- Notebooking

Cubism Art Project for Kids

- Famous Artists , Oil Pastel Tutorial

If you are searching for unique art projects for your student(s), we’ve got a creative cubism art project for kids! Don’t let the art term fool you into thinking it’s hard! With our easy step by step instructions along with video tutorial, it’s well worth the time.

What is Cubism Art?

What is cubism art? The cubism style of painting was developed in the early 1900’s. Many artists put together a variety of objects or figures, which resulted in paintings appearing fragmented and abstracted. You may have heard of some of these famous artists including Pablo Picasso and George Braque.

Why is it called Cubism?

The cubism term was used and seemed appropriate due to the objects in the art — they looked like cubes or geometrical shapes.

Whether you are looking for oil pastel art for kids or geometric art type projects, this activity is perfect for introducing the beautiful creations of art.

Cubism Art Project Materials

- Giraffe Cubism Art Template

- Pastel Crayons

- Black Cardstock or Construction Paper

Giraffe Cubism Art Instructions

- Print out Cubism Art with Giraffe Blank Template .

- Using a ruler, draw several diagonal lines across the template. See video for visual.

3. Beginning with the top, begin to outline the ears with an orange pastel crayon.

4. Using a Q-Tip, fill in the remaining white space with the chosen pastel color.

5. Continue to follow the pattern shown on video to determine appropriate colors for each section of the giraffe.

6. Using various shades of yellow, red, brown, green, blue and purple, continue to use the correct pastel colors along with outlining and filling in remaining white space with Q-Tips.

7. Work your way down the art canvas until complete.

8. Getting close to the end! Grab a light green and dark green pastel to wrap up the gorgeous Cubism creation.

9. As you wrap up and finish the pastel colors, glue it onto black cardstock paper or construction paper to display or give as a gift!

Share this post

Valerie Mcclintick

Comments (3)

Hi there! I just came across this giraffe cubism project and it looks so great! I don’t see a link to the video though, and when I searched on youtube it did not show up. Has it been removed? Thanks

where is the video for this? there is no link on this page?

HI I was just wondering if there was a video for this project as it is referred to a number of time but there is no video links on the page???

I have searched online as well and tried to find it on your channel but I’ve had no luck???

Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Arts and Entertainment

How to Do a Cubist Style Painting

Last Updated: December 12, 2023 Approved

This article was co-authored by Kelly Medford . Kelly Medford is an American painter based in Rome, Italy. She studied classical painting, drawing and printmaking both in the U.S. and in Italy. She works primarily en plein air on the streets of Rome, and also travels for private international collectors on commission. She founded Sketching Rome Tours in 2012 where she teaches sketchbook journaling to visitors of Rome. Kelly is a graduate of the Florence Academy of Art. There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 14 testimonials and 83% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 268,902 times.

Cubism is a style of painting that originated with Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso between 1907 and 1914. [1] X Research source The Cubist style sought to show the two-dimensional nature of the canvas. Cubist artists fractured their objects into geometric forms and used multiple and contrasting perspectives in a single painting. It was called Cubism when Louis Vauxcelles, a French art critic, called the forms in Braque’s work “cubes.” Creating your own Cubist style painting can be a fun way to connect with art history and look at painting with a fresh perspective.

Preparing to Paint Your Cubist Art

- Lay down newspaper in your work area to keep it clean.

- Use a glass of water and a soft rag to clean your paintbrushes between colors.

- If you just want to practice, you can also create paintings on large multi-media art paper.

- Your local art supply store should carry paper and canvas.

- You can use any type of paint to achieve a Cubist style, but acrylic works well, especially for beginners. Acrylic paints are versatile, often less expensive than oil paints, and make it easier to create crisp lines. [3] X Research source

- Pick paintbrushes that are labeled for acrylic paints. Get a few different sizes for versatility while you paint.

- Make sure you have a pencil and gum eraser on hand to sketch before you begin to paint.

- You may also need a ruler or yardstick to help guide your lines and make them crisp and straight.

- Decide whether you want to paint a human figure, a landscape, or a still life.

- Choose something that you can look at and study in real life while you are painting. For example, if you want to do a figure, see if a friend can pose for you. If you’d like to paint a still life, arrange a group of objects or an object, like a musical instrument, in front of you.

- Once you have a general sketch, use your ruler to sharpen the edges.

- In any place you’ve sketched soft, rounded lines, go back over them and change them into sharp lines and edges.

- For example, if you’re sketching a person, you might go over the rounded line of the shoulder and make it look more like the top of a rectangle.

Putting Your Idea on Canvas

- Look at the light. Instead of shading and blending, in Cubism, you will use the light to create shapes. Outline, in geometric shapes, where the light falls in your painting.

- Also, use geometric lines to show where you would generally shade in a painting.

- Don’t be afraid to overlap your lines.

- If you want to use bright colors, choose to use between one and three main bright colors so that your painting retains its striking geometry.

- You can also use a monochromatic palette in a single color family. For example, Picasso did many paintings mainly in shades of blue.

- Put your paints onto your palette or a paper plate in front of you. Use white to make shades lighter. Mix the colors that you want.

- With acrylic paints, you can layer colors to make your paintings feel more dimensional.

- If you need to do so, use your ruler to guide your paintbrush, like you did your pencil. You want your paint lines to be just as crisp as your pencil lines.

Making a Cubist Painting for Kids

- Washable acrylic paints work well for painting with kids. You can also create a “painting” masterpiece with markers, crayons, or colored pencils.

- Choose a large sheet of art paper or a notebook of paper to make your Cubist style painting.

- You’ll also need paintbrushes, and a pencil and eraser.

Kelly Medford

Cubist paintings are a great way to stretch your kids' artistic imaginations. Kelly Medford, a plein air painter, says: “With kids, you want to encourage them with whatever they make, give them the skills to keep developing, and always challenge them. Teaching them new skills can help them to refine what they already know.”

- Choose something you have on hand. You want to practice drawing from life instead of just drawing from your imagination.

- Practice making small sketches of your subject in a sketchbook. You want to decide exactly how you will draw it for your final painting.

- As you are sketching, remember that your drawing doesn’t have to be completely realistic.

- It’s okay to overlap lines and exaggerate features. You’re just going to make it even more abstract.

- You don’t want large areas of blank space in your drawing.

- You also don’t want to create too many areas with a bunch of tiny geometric shapes.

- Use black or brown paint to create thin outlines around the shapes you made.

- Try to stick to using only a few different colors.

- These paintings make great decorations for children’s bedrooms.

- They are also good gifts for Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, or Grandparents’ Day.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cube/hd_cube.htm

- ↑ http://www.parkablogs.com/content/choosing-right-canvas-your-paintings-and-artworks

- ↑ http://willkempartschool.com/what-is-the-difference-between-oils-vs-acrylic-paints/

- ↑ https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/cubism

- ↑ http://www.pablopicasso.org/cubism.jsp

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1997.149.12/

- ↑ http://www.craftsy.com/blog/2015/07/acrylic-painting-techniques-for-beginners/

- ↑ http://emptyeasel.com/2007/10/17/what-is-cubism-an-introduction-to-the-cubist-art-movement-and-cubist-painters/

- ↑ http://artfulparent.com/2014/01/our-25-favorite-kids-art-materials.html

- ↑ http://www.theartabet.com/what-should-you-teach-a-young-child-to-draw-ages-3-to-7/

About This Article

To do a Cubist style painting, begin by choosing a subject that appeals to you. Some possibilities include a still life with flowers or a self-portrait—although Cubism is an abstract style, most Cubist painters work from life. Once you’ve decided what to paint, sketch it on the canvas in pencil. Then, look for ways to break the shapes down into more basic geometric forms. Finally, settle on a color palette for your painting—anything from shades of blue to an entire rainbow—and begin filling in the shapes you’ve created with paint. For more beginner-friendly tips, such as how to do Cubist paintings if you’re a kid, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jessika Lashatt

Jan 5, 2022

Did this article help you?

Matthew Harley

Mar 8, 2017

Sandra Millar

Sep 19, 2017

Sydney McArthur

Apr 13, 2020

Samuel Marchildon

May 9, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Easy Cubism Art Project

Cubism is one of my favorite art genres to teach. Because of the influences of contemporary artists (think Romero Britto), children are familiar with how artists transforms everyday objects into geometric shapes, which is a huge hit with this easy cubism art project.

The earlier influences of cubism (Picasso, Klee, Cézanne and Braque) are just as fun and colorful. When I taught my Cubist-Inspired Picasso lesson to Kinders, I drew a fish, cut the fish into sections and shapes. Then, as a group, we put the fish together again in a new and different way. This exercise was really fun and emphasized the concept of abstraction (to take apart) and ultimately cubism.

My Easy Cubism Activities utilize the same concept: draw a familiar object then divide into shapes and lines. My third graders loved this project and although the instructions are the same, each child produced wildly different pieces.

I used Prismacolor markers for this project and are absolutely lovely. The colors are rich and heavy. Using card stock instead of sulfite paper makes coloring a pleasure. I read that using photo paper is a dream to use with markers so if you have a ream of that laying around, try it out!

Teach art from a cart? Learn why this lesson is a great choice by downloading this free checklist and lesson guide!

What do you think? Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a comment

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Is there a literature book you would recommend to go along with this “easy cubism” lesson? I love how some of your art lessons include reading of a literature book 🙂 Susan

Hi Susan, Great question. You could tie in a book on Picasso or Klee. Laurence Anholt’s The Girl with the Ponytail is and especially good one for cubism.

Does this packet include a picture to color THEN CUT and put back together? I love the fish you did in the beginning, simple enough for my first graders.

Hi Amanda, The package includes two print outs of the same object: one plain and one patterned coloring page. There are a few options to create your own cubist projects. You can color and cut if you wish. Patty

I’m trying to download this, it doesn’t seem to work

It’s in the ART THROUGH THE AGES bundle

Hi, i am very much interested to learn cubism. Mat i know if you have an on-line class on this subject? If you do, may i know how much. Thank you very much.

We have an enrollment right now for The Sparklers Club. Check it out! https://pages.deepspacesparkle.com/the-sparklers-club/

You are so good at this

In stores 8/21

- PRIVACY POLICY & TERMS OF SERVICE

Deep Space Sparkle, 2024

The {lesson_title} Lesson is Locked inside of the {bundle_title}

Unlocking this lesson will give you access to the entire bundle and use {points} of your available unlocks., are you sure, the {bundle_title} is locked, accessing this bundle will use {points} of your available unlocks., to unlock this lesson, close this box, then click on the “lock” icon..

Look Closer

All about cubism

Discover the radical 20th century art movement. This resource introduces cubist artists, ideas and techniques and provides discussion and activities.

Pablo Picasso Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913) Tate

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2024

What is cubism and why was it so radical?

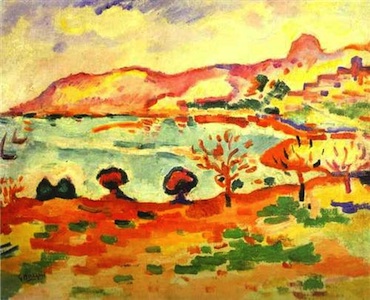

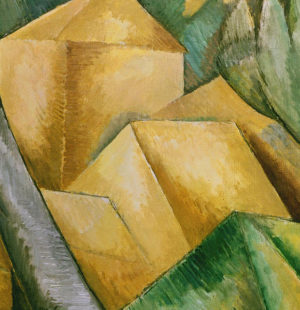

In around 1907 two artists living in Paris called Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque developed a revolutionary new style of painting which transformed everyday objects, landscapes, and people into geometric shapes. In 1908 art critic Louis Vauxcelles, saw some landscape paintings by Georges Braque (similar to the picture shown above) in an exhibition in Paris, and described them as ‘bizarreries cubiques’ which translates as ‘cubist oddities’ – and the term cubism was coined.

