- Open access

- Published: 27 March 2023

The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

- Malak Bleibel 1 ,

- Ali El Cheikh 2 ,

- Najwane Said Sadier 1 , 3 &

- Linda Abou-Abbas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9185-3831 1 , 4

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy volume 15 , Article number: 65 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

41k Accesses

14 Citations

51 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of music interventions as a non-pharmacological therapy to improve cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients has gained popularity in recent years, but the evidence for their effectiveness remains inconsistent.

To summarize the evidence of the effect of music therapy (alone or in combination with pharmacological therapies) on cognitive functions in AD patients compared to those without the intervention.

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, Cochrane library, and HINARI for papers published from 1 January 2012 to 25 June 2022. All randomized controlled trials that compared music therapy with standard care or other non-musical intervention and evaluation of cognitive functions are included. Cognitive outcomes included: global cognition, memory, language, speed of information processing, verbal fluency, and attention. Quality assessment and narrative synthesis of the studies were performed.

A total of 8 studies out of 144 met the inclusion criteria (689 participants, mean age range 60.47–87.1). Of the total studies, 4 were conducted in Europe (2 in France, 2 in Spain), 3 in Asia (2 in China, 1 in Japan), and 1 in the USA. Quality assessment of the retrieved studies revealed that 6 out of 8 studies were of high quality. The results showed that compared to different control groups, there is an improvement in cognitive functions after music therapy application. A greater effect was shown when patients are involved in the music making when using active music intervention (AMI).

The results of this review highlight the potential benefits of music therapy as a complementary treatment option for individuals with AD and the importance of continued investigation in this field. More research is needed to fully understand the effects of music therapy, to determine the optimal intervention strategy, and to assess the long-term effects of music therapy on cognitive functions.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, incurable neurological illness that is the most common cause of dementia, affecting an estimated 5% of men and 6% of women over the age of 60 worldwide [ 1 ]. The prevalence of AD increases exponentially with age, with 1% of those aged 60 to 64 years old and 24% to 33% of those aged 85 years or older affected [ 2 ]. As the global population ages, it is anticipated that the number of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease will increase.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy, depression, and agitation, are commonly observed in individuals with AD, in addition to the more well-known cognitive symptoms such as memory loss, visuospatial problems, and difficulties with executive functions [ 3 , 4 ]. These symptoms can cause a significant burden to patients, caregivers, and society as a whole [ 5 ]. While pharmacological therapies have been used to manage these symptoms, they have not always been effective in achieving long-term clinical efficacy [ 6 ]. As a result, non-pharmacological interventions have gained increasing attention as a complementary treatment option for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD. Such therapies include cognitive training and music therapy which have been used for decades to improve symptoms of dementia [ 7 ].

Music Therapy is the use of music to address the physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals [ 8 ]. The American Music Therapy Association describes music therapy as the use of music interventions in a clinical and evidence-based manner to achieve specific goals, which are tailored to the individual, by a professional who is credentialed and has completed an approved music therapy program [ 8 ]. Music therapy incorporates a crucial aspect of the interaction between the client and therapist through an evidence-based model [ 9 ]. It can include both active techniques, such as improvisation, singing, clapping, or dancing, and receptive techniques, where the client listens to music with the intention of identifying its emotional content [ 9 ]. In music listening approaches, the therapist creates a personalized playlist for the client, which can either be an individualized program or chosen by the therapist [ 9 , 10 ]. Generalized music interventions use music without a therapist present, with the goal of enhancing the patient’s well-being, and can include both active and music listening protocols. Music listening is used to stimulate memories, verbalization, or encourage relaxation [ 9 ].

For many years, music therapy has been used to help manage symptoms of dementia [ 9 , 11 ]. Music therapy can improve mood, cognitive functions, memory, and provide a sense of connection and socialization for patients who may be isolated [ 12 , 13 ]. Studies have found that musical training may help mitigate the effects of age-related cognitive impairments, and the capacity of persons to remember music makes it a good stimulus that engages AD patients [ 7 , 14 , 15 ]. After listening to music, AD patients showed improvement in categorical word fluency [ 16 ], autobiographical memory [ 17 , 18 ], and the memory of the lyrics [ 15 ]. Additionally, it can provide an opportunity for caregivers to participate in therapy sessions, which can improve the overall caregiving experience by giving them the opportunity for self-expression allowing them to depict their thoughts and emotions [ 19 ].

The specific mechanisms by which music therapy is beneficial are not fully understood. In 2003, research indicates that music may activate neural networks that remain intact in individuals with AD [ 20 ]. A recent study by Jacobsen et al. [ 21 ] used 7 T functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine the brain’s response to music and identify regions involved in encoding long-term musical memory. When these regions were evaluated for Alzheimer’s biomarkers, such as amyloid accumulation, hypometabolism, and cortical atrophy, the results showed that, although amyloid disposition was not significantly lower in the AD group compared to the control group, there was a substantial reduction in cortical atrophy and glucose metabolism disruption in AD patients [ 21 ]. These findings suggest that musical memory regions are largely spared and well-preserved in AD, which could help explain why music therapy is so effective in retrieving verbal and musical memories in individuals with the disease [ 21 ].

One experimental paradigm used to study the effects of music therapy in AD is the use of live music performances, in which a music therapist plays live music for individuals with the disease in a group setting [ 22 ]. Another paradigm is the use of individualized music, in which a music therapist creates a playlist of personalized music for an individual with the disease to listen to at home [ 23 ]. Both paradigms have been shown to be effective in improving mood and reducing agitation in individuals with AD [ 22 , 23 ].

The advantages of music therapy for AD patients include its non-invasive nature and lack of side effects, its ability to address multiple symptoms at once, and its cost-effectiveness and ease of implementation [ 9 , 18 , 24 , 25 ]. However, there are also some limitations to its application. Music therapy may not be suitable for patients with severe dementia [ 26 ] as their cognitive and physical abilities may be too impaired to fully participate in therapy sessions. Additionally, it requires trained therapists [ 8 , 9 ], who may not be easily accessible in some areas. In this review, we aimed to summarize the evidence of the effect of music therapy (alone or in combination with pharmacological therapies) on cognitive functions in AD patients compared to those without the intervention.

This systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA 2009) guidelines [ 27 ]. The protocol of this study was registered in PROSPERO. A statement of ethics was not required.

We used the PICO framework (population, intervention, comparator, and outcome) as follows:

P: Alzheimer patients

I: Music therapy (alone or in combination with pharmacological therapies)

C: Alzheimer patients with and without the intervention

O: Cognitive functions

Search strategy and databases

A systematic literature search of PubMed, Cochrane, and HINARI was performed for studies published in peer-reviewed journals from 1 January 2012 up to 25 June 2022. The databases were searched using the keywords of “Alzheimer’s Disease,” “AD,” “music therapy,” “music intervention,” “cognitive functions,” and “cognition.” Keywords were combined using the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND.”

Study selection and eligibility criteria

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published between 2012 and 2022 in the English language and providing quantitative measures of the association between AD and music therapy and its effect on cognitive functions were included in our review. Studies that assess the effect of music therapy on patients with a probable diagnosis of AD or studies where the music therapy was combined with another non-pharmacological therapy are excluded.

Data extraction

Search and identification of eligibility according to inclusion criteria and extraction of data were performed by the two reviewers MB and AC. For each paper, detailed information was collected on: study information (author’s name, publication year, and location), sample characteristics (sample size, age, and gender), study design, intervention details (description, duration) the control group, and the cognitive outcome measures.

Methodological quality assessment

A methodological quality assessment of all included studies was performed by two independent reviewers (MB and AC) using the Jadad scale for RCTs [ 28 ]. Although not used as a criterion for study inclusion or exclusion. Jadad scale is developed to assess randomized controlled trials on the bases of 3 essential items: (1) randomization, 1 point if randomization is mentioned 1 additional point if the method of randomization is appropriate and deduct 1 point if the method of randomization is inappropriate,(2) blinding 1 point if blinding is mentioned, 1 additional point if the method of blinding is appropriate, deduct 1 point if the method of blinding is inappropriate; (3) an account of all patients, the fate of all patients in the trial is known. If there are no data, the reason is stated. It is commonly considered that a study is of “high quality” if it scores 3 points or more.

