[email protected]

- English English Spanish German French Turkish

Thesis vs. Research Paper: Know the Differences

It is not uncommon for individuals, academic and nonacademic to use “thesis” and “research paper” interchangeably. However, while the thesis vs. research paper puzzle might seem amusing to some, for graduate, postgraduate and doctoral students, knowing the differences between the two is crucial. Not only does a clear demarcation of the two terms help you acquire a precise approach toward writing each of them, but it also helps you keep in mind the subtle nuances that go into creating the two documents. This brief guide discusses the main difference between a thesis and a research paper.

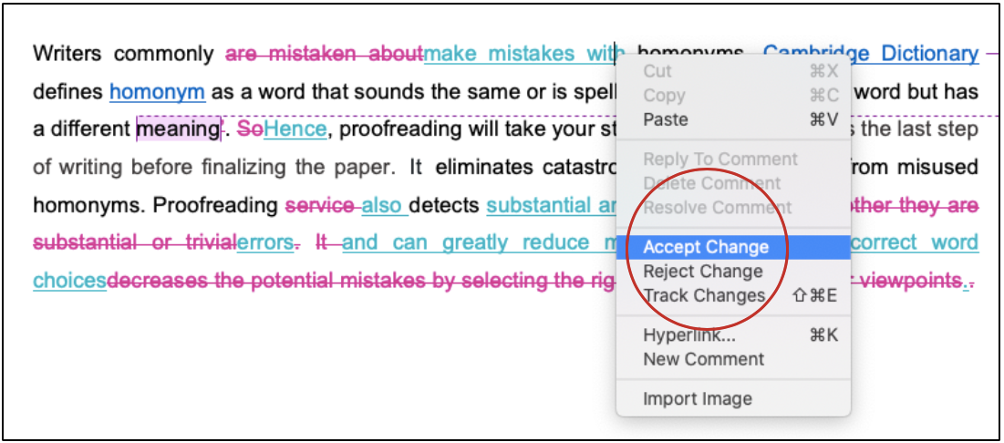

This article discusses the main difference between a thesis and a research paper. To give you an opportunity to practice proofreading, we have left a few spelling, punctuation, or grammatical errors in the text. See if you can spot them! If you spot the errors correctly, you will be entitled to a 10% discount.

It is not uncommon for individuals, academic and nonacademic to use “thesis” and “research paper” interchangeably. After all, both terms share the same domain, academic writing . Moreover, characteristics like the writing style, tone, and structure of a thesis and research paper are also homogenous to a certain degree. Hence, it is not surprising that many people mistake one for the other.

However, while the thesis vs. research paper puzzle might seem amusing to some, for graduate, postgraduate and doctoral students, knowing the differences between the two is crucial. Not only does a clear demarcation of the two terms help you acquire a precise approach toward writing each of them, but it also helps you keep in mind the subtle nuances that go into creating the two documents.

Defining the two terms: thesis vs. research paper

The first step to discerning between a thesis and research paper is to know what they signify.

Thesis: A thesis or a dissertation is an academic document that a candidate writes to acquire a university degree or similar qualification. Students typically submit a thesis at the end of their final academic term. It generally consists of putting forward an argument and backing it up with individual research and existing data.

How to Write a Perfect Ph.D. Thesis

How to Choose a Thesis or Dissertation Topic: 6 Tips

5 Common Mistakes When Writing a Thesis or Dissertation

How to Structure a Dissertation: A Brief Guide

A Step-by-Step Guide on Writing and Structuring Your Dissertation

Research Paper: A research paper is also an academic document, albeit shorter compared to a thesis. It consists of conducting independent and extensive research on a topic and compiling the data in a structured and comprehensible form. A research paper demonstrates a student's academic prowess in their field of study along with strong analytical skills.

7 Tips to Write an Effective Research Paper

7 Steps to Publishing in a Scientific Journal

Publishing Articles in Peer-Reviewed Journals: A Comprehensive Guide

10 Free Online Journal and Research Databases for Researchers

How to Formulate Research Questions

Now that we have a fundamental understanding of a thesis and a research paper, it is time to dig deeper. To the untrained eye, a research paper and a thesis might seem similar. However, there are some differences, concrete and subtle, that set the two apart.

1. Writing objectives

The objective behind writing a thesis is to obtain a master's degree or doctorate and the ilk. Hence, it needs to exemplify the scope of your knowledge in your study field. That is why choosing an intriguing thesis topic and putting forward your arguments convincingly in favor of it is crucial.

