You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

- Buy Tickets

- Join & Give

The Stolen Generation

Michael o’loughlin is a gamilaraay man from moree in northern nsw. he has cultural connections to ngiyampaa and worimi countries..

- Author(s) Michael O’Loughlin

- Updated 22/06/20

- Read time 5 minutes

- Share this page:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Linkedin

- Share via Email

- Print this page

On this page... Toggle Table of Contents Nav

The phrase Stolen Generation refers to the countless number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families under government policy and direction. This was active policy during the period from the 1910s into the 1970s, and arguably still continues today under the banner of child protection. It is estimated that during the active period of the policy, between 1 in 10 and 1 in 3 Indigenous children were removed from their families and communities.

The removal of Indigenous children was rationalised by various governments by claiming that it was for their protection and would save them from a life of neglect. A further justification used by the government of the day was that it was believed that “Pure Blood” Aboriginal people would die out and that the “Mixed Blood” children would be able to assimilate into society much easier, this being based on the premise that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were racially inferior to people with Caucasian background.

There were a number of government policies and legislation that allowed for the removal of Aboriginal children. One of the earliest pieces of legislation in relation to the Stolen Generation was the Victorian Aboriginal Protection Act 1869 , this legislation allowed the removal of Aboriginal people of mixed descent from Aboriginal Stations or Reserves to force them to assimilate into White Society. In NSW, the Board for the Protection of Aborigines was established in 1883, and this board was initially established to provide ‘the duty of the State to assist in any effort which is being made for the elevation of the race, by affording rudimentary instruction, and by aiding in the cost of maintenance or clothing where necessary, as well as by the grant of land, gifts of boats, or implements of industrial work.’ [1] Prior to 1909, this Board acted without legislative authority. In 1915, the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915 (NSW) was introduced, this Act gave the Aborigines’ Protection Board the authority to remove Aboriginal children without having to establish in court that the children were subject to neglect.

Once a child was removed from their family, they were forced to assimilate into the White Society. This included being forbidden to speak their traditional language or participate in any form of cultural practice or activity, and having to adopt new names and identities. Many of these children were informed that their families had either given them up or had died. To increase the success of removal policies, the authorities would often send the children vast distances from their Countries and families. For some of the children that were removed and forced to assimilate into White Society, they developed a shame of their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander heritage. For some as they grew older and started their own families, they continued to hide their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander heritage from their family, with many not accepting this heritage until much later in life.

Many of the stolen children were placed into group homes such as the Kinchela Boys Home and the Cootamundra Girls Training Home. At these homes the children were taught skills such as housekeeping and farm handing, so that once they were to leave the home, they would be able to be placed into the service of a White family. Whilst in these training homes many of the children experienced neglect and abuse in many forms, including sexual and physical abuse.

In 1969, New South Wales abolished the Aborigines Welfare Board, and this effectively resulted in all States and Territories having repealed legislation that allowed for the removal of Aboriginal children under a policy of ‘protection’.

The practice of removing children continues to this day, research released in 2019 compiled from data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and data from the Western Australia Department of Communities and Department of Health indicate that between 2012 and 2017 the number of Aboriginal Children placed into Out of Home Care rose from 46.6 per 1000 to 56.6 per 1000 children. This research also found that the rate of infants (under 1 year old) placed in to Out of Home Care rose from 24.8 to 29.1 per 1000, between 2013 and 2016 [2].

On the 13th February 2008, Kevin Rudd, the then Prime Minister of Australia, made an Apology to the members of the Stolen Generation. Although the period known as the Stolen Generation technically ended in 1969, it is important to understand that the effect of the Stolen Generation is still being felt by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples today. Many Aboriginal families have experienced inter-generational trauma, due to the trauma experienced by their parents or grandparents who lived through this period of history. The Stolen Generation has resulted in traditional knowledge being lost as this knowledge was not able to be passed down to the next generation.