Study selection

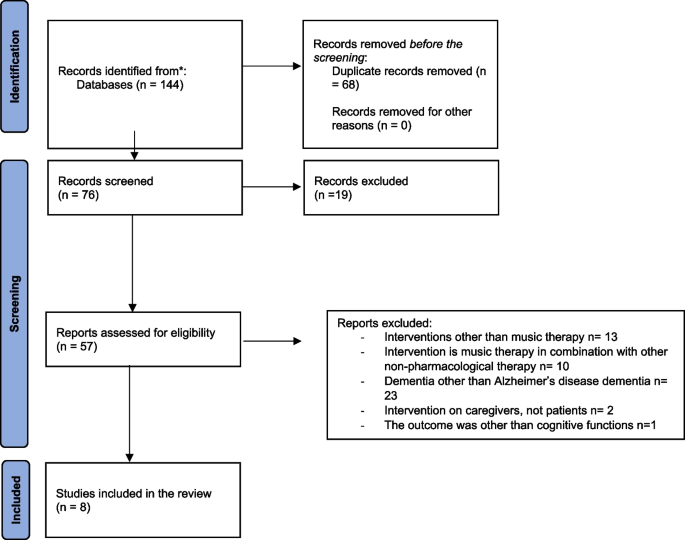

The flowchart of the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1 . The literature search identified a total of 144 records. After the exclusion of duplicate records and non-relevant abstracts, 57 studies were retained. After reviewing the full text, 49 studies were excluded according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the end, a total of 8 full-text studies were included in the qualitative synthesis.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection procedure

Study characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1 . The final sample was composed of 8 RCTs, 4 studies were conducted in Europe (2 in France, 2 in Spain), 3 studies in Asia (2 in China, 1 in Japan), and one in the USA. All these studies were published in the English language in peer-reviewed journals. Included trials showed a total of 689 participants (300 females, 43.54%). Sample sizes ranged from 39 [ 29 ] to 298 [ 30 ]. Mean ages ranged from 60.47 [ 31 ] to 87.1 [ 26 ]. Participants’ stages of AD dementia varied from mild to severe. Mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [ 32 ] at baseline is assessed in 7 trials out of 8 and varied from 4.65 [ 29 ] to 25.07 [ 33 ].

Intervention characteristics

Music therapy approach.

Music therapy methods were heterogeneous across the included studies. In one study, the active music therapy approach used was singing with the played songs [ 33 ]. Two other studies used the receptive (passive) music therapy approach which consists in listening to music and songs played on a CD player [ 31 , 35 ]. The remaining five studies were based on a combination of both active and receptive music approaches [ 26 , 29 , 30 , 34 , 36 ].

Comparators

In four studies, music therapy intervention was compared to standard care [ 29 , 30 , 34 , 35 , 36 ], while in the four remaining studies, different interventions other than music therapy were used as comparators such as: watching nature videos [ 36 ], painting [ 33 ], cooking [ 26 ], and practicing meditation [ 31 ].

Application of the intervention

Only three trials were conducted by a music therapist [ 29 , 34 , 36 ], 1 trial was conducted by a professional choir conductor [ 33 ], 1 by musicians [ 30 ] and the 3 remaining trials were conducted with facilitators with no musical expertise [ 26 , 31 , 35 ].

Types of applied music

Seven trials out of 8 were based on individualized songs (chosen according to patient’s preferences or songs that are used to evoke positive emotions in them) [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. The remaining trial was based on familiar songs chosen without considering the patient’s preferences [ 26 ].

Outcome characteristics

The included studies assessed different outcomes, but we focused on domains directly related to outcome inclusion criteria: global cognition, memory, language, speed of information processing, verbal fluency, and attention. All cognitive outcomes and measurement tools used across studies are listed in Table 1 .

Risk of bias

The quality of trials was assessed by Jadad scales [ 28 ]. Studies with scores ≥ 3 were classified as high-quality studies and those of ≤ 2 were classified as “low-quality” studies. [ 26 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 ] studies were considered high-quality studies while [ 34 , 35 ] studies were considered of low-quality. Blinding of participants was not possible due to the nature of the intervention considered in this review. Randomization was mentioned in all studies except one study [ 34 ]. Results of the quality assessment of all studies using the Jadad scales are summarized in Table 2 .

Results of individual studies

Sakamoto et al. [ 29 ] studied the effect of music intervention (active and passive) on patients with severe dementia. Results showed that there is a short-term improvement in emotional state assessed by the facial scale which is a tool commonly used by psychologists and healthcare professionals to assess and code facial expressions, both positive and negative, to determine a patient’s emotional state [ 37 , 38 ]. In addition to eliciting positive emotions, music therapy has been shown to have long-term benefits in reducing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia assessed by the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (BEHAVE-AD) Rating Scale, a well-established instrument to assess and evaluate behavioral symptoms in AD patients, as well as to evaluate treatment outcomes and identify potentially remediable symptoms [ 39 ].

The study by Narme et al. [ 26 ] was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of music and cooking interventions in improving the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral well-being of AD and mixed dementia patients. The study lasted 4 weeks and involved 48 patients, who received two 1-h sessions of either music or cooking interventions per week. Both interventions showed positive results, such as improved emotional state and reduced the severity of behavioral disorders, as well as reduced caregiver distress. However, there was no improvement in the cognitive status of the patients. Although the study did not find any specific benefits of music interventions, it suggests that these non-pharmacological treatments can improve the quality of life for patients with moderate to severe dementia and help to ease caregiver stress [ 26 ].

The study by Gómez Gallego and Gómez García [ 34 ] showed a significant increase in MMSE scores, especially in the domains of orientation, language and memory [ 34 ]. Subsequent study from the same author aiming to compare the benefits from active music therapy versus receptive music therapy or usual care on 90 AD patients showed impressive results of active music intervention improving cognitive deficits and behavioral symptoms [ 36 ]. Other supportive data revealed an increase of MMSE and MoCA scores over the study duration in the intervention group, in comparison to the control group [ 35 ].

The study by Pongan et al. [ 33 ] examined the effects of singing versus painting on 50 AD patients over a period of 12 weeks. Results showed that both therapies elicited benefits in reducing depression, anxiety, and pain. The only advantage that the singing group had over the painting group is the stabilization of verbal memory (assessed using FCRT) over time [ 33 ].

Lyu et al. [ 30 ] study aimed to investigate the effects of music therapy on cognitive functions and mental well-being in AD patients. The study utilized the World Health Organization University of California-Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test (WHO-UCLA AVLT) to assess the short-term and long-term memory of the participants. Subjects were tested on their ability to recall 15 verbal words immediately and after a delay of 30 min. The results showed that music therapy was more effective in improving verbal fluency and alleviating psychiatric symptoms and caregiver distress than lyric reading in AD patients. The stratified analysis revealed that music therapy improved memory and language ability in mild AD patients and reduced psychiatric symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor activity) and caregiver distress in moderate or severe AD patients. However, no significant effect was found on daily activities in any group of patients [ 30 ].

Innes et al. [ 31 ] study consisted of testing music listening therapy over a period of 12 weeks. Cognitive functions were assessed through various measures, including memory (using the Memory Functioning Questionnaire MFQ), executive function (using the Trail Making Test (TMT) Parts A and B), and psychomotor speed, attention, and working memory (using the 90-s Wechsler Digit-Symbol Substitution Test). The scores assessed at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months after therapy showed an improvement in measures of memory function, psychological status, and cognitive performance including executive functions, working memory, processing speed, and attention [ 31 ].

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia, pose a major challenge to global health and will continue to increase in impact with the aging population. AD is a widespread form of dementia affecting a large number of elderly individuals globally and may contribute to 60–70% of cases [ 40 ]. Despite efforts to find effective treatments through pharmacological means, the results have been disappointing in recent decades. As a result, non-pharmacological therapies have gained more attention as a way to improve cognitive, behavioral, social, and emotional functions in AD patients.

