Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.

- A case study seeks to identify the best possible solution to a research problem; case analysis can have an indeterminate set of solutions or outcomes . Your role in studying a case is to discover the most logical, evidence-based ways to address a research problem. A case analysis assignment rarely has a single correct answer because one of the goals is to force students to confront the real life dynamics of uncertainly, ambiguity, and missing or conflicting information within professional practice. Under these conditions, a perfect outcome or solution almost never exists.

- Case study is unbounded and relies on gathering external information; case analysis is a self-contained subject of analysis . The scope of a case study chosen as a method of research is bounded. However, the researcher is free to gather whatever information and data is necessary to investigate its relevance to understanding the research problem. For a case analysis assignment, your professor will often ask you to examine solutions or recommended courses of action based solely on facts and information from the case.

- Case study can be a person, place, object, issue, event, condition, or phenomenon; a case analysis is a carefully constructed synopsis of events, situations, and behaviors . The research problem dictates the type of case being studied and, therefore, the design can encompass almost anything tangible as long as it fulfills the objective of generating new knowledge and understanding. A case analysis is in the form of a narrative containing descriptions of facts, situations, processes, rules, and behaviors within a particular setting and under a specific set of circumstances.

- Case study can represent an open-ended subject of inquiry; a case analysis is a narrative about something that has happened in the past . A case study is not restricted by time and can encompass an event or issue with no temporal limit or end. For example, the current war in Ukraine can be used as a case study of how medical personnel help civilians during a large military conflict, even though circumstances around this event are still evolving. A case analysis can be used to elicit critical thinking about current or future situations in practice, but the case itself is a narrative about something finite and that has taken place in the past.

- Multiple case studies can be used in a research study; case analysis involves examining a single scenario . Case study research can use two or more cases to examine a problem, often for the purpose of conducting a comparative investigation intended to discover hidden relationships, document emerging trends, or determine variations among different examples. A case analysis assignment typically describes a stand-alone, self-contained situation and any comparisons among cases are conducted during in-class discussions and/or student presentations.

The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017; Crowe, Sarah et al. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (2011): doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Works

- Next: Writing a Case Study >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Libr Assoc

- v.107(1); 2019 Jan

Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type

The purpose of this editorial is to distinguish between case reports and case studies. In health, case reports are familiar ways of sharing events or efforts of intervening with single patients with previously unreported features. As a qualitative methodology, case study research encompasses a great deal more complexity than a typical case report and often incorporates multiple streams of data combined in creative ways. The depth and richness of case study description helps readers understand the case and whether findings might be applicable beyond that setting.

Single-institution descriptive reports of library activities are often labeled by their authors as “case studies.” By contrast, in health care, single patient retrospective descriptions are published as “case reports.” Both case reports and case studies are valuable to readers and provide a publication opportunity for authors. A previous editorial by Akers and Amos about improving case studies addresses issues that are more common to case reports; for example, not having a review of the literature or being anecdotal, not generalizable, and prone to various types of bias such as positive outcome bias [ 1 ]. However, case study research as a qualitative methodology is pursued for different purposes than generalizability. The authors’ purpose in this editorial is to clearly distinguish between case reports and case studies. We believe that this will assist authors in describing and designating the methodological approach of their publications and help readers appreciate the rigor of well-executed case study research.

Case reports often provide a first exploration of a phenomenon or an opportunity for a first publication by a trainee in the health professions. In health care, case reports are familiar ways of sharing events or efforts of intervening with single patients with previously unreported features. Another type of study categorized as a case report is an “N of 1” study or single-subject clinical trial, which considers an individual patient as the sole unit of observation in a study investigating the efficacy or side effect profiles of different interventions. Entire journals have evolved to publish case reports, which often rely on template structures with limited contextualization or discussion of previous cases. Examples that are indexed in MEDLINE include the American Journal of Case Reports , BMJ Case Reports, Journal of Medical Case Reports, and Journal of Radiology Case Reports . Similar publications appear in veterinary medicine and are indexed in CAB Abstracts, such as Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Record Case Reports .