A research paper is written as a part of a course's curriculum or written for publication in a peer-review journal. Its purpose is to contribute something new to the knowledge base of its topic.

2. Structure

Although both documents share quite a few similarities in their structures, the framework of a thesis is more rigid. Also, almost every university has its proprietary guidelines set out for thesis writing.

Comparatively, a research paper only needs to keep the IMRAD format consistent throughout its length. When planning to publish your research paper in a peer-review journal, you also must follow your target journal guidelines.

3. Time Taken

A thesis is an extensive document encompassing the entire duration of a master's or doctoral course and as such, it takes months and even years to write.

A research paper, being less lengthy, typically takes a few weeks or a few months to complete.

4. Supervision

Writing a thesis entails working with a faculty supervisor to ensure that you are on the right track. However, a research paper is more of a solo project and rarely needs a dedicated supervisor to oversee.

5. Finalization

The final stage of thesis completion is a viva voce examination and a thesis defense. It includes proffering your thesis to the examination board or a thesis committee for a questionnaire and related discussions. Whether or not you will receive a degree depends on the result of this examination and the defense.

A research paper is said to be complete when you finalize a draft, check it for plagiarism, and proofread for any language and contextual errors . Now all that's left is to submit it to the assigned authority.

What is Plagiarism | How to Avoid It

How to Choose the Right Plagiarism Checker for Your Academic Works

5 Practical Ways to Avoid Plagiarism

10 Common Grammar Mistakes in Academic Writing

Guide to Avoid Common Mistakes in Sentence Structuring

In the context of academic writing, a thesis and a research paper might appear the same. But, there are some fundamental differences that set apart the two writing formats. However, since both the documents come under the scope of academic writing, they also share some similarities. Both require formal language, formal tone, factually correct information & proper citations. Also, editing and proofreading are a must for both. Editing and Proofreading ensure that your document is properly formatted and devoid of all grammatical & contextual errors. So, the next time when you come across a thesis vs. research paper argument, keep these differences in mind.

Editing or Proofreading? Which Service Should I Choose?

Thesis Proofreading and Editing Services

8 Benefits of Using Professional Proofreading and Editing Services

Achieve What You Want with Academic Editing and Proofreading

How Much Do Proofreading and Editing Cost?

If you need us to make your thesis or dissertation, contact us unhesitatingly!

Best Edit & Proof expert editors and proofreaders focus on offering papers with proper tone, content, and style of academic writing, and also provide an upscale editing and proofreading service for you. If you consider our pieces of advice, you will witness a notable increase in the chance for your research manuscript to be accepted by the publishers. We work together as an academic writing style guide by bestowing subject-area editing and proofreading around several categorized writing styles. With the group of our expert editors, you will always find us all set to help you identify the tone and style that your manuscript needs to get a nod from the publishers.

English formatting service

You can also avail of our assistance if you are looking for editors who can format your manuscript, or just check on the particular styles for the formatting task as per the guidelines provided to you, e.g., APA, MLA, or Chicago/Turabian styles. Best Edit & Proof editors and proofreaders provide all sorts of academic writing help, including editing and proofreading services, using our user-friendly website, and a streamlined ordering process.

Get a free quote for editing and proofreading now!

Visit our order page if you want our subject-area editors or language experts to work on your manuscript to improve its tone and style and give it a perfect academic tone and style through proper editing and proofreading. The process of submitting a paper is very easy and quick. Click here to find out how it works.

Our pricing is based on the type of service you avail of here, be it editing or proofreading. We charge on the basis of the word count of your manuscript that you submit for editing and proofreading and the turnaround time it takes to get it done. If you want to get an instant price quote for your project, copy and paste your document or enter your word count into our pricing calculator.

24/7 customer support | Live support

Contact us to get support with academic editing and proofreading. We have a 24/7 active live chat mode to offer you direct support along with qualified editors to refine and furbish your manuscript.

Stay tuned for updated information about editing and proofreading services!

Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, and Medium .

For more posts, click here.

- Editing & Proofreading

- Citation Styles

- Grammar Rules

- Academic Writing

- Proofreading

- Microsoft Tools

- Academic Publishing

- Dissertation & Thesis

- Researching

- Job & Research Application

Similar Posts

How to Determine Variability in a Dataset

How to Determine Central Tendency

How to Specify Study Variables in Research Papers?

Population vs Sample | Sampling Methods for a Dissertation

7 Issues to Avoid That may Dent the Quality of Thesis Writing

How to Ensure the Quality of Academic Writing in a Thesis and Dissertation?

How to Define Population and Sample in a Dissertation?