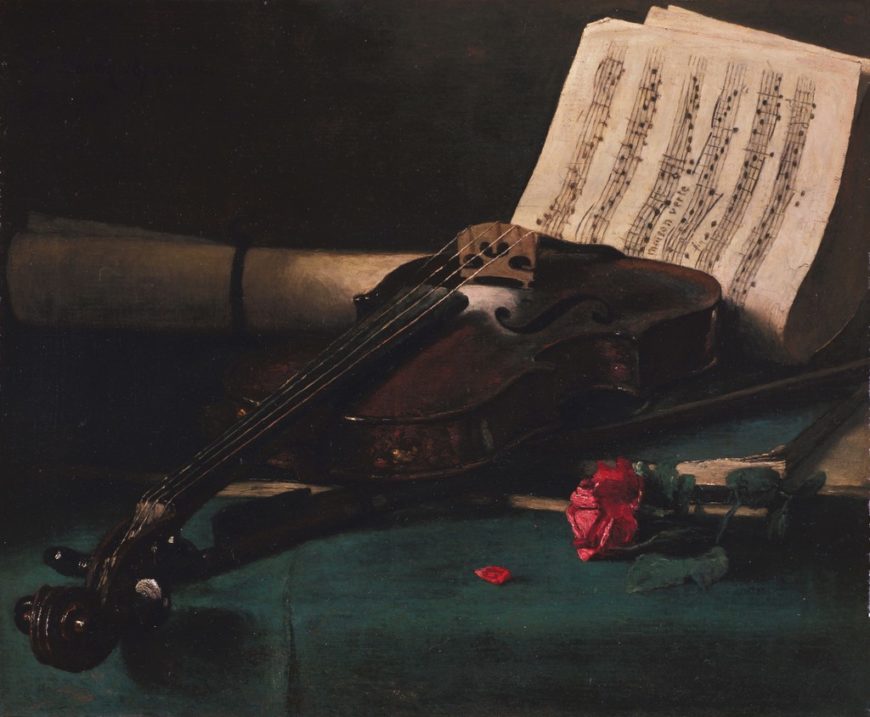

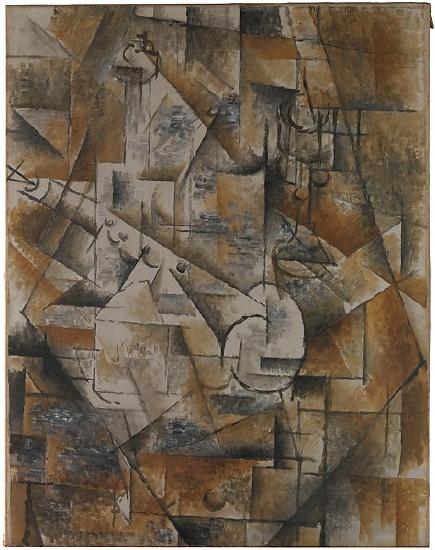

By comparing a cubist still life with an earlier still life painted using a more traditional approach, we can see immediately just what it is that made cubism look so radically different from earlier painting styles. Both paintings are of musical instruments. The first is by Edward Collier and was painted in the seventeenth century. The second is by cubist Georges Braque.

Edward Collier Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s ‘Emblemes’ (1696) Tate

Georges Braque Mandora (1909–10) Tate

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

Compare the way the instruments are painted in the paintings. Which look the most real? How has Collier made the objects in his painting look realistic? (Look at how he has used shading or tone , colour, perspective and also how he has applied the paint). What rules do you think the cubists broke?

Collier's Still Life looks realistic because...

- His use of colour to help us recognise the objects. A golden brown colour suggests the wood of the stringed instruments and table; the book and sheet music are black (ink) and white (paper); the grapes are a lush dark purple; and he has even cleverly recreated the metallic surface of the two-handled bowl using dark greys and whites

- His use of light and dark tones (shadows and highlights) to suggest the three-dimensional quality of the objects. Look at the side of the stringed instrument at the front of the painting. Light reflects off the raised surface closest to us, but as this curves away from us, the tone used is darker to suggest that it is more in shadow.The background is a shadowy dark space behind the table

- His use of perspective to create the impression of a real space with objects in the foreground looking bigger and clearer and objects behind looking smaller and less clear.

Braque's Mandora is different because...

- Although the shape of the mandora (a stringed instrument similar to a lute) is fairly clear, and if we look closely we can make out a bottle behind it, there is very little difference between the way Braque has painted the objects and the space around them. He has fragmented the whole image into tiny flat geometric shapes so the edges of the objects are less clear

- He has not used realistic colours for the different objects in the painting, instead he has used the same small range of muted colours – black, greys, ochres and earthy greens – for all the objects (no matter what they are) and the background

- He has not used perspective, or tone (light and shadow) to create the illusion of three-dimensional space or three-dimensional objects. Although there are lighter and darker tones within the painting, and these do sometimes create the appearance of three-dimensions (a dark tone is used for the side of the mandora making it look like a solid object); the tone is not always used in this way and sometimes seems confusing. The mandora, the objects behind it, and the background all seem to sit on the same level – on the flat surface of the picture, with no foreground or background, and no illusion of receding space.

Meet the cubists

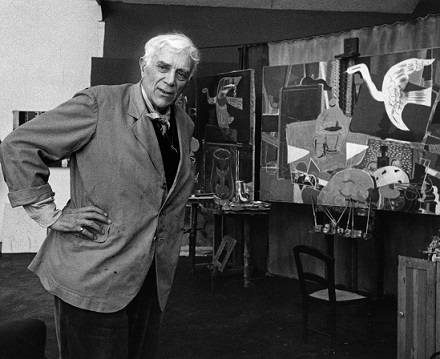

Brassaï, photo of Picasso in his studio at 23 rue La Boétie, standing in front of Rousseau’s Portrait of a Woman 1932. Musée Picasso © ESTATE BRASSAÏ -R.M.N.

Georges Braque , London 1946 (inner pages) from Tate Publishing

In 1907 Georges Braque visited Pablo Picasso’s studio. This studio visit marked the beginning of one of the most important friendships in the history of art. Over the next few months and years the two artists shared their ideas, scrutinized each other’s work, challenged and encouraged each other. At some stage in around 1907 or 1908 they invented an exciting new style of painting – cubism . Their close working relationship at that time was later described by Georges Braque:

The things that Picasso and I said to one another during those years will never be said again, and even if they were, no one would understand them anymore. It was like being roped together on a mountain

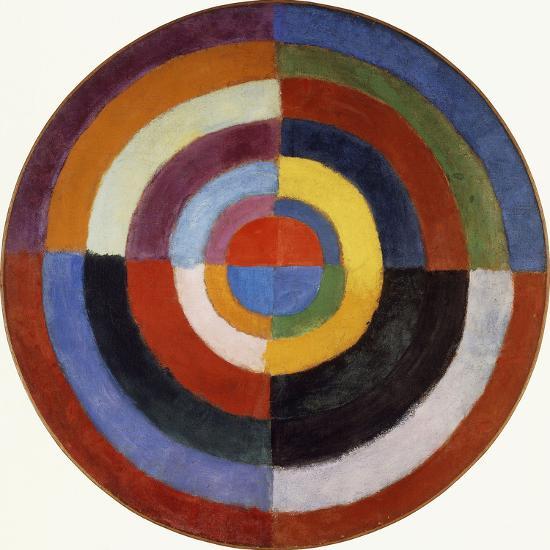

Picasso and Braque were soon joined in their art adventure by other artists who were experimenting with different ways of depicting the world around them. Artists such as Juan Gris , Albert Gleizes , Jean Metzinger and Robert Delaunay who all worked in a cubist style.

Cubism explained

Georges Braque Bottle and Fishes (c.1910–12) Tate

Cubism looks very different to lots of other styles of painting. How does it work? What were Braque and Picasso's reasons for turning their back on traditional techniques? How did the cubists develop their new style?

The illusion of space

Since the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, European artists had aimed to create the illusion of three-dimensional space in their drawings and paintings. They wanted the experience of looking at a painting to be like looking through a window onto a real landscape, interior, person or object.

How do you make things look three-dimensional on a two-dimensional surface? Techniques such as linear perspective and tonal gradation are used. Perspective involves making things look bigger and clearer when they are close up, and smaller and less clear when they are further away. By doing this you can create the illusion of space. Artists also use tones (shadows) to create the illusion of three-dimensional objects. By gradually changing the darkness of a shadow, you can make something look solid.

These drawings by J.M.W Turner show how perspective and tone (or shadow) can be used to create the illusion of real, solid three-dimensional objects.

Joseph Mallord William Turner Lecture Diagram 42: Perspective Construction of a Tuscan Entablature (c.1810) Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner Lecture Diagram 70: A Ruined Amphitheatre (c.1810) Tate

A new reality

The cubists however, felt that this type of illusion is trickery and does not give a real experience of the object.

Their aim was to show things as they really are, not just to show what they look like. They felt that they could give the viewer a more accurate understanding of an object, landscape or person by showing it from different angles or viewpoints, so they used flat geometric shapes to represent the different sides and angles of the objects. By doing this, they could suggest three-dimensional qualities and structure without using techniques such as perspective and shading.

This breaking down of the real world into flat geometric shapes also emphasized the two-dimensional flatness of the canvas. This suited the cubists’ belief that a painting should not pretend to be like a window onto a realistic scene but as a flat surface it should behave like one.

Look at this painting by Georges Braque of a glass on a table. Can you spot the techniques he has used to emphasize the flatness of the picture, but at the same time, made the objects look solid?

Georges Braque Glass on a Table (1909–10) Tate

The phases of cubism: Analytical vs synthetic

Cubism can be split into two distinct phases. The first phase, analytical cubism , is considered to have run until around 1912. It looks more austere or serious. Objects are split into lots of flat shapes representing the views of them from different angles, and muted colours and darker tones or shades are used. The second phase, synthetic cubism , involves simpler shapes and brighter colours (and looks more light-hearted and fun!)

Practical activities

David Hockney Caribbean Tea Time (1987) Tate

© David Hockney

Use these activity suggestions to explore ideas and create a cubist masterpiece updated for the twenty-first century.

Activity 1: Research influences

Paul Cézanne The Grounds of the Château Noir c.1900–6 Lent by the National Gallery 1997

Carved wooden female figure (minsereh) Mende, probably late 19th century AD, From Sierra Leone Trustees of the British Museum

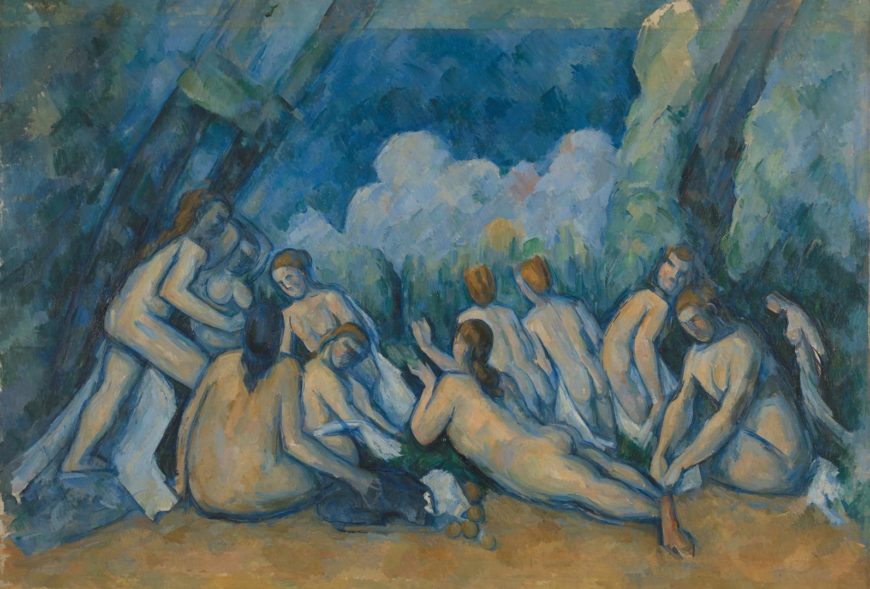

There were two key influences on the development of cubist style: the paintings of Paul Cézanne and sculptures created by non-European artists. Use these activities to explore these two artistic approaches

Cézanne’s approach

Braque and Picasso greatly admired Paul Cézanne . Cézanne’s paintings of figures and landscapes are made up of small planes (flat shapes) and repeated brush strokes. They often seem to be painted from slightly different viewpoints. It is this influence that we can see in the work of the cubists.

