How to Write the Community Essay – Guide with Examples (2023-24)

September 6, 2023

Students applying to college this year will inevitably confront the community essay. In fact, most students will end up responding to several community essay prompts for different schools. For this reason, you should know more than simply how to approach the community essay as a genre. Rather, you will want to learn how to decipher the nuances of each particular prompt, in order to adapt your response appropriately. In this article, we’ll show you how to do just that, through several community essay examples. These examples will also demonstrate how to avoid cliché and make the community essay authentically and convincingly your own.

Emphasis on Community

Do keep in mind that inherent in the word “community” is the idea of multiple people. The personal statement already provides you with a chance to tell the college admissions committee about yourself as an individual. The community essay, however, suggests that you depict yourself among others. You can use this opportunity to your advantage by showing off interpersonal skills, for example. Or, perhaps you wish to relate a moment that forged important relationships. This in turn will indicate what kind of connections you’ll make in the classroom with college peers and professors.

Apart from comprising numerous people, a community can appear in many shapes and sizes. It could be as small as a volleyball team, or as large as a diaspora. It could fill a town soup kitchen, or spread across five boroughs. In fact, due to the internet, certain communities today don’t even require a physical place to congregate. Communities can form around a shared identity, shared place, shared hobby, shared ideology, or shared call to action. They can even arise due to a shared yet unforeseen circumstance.

What is the Community Essay All About?

In a nutshell, the community essay should exhibit three things:

- An aspect of yourself, 2. in the context of a community you belonged to, and 3. how this experience may shape your contribution to the community you’ll join in college.

It may look like a fairly simple equation: 1 + 2 = 3. However, each college will word their community essay prompt differently, so it’s important to look out for additional variables. One college may use the community essay as a way to glimpse your core values. Another may use the essay to understand how you would add to diversity on campus. Some may let you decide in which direction to take it—and there are many ways to go!

To get a better idea of how the prompts differ, let’s take a look at some real community essay prompts from the current admission cycle.

Sample 2023-2024 Community Essay Prompts

1) brown university.

“Students entering Brown often find that making their home on College Hill naturally invites reflection on where they came from. Share how an aspect of your growing up has inspired or challenged you, and what unique contributions this might allow you to make to the Brown community. (200-250 words)”

A close reading of this prompt shows that Brown puts particular emphasis on place. They do this by using the words “home,” “College Hill,” and “where they came from.” Thus, Brown invites writers to think about community through the prism of place. They also emphasize the idea of personal growth or change, through the words “inspired or challenged you.” Therefore, Brown wishes to see how the place you grew up in has affected you. And, they want to know how you in turn will affect their college community.

“NYU was founded on the belief that a student’s identity should not dictate the ability for them to access higher education. That sense of opportunity for all students, of all backgrounds, remains a part of who we are today and a critical part of what makes us a world-class university. Our community embraces diversity, in all its forms, as a cornerstone of the NYU experience.

We would like to better understand how your experiences would help us to shape and grow our diverse community. Please respond in 250 words or less.”

Here, NYU places an emphasis on students’ “identity,” “backgrounds,” and “diversity,” rather than any physical place. (For some students, place may be tied up in those ideas.) Furthermore, while NYU doesn’t ask specifically how identity has changed the essay writer, they do ask about your “experience.” Take this to mean that you can still recount a specific moment, or several moments, that work to portray your particular background. You should also try to link your story with NYU’s values of inclusivity and opportunity.

3) University of Washington

“Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. (300 words max) Tip: Keep in mind that the UW strives to create a community of students richly diverse in cultural backgrounds, experiences, values and viewpoints.”

UW ’s community essay prompt may look the most approachable, for they help define the idea of community. You’ll notice that most of their examples (“families,” “cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood”…) place an emphasis on people. This may clue you in on their desire to see the relationships you’ve made. At the same time, UW uses the words “individual” and “richly diverse.” They, like NYU, wish to see how you fit in and stand out, in order to boost campus diversity.

Writing Your First Community Essay

Begin by picking which community essay you’ll write first. (For practical reasons, you’ll probably want to go with whichever one is due earliest.) Spend time doing a close reading of the prompt, as we’ve done above. Underline key words. Try to interpret exactly what the prompt is asking through these keywords.

Next, brainstorm. I recommend doing this on a blank piece of paper with a pencil. Across the top, make a row of headings. These might be the communities you’re a part of, or the components that make up your identity. Then, jot down descriptive words underneath in each column—whatever comes to you. These words may invoke people and experiences you had with them, feelings, moments of growth, lessons learned, values developed, etc. Now, narrow in on the idea that offers the richest material and that corresponds fully with the prompt.

Lastly, write! You’ll definitely want to describe real moments, in vivid detail. This will keep your essay original, and help you avoid cliché. However, you’ll need to summarize the experience and answer the prompt succinctly, so don’t stray too far into storytelling mode.

How To Adapt Your Community Essay

Once your first essay is complete, you’ll need to adapt it to the other colleges involving community essays on your list. Again, you’ll want to turn to the prompt for a close reading, and recognize what makes this prompt different from the last. For example, let’s say you’ve written your essay for UW about belonging to your swim team, and how the sports dynamics shaped you. Adapting that essay to Brown’s prompt could involve more of a focus on place. You may ask yourself, how was my swim team in Alaska different than the swim teams we competed against in other states?

Once you’ve adapted the content, you’ll also want to adapt the wording to mimic the prompt. For example, let’s say your UW essay states, “Thinking back to my years in the pool…” As you adapt this essay to Brown’s prompt, you may notice that Brown uses the word “reflection.” Therefore, you might change this sentence to “Reflecting back on my years in the pool…” While this change is minute, it cleverly signals to the reader that you’ve paid attention to the prompt, and are giving that school your full attention.

What to Avoid When Writing the Community Essay

- Avoid cliché. Some students worry that their idea is cliché, or worse, that their background or identity is cliché. However, what makes an essay cliché is not the content, but the way the content is conveyed. This is where your voice and your descriptions become essential.

- Avoid giving too many examples. Stick to one community, and one or two anecdotes arising from that community that allow you to answer the prompt fully.

- Don’t exaggerate or twist facts. Sometimes students feel they must make themselves sound more “diverse” than they feel they are. Luckily, diversity is not a feeling. Likewise, diversity does not simply refer to one’s heritage. If the prompt is asking about your identity or background, you can show the originality of your experiences through your actions and your thinking.

Community Essay Examples and Analysis

Brown university community essay example.

I used to hate the NYC subway. I’ve taken it since I was six, going up and down Manhattan, to and from school. By high school, it was a daily nightmare. Spending so much time underground, underneath fluorescent lighting, squashed inside a rickety, rocking train car among strangers, some of whom wanted to talk about conspiracy theories, others who had bedbugs or B.O., or who manspread across two seats, or bickered—it wore me out. The challenge of going anywhere seemed absurd. I dreaded the claustrophobia and disgruntlement.

Yet the subway also inspired my understanding of community. I will never forget the morning I saw a man, several seats away, slide out of his seat and hit the floor. The thump shocked everyone to attention. What we noticed: he appeared drunk, possibly homeless. I was digesting this when a second man got up and, through a sort of awkward embrace, heaved the first man back into his seat. The rest of us had stuck to subway social codes: don’t step out of line. Yet this second man’s silent actions spoke loudly. They said, “I care.”