Music therapy has been shown to induce plastic changes in some brain networks [ 41 ], facilitate brain recovery processes, modulate emotions, and promote social communication [ 42 ], making it a promising rehabilitation approach. Thus, the present systematic review aimed to systematically synthesize the impact of music therapy on cognitive functions in AD patients. Out of the eight studies reviewed, totaling 689 subjects, seven studies found a significant and positive effect of music therapy on enhancing cognitive functions in individuals with AD. However, one study by Narme et al. [ 26 ] did not find evidence of the efficacy of music therapy on cognitive functions [ 26 ]. This result may be due to the use of music that was chosen by the therapist, rather than being based on the patient’s preferences, and the use of cooking as a control group rather than a standard group to test the efficacy of the intervention. Furthermore, Narme et al. [ 26 ] suggested that a larger sample size would be beneficial in conducting parametric analysis, which could provide more robust results [ 26 ]. These findings highlight the potential benefits of music therapy as a non-pharmacological intervention for AD patients.

Six out of eight studies revealed that patients who underwent Active Music Intervention (AMI) had better outcomes compared to those who underwent Receptive Music Intervention (RMI) [ 29 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. On the other hand, the findings of the studies by Innes et al. [ 31 ] and Wang et al. [ 35 ] that used only the RMI approach, showed a positive impact on cognitive functions in AD patients [ 31 , 35 ].

In the study by Innes et al. [ 31 ], both the meditation and music listening groups showed significant improvements in cognitive functions, without a significant difference between the two groups. In the study by Wang et al. [ 35 ], music therapy was found to be an effective adjuvant to support pharmacological interventions in AD, leading to significant improvements in the MMSE and MoCA scores. It is worth noting that AMI and RMI differ in terms of the level of patient involvement and the objectives of the therapy. AMI involves the direct participation of patients in musical activities such as singing, playing an instrument, or moving to the beat, whereas RMI consists of passive listening to music. From a functional and physiological perspective, AMI may have a greater impact on cognitive and emotional processes due to the increased level of engagement and interaction with the music [ 36 ]. AMI has been shown to activate brain regions involved in auditory processing, motor control, and emotional regulation, leading to improved cognitive functions and reduced agitation and anxiety [ 41 ]. On the other hand, RMI may have a more relaxing effect, as it can induce changes in heart rate and breathing, reducing stress levels and improving sleep quality [ 42 ]. Based on our systematic review, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the optimal music types (classic music, familiar songs, individualized songs…) for music therapy in patients with AD. This is due to the heterogeneity of the studies included in our review, including differences in the types of music used and the methods of exposure. Therefore, it is not possible to determine with certainty which type of music is most effective for improving cognitive functions in AD patients. Further research is needed to establish the optimal music types and optimal duration of music therapy in this population. Our findings also revealed that individualized music playlists, consisting of songs chosen based on the patient’s preferences, showed improvement in cognitive functions, particularly in memory. A study by [ 31 ] used relaxing music in the intervention group, chosen according to patients’ preferences. The music listening CD to be heard by patients in this study contained selections from Bach, Beethoven, Debussy, Mozart, Pachelbel, and Vivaldi, which resulted in an improvement in cognitive functions. This is consistent with the [ 43 ] study which showed that listening to classical music, specifically selections from Mozart, could result in a temporary improvement in certain cognitive tasks such as abstract/spatial reasoning tests. While the “Mozart Effect” has been linked more to the acute arousal brought on by the pleasure of listening to music, rather than a direct impact on cognitive ability [ 44 ], both studies highlight the potential for listening to classical music to have a positive impact on cognitive functions.

The improvement in orientation, language, and memory domains in individuals with AD, as reported in the studies by [ 34 , 36 ], can be attributed to several factors such as the use of an individualized playlist or the presence of a music therapist to perform the sessions. The study by [ 30 ] suggests that music intervention has a positive effect on verbal fluency, memory, and language in individuals with AD. The rhythmic and repetitive elements of music regulate brain function, and musical activities such as singing and playing instruments can activate neural networks involved in memory and language processing.

Further beneficial effects other than improved cognitive behaviors, memory, language, and orientation, the study by [ 29 ] showed a positive impact on the emotional state of the patients. This is consistent with the idea that several cognitive processes such as perception, attention, learning, memory, reasoning, and problem-solving, are all influenced by emotions [ 45 ]. However, the positive effects observed in the emotional state of the patients disappeared 3 weeks after the intervention period. The effects of the intervention lasted after the follow-up for a period that varied between studies [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 ], from 1 month [ 33 ] to 6 months [ 30 , 31 ]. Further research is needed to determine the most effective and optimal duration for music therapy interventions.

Our review has some limitations including differences in participant characteristics (participant age/severity of illness/cognitive ability…), outcome measures, and intervention methods, that may have influenced the results. Additionally, the music therapy interventions used in the studies differed, with activities ranging from singing to playing instruments. These factors, combined with the small number of studies included in the review, limit the power of our findings. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the interventions and outcome measures used in the studies makes it difficult to perform a meta-analysis and combine the data in a meaningful way. The varying methods of music selection and exposure also pose challenges in synthesizing the results.

The findings of this review suggest that music therapy could have a positive impact on cognitive functions in patients with AD. This supports the growing body of evidence that targets music therapy as a promising cognitive rehabilitating process aiming to improve cognitive functions in individuals with AD dementia like memory, executive functions, or attention. Improvements in these cognitive functions can, in turn, enhance the quality of life of both the patients and their caregivers. However, more research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind these effects and to determine the optimal approach to music therapy for this population, including the time frame for follow-up evaluations. Nevertheless, the results of this review highlight the potential benefits of music therapy as a treatment option for individuals with AD and the importance of continued investigation in this field, including long-term follow-up assessments to determine the sustained impact of music therapy on cognitive functions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- Alzheimer’s disease

Active music therapy

Behavior Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease

Digit Symbol Substitution Test

Frontal assessment battery

Free and Cued Recall Test

Memory Functioning Questionnaire

Mini-Mental State Examination

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

Positron emission tomography

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Randomized controlled trials

Receptive music therapy

Severe impairment battery

Trail Making Test

United States of America

World Health Organization University of California-Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning test

World Health Organisation (WHO). World Health Organisation. Summary: World report on disability 2011 (6099570705). 2011. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575 .

Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, Miller DS, Smith GS, Bell J, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013;9(5):602–8.

Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Burns A. The burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;3(7):31–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1461145700001905 .

Berg-Weger M, Stewart DB. Non-pharmacologic interventions for persons with dementia. Missouri Med. 2017;114(2):116.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, Rantanen P. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: randomized controlled study. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):634–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt100 .

American Music Therapy Association AMTA member sourcebook. The Association (1998). retrieved from: https://www.musictherapy.org/ .

Raglio A, Oasi O. Music and health: what interventions for what results? Front Psychol. 2015;6:230. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00230 .

Tang H-YJ, Vezeau T. The use of music intervention in healthcare research: a narrative review of the literature. J Nurs Res. 2010;18(3):174–90.

McDermott O, Crellin N, Ridder HM, Orrell M. Music therapy in dementia: a narrative synthesis systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(8):781–94.

Koelsch S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(3):170–80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Raglio A, Attardo L, Gontero G, Rollino S, Groppo E, Granieri E. Effects of music and music therapy on mood in neurological patients. World J Psych. 2015;5(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.68 .

Article Google Scholar

Schellenberg EG, Hallam S. Music listening and cognitive abilities in 10-and 11-year-olds: The blur effect. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1060(1):202–9.

Simmons-Stern NR, Budson AE, Ally BA. Music as a memory enhancer in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(10):3164–7.

Thompson RG, Moulin C, Hayre S, Jones R. Music enhances category fluency in healthy older adults and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Exp Aging Res. 2005;31(1):91–9.