If you look at Cézanne’s painting of trees and rocks in the grounds of the Château Noir, the surface seems to vibrate with a mesh of tiny interlocking planes.

- Select a small section of the image and copy it, enlarging it so that it fills your page

- Use paint, crayons or pastels to copy the marks and colours

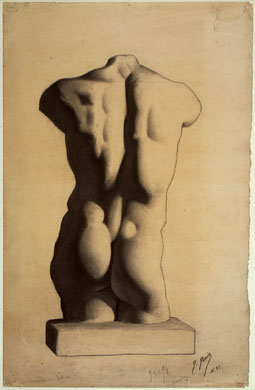

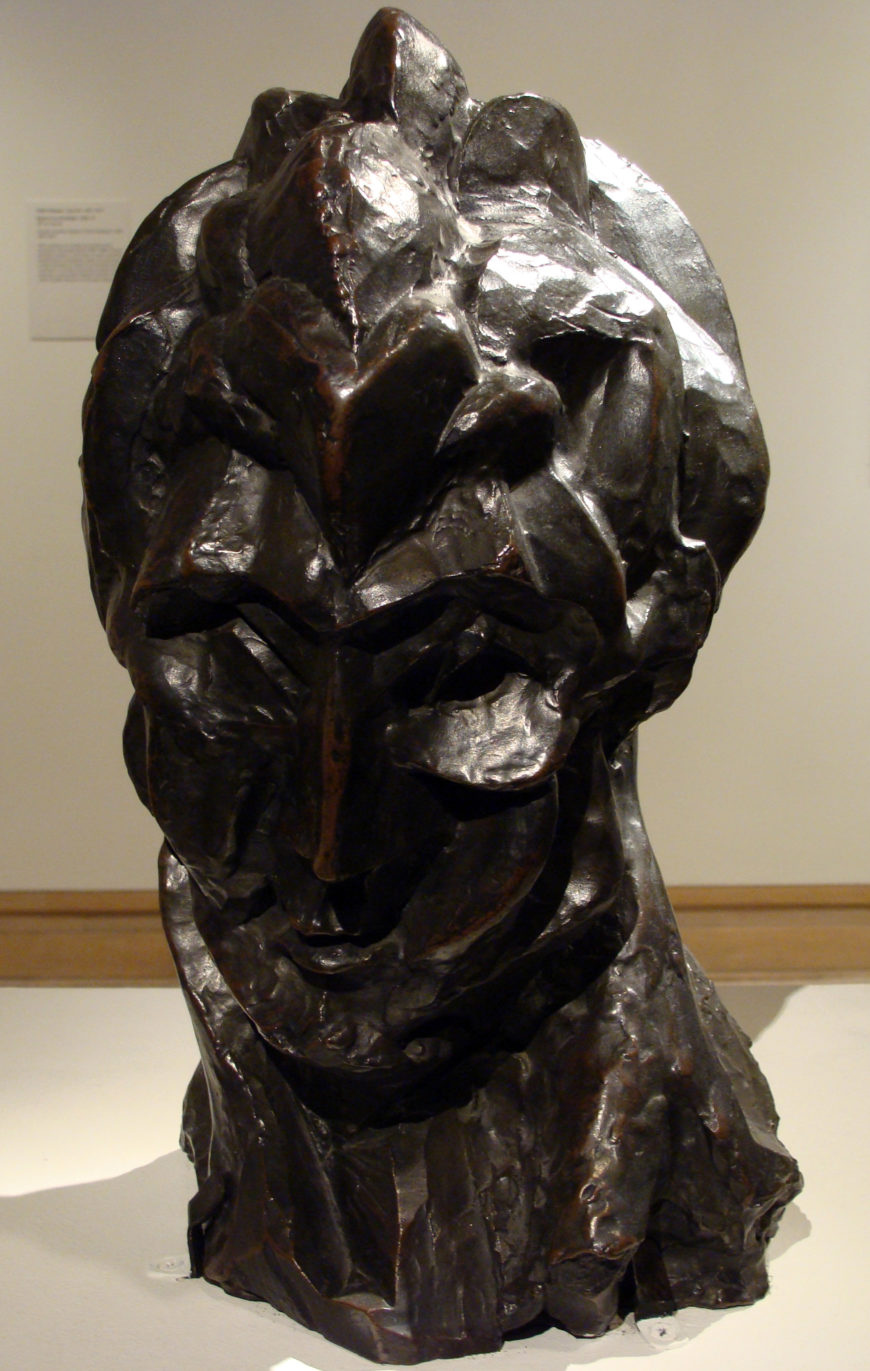

Sculptures from non-European cultures

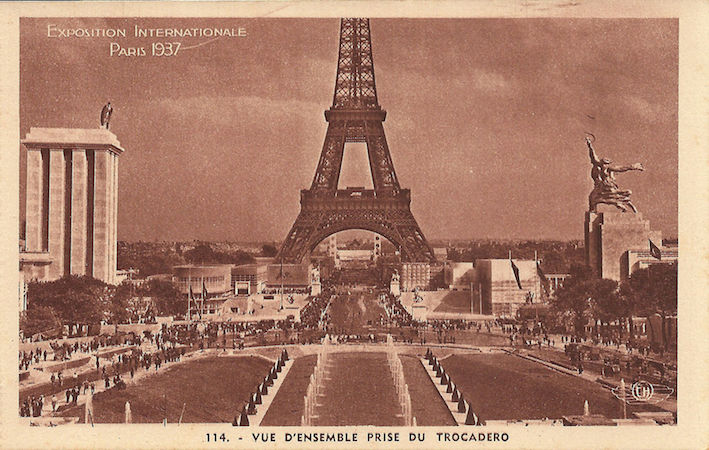

Picasso and Braque were amazed by the sculptures they saw in the Trocadero museum in Paris. Picasso described sculptures from French Polynesia and Africa as ‘the most powerful and most beautiful things the human imagination has ever produced’.

Look closely at the sculpture above. Think about the following and make notes in your sketchbook

- Where is it from?

- How big do you think it is?

- Is it realistic?

- Has the sculptor simplified the figure?

- Do parts of it seem exaggerated or emphasised?

- What does the sculpture make you think and feel?

- What do you think the sculpture was originally made for?

Create a portrait using sculptures from non-European cultures as your inspiration. This can be a self-portrait or a portrait of someone else.

- Use your notes about the sculpture you chose from the slideshow above to help you with approach and technique

- How has the sculptor simplified and exaggerated the forms. What effect does this have on your response to the work?

- Can you create a similar effect in your portrait?

Activity 2: Investigate viewpoints

The cubists wanted to show the whole structure of objects in their paintings without using techniques such as perspective or graded shading to make them look realistic. They wanted to show things as they really are – not just to show what they look like. They did this by:

- Emphasizing the flatness of the picture surface by breaking objects down into geometric shapes

- Depicting objects from lots of different angles. In this way they could suggest the three-dimensional quality of objects without making them look realistic.

Create a simple still life using the cubist technique of multiple viewpoints

- Choose three simple objects and group them together (e.g. trainer, mobile phone, apple, headphones, soft-drink can)

- Sketch or photograph the group of objects from four different viewpoints. (Viewpoints could include from the front, from above, from each side, from close-up, from far away…)

- Cut up each sketch or photograph into eight sections

- Choose two sections from each original sketch / photograph and put them together to form one image .

If you have access to picture editing software you can use this to create your picture. Use the tips below:

- Photograph your still life from four different viewpoints and save these images

- Select a small section from each photograph using the square marquee tool

- Open a new image and paste two sections from each original photograph to form your different viewpoint still life.

Activity 3: Explore shape, pattern, and texture

Juan Gris The Sunblind (1914) Tate

Pablo Picasso Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle (1914) Lent by the National Gallery 1997

Juan Gris Bottle of Rum and Newspaper (1913–14) Tate

From around 1912 Braque , Picasso , and other artists working in a cubist style such as Juan Gris , started to use simpler shapes and lines and brighter colours in their artworks. They also began to add textures and patterns to their work, often collaging newspaper or other patterned paper directly into their paintings. This approach was called synthetic cubism. Browse the slideshow to remind yourself what it looks like.

Create a still life in the synthetic cubist style that explores shape, pattern and texture. Use the three objects you selected earlier, but this time use only flat shapes, simple lines and patterns to depict them in a still life. Here are some ideas.

- You could draw a simple outline of the objects onto brightly coloured or patterned sheets of paper such as newspaper or wrapping paper. Cut these shapes out and collage them into your still life

- Think about the negative shapes (the shapes left in the paper once you have cut your object out of it). Could you add these to your still life?

- Look at the shadows made by the objects. How can you make these shadow shapes part of the work?

- If your objects include text or numbers (such as the title of a book or a brand name on trainers), use numbers or letters cut from a magazine or newspaper

- Don’t be afraid to mix media. Use charcoal or wax crayon to draw shapes or details over collage. Use paint to cover flat bright areas, or to add texture or pattern to your still life.

If you are still stuck for ideas, this animation may help!

- iMap animation: Pablo Picasso, Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle 1913

Activity 4: Be inspired by other artists

John Stezaker Third Person (1988–9) Tate

© John Stezaker

Phoebe Unwin Man with Heavy Limbs (2009) Tate

© Phoebe Unwin

Richard Hamilton Interior (1964–5) Tate

© The estate of Richard Hamilton

Albert Gleizes Painting (1921) Tate

Francis Bacon Three Figures and Portrait (1975) Tate

© Estate of Francis Bacon

Patrick Caulfield Hemingway Never Ate Here (1999) Tate

© The estate of Patrick Caulfield. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024

Braque and Picasso developed cubism a century ago, but artists and designers have been influenced by the ideas and techniques ever since. How have they updated cubism?

Choose a cubist-inspired artwork from the works above or from Tate’s collection . Make a quick drawing of it in your sketchbook. Think about the following and annotate (add notes to) your drawing with your thoughts:

- How do you think the artist was influenced by cubism?

- Why do you like the artwork? What does it make you think or feel?

- Is there anything in the artist’s approach that gives you ideas for how you could update cubism?

Activity 5: Create your own cubist artwork

You have investigated cubist sources and approaches and have researched how other artists have used cubist ideas and style. Now plan your artwork using what you have discovered, and update cubism for the twenty-first century.

- Review what you have found out about cubism

- Decide what you think are the key features of cubism. Which of these will you make use of in your artwork? List your ideas in your sketchbook

- Braque and Picasso painted ordinary objects that were part of their everyday lives. Think of objects that reflect your lifestyle and interests. Make a note of them in your sketchbook

- Braque and Picasso experimented with techniques and approaches. Can you think of ways you could use technology to make a state-of-the-art still life?

You should now have plenty of ideas for your updated cubist still life. Picasso and Braque were innovators, experimenting with radical new approaches in the way they depicted the world they saw around them. Their artworks still seem exciting and daring to us one hundred years later. Make sure your artwork has what it takes to inspire others and stands the test of time!

Cubist artists in the collection

Pablo picasso, georges braque, related terms and concepts.

