Psychology Unlocked

The free online psychology textbook, social psychology research topics.

January 24, 2017 Daniel Edward Blog , Social Psychology 0

Whether you’re looking for social psychology research topics for your A-Level or AP Psychology class, or considering a research question to explore for your Psychology PhD, the Psychology Unlocked list of social psychology research topics provides you with a strong list of possible avenues to explore.

Where possible we include links to university departments seeking PhD applications for certain projects. Even if you are not yet considering PhD options, these links may prove useful to you in developing your undergraduate or masters dissertation.

Lots of university psychology departments provide contact details on their websites.

If you read a psychologist’s paper and have questions that you would like to learn more about, drop them an email.

Lots of psychologists are very happy to receive emails from genuinely interested students and are often generous with their time and expertise… and those who aren’t will just overlook the email, so no harm done either way!

Psychology eZine

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for videos, articles, news and more.

We use Sendinblue as our marketing platform. By Clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provided will be transferred to Sendinblue for processing in accordance with their terms of use

- The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Why we think we know more than we do

- The Yale Food Addiction Scale: Are you addicted to food?

- Addicted to Pepsi Max? Understand addiction in six minutes (video)

- Functional Fixedness: The cognitive bias and how to beat it

- Summer Spending Spree! How Summer Burns A Hole In Your Pocket

What social factors are involved with the development of aggressive thoughts and behaviours? Is aggression socially-defined? Do different societies have differing definitions of aggression?

There has recently been a significant amount of research conducted on the influence of video games and television on aggression and violent behaviour.

Some research has been based on high-profile case studies, such as the aggressive murder of Jamie Bulger in 1993 by two children (Robert Thompson and Jon Venables). There is also a significant body of experimental research.

Attachment and Relationships

This is a huge area of research with lots of crossover into developmental psychology. What draws people together? How do people connect emotionally? What is love? What is friendship? What happens if someone doesn’t form an attachment with a parental figure?

This area includes research on attachment styles (at various stages of life), theories of love, friendship and attraction.

Attitudes and Attitude Change

Attitudes are a relatively enduring and general evaluation of something. Individuals hold attitudes on everything in life, from other people to inanimate objects, groups to ideologies.

Attitudes are thought to involve three components: (1) affective (to do with emotions), (2) behavioural, and (3) cognitive (to do with thoughts).

Research on attitudes can be closely linked to Prejudice (see below).

Authority and Leadership

Perhaps the most famous study of authority is Milgram’s (1961) Obedience to Authority . This research area has grown into a far-reaching and influential topic.

Research considers both positive and negative elements of authority, and applied psychology studies consider the role of authority in a particular social setting, such as advertising, in the workplace, or in a classroom.

The Psychology of Crowds (Le Bon, 1895) paved a path for a fascinating area of social psychology that considers the social group as an active player.

Groups tend to act differently from individuals, and specific individuals will act differently depending on the group they are in.

Social psychology research topics about groups consider group dynamics, leadership (see above), group-think and decision-making, intra-group and inter-group conflict, identities (see below) and prejudices (see below).

Gordon Allport’s (1979) ‘The Nature of Prejudice’ is a seminal piece on group stereotyping and discrimination.

Social psychologists consider what leads to the formation of stereotypes and prejudices. How and why are prejudices used? Why do we maintain inaccurate stereotypes? What are the benefits and costs of prejudice?

This interesting blog post on the BPS Digest Blog may provide some inspiration for research into prejudice and political uncertainty.

Pro- and Anti-Social Behaviour

Behaviours are only pro- or anti-social because of social norms that suggest so. Social Psychologists therefore investigate the roots of these behaviours as well as considering what happens when social norms are ignored.

Within this area of social psychology, researchers may consider why people help others (strangers as well as well as known others). Another interesting question regards the factors that might deter an individual from acting pro-socially, even if they are aware that a behaviour is ‘the right thing to do’.

The bystander effect is one such example of social inaction.

Self and Social Identity

Tajfel and Turner (1979) proposed Social Identity Theory and a large body of research has developed out of the concepts of self and social identity (or identities).

Questions in this area include: what is identity? What is the self? Does a social identity remain the same across time and space? What are the contributory factors to an individual’s social identity?

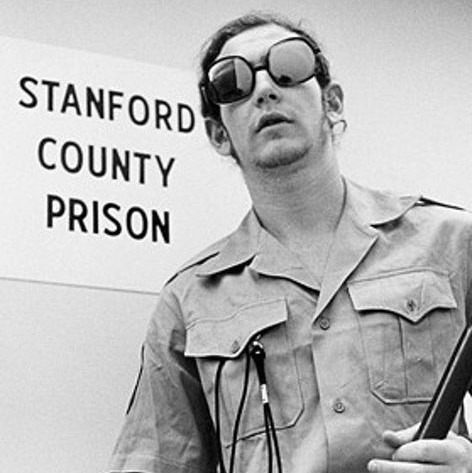

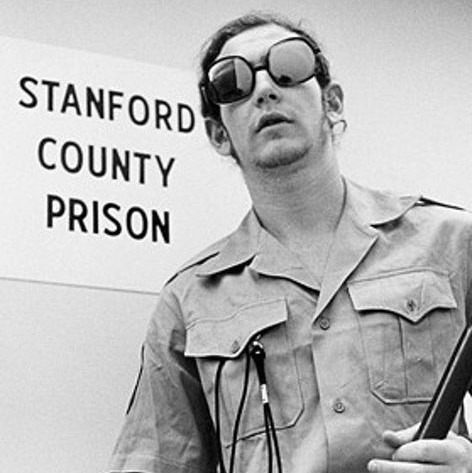

Zimbardo’s (1972) Stanford Prison Experiment famously considered the role of social identities.

Research in this area also links with work on groups (see above), social cognition (see below), and prejudices (see above).

Social Cognition

Social cognition regards the way we think and use information. It is the cross-over point between the fields of social and cognitive psychology.

Perhaps the most famous concept in this area is that of schemas – general ideas about the world, which allow us to make sense of new (and old) information quickly.

Social cognition also includes those considering heuristics (mental shortcuts) and some cognitive biases.

Social Influence

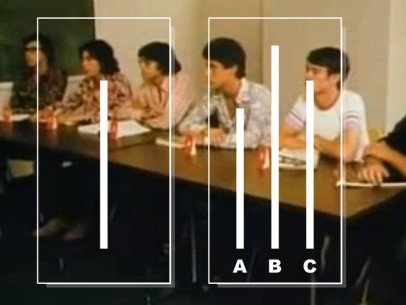

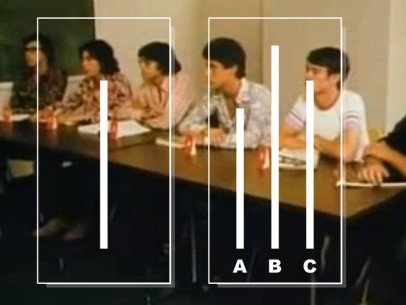

This is one of the first areas of social psychology that most students learn. Remember the social conformity work by Asch (1951) on the length of lines?

Other social psychology research topics within this area include persuasion and peer-pressure.

Social Representations

Social Representations (Moscovici, 1961) ‘make something unfamiliar, or unfamiliarity itself, familiar’ (Moscovici, 1984). This is a theory with its academic roots in Durkheim’s theory of collective representations.

Researchers working within this framework consider the social role of knowledge. How does information translate from the scientific realm of expert knowledge to the socially accessible realm of the layperson? How do we make sense of new information? How do we organise separate and distinct facts in a way that make sense to our needs?

One of the most famous studies using Social Representations Theory is Jodelet’s (1991) study of madness.

- Social Article

- Social Psychology

Copyright © 2024 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1. Introducing Social Psychology

1.3 Conducting Research in Social Psychology

Learning Objectives

- Explain why social psychologists rely on empirical methods to study social behavior.