As a qualitative methodology, however, case study research encompasses a great deal more complexity than a typical case report and often incorporates multiple streams of data combined in creative ways. Distinctions include the investigator’s definitions and delimitations of the case being studied, the clarity of the role of the investigator, the rigor of gathering and combining evidence about the case, and the contextualization of the findings. Delimitation is a term from qualitative research about setting boundaries to scope the research in a useful way rather than describing the narrow scope as a limitation, as often appears in a discussion section. The depth and richness of description helps readers understand the situation and whether findings from the case are applicable to their settings.

CASE STUDY AS A RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Case study as a qualitative methodology is an exploration of a time- and space-bound phenomenon. As qualitative research, case studies require much more from their authors who are acting as instruments within the inquiry process. In the case study methodology, a variety of methodological approaches may be employed to explain the complexity of the problem being studied [ 2 , 3 ].

Leading authors diverge in their definitions of case study, but a qualitative research text introduces case study as follows:

Case study research is defined as a qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bound systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information, and reports a case description and case themes. The unit of analysis in the case study might be multiple cases (a multisite study) or a single case (a within-site case study). [ 4 ]

Methodologists writing core texts on case study research include Yin [ 5 ], Stake [ 6 ], and Merriam [ 7 ]. The approaches of these three methodologists have been compared by Yazan, who focused on six areas of methodology: epistemology (beliefs about ways of knowing), definition of cases, design of case studies, and gathering, analysis, and validation of data [ 8 ]. For Yin, case study is a method of empirical inquiry appropriate to determining the “how and why” of phenomena and contributes to understanding phenomena in a holistic and real-life context [ 5 ]. Stake defines a case study as a “well-bounded, specific, complex, and functioning thing” [ 6 ], while Merriam views “the case as a thing, a single entity, a unit around which there are boundaries” [ 7 ].

Case studies are ways to explain, describe, or explore phenomena. Comments from a quantitative perspective about case studies lacking rigor and generalizability fail to consider the purpose of the case study and how what is learned from a case study is put into practice. Rigor in case studies comes from the research design and its components, which Yin outlines as (a) the study’s questions, (b) the study’s propositions, (c) the unit of analysis, (d) the logic linking the data to propositions, and (e) the criteria for interpreting the findings [ 5 ]. Case studies should also provide multiple sources of data, a case study database, and a clear chain of evidence among the questions asked, the data collected, and the conclusions drawn [ 5 ].