Cubism was a revolutionary new approach to representing reality invented in around 1907–08 by artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They brought different views of subjects (usually objects or figures) together in the same picture, resulting in paintings that appear fragmented and abstracted

Orphism was an abstract, cubist influenced painting style developed by Robert and Sonia Delaunay around 1912

Analytical cubism

The term analytical cubism describes the early phase of cubism, generally considered to run from 1908–12, characterised by a fragmentary appearance of multiple viewpoints and overlapping planes

Synthetic cubism

Synthetic cubism is the later phase of cubism, generally considered to run from about 1912 to 1914, characterised by simpler shapes and brighter colours

Creativity in the classroom and in life

Cubist Drawing with video tutorial

Miriam | May 12, 2021 April 9, 2021 | Art Techniques , Mixed media

You need just a drawing paper, some colored pencils and watercolors to create this still life in the style of CUBISM . Cubism was a revolutionary new approach to representing reality invented in around 1907–08 by artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They brought different views of subjects (usually objects or figures) together in the same picture, resulting in paintings that appear fragmented and abstracted.

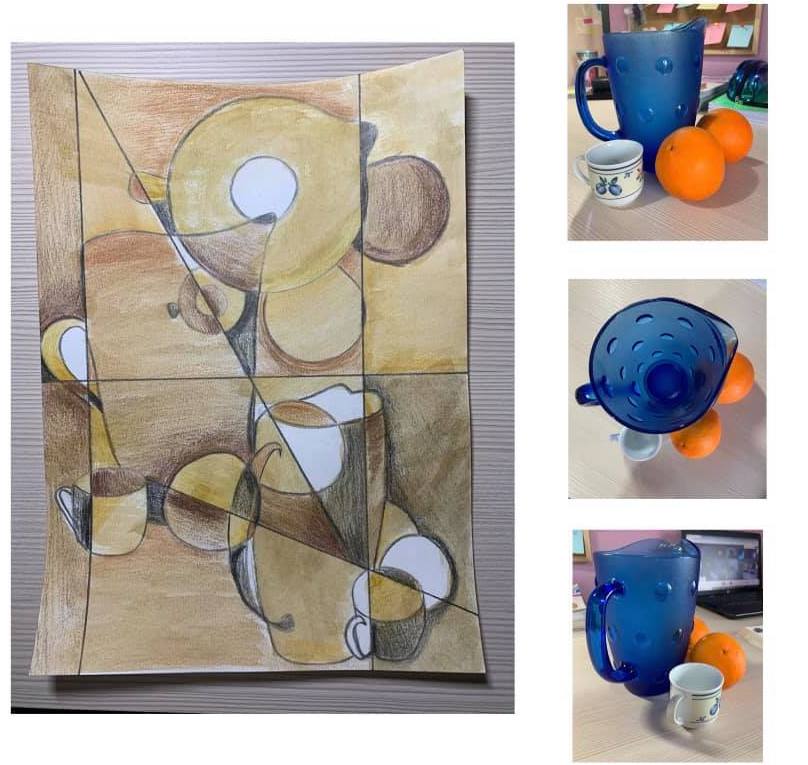

To imitate this pictorial style we need to take three pictures of a still life: we can prepare it on a table, arranging some objects such as vases, bottles, glasses, fruit. We take three different shots of the same still life, changing framing and taking a front view, a top view and a three-quarter view.

We copy the pictures, overlapping the drawings on the same sheet of paper. After that, we color the drawing with colored pencils and paint it with watercolors (or coffee as I suggested in the video-tutorial. It was a time of lock down with closed shops!). Here below the video tutorial

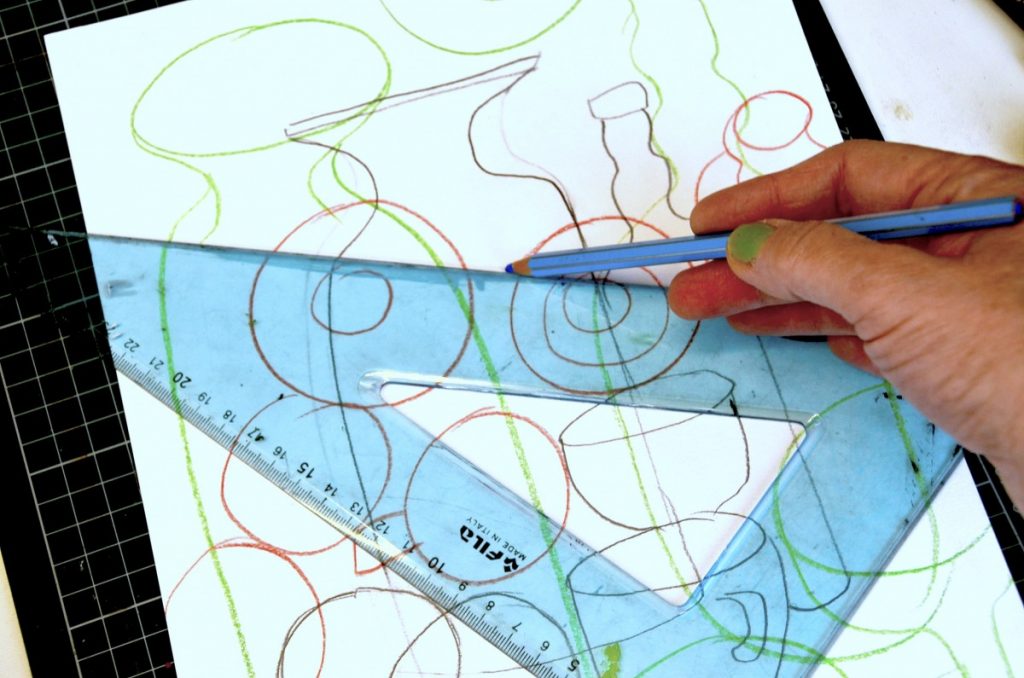

You copy the three pictures on the same sheet of paper, overlapping the three different views.

Then with a ruler, you draw some straight lines that “break” and further break down the shapes.

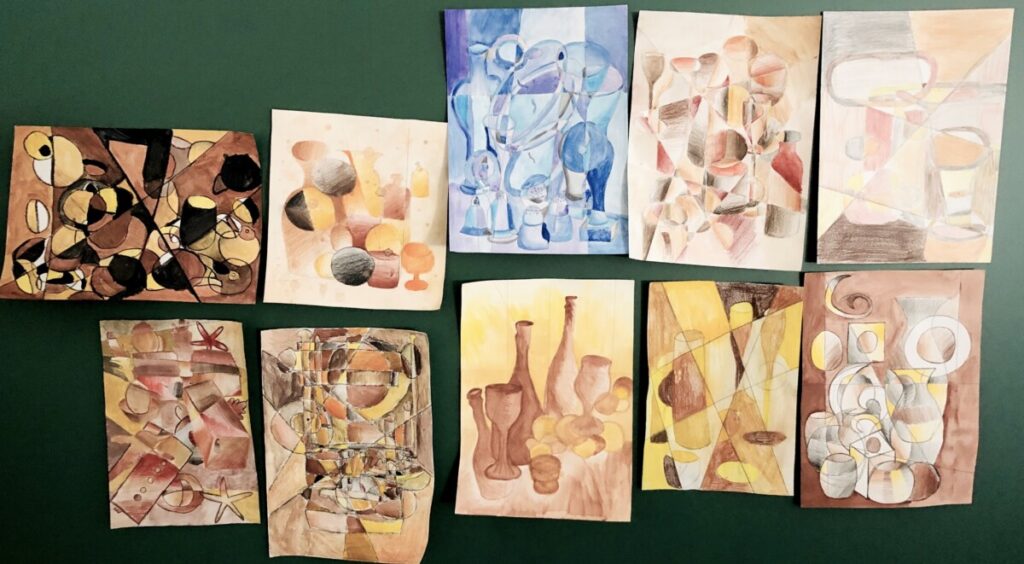

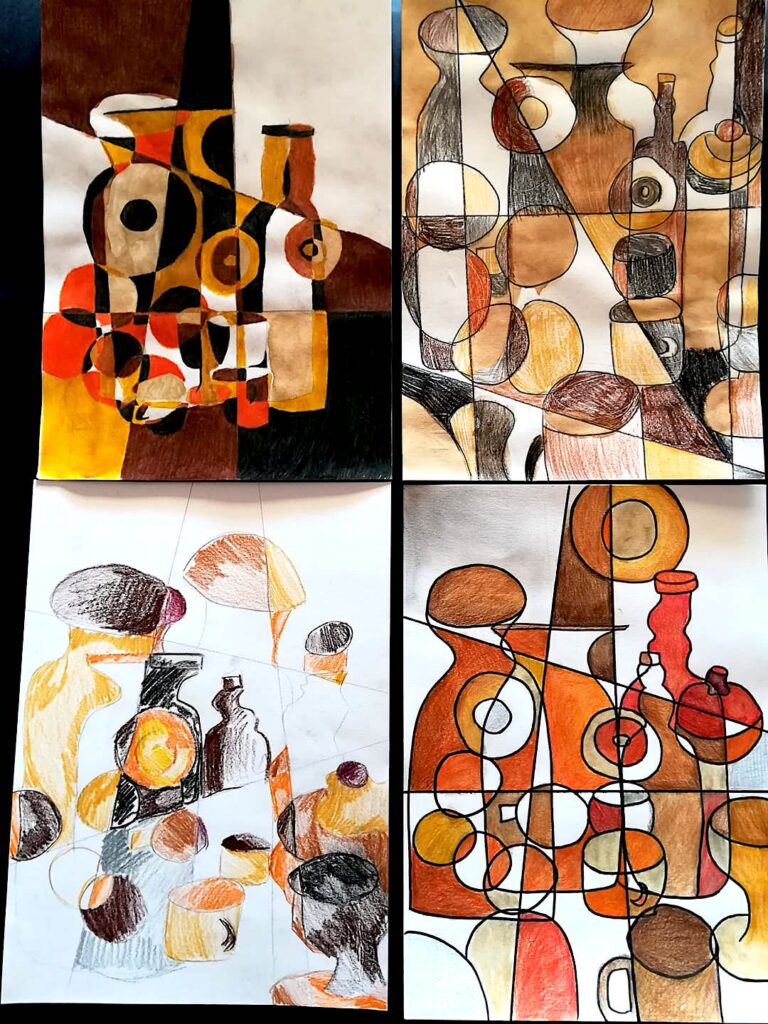

The drawing is colored with colored pencils, choosing earthy, brown and monochromatic tones in the style of Analytical Cubism by Braque and Picasso.

Subsequently, some areas of the drawing are painted with watercolors (or coffee as you can see in the video), leaving a few small white areas. Eventually, once dry, further pencil shades can be added.

Here below some student’s drawings:

Here the drawings of Maria Castellano students from the Middle School G. Pascoli in San Giorgio Ionico (Ta) Italy , completed of still lives pictures. Thanks for sharing!

Here below the drawings of Gisella Nabissi students from the Middle School Giovanni III in Mogliano (MC) Italy . These works are full of variety, personality, and talent!

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

Copying a portrait using the Grid Method

Mandala with color theory, 1 thought on “cubist drawing with video tutorial”.

Hi Miriam… Love your site and the work you are doing! How long did it take for the children to do that assignement? Regards/Jorge

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.4: Cubism + early abstraction (I)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 107365

Cubism and early abstraction c. 1907 - 1939

A new, modern world demanded new ways of seeing and representing the things in it.

The Case for Abstraction

by THE ART ASSIGNMENT

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Speaker: Sarah Urist Green

Additional resources:

Abstract art definition from the Tate

Abstract art resources from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Cubism c. 1907 - 1939

Picasso and Braque revolutionized painting with their new approach to representation.

Beginner's guide to Cubism

Pablo picasso and the new language of cubism.

