Bringing Schools into the 21st Century pp 137–157 Cite as

Integrating 21st Century Skills into the Curriculum

- Dianne M. Gut 3

- First Online: 27 December 2010

3417 Accesses

17 Citations

Part of the book series: Explorations of Educational Purpose ((EXEP,volume 13))

This chapter stresses the importance of imbedding 21st century skills within content area instruction. It provides a review of the 21st century skills that have been incorporated into lessons created by preservice and inservice teachers, as well as specific recommendations and resources for P–12 educators that can be utilized to incorporate the teaching of 21st century skills as identified by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills (P21) into content area lessons. Focus is on integrating in existing curriculum the instruction of 21st century content and themes (global awareness, financial, economic, business, entrepreneurial, and civic literacy, and health and wellness); learning and thinking skills (critical-thinking and problem-solving, communication and collaboration, and creativity and innovation); information, media and technology skills (information literacy, media literacy, and ICT literacy); and life and career skills (flexibility and adaptability, initiative and self-direction, social and cross-cultural interaction, productivity and accountability, and leadership and responsibility).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Banathy, B. H. (1991). Educational systems design: A journey to create the future . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Google Scholar

Boss, S. (2009). High tech reflection strategies make learning stick . Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/student-reflection-blogs-journals-technology

Cookson, P. W., Jr. (2009). What would Socrates say?. Educational Leadership , 67 (1), 8–14.

Cuban, L., Kirkpatrick, H., & Peck, C. (2001). High access and low use of technologies in high school classrooms: Explaining an apparent paradox. American Educational Research Journal , 38 (4), 813–834.

Article Google Scholar

Cutshall, S. (2009). Clicking across cultures. Educational Leadership , 67 (1), 40–44.

Fisch, K., McLeod, S., & Brenman, J. (2008). Did you know? 3.0 . Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpEnFwiqdx8

Friedman, T. L. (2005). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Helm, J. H., Turckes, S., & Hinton, K. (2010). A habitat for 21st century learning. Educational Leadership, 67 (7), 66–69.

Knobel, M., & Wilber, D. (2009). Let’s talk 2.0. Educational Leadership , 66 (6), 20–24.

Law, N., Lee, Y., & Chow, A. (2002). Practice characteristics that lead to 21st century learning outcomes. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning , 18 , 415–426.

Lee, S., Bartolic, S., & Vandewater, E. A. (2009). Predicting children’s media use in the USA: Differences in cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27 , 123–143.

Lichtenberg, J., Woock, C., & Wright, M. (2008). Ready to innovate: Are educators and executives aligned on the creative readiness of the U.S. workforce? (Report No. R-1424-08-KF). New York: The Conference Board, Americans for the Arts, American Association of School Administrators.

Ohio Resource Center. (2010). About ORC: Ohio resource center types . Retrieved from http://www.ohiorc.org/browse/resource_types/

Ohler, J. (2009). Orchestrating the media collage. Educational Leadership , 66 (6), 8–13.

Partnership for 21st Century Skills. (2004). Learning for the 21st century: A report and MILE guide for 21st century skills . Author. Retrieved from http://www.p21.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=29&Itemid=42

Partnership for 21st Century Skills. (2007). Beyond the three Rs: Voter attitudes toward 21st century skills . Author. Retrieved from http://www.p21.org/documents/P21_pollreport_singlepg.pdf

Pena, A., Lam, A., & Adiele, F. (2007). My journey home and media literacy . Washington, DC: PBS. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/weta/myjourneyhome/teachers/literacy.html

Peters, L. (2009, October 21). The rise of the globally connected student: Networks such as iEARN and ePALS are facilitating youth-to-youth exchanges and breaking down cultural barriers worldwide. eSchool News . Retrieved from http://www.eschoolnews.com/2009/10/21/the-rise-of-the-globally-connected-student/?ast=30

Ravitch, D. (2009a, September 15). Critical thinking? You need knowledge . Boston Globe. Retrieved from http://www.boston.com/

Ravitch, D. (2009b, October 10). 21st century skills: An old familiar song . Retrieved from http://www.projo.com/opinion/contributors/content/CT_ravitch10_10-10-09_LDFO9TM_v10.3f8ee5e.html

Reigeluth, C. M., Carr-Chellman, A., Beabout, B., & Watson, W. (2009). Creating shared visions of the future for K-12 education: A systematic transformation process for a learner-centered paradigm. In: L. Moller & J. B. Huett (Eds.), Learning and instructional technologies for the 21st century: Visions of the future (pp. 131–149). New York: Springer .

Robinson, K. S. (2009). Why creativity now? A conversation with Sir Ken Robinson. Educational Leadership, 67 (1), 22–26.

Schlechty, P. C. (1990). Schools for the 21st century: Leadership imperatives for educational reform . San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schlechty, P. C. (1997). Inventing better schools: An action plan for educational reform . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills. (1991). What work requires of schools: Article I. A SCANS report for America, 2000 . U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved from Article II. http://wdr.doleta.gov/SCANS/whatwork/whatwork.pdf

Small, G., & Vorgan, G. (2008). iBrain . NewYork: Collins Living.

Spira, J. B., & Goldes, D. (2007). Information overload: We have met the enemy and he is us . New York: Basex.

Sprenger, M. (2009). Focusing the digital brain. Educational Leadership , 67 (1), 34–39.

University of California Berkley School of Information Management Systems. (2003). How much information? 2003 . Berkley, CA: Author. Retrieved from http://www2.sims.berkeley.edu/research/projects/how-much-info-2003/printable_report.pdf

Wagner, T. (2008). Rigor redefined. Educational Leadership , 66 (2), 20–24.

Wallis, C. (2006, December 10). How to bring our schools out of the 20th century. Time Magazine . Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1568480,00.htm

Walser, N. (2008, September/October). Teaching 21st century skills. Harvard Education Letter, 24 (5). Retrieved from http://www.hepg.org/hel/article/184

Wan, G. (2006). Integrating media literacy into the curriculum. Academic Exchange Quarterly , 10 (3), 174.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Patton College of Education and Human Services, Ohio University, Athens, OH, 45701, USA

Dianne M. Gut

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dianne M. Gut .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

College of Education, Ohio University, McCracken Hall, Athens, 45701-2979, Ohio, USA

Guofang Wan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Gut, D.M. (2011). Integrating 21st Century Skills into the Curriculum. In: Wan, G., Gut, D. (eds) Bringing Schools into the 21st Century. Explorations of Educational Purpose, vol 13. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0268-4_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0268-4_7

Published : 27 December 2010

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-0267-7

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-0268-4

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Our Mission

Why Integrate?: A Case for Collating the Curriculum

There is a strong case to be made for integrating curriculum. It strengthens skills that students encounter in one content area but also practice in another, and it can lead to the mastery of those skills. It is also a more authentic way of learning because it reflects what we experience, both professionally and personally, in the world.And it can be a way to engage students who might otherwise check out when we introduce them to a challenging subject or to one they don't feel is relevant.

Sometimes, if you're really lucky, integrating curriculum can create the conditions in which students discover their passions. They find something they love doing so much that it compels them to persevere through all kinds of personal and academic challenges, to graduate from high school, and to go to college to pursue their dreams. And in the part of Oakland, California, where I work, this achievement often constitutes saving a life.