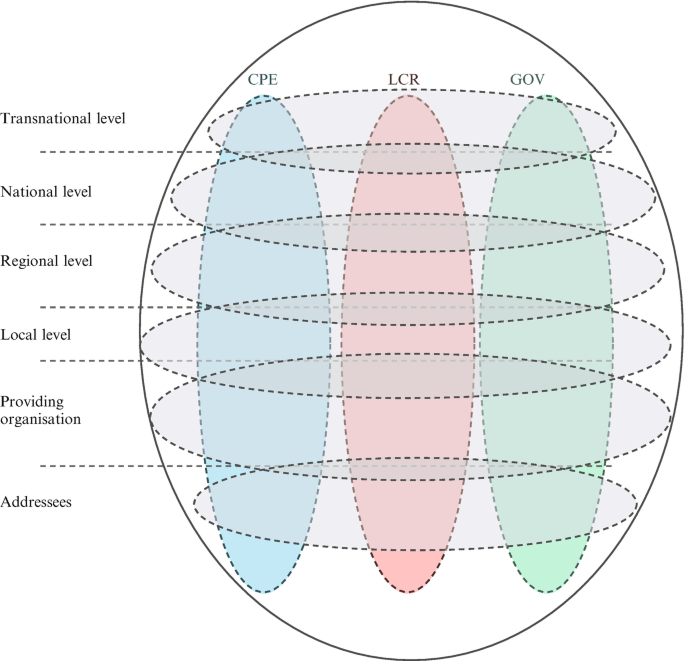

Sources of evidence for case studies include interviews, documentation, archival records, direct observations, participant-observation, and physical artifacts. One of the most important sources for data in qualitative case study research is the interview [ 2 , 3 ]. In addition to interviews, documents and archival records can be gathered to corroborate and enhance the findings of the study. To understand the phenomenon or the conditions that created it, direct observations can serve as another source of evidence and can be conducted throughout the study. These can include the use of formal and informal protocols as a participant inside the case or an external or passive observer outside of the case [ 5 ]. Lastly, physical artifacts can be observed and collected as a form of evidence. With these multiple potential sources of evidence, the study methodology includes gathering data, sense-making, and triangulating multiple streams of data. Figure 1 shows an example in which data used for the case started with a pilot study to provide additional context to guide more in-depth data collection and analysis with participants.

Key sources of data for a sample case study

VARIATIONS ON CASE STUDY METHODOLOGY

Case study methodology is evolving and regularly reinterpreted. Comparative or multiple case studies are used as a tool for synthesizing information across time and space to research the impact of policy and practice in various fields of social research [ 9 ]. Because case study research is in-depth and intensive, there have been efforts to simplify the method or select useful components of cases for focused analysis. Micro-case study is a term that is occasionally used to describe research on micro-level cases [ 10 ]. These are cases that occur in a brief time frame, occur in a confined setting, and are simple and straightforward in nature. A micro-level case describes a clear problem of interest. Reporting is very brief and about specific points. The lack of complexity in the case description makes obvious the “lesson” that is inherent in the case; although no definitive “solution” is necessarily forthcoming, making the case useful for discussion. A micro-case write-up can be distinguished from a case report by its focus on briefly reporting specific features of a case or cases to analyze or learn from those features.

DATABASE INDEXING OF CASE REPORTS AND CASE STUDIES

Disciplines such as education, psychology, sociology, political science, and social work regularly publish rich case studies that are relevant to particular areas of health librarianship. Case reports and case studies have been defined as publication types or subject terms by several databases that are relevant to librarian authors: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ERIC. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA) does not have a subject term or publication type related to cases, despite many being included in the database. Whereas “Case Reports” are the main term used by MEDLINE’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and PsycINFO’s thesaurus, CINAHL and ERIC use “Case Studies.”

Case reports in MEDLINE and PsycINFO focus on clinical case documentation. In MeSH, “Case Reports” as a publication type is specific to “clinical presentations that may be followed by evaluative studies that eventually lead to a diagnosis” [ 11 ]. “Case Histories,” “Case Studies,” and “Case Study” are all entry terms mapping to “Case Reports”; however, guidance to indexers suggests that “Case Reports” should not be applied to institutional case reports and refers to the heading “Organizational Case Studies,” which is defined as “descriptions and evaluations of specific health care organizations” [ 12 ].

PsycINFO’s subject term “Case Report” is “used in records discussing issues involved in the process of conducting exploratory studies of single or multiple clinical cases.” The Methodology index offers clinical and non-clinical entries. “Clinical Case Study” is defined as “case reports that include disorder, diagnosis, and clinical treatment for individuals with mental or medical illnesses,” whereas “Non-clinical Case Study” is a “document consisting of non-clinical or organizational case examples of the concepts being researched or studied. The setting is always non-clinical and does not include treatment-related environments” [ 13 ].

Both CINAHL and ERIC acknowledge the depth of analysis in case study methodology. The CINAHL scope note for the thesaurus term “Case Studies” distinguishes between the document and the methodology, though both use the same term: “a review of a particular condition, disease, or administrative problem. Also, a research method that involves an in-depth analysis of an individual, group, institution, or other social unit. For material that contains a case study, search for document type: case study.” The ERIC scope note for the thesaurus term “Case Studies” is simple: “detailed analyses, usually focusing on a particular problem of an individual, group, or organization” [ 14 ].