- Provide examples of how social psychologists measure the variables they are interested in.

- Review the three types of research designs, and evaluate the strengths and limitations of each type.

- Consider the role of validity in research, and describe how research programs should be evaluated.

Social psychologists are not the only people interested in understanding and predicting social behavior or the only people who study it. Social behavior is also considered by religious leaders, philosophers, politicians, novelists, and others, and it is a common topic on TV shows. But the social psychological approach to understanding social behavior goes beyond the mere observation of human actions. Social psychologists believe that a true understanding of the causes of social behavior can only be obtained through a systematic scientific approach, and that is why they conduct scientific research. Social psychologists believe that the study of social behavior should be empirical —that is, based on the collection and systematic analysis of observable data .

The Importance of Scientific Research

Because social psychology concerns the relationships among people, and because we can frequently find answers to questions about human behavior by using our own common sense or intuition, many people think that it is not necessary to study it empirically (Lilienfeld, 2011). But although we do learn about people by observing others and therefore social psychology is in fact partly common sense, social psychology is not entirely common sense.

Is social psychology just common sense?

To test for yourself whether or not social psychology is just common sense, try doing this activity. Based on your past observations of people’s behavior, along with your own common sense, you will likely have answers to each of the questions on the activity. But how sure are you? Would you be willing to bet that all, or even most, of your answers have been shown to be correct by scientific research? If you are like most people, you will get at least some of these answers wrong.

Read through each finding, and decide if you think the research evidence shows that it is either mainly true or mainly false. When you have figured out the answers, think about why each finding is either mainly true or mainly false. You may also find some other ideas on this as you work your way through the textbook chapters!

- Opposites attract.

- An athlete who wins the bronze medal (third place) in an event is happier about his or her performance than the athlete who won the silver medal (second place).

- Having good friends you can count on can keep you from catching colds.

- Subliminal advertising (i.e., persuasive messages that are presented out of our awareness on TV or movie screens) is very effective in getting us to buy products.

- The greater the reward promised for an activity, the more one will come to enjoy engaging in that activity.

- Physically attractive people are seen as less intelligent than less attractive people.

- Punching a pillow or screaming out loud is a good way to reduce frustration and aggressive tendencies.

- People pull harder in a tug-of-war when they’re pulling alone than when pulling in a group.

H5P: TEST YOUR LEARNING: CHAPTER 1 DRAG THE WORDS – CLASSIC FINDINGS IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

Read through each finding, taken from Table 1.5 in the chapter summary, and decide if you think the research evidence shows that it is either mainly true or mainly false by dragging the correct word into each box. Pay attention to the number of “trues” and “falses” available! When you have figured out the answers, think about why each finding is either mainly true or mainly false. You may also find some other ideas on this as you work your way through the textbook chapters!

- An athlete who wins the bronze medal (third place) in an event is happier about his or her performance than the athlete who wins the silver medal (second place).

- Subliminal advertising (i.e., persuasive messages that are displayed out of our awareness on TV or movie screens) is very effective in getting us to buy products.

See Table 1.5 in the chapter summary for answers and explanations.

One of the reasons we might think that social psychology is common sense is that once we learn about the outcome of a given event (e.g., when we read about the results of a research project), we frequently believe that we would have been able to predict the outcome ahead of time. For instance, if half of a class of students is told that research concerning attraction between people has demonstrated that “opposites attract,” and if the other half is told that research has demonstrated that “birds of a feather flock together,” most of the students in both groups will report believing that the outcome is true and that they would have predicted the outcome before they had heard about it. Of course, both of these contradictory outcomes cannot be true. The problem is that just reading a description of research findings leads us to think of the many cases that we know that support the findings and thus makes them seem believable. The tendency to think that we could have predicted something that we probably would not have been able to predict is called the hindsight bias .

Our common sense also leads us to believe that we know why we engage in the behaviors that we engage in, when in fact we may not. Social psychologist Daniel Wegner and his colleagues have conducted a variety of studies showing that we do not always understand the causes of our own actions. When we think about a behavior before we engage in it, we believe that the thinking guided our behavior, even when it did not (Morewedge, Gray, & Wegner, 2010). People also report that they contribute more to solving a problem when they are led to believe that they have been working harder on it, even though the effort did not increase their contribution to the outcome (Preston & Wegner, 2007). These findings, and many others like them, demonstrate that our beliefs about the causes of social events, and even of our own actions, do not always match the true causes of those events.

Social psychologists conduct research because it often uncovers results that could not have been predicted ahead of time. Putting our hunches to the test exposes our ideas to scrutiny. The scientific approach brings a lot of surprises, but it also helps us test our explanations about behavior in a rigorous manner. It is important for you to understand the research methods used in psychology so that you can evaluate the validity of the research that you read about here, in other courses, and in your everyday life.

Social psychologists publish their research in scientific journals, and your instructor may require you to read some of these research articles. The most important social psychology journals are listed in “ Social Psychology Journals .” If you are asked to do a literature search on research in social psychology, you should look for articles from these journals.

Social Psychology Journals:

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

- Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

- Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

- Social Psychology and Personality Science

- Social Cognition

- European Journal of Social Psychology

- Social Psychology Quarterly

- Basic and Applied Social Psychology

- Journal of Applied Social Psychology

Note. The research articles in these journals are likely to be available in your college or university library.

We’ll discuss the empirical approach and review the findings of many research projects throughout this book, but for now let’s take a look at the basics of how scientists use research to draw overall conclusions about social behavior. Keep in mind as you read this book, however, that although social psychologists are pretty good at understanding the causes of behavior, our predictions are a long way from perfect. We are not able to control the minds or the behaviors of others or to predict exactly what they will do in any given situation. Human behavior is complicated because people are complicated and because the social situations that they find themselves in every day are also complex. It is this complexity—at least for me—that makes studying people so interesting and fun.

Measuring Affect, Behavior, and Cognition

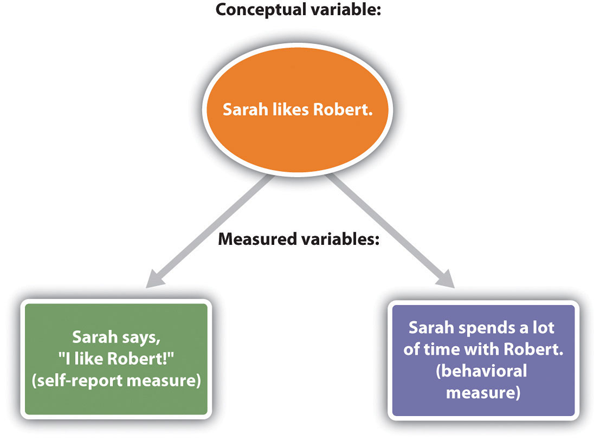

One important aspect of using an empirical approach to understand social behavior is that the concepts of interest must be measured (Figure 1.7, “The Operational Definition”). If we are interested in learning how much Sarah likes Robert, then we need to have a measure of her liking for him. But how, exactly, should we measure the broad idea of “liking”? In scientific terms, the characteristics that we are trying to measure are known as conceptual variables , and the particular method that we use to measure a variable of interest is called an operational definition.

For anything that we might wish to measure, there are many different operational definitions, and which one we use depends on the goal of the research and the type of situation we are studying. To better understand this, let’s look at an example of how we might operationally define “Sarah likes Robert.”

