Advertisement

Long-Term Dynamics of Neighborhoods and Crime: The Role of Education Over 40 Years

- Original Paper

- Published: 01 October 2021

- Volume 39 , pages 187–249, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Adam Boessen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5907-327X 1 ,

- Marisa Omori 1 &

- Claire Greene 1

1047 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 09 November 2021

This article has been updated

Over the last 40 years, considerable changes have occurred in both education and crime, and in this study, we examine the longer-term consequences of education for violence in communities. We argue that the impact of education on crime depends on the temporal and spatial context of educational levels. Specifically, we focus on whether the type of educational attainment matters and the broader historical context. We also examine whether these patterns are robust for different regions of the city and racial/ethnic compositions of neighborhoods.

Using longitudinal neighborhood data over 40 years in St. Louis, Missouri, we test whether education has consequences for violent crime with a series of two-way fixed effects models.

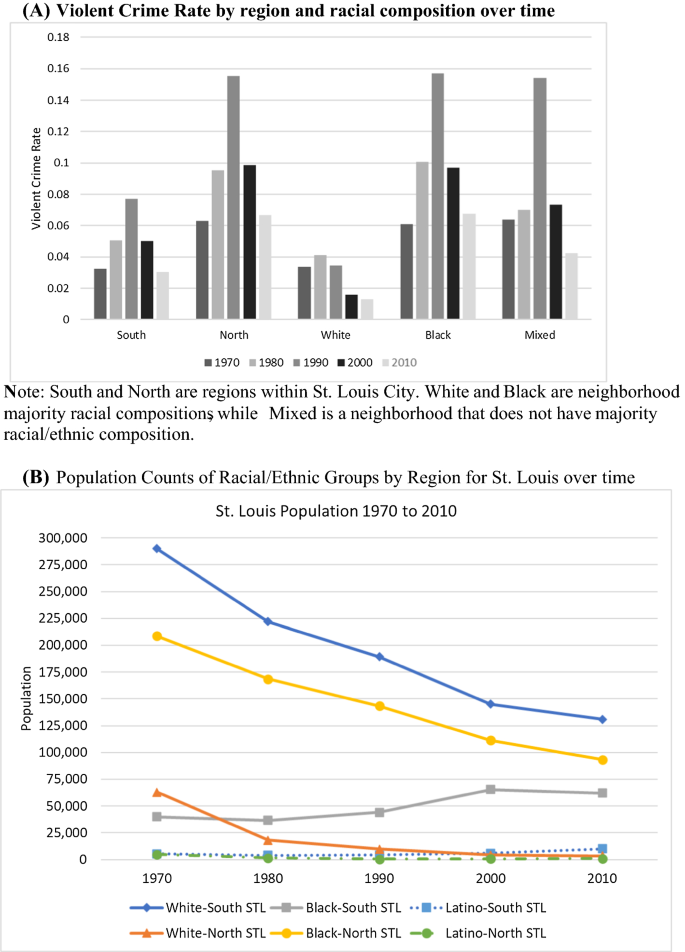

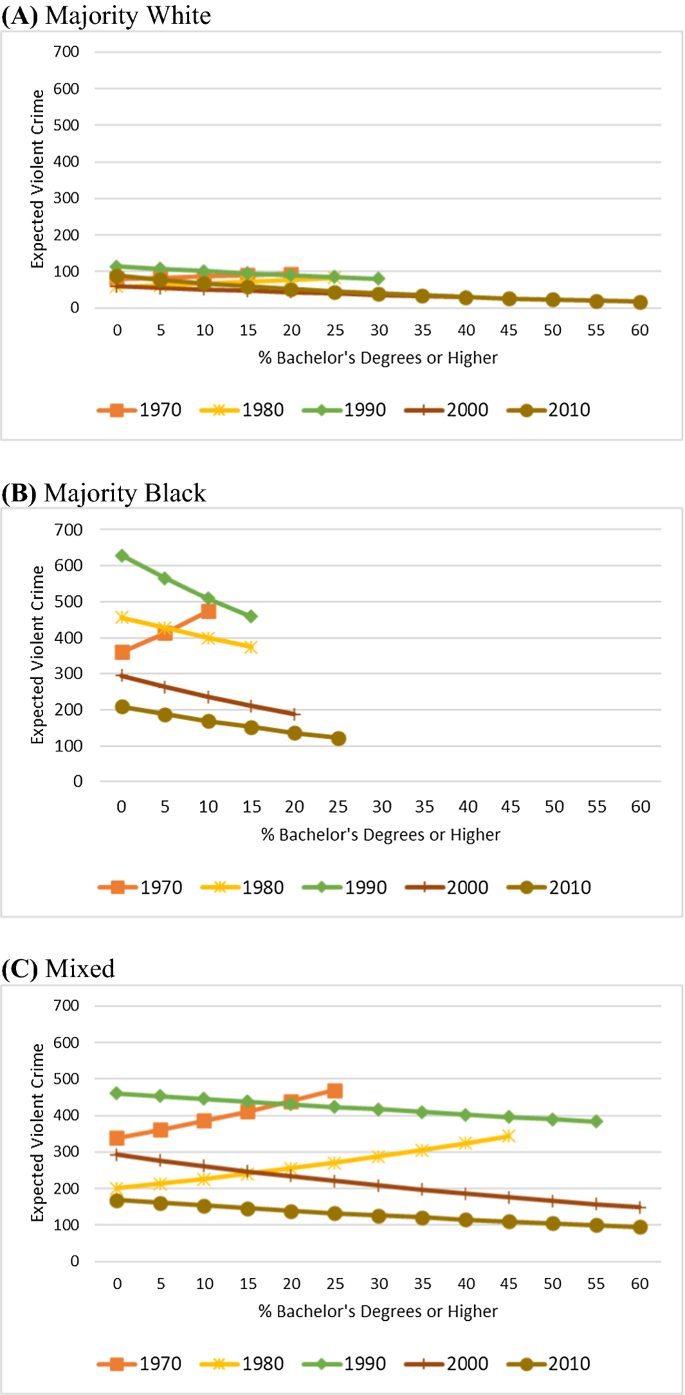

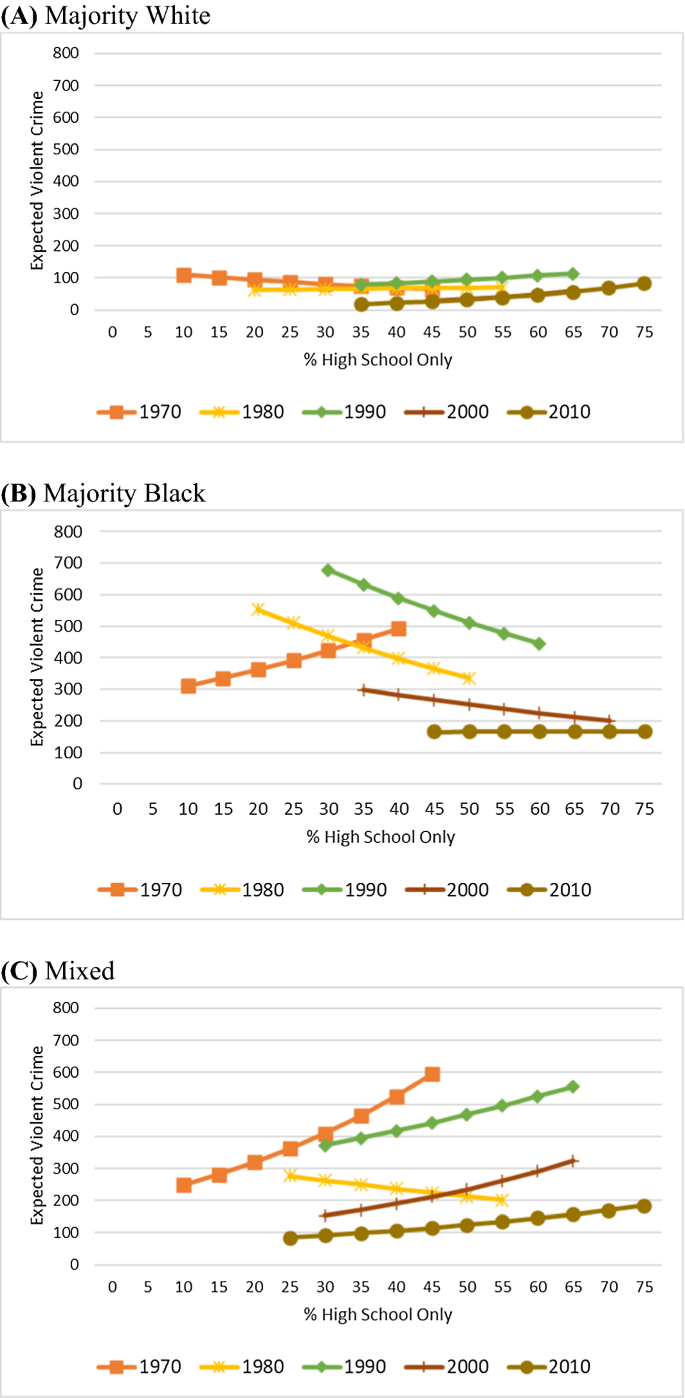

Neighborhoods with more college degrees in more recent time periods are generally associated with reductions in violent crime, especially in the white, southern region of the city. In contrast, neighborhoods with greater reliance on high school degrees were associated with violence reduction in the past, especially in the Black, northern part of the city, but the relationship no longer holds in the modern era. Both time and place therefore matter for education’s association with crime in neighborhoods.