That day I realized I belong to a group of strangers. What holds us together is our transience, our vulnerabilities, and a willingness to assist. This community is not perfect but one in motion, a perpetual work-in-progress. Now I make it my aim to hold others up. I plan to contribute to the Brown community by helping fellow students and strangers in moments of precariousness.

Brown University Community Essay Example Analysis

Here the student finds an original way to write about where they come from. The subway is not their home, yet it remains integral to ideas of belonging. The student shows how a community can be built between strangers, in their responsibility toward each other. The student succeeds at incorporating key words from the prompt (“challenge,” “inspired” “Brown community,” “contribute”) into their community essay.

UW Community Essay Example

I grew up in Hawaii, a world bound by water and rich in diversity. In school we learned that this sacred land was invaded, first by Captain Cook, then by missionaries, whalers, traders, plantation owners, and the U.S. government. My parents became part of this problematic takeover when they moved here in the 90s. The first community we knew was our church congregation. At the beginning of mass, we shook hands with our neighbors. We held hands again when we sang the Lord’s Prayer. I didn’t realize our church wasn’t “normal” until our diocese was informed that we had to stop dancing hula and singing Hawaiian hymns. The order came from the Pope himself.

Eventually, I lost faith in God and organized institutions. I thought the banning of hula—an ancient and pure form of expression—seemed medieval, ignorant, and unfair, given that the Hawaiian religion had already been stamped out. I felt a lack of community and a distrust for any place in which I might find one. As a postcolonial inhabitant, I could never belong to the Hawaiian culture, no matter how much I valued it. Then, I was shocked to learn that Queen Ka’ahumanu herself had eliminated the Kapu system, a strict code of conduct in which women were inferior to men. Next went the Hawaiian religion. Queen Ka’ahumanu burned all the temples before turning to Christianity, hoping this religion would offer better opportunities for her people.

Community Essay (Continued)

I’m not sure what to make of this history. Should I view Queen Ka’ahumanu as a feminist hero, or another failure in her islands’ tragedy? Nothing is black and white about her story, but she did what she thought was beneficial to her people, regardless of tradition. From her story, I’ve learned to accept complexity. I can disagree with institutionalized religion while still believing in my neighbors. I am a product of this place and their presence. At UW, I plan to add to campus diversity through my experience, knowing that diversity comes with contradictions and complications, all of which should be approached with an open and informed mind.

UW Community Essay Example Analysis

This student also manages to weave in words from the prompt (“family,” “community,” “world,” “product of it,” “add to the diversity,” etc.). Moreover, the student picks one of the examples of community mentioned in the prompt, (namely, a religious group,) and deepens their answer by addressing the complexity inherent in the community they’ve been involved in. While the student displays an inner turmoil about their identity and participation, they find a way to show how they’d contribute to an open-minded campus through their values and intellectual rigor.

What’s Next

For more on supplemental essays and essay writing guides, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the Why This Major Essay + Example

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- How to Start a College Essay – 12 Techniques and Tips

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Sign Up Now

Key Concepts

Learning Communities

Learning communities provide a space and a structure for people to align around a shared goal. Effective communities are both aspirational and practical. They connect people, organizations, and systems that are eager to learn and work across boundaries, all the while holding members accountable to a common agenda, metrics, and outcomes. These communities enable participants to share results and learn from each other, thereby improving their ability to achieve rapid yet significant progress.

There are large, well-researched bodies of knowledge about learning communities, communities of practice and purpose, and collective impact. At the Center, we draw from that expert knowledge and apply it to our innovation approach. We see learning communities as critical components for building distributed leadership and scaling promising practices by connecting organizations, agencies, and philanthropies who both share the community’s goal and have the capability to operate at scale. The features of learning communities most relevant to our work are described below.

What does a learning community do?

Jessica Sager, Co-Founder and Executive Director of All Our Kin, shares the benefits of participating in FOI and its learning community.

- It connects people. Learning communities convene change agents across sectors, disciplines, and geographies to connect, share ideas and results, and learn from each other. Communities may work together in-person and virtually.

- It sets goals and measures collective progress. These communities align participants around common goals, metrics (ways of measuring achievement), theories of change , and areas of practice.

- It enables shared learning. Communities share learning from both successful and unsuccessful experiences to deepen collective knowledge.

- It supports distributed leadership . The scope of a learning community allows it to offer a wide range of leadership roles and skill-building opportunities.

- It accelerates progress toward impact at scale . These communities facilitate fast-cycle learning, measure results to understand what works for whom, and bring together the key stakeholders who can achieve systems-level change.

Why are learning communities important?

Achieving widespread change in the early childhood field requires tackling an interrelated set of complex social problems. To solve these problems, the field needs a strong community of learning and practice that will work to identify multiple intervention strategies for different groups of children and families. Rather than replicate “successful” programs in different contexts — where they may or may not achieve the same results — learning communities share results and metrics to figure out what works best for whom and why. This approach provides a highly targeted and effective way to achieve impact at scale.

View Learning Communities in Action

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write Stanford’s “Excited About Learning” Essay

This article was written based on the information and opinions presented by Johnathan Patin-Sauls and Vinay Bhaskara in a CollegeVine livestream. You can watch the full livestream for more info.

What’s Covered:

Choosing an idea vs. an experience, learning for the sake of learning, learning as a means to other ends, be specific.

Stanford University’s first essay prompt asks you to respond to the following:

“ The Stanford community is deeply curious and driven to learn in and out of the classroom. Reflect on an idea or experience that makes you genuinely excited about learning. (100-250 words)”

For this short answer question, your response is limited to a maximum of 250 words. In this article, we will discuss considerations for choosing to write about an idea or experience, ways to demonstrate a love or enthusiasm for learning, and why you should be as specific. For more information and guidance on writing the application essays for Stanford University, check out our post on how to write the Stanford University essays .

Regardless of if you choose either an idea or experience that makes you genuinely excited about learning as a topic, there are a few considerations for each.

Most people gravitate towards writing about an idea. One challenge that arises with an idea-focused essay is that applicants who are passionate about an idea often become hyper focused on explaining the idea but neglect to connect this idea to who they are as a person and why this idea excites them.

When writing about an experience, it is important to strike a balance between describing the experience and analyzing the impact of the experience on you, your goals, and your commitment to learning.

This essay question allows you to expand on your joy for learning and your genuine curiosity. Stanford is searching for students who are naturally curious and enjoy the process of learning and educating themselves. For example, a compelling essay could begin with a riveting story of getting lost while hiking the Appalachian Trail and describing how this experience led to a lifelong passion for studying primitive forms of navigation.

There is a strong tendency among applicants to write about formal academic coursework, however, the most compelling essays will subvert expectations by taking the concept of learning beyond the classroom and demonstrating how learning manifests itself in unique contexts in your life.