One approach to measurement involves directly asking people about their perceptions using self-report measures. Self-report measures are measures in which individuals are asked to respond to questions posed by an interviewer or on a questionnaire . Generally, because any one question might be misunderstood or answered incorrectly, in order to provide a better measure, more than one question is asked and the responses to the questions are averaged together. For example, an operational definition of Sarah’s liking for Robert might involve asking her to complete the following measure:

- I enjoy being around Robert. Strongly disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Strongly agree

- I get along well with Robert. Strongly disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Strongly agree

- I like Robert. Strongly disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Strongly agree

The operational definition would be the average of her responses across the three questions. Because each question assesses the attitude differently, and yet each question should nevertheless measure Sarah’s attitude toward Robert in some way, the average of the three questions will generally be a better measure than would any one question on its own.

Although it is easy to ask many questions on self-report measures, these measures have a potential disadvantage. As we have seen, people’s insights into their own opinions and their own behaviors may not be perfect, and they might also not want to tell the truth—perhaps Sarah really likes Robert, but she is unwilling or unable to tell us so. Therefore, an alternative to self-report that can sometimes provide a more valid measure is to measure behavior itself. Behavioral measures are measures designed to directly assess what people do . Instead of asking Sarah how much she likes Robert, we might instead measure her liking by assessing how much time she spends with Robert or by coding how much she smiles at him when she talks to him. Some examples of behavioral measures that have been used in social psychological research are shown in Table 1.3, “Examples of Operational Definitions of Conceptual Variables That Have Been Used in Social Psychological Research.”

Social Neuroscience: Measuring Social Responses in the Brain

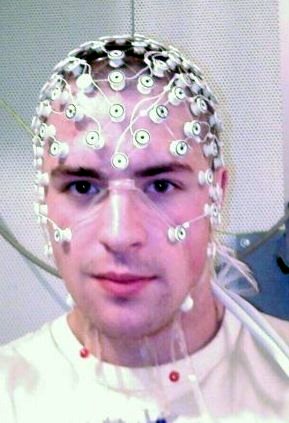

Still another approach to measuring thoughts and feelings is to measure brain activity, and recent advances in brain science have created a wide variety of new techniques for doing so. One approach, known as electroencephalography (EEG) , is a technique that records the electrical activity produced by the brain’s neurons through the use of electrodes that are placed around the research participant’s head . An electroencephalogram (EEG) can show if a person is asleep, awake, or anesthetized because the brain wave patterns are known to differ during each state. An EEG can also track the waves that are produced when a person is reading, writing, and speaking with others. A particular advantage of the technique is that the participant can move around while the recordings are being taken, which is useful when measuring brain activity in children who often have difficulty keeping still. Furthermore, by following electrical impulses across the surface of the brain, researchers can observe changes over very fast time periods.

Although EEGs can provide information about the general patterns of electrical activity within the brain, and although they allow the researcher to see these changes quickly as they occur in real time, the electrodes must be placed on the surface of the skull, and each electrode measures brain waves from large areas of the brain. As a result, EEGs do not provide a very clear picture of the structure of the brain.

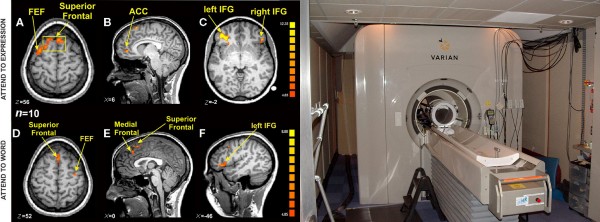

But techniques exist to provide more specific brain images. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a neuroimaging technique that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain structure and function . In research studies that use the fMRI, the research participant lies on a bed within a large cylindrical structure containing a very strong magnet. Nerve cells in the brain that are active use more oxygen, and the need for oxygen increases blood flow to the area. The fMRI detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region and thus is an indicator of which parts of the brain are active.

Very clear and detailed pictures of brain structures (see Figure 1.9, “MRI BOLD activation in an emotional Stroop task”) can be produced via fMRI. Often, the images take the form of cross-sectional “slices” that are obtained as the magnetic field is passed across the brain. The images of these slices are taken repeatedly and are superimposed on images of the brain structure itself to show how activity changes in different brain structures over time. Normally, the research participant is asked to engage in tasks while in the scanner, for instance, to make judgments about pictures of people, to solve problems, or to make decisions about appropriate behaviors. The fMRI images show which parts of the brain are associated with which types of tasks. Another advantage of the fMRI is that is it noninvasive. The research participant simply enters the machine and the scans begin.

Although the scanners themselves are expensive, the advantages of fMRIs are substantial, and scanners are now available in many university and hospital settings. The fMRI is now the most commonly used method of learning about brain structure, and it has been employed by social psychologists to study social cognition, attitudes, morality, emotions, responses to being rejected by others, and racial prejudice, to name just a few topics (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Lieberman, Hariri, Jarcho, Eisenberger, & Bookheimer, 2005; Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002; Richeson et al., 2003).

Observational Research

Once we have decided how to measure our variables, we can begin the process of research itself. As you can see in Table 1.4, “Three Major Research Designs Used by Social Psychologists,” there are three major approaches to conducting research that are used by social psychologists—the observational approach , the correlational approach , and the experimental approach . Each approach has some advantages and disadvantages.

The most basic research design, observational research , is research that involves making observations of behavior and recording those observations in an objective manner . Although it is possible in some cases to use observational data to draw conclusions about the relationships between variables (e.g., by comparing the behaviors of older versus younger children on a playground), in many cases the observational approach is used only to get a picture of what is happening to a given set of people at a given time and how they are responding to the social situation. In these cases, the observational approach involves creating a type of “snapshot” of the current state of affairs.

One advantage of observational research is that in many cases it is the only possible approach to collecting data about the topic of interest. A researcher who is interested in studying the impact of an earthquake on the residents of Tokyo, the reactions of Israelis to a terrorist attack, or the activities of the members of a religious cult cannot create such situations in a laboratory but must be ready to make observations in a systematic way when such events occur on their own. Thus observational research allows the study of unique situations that could not be created by the researcher. Another advantage of observational research is that the people whose behavior is being measured are doing the things they do every day, and in some cases they may not even know that their behavior is being recorded.

One early observational study that made an important contribution to understanding human behavior was reported in a book by Leon Festinger and his colleagues (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956). The book, called When Prophecy Fails , reported an observational study of the members of a “doomsday” cult. The cult members believed that they had received information, supposedly sent through “automatic writing” from a planet called “Clarion,” that the world was going to end. More specifically, the group members were convinced that Earth would be destroyed as the result of a gigantic flood sometime before dawn on December 21, 1954.

When Festinger learned about the cult, he thought that it would be an interesting way to study how individuals in groups communicate with each other to reinforce their extreme beliefs. He and his colleagues observed the members of the cult over a period of several months, beginning in July of the year in which the flood was expected. The researchers collected a variety of behavioral and self-report measures by observing the cult, recording the conversations among the group members, and conducting detailed interviews with them. Festinger and his colleagues also recorded the reactions of the cult members, beginning on December 21, when the world did not end as they had predicted. This observational research provided a wealth of information about the indoctrination patterns of cult members and their reactions to disconfirmed predictions. This research also helped Festinger develop his important theory of cognitive dissonance.

Despite their advantages, observational research designs also have some limitations. Most importantly, because the data that are collected in observational studies are only a description of the events that are occurring, they do not tell us anything about the relationship between different variables. However, it is exactly this question that correlational research and experimental research are designed to answer.

The Research Hypothesis

Because social psychologists are generally interested in looking at relationships among variables, they begin by stating their predictions in the form of a precise statement known as a research hypothesis . A research hypothesis is a specific prediction about the relationship between the variables of interest and about the specific direction of that relationship . For instance, the research hypothesis “People who are more similar to each other will be more attracted to each other” predicts that there is a relationship between a variable called similarity and another variable called attraction. In the research hypothesis “The attitudes of cult members become more extreme when their beliefs are challenged,” the variables that are expected to be related are extremity of beliefs and the degree to which the cult’s beliefs are challenged.