The findings provide evidence that educational attainment has important consequences for neighborhood crime, but this relationship depends on the kind of education, historical temporal period, and region of the city. Overall, communities with more college degrees are consistently associated with reductions in violence in more recent decades.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Do schools cause crime in neighborhoods evidence from the opening of schools in philadelphia.

John M. MacDonald, Nancy Nicosia & Benjamin David Ukert

Neighborhood Effects on Crime. Evidence from America’s Moving to Opportunity Experiment

Inequality and crime revisited: effects of local inequality and economic segregation on crime.

Songman Kang

Change history

09 november 2021.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09537-2

Nevertheless, a challenge has emerged in the literature in regards to these systemic and social disorganization theories of neighborhood crime, which suggest that poor communities are organized (e.g., see Sánchez-Jankowski 2008 ; Whyte 1943 ), and other work argues that many places with strong kin and friendship ties can also have higher crime rates (Pattillo 1998 ; Sampson 2012 ).

Moreover, even amongst different kinds of universities (public vs. private), there is evidence of inequality in the spatial distribution of social friendships among students who attend schools (e.g., private school students often have a much broader spatial footprint in where students come from who attend, see Spiro et al. 2016 ).

We use 2005–2009 ACS data rather than the 2010 census since the ACS data are already in year 2000 tracts.

Census tracts are also a useful approach since neighborhood census data are not available in micro units at earlier decades but tract data is available, and tracts’ boundaries can be standardized between decades.

As of the 2000 census, there were 113 tracts for St. Louis, but four census tracts had zero population or low population (e.g., a tract with a large cemetery) and were omitted from the analyses. We use the same analytical sample for St. Louis that Peterson and Krivo 2010 used in their study. The sample sizes in the tables are 544 rather than 545, and this is because one tract in 1970 had missing data, and this observation was omitted from the analysis.

Specifically, blocks are mostly contained within the named neighborhoods, although tracts are relatively similar too. We first intersected the blocks with the named neighborhoods in ArcGIS, and we then merged in the block population data, and used it to apportion the crime data. To assess this procedure, we used our crime data from 2010 that has x–y coordinates. We put our 2010 data into the named neighborhood units and apportioned them into year 2000 units. As a comparison, we used the x–y coordinates of the 2010 crime data and aggregated them directly to 2000 census tracts. We then correlated the violent crime measures using the apportioned units and the crime data aggregated directly to 2000 census tracts. The correlation was .93, which suggests that this apportionment approach is reasonable.

As an assessment of the quality of these data, we compared the distributions of the counts of crime at each decade with the reported Uniform Crime Reports that are available at the city level for each time point. All data were quite similar with the reported uniform crime report data, and this gives us confidence in the quality of these data. Of course, these data also are subject to the issues of official police data with not all crimes being reported or recorded (Lynch and Addington 2007 ; MacDonald 2001 ). Yet, Baumer ( 2002 ) noted that these reporting practices are not related systematically to neighborhood characteristics, therefore suggesting that the coefficients are unbiased. We also do not focus on rape or sexual assault given well-known issues with this crime type.

We tested whether there were crime type differences amongst the different crime categories of violent crime by estimating separate models for homicide, aggravated assault, and robbery. The results were nearly identical and given the abundance of tables, we only show the results for our general measure of violent crime. Future research might also examine the consequences of education for other types of crime (i.e., property crime), as well as heterogeneity within various crime types (Kubrin and Herting 2003 ; Kubrin and Weitzer 2003 ).

For 1970 and 1980, the census asked about the number of years of school each person completed (e.g., high school 1 year, high school 2 years, high school 3 years, etc.). For 1990, 2000, and 2010, the census question changed to reflect the level of school completed and type of degree. For the 1970 and 1980 census, we follow the Census’ approach to compare educational attainment over time by only focusing on high school for 4 years completed (or higher) or college degree 4 years (or higher). While some prior work has examined ‘years of education’ (e.g. See Lafree et al. 1992 ), we do not use this approach for a few reasons. First, the census does not ask about years of education in 1990, 2000, or 2010, and abandoned this practice for the 1990 census (see Kominski and Adams 1994 ; Kominski and Siegel 1993 ). Second, we are primarily interested in the qualitative distinction and credential of a college degree (not number of years educated), and this implies nonlinear (categorical) change. Third, many students, particularly in the modern era, likely go to school for many years (e.g., 5 years to obtain a college degree) or part time, and thus they may have more years of education but without a degree, suggesting more measurement error if we used this approach.

As another approach, some research has created an economic disadvantage factor. We did not use this approach because we are interested in within neighborhood change over time, and thus we would be comparing relative standardized within unit changes over time. As such, these analyses would allow for possibility that changes in other neighborhoods driving some of the within unit change. Thus, a neighborhood could appear to be changing simply because of its position in the distribution of a neighborhood factor score. It is also more conceptually challenging to interpret over time, and there are few measures available to compute over the 40 year time period. We did test some ancillary models that created a factor score with poverty, unemployment, and single parent families, and the inclusion of this measure did not alter our main findings, giving us further confidence in our models. Finally, we also estimated models using only unemployment, and the results were substantively the same.

For 1970, the heterogeneity measure is only based on 4 categories since there is not a measure of the percent Asian in the Census for this decade. This group is thus combined with the other category.

Rather than focusing on heterogeneity, another approach would include measures of individual racial/ethnic groups. We tested this possibility, and given that Black and white residents are by far the largest groups in St. Louis, we estimated a series of ancillary models that included the % Black residents. The results were the same, and the % Black measure was not significant for any of the models. We also note that this measure is correlated with our disadvantage measure (.76 on average over time), and overall, this gives us further confidence in our results. Finally, We also test models in the paper that examine differences by racial/ethnic composition of the neighborhood.

Recent work on immigration shows it is protective for communities, particularly during the 1990’s crime decline (Martinez et al. 2010 ; Ousey and Kubrin 2018 ). One explanation for these findings would suggest that they are due in part to high educational achievement among many immigrants, and thus we control for immigration.

We account for the binning nature of the data (i.e., the census only asks about income categories) using the Pareto-linear procedure with the prln04.exe program (Nielsen and Alderson 1997). This measure is correlated with poverty on average over decades at .23.

We also estimated a series of ancillary models that did not include neighborhoods with less than 1000 residents. The results from these models were essentially identically to the models shown in the tables.

The random effects model is another approach to understanding change in neighborhoods over time, and this approach theoretically would be quite different since it assesses differences between neighborhoods. While we think this is an interesting research question, our focus is on within neighborhood change and the fixed effects have the added benefit of accounting for time stable unobservables. Nonetheless, we did perform as Hausman test that allows for testing systematic differences between random and fixed effects models. The test was significant, suggesting that fixed effects is both theoretically and empirically the better approach.

As ancillary models, we also estimated multilevel mixed effects models that included random effects for neighborhoods and time. For these models, we included a random intercept for each neighborhood and the effect of time was allowed to vary across each neighborhood as a random slope. The results from these models were substantively the same as those presented in the text, which further strengthens our findings.

It is well-known that Stata’s “xtnbreg, fe” command is not a true fixed effects model, and one approach to estimate fixed effects is to use dummy variables (Allison 2009 ). One challenge with this approach is what is often referred to as the ‘incidental parameters problem’. To assess this issue, we estimated models without using neighborhood dummy variables, but we included our neighborhood entity fixed effects through Stata’s estimation commands (i.e., xtpoisson, fe) and added time dummies, and the results were substantively the same, giving us further confidence in the results.