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Pablo Picasso, The Guitarist , 1910, oil on canvas, 100 x 73 cm (Centre Pompidou, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Inventing Cubism

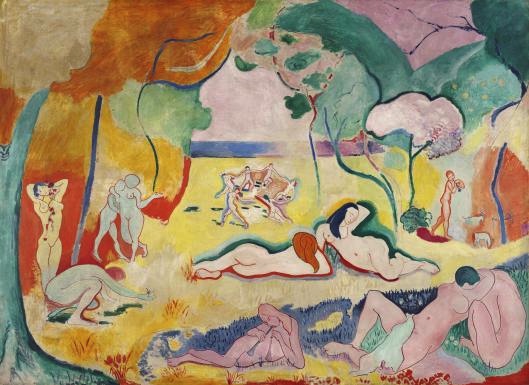

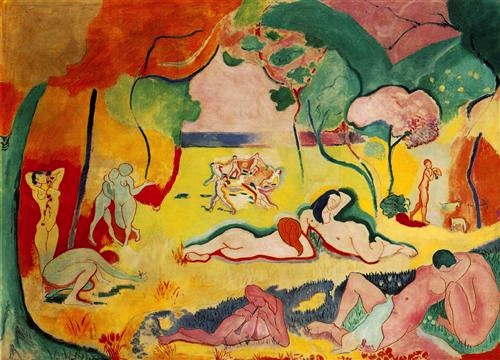

During the summer of 1908, Braque returned to Cézanne’s old haunt for a second summer in a row. Previously he had painted this small port just south of Aix-en-Provence with the brilliant irrevent colors of a Fauve (Braque along with Matisse, Derain, and others defined this style from about 1904 to 1907). But now, after Cézanne’s death and after having met Picasso, Braque set out on a very different tack, the invention of Cubism.

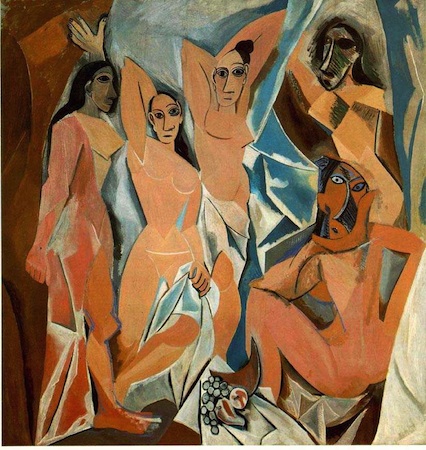

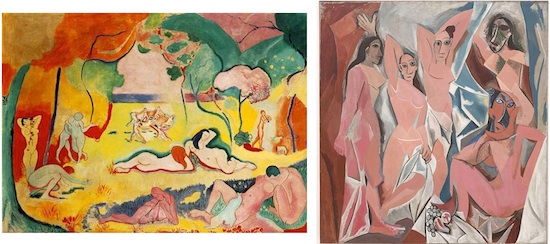

Cubism is a terrible name. Except for a very brief moment, the style has nothing to do with cubes. Instead, it is an extension of the formal ideas developed by Cézanne and broader perceptual ideas that became increasingly important in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These were the ideas that inspired Matisse as early as 1904 and Picasso perhaps a year or two later. We certainly saw such issues asserted in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. But Picasso’s great 1907 canvas is not yet Cubism. It is more accurate to say that it is the foundation upon which Cubism is constructed. If we want to really see the origin of the style, we need to look beyond Picasso to his new friend Georges Braque.

A New Perspective

The young French Fauvist, Georges Braque that had been struck by both the posthumous Cézanne retrospective exhibition held in Paris in 1907 and his first sight of Picasso’s radical new canvas, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Like so many people that saw it, Braque is reported to have hated it—Matisse, for example, predicted that Picasso would be found hanged behind the work, so great was his mistake. Nevertheless, Braque stated that it haunted him through the winter of 1908. Like every good Parisian, Braque fled Paris in the summer and decided to return to the part of Provence in which Cézanne had lived and worked. Braque spent the summer of 1908 shedding the colors of Fauvism and exploring the structural issues that had consummed Cézanne and now Picasso. He wrote:

It [Cézanne’s impact] was more than an influence, it was an invitation. Cézanne was the first to have broken away from erudite, mechanized perspective… \(^{1}\)

Like Cézanne, Braque sought to undermine the illusion of depth by forcing the viewer to recognize the canvas not as a window but as it truly is, a vertical curtain that hangs before us. In canvases such as Houses at L’Estaque ( 1908), Braque simplifies the form of the houses (here are the so called cubes), but he nullifies the obvious recessionary overlapping with the trees that force forward even the most distant building.

Brothers of Invention

When Braque returned to Paris in late August, he found Picasso an eager audience. Almost immediately, Picasso began to exploit Braque’s investigations. But far from being the end of their working relationship, this exchange becomes the first in a series of collaborations that lasts six years and creates an intimate creative bound between these two artists that is unique in the history of art.

Between the years 1908 and the beginning of the First World War in 1914, Braque and Picasso work together so closely that even experts can have difficulty telling the work of one artist from the other. For months on end they would visit each others studio on an almost daily basis sharing ideas and challenging each other as they went. Still, a pattern did emerge and it tended to be to Picasso’s benefit. When a radical new idea was introduced, more than likely, it was Braque that recognized its value. But it was inevitably Picasso who realized its potential and was able to fully exploit it.

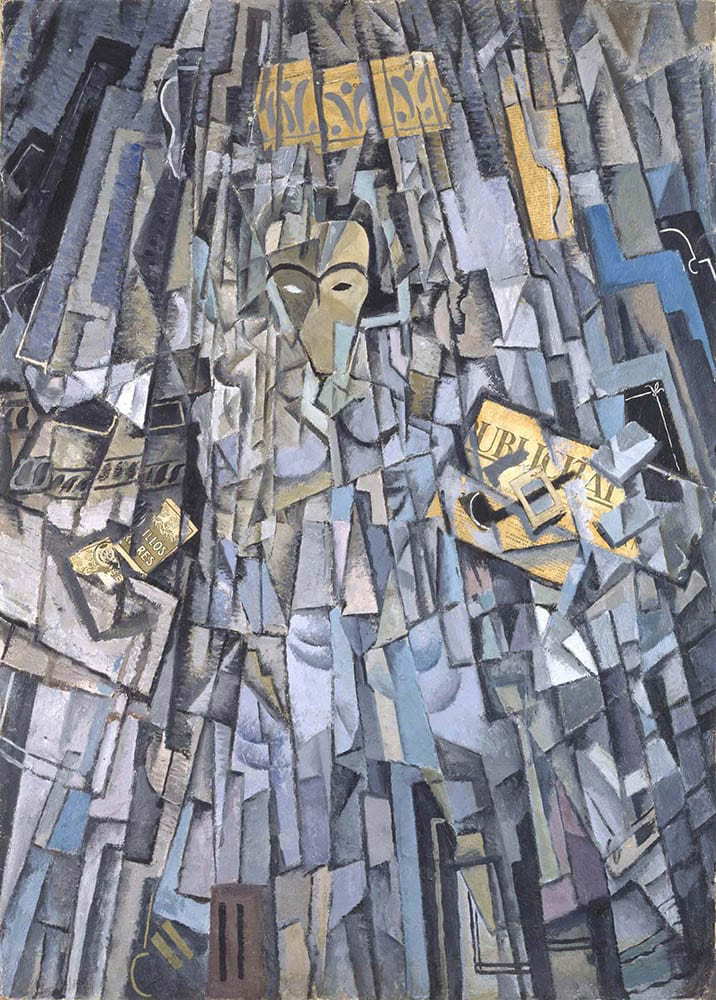

By 1910, Cubism had matured into a complex system that is seemingly so esoteric that it appears to have rejected all esthetic concerns. The average museum visitor, when confronted by a 1910 or 1911 canvas by Braque or Picasso, the period known as Analytic Cubism, often looks somewhat put upon even while they may acknowledge the importance of such work. I suspect that the difficulty, is, well…, the difficulty of the work. Cubism is an analysis of vision and of its representation and it is challenging. As a society we seem to believe that all art ought to be easily understandable or at least beautiful. That’s the part I find confusing.

1. As quoted in William Rubin, Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism , New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1989, p.353.

Cubism on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Cubism and multiple perspectives

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

At first sight the objects in Georges Braque’s Pitcher and Violin appear arbitrarily distorted, but they are not. One tactic that Braque uses here is depicting objects from multiple perspectives. While most of Braque’s violin is depicted frontally, like an illustration in an encyclopedia, the scroll at the top of the neck is represented from the side, and the bridge that holds the strings over the neck and sound board has been flipped up.

The pitcher is also depicted mostly from the side, but we see the top rim from above on the left-hand side, while the spout is depicted from a slightly less elevated angle. Similarly, while Braque appears to have depicted the violin standing improbably on its bottom edge, it is more likely that we are expected to understand it as lying flat on a table. Thus, we are looking down on the violin at the same time as we look straight ahead at the body of the pitcher and the wall behind the table.

Cubism as higher truth

This use of multiple perspectives became a hallmark of the Cubist style, but Braque and Picasso never explained why they employed this technique. One common contemporary interpretation argued that the use of multiple perspectives allows greater truth and accuracy than the traditional naturalistic style that had dominated art since the Renaissance. In 1912, the writer and art critic Jacques Rivière argued that linear perspective creates unrealistic distortions. For example, if we stand in the middle of railroad tracks, they appear to converge and meet at a point, when in fact they remain parallel.

François Bonvin’s painting of a violin shows how much the instrument is skewed and distorted when viewed in perspective. Parts nearer the viewer are larger than parts further away, and some parts are compressed by foreshortening while others are occluded entirely. Rivière wrote that such distortions are corrected in real life simply by moving around objects to see their true shapes.

A step to the right and a step to the left [can] complete our vision. The knowledge we have of an object is … a complex sum of perceptions … the object must always be presented from the most revealing angle. Jacques Rivière, “Present Tendencies in Painting” (1912), as translated in Edward Fry, ed., Cubism (New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 77.

Braque represents the key parts of the violin from the most revealing angle. For example, the scroll is flipped to the side because if viewed from the front like the rest of the violin, it would not be visible at all. At the same time, though, if the scroll were viewed from the side, we would only see two of the tuning pegs, so Braque flips the view again to straight on so that all four pegs are visible.

Perspective is a deliberate lie

In 1912, the writer Olivier-Hourcade provided another example of how Cubist paintings correct the distortions of perspective:

The painter, when he has to draw a round cup, knows very well that the opening of the cup is a circle. When he draws an ellipse, therefore, he is not sincere, he is making a concession to the lies of optics and perspective, he is telling a deliberate lie. Olivier-Hourcade, “The Tendency of Contemporary Painting” (1912), as translated in Fry, Cubism , p. 74.

Look at all of the ellipses (flattened circles) in the Heda still-life above: the lip of the glass, the goblet, and the silver pedestal bowl, as well as the two pewter plates and the sliced lemon. All of these shapes are circles in real life; they only appear to be ellipses because of the angle from which they are viewed. The painter can correct this illusion simply by depicting these shapes from straight on, so the circle reveals its true shape.

Recognizing objects in Cubism

The subject of this still life may be difficult to discern, but with the help of the title we can begin to pick out the represented objects. The clarinet is the white rectangular shape in the left of the painting. Four finger holes extend up its length, which is shaded with chiaroscuro to suggest its tubular volume.

Note that while the bulk of the instrument is seen from the side, the opening at the base in the center of the painting is round, and a semicircle and schematic triangle at the other end by the edge of the canvas suggest the wedge-shaped cut out of the mouthpiece where the reed sits.

Above the clarinet’s finger holes, we can see a wine bottle with schematic, squared-off shoulders. Its transparency is indicated by the fact that we can see the clarinet through it. Notice that here, too, while we see the bulk of the bottle from the side, Braque has rendered the bottle’s mouth as a circle, as though seen from above, while a quarter-circle indicates the round base below.

With familiarity, we can begin to recognize objects in Cubist still-lifes even when they are not explicitly mentioned in the title. In the upper right quadrant of this painting there is a stemmed glass, again seen mostly from the side, but circles at the base, lip, and stem indicate the perfect roundness of those parts.