Because the research hypothesis states both that there is a relationship between the variables and the direction of that relationship, it is said to be falsifiable, which means that the outcome of the research can demonstrate empirically either that there is support for the hypothesis (i.e., the relationship between the variables was correctly specified) or that there is actually no relationship between the variables or that the actual relationship is not in the direction that was predicted . Thus the research hypothesis that “People will be more attracted to others who are similar to them” is falsifiable because the research could show either that there was no relationship between similarity and attraction or that people we see as similar to us are seen as less attractive than those who are dissimilar.

Correlational Research

Correlational research is designed to search for and test hypotheses about the relationships between two or more variables. In the simplest case, the correlation is between only two variables, such as that between similarity and liking, or between gender (male versus female) and helping.

In a correlational design, the research hypothesis is that there is an association (i.e., a correlation) between the variables that are being measured. For instance, many researchers have tested the research hypothesis that a positive correlation exists between the use of violent video games and the incidence of aggressive behavior, such that people who play violent video games more frequently would also display more aggressive behavior.

A statistic known as the Pearson correlation coefficient (symbolized by the letter r ) is normally used to summarize the association, or correlation, between two variables . The Pearson correlation coefficient can range from −1 (indicating a very strong negative relationship between the variables) to +1 (indicating a very strong positive relationship between the variables). Recent research has found that there is a positive correlation between the use of violent video games and the incidence of aggressive behavior and that the size of the correlation is about r = .30 (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010).

One advantage of correlational research designs is that, like observational research (and in comparison with experimental research designs in which the researcher frequently creates relatively artificial situations in a laboratory setting), they are often used to study people doing the things that they do every day. Correlational research designs also have the advantage of allowing prediction. When two or more variables are correlated, we can use our knowledge of a person’s score on one of the variables to predict his or her likely score on another variable. Because high-school grades are correlated with university grades, if we know a person’s high-school grades, we can predict his or her likely university grades. Similarly, if we know how many violent video games a child plays, we can predict how aggressively he or she will behave. These predictions will not be perfect, but they will allow us to make a better guess than we would have been able to if we had not known the person’s score on the first variable ahead of time.

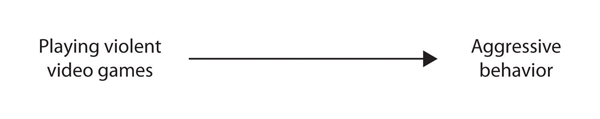

Despite their advantages, correlational designs have a very important limitation. This limitation is that they cannot be used to draw conclusions about the causal relationships among the variables that have been measured. An observed correlation between two variables does not necessarily indicate that either one of the variables caused the other. Although many studies have found a correlation between the number of violent video games that people play and the amount of aggressive behaviors they engage in, this does not mean that viewing the video games necessarily caused the aggression. Although one possibility is that playing violent games increases aggression,

another possibility is that the causal direction is exactly opposite to what has been hypothesized. Perhaps increased aggressiveness causes more interest in, and thus increased viewing of, violent games. Although this causal relationship might not seem as logical, there is no way to rule out the possibility of such reverse causation on the basis of the observed correlation.

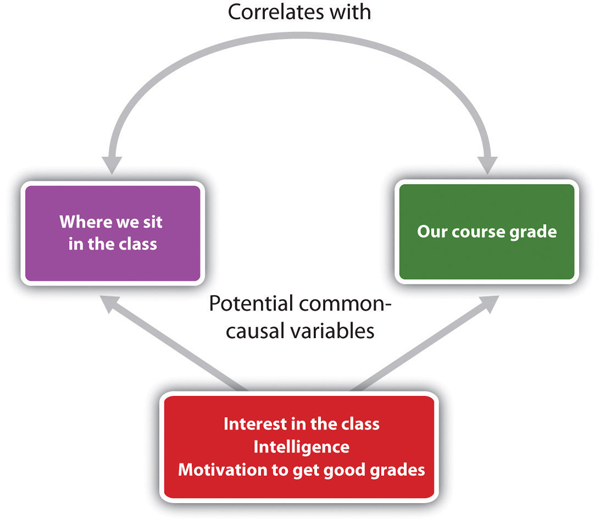

Still another possible explanation for the observed correlation is that it has been produced by the presence of another variable that was not measured in the research. Common-causal variables (also known as third variables ) are variables that are not part of the research hypothesis but that cause both the predictor and the outcome variable and thus produce the observed correlation between them (Figure 1.13, “Correlation and Causality”). It has been observed that students who sit in the front of a large class get better grades than those who sit in the back of the class. Although this could be because sitting in the front causes the student to take better notes or to understand the material better, the relationship could also be due to a common-causal variable, such as the interest or motivation of the students to do well in the class. Because a student’s interest in the class leads him or her to both get better grades and sit nearer to the teacher, seating position and class grade are correlated, even though neither one caused the other.

The possibility of common-causal variables must always be taken into account when considering correlational research designs. For instance, in a study that finds a correlation between playing violent video games and aggression, it is possible that a common-causal variable is producing the relationship. Some possibilities include the family background, diet, and hormone levels of the children. Any or all of these potential common-causal variables might be creating the observed correlation between playing violent video games and aggression. Higher levels of the male sex hormone testosterone, for instance, may cause children to both watch more violent TV and behave more aggressively.

You may think of common-causal variables in correlational research designs as “mystery” variables, since their presence and identity is usually unknown to the researcher because they have not been measured. Because it is not possible to measure every variable that could possibly cause both variables, it is always possible that there is an unknown common-causal variable. For this reason, we are left with the basic limitation of correlational research: correlation does not imply causation.

Experimental Research

The goal of much research in social psychology is to understand the causal relationships among variables, and for this we use experiments. Experimental research designs are research designs that include the manipulation of a given situation or experience for two or more groups of individuals who are initially created to be equivalent, followed by a measurement of the effect of that experience .

In an experimental research design, the variables of interest are called the independent variables and the dependent variables. The independent variable refers to the situation that is created by the experimenter through the experimental manipulations , and the dependent variable refers to the variable that is measured after the manipulations have occurred . In an experimental research design, the research hypothesis is that the manipulated independent variable (or variables) causes changes in the measured dependent variable (or variables). We can diagram the prediction like this, using an arrow that points in one direction to demonstrate the expected direction of causality:

viewing violence (independent variable) → aggressive behavior (dependent variable)

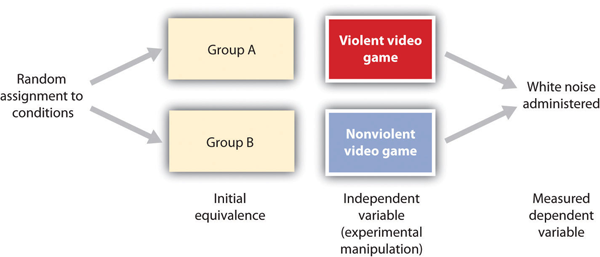

Consider an experiment conducted by Anderson and Dill (2000), which was designed to directly test the hypothesis that viewing violent video games would cause increased aggressive behavior. In this research, male and female undergraduates from Iowa State University were given a chance to play either a violent video game (Wolfenstein 3D) or a nonviolent video game (Myst). During the experimental session, the participants played the video game that they had been given for 15 minutes. Then, after the play, they participated in a competitive task with another student in which they had a chance to deliver blasts of white noise through the earphones of their opponent. The operational definition of the dependent variable (aggressive behavior) was the level and duration of noise delivered to the opponent. The design and the results of the experiment are shown in Figure 1.14, “An Experimental Research Design (After Anderson & Dill, 2000).”