As another set of ancillary models, we included a lagged violent crime rate with all of our models. This measure did not alter the substantive pattern of results, and this further strengthens our findings.

We also tested models with a 65% majority threshold and the results were similar.

Other researchers have used a similar modeling strategy when using states as units to understand punishment over decades (Campbell et al. 2015 ; Greenberg and West 2001 ; Jacobs and Carmichael 2001 ). We did estimate ancillary models for each decade separately and the results were similar. Also, we note that one study used time series models of crime trends in cities from 1960’s to 2000 suggests that there is little evidence that crime trends are historically contingent (LaFree 1999 ; McDowall 2002 ; McDowall and Loftin 2005 ; see also Parker et al. 2017 ). We are not aware of any research to date that has examined the historically contingent nature of different neighborhood predictors on crime.

To study neighborhoods or micro places over time, some studies have employed group based trajectory models (Stults 2010 ; Weisburd et al. 2004 ). While this approach is reasonable for some research questions (see also Bauer 2007 ; Bollen and Brand 2010 ; Kreager et al. 2011 ; Martinez et al. 2010 ; Nagin and Tremblay 2005 ), we are interested in within neighborhood processes, but the studies that employ those trajectory models nearly always focus on between neighborhood differences in the types of trajectories. The group based trajectory models employed most often in the literature also do not account for potentially important time stable unobserved characteristics (which we do with our fixed effects), as well as baseline differences among neighborhoods. Finally, the fixed effects models allow for easily testing differences between discrete historical contexts. We are aware of no work testing period change with group based trajectory models in that the change is assumed to operate in the same way across the entire time period of study. In this paper, we explicitly test whether neighborhoods experienced a discrete change in different decades for education.

Collinearity was tested with Philip Ender’s Stata ado file: ‘collin’. All variance inflation factors were under 4, thus there is no evidence of an issue in regards to collinearity. We tested for outliers using studentized residuals from models estimated as linear regressions (the outcome was converted to a rate). We then estimated models without observations with studentized residuals greater than or less than 2, and the results were the same.

One possibility for future research is that many of the high crime neighborhoods are located on the boundary (Delmar Blvd) separating the north and south regions of St. Louis. As such, the position of a neighborhood within a region in tandem with the placement of boundaries may be important for crime patterns.

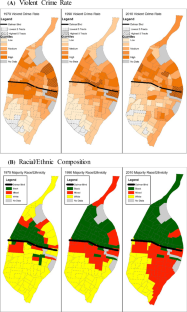

As one comparison between the map for violent crime (Fig. 1 A) and racial/ethnic composition (Fig. 1 B), as well as considering the average plots in “Appendix Fig. 7 ”, we see that Black and mixed neighborhoods generally have higher crime rates than white neighborhoods on average. But, the cold spots on the extreme end of the distribution are always in white neighborhoods over time, while the ‘hot spots’ are most often in majority white neighborhoods in the 1970’s, but in more recent decades they are located in majority Black or mixed neighborhoods. Moreover, many of the cold spots are largely surrounded by other white neighborhoods, while the Black and mixed neighborhood hot spots are often sharing a border between different racial/ethnic compositions (i.e., Black neighborhoods next to white neighborhoods or mixed neighborhoods next to Black neighborhoods), suggesting future research more explicitly consider these patterns as a part of a larger socio spatial process (see also Boessen and Hipp 2015 ). Further, some of the areas with no population near downtown (i.e., railroad tracks) and key road boundaries (i.e., Delmar Blvd.) effectively shape high crime hot spots.

As noted in Appendix, the correlation between poverty and bachelor’s degrees is − .19, suggesting these while correlated as would be expected, it is relatively modest.

Because the regions are time-invariant, these differences were previously differenced out in our fixed effects models (see also Bollen and Brand 2010 ). Although not shown in the tables, we estimated ancillary models that included interactions between region and each decade timepoint to assess whether the regions were statistically different over time in their consequences for crime. These models indicated that the most recent decades (2000 and 2010) were significantly different from earlier decades (1970, 1980, and 1990), suggesting that we are theoretically and empirically justified in assessing differences by region. As another approach, we removed both sets of fixed effects from the models, and estimated separate models for each timepoint. With these models we could include our indicator for region, and it was significant in all of the models. We also tested these models with indicators for various racial compositions of neighborhoods with a series of N-1 dummy variables (white, Black, or mixed), and the results showed differences over time by racial composition of neighborhood. Taken as a whole, these ancillary models indicate we are theoretically and empirically justified for our models by region and racial/ethnic composition of neighborhood.

We also estimated models without racial/ethnic heterogeneity in the models, and the results were the same.

We show additional models with 1990 and 2010 as the reference groups in Appendix Tables 12 and 13 , comparing the third time point (i.e., the 1990’s) and the last time point (i.e., the 2010’s).

Although we are interested in each individual period effect, we used Stata’s ‘testparm’ command to jointly test each set of interactions as a Wald test (see also Paternoster et al. 1998 ). The result of these tests are consistent with the results presented, suggesting overall differences in the effects in different time periods.

We also briefly point out that these race/ethnicity majority neighborhood analyses are essentially comparisons between other similar (i.e., within group) neighborhoods (i.e., comparing white majority neighborhoods with other white majority neighborhoods), but this approach does allow for seeing their effect when plotted.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that there are only 5.2% (N = 11) mixed neighborhoods in 1970 and 12.8% (N = 14) in 1980, but this grows to 33% (N = 36) by 2010 and the crime rates in these areas are still relatively high when compared to white neighborhoods.

We also tested models using unemployment (rather than poverty), and the results were substantively similar.

We also tested whether high school degrees act as a mediator between poverty and violence, and there was no evidence of any indirect effects of poverty on violence being mediated by high school degrees.

We also estimated these models without the lagged violent crime measure, and the results were substantively the same.

The data are available at ICPSR: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/RCMD/studies/27501 .

Abbott A (2001) Time matters: on theory and method. University of Chicago, Chicago

Google Scholar

Adams RE (1992) Is happiness a home in the suburbs? The influence of urban versus suburban neighborhoods on psychological health. J Community Psychol 20(4):353–371

Article Google Scholar

Allison PD (2009) Fixed effects regression models. Vol. 160: SAGE Publications

Baltagi BH, Song SH, Koh W (2003) Testing panel data regression models with spatial error correlation. J Econom 117(1):123–150

Bauer DJ (2007) Observations on the use of growth mixture models in psychological research. Multivar Behav Res 42:757–786

Baumer EP (2002) Neighborhood disadvantage and police notification by victims of violence. Criminology 40(3):579–616

Baumer EP, Fowler C, Messner SF, Rosenfeld R (2021) Change in the spatial clustering of poor neighborhoods within U.S. counties and its impact on homicide: an analysis of metropolitan counties, 1980–2010. The Sociol Q, 1–25

Beckett K, Western B (2001) Governing social marginality: welfare, incarceration, and the transformation of state policy. Punishm Soc 3(1):43–59

Bellair PE (1997) Social interaction and community crime: examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology 35(4):677–703

Bennett PR (2011) The relationship between neighborhood racial concentration and verbal ability: An investigation using the institutional resources model. Soc Sci Res 40(4):1124–1141

Beyerlein K, Hipp JR (2006) From pews to participation: the effect of congregation activity and context on bridging civic engagement. Soc Probl 53(1):97–117

Boessen A, Hipp JR (2015) Close-ups and the scale of ecology: land uses and the geography of social context and crime. Criminology 53(3):399–426

Boessen A, Hipp JR, Butts CT, Nagle NN, Smith EJ (2017) The built environment, spatial scale, and social networks: Do land uses matter for personal network structure? Environ Plan B 45(3):400–416

Bollen KA, Brand JE (2010) A general panel model with random and fixed effects: a structural equations approach. Soc Forces 89(1):1–34

Burgess EW (1925) The growth of the city: an introduction to a research project. In: Park RE, Ernest WB, Roderick DM (eds), The city: suggestions for investigvation of human behavior in the urban environment. University of Chicago Press

Bursik RJ, Grasmick HG (1993) Neighborhoods & crime: the dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books, New York

Bursik RJ Jr, Webb J (1982) Community change and patterns of delinquency. Am J Sociol 88(1):24–42

Campbell MC, Vogel M, Williams J (2015) Historical contingencies and the evolving importance of race, violent crime, and region in explaining mass incarceration in the United States. Criminology 53(2):180–203

Carnevale AP, Strohl J, Melton M (2015) What’s it worth? Georgetown University: https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/whatsitworth-complete.pdf