If you’re someone for whom learning is a means to other ends, it is important that you convey a sense of genuine enthusiasm and purpose beyond, “I want to go to X school because it will help me get Y job for Z purpose.” You may be motivated to attend college to obtain a certain position and make a comfortable income, however these answers are not necessarily what admissions officers are looking for. Instead, it can be helpful to relate an idea or experience to something more personal to you.

Academic & Professional Trajectory

Consider relating the idea or experience you choose to a major, degree program, research initiative, or professor that interests you at Stanford. Then go beyond the academic context to explain how the idea or experience ties into your future career.

For instance, if you are interested in the concept of universal health care, then you might describe your interest in applying to public health programs with faculty that specialize in national health care systems. You might then describe your long term career aspirations to work in the United States Senate on crafting and passing health care policy.

Personal Values & Experiences

Another way to tie the ideas in this essay back to a more personal topic is to discuss how the idea or experience informs who you are, how you treat others, or how you experience the world around you.

You could also focus on an idea or experience that has challenged, frustrated, or even offended you, thereby reinforcing and further justifying the values you hold and your worldview.

Community Building & Social Connectedness

You may also explore how this idea or experience connects you to a particular community by helping you understand, build, and support members of the community. Stanford is looking to find students who will be engaged members of the student body and carry out the community’s core mission, values, and projects, so this essay can be an opportunity to highlight how you would contribute to Stanford.

Be specific in your choice of idea or the way in which you describe an experience. For example, a response that focuses on the joys of learning philosophy is too broad to be particularly memorable or impactful. However, the mind-body problem looking at the debate concerning the relationship between thought and consciousness is a specific philosophical idea that lends itself to a rich discussion.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

How Do You Define a Community?

Richard E. West & Gregory S. Williams

Editor’s note: The following article was first published under an open license in Educational Technology Research and Development with the following citation:

West, R. E. & Williams, G. (2018). I don’t think that word means what you think it means: A proposed framework for defining learning communities. Educational Technology Research and Development . Available online at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11423-017-9535-0 .

A strong learning community “sets the ambience for life-giving and uplifting experiences necessary to advance an individual and a whole society” (Lenning and Ebbers 1999 ); thus the learning community has been called “a key feature of 21st century schools” (Watkins 2005 ) and a “powerful educational practice” (Zhao and Kuh 2004 ). Lichtenstein ( 2005 ) documented positive outcomes of student participation in learning communities such as higher retention rates, higher grade point averages, lower risk of academic withdrawal, increased cognitive skills and abilities, and improved ability to adjust to college. Watkins ( 2005 ) pointed to a variety of positive outcomes from emphasizing the development of community in schools and classes, including higher student engagement, greater respect for diversity of all students, higher intrinsic motivation, and increased learning in the areas that are most important. In addition, Zhao and Kuh ( 2004 ) found learning communities associated with enhanced academic performance; integration of academic and social experiences; gains in multiple areas of skill, competence, and knowledge; and overall satisfaction with the college experience.

Because of the substantial learning advantages that research has found for strong learning communities, teachers, administrators, researchers, and instructional designers must understand how to create learning communities that provide these benefits. Researchers and practitioners have overloaded the literature with accounts, studies, models, and theories about how to effectively design learning communities. However, synthesizing and interpreting this scholarship can be difficult because researchers and practitioners use different terminology and frameworks for conceptualizing the nature of learning communities. Consequently, many become confused about what a learning community is or how to measure it.

In this chapter we address ways learning communities can be operationalized more clearly so research is more effective, based on a thorough review of the literature described in our other article (West & Williams, 2017).

Defining learning communities

Knowing what we mean when we use the word community is important for building understanding about best practices. Shen et al. ( 2008 ) concluded, “[H]ow a community of learners forms and how social interaction may foster a sense of community in distance learning is important for building theory about the social nature of online learning” (p. 18). However, there is very little agreement among educational researchers about what the specific definition of a learning community should be. This dilemma is, of course, not unique to the field of education, as rural sociologists have also debated for decades the exact meaning of community as it relates to their work (Clark 1973 ; Day and Murdoch 1993 ; Hillery 1955 ).

In the literature, learning communities can mean a variety of things, which are certainly not limited to face-to-face settings. Some researchers use this term to describe something very narrow and specific, while others use it for broader groups of people interacting in diverse ways, even though they might be dispersed through time and space. Learning communities can be as large as a whole school, or as small as a classroom (Busher 2005 ) or even a subgroup of learners from a larger cohort who work together with a common goal to provide support and collaboration (Davies et al. 2005 ). The concept of community emerges as an ambiguous term in many social science fields.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of researching learning communities is the overwhelming acceptance of a term that is so unclearly defined. Strike ( 2004 ) articulated this dilemma through an analogy: “The idea of community may be like democracy: everyone approves of it, but not everyone means the same thing by it. Beneath the superficial agreement is a vast substratum of disagreement and confusion” (p. 217). When a concept or image is particularly fuzzy, some find it helpful to focus on the edges (boundaries) to identify where “it” begins and where “it” ends, and then work inward to describe the thing more explicitly. We will apply this strategy to learning communities and seek to define a community by its boundaries.

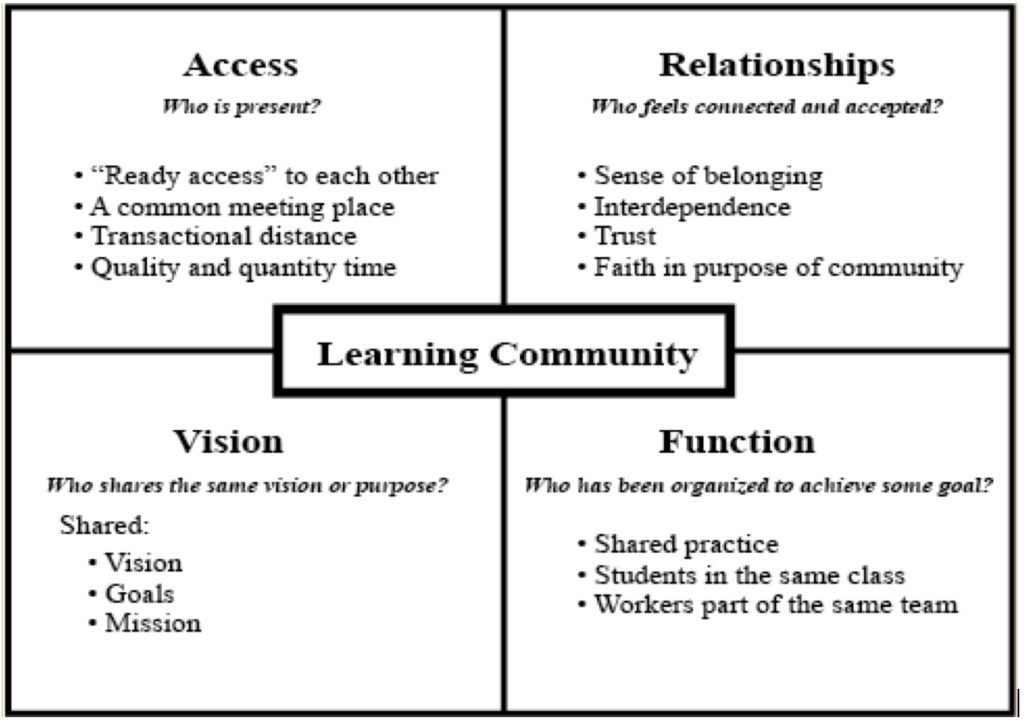

However, researchers have different ideas about what those boundaries are (Glynn 1981 ; Lenning and Ebbers 1999 ; McMillan and Chavis 1986 ; Royal and Rossi 1996 ) and which boundaries are most critical for defining a learning community. In our review of the literature, we found learning community boundaries often defined in terms of participants’ sense that they share access, relationships, vision, or function (see Fig. 1 ). Each of these boundaries contributes in various ways to different theoretical understandings of a learning community.