Experimental designs have two very nice features. For one, they guarantee that the independent variable occurs prior to measuring the dependent variable. This eliminates the possibility of reverse causation. Second, the experimental manipulation allows ruling out the possibility of common-causal variables that cause both the independent variable and the dependent variable. In experimental designs, the influence of common-causal variables is controlled, and thus eliminated, by creating equivalence among the participants in each of the experimental conditions before the manipulation occurs.

The most common method of creating equivalence among the experimental conditions is through random assignment to conditions before the experiment begins, which involves determining separately for each participant which condition he or she will experience through a random process, such as drawing numbers out of an envelope or using a website such as randomizer.org . Anderson and Dill first randomly assigned about 100 participants to each of their two groups. Let’s call them Group A and Group B. Because they used random assignment to conditions, they could be confident that before the experimental manipulation occurred , the students in Group A were, on average , equivalent to the students in Group B on every possible variable , including variables that are likely to be related to aggression, such as family, peers, hormone levels, and diet—and, in fact, everything else.

Then, after they had created initial equivalence, Anderson and Dill created the experimental manipulation—they had the participants in Group A play the violent video game and the participants in Group B play the nonviolent video game. Then they compared the dependent variable (the white noise blasts) between the two groups and found that the students who had viewed the violent video game gave significantly longer noise blasts than did the students who had played the nonviolent game. When the researchers observed differences in the duration of white noise blasts between the two groups after the experimental manipulation, they could draw the conclusion that it was the independent variable (and not some other variable) that caused these differences because they had created initial equivalence between the groups. The idea is that the only thing that was different between the students in the two groups was which video game they had played.

When we create a situation in which the groups of participants are expected to be equivalent before the experiment begins, when we manipulate the independent variable before we measure the dependent variable, and when we change only the nature of independent variables between the conditions, then we can be confident that it is the independent variable that caused the differences in the dependent variable. Such experiments are said to have high internal validity, where internal validity is the extent to which changes in the dependent variable in an experiment can confidently be attributed to changes in the independent variable .

Despite the advantage of determining causation, experimental research designs do have limitations. One is that the experiments are usually conducted in laboratory situations rather than in the everyday lives of people. Therefore, we do not know whether results that we find in a laboratory setting will necessarily hold up in everyday life. To counter this, researchers sometimes conduct field experiments, which are experimental research studies that are conducted in a natural environment , such as a school or a factory . However, they are difficult to conduct because they require a means of creating random assignment to conditions, and this is frequently not possible in natural settings.

A second and perhaps more important limitation of experimental research designs is that some of the most interesting and important social variables cannot be experimentally manipulated. If we want to study the influence of the size of a mob on the destructiveness of its behavior, or to compare the personality characteristics of people who join suicide cults with those of people who do not join suicide cults, these relationships must be assessed using correlational designs because it is simply not possible to manipulate mob size or cult membership.

H5P: TEST YOUR LEARNING: CHAPTER 1 DRAG THE WORDS – INDEPENDENT AND DEPENDENT VARIABLES

Read through the following descriptions of experimental studies, and identify the independent and dependent variables in each scenario.

- Amount of aggression:

- Type of video game:

- Size of group of onlookers

- Speed of helping response

- Amount of attitude change

- Type of message

- Hostile intention bias score

- Type of word

- Target of attribution

- Type of attribution

Factorial Research Designs

Social psychological experiments are frequently designed to simultaneously study the effects of more than one independent variable on a dependent variable. Factorial research designs are experimental designs that have two or more independent variables . By using a factorial design, the scientist can study the influence of each variable on the dependent variable (known as the main effects of the variables) as well as how the variables work together to influence the dependent variable (known as the interaction between the variables). Factorial designs sometimes demonstrate the person by situation interaction.

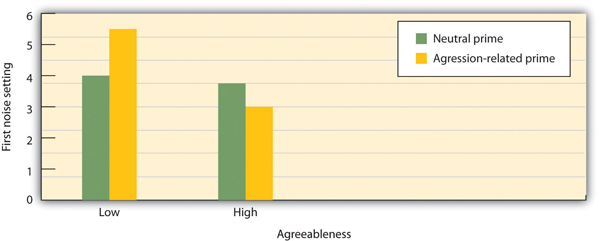

In one such study, Brian Meier and his colleagues (Meier, Robinson, & Wilkowski, 2006) tested the hypothesis that exposure to aggression-related words would increase aggressive responses toward others. Although they did not directly manipulate the social context, they used a technique common in social psychology in which they primed (i.e., activated) thoughts relating to social settings. In their research, half of their participants were randomly assigned to see words relating to aggression and the other half were assigned to view neutral words that did not relate to aggression. The participants in the study also completed a measure of individual differences in agreeableness —a personality variable that assesses the extent to which people see themselves as compassionate, cooperative, and high on other-concern.

Then the research participants completed a task in which they thought they were competing with another student. Participants were told that they should press the space bar on the computer keyboard as soon as they heard a tone over their headphones, and the person who pressed the space bar the fastest would be the winner of the trial. Before the first trial, participants set the intensity of a blast of white noise that would be delivered to the loser of the trial. The participants could choose an intensity ranging from 0 (no noise) to the most aggressive response (10, or 105 decibels). In essence, participants controlled a “weapon” that could be used to blast the opponent with aversive noise, and this setting became the dependent variable. At this point, the experiment ended.

As you can see in Figure 1.15, “A Person-Situation Interaction,” there was a person-by-situation interaction. Priming with aggression-related words (the situational variable) increased the noise levels selected by participants who were low on agreeableness, but priming did not increase aggression (in fact, it decreased it a bit) for students who were high on agreeableness. In this study, the social situation was important in creating aggression, but it had different effects for different people.

Deception in Social Psychology Experiments

You may have wondered whether the participants in the video game study that we just discussed were told about the research hypothesis ahead of time. In fact, these experiments both used a cover story — a false statement of what the research was really about . The students in the video game study were not told that the study was about the effects of violent video games on aggression, but rather that it was an investigation of how people learn and develop skills at motor tasks like video games and how these skills affect other tasks, such as competitive games. The participants in the task performance study were not told that the research was about task performance. In some experiments, the researcher also makes use of an experimental confederate — a person who is actually part of the experimental team but who pretends to be another participant in the study . The confederate helps create the right “feel” of the study, making the cover story seem more real.

In many cases, it is not possible in social psychology experiments to tell the research participants about the real hypotheses in the study, and so cover stories or other types of deception may be used. You can imagine, for instance, that if a researcher wanted to study racial prejudice, he or she could not simply tell the participants that this was the topic of the research because people may not want to admit that they are prejudiced, even if they really are. Although the participants are always told—through the process of informed consent —as much as is possible about the study before the study begins, they may nevertheless sometimes be deceived to some extent. At the end of every research project, however, participants should always receive a complete debriefing in which all relevant information is given, including the real hypothesis, the nature of any deception used, and how the data are going to be used.

H5P: TEST YOUR LEARNING: CHAPTER 1 DRAG THE WORDS – TYPES OF RESEARCH DESIGN

Now that you have reviewed the three main types of research design used in social psychology, read each brief summary of empirical findings below and identify which type of design the results were derived from – experimental, observational or correlational. Table 1.4 contains some helpful information here.

- There is a positive relationship between level of academic self-concept and self-esteem scores in university students.

- People are more persuaded if given a two-sided versus a one-sided message.

- People assigned to a group of four are more likely to conform to the dominant response in a perceptual task than people tasked with performing the task alone.

- People in individualistic cultures make predominantly internal attributions about the causes of social behavior.

- The more hours per month individuals spend doing voluntary work with people who are socially marginalized, the less they tend to believe in the just world hypothesis.

- 13 year-olds engage in more acts of relational aggression towards their peers than 8 year-olds.