[1] AIATSIS: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/catalogue_resources/91930.pdf

[2] National Indigenous Times: Rising Rate of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care: https://nit.com.au/rising-rate-of-aboriginal-children-in-out-of-home-care/

Further information

- http://www.stolengenerationstestimonies.com/

- https://healingfoundation.org.au/

- https://www.sbs.com.au/news/timeline-stolen-generations

- https://kinchelaboyshome.org.au/

- https://www.cootagirls.org.au/

- https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/bringing-them-home-report-1997

- https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/articles/apology-australias-indigenous-peoples

- https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/aborigines-protection-act

Teaching resources

- https://healingfoundation.org.au/schools/

About the author

Michael O’Loughlin is a Gamilaraay man from Moree in northern NSW. He has cultural connections to Ngiyampaa and Worimi countries. Michael is the education officer for IndigenousX, having previously worked in the government sector and the private sector in various mentoring roles, including juvenile justice and high schools.

The Australian Museum respects and acknowledges the Gadigal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Custodians of the land and waterways on which the Museum stands.

Image credit: gadigal yilimung (shield) made by Uncle Charles Chicka Madden

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

‘The Stolen Generations, a Narrative of Removal, Displacement and Recovery’.

2014, Lives in Migration: Rupture and Continuity. Australian Studies Centre UB (2011): 30-49. Barcelona, Spain. http://www.ub.edu/dpfilsa/welcome.html</a. Legal deposit B.44596-2010 (E-book).

The case of territorial dispossession affecting Indigenous Australia (Aborigines and Torres-Straight Islanders) over the last two centuries, an instance of forced migration to the margins of white settler society, may speak back to European fears of displacement by the ethnic Other. This chapter analyses the ways in which Australian settler society has dealt with the Aboriginal population in its colonising thrust, and what strategies it has employed to effect Aboriginal cultural and physical displacement from their tribal lands in its aim to control vital resources. White frontier violence, the dispossession of ancestral country, the relocation to missions and reserves, child removal and institutionalisation have all played their role in a process of displacement often considered genocidal. The Indigenous law expert Larissa Berendt observes that “the political posturing and semantic debates do nothing to dispel the feeling Indigenous people have that [genocide] is the word that adequately describes our experience as colonized people” (in Moses 2005: 17). This essay will take Berendt’s cue in focusing on the plight and testimony of the Stolen Generations, a large group of mixed-descent children forcibly removed at great distances from their Aboriginal families and raised to fit into white society. Their vicissitudes have lately become visible, worded and documented in human-right reports, academic study and artistic and literary work. It is these children that became the main focus of assimilative government action; it is in their defencelessness that the breach of basic human rights is salient; it is also in their current recovery as Indigenous rather than white Australians that the resilience and ongoing presence of the Aboriginal communities and cultures are manifest, as shown in the Bringing-Them-Home Report. After an overview of Australian assimilative policies and these children’s location in these, this chapter will address their testimony of diasporic displacement in some representative Indigenous literary output from the state of Western Australia.

Related Papers

Cornelis Martin Renes

It is nowadays evident that the West's civilising and eugenic zeal have had a devastating impact on all aspects of the Indigenous-Australian community tissue, not least the lasting trauma of the Stolen Generations. The latter was the result of the institutionalisation, adoption, fostering, virtual slavery and sexual abuse of thousands of mixed-descent children, who were separated at great physical and emotional distances from their Indigenous kin, often never to see them again. The object of State and Federal policies of removal and mainstream assimilation between 1930 and 1970, these lost children only saw their plight officially recognised in 1997, when the Bringing Them Home report was published by the Federal government. The victims of forced separation and migration, they have suffered serious trans-generational problems of adaptation and alienation in Australian society, which have been not only documented in the aforementioned report but also in Indigenous-Australian literature over the last three decades. The particular imprint of the Stolen Generations on the life and oeuvre of the Nyoongar author Kim Scott shows how a liminal, hybrid identity can be firmly in place yet. Un-writing past policies of physical and 'epistemic' violence on the Indigenous Australian population, his fiction addresses a way of approaching transculturality within the Australian nation-space from an inclusionary Indigenous perspective.

Coolabah 10 (2013): 177-189. Spain http://www.ub.edu/dpfilsa/CoolabahMainpage.html. ISSN 1988-5946.