Census Bureau (2010). https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed/tables/12s0229.pdf

Chetty R et al (2017) Mobility report cards: the role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. NBER Working Paper No. 23618

Chilton RJ (1964) Continuity in delinquency area research: a comparison of studies for Baltimore, Detroit, and Indianapolis. Am Sociol Rev 29(1):71–83

Crutchfield RD, Glusker A, Bridges GS (1999) A tale of three cities: labor markets and homicide. Sociol Focus 32(1):65–83

Deane G, Messner SF, Stucky TD, McGeever KF, Kubrin CE (2008) Not ‘islands, entire of themselves’: exploring the spatial context of city-level robbery rates. J Quant Criminol 24:363–380

DeSilver D (2018) For most workers, real wages have barely budged for decades. Pew Research Center: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/

Domina T (2006) Brain drain and brain gain: rising educational segregation in the United States, 1940–2000. City Community 5(4):387–407

Ehrenhalt A (2012) The great inversion and the future of the American city: Vintage

Elhorst JP (2003) Specification and estimation of spatial panel data models. Int Reg Sci Rev 26(3):244–268

Elhorst JP (2014) Spatial econometrics: from cross-sectional data to spatial panels. Springer, Berlin

Book Google Scholar

Ellen IG, Horn KM, Reed D (2019) Has falling crime invited gentrification? J Hous Econ 46:101636

Eller CC, DiPrete TA (2018) The paradox of persistence: explaining the black-white gap in bachelor’s degree completion. Am Sociol Rev 83(6):1171–1214

Elliott KC, Jones T (2021) Beyond dollars and cents. Obtained from: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/05/19/any-measure-value-higher-ed-must-take-account-advancement-social-justice-opinion

Elliott DS, Menard S, Rankin B, Elliott A, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D (2006) Good kids from bad neighborhoods: successful development in social context. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Farley JE (1995) Race still matters: the minimal role of income and housing cost as causes of housing segregation in St. Louis, 1990. Urban Aff Rev 31(2):244–254

Furtado K, Vargas C, Corbett L, Dwight D IV (2020) Still separate, still unequal: a call to level the uneven education playing field in St. Louis. Forward Through Ferguson. See http://stillunequal.org/files/FTF_StillUnequal_Report_2020_web.pdf

Gibbs JP, Martin WT (1962) Urbanization, technology, and the division of labor: international patterns. Am Sociol Rev 27(5):667–677

Gordon C (2009) Mapping decline: St. Louis and the fate of the American city. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Greenberg DF, West V (2001) State prison populations and their growth, 1971–1991. Criminology 39(3):615–654

Harlan C (2014) In St. Louis, Delmar Boulevard is the line that divides a city by race and perspective. Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/in-st-louis-delmar-boulevard-is-the-line-that-divides-a-city-by-race-and-perspective/2014/08/22/de692962-a2ba-4f53-8bc3-54f88f848fdb_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.8b8f66bd73c4

Hauser RM, Logan JA (1992) How not to measure intergenerational occupational persistence. Am J Sociol 97(6):1689–1711

Hillman NW (2016) Geography of college opportunity: the case of education deserts. Am Educ Res J 53(4):987–1021

Hipp JR (2007) Income inequality, race, and place: does the distribution of race and class within neighborhoods affect crime rates? Criminology 45(3):665–697

Hipp JR (2011) Violent crime, mobility decisions, and neighborhood racial/ethnic transition. Soc Probl 58(3):410–432

Hipp JR, Chamberlain AW (2015) Foreclosures and crime: a city-level analysis in Southern California of a dynamic process. Soc Sci Res 51:219–232

Hipp JR, Kane K (2017) Cities and the larger context: What explains changing levels of crime? J Crim Just 49:32–44

Hipp JR, Wickes R (2017) Violence in urban neighborhoods: a longitudinal study of collective efficacy and violent crime. J Quant Criminol 33:783–808

Hipp J, Yates D (2011) Ghettos, thresholds, and crime: Does concentrated poverty really have an accelerating increasing effect on crime? Criminology 49(4):955–990

Hirschfield PJ (2008) Preparing for prison? The criminalization of school discipline in the USA. Theor Criminol 12(1):79–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480607085795

Hirschfield PJ (2018) Schools and crime. Annu Rev Criminol 1(1):149–169

Hout M (2012) Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annu Rev Sociol 38(1):379–400

Hunter A (1975) The loss of community: an empirical test through replication. Am Sociol Rev 40(5):537–552

Hunter A (1985) Private, parochial and public social orders: the problem of crime and incivility in Urban communities. In Metropolis: Center and Symbol of Our Times, edited by P. Kasinitz. New York: New York University

Jacobs D, Carmichael JT (2001) The politics of punishment across time and space: a pooled time-series analysis of imprisonment rates. Soc Forces 80(1):61–89

Johnson O Jr (2010) Assessing neighborhood racial segregation and macroeconomic effects in the education of African Americans. Rev Educ Res 80(4):527–575

Kent SL, Jacobs D (2005) Minority threat and police strength from 1980 to 2000: a fixed-effects analysis of nonlinear and interactive effects in large U.S. Cities. Criminology 43(3):731–760

Kim J, Lee Y (2018) Does it take a school? Revisting the influence of first arrest on subsequent delinquency and educational attainment in a tolerant educational background. J Res Crime Delinq (Forthcoming)

Kohfeld CW, Sprague J (2006) Arrests as communications to criminals in St. Louis, 1970, 1972–1982: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor]

Kominski R, Andrea A (1994) Educational attainment in the United States: March 1993 and 1992. Current population reports. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC

Kominski R, Siegel PM (1993) Measuring education in the current population survey. Mon Labor Rev 116:34

Kreager D, Lyons CJ, Hays ZR (2011) Urban revitalization and seattle crime, 1982–2000. Soc Probl 58(4):615–639

Krivo LJ, Peterson RD, Kuhl DC (2009) Segregation, racial structure, and neighborhood violent crime. Am J Sociol 114(6):1765–1802

Krivo LJ, Washington HM, Peterson RD, Browning CR, Calder CA, Kwan M-P (2013) Social isolation of disadvantage and advantage: the reproduction of inequality in urban space. Soc Forces 92(1):141–164

Kubrin CE, Herting JR (2003) Neighborhood correlates of homicide trends: an analysis using growth-curve modeling. Sociol Q 44(3):329–350

Kubrin CE, Weitzer R (2003) Retaliatory homicide: concentrated disadvantage and neighborhood culture. Soc Probl 50(2):157–180

Kupchik A (2010) Homeroom security: school discipline in an age of fear, vol 6. NYU Press, New York

LaFree G (1999) Declining violent crime rates in the 1990s: predicting crime booms and busts. Annu Rev Sociol 25:145–168

LaFree G, Drass KA (1996) The effect of changes in intraracial income inequality and educational attainment on changes in arrest rates for African Americans and Whites, 1957–1990. Am Sociol Rev 61(4):614–634

LaFree G, Drass KA, O’Day P (1992) Race and crime in Postwar America: determinants of African-American and White Rates, 1957–1988. Criminology 30(2):158–185

LaFree G, Baumer EP, O’Brien R (2010) Still separate and unequal? A city-level analysis of the black-white gap in homicide arrests since 1960. Am Sociol Rev 75(1):75–100

Land KC, McCall PL, Cohen LE (1990) Structural covariates of homicide rates: Are there any invariances across time and social space? Am J Sociol 95(4):922–963

Lemieux T (2006) Postsecondary education and increasing wage inequality. Am Econ Rev 96(2):195–199

Levin A, Rosenfeld R, Deckard M (2017) The law of crime concentration: an application and recommendations for future research. J Quant Criminol 33:635–647

Levy BL (2018) Heterogeneous impacts of concentrated poverty during adolescence on college outcomes. Soc Forces 98(1):147–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy116

Levy BL, Owens A, Sampson RJ (2019) The varying effects of neighborhood disadvantage on college graduation: moderating and mediating mechanisms. Sociol Educ 92(3):269–292

Light MT, Thomas JT (2019) Segregation and violence reconsidered: Do whites benefit from residential segregation? Am Sociol Rev 84(4):690–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419858731

Light MT, Ulmer JT (2016) Explaining the gaps in white, black, and Hispanic violence since 1990 accounting for immigration, incarceration, and inequality. Am Sociol Rev 81(2):290–315

Lochner L, Moretti E (2004) The effect of education on crime: evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. Am Econ Rev 94(1):155–189

Logan JR, Stults BJ (2011) The persistence of segregation in the metropolis: New findings from the 2010 census. Census brief prepared for Project US2010