So when I think about making a case for interdisciplinary studies, I think immediately of George. (All student names in this post are pseudonyms.) I wonder what would have happened to him had Keiko Suda not put a video camera in his hands in seventh grade.

The Curriculum

Keiko Suda was George's seventh-grade math and science teacher. She was charged with teaching cell biology as part of California's seventh-grade standards. At the ASCEND School , where Suda and I taught together, teachers were encouraged to develop curricular units that emphasized depth over breadth and to teach our students how to transfer their acquired knowledge to other contexts. (See this Edutopia.org article and this Edutopia video about the school.)

Suda designed a semester-long study of HIV/AIDS with the guiding question "How does HIV/AIDS affect us physically and socially?" Students learned about the immune system and cell biology and explored what it means to live with HIV/AIDS.

As a culminating project, students wrote, directed, produced, edited, and starred in a movie that answered their guiding question. One class focused on the social implications of living with HIV, while the other class depicted what happens to the immune system.

Evidence of Learning

A skillful teacher must assess an instructional unit while it is under way and afterward, and the evaluation must be based on evidence of learning. Suda's formative and summative assessments provided overwhelming evidence that students had mastered the science standards. This finding, however, was just the beginning.

During that semester, I witnessed students transferring their knowledge of HIV. In the portable classroom next to Suda's, I taught history and English to the same group of students. Our content for that semester was the bubonic plague, and students explored how the plague transformed the social, economic, political, and religious structures of medieval Europe.

When we began the study, a few weeks or so after they'd started studying HIV, one of the first questions from a student was, "Who was scapegoated during the plague?" Based on her understanding of what some HIV-positive people have faced, she predicted that the same experience might have occurred during another epidemic -- and she was right. This was powerful evidence of deep learning.

The culminating project in my class was a dramatic performance. As students applied the concepts they'd learned with Suda to their understanding of the plague, they also practiced and perfected scriptwriting and acting skills for this project.

I credit my own deeper understanding of viruses to the movies students created with Suda. It took Nestor's frightening portrayal of an HIV cell to permanently etch into my mind how HIV operates. In One Strike, he hovers menacingly over the bound and immobilized immune system cell and declares, "You're going to be my host. I will enter you and hijack your nucleus." This statement permanently stuck to some receptor in my brain, whereas before, I had never been able to retain the same information when it was delivered in print.

More evidence of deep learning became apparent once our students had graduated from the ASCEND School and had gone off to high school. In ninth grade, Maria wrote a poem about a young woman who contracts HIV. Her moving poem, one of thousands of entries, won an award in a contest sponsored by author Alice Walker.

Finding One's Footing Through Film

But it is George who comes to mind as overwhelmingly compelling evidence of the power of integrating curriculum. For George, the experience of making a movie for Keiko Suda's class was his first taste of filmmaking. From that moment, he was hooked. Fortunately, he attended an Oakland high school where he received tremendous support to pursue his passion. Over his four years there, he made three movies, taught other students in a filmmaking class, and wrote a guide to filmmaking.

During those years, George also experienced a series of traumatic personal losses. There were numerous times when he told me he just wanted to give up, particularly as he watched many of his cousins and peers drop out of school, join gangs, and have babies. What kept him going, he said, was his desire to be a filmmaker.

In June 2008, George graduated from high school. This fall, he is attending the University of California at Santa Barbara, where he will study filmmaking. At his high school graduation, he spoke of his intention to become a director. His father, an immigrant, wept while watching his only son graduate.

"How do you feel about his decision to study film?" I asked George's father.

He shrugged and responded, "He's discovered his passion. I'm happy for him. What more could a father want?"

As a result of Keiko Suda's brilliant interdisciplinary study, George, who didn't like science, mastered seventh-grade cell-biology standards, strengthened his writing, developed social and interpersonal skills, and discovered a lifelong passion that propelled him through high school and on to higher education.

And that's just one story. Stick around. There will be more.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Equipping teachers with globally competent practices: A mixed methods study on integrating global competence and teacher education

Shea n. kerkhoff.

a Department of Educator Preparation and Leadership, College of Education, University of Missouri – St. Louis, 1 University Blvd., St. Louis, MO, 63122, USA

Megan E. Cloud

b College of Education, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA

Associated Data

- • The Global Teaching Model is situated locally, integrated with standards, critical framing, and intercultural collaboration.

- • Our data showed that global education was not a part of participants’ current curriculum.

- • However, teachers believed that global competence was important for them and their students.

- • Our findings show that teachers need guidance in translating global education theory to practice.

Education leaders recommend that global competence–global citizenship mentality and knowledge development for global participation–be incorporated into school curricula. This mixed methods study examined teacher’s perceptions and self-reported practices of globally competent teaching. Data was collected from teachers taking a graduate education course infused with global learning. Results suggest teachers value and desire to enact globally competent teaching but need practical direction for classroom effectuation. Data manifest all four dimensions of the Global Teaching Model (i.e., situated relevant practice, integrated global learning, critical and cultural consciousness raising, and intercultural collaboration for transformative action) to differing degrees. This study provides evidence for the Global Teaching Model as a prospective framework and emphasizes the critical dimension when internationalizing teacher education.

1. Introduction

Today’s world is increasingly interconnected, and growth in global migration has led to more diversity in schools worldwide ( Suárez-Orozco, 2001 ). The authors’ home is no exception to this international trend. In Missouri the number of foreign-born residents increased 51 percent from 2000 to 2010 ( Asia Society, 2018 ) and our hometown of St. Louis led the nation in immigrant population growth in 2016 ( Hulsey, 2016 ; US Census, 2017 ).

Education leaders have called for students to develop global competence for our interconnected world ( Rizvi & Lingard, 2009 ; OECD & Asia Society, 2018 ; US DOE, 2018 ). Longview Foundation defines global competence as “a body of knowledge about world regions, cultures, and global issues, and the skills and dispositions to engage responsibly and effectively in a global environment” ( 2008, p. 7 ). To be globally competent, students need global citizenship dispositions and the multiple literacies necessary for participation in a digital, global world ( Kerkhoff, 2017 ). In order for change to occur in education, however, the extant literature shows that teachers must be trained in teaching global competence ( Kerkhoff, Dimitrieska, Woerner, & Alsup, 2019 ; West, 2012 ; Yemini, Tibbitts, & Goren, 2019 ).

Internationalizing teacher preparation can help teachers personally develop global competence and gain the knowledge and resources necessary for teaching global competence to their K-12 students ( Longview Foundation, 2008 ; Zhao, 2010 ). Traveling abroad is one approach; however, cost makes international travel an unrealistic option for many teachers ( Parkhouse, Tichnor-Wagner, Glazier, & Cain, 2016 ) and the Coronavirus pandemic makes international travel unlikely in the foreseeable future. In this study, the authors investigate ways of internationalizing teacher education curricula that do not require travel. Primarily, the purpose of this study was to investigate teachers’ perceptions and practices related to teaching global competence after participating in the first author’s teacher education course framed with the Global Teaching Model (GTM). A secondary purpose was to examine the feasibility of the GTM, operationalized and validated in Kerkhoff (2017) , as a framework for understanding globally competent teaching.