It is nowadays evident that the West’s civilising, eugenic zeal have had a devastating impact on all aspects of the Indigenous-Australian community tissue, not least the lasting trauma of the Stolen Generations. The latter was the result of the institutionalisation, adoption, fostering, virtual slavery and sexual abuse of thousands of mixed-descent children, who were separated at great physical and emotional distances from their Indigenous kin, often never to see them again. The object of State and Federal policies of removal and mainstream absorption and assimilation between 1930 and 1970, these lost children only saw their plight officially recognised in 1997, when the Bringing Them Home report was published by the Federal government. The victims of forced separation and migration, they have suffered serious trans-generational problems of adaptation and alienation in Australian society, which have been not only documented from the outside in the aforementioned report but also given shape from the inside of and to Indigenous-Australian literature over the last three decades. The following addresses four Indigenous Western-Australian writers within the context of the Stolen Generations, and deals particularly with the semi-biographical fiction by the Nyoongar author Kim Scott, which shows how a very liminal hybrid identity can be firmly written in place yet. Un-writing past policies of physical and ‘epistemic’ violence on the Indigenous Australian population, his fiction addresses a way of approaching Australianness from an Indigenous perspective as inclusive, embracing transculturality within the nation-space. Key words: Stolen Generations; absorption; assimilation; eugenics; Indigenous literature; life-writing; Kim Scott; trauma; displacement; identity formation.

Robert van Krieken

From around the turn of 20th century up to the 1970s, Australian government authorities assumed legal guardianship of all Indigenous children and removed large numbers of them from their families in order to `assimilate' them into European society and culture. This policy has been described as `cultural genocide', even though at the time it was presented by state and church authorities as being `in the best interests' of Aboriginal children. This article outlines the results of a study of the development of the policy of forced child removal, its antecedents, its surrounding philosophy and politics and the emergence of a more critical understanding of it in recent years, as well as examining the more general implications of this history for the sociology of childhood.

“Australia’s Darkest Dreams: Persecution and Flight in Aboriginal and Refugee Life Writing,” in: Beyond ‘Other’ Cultures: Transcultural Perspectives on Teaching the New Literatures in English. Sabine Doff und Frank Schulze-Engler (eds.). Trier: WVT, 2011: 143-155.

Sissy Helff

Devi Kamala

Australian Journal of Social Issues

terri libesman

SHS Web of Conferences

Nuriyeni Bintarsari

This paper will discuss the Forced Removal Policy of Aborigine children in Australia from 1912 to 1962. The Forced Removal Policy is a Government sponsored policy to forcibly removed Aborigine children from their parent’s homes and get them educated in white people households and institutions. There was a people’s movement in Sydney, Australia, and London, Englandin 1998to bring about “Sorry Books.” Australia’s “Sorry Books” was a movement initiated by the advocacy organization Australian for Native Title (ANT) to address the failure of The Australian government in making proper apologies toward the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. The objective of this paper is to examine the extent of cultural genocide imposed by the Australian government towards its Aborigine population in the past and its modern-day implication. This paper is the result of qualitative research using literature reviews of relevant materials. The effect of the study is in highlighting mainly two t...

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy

Joanne Faulkner

Drawing on Alexis Wright’s novel The Swan Book and Irene Watson’s expansive critique of Australian law, this article locates within the settler–Australian imaginary the figure of the ‘wounded Aboriginal child’ as a site of contest between two rival sovereign logics: First Nations sovereignty (grounded in a spiritual connection to the land over tens of millennia) and settler sovereignty (imposed on Indigenous peoples by physical, legal and existential violence for 230 years). Through the conceptual landscape afforded by these writers, the article explores how the arenas of juvenile justice and child protection stage an occlusion of First Nations sovereignty, as a disappearing of the ‘Aboriginality’ of Aboriginal children under Australian settler law. Giorgio Agamben’s concept of potentiality is also drawn on to analyse this sovereign difference through the figures of Terra Nullius and ‘the child’.