Logan JR, Zhang W, Chunyu MD (2015) Emergent Ghettos: black neighborhoods in New York and Chicago, 1880–1940. Am J Sociol 120(4):1055–1094

Lynch JP, Addington LA (eds) (2007) Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and UCR. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

MacDonald Z (2001) Revisiting the dark figure. Br J Criminol 41(1):127–149

Machin S, Marie O, Vujić S (2011) The crime reducing effect of education. Econ J 121(552):463–484

Martinez R, Stowell JI, Lee MT (2010) Immigration and crime in an era of transformation: a longitudinal analysis of homicides in San Diego Neighborhoods, 1980–2000*. Criminology 48(3):797–829

Martinez R, Stowell JI, Iwama JA (2016) The role of immigration: race/ethnicity and San Diego homicides since 1970. J Quant Criminol 32(3):471–488

Massey DS (1994) Getting away with murder: segregation and violent crime in urban America. U Pa l Rev 143:1203

McDonald S (2011) What’s in the “old boys” network? Accessing social capital in gendered and racialized networks. Soc Netw 33(4):317–330

McDowall D (2002) Tests of nonlinear dynamics in U.S. homicide time series, and their implications. Criminology 40(3):711–736

McDowall D, Loftin C (2005) Are U.S. crime rate trends historically contingent? J Res Crime Delinq 42(4):359–383

McKinnish T, Walsh R, Kirk White T (2010) Who Gentrifies low-income neighborhoods? J Urban Econ 67(2):180–193

Metzger MW, Fowler PJ, Swanstrom T (2018) Hypermobility and educational outcomes: the case of St. Louis. Urban Educ 53(6):774–805

Millo G, Piras G (2012) splm: spatial panel data models in R. J Stat Softw 47(1):1–38

Morris M (2016) Pushout: the criminalization of Black girls in schools. The New Press, New York

Nagin DS, Tremblay RE (2005) From seduction to passion: a response to Sampson and Laub. Criminology 43(4):915–918

Neil R, Sampson RJ (2021) The birth lottery of history: arrest over the life course of multiple cohorts coming of age, 1995–2018. Am J Sociol 126(5):1127–1178

Nordin M (2017) Does eligibility for tertiary education affect crime rates? Quasi-experimental evidence. J Quant Criminol (Forthcoming)

Ousey GC, Kubrin CE (2018) Immigration and crime : assessing a contentious issue. Annu Rev Criminol 1

Papachristos AV, Smith CM, Scherer ML, Fugiero MA (2011) More coffee, less crime? The relationship between gentrification and neighborhood crime rates in Chicago, 1991 to 2005. City Community 10(3):215–240

Parker K (2008) Unequal crime decline: theorizing race, urban inequality, and criminal violence. New York University Press, New York

Parker KF, Mancik A, Stansfield R (2017) American crime drops: investigating the breaks, dips and drops in temporal homicide. Soc Sci Res 64:154–170

Parks-Yancy R (2006) The effects of social group membership and social capital resources on careers. J Black Stud 36(4):515–545

Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A (1998) Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36(4):859–866

Pattillo ME (1998) Sweet mothers and gangbangers: Managing crime in a black middle-class neighborhood. Soc Forces 76(3):747–774

Paxton P, Hipp JR, Marquart-Pyatt S (2011) Nonrecursive models: endogeneity, reciprocal relationships, and feedback loops, quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage, Los Angeles

Perrin A, Gillis A (2019) How college makes citizens: higher education experiences and political engagement. Socius 5:1–16

Peterson RD, Krivo LJ (2010) Divergent social worlds: neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. Russell Sage, New York

Pfeffer FT (2018) Growing wealth gaps in education. Demography. In Press, New York

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster, New York

Raftery AE (1995) Bayesian model selection in social research. In: Sociological methodology 1995, Vol 25

Reardon SF (2011) The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: new evidence and possible explanations. Whither opportunity 91–116

Reardon SF (2016) School segregation and racial academic achievement gaps. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 2 (5):34–57

Sampson RJ (1993) Linking time and place: dynamic contextualism and the future of criminological inquiry. J Res Crime Delinq 30(4):426–444

Sampson RJ (2002) Transcending tradition: new directions in community research. Chicago Style Criminol 40(2):213–230

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago, Chicago

Sampson RJ, Byron Groves W (1989) Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Sociol 94(4):774–802

Sánchez-Jankowski M (2008) Cracks in the pavement: social change and resilience in poor neighborhoods. University of California Press, California

Schuerman L, Kobrin S (1986) Community careers in crime. Crime Justice 8:67–100

Sharkey P (2013) Stuck in place: urban neighborhoods and the end of progress toward racial equality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Slater T (2013) your life chances affect where you live: a critique of the ‘cottage industry’ of neighbourhood effects research. Int J Urban Reg Res 37(2):367–387

Small ML, Manduca RA, Johnston WR (2018) Ethnography, neighborhood effects, and the rising heterogeneity of poor neighborhoods across cities. City Community 17(3):565–589

Smith EJ, Marcum CS, Boessen A, Almquist ZW, Hipp JR, Nagle NN, Butts CT (2015) The relationship of age to personal network size, relational multiplexity, and proximity to alters in the western United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 70(1):91–99

Spiro ES, Almquist ZW, Butts CT (2016) The Persistence of division geography, institutions, and online friendship ties. Socius Sociol Res Dyn World 2:1–15

Stewart R, Uggen C (2020) Criminal records and college admissions: a modified experimental audit. Criminology 58(1):156–188

Stock JH, Watson MW (2007) Introduction to econometrics. Addison Wesley, Boston

Stuart BA, Taylor EJ (2021) The effect of social connectedness on crime: evidence from the great migration. Rev Econ Stat 103(1):18–33

Stults BJ (2010) Determinants of Chicago neighborhood homicide trajectories: 1965–1995. Homicide Stud 14(3):244–267

Swaroop S, Morenoff JD (2006) Building community: the neighborhood context of social organization. Soc Forces 84(3):1665–1695

Sweeten G (2006) Who will graduate? Disruption of high school education by arrest and court involvement. Justice Q 23(4):462–480

Taub RP, Surgeon GP, Lindholm S, Otti PB, Bridges A (1977) Urban voluntary associations, locality based and externally induced. Am J Sociol 83(2):425–442

Taylor RB (2015) Community criminology: fundamentals of spatial and temporal scaling, ecological indicators, and selectivity bias. NYU Press, New York

Tighe JR, Ganning JP (2015) The divergent city: unequal and uneven development in St. Louis. Urban Geogr 36(5):654–673

Torche F (2011) Is a college degree still the great equalizer? Intergenerational mobility across levels of schooling in the United States. Am J Sociol 117(3):763–807

Van Tran, C, Graif C, Jones AD, Small ML, Winship C (2013) Participation in context: neighborhood diversity and organizational involvement in Boston. City Community 12(3):187–210

Velez MB (2001) The role of public social control in urban neighborhoods: a multilevel analysis of victimization risk. Criminology 39(4):837–863

Velez MB, Krivo LJ, Peterson RD (2003) Structural inequality and homicide: an assessment of the black-white gap in killings. Criminology 41:645–672

Webber HS, Swanstrom T (2014) Rebound neighborhoods in older industrial cities: the story of St. Louis. Public Policy Research Center, St. Louis

Weisburd D (2015) The law of crime concentration and the criminology of place. Criminology 53(2):133–157

Weisburd D, Bushway S, Lum C, Yang S-M (2004) Trajectories of crime at places: a longitudinal study of street segments in the City of Seattle. Criminology 42(2):283–321

Weitzman A (2018) Does increasing women’s education reduce their risk of intimate partner violence? Evidence from an education policy reform. Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12181

Wenger MR (2019) Omitted level bias in multilevel research: an empirical test distinguishing block-group, tract, and city effects of disadvantage on crime. Justice Q. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1649449

Western B, Kleykamp M, Rosenfeld J (2006) Did falling wages and employment increase U.S. imprisonment? Soc Forces 84(4):2291–2311

Whyte WF (1943) Street corner society: the social structure of an Italian Slum. University of Chicago, Chicago, p 1943

Wickes R, Hipp J, Sargeant E, Mazerolle L (2017) Neighborhood social ties and shared expectations for informal social control: Do they influence informal social control actions? J Quant Criminol 33(1):101–129

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Download references

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was obtained from the University of Missouri St. Louis through the School of Public Policy’s Creating Whole Communities Fellowship and though the College of Arts and Sciences Research Grant Program. We also thank Lee Slocum for insightful comments on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri – St. Louis, 531 Lucas Hall, One University Blvd., St. Louis, MO, 63121, USA

Adam Boessen, Marisa Omori & Claire Greene

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Adam Boessen .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The figure 3 (A) and (B) have been corrected.