Community defined by access

Access might have been at one point the easiest way to define a community. If people lived close together, they were a community. If the children attended the same school or classroom, then they were a school or class community. Some researchers and teachers continue to believe that defining a community is that simple (For example, Kay et al., 2011 ).

This perception about spatial/geographic communities is common in community psychology research, but also emerges in education when scholars refer to the “classroom community” as simply a synonym for the group of students sitting together. Often this concept is paired with the idea of a cohort, or students entering programs of professional or educational organizations who form a community because they share the same starting time and the same location as their peers.

However, because of modern educational technologies, the meaning of being “present” or having access to one another in a community is blurred, and other researchers are expanding the concept of what it means to be “present” in a community to include virtual rather than physical opportunities for access to other community members.

Rovai et al. ( 2004 ) summarized general descriptions of what it means to be a community from many different sources (Glynn 1981 ; McMillan 1996 ; Royal and Rossi 1996 ; Sarason 1974 ) and concluded that members of a learning community need to have “ready access” to each other (Rovai et al. 2004 ). He argued that access can be attained without physical presence in the same geographic space. Rovai ( 2002 ) previously wrote that learning communities need a common meeting place, but indicated that this could be a common virtual meeting place. At this common place, members of the community can hold both social and intellectual interactions, both of which are important for fostering community development. One reason why many virtual educational environments do not become full learning communities is that although the intellectual activity occurs in the learning management system, the social interactions may occur in different spaces and environments, such as Twitter and Facebook—thus outside of the potential community.

The negotiation among researchers about what it means to be accessible in a learning community, including whether these boundaries of access are virtual or physical, is still ongoing. Many researchers are adjusting traditional concepts of community boundaries as being physical in order to accommodate modern virtual communities. However, many scholars and practitioners still continue to discuss communities as being bounded by geographic locations and spaces, such as community college math classrooms (Weissman et al. 2011 ), preservice teachers’ professional experiences (Cavanagh and Garvey 2012 ), and music educator PhD cohorts (Shin 2013 ). More important is the question of how significant physical or virtual access truly is. Researchers agree that community members should have access to each other, but the amount of access and the nature of presence needed to qualify as a community are still undefined.

Community defined by relationships

Being engaged in a learning community often requires more than being present either physically or virtually. Often researchers define learning communities by their relational or emotional boundaries: the emotional ties that bind and unify members of the community (Blanchard et al. 2011 ). Frequently a learning community is identified by how close or connected the members feel to each other emotionally and whether they feel they can trust, depend on, share knowledge with, rely on, have fun with, and enjoy high quality relationships with each other (Kensler et al. 2009 ). In this way, affect is an important aspect of determining a learning community. Often administrators or policymakers attempt to force the formation of a community by having the members associate with each other, but the sense of community is not discernible if the members do not build the necessary relational ties. In virtual communities, students may feel present and feel that others are likewise discernibly involved in the community, but still perceive a lack of emotional trust or connection.

In our review of the literature, we found what seem to be common relational characteristics of learning communities: (1) sense of belonging, (2) interdependence or reliance among the members, (3) trust among members, and (4) faith or trust in the shared purpose of the community.

Members of a community need to feel that they belong in the community, which includes feeling like one is similar enough or somehow shares a connection to the others. Sarason ( 1974 ) gave an early argument for the psychological needs of a community, which he defined in part as the absence of a feeling of loneliness. Other researchers have agreed that an essential characteristic of learning communities is that students feel “connected” to each other (Baker and Pomerantz 2000 ) and that a characteristic of ineffective learning communities is that this sense of community is not present (Lichtenstein 2005 ).

Interdependence

Sarason ( 1974 ) believed that belonging to a community could best be described as being part of a “mutually supportive network of relationships upon which one could depend” (p. 1). In other words, the members of the community need each other and feel needed by others within the community; they feel that they belong to a group larger than the individual self. Rovai ( 2002 ) added that members often feel that they have duties and obligations towards other members of the community and that they “matter” or are important to each other.

Some researchers have listed trust as a major characteristic of learning communities (Chen et al. 2007 ; Mayer et al. 1995 ; Rovai et al. 2004 ). Booth’s ( 2012 ) focus on online learning communities is one example of how trust is instrumental to the emotional strength of the learning group. “Research has established that trust is among the key enablers for knowledge sharing in online communities” (Booth 2012 , p. 5). Related to trust is the feeling of being respected and valued within a community, which is often described as essential to a successful learning community (Lichtenstein 2005 ). Other authors describe this feeling of trust or respect as feeling “safe” within the community (Baker and Pomerantz 2000 ). For example, negative or ineffective learning communities have been characterized by conflicts or instructors who were “detached or critical of students and unable or unwilling to help them” (Lichtenstein 2005 , p. 348).

Shared faith

Part of belonging to a community is believing in the community as a whole—that the community should exist and will be sufficient to meet the members’ individual needs. McMillan and Chavis ( 1986 ) felt that it was important that there be “a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together” (p. 9). Rovai et al. ( 2004 ) agreed by saying that members “possess a shared faith that their educational needs will be met through their commitment to the shared goals and values of other students at the school” (p. 267).

These emotional boundaries not only define face-to-face learning communities, but they define virtual communities as well—perhaps more so. Because virtual communities do not have face-to-face interaction, the emotional bond that members feel with the persons beyond the computer screen may be even more important, and the emergence of video technologies is one method for increasing these bonds (Borup et al. 2014 ).

Community defined by vision

Communities defined by shared vision or sense of purpose are not as frequently discussed as boundaries based on relationships, but ways members of a community think about their group are important. Rather than feeling like a member of a community—with a sense of belonging, shared faith, trust, and interdependence—people can define community by thinking they are a community. They conceptualize the same vision for what the community is about, share the same mission statements and goals, and believe they are progressing as a community towards the same end. In short, in terms many researchers use, they have a shared purpose based on concepts that define the boundaries of the community. Sharing a purpose is slightly different from the affective concept of sharing faith in the existence of the community and its ability to meet members’ needs. Community members may conceptualize a vision for their community and yet not have any faith that the community is useful (e.g., a member of a math community who hates math). Members may also disagree on whether the community is capable of reaching the goal even though they may agree on what the goal is (“my well intentioned study group is dysfunctional”). Thus conceptual boundaries of a community of learners are distinct from relational ties; they simply define ways members perceive the community’s vision. Occasionally the shared conception is the most salient or distinguishing characteristic of a particular learning community.