The GTM was developed through a sequential mixed methods process beginning with in-depth interviews with 24 expert global teachers followed by factor analysis to determine if the findings that emerged from qualitative analysis were generalizable to a larger population of 630 teachers. The process yielded a 19-item Teaching for Global Readiness scale (TGRS) and the four factor GTM. The creation of the GTM was framed in critical theory focused on equity worldwide (i.e., Andreotti, 2010 ; Wahlström, 2014 ).

2. Postcolonialism: a critical lens for global teaching

For educators concerned with equity and critical pedagogy, postcolonialism offers a theoretical lens for globally competent teaching ( Masemula, 2015 ; OöConnor & Zeichner, 2011 ). Postcolonialism according to Andreotti (2010) acknowledges that current societal injustices are directly related to the history of colonization. According to Andreotti, “Our stories of reality, our knowledges, are always situated (culturally bound), partial (what one sees may not be what another sees), contingent (context dependent) and provisional (they change)” (p. 236). Her postcolonial take on global education emphasizes a non-coercive inner process where one negotiates for a broader understanding of human experiences. Postcolonialism offers plural epistemologies where multiple truths are recognized because multiple human experiences are acknowledged and valued.

Using postcolonialism as the theoretical lens, Subedi (2013) put forth three approaches to global education: deficit, accommodation, and decolonization. A deficit global curriculum maintains a strict dichotomy between “us and them.” Eurocentrism is viewed as the dominant ideology, cultural ideal, and lens through which all other cultures and peoples are viewed. In this approach, global discussions center on the problems of the non-Westernized world. The fundamental presupposition of the deficit approach is that Western values are superior and, therefore, the answer to global “problems.” When global events or cultures are presented in a deficit curriculum, they are positioned as dangerous, deviant, and “not worthy of serious academic inquiry” ( Subedi, 2013, p. 628 ).

Similarly, the accommodation global curriculum does little to counter the underlying assumptions of Western/European superiority and ignores the ways Western values acquired historical privilege and power; however, it does bring awareness of global perspectives and events into the classroom. Chosen texts expose students to diverse voices from other cultures while still upholding Western values as the norm. Although well-intentioned, the absence of critical and sociocultural awareness perpetuates stereotypes and reifies the dichotomy of the West and the rest.

Decolonizing global curriculum, however, takes a critical approach when examining the social, cultural, and political influences of knowledge production. Decolonizing is the preferred method of global learning specifically because it comes from critical (concerned with power) and resource (as opposed to deficit) frames. When studying global perspectives, decolonization seeks to read, formulate, and address “events from the perspective of marginalized subjects” ( Subedi, 2013, p. 634 ). It advocates for an anti-essentialist curriculum that dispels the notions of monolithic cultures and the justification of hierarchies due to cultural differences.

In addition to decolonizing curriculum, Ndimande (2018) calls for decolonizing research that influences education policy and practice. This research project hopes to contribute to decolonizing efforts in this field. We are aware of the limitations in reaching this goal, however, as our university affiliation implicates us in the legacy of colonialism ( Subedi, 2013 ). Though we may not be able to eliminate all bias or Western influence on our research, we aim to avoid deficit language and “us and them” conceptualizations, and accept plural epistemologies. While we acknowledge that publishing this research benefits us as authors, we hope it will primarily contribute to transformative educational practices that amplify equity and social justice in teacher education.

3. Pedagogies and models for globally competent teaching

O’Connor and Zeichner (2011) describe globally competent teaching as a practice that is simultaneously broad and specific: Broad in that it transcends disciplines and age-levels, and specific in that it should be relevant to local socio-political contexts and students’ cultural identities. In this study, we focused on global competence in teacher education. Specifically, we use Kerkhoff (2017) empirically validated Global Teaching Model (GTM) as a conceptual framework. In the following sections, we review the relevant teacher education research and then synthesize extant literature with the four dimensions of the GTM.

3.1. Curriculum and instruction in global teacher education

Research describes curricula and pedagogies of global teacher education in multidimensional ways. Some colleges of education have integrated global issues and cultures into existing curricula ( Carano, 2013 ; Ferguson-Patrick, Reynolds, & Macqueen, 2018 ; Poole & Russell, 2015 ), while others have created stand-alone global education courses ( Kerkhoff et al., 2019 ; Quezada & Cordeiro, 2016 ). Through an extensive literature review, Yemini and colleagues found that pedagogies in global teacher education research are innovative (but not necessarily new) takes on existing pedagogies ( 2019 ). Mansilla and Chua (2017) call these innovative approaches to global education “signature pedagogies.” Signature pedagogies include engaging teachers in inquiry about the world ( Kerkhoff, 2018 ), participating in intercultural dialogue ( Kopish, Shahri, & Amira, 2019 ; Ukpokodu, 2010 ; Zong, 2009 ), and playing a role in simulations with global content ( Myers & Rivero, 2019 ).

Tichnor-Wagner, Glazier, Parkhouse, and Cain undertook extensive qualitative research on signature pedagogies for globally competent teaching. They produced the Globally Competent Teaching Continuum (GCTC; 2019). The continuum signifies that globally competent teaching is a developmental progression. The continuum includes twelve components organized as knowledge, skills, or dispositions, such as the disposition of empathy and valuing multiple perspectives and the skill to facilitate intercultural and international conversations that promote active listening, critical thinking, and perspective recognition . Although all twelve components (see Table 1 ) are theoretically sound, the number of dimensions in this continuum may impede its use as a heuristic in teacher education.

Comparison of the Globally Competent Teaching Continuum Twelve Components and the Four Factors of the Global Teaching Model.

3.2. Global teaching model

Kerkhoff’s (2017) GTM is based on a mixed methods study with K-12 educators. Because global teaching is contextualized within a nation ( Fujikane, 2003 ), the model was developed for and validated specifically in the U.S. K-12 context. The GTM comprises four factors: situated, integrated, critical, and transactional. These factors served as the conceptual framework for both the course and this study, and provided teachers a heuristic for implementing global teaching. When placed side-by-side, as in Table 1 , all but one (i.e., communicate in multiple languages) of the GCTC’s twelve elements aligned with the four factors of the GTM.

GTM’s first factor is situated practice, meaning teaching is culturally relevant to both students in the class and socio-political issues in the local community. Situated practice includes the dispositions of valuing diversity and students’ voices. Situated practice is culturally relevant ( Ladson-Billings, 2004 ), helps break down stereotypes, and works against essentializing people, places, or times in history ( Apple, 2011 ; Mikander, 2016 ). Situated practice acknowledges local and global connections: Teachers stay current on local and global events and consider multiple perspectives (even those that challenge their own beliefs). Teachers also reflect on their own cultures, assumptions, and biases ( Hull & Stornaiuolo, 2014 ). Most importantly, teachers guide students in doing all of the above.

Integrated, the next GTM factor, means global learning is not a one-off but incorporated across grade levels and disciplines. Teaching and assessment of global learning are part of course objectives. Teachers build a repertoire of resources related to global issues in the discipline/s they teach. Teachers understand how the world is interconnected, and can analyze global challenges and inequities through a disciplinary lens. Integrated global learning requires students to construct knowledge about the world through authentic inquiry and experiential learning ( Choo, 2017 ). Students understand how their actions affect people in other countries and vice versa ( Mikander, 2016 ). Through situated and integrated global learning, teachers show students how both their lives and their studies are already globally interconnected.