Humanities 4.4 (2015): 661-675

Justine Seran

Arena journal

Thalia Anthony

In the Northern Territory (NT), all children in youth detention are Aboriginal and their numbers have been steadily growing over the past decade. This article examines the transcripts of the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory (2016-17) (hereafter the Royal Commission) to uncover processes and discourses of exclusion of Aboriginal children who have been rendered by the state surplus to humanity. It draws attention to the state's practices in youth detention and the justifications of guards and detention managers before the Royal Commission as premised on notions of Aboriginal children's disorder and deviance. This characterisation, and the ensuing harmful state practices, have taken on a new intensity since the federal govern ment introduced racially discriminatory policies and practices in 2007 in order to restrict the rights of Aboriginal people living in remote NT communities and town camps.

RELATED PAPERS

Muhammad Qusairi

Pradumn Pandey

Mohammad Affan Fajar Falah

Victor Eijkhout

Claudia Paez

ACM SIGGRAPH 2006 Sketches on - SIGGRAPH '06

Shahzad Malik

Traffic Injury Prevention

Ashley Rosenberg

Transplantation

Rakib Hasan

Journal of Geophysical Research

Bisher Imam

Revista Latino-americana de Geografia e Genero

Beatriz Nader

Ecology and Society

Achim Schlüter

DIVERSITATES International Journal

Vilma Aparecida da Silva Fonseca

cristina coscia

João de Lacerda Matos

Bryan Oliveira

Klio. Czasopismo Poświęcone Dziejom Polski i Powszechnym

Magdalena Niedźwiedzka

Boris Valentin

Journal of Cluster Science

Suhas Ballal

Rosa Nina Enrich

AMV Antonio María Valencia

Natalia Puerta

Journal of Chromatographic Science

Scott Abeel

Rechtsgeschichte

Dr. Horst Pietschmann - - - - - - - - - - - Pietschmann

Journal of Wildlife Management

Chris Nicolai

Case Medical Research

Jana Sremaňáková

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

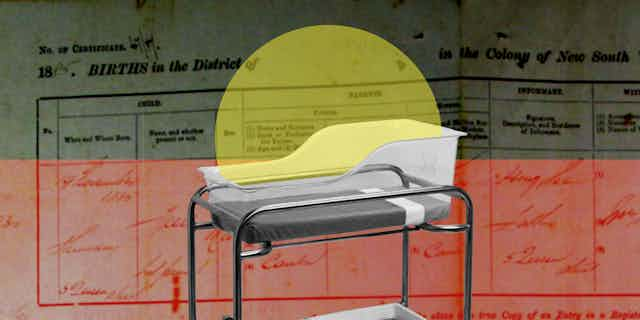

Friday essay: ‘too many Aboriginal babies’ – Australia’s secret history of Aboriginal population control in the 1960s

ARC DECRA Research Fellow, Australian National University

Director of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Research Office, University of Sydney

Faculty of Arts Indigenous Postdoctoral Fellow, Indigenous and Settler Relations Collaboration, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

University of Sydney and Australian National University provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article may contain images of deceased people. It contains mentions of the Stolen Generations, and policies using outdated and potentially offensive terminology when referring to First Nations people.

The 1967 referendum is celebrated for its promise that First Nations people of Australia would be counted. But when they were, many white experts decided the Aboriginal population was growing too fast – and took steps to stop this growth. This was eugenics in the late 20th century.

The costs were borne by Aboriginal women who faced covert government family-planning programs, designed ostensibly to promote “choice”, but ultimately to curb their fertility.

For decades, Indigenous communities have spoken of the coercive practices of officials and medical experts around birth control and sterilisation , and how they experienced them. Now historians are finding evidence of these practices in the government’s own records from as recently as the 1960s and ‘70s.

The history of birth control is not just a story of women’s emancipation. Birth control has never been just about the rights of individual women to control their fertility. It has also been a tool of “experts” and authorities as they attempt to shape the population through the so-called “right kind” of babies. The birth of children of colour, children with disability or children born into poverty has, at various times, been considered by such “experts” as a problem to be managed.

Read more: Birthing on Country services centre First Nations cultures and empower women in pregnancy and childbirth

Fighting to have and raise children

First Nations scholars such as Jackie Huggins and Aileen Moreton-Robinson have resoundingly criticised the simple story of birth control as liberation. They argue that, while white women demanded contraception and abortion, Aboriginal women have insisted on their right to have and raise their children.