Schrum et al. ( 2005 ) summarized this characteristic of learning communities by saying that a community is “individuals who share common purposes related to education” (p. 282). Royal and Rossi ( 1996 ) also described effective learning communities as rich environments for teamwork among those with a common vision for the future of their school and a common sense of purpose.

Community defined by function

Perhaps the most basic way to define the boundaries of a learning community is by what the members do. For example, a community of practice in a business would include business participants engaged in that work. This type of definition is often used in education which considers students members of communities simply because they are doing the same assignments: Participants’ associations are merely functional, and like work of research teams organized to achieve a particular goal, they hold together as long as the work is held in common. When the project is completed, these communities often disappear unless ties related to relationships, conceptions, or physical or virtual presence [access] continue to bind the members together.

The difference between functional boundaries and conceptual boundaries [boundaries of function and boundaries of vision or purpose] may be difficult to discern. These boundaries are often present simultaneously, but a functional community can exist in which the members work on similar projects but do not share the same vision or mental focus about the community’s purpose. Conversely, a group of people can have a shared vision and goals but be unable to actually work together towards this end (for example, if they are assigned to different work teams). Members of a functional community may work together without the emotional connections of a relational community, and members who are present in a community may occupy the same physical or virtual spaces but without working together on the same projects. For example, in co-working spaces, such as Open Gov Hub in Washington D.C., different companies share an open working space, creating in a physical sense a very real community, but members of these separate companies would not be considered a community according to functional boundaries. Thus all the proposed community boundaries sometimes overlap but often represent distinctive features.

The importance of functional cohesion in a learning community is one reason why freshman learning communities at universities usually place cohorts of students in the same classes so they are working on the same projects. Considering work settings, Hakkarainen et al. ( 2004 ) argued that the new information age in our society requires workers to be capable of quickly forming collaborative teams (or networked communities of expertise) to achieve a particular functional purpose and then be able to disband when the project is over and form new teams. They argued that these networked communities are increasingly necessary to accomplish work in the 21st Century.

Relying on functional boundaries to define a learning community is particularly useful with online communities. A distributed and asynchronously meeting group can still work on the same project and perhaps feel a shared purpose along with a shared functional assignment, sometimes despite not sharing much online social presence or interpersonal attachment.

Many scholars and practitioners agree that learning communities “set the ambience for life-giving and uplifting experiences necessary to advance an individual and a whole society” (Lenning and Ebbers 1999 ). Because learning communities are so important to student learning and satisfaction, clear definitions that enable sharing of best practices are essential. By clarifying our understanding and expectations about what we hope students will be able to do, learn, and become in a learning community, we can more precisely identify what our ideal learning community would be like and distinguish this ideal from the less effective/efficient communities existing in everyday life and learning.

In this chapter we have discussed definitions for four potential boundaries of a learning community. Two of these can be observed externally: access (Who is present physically or virtually?) and function (Who has been organized specifically to achieve some goal?). Two of these potential boundaries are internal to the individuals involved and can only be researched by helping participants describe their feelings and thoughts about the community: relationships (Who feels connected and accepted?) and vision (who shares the same mission or purpose?).

Researchers have discussed learning communities according to each of these four boundaries, and often a particular learning community can be defined by more than one. By understanding more precisely what we mean when we describe a group of people as a learning community—whether we mean that they share the same goals, are assigned to work/learn together, or simply happen to be in the same class—we can better orient our research on the outcomes of learning communities by accounting for how we erected boundaries and defined the subjects. We can also develop better guidelines for cultivating learning communities by communicating more effectively what kinds of learning communities we are trying to develop.

Application Exercises

- Evaluate your current learning community. How can you strengthen your personal learning community? Make one commitment to accomplish this goal.

- Analyze an online group (Facebook users, Twitter users, NPR readers, Pinners on Pinterest, etc.) that you are part of to determine if it would fit within the four proposed boundaries of a community. Do you feel like an active member of this community? Why or why not?

Baker, S., & Pomerantz, N. (2000). Impact of learning communities on retention at a metropolitan university. Journal of College Student Retention, 2(2), 115–126. CrossRef Google Scholar

Blanchard, A. L., Welbourne, J. L., & Boughton, M. D. (2011). A model of online trust. Information, Communication & Society, 14(1), 76–106. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8502 . CrossRef Google Scholar

Booth, S. E. (2012). Cultivating knowledge sharing and trust in online communities for educators. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 47(1), 1–31. CrossRef Google Scholar

Borup, J., West, R., Thomas, R., & Graham, C. (2014). Examining the impact of video feedback on instructor social presence in blended courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1821 .

Busher, H. (2005). The project of the other: Developing inclusive learning communities in schools. Oxford Review of Education, 31(4), 459–477. doi: 10.1080/03054980500222221 . CrossRef Google Scholar

Cavanagh, M. S., & Garvey, T. (2012). A professional experience learning community for pre-service secondary mathematics teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(12), 57–75. CrossRef Google Scholar

Chen, Y., Yang, J., Lin, Y., & Huang, J. (2007). Enhancing virtual learning communities by finding quality learning content and trustworthy collaborators. Educational Technology and Society, 10(2), 1465–1471. Retrieved from http://dspace.lib.fcu.edu.tw/handle/2377/3722 .

Clark, D. B. (1973). The concept of community: A re-examination. The Sociological Review, 21,397–416. CrossRef Google Scholar

Davies, A., Ramsay, J., Lindfield, H., & Couperthwaite, J. (2005). Building learning communities: Foundations for good practice. British Journal of Educational Technology,36(4), 615–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00539.x . CrossRef Google Scholar

Day, G., & Murdoch, J. (1993). Locality and community: Coming to terms with place. The Sociological Review, 41, 82–111. CrossRef Google Scholar

Glynn, T. (1981). Psychological sense of community: Measurement and application. Human Relations, 34(7), 789–818. CrossRef Google Scholar

Hakkarainen, K., Palonen, T., Paavola, S., & Lehtinen, E. (2004). Communities of networked expertise: Professional and educational perspectives. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. Google Scholar

Hillery, G. A. (1955). Definitions of community: Areas of agreement. Rural Sociology, 20, 111–123. Google Scholar

Kay, D., Summers, J., & Svinicki, M. (2011). Conceptualizations of classroom community in higher education: Insights from award winning professors. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 5(4), 230–245. Google Scholar

Kensler, L. A. W., Caskie, G. I. L., Barber, M. E., & White, G. P. (2009). The ecology of democratic learning communities: Faculty trust and continuous learning in public middle schools. Journal of School Leadership, 19, 697–735. Google Scholar

Lenning, O. T., & Ebbers, L. H. (1999). The powerful potential of learning communities: Improving education for the future, Vol. 16, No. 6. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report. Google Scholar

Lichtenstein, M. (2005). The importance of classroom environments in the assessment of learning community outcomes. Journal of College Student Development, 46(4), 341–356. CrossRef Google Scholar

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integration model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.24348410 . Google Scholar

McMillan, D. W. (1996). Sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 315–325. CrossRef Google Scholar

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23. CrossRef Google Scholar

Rovai, A. P. (2002). Development of an instrument to measure classroom community. Internet & Higher Education, 5(3), 197. CrossRef Google Scholar