The third dimension is critical. Global teaching through a critical frame considers issues of power, privilege, and oppression so that teaching does not recreate hierarchies found in the world ( Delpit, 2006 ; Freire, 1970 ). Critical includes the critical literacy practices of analyzing source reliability and bias, and constructing claims based on evidence from wide-ranging authors. Teachers involve multiple, international, and traditionally marginalized voices and encourage perspective-taking and empathy-building ( Pashby, 2008 ; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2019). Students listen/read first to understand different perspectives ( Freire, 1970 ) and then write/speak their perspective in ways that demonstrate intercultural and global consciousness ( Pashby, 2008 ). Part of critical framing is reflexivity, or what O’Connor and Zeichner (2011) referred to as “sociocultural consciousness,” where teachers acknowledge they are cultural and political beings and examine their biases. The development of critical literacy is one way to raise sociocultural consciousness.

Fourth, transactional experiences involve international partnerships, through which students engage in intercultural dialogue and construct knowledge about the world ( Kerkhoff, 2018 ). Transactional experiences mean learning with other people through active listening and critical thinking. It also means problem-solving with others in solidarity, rather than solving others’ problems in ways that reinforce colonial power relationships. Transaction means there is an equal give-and-take, and global teaching requires equitable partnerships with global communities ( Wahlström, 2014 ).

The first two factors, situated and integrated, describe how global teaching can be connected to existing curricular structures and instructional practices. The last two factors, critical and transactional, explain how teaching about the world can be approached from a critical frame and commitment to equity.

This article describes a mixed methods self-study of a graduate-level teacher education course called Learning through Inquiry. Self-study involves systematic analysis towards both the improvement of one’s practice and contribution to the field ( Hamilton & Pinnegar, 2000 ). Research questions were: (1) To what degree do participants report implementing global teaching practices in their K-12 classrooms? (2) How do participants understand the role of global competence? (3) According to participants, what influenced how they employed globally competent teaching? With these research questions as the hub ( Maxwell & Loomis, 2003 ), we used concurrent nested mixed methods by collecting both qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously, embedding the quantitative within the qualitative ( Creswell, Plano Clark, Gutmann, & Hanson, 2003 ).

4.1. Context

The study took place during an online masters’ level education course at a U.S. urban university. The course (Learning through Inquiry) was organized into eight modules, including modules on collaborative learning, culturally sustaining pedagogy, and global learning. Each module contained readings on education theory, discussion boards where students interacted, and assignments where students were tasked with translating theory into practice. Instructional plans for the global learning module can be found in Appendix A . The first author was the course instructor, and the second author was the research assistant.

4.2. Participants

All participants were enrolled in the university’s masters of education program. Every student in the first author’s course was invited to participate; 19 consented to analysis of their coursework and four agreed to follow-up interviews. Consent was also obtained from 56 students (focal group = 28, comparison group = 28) for anonymous completion of the Teaching for Global Readiness Scale (TGRS). The focal group consisted of students in the first author’s course, and the comparison group (recruited from a separate online masters education course) consisted of students with no known prior exposure to globally-focused teaching curriculum.

The focus course served both the masters in curriculum and instruction degree and the alternative teaching certification program, so at the time of the study, all participants were inservice teachers, but not all were yet licensed. Years of teaching experience ranged from one to 18. Participants’ schools were spread across the state and spanned the spectrum of public, charter, and private, as well as rural, suburban, and urban. Five participants identified as African American, two as Asian American, one as Latinx, and 12 as white. Grades and subjects taught varied (see Table 2 ).

Profile of Focal Participants.

4.3. Data sources

Self-study requires that the researcher/teacher provides convincing evidence ( Hamilton & Pinnegar, 2000 ). In order to provide copious evidence, we utilized both qualitative and quantitative data sources. Focal group participants contributed both qualitative and quantitative data; quantitative data alone were collected from the control group ( Table 3 ).

Table of data collection.

Qualitative data were collected via course artifacts, i.e., discussions, self-reflections, and lesson plans from the global learning module in Canvas. Students completed lesson plans and personal inquiry projects on topics related to global education and wrote reflections upon completion of each. Focal participants completed the TGRS at the beginning and end of the semester and reflected on their growth, facilitating self-reflection on TGRS-related teaching practices during their qualitative interviews.

One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with four participants the semester following the course. Due to the participants’ geographic spread, interviews were conducted face-to-face when possible and using Zoom when not. All were recorded and transcribed. The protocol can be found in Appendix B .

Quantitative data were collected anonymously via a knowledge inventory and the TGRS. The knowledge inventory measured participants’ self-reported knowledge level of concepts covered in the course, including the concept of global learning. The survey comprised 21 questions adapted from TGRS, which measures teachers’ attitudes about and frequency of teaching practices that promote global readiness. The original scale ( Kerkhoff, 2017 ) was found to be a reliable and valid measure of global teaching (χ 2 (143) 246.909, χ 2 to df = 1.73, CFI = 0.960, TLI = 0.953, SRMR = 0.061, RMSEA = 0.051, α = 0.88). Cronbach’s alpha showed good reliability of the adapted TGRS ( α = .89). A list of scale items can be found in Table 4 .

Group Means by Teaching for Global Readiness Scale Item.

Note : Parentheses around subscales indicate items that have not yet been validated.

4.4. Quantitative analysis

To inform instruction, the knowledge inventory was given to participants at the beginning of the course. Descriptive data are reported to show participants’ knowledge of global learning before engaging in course material. TGRS was administered to two groups (i.e., focal and control). Group means from individual scale items were analyzed using two-sample independent t -tests. The TGRS was anonymous in order to mitigate instructor’s influence and promote honest self-reflection. Because the TGRS was anonymous, we could not conduct a paired t -test or compare individual’s pre and post tests; instead, we utilized a two-sample independent t -test to compare post result means against a control group. To contribute to validating and operationalizing the GTM model, TGRS post-course responses were then quantitatively compared between the focal and control groups.

4.5. Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data sources were analyzed using a priori and open coding. For a priori coding, we used the GTM four factors, paying particular attention to statistically significant items from quantitative analysis (i.e., using texts written by authors from diverse countries , guided students to examine their cultural identity , constructed claims based on primary sources , and built a repertoire of resources related to global education ).

After coding individually, we met to discuss and reach consensus about coding parameters. We ultimately agreed valuable data were not captured solely by a priori codes; therefore, the next round included a priori as well as open coding. We determined that a hierarchical process was most appropriate for the next step. We converted the four a priori codes into themes and placed related codes under each theme looking for patterns within to create categorical codes.

Within each code, we looked for illustrative key statements (i.e., participant quotes in the data) that answered the research questions. Codes were triangulated by looking at multiple data sources and multiple participants ( Yin, 2014 ). Counter examples were also coded to increase trustworthiness of the findings.

4.6. Ethical considerations

Given that the first author was also the course instructor, we took great care to conduct research in an ethical manner. Institutional Review Board approved protocols were followed for all aspects, including gaining participant consent. Surveys were completed anonymously and, as such, not graded. In addition, one-on-one interviews took place after grades were submitted. These methods were enacted to protect the participants; yet we acknowledge these data cannot be separated from a contextual power difference between the researcher (as professor) and the participants (as her students). It is possible that participants reported what they believed the professor wanted to hear rather than their honest perceptions.