Irish M, Cunningham CJ, Walsh JB, Coakley D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Coen RF. Investigating the enhancing effect of music on autobiographical memory in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(1):108–20.

Peck KJ, Girard TA, Russo FA, Fiocco AJ. Music and memory in Alzheimer’s disease and the potential underlying mechanisms. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(4):949–59.

Popa LC, Manea MC, Velcea D, Şalapa I, Manea M, & Ciobanu AM. Impact of Alzheimer's dementia on caregivers and quality improvement through art and music therapy. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060698

Platel H, Baron J-C, Desgranges B, Bernard F, Eustache F. Semantic and episodic memory of music are subserved by distinct neural networks. Neuroimage. 2003;20(1):244–56.

Jacobsen J-H, Stelzer J, Fritz TH, Chételat G, La Joie R, Turner R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138(8):2438–50.

Cox E, Nowak M, Buettner P. Managing agitated behaviour in people with Alzheimer’s disease: the role of live music. Br J Occup Ther. 2011;74(11):517–24.

Park H, Pringle Specht JK. Effect of individualized music on agitation in individuals with dementia who live at home. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(8):47–55.

Leggieri M, Thaut MH, Fornazzari L, Schweizer TA, Barfett J, Munoz DG, Fischer CE. Music Intervention Approaches for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of the Literature. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00132 .

Van der Steen JT, Smaling HJ, Van der Wouden JC, Bruinsma MS, Scholten RJ, Vink AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2018. (7).

Narme P, Clément S, Ehrlé N, Schiaratura L, Vachez S, Courtaigne B, et al. Efficacy of musical interventions in dementia: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014;38(2):359–69.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):1–11.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

Sakamoto M, Ando H, Tsutou A. Comparing the effects of different individualized music interventions for elderly individuals with severe dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(5):775–84.

Lyu J, Zhang J, Mu H, Li W, Champ M, Xiong Q, et al. The effects of music therapy on cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;64(4):1347–58.

Innes KE, Selfe TK, Brundage K, Montgomery C, Wen S, Kandati S, et al. Effects of meditation and music-listening on blood biomarkers of cellular aging and Alzheimer’s disease in adults with subjective cognitive decline: An exploratory randomized clinical trial. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;66(3):947–70.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Pongan E, Tillmann B, Leveque Y, Trombert B, Getenet JC, Auguste N, et al. Can musical or painting interventions improve chronic pain, mood, quality of life, and cognition in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;60(2):663–77.

Gómez Gallego M, Gómez García J. Music therapy and Alzheimer’s disease: Cognitive, psychological, and behavioural effects. Neurologia. 2017;32(5):300–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2015.12.003 .

Wang Z, Li Z, Xie J, Wang T, Yu C, An N. Music therapy improves cognitive function and behavior in patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(5):4808–14.

Google Scholar

Gómez-Gallego M, Gómez-Gallego JC, Gallego-Mellado M, García-García J. Comparative efficacy of active group music intervention versus group music listening in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8067.

McKinley S, Coote K, Stein-Parbury J. Development and testing of a faces scale for the assessment of anxiety in critically ill patients. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(1):73–9.

Pautex S, Michon A, Guedira M, Emond H, Lous PL, Samaras D, et al. Pain in severe dementia: Self-assessment or observational scales? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1040–5.

Monteiro IM, Boksay I, Auer SR, Torossian C, Ferris SH, Reisberg B. Addition of a frequency-weighted score to the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale: the BEHAVE-AD-FW: methodology and reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(Suppl 1):5s–24s. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00524-1 .

World Health Organisation (WHO). World Health Organisation. Dementia. 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia .

Schlaug G. Part VI Introduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1169(1):372–3.

Thompson W, Schlaug G. Music can heal the brain. Scientific American: MIND. 2015.

Rauscher FH, Shaw GL, Ky CN. Music and spatial task performance. Nature. 1993;365(6447):611–611.

Thompson WF, Schellenberg EG, Husain G. Arousal, mood, and the Mozart effect. Psychol Sci. 2001;12(3):248–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00345 .

Tyng CM, Amin HU, Saad MNM, Malik AS. The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Medical Sciences, Neuroscience Research Centre, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

Malak Bleibel, Najwane Said Sadier & Linda Abou-Abbas

Pierre and Marie Curie Campus, Sorbonne University, Paris, France

Ali El Cheikh

College of Health Sciences, Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Najwane Said Sadier

INSPECT-LB (Institut National de Santé Publique Epidémiologie Clinique Et Toxicologie-Liban), Beirut, Lebanon

Linda Abou-Abbas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: MB and LAA, Data collection, extraction, and quality assessment MB and AC, supervision, LAA, writing—original draft preparation, MB; Critical revision of the article: LAA and NSS; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Linda Abou-Abbas .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Neuroscience Research Committee.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bleibel, M., El Cheikh, A., Sadier, N.S. et al. The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alz Res Therapy 15 , 65 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01214-9

Download citation

Received : 26 August 2022

Accepted : 15 March 2023

Published : 27 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01214-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive functions

- Music therapy

- Music intervention

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy

ISSN: 1758-9193

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Managing...

Music as a person-centred intervention for dementia

Rapid response to:

Managing neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

Dear Editor

In their timely review of person-centred interventions for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia, Watt and colleagues do not foreground an intervention of high relevance to many people living with dementia: music.

Evidence from meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials [1,2] suggests that music-based therapeutic interventions in dementia can reduce depressive symptoms and ameliorate behavioural disturbance and may also reduce anxiety and improve emotional well-being and quality of life. Benefits may be further enhanced by ‘personalised playlists’ holding particular resonance for the individual living with dementia [3], potentially even in the later stages of the illness when opportunities for intervention are often limited. Music is a source of meaningful occupation in dementia [4] – a cornerstone of wellbeing in the delivery of person-centred care. By facilitating communication, it may also reduce the frustration and helplessness that contribute significantly to challenging behaviours.

As a therapeutic intervention, music is innocuous, accessible, flexible and relatively easy to implement. Over and above its beneficial effects on standard neuropsychiatric symptom indices of dementia, music is a lifelong source of pleasure and resilience for a great many people, and may help to maintain social connectedness in ways that are difficult to quantify. Music is a unique source of solace against the loneliness and despair that too often attend dementia: a lesson that the Covid-19 pandemic has poignantly affirmed.

Laura M Bolton, Music Therapist, Older People Mental Health, NHS Lothian Arts Therapies Service, United Kingdom [email protected]

Jessica Jiang, Research Psychologist, Dementia Research Centre, University College London, London, United Kingdom [email protected]

Jason D Warren, Professor of Neurology, Dementia Research Centre, University College London, London, United Kingdom [email protected]

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the authors’ own and do not represent the NHS or other affiliated organisations.

Acknowledgments. Our research in music and dementia is supported by the Alzheimer’s Society, the Royal National Institute for Deaf People, a Frontotemporal Dementia Research Studentship in Memory of David Blechner (funded through The National Brain Appeal) and UCL Music Futures.

1. Van der Steen JT, Smaling HJ, van der Wouden JC, Bruinsma MS, Scholten RJ, Vink AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 7: CD003477. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003477.pub4

2. Dorris JL, Neely S, Terhorst L, VonVille HM, Rodakowski J. Effects of music participation for mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021; 69: 2659-2667. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17208.

3. Lineweaver TT, Bergeson TR, Ladd K, Johnson H, Braid D, Ott M, Hay DP, Plewes J, Hinds M, LaPradd ML, Bolander H, Vitelli S, Lain M, Brimmer T. The effects of individualized music listening on affective, behavioral, cognitive, and sundowning symptoms of dementia in long-term care residents. J Aging Health. 2022; 34(1): 130-143. doi: 10.1177/08982643211033407.

4. Travers C, Brooks D, Hines S, O'Reilly M, McMaster M, He W, MacAndrew M, Fielding E, Karlsson L, Beattie E. Effectiveness of meaningful occupation interventions for people living with dementia in residential aged care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016; 14(12): 163-225. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003230.