Interpreting Research

No matter how carefully it is conducted or what type of design is used, all research has limitations. Any given research project is conducted in only one setting and assesses only one or a few dependent variables. And any one study uses only one set of research participants. Social psychology research is sometimes criticized because it frequently uses university students from Western cultures as participants (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). But relationships between variables are only really important if they can be expected to be found again when tested using other research designs, other operational definitions of the variables, other participants, and other experimenters, and in other times and settings.

External validity refers to the extent to which relationships can be expected to hold up when they are tested again in different ways and for different people . Science relies primarily upon replication—that is, the repeating of research —to study the external validity of research findings. Sometimes the original research is replicated exactly, but more often, replications involve using new operational definitions of the independent or dependent variables, or designs in which new conditions or variables are added to the original design. And to test whether a finding is limited to the particular participants used in a given research project, scientists may test the same hypotheses using people from different ages, backgrounds, or cultures. Replication allows scientists to test the external validity as well as the limitations of research findings.

In some cases, researchers may test their hypotheses, not by conducting their own study, but rather by looking at the results of many existing studies, using a meta-analysis — a statistical procedure in which the results of existing studies are combined to determine what conclusions can be drawn on the basis of all the studies considered together . For instance, in one meta-analysis, Anderson and Bushman (2001) found that across all the studies they could locate that included both children and adults, college students and people who were not in college, and people from a variety of different cultures, there was a clear positive correlation (about r = .30) between playing violent video games and acting aggressively. The summary information gained through a meta-analysis allows researchers to draw even clearer conclusions about the external validity of a research finding.

Figure 1.16 Some Important Aspects of the Scientific Approach

Scientists generate research hypotheses , which are tested using an observational, correlational, or experimental research design .

The variables of interest are measured using self-report or behavioral measures .

Data is interpreted according to its validity (including internal validity and external validity ).

The results of many studies may be combined and summarized using meta-analysis .

It is important to realize that the understanding of social behavior that we gain by conducting research is a slow, gradual, and cumulative process. The research findings of one scientist or one experiment do not stand alone—no one study proves a theory or a research hypothesis. Rather, research is designed to build on, add to, and expand the existing research that has been conducted by other scientists. That is why whenever a scientist decides to conduct research, he or she first reads journal articles and book chapters describing existing research in the domain and then designs his or her research on the basis of the prior findings. The result of this cumulative process is that over time, research findings are used to create a systematic set of knowledge about social psychology (Figure 1.16, “Some Important Aspects of the Scientific Approach”).

H5P: Test your Learning: Chapter 1 True or False Quiz

Try these true/false questions, to see how well you have retained some key ideas from this chapter!

- Social psychology is a scientific discipline.

- Cultural differences are rarely studied nowadays in social psychology because it has been established that all of its important concepts are universal.

- In social psychology, the primary focus in on the behavior of groups, not individuals.

- Factorial designs are a type of correlational research.

- Nonrandom assignments of participants to conditions in experimental social psychological research ensures that everyone has an equal chance of being in any of the conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Social psychologists study social behavior using an empirical approach. This allows them to discover results that could not have been reliably predicted ahead of time and that may violate our common sense and intuition.

- The variables that form the research hypothesis, known as conceptual variables, are assessed by using measured variables such as self-report, behavioral, or neuroimaging measures.

- Observational research is research that involves making observations of behavior and recording those observations in an objective manner. In some cases, it may be the only approach to studying behavior.

- Correlational and experimental research designs are based on developing falsifiable research hypotheses.

- Correlational research designs allow prediction but cannot be used to make statements about causality. Experimental research designs in which the independent variable is manipulated can be used to make statements about causality.

- Social psychological experiments are frequently factorial research designs in which the effects of more than one independent variable on a dependent variable are studied.

- All research has limitations, which is why scientists attempt to replicate their results using different measures, populations, and settings and to summarize those results using meta-analyses.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Using Google Scholar find journal articles that report observational, correlational, and experimental research designs. Specify the research design, the research hypothesis, and the conceptual and measured variables in each design.

- Liking another person

- Life satisfaction

- Visit the website Online Social Psychology Studies and take part in one of the online studies listed there.

Anderson, C. A., & Dill, K. E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (4), 772–790.

Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2010). Aggression. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 833–863). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302 (5643), 290–292.

Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293 (5537), 2105–2108.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33 (2–3), 61–83.

Lieberman, M. D., Hariri, A., Jarcho, J. M., Eisenberger, N. I., & Bookheimer, S. Y. (2005). An fMRI investigation of race-related amygdala activity in African-American and Caucasian-American individuals. Nature Neuroscience, 8 (6), 720–722.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2011, June 13). Public skepticism of psychology: Why many people perceive the study of human behavior as unscientific. American Psychologist. doi: 10.1037/a0023963

Meier, B. P., Robinson, M. D., & Wilkowski, B. M. (2006). Turning the other cheek: Agreeableness and the regulation of aggression-related crimes. Psychological Science, 17 (2), 136–142.

Morewedge, C. K., Gray, K., & Wegner, D. M. (2010). Perish the forethought: Premeditation engenders misperceptions of personal control. In R. R. Hassin, K. N. Ochsner, & Y. Trope (Eds.), Self-control in society, mind, and brain (pp. 260–278). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ochsner, K. N., Bunge, S. A., Gross, J. J., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2002). Rethinking feelings: An fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14 (8), 1215–1229

Preston, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2007). The eureka error: Inadvertent plagiarism by misattributions of effort. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 (4), 575–584.

Richeson, J. A., Baird, A. A., Gordon, H. L., Heatherton, T. F., Wyland, C. L., Trawalter, S., Richeson, J. A., Baird, A. A., Gordon, H. L., Heatherton, T. F., Wyland, C. L., Trawalter, S., et al.#8230;Shelton, J. N. (2003). An fMRI investigation of the impact of interracial contact on executive function. Nature Neuroscience, 6 (12), 1323–1328.

Media Attributions

- “ EEG cap ” by Thuglas is licensed under a CC0 1.0 licence.

- “ FMRI BOLD activation in an emotional Stroop task ” by Shima Ovaysikia, Khalid A. Tahir, Jason L. Chan and Joseph F. X. DeSouza is licensed under a CC BY 2.5 licence.

- “ Varian4T ” by A314268 is licensed under a CC0 1.0 licence.

Based on the collection and systematic analysis of observable data.

The tendency to think that we could have predicted something that we probably would not have been able to predict.

Characteristics that we are trying to measure.

particular method that we use to measure a variable of interest

Measures in which individuals are asked to respond to questions posed by an interviewer or on a questionnaire.

Measures designed to directly assess what people do.

A technique that records the electrical activity produced by the brain’s neurons through the use of electrodes that are placed around the research participant’s head.

Neuroimaging technique that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain structure and function.

Research that involves making observations of behavior and recording those observations in an objective manner.

Specific prediction about the relationship between the variables of interest and about the specific direction of that relationship.

That the outcome of the research can demonstrate empirically either that there is support for the hypothesis (i.e., the relationship between the variables was correctly specified) or that there is actually no relationship between the variables or that the actual relationship is not in the direction that was predicted.

Search for and test hypotheses about the relationships between two or more variables.

Used to summarize the association, or correlation, between two variables.

Variables that are not part of the research hypothesis but that cause both the predictor and the outcome variable and thus produce the observed correlation between them.

Research designs that include the manipulation of a given situation or experience for two or more groups of individuals who are initially created to be equivalent, followed by a measurement of the effect of that experience.

The situation that is created by the experimenter through the experimental manipulations.

The variable that is measured after the manipulations have occurred.

Determining separately for each participant which condition he or she will experience through a random process,

The extent to which changes in the dependent variable in an experiment can confidently be attributed to changes in the independent variable.

Are experimental research studies that are conducted in a natural environment,

Experimental designs that have two or more independent variables.

A false statement of what the research was really about.

A person who is actually part of the experimental team but who pretends to be another participant in the study.