5. Findings

We sought to investigate three research questions: (1) How frequently do participants report implementing global teaching practices in their K-12 classrooms? (2) How do participants perceive the role of global competence? (3) According to participants, what influenced how they enacted globally competent teaching? Quantitative results addressed RQ1 and are reported first, followed by qualitative findings concerning RQ2 and 3.

5.1. Quantitative results

Quantitative results were derived by statistical analyses of data from both the knowledge inventory and TGRS.

5.2. Knowledge inventory

At the beginning of the course, participants complete a knowledge inventory on instructional concepts. Using Google forms, we gave the following instructions: On a scale of 1–5, how well do you know the following instructional concepts? For the item on global learning, only one participant believed that global learning was a current part of their instructional repertoire ( Fig. 1 ).

Participant responses to the knowledge inventory item on global learning.

5.3. Teaching for global readiness scale

Descriptive data are reported in Table 4 . Participants responded to 21 statements. The first 16 inquired about frequency of implementation over the past two weeks using a 1–5 scale (i.e., Never, Once in two weeks, Once a week, 2–3 times a week, Daily ), and five addressed attitudes about practices across a typical semester (i.e., Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Agree, Strongly agree ).

Focal participants (i.e. teachers exposed to global competence via their graduate teaching course) reported implementing 81 % of TGRS practices more than once over two weeks (control group: 56 %), with statistically significant greater frequency in these specific practices: (a) Using texts written by global authors ( M = 2.68, SD = 1.12; M = 1.86, SD = 1.13; p = .0142); (b) Guiding students to examine their cultural identities ( M = 3.32, SD = 1.12; M = 2.43, SD = 1.50; p = .0197); and (c) Asking students to construct claims based on primary sources ( M = 2.68, SD = 1.25; M = 1.96, SD = 1.22; p = .0434). When reporting on five additional practices used over a typical semester, significant difference was seen between group attitudes on the following item: Focal teachers believed they “[built] a repertoire of global-education resources” more strongly than control teachers ( M = 3.32, SD = 1.02; M = 2.43, SD = 1.31; p = .009). Of the four subscales, significant difference was seen within situated, integrated, and critical, but not within the transactional subscale.

5.4. Qualitative findings

Our qualitative analysis focused on patterns across participants. Key statements that illustrate those patterns are described below, organized around the four dimensions of the GTM (situated practice, integrated global learning, critical framing, and transactional experiences), and followed by challenges related to global teaching that participants perceived.

5.4.1. Situated practice

The factor of situated practice was a frequently coded theme. Under this theme, we noticed two categorical codes: cultivating students’ cultural identity and expanding the definition of relevance.

5.4.1.1. Cultivating students’ cultural identity

Cultivating cultural identity begins with understanding that teaching and learning are cultural practices. Teachers understand themselves to be cultural beings and help students to build the same understanding. For example, after studying the global module, a science teacher created an enduring understanding for a lesson plan: “Students are aware of how differing cultural contexts may affect how a certain mutation can be viewed in society as beneficial or harmful.” This understanding went beyond scientific knowledge of mutations to an understanding of how culture shapes one’s perceptions of scientific concepts. This particular lesson plan involved readings on congenital twins in India and the U.S. and, based on the news reporting, having students consider cultural assumptions regarding the mutation (i.e., beneficial, neutral, or harmful?).

Another participant mentioned she had taken for granted that students would develop cultural identities outside of school. Before the course, she had not utilized reading and writing to support the positive development of her students’ cultural identities. She said:

My classroom is full of diverse learners who speak different languages and come from different cultures. Through this course, the importance of embracing students' cultural identity has become clearer. Before, I was guilty of believing that their cultural identity was examined on their own. However, I am now understanding that a teacher can have a crucial role in encouraging students to celebrate their own and their classmates’ cultural identities.

A different participant noted that, although they had discussed culture in class, they had not connected discussions to their students’ cultural identities. This participant felt that learning about students’ cultures, and linking teaching to those cultures, helped them better connect.

Every unit, my students are analyzing primary and secondary sources from people all around the world. But this course made me think more about my students’ cultures. I am able to communicate better with students from other cultures because I am more aware of it. I never thought about how that could affect a student until now.

Overall, participants perceived the connection to their students’ cultural identities as an important component of global teaching. In addition, participants expanded their capacity to make connections in the classroom by connecting cultures outside of U.S. subcultures and connecting current issues.

5.4.1.2. Expanded definition of relevance

Participants studied culturally sustaining pedagogy during a course module. Our readings addressed diverse racial and ethnic identities within the U.S. While studying global learning, participants expanded their definition of cultural relevance to include the intersection of national, racial, and ethnic identities‒–for example, exposing students to black scientists from the U.S., Brazil, and Nigeria. A science teacher commented:

My students enjoy reading about scientists that look or come from places like them, but it would also be special to hear about other scientists that might not share as obvious similarities. My students are comfortable sharing their experiences and perspectives, so to take their global consciousness to the next level, they would benefit from more global lessons.

In his reflection about TGRS, a different science teacher shared his desire to move his teaching away from a Western-centric education in order to better serve his diverse students.

Participants also expanded their definition of relevance to include timeliness. In a discussion board, an English teacher remarked how two teachers found their students enjoyed studying international current events: “I think we often forget that relatable instruction does not have to be about what is going on in our specific communities, but what is going on in the world.” In this way, international current events became relevant because of the time aspect. Students connected to the events because they were happening now.

As mentioned above, participants reported embracing culturally relevant pedagogy before taking the course but found the expansion of social justice to global issues a welcomed addition. One participant immediately implemented a strategy from the course: She began pairing current events with perspective-taking discussion protocols (e.g., this issue matters to me because , to my friends and family because , and to the world because ) in her classroom. She believed perspective-taking was an important component of critical literacy, and using international current events expanded students’ critical analysis to include global viewpoints. A different teacher self-reflected:

I am constantly thinking about how I can empower students to be agents of change within their community. This module has me thinking about the need for my students to widen their perspective even more in order to include the entire world in their thoughts.

Designing situated practice inclusive of global cultures and international current events was a pattern noticed across grade levels and content areas. Participants perceived that situated practice and global learning could be integrated with their current responsibilities, as described in the next section.

5.4.2. Integrating global learning

At the beginning of the semester, all but one teacher reported that their curricula did not integrate global learning. However, participants came to the course believing that global learning was important, were easily persuaded of its importance, or, at the very least, did not actively resist the idea. As a representation of what most participants shared in the discussion post about global competence, a high school teacher stated: “It is important for them to learn how to inquire about the world, understand cultural and global perspectives, and most importantly interact with their world in a respectful way.” Overall, patterns related to integrated global learning included three codes: navigating tensions, focus teacher education on “the how,” and infusion with current pedagogies.

5.4.2.1. Navigating tensions

At the end of the course, a science teacher shared his perception of the tension between the local and the global: “The heavy focus we get on culturally relevant pedagogy, we have been groomed to prioritize locality, and we still should…but our students need to also see and experience beyond because that is what the world will demand of them as they exit high school and continue into universities, trade schools, and the workforce.”