Since colonisation began, Aboriginal women have fought for this right. The Aboriginal population plummeted through the 19th century, through disease and violence: it was a battle for survival.

Until the middle of the 20th century, white Australia largely presumed Aboriginal people were a “dying race” – and that all that could be done were attempts to “ smooth the dying pillow ”, through missions and other “ protectionist ” policies. Later, these morphed into attempts to assimilate those who survived into white Australia.

In the 1920s and '30s in particular, many white Australians were preoccupied with the birth of so-called “half-caste” children, fearing they might undermine the possibility of a white Australia. Eugenic policies that prohibited marriage between First Nations and non-Indigenous people attempted to prevent the birth of these children.

Most Australians are now familiar with the devastation caused by genocidal policies of child removal that resulted in the Stolen Generations . But fewer people know that eugenic practices seeking to limit Aboriginal populations continued even in the second half of the 20th century.

The growing Aboriginal population

When the 1966 census results were published in November 1967, they told a new story about the Aboriginal population: it was growing , rapidly . Further reports of population growth soon flowed in.

In August 1968, the Canberra Times reported the Aboriginal birth rate was “twice the Australian average” and the “full-blood” birth rate would soon “equal or exceed the rate of the part-Aborigines”.

University of New South Wales ethno-psychiatrist John Cawte described an Aboriginal “ population bulge in some places and an explosion in others ”. In his 1969 letter to the Courier Mail, professor of preventative medicine at the University of Queensland, John Francis, predicted an Aboriginal population of 360 million by 2200 if current birth rates continued.

Likewise, Jarvis Nye, a founder of the prestigious Brisbane Clinic , described the “alarming situation in the quality of our young Australians”. He wrote that Aboriginal people were having “much larger families than our intelligent and provident European and Asian citizens”. Nye advocated providing “instruction in contraception” and free intrauterine devices (IUDs) and sterilisation to Aboriginal people.

In 1969, alarm around the Aboriginal birth rate escalated into national politics . Douglas Everingham, Member for Capricornia (and later minister for health in the Whitlam government), agreed the “aboriginal birth rate is excessive”. He suggested free sterilisation .

These concerns focused, particularly, on Aboriginal infant mortality , frequently presumed to be caused by a high birth rate. Academics Broom and Lancaster Jones found Aboriginal infant mortality was double that of white children. In central Australia, it was “ ten times the white Australian rate ”.

Nevertheless, they also noted that the Aboriginal population continued to rise despite high infant mortality. Concerned by the overall growth in the Aboriginal population (not simply by infant mortality), Francis criticised the provision of services to Aboriginal communities that reduced infant mortality without providing parallel measures to reduce fertility.

Read more: Why is truth-telling so important? Our research shows meaningful reconciliation cannot occur without it

'Family planning’ in remote communities

In July 1968, the Northern Territory Administration’s Welfare Branch and the Health Department outlined their plans for Aboriginal women.

Pilot projects would address the supposed “special problems” of family planning education “among unsophisticated Aboriginals in remote locations”. The minister warned this would be “sensitive”. He was aware of Aboriginal communities’ claims that family planning was, as he put it, “a white plot to wipe out the Aboriginal race”.

So “family planning” projects went quietly ahead under the Department of Health and the Northern Territory administration, with pilot projects on settlements and missions.

One began at Bagot in January 1968, with initial appointments for inserting IUDs. In 1968, a family planning “pilot project” was established at Warrabri Settlement. Another was established in 1969 at Bagot Hospital. The district welfare officer reported that at Bamyili (now Burunga) “of these, only two are socio-medical cases for whom some direct persuasion was made”.

The form of this “direct persuasion” is unclear, but it indicates Aboriginal women were directly encouraged to control their fertility if they did not make the “choice” the white officials wanted for them.

As for the method of contraception, the strong preference of practitioners and bureaucrats was IUDs. An IUD was long-lasting and crucially, it did not depend on correct daily use. Staff acknowledged the logistical difficulties of IUD insertion procedures in remote locations. The health professionals’ preference for IUDs came from their assumptions about Aboriginal women’s capacity and willingness, rather than from the women’s expressed preferences.