PUBLICATION OF CASE STUDY RESEARCH IN LIBRARIANSHIP

We call your attention to a few examples published as case studies in health sciences librarianship to consider how their characteristics fit with the preceding definitions of case reports or case study research. All present some characteristics of case study research, but their treatment of the research questions, richness of description, and analytic strategies vary in depth and, therefore, diverge at some level from the qualitative case study research approach. This divergence, particularly in richness of description and analysis, may have been constrained by the publication requirements.

As one example, a case study by Janke and Rush documented a time- and context-bound collaboration involving a librarian and a nursing faculty member [ 15 ]. Three objectives were stated: (1) describing their experience of working together on an interprofessional research team, (2) evaluating the value of the librarian role from librarian and faculty member perspectives, and (3) relating findings to existing literature. Elements that signal the qualitative nature of this case study are that the authors were the research participants and their use of the term “evaluation” is reflection on their experience. This reads like a case study that could have been enriched by including other types of data gathered from others engaging with this team to broaden the understanding of the collaboration.

As another example, the description of the academic context is one of the most salient components of the case study written by Clairoux et al., which had the objectives of (1) describing the library instruction offered and learning assessments used at a single health sciences library and (2) discussing the positive outcomes of instruction in that setting [ 16 ]. The authors focus on sharing what the institution has done more than explaining why this institution is an exemplar to explore a focused question or understand the phenomenon of library instruction. However, like a case study, the analysis brings together several streams of data including course attendance, online material page views, and some discussion of results from surveys. This paper reads somewhat in between an institutional case report and a case study.

The final example is a single author reporting on a personal experience of creating and executing the role of research informationist for a National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded research team [ 17 ]. There is a thoughtful review of the informationist literature and detailed descriptions of the institutional context and the process of gaining access to and participating in the new role. However, the motivating question in the abstract does not seem to be fully addressed through analysis from either the reflective perspective of the author as the research participant or consideration of other streams of data from those involved in the informationist experience. The publication reads more like a case report about this informationist’s experience than a case study that explores the research informationist experience through the selection of this case.

All of these publications are well written and useful for their intended audiences, but in general, they are much shorter and much less rich in depth than case studies published in social sciences research. It may be that the authors have been constrained by word counts or page limits. For example, the submission category for Case Studies in the Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) limited them to 3,000 words and defined them as “articles describing the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating a new service, program, or initiative, typically in a single institution or through a single collaborative effort” [ 18 ]. This definition’s focus on novelty and description sounds much more like the definition of case report than the in-depth, detailed investigation of a time- and space-bound problem that is often examined through case study research.

Problem-focused or question-driven case study research would benefit from the space provided for Original Investigations that employ any type of quantitative or qualitative method of analysis. One of the best examples in the JMLA of an in-depth multiple case study that was authored by a librarian who published the findings from her doctoral dissertation represented all the elements of a case study. In eight pages, she provided a theoretical basis for the research question, a pilot study, and a multiple case design, including integrated data from interviews and focus groups [ 19 ].

We have distinguished between case reports and case studies primarily to assist librarians who are new to research and critical appraisal of case study methodology to recognize the features that authors use to describe and designate the methodological approaches of their publications. For researchers who are new to case research methodology and are interested in learning more, Hancock and Algozzine provide a guide [ 20 ].

We hope that JMLA readers appreciate the rigor of well-executed case study research. We believe that distinguishing between descriptive case reports and analytic case studies in the journal’s submission categories will allow the depth of case study methodology to increase. We also hope that authors feel encouraged to pursue submitting relevant case studies or case reports for future publication.

Editor’s note: In response to this invited editorial, the Journal of the Medical Library Association will consider manuscripts employing rigorous qualitative case study methodology to be Original Investigations (fewer than 5,000 words), whereas manuscripts describing the process of developing, implementing, and assessing a new service, program, or initiative—typically in a single institution or through a single collaborative effort—will be considered to be Case Reports (formerly known as Case Studies; fewer than 3,000 words).

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/