In addition to the tension between local and global, participants also discussed tension between tested and not-tested content. A charter school beginning teacher articulated the pressure she felt to focus on tests. In response to a peer who was able to integrate global literature because she could choose what her students read, this teacher posted the following:

I certainly understand global readiness and can articulate its value, but I'm actually supportive of my district’s control over what is taught. My students achieve higher than their counterparts. ALL of my students come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and I don't think that as a privileged white lady, I should be deciding what my students "need". I think global learning is AWESOME, but I'm not able to implement it any time soon. (capitalization in original)

In response to the same discussion thread, another beginning teacher replied:

Implementing global readiness into my science curriculum is going to be quite challenging—given the breadth of topics I need to cover before End-Of-Course testing. Regardless, if I do so intentionally, I can get students to expand their depth of content knowledge to the levels they need for the questioning and reasoning that an End-of-Course exam can throw at them.

As evidenced by the two quotes, participants felt that global learning is important because of the globally interconnected nature of career, college, and community and because students come from diverse cultures; however they did not feel confident in implementing global learning due to tension with tested content.

5.4.2.2. Focus teacher education on “the how.”

Overall, participants reported that the course’s focus on how to integrate global learning was helpful. For example, a high school teacher stated: “Where I see growth is having a better understanding of HOW to implement global readiness into my classroom. I knew the theoretical importance of doing so but really didn't know exactly HOW to go about it effectively” (capitalization in original). Another participant said: “[Teachers] need to learn a framework of how to make sense of … the unfamiliar.” She perceived that a framework was needed for how to enact global teaching.

5.4.2.3. Infusion with current pedagogies

The two most common ways that participants reported uptake of global teaching were infusion with current curricular activities or with a desired pedagogy. For example, in her final project, an elementary teacher explained how she infused global learning with a webquest, a pedagogy that she had desired to bring into her practice:

Because of this course, my 5th grade science students researched natural disasters to complete a webquest that modeled how the Earth spheres interact. During that webquest, I provided my students with articles and videos about natural disasters across the world. This has helped my students learn global competence.

Since webquest was a new pedagogy she had wanted to use, it provided an opportunity to infuse global learning in the instructional design.

Another way participants reported integrating global learning was through the pedagogical practice of students’ reading texts. Incorporating diverse texts from international authors into their classes was seen across grade levels and disciplines, and as reported in the quantitative results, was significantly higher than the control group. Reflecting on the comparison between beginning and end of the semester TGRSs, one teacher said, “One major change has been the sources that I have incorporated into lessons.” A mathematics teacher reported, “I have changed how I use text and global learning within my classroom.” An English teacher said, “I grew the most in incorporating global texts and authors into my teaching.”

By the end of the semester, participants, with the exception of three math teachers, were able to create global lesson plans that infused global learning with their curricula. One math teacher wrote a lesson plan for a government course; the other two math teachers asked to complete a comparative inquiry on mathematics in other countries in an effort to build more globally connected content knowledge. As one participant stated, “I think creating a stockpile of potential global issues related to math over time could be a way to make integrating global readiness easier in future years.” She perceived that gathering global resources would help her integrate global learning in future lessons.

5.4.3. Critical framing of teaching and learning

The next theme is critical framing. Several participants embraced a decolonizing lens. For example, the science teacher mentioned previously vowed to expand his teaching beyond a Western-centric lens. More often, the critical frame was taken up via course opportunities for reflection and lesson creation. We also found that while some participants believed that they held a critical frame, their ideas on applying global learning in the classroom reflected deficit or assimilation mindsets. Two categorical codes ultimately emerged under critical framing: engaging in self-reflexivity and teaching perspective-taking and empathy-building.

5.4.3.1. Self-reflexivity

Participants demonstrated self-reflexivity when they were reflecting on their beliefs and how those beliefs affected others. The view that teachers do not know everything, and that teachers can learn from and with their students, emerged as a frequent code from the reflections data. One participant stated it was her “civic duty” to be aware of all international events, yet most participants perceived mutual teacher/student inquiry of world events to be a strength of the GTM. A special education teacher shared, “It is important to see how you fit into the equation. How your actions or lack of action impact others and how the actions of entire areas across the globe impact others.” In the discussion board, a mathematics teacher commented, “I love that you acknowledge that sometimes you lack being competent. I have also been guilty of this until … visiting Brazil and actually immersing myself in another culture. I think if people took time to investigate global issues, they would see the world in a different way.” This participant perceived her trip abroad as an integral moment in her ability to see different views and to reflect on her own cultural assumptions.

An intriguing finding was how some participants really valued reflexivity as part of teaching. An elementary teacher stated, “I do consider myself to be a pretty reflective teacher, but having an actual piece [PDF of TGRS results] I filled out two separate times was interesting.” Another teacher reflected, “I liked … the recursive reflective nature. We were constantly absorbing new material from a variety of perspectives and this helped bring these to … my mind over and over, to the extent that I actually could try to apply the ideas and could reflect.” Similarly, a different participant shared:

This class really showed me the importance of incorporating reflective practices into my pedagogy. Being a teacher means taking the time to reflect on personal biases, strengths, weaknesses and instructional methods that can be improved to meet students’ needs.

Reflection on one’s teaching and connection to other people, both in the classroom and around the world, is an important component of global teaching from a critical lens. Once teachers engage in self-reflexivity, the next step is teaching students to examine the world with a critical lens. Some participants asked their students to investigate sociopolitical global issues from a standpoint of power, but most remained at an accommodation stance by focusing their teaching on perspective-taking and empathy-building.

5.4.3.2. Teaching perspective-taking and empathy-building

Participants most commonly discussed taking up global teaching by engaging students in perspective-taking and empathy-building. In a discussion post, a few teachers lamented about the lack of empathy students displayed. One wrote: “Similar to Cecilia (pseudonym), my students take a satisfaction survey every quarter, and often most students say that they don't empathize with their peers or try to learn about their backgrounds and situations.” Another teacher in the discussion thread pushed back at the deficit views by saying:

You will be surprised how students really embrace other students’ differences when their cultural identity is exposed for something more than stereotypes. Sometimes when students are sharing a personal experience or family tradition, the other students find it interesting. This helps students get to know and accept each other. I have been doing lessons on empathy, and I have seen my students grow in this area a great deal.

This teacher taught students with social and emotional disabilities and focused her global learning lesson plan on empathy-building. As her quote above demonstrates, she perceived growth in her students. A social studies teacher said his parents from India taught him the value of perspective-taking, a value he brought to the classroom:

To solve any problem, you first must be able to understand the individual you have the problem with—because once you understand how they think and feel, finding the solution becomes easy. It is important for students to be globally competent so they too can also understand how people feel and think.

The reason global competence is important for students to learn, said a science teacher, is so that they can “understand their own and other perspectives, how to engage in RESPECTFUL dialogue, and finally how to take respectful action” (capitalization original). This teacher went on to say how empathy had become a personal mantra and a value he hopes to instill in his students. Another teacher commented, “Understanding how to listen and respond to a variety of perspectives is essential. Without those skills, we will not be able to work together to solve the problems plaguing our society.” Empathy and perspective-taking were considered important skills for communication and problem solving, not only in the context of future jobs, but also for current relationships and solving global social issues.