The Director for Welfare in the Northern Territory, Harry Giese , assessed the success of the “family planning” projects by the percentage of the Aboriginal women who had adopted contraception – not by counting the proportion who had the opportunity to make an informed choice. Around 250 women out of 4,500 (5.5%) were participating in a family planning programme by 1972.

Read more: Brenda Matthews was ripped from a loving family twice. But she was born too late to be officially recognised as Stolen Generations

What kind of ‘choice’?

So, did these women have a “choice” about their fertility? The government’s records give us little information on what these women understood about the medical procedures “recommended” to them. But these “recommendations” and “encouragements” were presented to women at a time when the Director of Welfare still controlled intimate details of their daily lives.

These included where they worked, whether they could travel, who they married, where their children would be educated and – perhaps most significantly – whether they would retain custody of their children. All these decisions fell under the sweeping authority of the Director of Welfare.

Aboriginal women’s “choice” around fertility took place in a context where women did not have freedom to raise their children, where Aboriginal motherhood was routinely denigrated and where white “experts” spoke openly of “too many Aboriginal babies”.

In this context, we conclude that policies of family planning were coercive. But there is another, more hopeful, side to this story.

As this was happening, more and more Aboriginal people moved to cities and found opportunities to network, organise and become activists. Although governments turned to “family planning” services to curb the growth of the Aboriginal population, Aboriginal women found their own opportunities.

In the 1970s, Aboriginal leader Shirley Smith argued for government funding for family planning to be handled by the Aboriginal Medical Service . This funding was increasingly transferred to the Aboriginal Medical Service throughout the 1970s. First Nations leaders such as Marcia Langton worked through the Aboriginal Medical Service to restore power and dignity to Aboriginal women.

Community-controlled health services have been a way for Aboriginal women to reassert control over their health decisions – and a powerful driver of First Nations self-determination.

What about today?

But where does the right of First Nations women to mother their children stand today?

Even now, the rates of First Nations children in out-of-home care are shocking: ( 43% of children in out-of-home care are Indigenous ). We are witnessing a new “stolen generation” .

When First Nations women still make fertility decisions within a broader context of high rates of child removal and domestic abuse, we must ask what kind of “choice” is available to them.

Given the long tail of eugenic and discriminatory policies in Australia, it is all the more important that First Nations people are able to access community-controlled healthcare reflecting holistic First Nations approaches to health – especially when it comes to women’s health.

Healthcare for First Nations women, run by and for First Nations people , is the best context for women to be able to make their own fertility decisions.

Despite government efforts to slow the growth of the Indigenous population, we are seeing more people than ever identify as Indigenous – and the First Nations population is still growing. Australia is better for it.

If you or anyone you know is experiencing mental health challenges, please contact WellMob . This resource has a list of culturally safe organisations for First Nations people.

- Birth control

- Family planning

- Australian history

- Stolen Generations

- Population control

- Sterilisation

- Aboriginal women

- Friday essay

- First Nations

- 1967 referendum

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This essay plots the history of Stolen Generation narratives in Australia, from the first Australian account for children in Charlotte Barton's A Mother's Offering to Her Children to Doris ...

Stolen Generations, a large group of mixed-descent children forcibly removed at great distances from their Aboriginal families and raised to fit into white society. Their vicissitudes have lately become visible, worded and documented in human-right reports, academic study and artistic and literary work. ...

3. complete a jigsaw reading activity based on personal stories of members of the Stolen Generations. 4. read personal stories from members of the Stolen Generations to examine the impacts of being 'stolen' on the wider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community. 5. analyse the Rudd Government's 2008 Apology to the Stolen Generations.

This essay examines the acts of racial discrimination portrayed in the book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara. It takes a close look at the historical background materials Garimara used in her narration of the Stolen Generations, and her role as an advocate for healing and reconciliation amongst her people. Experimental

References. The phrase Stolen Generation refers to the countless number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families under government policy and direction. This was active policy during the period from the 1910s into the 1970s, and arguably still continues today under the banner of child ...