Competing interests: No competing interests

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Music therapy in the treatment of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- 1 Department of Inorganic Chemistry, Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry, Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Biochemistry, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Toledo, Spain

- 2 School of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Toledo, Spain

- 3 Regional Centre for Biomedical Research, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Albacete, Spain

Background: Dementia is a neurological condition characterized by deterioration in cognitive, behavioral, social, and emotional functions. Pharmacological interventions are available but have limited effect in treating many of the disease's features. Several studies have proposed therapy with music as a possible strategy to slow down cognitive decline and behavioral changes associated with aging in combination with the pharmacological therapy.

Objective: We performed a systematic review and subsequent meta-analysis to check whether the application of music therapy in people living with dementia has an effect on cognitive function, quality of life, and/or depressive state.

Methods: The databases used were Medline, PubMed Central, Embase, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. The search was made up of all the literature until present. For the search, key terms, such as “music,” “brain,” “dementia,” or “clinical trial,” were used.

Results: Finally, a total of eight studies were included. All the studies have an acceptable quality based on the score on the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) scales. After meta-analysis, it was shown that the intervention with music improves cognitive function in people living with dementia, as well as quality of life after the intervention and long-term depression. Nevertheless, no evidence was shown of improvement of quality of life in long-term and short-term depression.

Conclusion: Based on our results, music could be a powerful treatment strategy. However, it is necessary to develop clinical trials aimed to design standardized protocols depending on the nature or stage of dementia so that they can be applied together with current cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological therapies.

• Music therapy is used as a treatment for the improvement of cognitive function in people with dementia.

• The intervention based on listening to music presents the greatest effect on patients with dementia followed by singing.

• Music therapy improved the quality of life of people with dementia.

• Music has a long-term effect on depression symptoms associated with dementia.

Introduction

Approximately 50 million people worldwide have dementia, and it is projected to almost triple by 2050 ( 1 ). Dementia is an overall term for diseases and conditions characterized by progressive affectation of cognitive alterations, such as memory and language, as well as behavioral alterations including depression and anxiety ( 2 , 3 ). In order to ameliorate the symptoms of dementia, different intervention approaches, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, have been trialed. Pharmacological interventions, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, are mainly aimed to treat cognitive symptoms but without avoiding the course of the disease. Unfortunately, these therapies have limited effect on alleviating behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia ( 2 , 4 ). On the other hand, non-pharmacological interventions can provide complementary therapy, offering versatile approaches to improve outcomes for people living with dementia and minimize behavioral occurrences as well as to improve or sustain quality of life ( 2 , 5 – 9 ). There are many types of non-pharmacological approaches, such as psychosocial and educational therapies (either with individuals or in groups) and physical or sensorial activities (music, therapeutic touch, and multisensory stimuli) ( 7 , 10 – 12 ). In particular, music therapy is thoroughly used in daily clinical practice in case of dementia ( 13 , 14 ). Many authors emphasize the positive effects of music on the brain. In this sense, several studies showed that people with dementia enjoy music, and their ability to respond to it is preserved even when verbal communication is no longer possible. These studies claimed that interventions based on musical activities have positive effects on behavior, emotion and cognition ( 2 , 15 , 16 ). Therefore, studying and playing music alter brain function and can improve cognitive areas, such as the neural mechanisms for speech ( 17 ), learning, attention ( 18 ), and memory ( 19 ). Music can also activate subcortical circuits, the limbic system, and the emotional reward system, provoking sensations of welfare and pleasure ( 14 ). In this regard, long-term musical training and learning of associated skills can be a strong stimulus for neuroplastic changes, in both the developing brain and the adult brain. These findings suggest the great capacity of music to enhance cerebral plasticity ( 13 , 16 , 20 ). Contrariwise, there are studies that question the specific effect of music therapy on people with dementia ( 21 ). With this background, the aim of this study is to analyze from an unbiased approach the effect of music therapy on the cognitive function, quality of life, and/or depressive state in people living with dementia.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

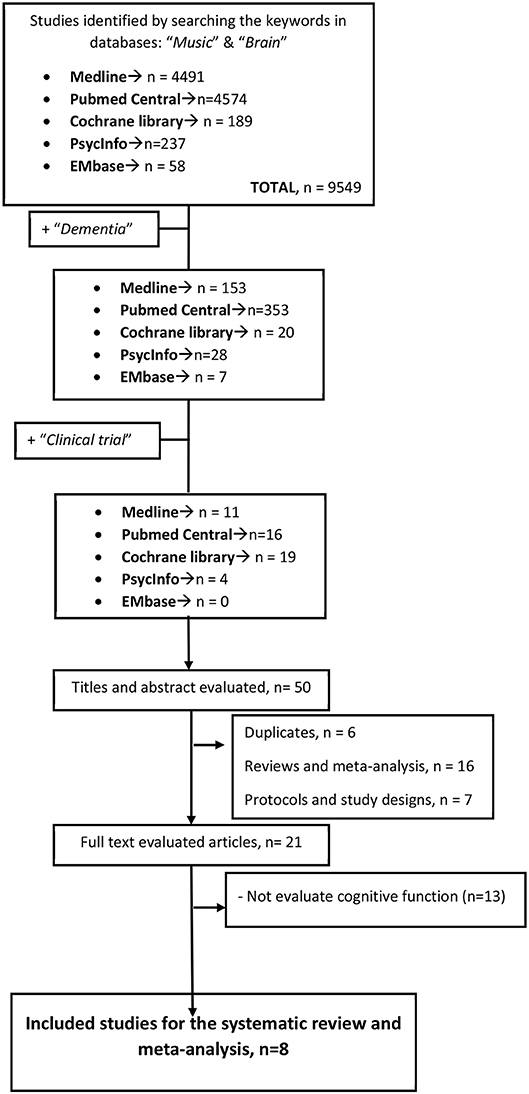

A systematic review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) ( Figure 1 and Searching procedure of Supplementary Data ) ( 22 ). An independent literature search was conducted across Medline, PubMed Central, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane library databases. We carried out the systematic review of the literature following a series of criteria as detailed below.

Figure 1 . Flow of studies through the review process for systematic review and meta-analysis.

Initially, the search began with the terms “brain” and “music.” Later, “dementia” was added, and finally, “clinical trial” was included. The search period used was from 1990 to present. Next, a more in-depth study of selected trials was carried out. Duplicate studies were removed. All studies that compared any form and method of musical intervention with an intervention without music were evaluated. Lastly, those studies that were systematic analysis, reviews, and study protocols and those which do not evaluate cognitive function were excluded. All the trials chosen were designed as randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Data Collection, Extraction, and Quality Assessment

Two authors (CMM and PMM) independently assessed publications for eligibility. Discrepancies or difficulties were discussed with a third review author (CP). Data were collected independently using a standardized data extraction form in order to summarize the characteristics of the studies and outcome data ( 23 ).

From each individual study, we extracted baseline information: publication and year, study design, participants (number, age, and sex ratio), Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score, and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (clinical evaluation of dementia) when possible, as well as the design of each individual study (intervention method, frequency, duration, and time of evaluation of the results) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Characteristics of the studies.

In addition, at the beginning of the study, we assessed the quality of meta-analysis-included studies using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) scale ( Supplementary Tables 1 , 2 of the Supplementary Data ) ( 23 , 32 , 33 ).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome defined to be compared was cognitive function evaluated through MMSE ( 34 ), Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) ( 35 ), Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMBPC) ( 36 ), or Immediate and Deferred Prose Memory test (MPI and MPD, respectively) ( 37 ). Other comparative results, named as secondary outcomes, were quality of life, assessed through Quality of Life in Alzheimer's Disease (QOL-AD) ( 38 ), and depression, evaluated through Cornell–Brown Scale for Quality of Life in Dementia (CBS) and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) ( 39 , 40 ).