5.4.4. Transactional experiences

Transactional experiences involve experiential learning through dialogue and collaboration with people from different cultures and nations. This factor was the least coded in participants’ lesson plans and least reported by participants on the TGRS. Two categorical codes related to the theme are barriers to transactional experiences and bringing the world to the classroom.

5.4.4.1. Barriers to transactional experiences

Lack of international and technological resources were barriers to implementation of transactional experiences. In addition, some participants found the name of the factor difficult to remember. For example, an interview participant said, “ Transactional means working with other countries, right? For sure I’m weakest on that one.” She believed her students would benefit from and enjoy working with students from a different country, but she did not personally have international contacts.

Two participants wrote their global learning lesson plans on Native Americans. One teacher chose Native American culture because she had a personal relationship that served as a resource for the transactional experience factor of her lesson. The other teacher thought Native American issues would be both new and relevant to his students. While Native American nations are indeed sovereign, they are at the same time part of the U.S. Should teacher educators encourage their students to push beyond U.S. borders?

For two different participants, the technology component made transactional experiences difficult to include in their classrooms. One said, “I struggle with technology as well but am hoping to compile a database of resources for students to use during activities. My goal is to make a connection through one of the websites that I found and hope we can have a meaningful connection with another teacher, individual or student from around the world.” The other teacher stated her issue was student access to technology: “I am still not in a place to fully carry out a SUCCESSFUL global lesson plan. My first issue is resources. The lessons I have reviewed require a lot of technology. I can barely access technology for my students to write a paper.” Although lack of resources acted as barriers to transactional experiences, participants became creative as they imagined what could be implemented in their classrooms.

5.4.4.2. Bringing the world to the classroom

Connecting with students in other countries is just one way to incorporate transactional experiences. An English teacher considered bringing in experts from diverse countries to interact with her students, saying:

I hope that by bringing an expert to the classroom to discuss topics, my students will work on their speaking and listening skills, and will gain global perspectives that they have not been exposed to in the past. I plan to bring physical people into the classroom, as well as using online resources to do live interviews.

Another English teacher had a similar idea; however, she stated some concerns:

I need to get better at incorporating expert voices for my students’ projects. I get nervous about the last minute timing of multiple events at my school. On the other side, asynchronous technology would take care of this worry and allow the expert to respond to each question on their own time.

This teacher, and others, were not sure how to find experts from multiple perspectives. Another participant stated, “Without networks of people to call upon in each sub-topic, it was difficult to identify opportunities in which students could speak to a person from another culture or region of the world.” A charter school teacher shared that his school had lists of expert speakers (called Nespris) and a teacher from a culturally diverse school described how she had observed a teacher leveraging cultural and content expertise through her students’ networks. How to best utilize these experts was then negotiated by participants in discussion posts. Participants felt that experts could help students understand their content on a global scale and also give students practice engaging with people from different cultures in ways that “are respectful and celebratory of cultural differences.”

Overall, participants found transactional experiences with international partners the most challenging aspect to implement in their classrooms, and admittedly, we were also unable to include a coveted discussion with international partners during the graduate course. However, participants believed such interactions would be valuable in learning about different perspectives and practicing civil discourse.

6. Discussion

This mixed methods study examined self-report data of teachers’ globally competent teaching practices and perceptions. Quantitative data showed how and with what frequency participants infused global learning into their classrooms; qualitative findings reveal successes and challenges faced by participants when implementing globally competent teaching practices. This study contributes to the research literature the voices of teachers—voices needed for deeper conceptual understanding of translating global education theory to practice ( Kerkhoff, 2017 ).

6.1. Implications for research and practice

Quantitative analyses compared teachers from a business-as-usual graduate teaching course (controls) and teachers whose graduate course specifically infused global competence with its curriculum (focal group). Results revealed that, compared to controls, focal teachers practiced more globally competent teaching strategies in their K-12 classrooms at least once in the recent past (two weeks). Specifically, the following globally competent strategies were used with statistically greater frequency by focal teachers: guiding students to examine their own cultural identities, using texts written by global authors, and asking students to use primary sources when building claims. Across a semester, focal teachers reported building a repertoire of global-education resources with statistically greater frequency than did their control counterparts.

Based on our findings, we propose that exposure to globally competent teaching in teacher education relates to participants’ frequency of global teaching practices in K-12 classrooms. However, because we did not use pre and post paired t -tests, we are unable to infer that the relationship is causal. To ascertain if differences in globally competent teaching practices are caused by course integration of global learning, future studies should use TGRS to collect, pair, and analyze pre- and post- data in students from a globally-competent graduate teaching course and control group.

As a reflection tool for global teaching, TGRS may provide teachers with practical ideas to implement in their classrooms. According to our qualitative data, teachers found GTM a useful framework for translating theory into practice, reporting their ability to implement strategies immediately in their K-12 classrooms. In summary, qualitative data showed how participants implemented global learning by internationalizing existing culturally relevant pedagogical practices or by instituting desired pedagogies that opened a space for introducing global curriculum. Participants internationalized their curricula by infusing cultural understandings of content, teaching perspective-taking, and resisting Western-centric texts. Participants found entry points into global learning through their students’ cultural identities and international current events.

Quantitative data showed the following strategies were implemented in participants’ teaching at the end of the master’s course and with greater frequency than the controls: (a) using texts written by authors from diverse countries including primary sources, (b) reflecting on one's own assumptions and biases, (c) guiding students to examine their cultural identities, (d) discussing international current events, and (e) building a repertoire of resources related to global education. Analysis across quantitative and qualitative data suggests that providing information and examples on situated, integrated, and critical practices holds potential for influencing teachers’ globally competent teaching, but that teachers need more support in order to begin practices related to the transactional factor.

Qualitative results corroborate three well-documented barriers to implementing globally competent education: (a) lack of global resources, (b) mandated curriculum lacking in global competence, and (c) teaching tied to high-stakes tests that do not assess global competence ( Ferguson-Patrick et al., 2018 ; Kopish et al., 2019 ; Rapoport, 2010 ). In addition to the pressures to bring students to grade-level, cover a mandated and crowded curriculum, and ensure students pass high-stakes tests, our participants also felt a tension between the preparation they received from a culturally relevant lens that focused on the local and their perception that globally competent teaching focused solely on the global. The course provided a space to study culturally relevant pedagogy and global teaching side-by-side. Through course readings and discussions, participants were able to negotiate the local-global tension and conclude that many of their local communities were globally interconnected and that the model connected the local with the global rather than separating the two into a false dichotomy. Recognizing opposition to global education as problematic, most participants expressed desire to implement global competence into their teaching practices but needed to learn pedagogical moves that they can employ in K-12 classrooms.

Data from this study reveal the importance of educating teachers on how to enact global competence in K-12 classrooms, corroborating Reimer and McLean finding that teachers need a nuanced understanding of global education situated within classroom contexts ( 2009 ) and providing support for the application of the GTM as a framework for implementing global teaching practices. After extensive review of the literature, Yemini et al. (2019) concluded that there is a “need for comprehensive, dynamic frameworks for [global education in] teacher education to encompass… emerging trends in the literature ([e.g.] …the use of ICTs [information and communication technologies] and political changes)” (p. 88). The GTM includes both ICTs (in the transactional factor) and political relationships (in the critical factor), filling the need assessed by Yemini and colleagues.