Rovai, A. P., Wighting, M. J., & Lucking, R. (2004). The classroom and school community inventory: Development, refinement, and validation of a self-report measure for educational research. Internet & Higher Education, 7(4), 263–280. CrossRef Google Scholar

Royal, M. A., & Rossi, R. J. (1996). Individual-level correlates of sense of community: Findings from workplace and school. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 395–416. CrossRef Google Scholar

Sarason, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Google Scholar

Schrum, L., Burbank, M. D., Engle, J., Chambers, J. A., & Glassett, K. F. (2005). Post-secondary educators’ professional development: Investigation of an online approach to enhancing teaching and learning. Internet and Higher Education, 8, 279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2005.08.001 . CrossRef Google Scholar

Shen, D., Nuankhieo, P., Huang, X., Amelung, C., & Laffey, J. (2008). Using social network analysis to understand sense of community in an online learning environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 39(1), 17–36. doi: 10.2190/EC.39.1.b . CrossRef Google Scholar

Shin, J. (2013). A community of peer interactions as a resource to prepare music teacher educators. Research and Issues In Music Education, 11(1). Retrieved from http://www.stthomas.edu/rimeonline/vol11/shin.htm .

Strike, K. A. (2004). Community, the missing element of school reform: Why schools should be more like congregations than banks. American Journal of Education, 110(3), 215–232. doi: 10.1086/383072 . CrossRef Google Scholar

Watkins, C. (2005). Classrooms as learning communities: A review of research. London Review of Education, 3(1), 47–64. CrossRef Google Scholar

Weissman, E., Butcher, K. F., Schneider, E., Teres, J., Collado, H., & Greenberg, D. (2011). Learning communities for students in developmental math: Impact studies at Queensborough and Houston Community Colleges. National Center for Postsecondary Research. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1782120 .

Zhao, C.-M., & Kuh, G. D. (2004). Adding value: Learning communities and student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45(2), 115–138. doi: 10.1023/B:RIHE.0000015692.88534.de . CrossRef Google Scholar

Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology Copyright © 2018 by Richard E. West & Gregory S. Williams is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities Essay

Introduction, the importance of virtual learning communities, challenges of building a virtual learning community.

Virtual learning communities are those “based on shared purpose rather than actual geographical location” (Lewis & Allan, 2004). The learners from different parts of the world are drawn together and they can form their learning groups formally or informally. This is facilitated by appropriate information and communication technologies such as the internet and video conferencing (Lewis & Allan, 2004).

Since virtual learning communities are based on real-time communication, the learners can be taught at the same time by a single instructor. Consequently, most online degree programs focus on building virtual learning communities to enhance their teaching and students’ learning process. This paper seeks to analyze the importance of virtual learning communities in an online degree program. The challenges likely to be faced while building such communities will be illuminated.

Initial Cohort Seminars

Most online degree programs have an initial course that focuses on introducing the students to the online learning process. Such courses facilitate the building of social relationships among the students. Through such relationships, the online instructor and the students can easily explore both social and academic challenges faced by distance students (Assaf, Elisa, & Fayyuoum, 2009).

To build strong relationships between the instructors and the students at the beginning of the program, they must interact for a long period. This means that the normal online class time needs to be extended through a system that facilitates a seamless exchange of information among the students and their instructors. This objective is best achieved through a virtual learning community that promotes unlimited exchange of ideas among the stakeholders in the learning process (Assaf, Elisa, & Fayyuoum, 2009). This is because the students can integrate their office hours with the learning process thus enabling them to access more information.

Continuous Mentor Involvement

According to the behaviorism theory, learning is enhanced if students can follow and master the facts or skills taught by the instructors (Lewis & Allan, 2004). This means that the instructor must be constantly in touch with his or her students to impart knowledge effectively. The virtual learning communities enable instructors in online degree programs to share knowledge with the students as well as get frequent feedback from them (Brown, 2001).

This helps in assessing the students’ progress as well as recommending timely remedies for the underperformers. In addition to this, the virtual learning communities enable the online degree programs to provide a student mentor. The mentor, through the virtual learning community, works closely with the learners throughout the program (Brown, 2001). Through the mentorship programs, students can acquire skills that enable them to overcome the challenges they face in learning. The motivations accruing from the mentorship programs thus facilitates a high completion rate.

Content-Based Learning

According to the constructivist theory, students learn new ideas through active interactions with their peers (Lewis & Allan, 2004). The virtual learning communities bring together students and instructors from different walks of life. Consequently, the students can share their diverse experiences, ideas, and skills seamlessly. The learning communities enable the instructors and the students to volunteer their questions (McEliath & McDowell, 2008).

The questions and their proposed answers are normally challenged by different students. This not only enhances a better understanding of the question or the topic under discussion but also facilitates the discovery of new ideas. Besides, the insights on the question or topic under discussion will be readily available to all the students using the learning community. Thus each participant will expand his or her critical thinking as they acknowledge diverse perspectives. This will enable them to “construct a fuller understanding of the topic of investigation” (McEliath & McDowell, 2008).

Instructor’s Role in Learning

Most online degree programs are characterized by an e-moderator who presents the course content to the students. In most cases, the e-moderator dominates the video conferences used to impart knowledge. In such a case, the students play a passive role in the learning process. However, this strategy of teaching is less effective since the students tend to lose interest in the course as they lose control over the learning process. To avoid this problem, the role of the e-moderator should shift from addressing the technical or social concerns of the students to facilitating the learning process.

This means that the moderator’s task should be limited to facilitating “exchange of information, knowledge processing as well as practical processing” (Vesely & Bloom, 2007). This can only be achieved if the moderator’s authority and control over the learning process is progressively shifted to the students. The students should have greater autonomy over the learning process to encourage active participation and better results. The virtual learning communities enable online degree programs to give students autonomy over the learning process (Vesely & Bloom, 2007). The students set the pace that suits their abilities while the e-moderator clarifies communication and encourage diverse perspectives from students.

Organization of Resources

Under normal circumstances, students usually categorize and organize online resources in different ways. Their diverse organization process is meant to suit their specific searching habits and conveniences (Williams & Humphrey, 2007). However, the lack of a standard method for organizing online resources makes it difficult to access such resources. Thus the online resources will not be of any value if they can not be accessed by the majority of the students and this leads to poor quality education.

In response to this challenge, many online degree programs embark on the use of virtual learning communities to distribute the learning materials as well as enabling students to share their learning materials effectively (Williams & Humphrey, 2007). The virtual learning communities not only use standard methods of accessing information but also have a dedicated support team that assists students to access the needed materials.

Despite the benefits of a virtual learning community to an online degree program, building it is often characterized by several challenges. Some of the challenges experienced by online degree programs in their attempt to build an effective virtual learning community include the following.

Communication Barriers

Since most students enrolled in online degree programs are from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds, they tend to speak different languages. Most online degree programs use English as the official instructional language even though not all students are proficient in English. Lack of a good command of the language used in the virtual learning community can limit the students’ ability to share information with their peers as well as their instructors (Fontainha, 2008). Besides, the intended meaning of a text may change due to the improper use of language.