Statistical Analysis: Meta-Analysis

First, a comparison was made using the random-effects model. All outcomes were continuous variables [mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the change in the score before and after the therapy in the different diagnostic tests], and the standardized mean difference (SMD) was analyzed. All the analyses were carried out considering a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. Statistical heterogeneity was also tested by I 2 . I 2 <25% was identified as low heterogeneity ( 41 , 42 ). Finally, the publication bias was evaluated using funnel plot graphs ( 43 , 44 ). To further investigate the heterogeneity, meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to assess the primary outcome data and associations according to the method of intervention (interactive and passive), trial period, number of sessions per week, and effect of evaluation method used. The P values in the meta-regression revealed the overall significance of the influence factors.

Meta-analysis, heterogeneity study, and graphical representations were performed using R with the Metafor package ( 44 ). To digitize graphics and obtain numerical data from those trials that did not provide them, the GetData Graph Digitizer program ( Getdata-graph-digitizer.com ) was used.

Baseline Characteristics

Results of initial search and exclusions are shown in Figure 1 . A thorough reading of each article was carried out, and a summary of each of them is shown in Table 1 . Therefore, we finally stayed for the systematic review and meta-analysis with eight articles. The size of the studies was between 30 and 201 subjects, with a total of 816 subjects with mild to severe dementia, assigned randomly to both the intervention and control groups. All the people in the trials stayed in nursing homes or hospitals. Särkämö et al. divided the participants into three groups, an active group that sang, a passive group that listened to music, and a control group ( 24 , 25 ). On the other hand, Doi et al. evaluated two cognitive programs of leisure activities: dancing and playing musical instruments ( 26 ). Furthermore, Han et al. tested a multimodal cognitive improvement therapy (MCET) consisting of cognitive training, cognitive stimulation, reality orientation, physical, reminiscence, and music therapy against a sham therapy without music ( 27 ). In this line, Ceccato et al. tried the program Sound Training for Attention and Memory in Dementia (STAM-Dem), a manualized music-based protocol designed to be used in the rehabilitation of cognitive functions in people with dementia. Those in the control group continued with the normal “standard care” provided ( 28 ). While Lyu et al. compared the effect of singing on cognitive function and mood, Chu et al. assessed a protocol that includes playing an instrument, dancing, and listening to music. The effect size of all those studies reveals a general improvement in the results of the experimental group ( 29 , 30 ). Finally, Guétin et al. did not find a significant difference between the experimental and control groups when evaluating the cognitive function after an 18-month therapy based on listening to music ( 31 ).

All the studies had an acceptable quality as confirmed after applying the PEDro and CASP scales ( Supplementary Tables 1 , 2 , respectively, of the Supplementary Data ).

In case of medication (dementia, antipsychotic, and antidepressant medication and sedative or sleeping medication), it must have been stable prior to the trial. Since participants were randomized, there were no significant differences between the control and music-treated groups with regard to medication. Likewise, there were no significant differences between groups in the dementia severity and/or demographic variables.

Efficacy of Musical Intervention in Cognitive Function

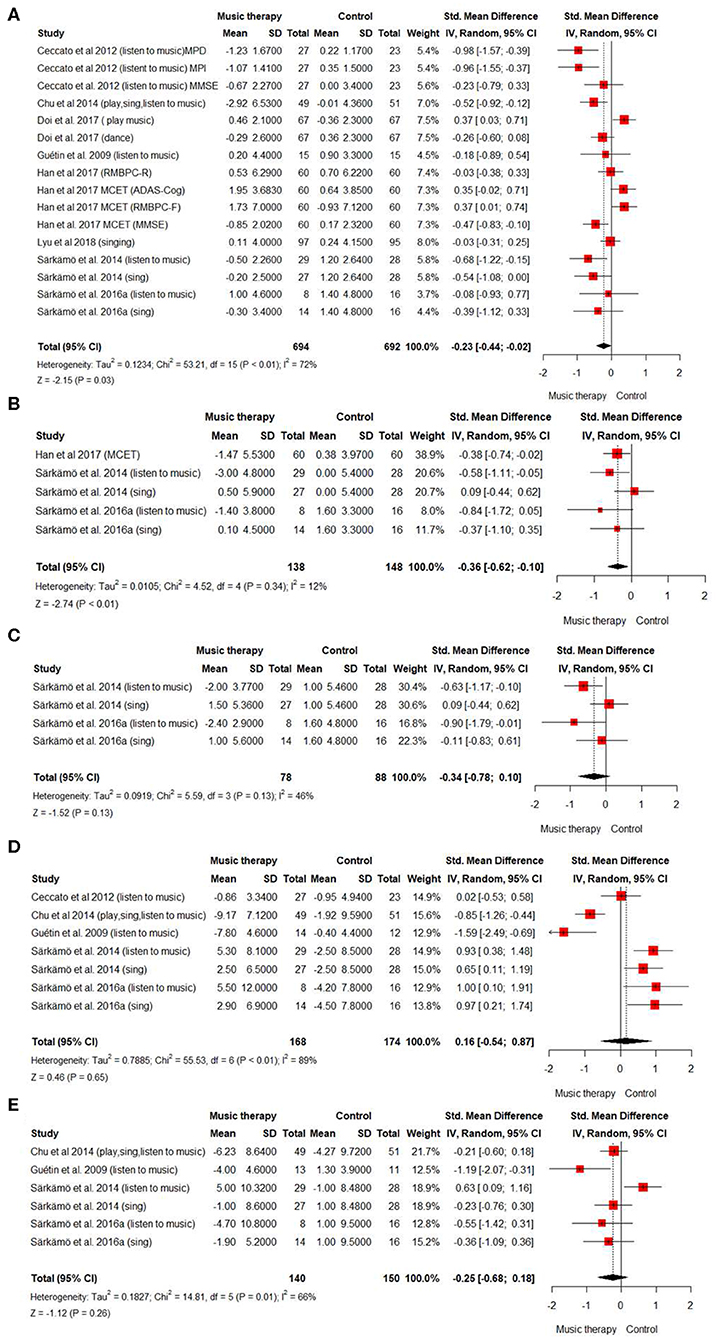

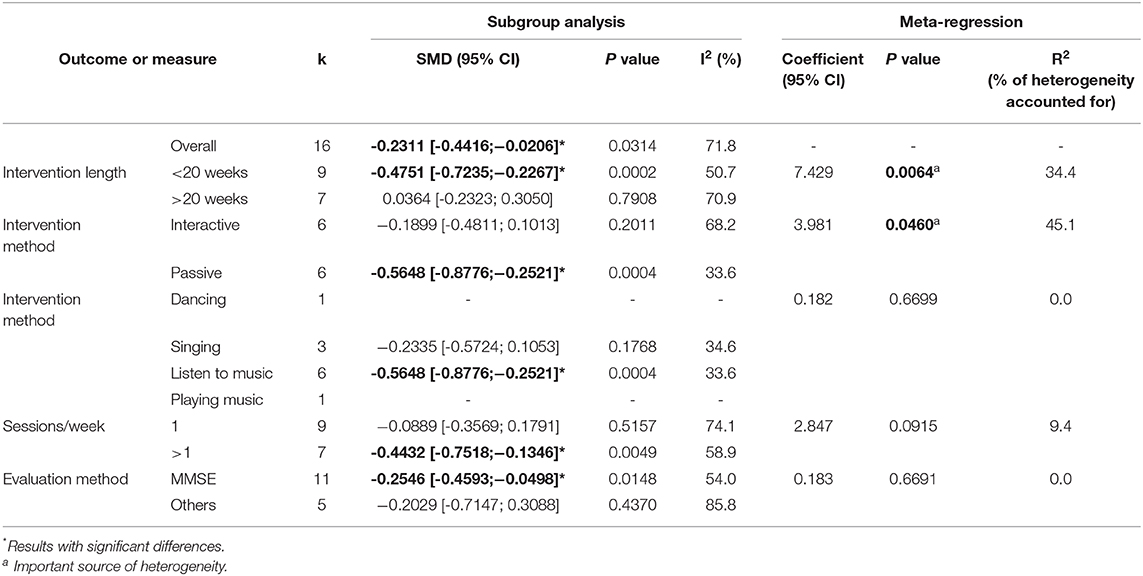

Figure 2 summarizes the relevant results of the quantitative synthesis of the effect of music therapy for people living with dementia. First, we evaluated the effect of music therapy on cognitive function by analyzing eight studies (816 cases) ( Figure 2A ). In the random-effects model, SMD was −0.23 (95% CI: −0.44, −0.02), which suggested that musical intervention could be beneficial to improve cognitive function in people living with dementia. However, the trials showed very high heterogeneity [ I 2 value = 72% ( P < 0.0001)].