An art of conception, not perception

Jacques Rivière also argued that monochromatic color and inconsistent lighting are more truthful means to depict reality than traditional naturalism. As the Impressionists had demonstrated, the appearance of objects changes radically in different kinds of light.

Monochromatic color eliminates the variables of lighting to represent objects in their true form, as we know them to be, rather than showing them distorted by our vision. For this reason, Cubism was often seen as an art of conception rather than perception. Cubist paintings represented the composite idea of objects that we have in our heads, rather than rendering objects from one point of view, at one moment in time, and in one kind of light.

Cubism vs. illusionism

Braque and Picasso were well aware of how revolutionary their new way of representing objects was. As if marking the very different approaches to “realism” employed by Cubism and traditional naturalism, Braque painted a nail in the top center of Pitcher and Violin . Although it is rendered in a relatively cursory manner, its darkness and cast shadow make it appear at first sight as though it were a real nail pinning the painting to the wall.

This refers to a tradition of nineteenth-century trompe l’oeil painting that was the culmination of Renaissance naturalism. Trompe l’oeil paintings are so detailed and convincing that the viewer is fooled into thinking they are real.

Everything in this Harnett still life is painted: the violin, the door, the rusty hinges and nails, the lock, and even the wooden frame. Although this is the style that is usually taken as being the most “realistic,” it is in fact an illusion: it’s only paint on canvas. The use of multiple perspectives to show objects’ true shapes is arguably more true to reality.

Incomprehensible fins

The idea of Cubism as a more truthful representation of objects based on the use of multiple perspectives to build up a composite, conceptual representation was one of the dominant interpretations of the movement. It does not, however, fully account for what we see in the works, and it should be remembered that Braque and Picasso did not articulate or endorse this interpretation.

One thing that this interpretation does not account for is what can be called the “background noise” of Cubist paintings. While some shapes in Braque’s Pitcher and Violin and Clarinet and Bottle can be seen as articulating the shapes of those objects from multiple perspectives, others appear to be just arbitrary fragments. Also, as the style of Cubism evolved, Braque and Picasso broke objects up into smaller and smaller facets, until they are virtually unrecognizable in a shallow plane of monochromatic shards.

More oddly still, not only are the objects themselves faceted, it appears as though the empty space between them has also been shattered into facets. In some works, paint is applied in an almost brick-like fashion, further contributing to the background noise, until only a few clues (and the titles) hint at what is being represented.

Rivière found such paintings perplexing:

To each object they add the distance which separates it from neighboring objects … and in this way they show it prolonged in all directions and armed with incomprehensible fins. The intervals between forms—all the empty parts of the picture, all the places in it occupied by nothing but air, find themselves filled up by a system of walls and fortifications. Jacques Rivière, “Present Tendencies in Painting” (1912), as translated in Edward Fry, ed., Cubism , p. 79.

Although this is a fairly accurate description of late Cubist painting, Rivière was unable to explain its motivations and claimed that these were “mistakes.” His highly rational view of Cubism led him to dismiss the elements of the style that did not conform to his ideas. Rivière’s “multiple perspectives as higher truth” interpretation is compelling, and as we have seen backed by some visual evidence, but there are clearly other facets to Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubism.

Edward Fry, ed., Cubism (New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1966)

Read and listen to more about Still life with Banderillas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

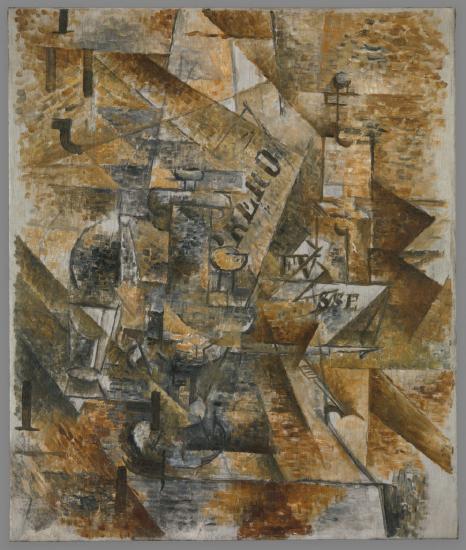

Synthetic Cubism, Part I

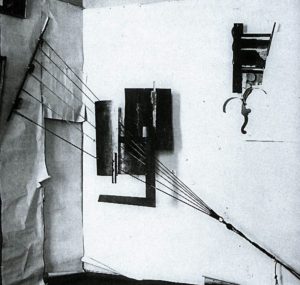

Starting in 1912, surprising new elements begin to turn up in works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque: cut-up pieces of newspaper, wallpaper, construction paper, cloth, and even rope. Although the resulting collages are visually very different from the largely monochromatic oil paintings most commonly associated with the movement, they are still considered to be part of Cubism.

Partly this is because these works often included drawings that use techniques associated with Cubism, such as deconstructing objects into fragmented, angular forms seen from multiple perspectives. Beyond this similarity, though, there is also another, more conceptual one. This new phase of Cubism is also dedicated to exploring the ambiguities of representation, now on an even wider scale.

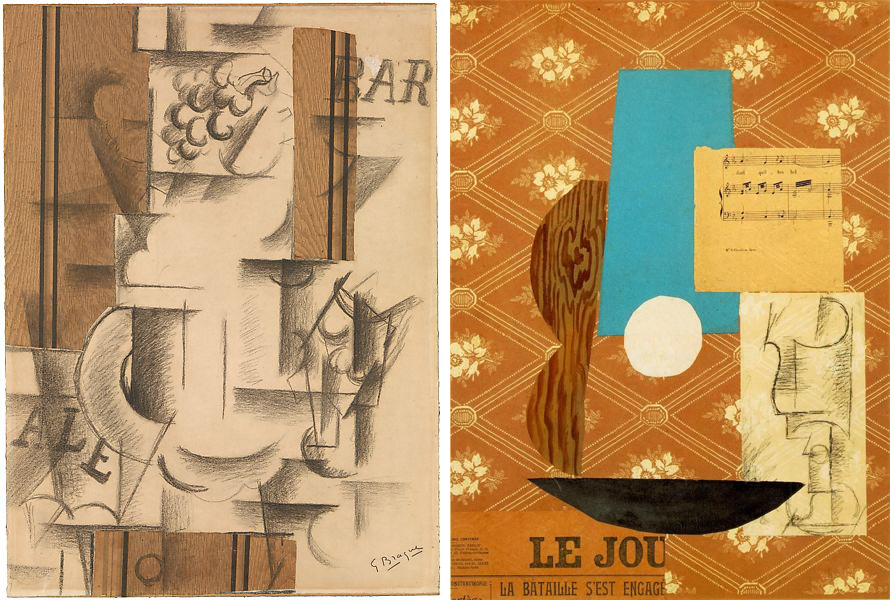

Fruit Dish and Glass is Braque’s first work using papier collé (pasted paper), a subset of collage made using only paper. Picasso’s first collage, Still Life with Chair Caning preceded Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass by a few months and was made from a variety of materials including oilcloth and rope. Papier collé was a central medium in the second phase of Braque’s and Picasso’s joint Cubist investigations commonly known as Synthetic Cubism.

Retreat from abstraction

During this phase both artists retreated from the verge of total abstraction they had reached in their late Analytic Cubist paintings . Synthetic Cubist works use multiple forms of representation, combining the abstracted forms of Analytic Cubism with color, collage, and even sometimes naturalistic representations, to create a complex whole.

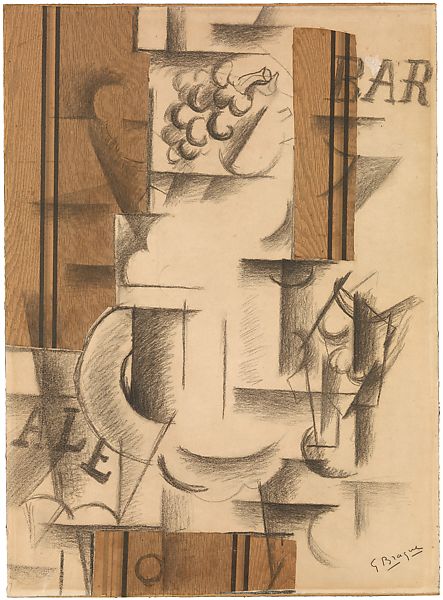

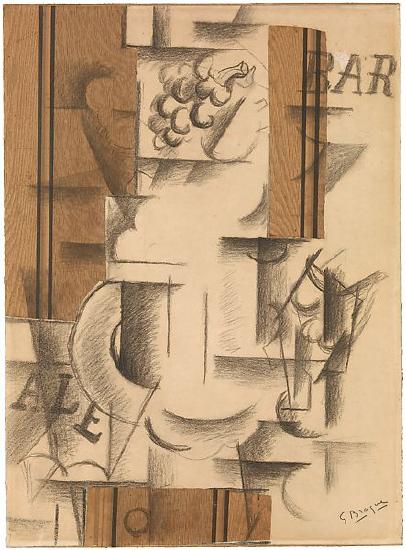

In Fruit Dish and Glass , Braque combines Cubist drawing with illusionistic representation, words, and decorative paper printed with a wood grain pattern ( faux bois ). At the top we see a bunch of grapes drawn relatively naturalistically, with light and shade defining its three-dimensional forms. The remaining still-life objects are depicted in an Analytic Cubist style that deconstructs them into arcs, cylinders, and flat planes representing a fruit dish, plates, and glasses on a table. The words “BAR” and “ALE” are frequently seen on signs and labels in cafés and indicate the general location of the still life.

References to traditional illusionism

Charcoal drawing extends over the strips of wood grain paper that frame and anchor the central forms. The two vertical strips in the upper portion represent wood paneling on a café wall behind the still life, while the horizontal strip below represents a wooden table supporting the dishes and fruit. A circle drawn on the lower strip of wood grain paper suggests the round knob of a drawer pull. This is a reference to illusionistic paintings, which often depict handles and knobs facing the viewer to enhance the sense of the objects being real and within easy reach.

The naturalistic grapes framed by lines and pasted paper at the top of the work are also a specific reference to the Western tradition of illusionistic representation. A famous story from Ancient Greece describes how the painter Zeuxis was so skilled an artist that birds tried to eat the grapes he painted. Braque centers his drawn grapes as a well-known example of traditional naturalism and then surrounds them with alternative strategies of representation.

Signifying real objects by other means

The Cubist drawings of suggestive geometric forms are, like the words BAR and ALE, a means of referring to or signifying real objects. If we know the language we know what a word signifies; this is true of French and English, and it is (at least theoretically) true of Cubist forms as well. Once we are aware of Cubist conventions for drawing we can recognize that certain relationships of lines and shapes signify fruit, a glass, or a face. The wood grain paper is also a means of signification. The represented texture refers to the physical materials in the scene, providing further information.

In addition, wood grain paper is, like the drawn grapes, an illusion. The naturalistically depicted grapes represent the central achievement of the European fine art tradition. The wood grain paper is, by contrast, a cheap mass-produced item used for decorative purposes. Its presence undermines the exalted value of artistic skill in creating illusionistic representations, and demonstrates another feature of synthetic Cubism: the collapse of distinctions between “high” art and the cheap, ephemeral materials and techniques of mass-produced design.

A kind of certainty

Braque later wrote:

The papiers collés in my drawings have also given me a kind of certainty. Georges Braque, “Thoughts on Painting” (1917)

This is generally understood to mean that they allowed him a way to retreat from the increasingly unmoored abstraction of late Analytic Cubism and anchor his works more solidly in relation to reality. The vaporous spaces and ambiguous forms of Analytic Cubist paintings like The Portuguese are, however, replaced by a different type of ambiguity resulting from the complex and shifting relationships of disparate materials and modes of signification.