This presents a great difficulty in the learning process since information will not be shared seamlessly. Attempts to solve this problem through the translation capabilities of the internet have yielded little results since the internet can only translate English into a limited number of languages (Fontainha, 2008). In some cases, students with poor listening and writing skills have failed to benefit from the virtual learning communities by misinterpreting information. Thus presenting information in a manner that is highly understandable given the communication capabilities of the students is the main challenge in building a virtual learning community.

Diverse Technical Backgrounds

Users of virtual learning communities have diverse technological backgrounds. The students’ ability to use modern information and communication technologies depends on their prior exposure to such technologies in their countries of origin (Vesely & Bloom, 2007). However, due to disparities in economic development and technological advancements across the globe, some students have a richer technological background as compare to their colleagues. The consequence of this technological imbalance is that students with little exposure to modern communication technologies will not benefit from the virtual learning communities (Brown, 2001).

The greatest challenge thus is to develop a virtual learning community that takes into account the diverse technological background of its users. This has been difficult as most learning communities embark on modern and sophisticated technologies to enhance efficiency. Thus students who are not able to use the learning community due to their poor skills will have to invest in further training. However, such training further increases the cost of the online degree hence lowering its demand. From a learning perspective, the inability to use the virtual learning community will lead to poor learning outcomes (McEliath & McDowell, 2008). This is because the students will not be able to fully access all the needed information.

Technological Constraints

Due to disparities in financial status and technological advancement, students from various parts of the world use diverse equipment to access virtual learning systems (Fontainha, 2008). For example, students who use a fast internet based on optical cable technology will benefit more from the virtual learning community as compared to those who use outdated technologies. The computer operating systems used by the students might also not be compatible with the technology that supports the virtual learning community system. Thus the main challenge is developing a learning community software package that is compatible with a variety of both hardware and software packages. This has discouraged most online degree programs from using the learning communities.

Social Challenges

These include varying levels of understanding and the intentions of the users. Students have different levels of understanding. Consequently, some of them can not understand the course content if they do not get personalized instructions (McEliath & McDowell, 2008). Providing personalized instructions has always been difficult since most instructors focus on the “learning community as an entity rather than individuals” (Brown, 2001). Varying intentions of using the learning communities also limits the students’ ability to share information.

The above discussion indicates that a virtual learning community is a system that brings together learners from diverse backgrounds (Lewis & Allan, 2004). Most online degree programs have adopted it to enhance learning. Its main benefit is facilitating the seamless sharing of information and networking among students. However, implementation has been difficult due to the reasons discussed above. Thus to overcome the above challenges, the system should be flexible enough to accommodate the communication and learning needs of the students. Besides, real-time support should be available to enhance usage.

Assaf, W., Elisa, G., & Fayyuoum, A. (2009). Virtual eBMS: a virtual learning community supporting personalized learning. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 5(2) , 238-254.

Brown, E. (2001). The process of community-building in distance learning classes. Journal of Asynchronous Learning,5(1) , 18-35.

Fontainha, E. (2008). Communities of practise and virtual learning communications: benefits, barriers and success factors. Journal of Online Teaching and Learning, 3(2) , 120-130.

Lewis, D., & Allan, B. (2004). Virtual learning communities: a guide for practitioners. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McEliath, E., & McDowell, K. (2008). Pedagogical strategies for building community in graduate level distance education courses. Journal of Online Teaching and Learning, 4(1) , 117-127.

Vesely, P., & Bloom, L. (2007). Key Elemnts of building online community: comparing faculty and student perceptions. Journal of Online Learning and teaching, 3(1) , 234-246.

Williams, R., & Humphrey, R. (2007). Understanding and fostering interactions in threaded discussions. Journal of Asynchronous Learning, 11(1) , 129-143.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 20). The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-virtual-learning-communities/

"The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities." IvyPanda , 20 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-virtual-learning-communities/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities'. 20 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities." January 20, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-virtual-learning-communities/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities." January 20, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-virtual-learning-communities/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Importance of Virtual Learning Communities." January 20, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-importance-of-virtual-learning-communities/.

- Conference Panelist's, Coordinator's, Moderator's Roles

- Mediators and Moderators: Understanding and Using

- Business Information System

- The Importance of Trust in AI Adoption

- Focus Group Method in Research Process

- Discord Server as Online Public Space

- Webinars in Education

- Constituting a New Sales Team

- The Roles of Jury Trial

- Methods of Conducting Exploratory Marketing Research

- Designing and Validating Technological Interventions

- Online Teaching for the Disabled

- Digital Gaming in the Classroom: Teacher’s View

- Literacy Through iPads in Early Education

- New Media Technologies for Teachers

- Skip to main content

- Skip to search

- Skip to footer

Center for Engaged Learning

Learning communities.

Learning communities emphasize collaborative partnerships between students, faculty, and staff, and attempt to restructure the university curriculum to address structural barriers to educational excellence.

In their 1990 publication Learning Communities: Creating Connections Among Students, Faculty, and Disciplines, Faith Gabelnick, Jean MacGregor, Roberta S. Matthews, and Barbara Leigh Smith describe a learning community as “any one of a variety of curricular structures that link together several existing courses – or actually restructure the curricular material entirely – so that students have opportunities for deeper understanding and integration of the material they are learning, and more interaction with one another and their teachers as fellow participants in the learning enterprise” (1990, p. 19). The authors promote the idea that learning communities can “purposefully restructure the curriculum to link together courses or course work so that students find greater coherence in what they are learning as well as increased intellectual interaction with faculty and fellow students” and that they “can address some of the structural features of the modern university that undermine effective teaching and learning” (1990, p.5). As a necessarily collaborative enterprise, learning communities usually incorporate “collaborative and active approaches to learning, some form of team teaching, and interdisciplinary themes” (Gabelnick, et al., 1990, p. 5).

Nancy Shapiro and Jodi Levine (1999) cite Alexander Astin’s (1985, p. 161) view of learning communities:

Such communities can be organized along curricular lines, common career interests, avocational interests, residential living areas, and so on. These can be used to build a sense of group identity, cohesiveness, and uniqueness; to encourage continuity and the integration of diverse curricular and co-curricular experiences; and to counteract the isolation that many students feel.

They expand on Astin’s definition to assert basic characteristics that learning communities share:

- Organizing students and faculty into smaller groups

- Encouraging integration of the curriculum

- Helping students establish academic and social support networks

- Providing a setting for students to be socialized to the expectations of college

- Bringing faculty together in more meaningful ways

- Focusing faculty and students on learning outcomes

- Providing a setting for community-based delivery of academic support programs

- Offering a critical lens for examining the first-year experience (Shapiro & Levine, 1999, p. 3).

Finally, Lenning et al. (2013) define a learning community as an “intentionally developed community that exists to promote and maximize the individual and shared learning of its members. There is ongoing interaction, interplay, and collaboration among the community’s members as they strive for specified common learning goals” (Lenning, et al., 2013, p. 7).