6.2. Continued validation of the global teaching model

Validation of psychometric instruments and empirical models is a continuous process. Because of their theoretical importance, we added back to TGRS three items that did not load on the previous factor analysis. This study contributes both quantitative and qualitative support for keeping these three items ( texts by authors from diverse countries, guided students to examine their cultural identity, and reflect on my own assumptions and biases ). The results of this study indicate the four subscales, and the scale as a whole, are reliable according to a test of Cronbach’s alpha ( α = .89).

In the quantitative analysis, participants’ lowest-scoring factor was transactional experiences. This dimension requires experiential learning with different cultures, both face-to-face and through the use of ICTs. In the qualitative analysis, this factor also did not appear frequently. A few participants found it difficult to implement interactions with diverse others and even had trouble remembering the factor’s name. While the word “transaction” was originally chosen to signify the trans formative experiences and socio-political action that are integral components of global learning, this meaning was not effectively transferred through the word “transactional.” In fact, this term has a negative connotation in some education leadership circles (see Bass, 1998 ).

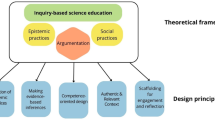

By synthesizing the research literature, the theoretical framework, the Global Teaching Model ( Kerkhoff, 2017 ), and the results of this study, we renamed the fourth dimension and created Fig. 2 as a heuristic for global teaching that works to decolonize curricula and raise sociocultural consciousness.

The Global Teaching Model with four factors: situated, integrated, critical, and intercultural.

The fourth dimension is renamed intercultural collaboration for transformative action. Intercultural means an exchange between two cultures. Transformative implies that the action does not reinforce hegemony. During intercultural collaboration, students engage in egalitarian transactions of different perspectives in order to learn with diverse others ( Wahlström, 2014 ). Teachers, students, and partners work together to critically analyze global issues exposing how inequities occur and then advocate for equity. Students take action towards social justice in both their local and global communities and in solidarity with people who have historically been marginalized by globalization ( Apple, 2011 ; Choo, 2017 ; OöConnor & Zeichner, 2011 ).

Freire (1970) considered praxis, or action based on theory, to be an essential component of critical pedagogy. As O’Connor and Zeichner state, “Merely heightening students’ awareness of global problems without cultivating in them a sense of efficacy to take part in transformative action might in fact make students less likely to become empathetic citizens” ( 2011, p. 532 ). Empowering students to take action on global and sociocultural issues provides space for hope in the curriculum. Without transformative action, students may feel powerless against systematic oppression around the world. Because our data show that intercultural collaboration was difficult for teachers to implement, one implication of our study is that teacher education programs could leverage their university’s international partnerships to introduce teachers to potential partners.

7. Conclusion

Gorski (2008) and Hauerwas and Creamer (2018) warn that, even when global partners or issues are introduced in the classroom, more often than not, schools reinforce rather than dismantle existing hierarchies. Teacher education must not only explain the theoretical reasons why global education is important, but must also model how to implement decolonizing practices and consciousness-raising in ways that teachers can replicate in K-12 settings. Without decolonizing and consciousness-raising, global education may emulate colonial power structures of domination and oppression. It is therefore essential to bring critical theory to the forefront of globally competent teacher education.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Longview Foundation, US.

Appendix C Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101629 .

Appendix A.

Going Global Module 6 Instructional Plan

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KwL3hsNLcVQ9xPEiWvpODyaxcptLsIz-/view?usp=sharing

Appendix B.

Interview protocol.

- 1) What kinds of knowledge and skills are important for being a globally competent person?

- 2) How did the global learning experiences in our course impact you personally?

- 3) Communicating ideas effectively with diverse audiences was an important learning outcome for the course. What aspects of the course contributed to your working towards this objective?

- 4) In what way has our course helped awaken, expand or strengthen your vision for education for all students? What new ideas do you have for promoting global communication and learning?

- 5) What recommendations do you have to enrich, improve or continue this global learning among future students who are taking education courses?

- 6) Do you think your pre- and post self-assessment on Teaching for Global Readiness was accurate? Explain why or why not.

- 7) Select at least two items in which you feel you made the most progress during this semester. What course experiences and class materials contributed to these changes and learning and why?

- 8) Select at least two items in which you feel like you didn’t make gains or that perhaps you need more work on. For each item reflect on: Why you feel you didn’t show growth in this area?

And any needed follow-up questions for clarification or further information.

Appendix C. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

- Andreotti V. Postcolonial and post-critical ‘global citizenship education. In: Elliot G., Fourali C., Issler S., editors. Education and social change: Connecting local and global perspectives. Continuum; New York: 2010. pp. 238–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- Apple M.W. Global crises, social justice, and teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education. 2011; 62 (2):222–234. [ Google Scholar ]

- Asia Society . 2018. Mapping the nation. https://asiasociety.org/mapping-nation/missouri Retrieved on 2 July 2019 from. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bass B. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1998. Transformational leadership: Industrial, military and educational impact. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carano K.T. Global educators’ personal attribution of a global perspective. Journal of International Social Studies. 2013; 3 (1):4–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Choo S. Global education and its tensions: case studies of two schools in Singapore and the United States. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. 2017; 27 (4):552–566. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell J.W., Plano Clark V.L., Gutmann M.L., Hanson W.E. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashhakkari A., Teddle C., editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. pp. 209–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- Delpit L. New Press; New York: 2006. Other people's children: Cultural conflict in the classroom [eBook] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferguson-Patrick K., Reynolds R., Macqueen S. Integrating curriculum: A case study of teaching Global Education. European Journal of Teacher Education. 2018; 41 (2):187–201. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freire P. Continuum.; New York: 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fujikane H. Approaches to global education in the United States, United Kingdom and Japan. International Review of Education. 2003; 49 :133–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gorski P.C. Good intentions are not enough: A decolonizing intercultural education. Intercultural Education. 2008; 19 (6):515–525. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamilton M.L., Pinnegar S. On the threshold of a new century: Trustworthiness, integrity, and self-study in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education. 2000; 51 (3):234–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hauerwas L.B., Creamer M. Engaging with host schools to establish the reciprocity of an international teacher education partnership. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement. 2018; 22 (2):157–188. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hull G.A., Stornaiuolo A. Cosmopolitan literacies, social networks, and “proper distance”: Striving to understand in a global world. Curriculum Inquiry. 2014; 44 (1):15–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hulsey P. KMOV4; 2016. Leads nation in growing immigrant population. https://www.kmov.com/news/st-louis-leads-nation-in-growing-immigrant-population/article_7c67687f-e994-5eb5-a646-747b80cd35e4.html Sept 22 Retrieved on 2 July 2019 from. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kerkhoff S. Addressing diversity in literacy instruction. Emerald; 2018. Teaching for global readiness: A model for locally situated and globally connected literacy instruction. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kerkhoff S.N. Designing global futures: A mixed methods study to develop and validate the teaching for global readiness scale. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2017; 65 :91–106. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kerkhoff S.N., Dimitrieska V., Woerner J., Alsup J. Global teaching in Indiana: A quantitative case study of K-12 public school teachers. Journal of Comparative Studies and International Education (JCSIE) 2019; 1 (1):5–31. [ Google Scholar ]