See Tables 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , and 13 . See Figs. 7 , 8 , and 9 .

Violent crime rate by region and racial composition over time

Figures %bachelor’s degrees on violent crime by racial composition 1970–2010

Figures %high school degrees only on violent crime by racial composition 1970–2010

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Boessen, A., Omori, M. & Greene, C. Long-Term Dynamics of Neighborhoods and Crime: The Role of Education Over 40 Years. J Quant Criminol 39 , 187–249 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09528-3

Download citation

Accepted : 20 August 2021

Published : 01 October 2021

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09528-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Communities and crime

- Longitudinal

- neighborhood studies

- Educational attainment

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Criminal Justice

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Education and crime.

Although the topic of education and crime may seem straightforward, there are many different viewpoints from which it can be examined. Researchers have studied this topic from many different perspectives. As a result of this research, several connections between education and crime have been introduced into the literature and are widely accepted. (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

I. Introduction

Ii. general perspectives on education and crime, iii. definitions, iv. education’s impact on crime, v. crime’s impact on education.

VI. Conclusion and Bibliography

The purpose of this research paper is to provide an overview of the topic of education and crime. Although at first glance this appears to be a simple task, there is an inherent complexity to examining such a broad subject. There are many different perspectives from which a discussion of education and crime could develop. Criminologists might assume that a discussion of education and crime would comprise an overview of the impact that an individual’s education level may have on his or her criminal or antisocial behavior. Alternatively, parents might assume it is a discussion of the impact of school violence and crime on the safety and learning of their children, and legislatures might assume it to be a comparison of the monies spent on fighting crime in the United States versus those spent to improve American schools. A novice might be expecting all or none of these approaches. This research paper attempts to address all of these views, albeit briefly.

The research paper begins with an overview of the generally accepted views about the relationships between education and crime. Given the volume of research on this topic, researchers have generally agreed on several basic specifics that they believe reflect the true relationship between crime and education. Next, this research paper attempts to clarify several points that need to be addressed initially. First, several general terms are defined (e.g., education, educational attainment, intelligence, street smarts, and crime) and then discussed as they are used in the study of the connections between education and crime. Finally, a discussion of how these terms intermingle is offered.

In order to develop a comprehensive framework from which to examine the concept of education and crime, two overall perspectives are addressed: (1) education’s impact on crime and (2) crime’s impact on education. It is hoped that through a discussion of these two general perspectives readers can develop an appreciation for the complexity of such a broad research area.

The concept of education’s impact on crime is examined first. In this examination, education is in essence discussed as a definite inverse correlate between its attainment and criminal behavior; that is, as one (education) increases, the other (crime) decreases. A discussion of education’s preventative nature is also presented, with a focus on its repressive nature in regard to initial criminal behavior and eventual recidivism rates. This examination involves a brief discussion of the connection between intelligence (IQ) and crime.

Crime’s impact on education is also discussed as the second overall perspective in examining education and crime. In this discussion, crime is identified as a potential barrier to educational opportunity and attainment. Strong evidence supports the belief that criminal behavior and crime often block many people from beginning the educational process. That many others are prevented from educational attainment due to arrests, periods of incarceration, and past convictions/criminal histories also has strong empirical support. Finally, violence and safety issues in schools are briefly discussed in regard to the way they influence these subjects.

Although the topic of education and crime may seem straightforward, there are many different viewpoints from which it can be examined. Researchers have studied this topic from many different perspectives. As a result of this research, several connections between education and crime have been introduced into the literature and are widely accepted. The following are a few of the empirically supported beliefs about the connections between education and crime:

- A person’s lack of education often increases the likelihood that he or she will become involved in crime and antisocial behavior. The opposite is considered true as well: The more education an individual has, the increased likelihood that he or she will live a crime-free life.

- The lack of educational attainment generally decreases one’s future employment opportunities because of increasing hiring standards in society, thus leading to possible criminal behavior for those individuals who cannot obtain viable employment.

- The lack of education and educational attainment generally limits one’s IQ, thus making him or her more vulnerable to others for exploitation and potential secondary criminal involvement.

- The more educated a community is, the less crime it experiences.

- The more educated a person is, the less he or she fears crime, and the less it significantly affects his or her life.

- It is generally believed that increases in one’s criminal behavior decrease his or her ability (and motivation) to complete higher levels of education (i.e., dropping out of school, getting expelled).

- History has demonstrated that increases in crime rates will almost always drain valuable resources from a community’s educational needs and require that those resources be directed toward crime control efforts.

- History has also shown that an increase in local neighborhood crime very often decreases the effectiveness of local schools’ educational programs and even student attendance.

- African Americans and Hispanics, overall, have less educational attainment than other racial groups. They also have a higher dropout rate than other racial groups. African Americans and Hispanics who drop out of school have a much higher rate of incarceration than those who do not. Research has empirically supported the theory that African Americans and Hispanics have higher rates of criminal behavior, and many scholars argue that there is a definite correlation between race and crime.

- On a practical level, one need only look at the fact that on days when school is in session, the level of property crime committed by juveniles decreases drastically.

Given these findings, it is difficult for many people to believe that, given that the United States has one of the highest incarceration rates in the industrialized world, its rate of spending on educational systems is among the lowest. Many consider this to be one of the major catalysts for the ongoing increases in delinquent and violent behavior in America.

To understand the possible connections and correlations between education and crime, one must first have an understanding of the essential parts of this discussion. These essential parts are actually definitions of several basic terms that people often use without giving much thought to their proper connotation. These terms may seem universally understood, but, as with many seemingly basic concepts, they have many different interpretations. In the sections that follow, definitions are provided for several key terms: education, educational attainment, intelligence, street smarts, and crime.

A. Education

The word education encompasses both the teaching and instruction and the learning of knowledge and information. This could involve the learning of proper social conduct and/or the absorption of technical competency. Simply put, education is one’s ability to know something and his or her ability to then do something with this information. It very often focuses on the development of one’s skills to work effectively in various trades or professions. It also involves the development of one’s mental capacity, moral development, and global understanding.

Formal education consists of methodical instruction, teaching, and training by professional teachers, instructors, trainers, and professors, whereas informal education generally consists of instruction from parents, families, peers, or social interactions. The former consists of the application of pedagogy (i.e., strategies and/or styles of instruction) and the development of curricula (i.e., a set of instructional activities to offer instruction), whereas the latter consists of the social learning that a person gains from interactions with his or her intimate peer groups.

In evaluations of the topic of education and crime, education is most often viewed as something that one is given, has, or accepts, that influences his or her future behavior; that is, education is something that changes how a person views himself or herself and his or her environment. Education is generally viewed as a positive influence on one’s behavior and life. It is widely accepted that the more education a person has, the more social that person’s behavior will be, and the more opportunities he or she will have; he or she ultimately will have a better quality of life. A basic assumption in the field of criminology is that the higher a quality of life one experiences, the less likely he or she will be motivated to be involved in criminal or antisocial behavior.

B. Educational Attainment

Educational attainment is generally viewed as a measure of the amount of education a person has completed at any given point in his or her life. This usually involves a listing of the highest level of education a person has successfully completed (e.g., high school diploma, college degree). The term also can refer to any other type of technical learning that one may have, such as a technical certification or professional license.

In discussions of education and crime, educational attainment often is seen as an accomplishment that is believed to have a positive immediate or long-term impact on a person’s prosocial behavior and success in life. The general view is that higher levels of educational attainment allow people more options for higher levels of employment. In turn, higher levels of employment generally lead to more income. The logic in this line of thinking is that the more income one has, the less likely he or she will be to seek criminal behavior or be interested in antisocial behavior.

C. Intelligence

Intelligence (also often referred to as intellect) is an all encompassing term used to describe the capacity of one’s mind and its associated abilities, including such human capabilities as the ability to reason, to plan, to solve problems, to think abstractly, to comprehend ideas, to use language, and to learn.