Braque’s association of papiers collés with certainty should also be understood in terms of literalism and materiality. Picasso and Braque often employed collage elements as a shortcut means to represent objects. A newspaper in a still life of a café table will be represented by simply gluing newspaper to the picture plane, rather than painstakingly imitating its appearance using paint. Similarly, literal wallpaper is used to represent the presence of wallpaper in the scene, and the actual label is used to show a label on a bottle of wine. This is a form of playful one-upmanship of the Western tradition of naturalistic depiction: the artist now offers reality itself, rather than illusion.

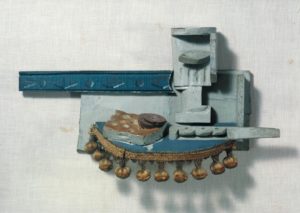

Collage elements also enhance the physical and tactile qualities of the artwork, which increasingly interested both Braque and Picasso. During this period they both also made sculptures and created pronounced surface textures in their paintings by adding sand, sawdust and other grainy materials to paint.

The strips of wood-grain paper in Fruit Dish and Glass confront the viewer with powerful dark shapes, which create a visually strong frame for the more immaterial charcoal drawing on white paper. In addition, the way the drawing continues onto the pasted paper enhances the typically Cubist interest in the tension between literal flatness and represented spatial depth.

Multiple readings

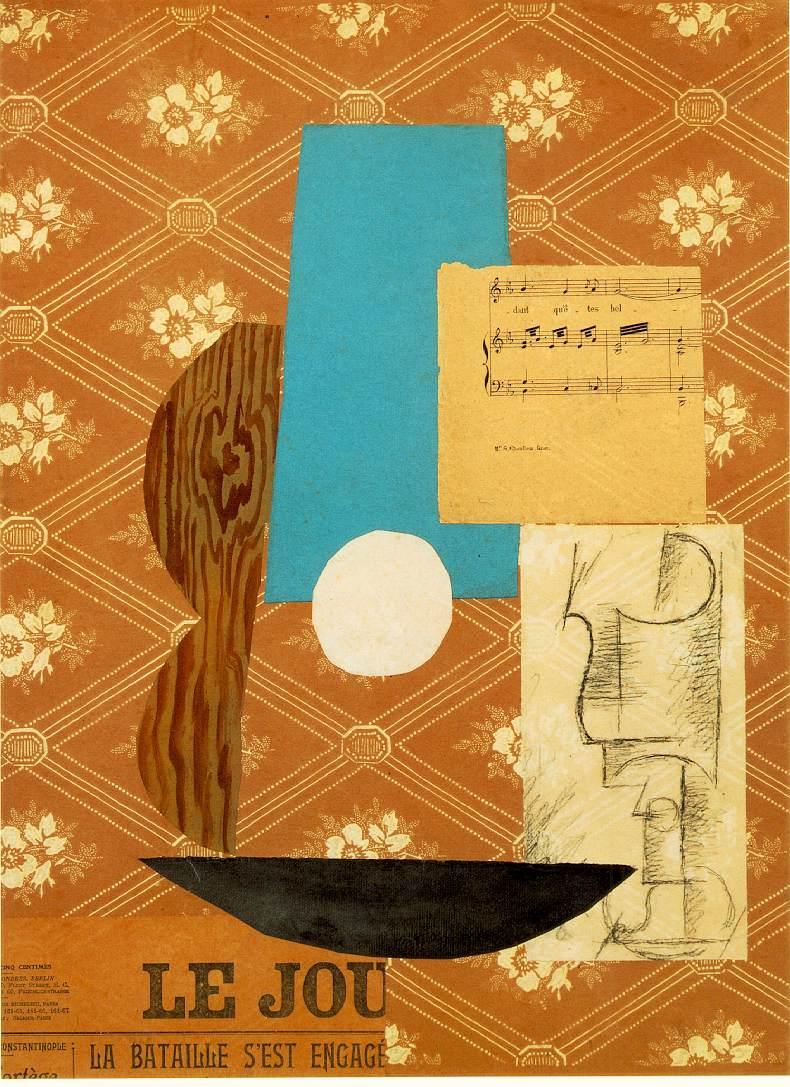

In Siphon, Glass, Newspaper and Violin , Picasso displays the multiple ways charcoal drawing and papier collé can be used to represent objects. For example, on the left newspaper is cut into the shape of a siphon, while on the right it is used as a surface for drawings of a glass and part of a violin. Its edges also define the left side of the violin’s upper body and neck.

Analytic cubist techniques are used to depict the glass, violin, and top of the siphon from multiple perspectives , while on the far right, paper painted with illusionistic wood grain indicates the violin’s material. In the center the word ‘JOURNAL’ (the French word for newspaper) cut from a newspaper’s masthead represents that object in a particularly direct and literal way. Although we are not offered a coherent visual illusion of the objects in the title, these multiple media and representational strategies combine to give us all of the relevant information.

Papier collé and collage not only anchored Cubist forms more firmly as distinct material objects, they also gave the artists a particularly rich means for generating multiple possibilities of meaning through a combination of media, representational strategies, and suggestive shapes and their formal relationships. Collage shapes, materials, colors, and words all contribute to the complex significations that proliferate in Synthetic Cubism.

Read about Fruit Dish and Glass at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Synthetic Cubism, Part II

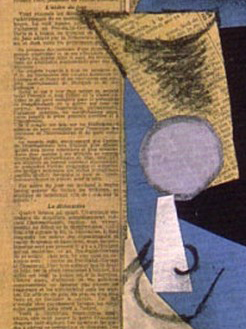

Pablo Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass is generally thought to have been made as a response to Georges Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass . Both works bring a new tool into the already-complex collection of Cubist techniques of representation — the use of collage.

A wealth of associations

The subject of Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass is familiar from earlier Analytic Cubist paintings , which frequently depict café tables with drinks, newspapers, and musical instruments . Here, however, the abstracted geometric forms of Analytic Cubism are limited to the charcoal drawing of the glass on paper pasted on the right. It is one element in the collage, which includes seven different types of paper arranged on a wallpaper ground.

The pattern of the wallpaper is a diagonal lattice that frames flowers and recalls the overall patterns of lattices and grids that structure earlier Analytic Cubist paintings such as Braque’s Piano and Mandola .

While Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass used only one type of pasted paper (the printed wood grain), Picasso uses many, and demonstrates that a wealth of associations can be generated from their juxtaposition.

Patterns of formal relations

An intricate pattern of formal relations is created between the varied shapes and colors of the pasted paper, which also generate a complex set of possible readings. The guitar is signified by multiple cut-paper elements.

On the left, the hand-painted wood grain paper cut into a double curve suggests the material and shape of the guitar’s body. A vertical trapezoid of blue paper is the neck in perspective, while the shallow black curve below stands for both the bottom of the guitar and the leading edge of the circular table on which the still-life sits.

In the center of the image, the white paper circle representing the sound hole in the guitar body looks like a hole cut out of the picture, while the fragment of sheet music simultaneously refers to itself, and to the sounds emanating from the instrument.

The glass drawn in charcoal is somewhat overwhelmed by the strong shapes of the pasted papers, but its ghostly appearance, as well as the semi-transparency of the paper on which it is drawn, suggests the transparency of glass. It is brought into the composition by the use of a visual rhyme — the circular lip of the glass directly echoes the white circle of pasted paper to the left.

The importance of text

One topic of debate among art historians has been the importance of the legible texts in Cubist collages. In this instance, it is generally agreed that the newspaper text in the lower left is relevant. The headline “La Bataille s’est engagé” (the battle has begun) is from an article about the Balkan War, but it is often interpreted as a competitive challenge to Braque, referring to the use of papier collé . In that reading, this work is a direct response to, and attempt to one-up, Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass .

The truncated masthead of the newspaper “LE JOU” (short for le journal , French for “the newspaper”) is also meaningful. It appears in many Cubist works and not only signifies the newspaper’s presence in the still life, but also a pun on the French words for “to play” ( jouer ) and “toy” ( le jouet ). This is a verbal echo of the many formal rhymes and visual puns that appear in Synthetic Cubist works. These allow for multiple readings of individual elements and the relationships between them.

In Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass , for example, “LE JOU” also recalls the French word for day ( le jour ), and suggests another reading for the forms in the work. The circle of white paper overlapping the trapezoid of blue paper above it can be interpreted as representing not only a guitar’s sound hole and neck, but as the sun rising into the sky at the beginning of a new day. Battles often begin at dawn, and the paired juxtaposition of the papier collé guitar and the Analytic Cubist drawing of a glass suggests a competition between older and newer Cubist techniques.

Political references

Most early discussions of Cubist collages stressed their formal innovations and the novel representational strategies they employed. More recently, however, some art historians have looked more closely at the texts of the newspaper clippings in Picasso’s works and discovered references to his political interests.

Still Life with Bottle of Suze is another work that uses legible clippings of articles about the contemporary Balkan war. This one also includes a clipping about a socialist demonstration against that war held in a Paris suburb. When asked about it years later Picasso said he used that particular clipping because it was a huge event and to show that he was against the war.

While it is unlikely that Picasso expected viewers to carefully read the fine print text in the newspaper clippings he used, headlines and sub-headers often stand out and appear to make relevant comments. In Still Life with Bottle of Suze a bold face sub-header on the left, “La Dislocation”, is easily legible and placed next to the still-life objects that have been separated and dislocated by Cubist representational techniques.

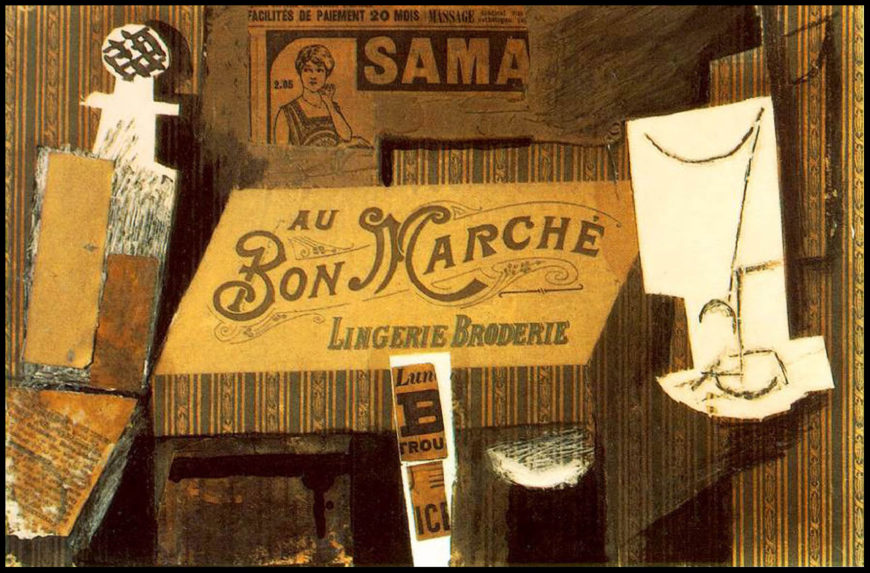

An art of ordinary activities and cheap materials

Most early Cubist collages depict still-life subjects, usually the types of objects found on café tables. They represent the ordinary places where the artists would have a drink, listen to a musical act, read a newspaper, and meet their friends. Newspaper clippings represent the sort of topical events discussed in cafés. Preserved in the artworks, the newspapers and other ordinary non-art materials such as wallpaper, labels, tickets, etc. now seem like mementos of a specific time and place.

In their collages Picasso and Braque avoided conventional, often expensive, art materials and overt displays of technical skill that would indicate artistic training. Prior to its use by Braque and Picasso, collage was primarily a craft technique used by women and hobbyists in the 19th century to make scrapbooks. Collages are “poor” art works that do not employ the professional artist’s traditional manual skills.

Picasso’s Au Bon Marché proclaims its cheapness not only in its materials, but by its title as well. Bon marché is a French term meaning “good deal” or “cheap” as well as being the name of a prominent Paris department store. At the top of the collage, an advertisement for a rival Paris department store, Samaritaine, suggests another persistent theme of the collages: references to brand name products, mass media, advertisements, and commerce. Many artists, starting with the Dadaists during World War I and continuing to the present day, adopted the Cubists’ use of cheap found materials, employing them as a critical strategy to question the commercial values of the art world and modern society.