Figure 2 . Summary of efficacy of music intervention on cognitive function and secondary outcomes. Forest plot. Overall efficacy of music intervention in people with dementia (A) on cognitive function. (B) on quality of life. (C) on quality of life of people after 6 months of treatment. (D) on depressive state (E) on depressive state after 6 months.

Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were used to further explore this source of heterogeneity ( Table 2 ). Two significant sources of heterogeneity were detected: the trial period and the intervention method (coefficient = 7.43, P = 0.006 and coefficient = 3.981; P = 0.046, respectively). Interestingly, we observed that shorter intervention periods (<20 weeks) and passive interventions methods (listening to music) had greater effect on people living with dementia than longer intervention periods or interactive interventions, such as singing and dancing ( Figure 2A ; Table 2 ). On the other hand, to play an instrument does not seem to have a positive effect on cognitive function. Nevertheless, it appears to be effective when it is combined with singing and listening to music, without improving the effect of just listening to music ( Figure 2A ). The funnel plot on the publication bias across cognitive studies appeared symmetrically low ( Supplementary Figure 1 of the Supplementary Data ).

Table 2 . Meta-regression for the effect of music intervention vs. control on cognitive function.

Efficacy of Musical Intervention in Quality of Life

A meta-analysis about the quality of life of people living with dementia after the intervention with music therapy was designed. The analysis included three studies (286 cases). The results suggested that there was an effect on the quality of life of patients once the intervention is finished (SMD = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.62, 0.10) ( Figure 2B ). On the other hand, no significant effect of music therapy was observed when carrying out the analysis (two studies; 166 cases) of the quality of life of people living with dementia 6 months after the intervention (SMD = −0.34, 95% CI: −0.78, 0.10) ( Figure 2C ). The heterogeneity of the studies was small in the short-term analysis but >25 in the long term ( I 2 = 12 and I 2 = 42, respectively).

Supplementary Figures 1B,C in the Supplementary Data represent the funnel plot about the quality of life measured after the intervention and 6 months later. Data indicate that there is no publication bias.

Efficacy of Musical Intervention in the Depressive State

Finally, in order to evaluate the influence of music therapy on the depressive state associated with dementia, in both the short and long terms, we analyzed its effect when the intervention had just ended and 6 months after the treatment. The result of the meta-analysis (5 studies, 342 cases) suggested that there was no short-term effect on the depressive state of the patients (SMD = 0.16, 95% CI: −0.54, 0.87) ( Figure 2D ). However, when studying the depressive state of patients 6 months after the intervention to know if there is a long-term effect (4 studies, 290 cases), the result indicated that music therapy could have a positive effect on the depressive state of people living with dementia (SMD = −0.25, 95% CI: −0.68, 0.18) ( Figure 2E ). In both cases, the heterogeneity of the studies was high [ I 2 = 89% ( P < 0.0001) in the short term; I 2 = 66% ( P < 0.01) in the long term]. The funnel plot of the depressive state after the intervention and about the depressive state at 6 months denotes that there is no publication bias ( Supplementary Figures 1D,E in the Supplementary Data ).

The main objective of this work was to study through systematic review and meta-analysis whether the application of music as a therapy has an effect on cognitive function, quality of life, and/or depressive state in a group of specific diseases such as dementia. Nowadays, there is a growing incidence of this pathology in the population ( 1 ), and therefore, it is necessary to develop treatments and activities to relieve its symptoms. In addition, there is not enough scientific evidence about the efficacy of music as a therapy on the cognitive and behavioral states of these patients.

Our results suggest that music therapy has a positive effect on cognitive function for people living with dementia. To reach that assumption, we performed a comprehensive systematic review that includes eight studies with 816 subjects. We observed that listening to music is the intervention type with the greatest positive effect on cognitive function. This could be explained because listening to music integrates perception of sounds, rhythms, and lyrics and the response to the sound and requires attention to an environment, which implies that our brain has many areas activated. Those events are linked to wide cortical activation ( 14 , 15 , 45 ). In addition, music training is a strong stimulus for neuroplastic changes. So music could decrease neuronal degeneration by enhancing cerebral plasticity and inducing the creation of new connections in the brain ( 46 , 47 ). However, the heterogeneity presented by the different studies included in the meta-analysis does not allow us to reach reliable conclusions ( I 2 = 75%). This heterogeneity may be due to the design of each study, the difference in the type of intervention carried out, and the number of participants among other variables ( 41 ). Meta-regression showed that the intervention method, interactive or passive, is a significant source of heterogeneity accounting for 45.1% of the total heterogeneity detected ( Table 2 ). We observed a significant effect on cognitive function in the passive intervention group ( P = 0.0004). This result is in agreement with our previous analysis where listening to music has the greatest effect. Other sources of heterogeneity found when we analyzed the effect of music therapy on the cognitive function were the intervention length and the number of sessions per week (34.4 and 9.4%, respectively), the latter not being significant ( Table 2 ). Based on the literature, there is a huge diversity in the scheduling of music treatment duration. In our case, sessions varied from 90 min once a week during 10 or 20 weeks to 60 min during 40 weeks. It seems that the length for the entire music intervention procedure might be a crucial element for successful results and seems to be associated with the intervention type ( 48 – 50 ). We observed that shorter intervention periods (<20 weeks) had a greater effect on people living with dementia than longer intervention ones. This finding is not enough to draw further conclusion due to the heterogeneity found. According to our results, although the number of sessions per week seems not to have an impact on music therapy effectiveness, a greater frequency of therapy seems to be of particular importance ( 48 ).

Xu et al. and Roman-Caballero et al. showed similar results in two meta-analysis studies conducted on musical intervention in cognitive dysfunction in healthy older adults ( 18 , 23 ). In fact, as in our study, the level of heterogeneity found was also very wide. Van der Steen et al. also analyzed music-based therapeutic intervention on cognition in people with dementia ( 51 ). They found low-quality evidence that music-based therapeutic interventions may have little or no effect on cognition. Nevertheless, they did not analyze the effects in relation to the overall duration of the treatment, the number of sessions, and the type of music intervention.

After analysis of the secondary outcomes, music therapy surprisingly did not have a marked effect. Regarding quality of life, our data suggested a positive effect once the therapy is finished, but it was not durable after 6 months of music intervention. On the other hand, the study evaluating the effect of music therapy on the depressive state of people living with dementia showed no improvement in the state of these patients when they were evaluated after the intervention. However, if the depressive state was evaluated after 6 months from treatment, a shift in favor of music therapy was observed. This result suggests that the effects of music are not immediate and that the design of progressive and continuous interventions is necessary in order to obtain successful results as has also been discussed by Leubner and Hinterberger ( 49 ).

Xu et al. observed that, both in the analysis of the depressive state and in the quality of life, music therapy does not have a positive effect ( 23 ). These data corroborate the results obtained in the short term in our study. However, they did not measure the effects of long-term music therapy. Furthermore, Dyer et al. found that music as a non-pharmacological intervention improves behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia but concluded that further research is required ( 2 , 52 ). Van der Steen et al. also compared the effect music-based therapeutic intervention versus usual care or versus other activities on depression and emotional well-being ( 51 ). Likewise, at the end of treatment, they found low-quality evidence that the musical interventions may improve emotional well-being and quality of life.