The extent to which relationships can be expected to hold up when they are tested again in different ways and for different people. Science relies primarily upon replication—that is, the repeating of research.

A statistical procedure in which the results of existing studies are combined to determine what conclusions can be drawn on the basis of all the studies considered together.

Principles of Social Psychology - 1st International H5P Edition by Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Psychology Research Guide

Social psychology.

Social psychologists study the influence of social perception and interaction on individual and group behavior. The following resources can help you narrow your topic, learn about the language used to describe psychology topics, and get you up to speed on the major advancements in this field.

- Social Psychology search results on the American Psychological Association's website This link opens in a ne

Social Psychology Databases

Research in social psychology utilizes core psychology resources, as well as resources in communication and sociology. You may find it helpful to search the following databases for your social psychology topics or research questions, in addition to the core resources listed on the home page.

Social Psychology Subject Headings

You may find it helpful to take advantage of predefined subjects or subject headings in Shapiro Databases. These subjects are applied to articles and books by expert catalogers to help you find materials on your topic. Learn more about subject searching:

- Subject Searching

Consider using databases to perform subject searches, or incorporating words from applicable subjects into your keyword searches. Here are some social psychology subjects to consider:

- personality

- social psychology

- social anxiety

- social influence

Social Psychology Example Search

Not sure what you want to research exactly, but want to get a feel for the resources available? Try the following search in any of the databases listed above:

(behavioral OR social) AND Psych*

There isn't just one accepted word for this area of psychology, so we use OR boolean operators to tell the database any of the listed terms are relevant to our search. We use parenthesis to organize our search, and we stem or truncate the word psychology with the asterisk to tell the database that any ending of the word, as long as the letters psych are at the beginning of the word, will do. This way, the word psychological and other related terms will also be included.

- Learn more about Boolean Operators/Boolean Searching

Social Psychology Organization Websites

- Association for Research in Personality This link opens in a new window The Association for Research in Personality is a scientific organization devoted to bringing together scholars whose research contributes to the understanding of personality structure, development, and dynamics.

- Personality Pedagogy This link opens in a new window

- Personality Project This link opens in a new window

- Society for Personality and Social Psychology This link opens in a new window The Society for Personality and Social Psychology, founded in 1974, is the world’s largest organization of social and personality psychologists. With over 7,500 members, SPSP strives to advance the science, teaching, and application of social and personality psychology. The mission of SPSP is to advance the science, teaching, and application of social and personality psychology. SPSP members aspire to understand individuals in their social contexts for the benefit of all people.

- Society of Experimental Social Psychology This link opens in a new window The Society of Experimental Social Psychology (SESP) is a scientific organization dedicated to the advancement of social psychology.

- << Previous: Mental Health

- Next: Conducting Psychological Research >>

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.4: Research Methods in Social Psychology

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10665

- https://nobaproject.com/ via The Noba Project

Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Social psychologists are interested in the ways that other people affect thought, emotion, and behavior. To explore these concepts requires special research methods. Following a brief overview of traditional research designs, this module introduces how complex experimental designs, field experiments, naturalistic observation, experience sampling techniques, survey research, subtle and nonconscious techniques such as priming, and archival research and the use of big data may each be adapted to address social psychological questions. This module also discusses the importance of obtaining a representative sample along with some ethical considerations that social psychologists face.

learning objectives

- Describe the key features of basic and complex experimental designs.

- Describe the key features of field experiments, naturalistic observation, and experience sampling techniques.

- Describe survey research and explain the importance of obtaining a representative sample.

- Describe the implicit association test and the use of priming.

- Describe use of archival research techniques.

- Explain five principles of ethical research that most concern social psychologists.

Introduction

Are you passionate about cycling? Norman Triplett certainly was. At the turn of last century he studied the lap times of cycling races and noticed a striking fact: riding in competitive races appeared to improve riders’ times by about 20-30 seconds every mile compared to when they rode the same courses alone. Triplett suspected that the riders’ enhanced performance could not be explained simply by the slipstream caused by other cyclists blocking the wind. To test his hunch, he designed what is widely described as the first experimental study in social psychology (published in 1898!)—in this case, having children reel in a length of fishing line as fast as they could. The children were tested alone, then again when paired with another child. The results? The children who performed the task in the presence of others out-reeled those that did so alone.

Although Triplett’s research fell short of contemporary standards of scientific rigor (e.g., he eyeballed the data instead of measuring performance precisely; Stroebe, 2012), we now know that this effect, referred to as “ social facilitation ,” is reliable—performance on simple or well-rehearsed tasks tends to be enhanced when we are in the presence of others (even when we are not competing against them). To put it another way, the next time you think about showing off your pool-playing skills on a date, the odds are you’ll play better than when you practice by yourself. (If you haven’t practiced, maybe you should watch a movie instead!)

Research Methods in Social Psychology

One of the things Triplett’s early experiment illustrated is scientists’ reliance on systematic observation over opinion, or anecdotal evidence . The scientific method usually begins with observing the world around us (e.g., results of cycling competitions) and thinking of an interesting question (e.g., Why do cyclists perform better in groups?). The next step involves generating a specific testable prediction, or hypothesis (e.g., performance on simple tasks is enhanced in the presence of others). Next, scientists must operationalize the variables they are studying. This means they must figure out a way to define and measure abstract concepts. For example, the phrase “perform better” could mean different things in different situations; in Triplett’s experiment it referred to the amount of time (measured with a stopwatch) it took to wind a fishing reel. Similarly, “in the presence of others” in this case was operationalized as another child winding a fishing reel at the same time in the same room. Creating specific operational definitions like this allows scientists to precisely manipulate the independent variable , or “cause” (the presence of others), and to measure the dependent variable , or “effect” (performance)—in other words, to collect data. Clearly described operational definitions also help reveal possible limitations to studies (e.g., Triplett’s study did not investigate the impact of another child in the room who was not also winding a fishing reel) and help later researchers replicate them precisely.

Laboratory Research

As you can see, social psychologists have always relied on carefully designed laboratory environments to run experiments where they can closely control situations and manipulate variables (see the NOBA module on Research Designs for an overview of traditional methods). However, in the decades since Triplett discovered social facilitation, a wide range of methods and techniques have been devised, uniquely suited to demystifying the mechanics of how we relate to and influence one another. This module provides an introduction to the use of complex laboratory experiments, field experiments, naturalistic observation, survey research, nonconscious techniques, and archival research, as well as more recent methods that harness the power of technology and large data sets, to study the broad range of topics that fall within the domain of social psychology. At the end of this module we will also consider some of the key ethical principles that govern research in this diverse field.

The use of complex experimental designs , with multiple independent and/or dependent variables, has grown increasingly popular because they permit researchers to study both the individual and joint effects of several factors on a range of related situations. Moreover, thanks to technological advancements and the growth of social neuroscience , an increasing number of researchers now integrate biological markers (e.g., hormones) or use neuroimaging techniques (e.g., fMRI) in their research designs to better understand the biological mechanisms that underlie social processes.