An enormous influence

For many people the appeal of early Cubist collage and papier collé is more intellectual than conventionally aesthetic. These works prompt the viewer to enjoy the multiple references and significations to be found in the combinations of forms and punning texts, rather than displaying the sensuous qualities of the painted surface or the artist’s skilled touch.

Despite its somewhat arcane intellectual appeal, however, Cubist collage had an enormous influence on modern art in the 20th century. Its employment of simplified planar forms was instrumental in the establishment of non-representational art, especially the geometric abstraction of movements such as Suprematism , Constructivism , De Stijl , Color Field painting , and Minimalism . And, the way the collages combine disparate found materials, refer to mass consumer culture, and collapse distinctions between ‘low’ and ‘high’ culture contributed to the development of Dada, Surrealism , assemblage, Pop art , and the various trends associated with post-modernism .

Still Life with Bottle of Suze at the Kemper Art Museum

Salon Cubism

The face of cubism.

Today, most people associate Cubism with Picasso and Braque , but in the early 1910s when the style was new, the works of many other Cubist artists, including Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, and Fernand Léger, were better known. These artists are often called the Salon Cubists because they participated in the large annual public exhibitions in Paris known as Salons. Picasso and Braque, by contrast, had an exclusive contract with their dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and only showed their Cubist works in Paris at his private gallery.

The Salon Cubists lived and worked in Paris neighborhoods, mostly Montparnasse and suburban Puteaux, some distance from Picasso and Braque’s studios in Montmartre. They met frequently with writers and intellectuals to discuss a range of ideas including mathematics, physics, politics, and philosophy. The group was large; thirty artists exhibited over 200 works at their 1912 exhibition, La Section d’Or (The Golden Section). In the early 1910s their works appeared in modern art exhibitions throughout Europe.

A public profile

The Salon Cubists cultivated publicity; they showed their works as a group in order to attract attention in the overcrowded Salons. The Cubist Room at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants gained them public notice from purportedly scandalized viewers along with extensive critical recognition in newspapers and magazines.

By the time Cubism appeared, public outrage over modern art was a cliché. A long succession of modern art movements had led the public to expect incomprehensible new art works, and in the 1910s the number of “-isms” began to proliferate exponentially in both visual arts and literature. Cubism was one of the most prominent and successful movements claiming to represent the modern world in new, specifically modern ways. How it did so was, however, a matter of constant debate.

Big, ambitious paintings

Like Picasso and Braque, the Salon Cubists extended Cézanne’s exploration of the tensions and ambiguities of depicting three-dimensional objects in space on the flat surface of the picture plane. Salon Cubist paintings were, however, notably different from Picasso’s and Braque’s.

The first difference is scale. Many Salon Cubist paintings were large. Henri Le Fauconnier’s Abundance , which was considered an important example of Cubist painting and exhibited widely throughout Europe in the 1910s, measures slightly over six by four feet. Picasso’s and Braque’s contemporary Cubist works were rarely more than a quarter that size, and often much smaller.

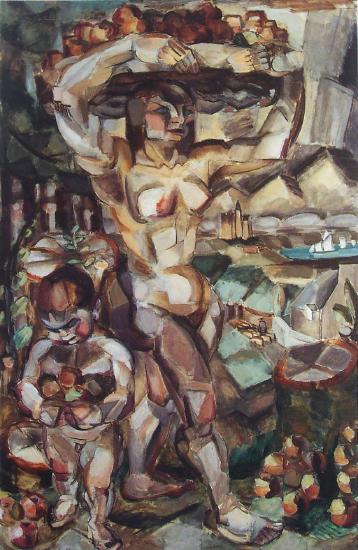

Another difference is subject matter. Picasso and Braque painted mostly still lifes and single figures in portrait format, while the Salon Cubists addressed grand themes and painted multi-figure compositions, landscapes, and cityscapes. Albert Gleizes’ The Bathers combines a pastoral scene of nude figures bathing in the foreground with the factory chimneys of a modern suburb smoking in the background. In Le Fauconnier’s Abundance an allegorical female nude and a child are surrounded by fruit symbolizing the fertility of the land, and by extension, nationalistic pride in France itself.

Conflicting interpretations

While Picasso and Braque never provided any explanation of their Cubist work, some Salon Cubists were more forthcoming. Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger published Du Cubisme (1912), which, despite its often vague and theoretically inconsistent text, was the most popular book on Cubist art for years. It was one of many texts on Cubism by critics, writers, and theorists eager to explain the new style.

Interpretations were often in conflict as critics attempted to explain how and why Cubist painters developed their non-naturalistic techniques of representation in relation to almost every scientific discovery and philosophical theory popular in the early 20th century. Some prominent critics and theorists analyzed Cubism as an art of conception (depicting what is known) rather than perception (depicting what is seen) in terms of the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. Cubist approaches to depicting figures and space were also frequently linked to non-Euclidean geometry and conceptions of space and time derived from both occultism and non-Newtonian physics. Another source for Cubist innovations was seen in the enormously popular anti-rationalist philosophy of Henri Bergson.

Bergsonian Cubism

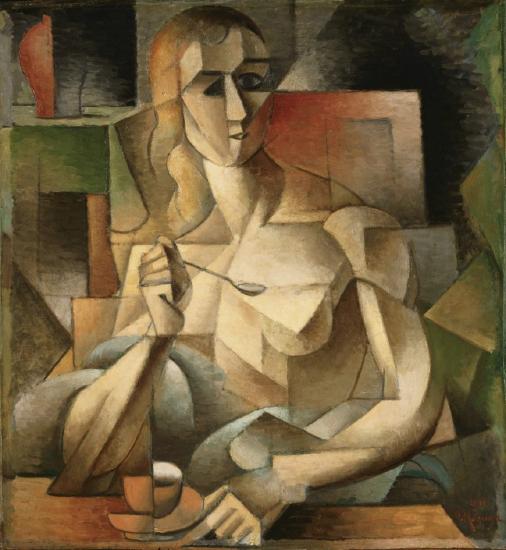

Jean Metzinger’s Le Goûter can be used to illustrate a Bergsonian approach to interpreting Cubism. The painting, whose title translates both to “taste” and “tea-time,” shows a seated woman holding a spoon and touching a tea saucer. Bergson’s philosophy stressed the importance of the physical senses, particularly touch, taste, and smell, as sources of intuitive knowledge. Le Goûter is all about sensory experience. Its female subject is partially nude, traditionally intended to appeal to the (implied) heterosexual male viewer’s sense of touch as well as sight, and it depicts her using her own senses, touching the tea saucer while smelling and tasting her tea.

Typical Cubist techniques can also be interpreted in Bergsonian terms. In Le Goûter the woman’s head and the cup are depicted from different angles. We see the cup and saucer from the side on the left and from above on the right. The woman faces us directly on the right, and is in profile on the left. According to Bergson the world is not composed of static objects isolated in empty space. Instead everything exists in duration — a continuous flow of time and space. The Cubist technique of depicting things simultaneously from different vantage points can be understood as presenting a Bergsonian conception of reality by rejecting a static single view point and showing the object as constantly changing in the temporal and spatial flux. This is also indicated by the technique of passage , breaking the boundaries between solid objects and surrounding space, as Gleizes does on the woman’s left shoulder in Le Goûter .

Bergson’s concepts of intuition and élan vital can also be used to interpret Cubism. Élan vital is Bergson’s concept of a universal life force. In Le Fauconnier’s Abundance the vibrant and chaotic interlocking planes unify the figures, fruit, village and distant Alpine landscape into a visually active, faceted surface that suggests a vital force pulsating through everything. Élan vital cannot be directly perceived or even rationally understood, but it can be intuited. Bergson believed artists were particularly sensitive and intuitive beings in tune with the élan vital , and in their art they communicated their insights to the masses.

Products of the artist’s intuitive understanding, Cubist paintings with their non-rational spaces and ambiguous forms also prompted viewers to use their own intuition to complete the images in their minds. Gleizes’ The Path (Meudon) is a patchwork of geometric shapes that on examination reveals a scene of trees towering over a suburban village with a man walking in the foreground and a church on the horizon. The dynamic interlocking planes convey both a sense of movement and of unity, a world in which each part is connected to the whole in a vibrant, oscillating pattern suggestive of the vital force that animates the Bergsonian universe.

A kaleidoscope of modern experience

Some painters used Cubist forms to suggest a more abstract and extended interpenetration of space and time than Metzinger depicted in Le Goûter .

Fernand Léger’s The Wedding combines fragmented images of a crowded wedding celebration with aerial views of rooftops and a tree-lined street, interspersed with cloudy white abstract planes. His multiple views are more complex and disjointed than the comparatively legible scenes by Gleizes, Metzinger, and Le Fauconnier.

Léger’s painting suggests floating fragments of memory brought together in a kaleidoscope of shifting images. This conflation of different scenes in a single painting can be connected to Bergson’s notion of duration and to the related concept of simultaneity, which was understood by many artists of the time as a synthesis of memory and vision.

Ultimately, the work of the Cubist artists exhibiting in the Paris Salons was no more the product of a single unified theory than were the less public Cubist works of Picasso and Braque. The Salon Cubists used the new style to address a broad range of subjects and ideas, from traditional allegories and the celebration of nature to contemporary concepts of time and space.

View a digitized copy of Du Cubisme at MoMA

Pablo Picasso

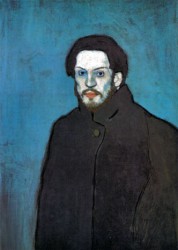

Picasso’s early work, age twenty and looking rather goth.

When I’m in the galleries at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, I obviously spend a good deal of time looking at the art. But I also watch people look at the art and listen to what they have to say. The comments that people make can be quite thoughtful and visitor comments and questions have added enormously to my appreciation of the art over the years. Still, there are many comments that are born of pure befuddlement. And many of these target Picasso.

Many people seem to believe that Picasso’s abstraction of the human figure, his penchant for reconfiguring the body by mis-aligning a nose or an eye, for instance, is the result of his inability to draw. Nothing could be farther from the truth. There is an old anecdote that tells of Picasso, who, upon emerging from an exhibition of drawings by young children, says, “When I was their age I could draw like Raphael, but it took me a lifetime to learn to draw like them.”

Perhaps this quote is apocryphal, but it points to something undeniably true: Picasso was an extraordinary craftsman, even when measured against the old masters. That he chose to struggle to overcome his visual heritage in order to find a language more responsive to the modern world is an important triumph that has had a vast effect upon our world. Picasso’s art has transformed and inspired not only artists, but also architects, designers, writers, mathematicians, and even philosophers. We may look at Picasso’s art in museums, but his art—via these translators—has therefore had a profound influence on what we see in our everyday life. Just think of the advertisements for products we buy, buildings in which we live and work, books we read, and even the way we conceive of reality.

“My kid could make that”

There is no question that Picasso’s art has had a most profound impact on the twentieth century. While Picasso suggests the value of unlearning the academic tradition, it is important to remember that he had mastered its techniques by a very early age. His father, Don José Ruiz Blasco, was a drawing teacher and curator at a small museum. The young Picasso began drawing and painting by age seven or eight. By age ten, Picasso assisted his father, sometimes painting the minor elements of the elder’s canvases. Soon after his father became a professor at the art academy in Barcelona, the young Picasso completed the entrance examinations (in record time) and was advanced to the school’s upper-level program. He repeated this feat when he applied to the Royal Academy in Madrid.

Picasso in Paris

Like Van Gogh had done before him, Picasso arrived in Paris determined to work through the avant-garde’s techniques and subjects to better understand such art. An example of his explorations of the achievements of contemporary art in Paris can be seen by comparing a painting by Degas to one by Picasso.