This essay plots the history of Stolen Generation narratives in Australia, from the first Australian account for children in Charlotte Barton's A Mother's Offering to Her Children to Doris Pilkington Garimara's Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, Philip Noyce's film Rabbit-Proof Fence, and pedagogical materials which mediate the book and ...

The Stolen Generations. The removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969. Peter Read. Sixth reprint (2007) First published in 1981 ISBN -646-46221- 1. Foreword. This is the sixth reprint of Professor Peter Read's landmark paper The Stolen Generationsfirst written in 1981. Each year thousands of Australians read Professor ...

Stolen Generation Essay You sit and remember the time. You are woken up early one morning to the sound of your family screaming. You mother comes running up to you and start smearing mud all over your body, you try to ask her what's going on, but she doesn't reply. You see your sister, she is also covered in mud and you

This essay will take Berendt's cue in focusing on the plight and testimony of the Stolen Generations, a large group of mixed-descent children forcibly removed at great distances from their Aboriginal families and raised to fit into white society. ... Transcript_Nelson.pdf New South Wales Government. (2002, September). Upper Parramatta River ...

The stolen generations: The removal of aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969 (Occasional paper 1). Sydney, Australia: Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs NSW. Google Scholar. Read P. (1983). "A rape of the soul so profound": Some reflections on the dispersal policy in NSW. Aboriginal History, 7, 23-33.

ArticlePDF Available. The `Stolen Generations' and Cultural Genocide. August 1999. Childhood 6 (3):297-311. DOI: 10.1177/0907568299006003002. Authors: Robert Van Krieken. The University of Sydney ...

commissions. In Australia, which is the focus of this essay, personal testimo ny has played a vital role in educating Australians about the history and experiences of the Stolen Generations, and has provided a basis on which to make human rights claims. Brought to international attention through

attacks upon so-called black armband history and particularly the Stolen Generations narrative.3 This assault gathered momentum during 1999 and 2000, eventually provok-ing the political commentator and historian Robert Manne to pen In denial: the Stolen Generations and the Right, an essay in which, to quote the publicists for this new venture

The Stolen Generation Essay - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site.

The term 'Stolen Generations' refers to Indigenous Australian children forcibly removed from their families and culture by Australian governments for racial reasons from the late 1800s to the 1970s.3 Although there is continuing debate about the number of Aboriginal children removed,4 there is no doubt that.

This essay will take Berendt's cue in focusing on the plight and testimony of the Stolen Generations, a large group of mixed-descent children forcibly removed at great distances from their Aboriginal families and raised to fit into white society. ... The Stolen Generations A crucial role in the mainstream management of Indigeneity has been ...

We are witnessing a new "stolen generation". When First Nations women still make fertility decisions within a broader context of high rates of child removal and domestic abuse, we must ask ...

The Stolen Generations endured abuse, racism and death. A landmark government report, aimed to examine health, cultural and socio-economic measures for 7,900 Indigenous Australian children who were under the age of 15. These children were were living in households with at least one member of the Stolen Generations.

Sample Essay Topics - 59; Part 1 Exam Questions - 59; Part 2 Exam Questions - 60; Sample Analysis of a Part 2 Question - 60. REFERENCES & FURTHER READING 63 ... The issue of the Stolen Generation (really generations) is one of the most confronting, and for a long time suppressed, issues in Australia's history. ...

The stolen generations The stolen generations were a range of brutal removals of aboriginal children from their families between the late 1800s to the mid 1900s. The core goal in these removals was known as assimilation. Assimilation was based on the belief that aboriginals were to be treated unequally compared to the white people, and that the ...

Stolen Generation Essay - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site.

1. Stolen Generation Essay Writing an essay on the topic of the Stolen Generation is undoubtedly a challenging endeavor. This subject involves a complex and sensitive historical context, revolving around the forced removal of indigenous Australian children from their families between the late 19th century and the 1970s.

The Stolen Generation Essay. Year 10 History: The Stolen Generation - Download as a PDF or view online for free

Stolen Generations testimonies offer insights into the history, effects, and legacies of colonization in Australia—a history that is currently being contested in the public domain. In this essay ...