Recent Posts

ANOVA vs MANOVA: Which Method to Use in Dissertations?

They Also Read

Although the rules of English capitalization seem simple at first glance, it might still be complicated in academic writing. You probably know you should capitalize proper nouns and the first word of every sentence. However, in some cases, capitalization is required for the first word in a quotation and the first word after a colon. In this article, you will find 15 basic capitalization rules for English grammer.

Writing an academic paper is not similar to other forms of writing. It requires patience, knowledge, and the use of proper sentence construction. An academic paper should be informative, polished, and well structured. As a student or researcher, you should learn about bad habits and not repeat them in your academic writing. In this article, we discuss 6 bad habits to avoid in academic writing.

Whenever you use words, facts, ideas, or explanations from other works, those sources must be cited. Academic referencing is required when you have copied texts from an essay, an article, a book, or other sources verbatim, which is called quotation. You also need referencing when you use an idea or a fact from another work even if you haven’t used their exact expression.

Writing articles for journals requires scholars to possess exceptional writing skills and awareness of their subject matter. They need to write such that their manuscript relays its central idea explicitly to the readers. In addition, they need to abide by strict writing conventions and best practices to befit the parameters of journal articles. It is not uncommon for research initiates and, at times, even experts to struggle with the article writing process. This article aims to mitigate some apprehension associated with writing journal articles by enlisting and expounding upon some essential writing tips.

After you finish your thesis, what is next is editing your thesis. Rather than sending it to your friends or professors, a better option is to find a professional editing and proofreading service. They usually have trained and experienced experts, have Ph.D. in their fields, and will edit your thesis without prejudice. Their suggestions will improve your thesis's content and structure, rendering it much more effective.

Thesis resource paper You want to do an action research thesis? You want to do an action research thesis? -- How to conduct and report action research (including a beginner's guide to the literature)

Bob Dick [email protected] http://www.aral.com.au/ (An on-line version of this paper can be found at URL http://www.aral.com.au/resources/arthesis.html )

Introduction

What is action research? Characteristics of action research

The advantages and disadvantages

Why would anyone use action research? So why doesn’t everyone use it? Is there some way around this? How do you do action research?

Choosing an approach

Participatory action research Action science Soft systems methodology Evaluation Methods

Carrying out your research project

1 Do some preliminary reading 2 Negotiate entry to the client system 3 Create a structure for participation 4 Data collection

Writing the thesis

Introductory chapter Chapter on methodology Chapters on the thesis contribution Style and fluency In summary...

References and bibliography

[ contents ]

1 The action research cycle consists at least of intention or planning before action, and review or critique after 2 Within each paradigm of research are several methodologies, each drawing on a number of methods for data collection and interpretation 3 Action research often starts with a fuzzy question and methodology; but provided each cycle adds to the clarity, this is appropriate 4 Only overlapping data are considered. If the informants (etc.) are in agreement, later cycles test the agreement; if disagreeing, later cycles attempt to explain the disagreement 5 An expanded version of the intend-act-review cycle 6 Each person’s behaviour may lead to the other person developing unstated assumptions about that person, and inferring unstated rules about their interaction. The result can be a double self-fulfilling prophecy 7 Checkland’s soft systems methodology is here represented as a system of inquiry using a series of dialectics 8 Kolb’s learning cycle 9 The systems model which is the heart of the Snyder approach to evaluation. It is a conventional systems model in which resources correspond to inputs, and activities to processes. There are three levels of outputs, consisting of effects, targets and ideals [ contents ]