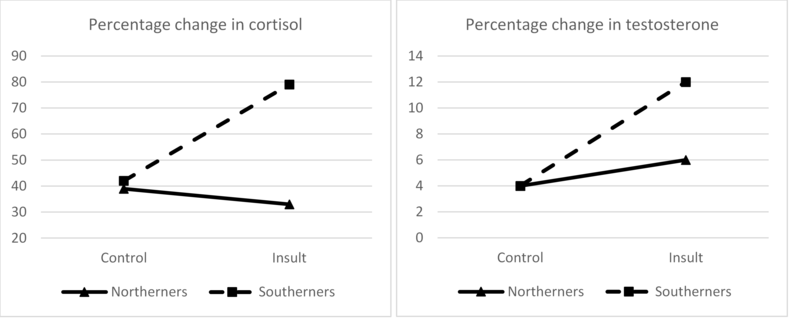

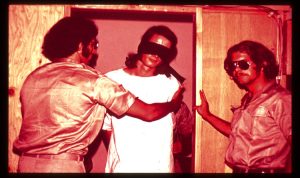

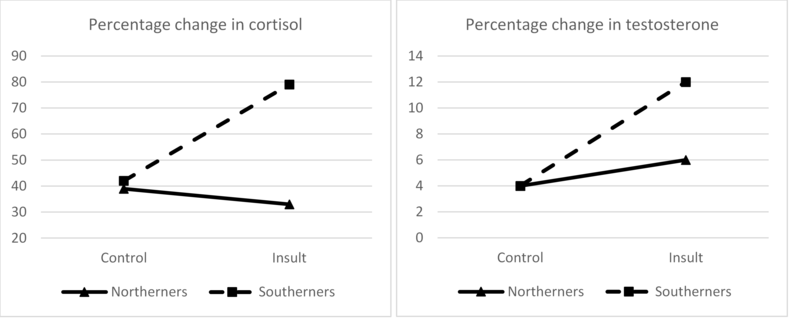

We can dissect the fascinating research of Dov Cohen and his colleagues (1996) on “culture of honor” to provide insights into complex lab studies. A culture of honor is one that emphasizes personal or family reputation. In a series of lab studies, the Cohen research team invited dozens of university students into the lab to see how they responded to aggression. Half were from the Southern United States (a culture of honor) and half were from the Northern United States (not a culture of honor; this type of setup constitutes a participant variable of two levels). Region of origin was independent variable #1. Participants also provided a saliva sample immediately upon arriving at the lab; (they were given a cover story about how their blood sugar levels would be monitored over a series of tasks).

The participants completed a brief questionnaire and were then sent down a narrow corridor to drop it off on a table. En route, they encountered a confederate at an open file cabinet who pushed the drawer in to let them pass. When the participant returned a few seconds later, the confederate, who had re-opened the file drawer, slammed it shut and bumped into the participant with his shoulder, muttering “asshole” before walking away. In a manipulation of an independent variable—in this case, the insult—some of the participants were insulted publicly (in view of two other confederates pretending to be doing homework) while others were insulted privately (no one else was around). In a third condition—the control group—participants experienced a modified procedure in which they were not insulted at all.

Although this is a fairly elaborate procedure on its face, what is particularly impressive is the number of dependent variables the researchers were able to measure. First, in the public insult condition, the two additional confederates (who observed the interaction, pretending to do homework) rated the participants’ emotional reaction (e.g., anger, amusement, etc.) to being bumped into and insulted. Second, upon returning to the lab, participants in all three conditions were told they would later undergo electric shocks as part of a stress test, and were asked how much of a shock they would be willing to receive (between 10 volts and 250 volts). This decision was made in front of two confederates who had already chosen shock levels of 75 and 25 volts, presumably providing an opportunity for participants to publicly demonstrate their toughness. Third, across all conditions, the participants rated the likelihood of a variety of ambiguously provocative scenarios (e.g., one driver cutting another driver off) escalating into a fight or verbal argument. And fourth, in one of the studies, participants provided saliva samples, one right after returning to the lab, and a final one after completing the questionnaire with the ambiguous scenarios. Later, all three saliva samples were tested for levels of cortisol (a hormone associated with stress) and testosterone (a hormone associated with aggression).

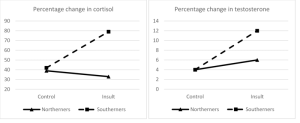

The results showed that people from the Northern United States were far more likely to laugh off the incident (only 35% having anger ratings as high as or higher than amusement ratings), whereas the opposite was true for people from the South (85% of whom had anger ratings as high as or higher than amusement ratings). Also, only those from the South experienced significant increases in cortisol and testosterone following the insult (with no difference between the public and private insult conditions). Finally, no regional differences emerged in the interpretation of the ambiguous scenarios; however, the participants from the South were more likely to choose to receive a greater shock in the presence of the two confederates.

Field Research

Because social psychology is primarily focused on the social context—groups, families, cultures—researchers commonly leave the laboratory to collect data on life as it is actually lived. To do so, they use a variation of the laboratory experiment, called a field experiment . A field experiment is similar to a lab experiment except it uses real-world situations, such as people shopping at a grocery store. One of the major differences between field experiments and laboratory experiments is that the people in field experiments do not know they are participating in research, so—in theory—they will act more naturally. In a classic example from 1972, Alice Isen and Paula Levin wanted to explore the ways emotions affect helping behavior. To investigate this they observed the behavior of people at pay phones (I know! Pay phones! ). Half of the unsuspecting participants (determined by random assignment ) found a dime planted by researchers (I know! A dime! ) in the coin slot, while the other half did not. Presumably, finding a dime felt surprising and lucky and gave people a small jolt of happiness. Immediately after the unsuspecting participant left the phone booth, a confederate walked by and dropped a stack of papers. Almost 100% of those who found a dime helped to pick up the papers. And what about those who didn’t find a dime? Only 1 out 25 of them bothered to help.

In cases where it’s not practical or ethical to randomly assign participants to different experimental conditions, we can use naturalistic observation —unobtrusively watching people as they go about their lives. Consider, for example, a classic demonstration of the “ basking in reflected glory ” phenomenon: Robert Cialdini and his colleagues used naturalistic observation at seven universities to confirm that students are significantly more likely to wear clothing bearing the school name or logo on days following wins (vs. draws or losses) by the school’s varsity football team (Cialdini et al., 1976). In another study, by Jenny Radesky and her colleagues (2014), 40 out of 55 observations of caregivers eating at fast food restaurants with children involved a caregiver using a mobile device. The researchers also noted that caregivers who were most absorbed in their device tended to ignore the children’s behavior, followed by scolding, issuing repeated instructions, or using physical responses, such as kicking the children’s feet or pushing away their hands.

A group of techniques collectively referred to as experience sampling methods represent yet another way of conducting naturalistic observation, often by harnessing the power of technology. In some cases, participants are notified several times during the day by a pager, wristwatch, or a smartphone app to record data (e.g., by responding to a brief survey or scale on their smartphone, or in a diary). For example, in a study by Reed Larson and his colleagues (1994), mothers and fathers carried pagers for one week and reported their emotional states when beeped at random times during their daily activities at work or at home. The results showed that mothers reported experiencing more positive emotional states when away from home (including at work), whereas fathers showed the reverse pattern. A more recently developed technique, known as the electronically activated recorder , or EAR, does not even require participants to stop what they are doing to record their thoughts or feelings; instead, a small portable audio recorder or smartphone app is used to automatically record brief snippets of participants’ conversations throughout the day for later coding and analysis. For a more in-depth description of the EAR technique and other experience-sampling methods, see the NOBA module on Conducting Psychology Research in the Real World.

Survey Research

In this diverse world, survey research offers itself as an invaluable tool for social psychologists to study individual and group differences in people’s feelings, attitudes, or behaviors. For example, the World Values Survey II was based on large representative samples of 19 countries and allowed researchers to determine that the relationship between income and subjective well-being was stronger in poorer countries (Diener & Oishi, 2000). In other words, an increase in income has a much larger impact on your life satisfaction if you live in Nigeria than if you live in Canada. In another example, a nationally-representative survey in Germany with 16,000 respondents revealed that holding cynical beliefs is related to lower income (e.g., between 2003-2012 the income of the least cynical individuals increased by $300 per month, whereas the income of the most cynical individuals did not increase at all). Furthermore, survey data collected from 41 countries revealed that this negative correlation between cynicism and income is especially strong in countries where people in general engage in more altruistic behavior and tend not to be very cynical (Stavrova & Ehlebracht, 2016).