There are, of course, many ways to define intelligence. This is especially true when one is applying this trait to animal behavior, or even to plants. Some scholars argue that the concept of intelligence also includes such traits as creativity, personality, character, knowledge, and/or wisdom. Some have also argued that traditional measures of intelligence such as IQ tests, for example, are inadequate, because people can demonstrate intelligence in many ways. Some arguments claim that people can demonstrate their intelligence in eight different ways: (1) linguistic intelligence (“word smart”), (2) logical–mathematical intelligence (“number/reasoning smart”), (3) spatial intelligence (“picture smart”), (4) bodily– kinesthetic intelligence (“body smart”), (5) musical intelligence (“music smart”), (6) interpersonal intelligence (“people smart”), (7) intrapersonal intelligence (“self smart”), and (8) naturalist intelligence (“nature smart”).

In examinations of education and crime, intelligence often takes on several interesting perspectives. Some people argue that extremely high and extremely low levels of intelligence often lead to criminal and antisocial behavior. Individuals with very high levels of intelligence can use their intellect to mastermind large criminal efforts, and those with very low levels of intelligence are victimized and often the pawns of these more highly educated individuals. Higher levels of intellect are often found in people who are involved in organized and white-collar crime (e.g., embezzlement), whereas lower levels of intellect are often found in disorganized and blue-collar crime (e.g., street crime).

D. Street Smarts

Although street smarts is not a very technical or academic term (some people consider it to be a slang term), many use it to describe the unique abilities possessed by many individuals. It often is used to describe a person who does not have much formal education (i.e., educational attainment), or a great deal of mental capacity or ability (i.e., intelligence), but who has a great or cunning ability to survive in almost any environment (especially in dangerous ones). The skills and abilities often demonstrated by people who have street smarts are things such as a unique ability to read others’ body language and behavior. Such individuals also have the ability to understand the complexities of human behavior, drives, and motivations.Very often, these abilities are developed by people who need to survive in impoverished and dangerous neighborhoods that provide very little assistance or support to their inhabitants. Some people also call these skills common sense, that is, the ability to figure out what works and what does not work in any given situation without any formal instruction or study.

In examinations of education and crime, street smarts often are viewed as behaviors or abilities that lead a person toward criminal or antisocial behavior. Much of this view originates from the belief that most crime is street-level, or blue-collar crime; thus, it is activity most often engaged in by people living on the street who are either unemployed or employed in blue-collar positions. Many people would argue that common sense is something possessed by most law-abiding citizens but that street smarts are possessed only by the so-called criminal element.

Crime is most often defined as any breach of an established rule, regulation, or law committed by someone for whom a punishment may ultimately be prescribed by some governing authority or law enforcement body. Crime is also often defined as any deviant behavior that violates prevailing norms, specifically, cultural standards prescribing how humans ought to behave normally.

Academics often approach this topic through efforts to identify the complex realities surrounding the concept of crime. They seek to understand how changing social, political, psychological, and economic conditions may affect the current definitions of crime. Criminologists understand that this will affect the form of the legal, law enforcement, and penal responses made by any given state.

There are many different ways to classify crimes. A very basic method is to separate them into two types: (1) mala prohibita and (2) mala in se. Mala prohibita (“evil prohibited”) crimes are those that are illegal because legislatures label and identify them as such. These are crimes such as seat belt laws, helmet laws, or gambling laws. The other type of crime is labeled mala in se (“evil in itself ”). These acts, such as murder and sexual assault, are almost universally deemed harmful and negative.

In examinations of education and crime, crime often is viewed as acts committed by people who lack education; lack any educational attainment; and, most often, lack any higher level of intelligence. However, crime is a much more complex human experience and behavior than this view represents.

The topic of education and crime can be approached from many different perspectives, so a framework for a basic understanding must be developed. The first area of discussion is education’s impact on crime and criminal behavior. Although this issue is debatable, there is an overwhelming consensus among public officials, academics, teachers, and parents that postsecondary education is one of the most successful and cost-effective methods of preventing crime. Much of this consensus has been derived from the volumes of empirical research that has examined educational attainment as it relates to crime trends and public safety. Comparisons of state-level education data and crime and incarceration rates have consistently supported the fact that states that have focused the most on education (in general, financial support) tend to have lower rates of violent crime and incarceration. Although education can never be viewed as a “cure all” or magic bullet that will guarantee reductions in criminal activity or crime rates, research suggests that increased investments in quality education can have a positive public safety benefit.

A. Education as Crime Prevention

One of the most dominant ideas under the umbrella concept of education’s impact on crime is the belief that a reduction in crime can most often be achieved by increased crime prevention and that the most effective form of crime prevention is achieved through education. Most people would argue that education can be an important element in preventing individuals from engaging in criminal behavior. Given the previous discussions in this research paper, increased levels of education generally lead to many other characteristics that are viewed as positive correlates of lessening one’s criminal or antisocial behavior.

The literature generally offers two explanations for the preventive force of education on crime and antisocial behavior. The first is that education may change individuals’ preferences (and, in turn, their breadth of choices). The second explanation is that education contributes to a lower time preference (i.e., learning the consequences of one’s actions often make that individual postpone the direct satisfaction of needs). Some scholars argue that education leads to a lower time preference for consumption in the present (teaching one the potential negative aspects of immediate gratification) and a higher time preference for consumption in the future (teaching one the benefits of working in the present to prepare for the future).

Many researchers argue that formal education (i.e., educational attainment) has a very strong impact on teaching students (through the study of history, sociology, and other subjects) on which they should focus more of their attention in the future. Formal schooling and instruction can communicate images of the situations and difficulties of adult life, which are inevitable future issues for all adolescents. Thus, educated people should be more productive at reducing the remoteness of future pleasures.

Many researchers also argue that the more education an individual has, the more heavily he or she will weigh the future consequences (i.e., punishment) of his or her current criminal or antisocial actions. If more education leads individuals to understand the benefit of delayed gratification, then people with a higher education should be deterred from committing criminal acts. It is believed that higher levels of education will make the immediate gratification of an individual’s preferences and desires through criminal activities less important.

Most empirical studies have addressed the relationship between education and crime. Some have found that adolescents who are involved in paid employment or attend K–12 education are less likely to engage in criminal behavior. This suggests that a reduction in criminal behavior contributes largely to the social rate of return for the monies spent on education in the United States. There is much debate on the correlation between the money spent on education and the quality of education and its resultant overall impact on criminal behavior.

Not all studies find that more highly educated people are less likely to engage in criminal behavior, however. Some researchers argue that a country’s average education level does not necessarily have a statistically significant effect on the number of violent crimes (e.g., homicides and robberies). As discussed earlier, many have also argued that increased levels of education actually facilitate the criminal behavior in some individuals because of their increased abilities and knowledge (e.g., computer fraud, pyramid schemes).

The following is a list of empirically supported findings about the connections between crime prevention and education:

- Most studies have found that graduation rates are generally associated with positive public safety outcomes and lower crime rates for communities.

- States with higher levels of educational attainment also have crime rates lower than the national average.

- States with higher college enrollment rates experience lower violent crime rates than states with lower college enrollment rates.

- States that make more significant monetary investments in higher education experience more positive public safety outcomes and lower crime rates.

- The risk of incarceration, higher violent crime rates, and low educational attainment are concentrated among communities of color, whose members are more likely to suffer from barriers to educational opportunities.

- Disparities in educational opportunities contribute to a situation in which communities of color experience less educational attainment than whites, are more likely to be incarcerated, and are more likely to face higher violent crime rates.

For most people, the connection between education and crime prevention is easy to see. Criminologists have spent centuries trying to determine the causes of criminal and antisocial behavior. A central component that emerges over and over is the idea of individual motivation and desire. Human motivation and desire are very complex natural occurrences, and they are difficult to understand, although most people would argue that it is easy to understand the connection between these traits and criminal behavior.

B. The Connection Between Intelligence (IQ) and Crime

Many trends have been supported by contemporary research that has examined possible connections between education and criminal behavior. That levels of education (higher and lower) are significant in the manifestation of criminal behavior has received empirical support, as has the notion that individuals with learning disabilities (and thus with lower education, intelligence, and coping skills) are more prone to violent behavior.

The major reason for these connections is the interrelated causal pattern of events that occur in learning, with education at the center. School achievement is generally predictive of prosocial behavior, designated as upholding the moral values of a society. Most people would argue that school achievement predicts prosocial behavior because in most societies academic achievement is interrelated with several other variables, such as financial success, high self-esteem, and an internal locus of control. This particular model may account for the reasoning behind the general idea that individuals with a high IQ generally have fewer tendencies for criminal behavior than individuals with a low IQ.

