarding the details of his class going outside. In the case of all three students, being outside did not hinder their progress toward addressing their IEP goals; rather, our data suggest that outdoor environments moved them closer to reaching those goals. Given the well documented negative effects that poorly designed indoor classrooms can have on autistic children ( McAllister and Maguire, 2012 ), accessing an educational space that does not have those same detrimental impacts could have additional beneficial effects and should be considered as a relatively accessible support or accommodation. Despite the aforementioned benefits, it is important to avoid romanticizing the positive impacts of time outdoors for autistic children. It is unreasonable to expect that all people, including all autistic children, will enjoy being outdoors all of the time or respond positively; in some cases, time in or near nature may increase anxiety ( Larson et al., 2018 ).

While this began as a study focused on how outdoor environments might affect autistic students, the picture that emerged following five months of data collection placed the teachers’ experiences front and center as well. The two special educators demonstrated a growth mindset; they began the study with no outdoor learning experience, confronted the barriers that they came across throughout the process, and appreciated the benefits that outdoor learning offered to themselves and their students. This growth mindset was likely supported by the impacts to teachers that we did not expect. There are many legitimate reasons why teachers may be hesitant to take their students outside; these include time constraints, safety concerns, lack of confidence, or rigidity in developing lessons to adhere to standards ( Rickinson et al., 2004 ; Dyment, 2005 ). Several of these barriers were factors for the teachers in the study, particularly the lack of confidence and feelings of having insufficient time. Despite the presence of these challenges, Ms. Smith and Mrs. Barrett persisted and continued to take their students outside. Thus began what seemed to be a feedback loop: the more the teachers took their students outside, the more the students looked forward and expected to go outside. Furthermore, as the teachers gained more experience taking their social skills group outside, their confidence increased to the point that, unprompted, they began taking their other classes outside as well.

Additionally, teachers are undoubtedly under a tremendous amount of stress, which can lead to burnout and negative impacts to wellbeing ( Richards et al., 2018 ). While we initially expected Ulrich et al.'s (1991) SRT to be a factor influencing how autistic students responded in the outdoor environment due to reported stressful school experiences, it is possible that the teachers equally benefited from stress reduction while outside, evidenced by continued mention of feelings of calm, enjoying the peace of the outdoors, and feeling less drained. It would seem that in the midst of a chaotic school day, spending time outside offered a reprieve for the teachers that outweighed the difficulties of identifying and planning lessons to execute outside. Feelings of lowered stress and increased relaxation are among the most commonly noted positive effects of exposure to nature for adults ( Maller et al., 2006 ; Morita et al., 2007 ; Cole and Hall, 2010 ).

In particular, Mrs. Barrett seemed to undergo a stark transformation. When approached about the research, we received a more reluctant acceptance from Mrs. Barrett; it seemed that Ms. Smith naturally took the lead, likely due to a higher comfort level with the topic or more motivation to tackle the opportunity. Whatever the reason, it is due to this initial hesitance that Mrs. Barrett’s experience taking her students outside is more striking. When interviewing her at the end of the study, she reported having opted to take her other special education classes outdoors as well, citing the positive feelings that she got from the experience as a driving factor. She made at least three references to feeling peaceful and calm while outdoors in her second interview. Mrs. Barrett also seemed to evolve in her expectations of her students while outside, mentioning that as long as she knew her students were listening, she did not mind them moving around or choosing to stand or lay down while she taught outside. This contrasted with her teaching style inside, which was far more structured and emphasized traditional listening cues such as sitting upright, being quiet, and maintaining eye contact.

Future Research

Despite our initial focus on the development of the students, the teachers in our study, Ms. Smith and Mrs. Barrett, became crucially important to the overall case. The evolution and impacts that they experienced suggest that future research should explore the wellbeing effects for teachers who take their students outside as well as the implications this may have for job satisfaction, teacher retention, and reducing burnout.

In our observations of a social skills class consisting of five autistic students and their two special education teachers who incorporated outdoor learning into their day for five months, we saw a range of affordances available to teachers and students alike and ample evidence of their enjoying these affordances. Harnessing such benefits in an educational context requires teachers who are willing and capable of supporting students in engaging with the outdoors. Ms. Smith and Mrs. Barrett, neither of whom had any previous experience or training with taking autistic children outside to learn, were able to adapt their existing knowledge and skills to support their students in learning in the new environment. Additionally, there was no evidence of students experiencing negative outcomes or feeling worse while outside. Coupled with the progress that students such as Jacob showed during the outdoor lessons, this suggests that nature should be considered as an option to meet the needs of autistic children during the school day. This case study serves to demonstrate that, even for teachers with no prior experience taking children into nature, outdoor learning is possible and beneficial to everyone involved.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Elon University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

SF and SM contributed to conception, design, and recruitment for the study. SF collected data. Both SF and SM contributed to analysis. SF wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and both SF and SM revised and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jessica Wery and Maddie Craft for their assistance on this study.

1 Following Kenny et al.’s (2016) study of preferred terminology in the autism community, we are using identity-first language throughout.

Abraham, A., Sommerhalder, K., and Abel, T. (2010). Landscape and Well-Being: A Scoping Study on the Health-Promoting Impact of Outdoor Environments. Int. J. Public Health 55 (1), 59–69. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-0069-z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alvarsson, J. J., Wiens, S., and Nilsson, M. E. (2010). Stress Recovery during Exposure to Nature Sound and Environmental Noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7 (3), 1036–1046. doi:10.3390/ijerph7031036

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing .

Astell-Burt, T., and Feng, X. (2019). Association of Urban Green Space with Mental Health and General Health Among Adults in Australia. JAMA Netw. Open 2 (7), e198209. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8209

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., and Risley, T. R. (1968). Some Current Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis1. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1, 91–97. doi:10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91

Barthel, S., Belton, S., Raymond, C. M., and Giusti, M. (2018). Fostering Children’s Connection to Nature through Authentic Situations: The Case of Saving Salamanders at School. Front. Psychol. 9, 928. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00928

Bellini, S., Peters, J. K., Benner, L., and Hopf, A. (2007). A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Social Skills Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Remedial Spec. Edu. 28 (3), 153–162. doi:10.1177/07419325070280030401

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., and Kaplan, S. (2008). The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature. Psychol. Sci. 19 (12), 1207–1212.

Berman, M. G., Kross, E., Krpan, K. M., Askren, M. K., Burson, A., Deldin, P. J., et al. (2012). Interacting with Nature Improves Cognition and Affect for Individuals with Depression. J. Affective Disord. 140 (3), 300–305. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.012

Bijnens, E. M., Derom, C., Thiery, E., Weyers, S., and Nawrot, T. S. (2020). Residential Green Space and Child Intelligence and Behavior across Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas in Belgium: A Longitudinal Birth Cohort Study of Twins. Plos Med. 17 (8), e1003213. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003213