More broadly, Kuh (1996) describes any educationally purposeful activity , such as learning communities, as “undergraduate activities, events, and experiences that are congruent with the institution’s educational purposes and a student’s own educational aspirations.” In a later study he and his co-author describe a learning community as “a formal program where groups of students take two or more classes together, [that] may or may not have a residential component” (Zhao and Kuh, 2004, p. 119). They cite four generic forms of learning communities: curricular, classroom, residential, and student-type (p. 116).

In the 2008 publication High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter, George Kuh states the key goals for learning communities are “to encourage integration of learning across courses, and to involve students with ‘big questions’ that matter beyond the classroom. Students take two or more linked courses as a group and work closely with one another and with their professors. Many learning communities explore a common topic and/or common readings through the lens of different disciplines. Some intentionally link ‘liberal arts’ and ‘professional courses’; others feature service learning” (p. 10).

Back to Top

What makes it a high-impact practice?

High-impact educational activities, such as learning communities, share common characteristics that make them especially effective with students . In Adding Value: Learning Communities and Student Engagement , Chun-Mei Zhao and George D. Kuh (2004, p. 124) enumerate the benefits of participating in learning communities in particular. Specifically, participating in learning communities is uniformly and positively linked with:

- Student academic performance

- Engagement in educationally fruitful activities (e.g., academic integration, active and collaborative learning, interaction with faculty members)

- Gains associated with college attendance

- Overall satisfaction with the college experience.

Pulling from multiple sources, Lenning and Ebbers (1999, p. 51-52) cite the numerous benefits for college students participating in learning communities. Well-designed learning communities emphasizing collaborative learning result in improved GPAs, and higher retention and satisfaction for undergraduate students. In addition, various studies have verified other significant benefits:

- A lower number of students on academic probation;

- Amount and quality of learning;

- Validation of learning;

- Academic skills;

- Self-esteem;

- Satisfaction with the institution, involvement in college, and educational experiences;

- Increased opportunity to write and speak;

- Greater engagement in learning;

- The ability to meet academic and social needs;

- Greater intellectual richness;

- Intellectual empowerment;

- More complex thinking, a more complex world view, and a greater openness to ideas different from one’s own;

- Increased quality and quantity of learning;

- The ability to bridge academic and social environments; and

- Improved involvement and connectedness within the social and academic realms.

Research-Informed Practices

In looking at high-impact educationally purposeful activities, Kuh (2008, p. 19-20) strongly recommends that institutions “make it possible for every student to participate in at least two high-impact activities during his or her undergraduate program, one in the first year, and one taken later in relation to the major field. The obvious choices for incoming students are first-year seminars, learning communities, and service learning… Ideally, institutions would structure the curriculum and other learning opportunities so that one high-impact activity is available to every student every year” (Kuh, 2008, p. 19-20).

Schroeder and Mable (1994, p. 183) offer six specific principles or themes that should be incorporated in the development of learning communities. Themes one through three are characteristic of both residential-group communities and learning communities. Themes four through six apply only to residential learning communities.

- Learning communities are generally small, unique, and cohesive units characterized by a common sense of purpose and powerful peer influences.

- Student interaction within learning communities should be characterized by the four I’s – involvement, investment, influence, and identity.

- Learning communities involve bounded territory that provides easy access to and control of group space that supports ongoing interaction and social stability.

- Learning communities should be primarily student centered, not staff centered, if they are to promote student learning. Staff must assume that students are capable and responsible young adults who are primarily responsible for the quality and extent of their learning.

- Effective learning communities should be the result of collaborative partnerships between faculty, students, and residence hall staff. Learning communities should not be created in a vacuum; they are designed to intentionally achieve specific educational outcomes.

- Learning communities should exhibit a clear set of values and normative expectations for active participation. The normative peer cultures of learning communities enhance student learning and development in specific ways.

Gabelnick, et al. (1990, p. 51) also offers guidelines for how to create learning communities that achieve the best possible results for learners:

- Broad support from both faculty and staff is essential — collaboration must be present from the inception of the learning community development process.

- Stable leadership and an administrative “home” will ensure a greater chance for long-term stability and success.

- Selection of an appropriate design and theme to appeal to students’ academic and personal goals is important. Learning communities should utilize required general courses or pre-major courses, such as pre-law, pre-health, and pre-engineering.

- Choose a faculty team with complementary skills and roles.

- Properly manage enrollment expectations and faculty load.

- Develop effective strategies for recruitment, marketing, and registration.

- Ensure appropriate funding, space, and teaching resources.

Golde & Pribbenow (2000) investigated the experiences of faculty members in residential learning communities, from which they formulated recommendations for navigating the sometimes dicey waters that separate faculty from administrative staff. Some of their recommendations included:

- Faculty hold a deep concern for undergraduate education, and wish to know students better. However, some were surprised about the desire of students to be more personal than faculty had expected (p. 32, 36).

- Faculty were enticed by the idea of participating in interdisciplinary and innovative education (p. 32).

- They were also both excited and concerned with being accepted into the learning community, both by students and veteran faculty members (p. 32, 33)

Some barriers to faculty participation in learning communities included familiar challenges:

- Time — faculty reward system must be addressed and taken into account when expecting faculty participation in learning communities (p. 32)

- Faculty had little awareness of, and in some cases little respect for, the work of student affairs professionals on their campus. Similarly, student affairs staff held a limited view of how faculty might contribute in a residential setting (p. 35).

Golde and Pribbenow conclude that faculty are the best recruiters of other faculty into learning community participation, and that it is important to both include faculty in planning efforts, but also to give them well-defined roles within the community (p. 37-38).

The National Resource Center for Learning Communities website , hosted by the Washington Center at The Evergreen State College, identifies three essential components of effective learning communities :

- “A strategically-defined cohort of students taking courses together which have been identified through a review of institutional data

- “Robust, collaborative partnerships between academic affairs and student affairs

- “Explicitly designed opportunities to practice integrative and interdisciplinary learning”

The National Resource Center also emphasizes that learning communities should be designed with attention to an institution’s unique goals and priorities.

Embedded and Emerging Questions for Research, Practice, and Theory

In their exhaustive review of previous learning community assessment studies, Learning Community Research and Assessment: What We Know Now , Taylor et al. (2003) indicated four key future directions for learning community research and assessment:

- Identifying and assessing a broader scope of learning community outcomes – for students, faculty, and institutions;

- Exploring the specific pedagogical and structural characteristics that lead to positive outcomes;

- Pursuing longitudinal inquiry to examine the long-term impact of learning communities – for students, faculty, and institutions; and

- Improving presentations and publications about learning community research. Taylor et al. (2003, pp. 65-66) note that studies should describe the learning communities program, its institutional context, and its participants; identify inquiry questions and methods; clearly communicate results and corresponding recommendations; exhibit critical self-reflection; and be accessible to readers.

Lenning & Ebbers (1999, p. 88) offer ideas about further areas of study, given that evidence at the time suggested some learning communities are more effective than others, but existing studies were not clear cut in their evidence and were not intended as comparative studies:

- Which student learning communities and combinations thereof are most effective?

- How do we optimize the performance and effectiveness of student learning communities of different kinds?

- How do we motivate faculty to participate fully in student learning communities?

- What do we know about the characteristics of students who do not participate, and how to motivate them?