Music is a pleasant stimulus, especially when it is adapted to one's personal preferences, and it can evoke positive emotions. Some studies have demonstrated that music therapy had an influence on levels of hormones such as cortisol. It also affects the autonomic nervous systems by decreasing stress-related activation ( 53 , 54 ). At the same time, some studies suggest that music promotes several neurotransmitters, such as endorphins, endocannabinoids, dopamine, and nitric oxide. This implies that music takes part in reward, stress, and arousal processes ( 55 ). However, the lack of standardized methods for musical stimulus selection is a common feature in the studies we have reviewed. Additionally, the absence of a suitable control of the intervention to match levels of arousal, attentional engagement, mood state modification, or emotional qualities between participants may be a reason for the differences between studies ( 55 ). Furthermore, our results have likely been influenced by the type of test used to evaluate depression symptoms. Most studies used questionnaires that were based on self-assessment. However, it is unclear whether this approach is valid to detect changes regarding symptom improvement. Future approaches should add measurements of physiological body reactions, such as skin conductance and heart rate, for more objectivity ( 49 ).

Conclusions

This study shows evidence with a positive trend supporting music therapy for the improvement of cognitive function in people living with dementia. Additionally, the study reveals a positive result for treatment of long-term depression, without showing an effect on short-term depression in these patients. Furthermore, music therapy seems to improve quality of life of people with dementia once the intervention is finished, but it does not have a long-lasting effect.

Limitations And Potential Explanations

This meta-analysis had several limitations. First, there are many clinical trials in development like NCT03496675 and NCT03271190 ( Clinicaltrials.gov ), whose completion is estimated to be in 2024 and 2022, respectively, which could not be included in this analysis ( 56 , 57 ). Secondly, there are several important limitations in the design of the trials included. First, some of the studies included had a very small sample size (<100 participants), which means that they may lack enough participants to detect differences between groups. Also, the musical interventions and the method used to evaluate the cognitive function and depression were diverse and make it difficult to state clearly their benefit when compared to usual care. The lack of standardized methods for musical stimulus selection is a common drawback in the studies we reviewed and a probable contributor to inconsistencies across studies ( 55 ).

Finally, we could not perform a subgroup analysis regarding dementia severity to evaluate when music intervention would be more appropriate in the disease trajectory. This was due to the fact that in all studies selected, participants with different dementia stage were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. Besides, almost all trials in the literature were focused on the mild or moderate stage of dementia, and there were few studies about people living with severe dementia. However, those studies do not evaluate cognitive function ( 58 ).

Future Research Recommendation

Despite the limitations, music is a non-pharmacological intervention, noninvasive, and without side effects, and its application is economical ( 53 , 54 ). For this reason, in order to confirm the effect of musical interventions, more clinical trials on the effect of music therapy should be promoted. The tests should include a high number of participants, be robust, and be randomized. As explained, music therapy methods and techniques used in clinical practice are diverse. Therefore, it is necessary to design standardized clinical trials that evaluate cognitive function and the disease behavioral features through the same battery of tests to obtain comparable results. On the other hand, there were no high-quality longitudinal studies that demonstrated long-term benefits of music therapy. It is also important to develop study designs that will be sensitive to the nature and severity of dementia. Future music therapy studies need to define a theoretical model, include better-focused outcome measures, and discuss how the findings may improve the well-being of people with dementia as discussed by McDermott et al. ( 45 ). and many others ( 49 , 54 , 55 ).

The investment in research in this novel therapy could lead to its implementation as a new and alternative intervention together with current cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological therapies.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material .

Author Contributions

CM-M and PM-M: did systematic review and review the manuscript. CM-M and RC: meta-analysis. RC: meta-regression and sub-group analysis and review the manuscript. CP: design the study, conceptualization, supervision, wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2020.00160/full#supplementary-material

1. WHO. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025 . Geneva: World Health Organization (2017). p. 52. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/action_plan_2017_2025/en/

2. Dyer SM, Harrison SL, Laver K, Whitehead C, Crotty M. An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatrics. (2018) 30:295–309. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217002344

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Kolanowski A, Boltz M, Galik E, Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Resnick B, et al. Determinants of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a scoping review of the evidence. Nurs Outlook . (2017) 65:515–29. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.06.006

4. Laver K, Dyer S, Whitehead C, Clemson L, Crotty M. Interventions to delay functional decline in people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:10767. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010767

5. Olazarán J, Cruz BR, Isabel LC, Cruz I, Peña-Casanova J, Del Ser T, et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2010) 30:161–78. doi: 10.1159/000316119

6. Chalfont G, Milligan C, Simpson J. A mixed methods systematic review of multimodal non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognition for people with dementia. Dementia. (2018) 19:9. doi: 10.1177/1471301218795289

7. Lorusso LN, Bosch SJ. Impact of multisensory environments on behavior for people with dementia: a systematic literature review. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:e168–e79. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw168

8. Oliveira AM de, Radanovic M, Mello PCH de, Buchain PC, Vizzotto AD, Celestino DL, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. (2015) 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2015/218980

9. Cations M, May N, Crotty M, Low LF, Clemson L, Whitehead C, et al. Health professional perspectives on rehabilitation for people with dementia. Gerontologist. (2019) 60:503–12. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz007

10. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. (2015) 350(mar02 7):h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369

11. Tak SH, Zhang H, Patel H, Hong SH. Computer activities for persons with dementia. Gerontologist. (2015) 55:S140–S9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv003

12. Regier NG, Hodgson NA, Gitlin LN. Characteristics of activities for persons with dementia at the mild, moderate, and severe stages. Gerontologist. (2017) 57:987–97. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw133

13. Altenmüller E, Schlaug G. Apollo's gift: new aspects of neurologic music therapy. Prog Brain Res. (2015) 217:237–52. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.029

14. Soria-Urios G, Duque P, García-Moreno JM. Music and brain. Rev Neurol. (2011) 53:739–46. doi: 10.33588/rn.5312.2011475

15. Gaser C, Schlaug G. Brain structures differ between musicians and non-musicians. J Neurosci. (2003) 23:9240–5. doi: 10.1016/23/27/9240

16. Schlaug G. Musicians and music making as a model for the study of brain plasticity. Prog Brain Res . (2015) 217: 37–55. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.020

17. Musacchia G, Sams M, Skoe E, Kraus N. Musicians have enhanced subcortical auditory and audiovisual processing of speech and music. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . (2007) 104:15894–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701498104

18. Román-Caballero R, Arnedo M, Triviño M, Lupiáñez J. Musical practice as an enhancer of cognitive function in healthy aging - a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e207957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207957

19. Gooding LF, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA. Musical training and late-life cognition. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. (2014) 29:333–43. doi: 10.1177/1533317513517048

20. Perrone-Capano C, Volpicelli F, di Porzio U. Biological bases of human musicality. Rev Neurosci. (2017) 28:235–45. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0046

21. Baird A, Samson S. Music and dementia. Prog Brain Res. (2015) 217:207–35. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.028

22. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

23. Xu B, Sui Y, Zhu C, Yang X, Zhou J, Li L, et al. Music intervention on cognitive dysfunction in healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. (2017) 38:983–92. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2878-9

24. Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist. (2014) 54:634–50. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt100

25. Särkämö T, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, Rantanen P. Pattern of emotional benefits induced by regular singing and music listening in dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2016) 64:439–40. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13963

26. Doi T, Verghese J, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, et al. Effects of cognitive leisure activity on cognition in mild cognitive impairment: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18:686–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.013

27. Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: a multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2017) 55:787–96. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160619

28. Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia: A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. (2012) 27:301–10. doi: 10.1177/1533317512452038

29. Lyu J, Zhang J, Mu H, Li W, Champ M, Xiong Q, et al. The effects of music therapy on cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. (2018) 64:1347–58. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180183

30. Chu H, Yang CY, Lin Y, Ou KL, Lee TY, O'Brien AP, et al. The impact of group music therapy on depression and cognition in elderly persons with dementia: a randomized controlled study. Biol Res Nurs. (2014) 16:209–17. doi: 10.1177/1099800413485410

31. Guétin S, Portet F, Picot MC, Pommié C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer's type dementia: randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2009) 28:36–46. doi: 10.1159/000229024

32. de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother. (2009) 55:129–33. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(09)70043-1