Investigations of the connection between criminal behavior and IQ often are based on the general hypothesis that having a higher IQ results in easier achievement in school. As stated earlier, doing well academically is associated with several societal factors as well. Individuals with a lower IQ may not succeed as much academically, which would result in lower self-esteem and not as much financial success, resulting in an increased disposition toward criminal behavior. This would seem to highlight the importance of stressing education and addressing issues of learning disabilities at an early age to prevent, or at least mitigate, these negative attributes, thus preventing future criminal behavior and the resulting increased crime rates.

The connection between one’s intelligence level and his or her criminal behavior is a very complicated and controversial area. Empirical research most often finds that IQ and crime are actually negatively correlated; that is, as one increases, the other decreases. Explanations for this generally fall into three approaches: (1) IQ and crime are spuriously, not causally, correlated; (2) low IQ increases criminal behavior; and (3) criminal behavior actually decreases IQ.

There are also popular arguments against IQ as a cause of crime. Some scholars argue that standardized IQ tests measure only middle-class knowledge and values instead of innate human intelligence. As a result, the fact that most minority groups and impoverished populations score lower on IQ tests simply reflects their diverse cultural backgrounds. These same groups also commit proportionately more crime because they suffer structural disadvantages, such as poverty and discrimination. Consequently, the same people who score low on IQ tests also tend to commit more crime, and so IQ and crime are empirically correlated. Thus, this correlation is not causal but reflects only culturally biased testing of intelligence (see Gardner, 1993).

A variation of this argument holds that the structural disadvantages that increase crime rates also reduce educational opportunities, thus lessening individuals’ ability and motivation to score well on IQ tests. Many researchers argue that the IQ–crime correlation occurs only because both are rooted in structural disadvantage, which, in statistical terms, represents a spurious correlation at best. Although these discrimination-type hypotheses have wide appeal, they have received fairly little support in empirical studies, because IQ and crime are significantly correlated within race and class groups as well as when one statistically controls for race, class, test-taking ability, and test-taking motivation.

Another argument against IQ as a cause of crime holds that schoolteachers and administrators treat students differently according to their perceptions of the students’ intelligence, thus giving negative labels and fewer educational opportunities to those whom they see as less intelligent. These labels and constrained opportunities in turn produce feelings of alienation and resentment that lead students toward delinquent peers and criminal behavior. As such, society’s reaction to intelligence, and not any property of intelligence itself, increases criminal behavior. Unfortunately, few studies have adequately tested this labeling-type hypothesis (i.e., that deviance is derived from the labeling and mistreatment of certain individuals).

C. Education and Recidivism

Given the various aspects of this discussion, many people argue that the U.S. government should resume its long-standing policy of releasing a portion of Pell Grants (student educational grants) and other types of financial aid to qualified incarcerated individuals. They argue that the benefits of such a practice (reductions in recidivism rates) will always far outweigh the public protests against such efforts (arguing that this reduces the funds available to nonincarcerated individuals).

The focus of the pro-grant arguments is that resuming this policy would drastically decrease rates of recidivism and save individual states millions of dollars each year. Again, there seems to be overwhelming consensus among many people that postsecondary education is the most successful and cost-effective method of preventing crime. However, this often becomes controversial when one starts applying these ideas to people who have already committed criminal acts. More than 1.5 million individuals are housed in adult correctional facilities in the United States. The U.S. Department of Justice generally portrays offenders as impoverished and uneducated prior to incarceration. Inside American prisons, many adult inmates are illiterate, and many more are functionally illiterate.

Most researchers would argue that social, psychological, and demographic factors correlate strongly with recidivism. Most persons are released from prison into communities unskilled, undereducated, and highly likely to become reinvolved in crime. Rates of recidivism in the United States are extraordinarily high. Although prison-based education has been found to be the single most effective tool for lowering recidivism, today these programs are almost nonexistent. Many would also argue that prison education is far more effective at reducing recidivism than are boot camps, shock incarceration, or vocational training.

In response to the American public’s growing fear of crime and the call for more punitive measures to combat such fear, many legislators and policymakers have promoted building more prisons, enacting harsher sentencing legislation, and eliminating various programs inside prisons and jails. With rearrest rates increasing almost daily, it is clear that incarceration alone is not working in the United States. In fact, the “get tough” philosophy (originating in the mid-1980s), which pushes for more incarceration, punishment, and limitations of the activities available to prisoners, has often resulted in the elimination of strategies and programs that seek to prevent or reduce crime. As has been discussed repeatedly in this research paper, research has consistently shown that quality education is one of the most effective forms of crime prevention and that educational skills can help deter young people from committing criminal acts as well as greatly decrease the likelihood that people will return to crime after release from prison.

Despite this evidence of their extraordinary effectiveness, educational programs in correctional facilities have in many cases been completely eliminated. As of 2008, more than 1.6 million individuals were housed in adult correctional facilities in the United States, and at least 99,682 juveniles are in custody. The majority of these individuals will be released into communities unskilled, undereducated, and highly likely to become reinvolved in criminal activity. With so many ex-offenders returning to prison, it would seem clear that the punitive, incarceration-based approach to crime prevention has not worked as a basis for criminal justice policy in America. Therefore, it should not be surprising that so many people argue that the country needs to promote policies and procedures that are successful. Education, particularly at the college level, can afford individuals with the opportunities to achieve and maintain productive and crime-free lives and help to create safer communities for all.

A second overall perspective on the concept of education and crime is to examine the impact of crime on education. As with education’s impact on crime, crime’s impact on education has several directions from which it can be approached. The following sections discuss crime as a barrier to educational opportunity and attainment as well as briefly consider school safety issues.

A. Crime as a Barrier to Educational Opportunity

One of the major areas in which crime’s impact on education can be found is in how crime very often serves as a barrier to educational opportunity for many people. This barrier status can appear from two directions: (1) the negative mobility patterns for some groups in terms of traditional and nontraditional criteria for upward movement and educational achievement and (2) individuals’ lack of opportunity for educational attainment due to their own criminal behavior (e.g., incarceration, dropping out of school, and expulsions).

For many people, going to college or achieving higher levels of education is an unrealistic goal because of financial constraints or living conditions; instead, daily survival is of utmost concern. Many of these individuals have had to drop out of school at an early age to help support their families and/or take care of younger siblings; for others, their own criminal behavior became a barrier to their future educational attainment. Incarcerated individuals obviously have very few opportunities (if any) above remedial instruction that generally leads to a GED. Others, because of their behavior, have been forced out of their local schools by suspensions and/or expulsions. As state budgets become more and more restrictive, educational programs in general have been eliminated or greatly decreased.

B. Crime’s Connection to High School Graduation

As stated previously, many individuals are forced to drop out of traditional K–12 educational programs because of their own criminal or delinquent behavior. These individuals usually start off with in-school suspensions, which evolve into out-of-school suspensions and, ultimately, to expulsions. In most states where the compulsory education age is 16, these individuals often find themselves forced to attend alternative educational programs. Research has supported the belief that the majority of these youth do not seek any postsecondary educational opportunities; many do not finish high school or GED programs.

Most, if not all, of the typical criminal or delinquent school behaviors, such as skipping school, drug use, violent behavior, and engaging in property crime, correlate strongly with a lack of high school graduation. Many educational systems across the United States have adopted a zero-tolerance policy stance when it comes to any type of negative student behavior. The primary result of these policies is expulsion from school of the delinquent child, and the primary result of most expulsions is that the individual never returns to school. Thus, lacking the proper educational attainment (and, possibly, intellect), he or she is not able to be competitive in most job markets. As stated earlier, a lack of employment is a major factor in an individual’s decision to turn to criminal behavior to meet his or her financial needs.

C. School Safety Issues

A final area of discussion is the very practical impact that crime can have on education. The scope of this research paper does not allow a full examination of the issues related to school violence and its results, but it would be improper not to mention this issue at least briefly. Readers would be well advised to seek further information about the various impacts of school violence on students and teachers. There are volumes of research dealing with the most common forms of school violence: sexual harassment and bullying. These two issues alone, many people would argue, are responsible for a great deal of high school dropouts, assaults, and even school shootings.

School safety and the proper protection of students are very strongly connected to crime. The more crime a school has, the less safe the students are going to feel, and the less secure they feel, the less they will learn. When students have to worry about their safety on a daily basis at a school, the academic experiences very often get left behind. Most people would agree that learning becomes secondary very quickly when a child has to worry more about death then failure in the classroom.

Many of the connections that crime has with K–12 education relate to incidents that occur between students. There is a significant problem with bullying and sexual harassment on the campuses of many American schools. These acts, although not obviously violent, many times go unnoticed and can have an extremely negative impact on the victims. As previously stated, such treatment has been connected to high dropout rates, failing grades, and even juvenile suicides.

VI. Conclusion