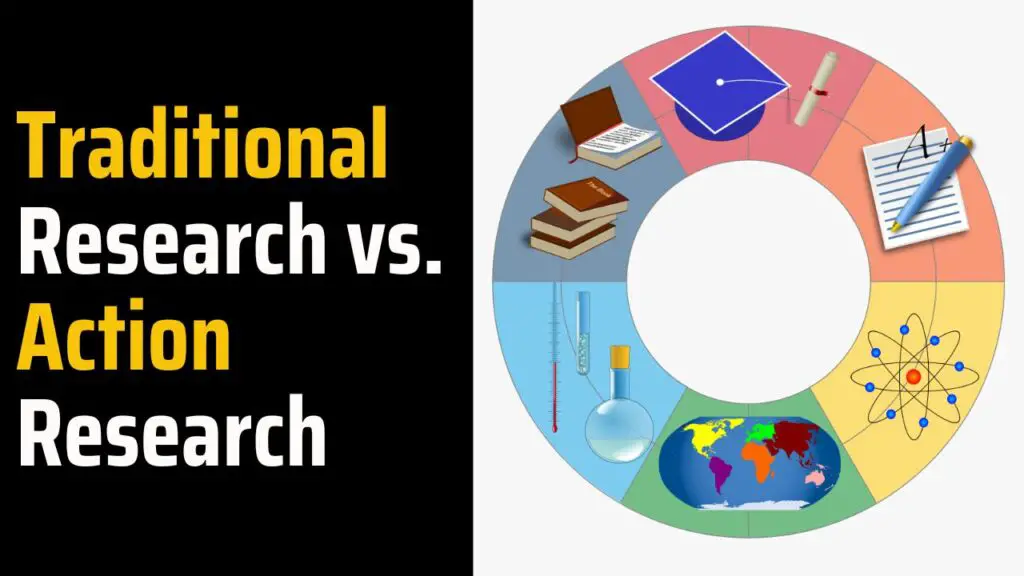

This document begins with a brief overview of action research and a discussion of its advantages and disadvantages. The intention is to help you make an informed choice about your approach to your research. There is a particular focus on doing research for a thesis or dissertation, or for a similar independent research report.

If a thesis is not your interest I think you will still find material of use. The document also includes brief accounts of some of the methodologies that exist within action research. An even briefer mention of the data collection methods which can be used is also included.

This background material is followed by two practical sections. The first of them describes how action research can be carried out. A format for writing up the research is then presented. The form of action research described is one which uses a cyclic or spiral process. It converges to something more useful over time for both action and understanding. It is chosen because of the rigour and economy which it allows. I think it is also more easily defended than some other forms.

I write as a practitioner in a psychology department where action research is viewed with some scepticism. You may be doing your research within a setting where action research and qualitative approaches are more common. If so, you may not need to approach it with quite as much caution as I suggest.

In all of this, it is not my intention to argue against other research paradigms. For some purposes quantitative, or reductionist, or hypothesis-testing approaches, alone or together, are much more appropriate. In many research situations action research is quite unsuitable. My only intention is to offer action research as a viable (and sometimes more appropriate) alternative in some research settings. Should you choose to do an action research study this paper will then help you to do so more effectively and with less risk.

Nor do I have any objection to quantitative research. If your measures adequately capture what you are researching, quantitative measures offer very real advantages. However, qualitative measures may allow you to address more of what you want to examine. In such situations it is appropriate to use them.

The paper is copiously referenced so that you can identify the relevant literature. Embedded in the reference list are also some other works. About half of the references are annotated to assist you in an intelligent choice of reading. The annotations are my own opinion, and might not accord with everyone’s views.

[ contents ]

What is action research?

As the name suggests, action research is a methodology which has the dual aims of action and research...

- action to bring about change in some community or organisation or program

- research to increase understanding on the part of the researcher or the client, or both (and often some wider community)

There are in fact action research methods whose main emphasis is on action, with research as a fringe benefit. At the extreme, the "research" may take the form of increased understanding on the part of those most directly involved. For this form of action research the outcomes are change, and learning for those who take part. This is the form which I most often use.

In other forms, research is the primary focus. The action is then often a by-product. Such approaches typically seek publication to reach a wider audience of researchers. In these, more attention is often given to the design of the research than to other aspects.

In both approaches it is possible for action to inform understanding, and understanding to assist action. For thesis purposes it is as well to choose a form where the research is at least a substantial part of the study. The approach described below tries to assure both action and research outcomes as far as possible. You can modify it in whatever direction best suits your own circumstances.

Characteristics of action research

Above, I defined action research as a form of research intended to have both action and research outcomes. This is a minimal definition. Various writers add other conditions.

Almost all writers appear to regard it as cyclic (or a spiral), either explicitly or implicitly. At the very least, intention or planning precedes action, and critique or review follows. Figure 1 applies.

I will later argue that this has considerable advantages. It provides a mix of responsiveness and rigour, thus meeting both the action and research requirements. In the process I describe below the spiral is an important feature.

For some writers action research is primarily qualitative. Qualitative research can be more responsive to the situation. To my mind a need for responsiveness is one of the most compelling reasons for choosing action research.

Participation is another requirement for some writers. Some, in fact, insist on this. Participation can generate greater commitment and hence action. When change is a desired outcome, and it is more easily achieved if people are committed to the change, some participative form of action research is often indicated.

My own preferences, just to make them clear, are for cyclic, qualitative and participative approaches. However, this is a matter of pragmatics rather than ideology. I see no reason to limit action research in these ways. To my mind it is a stronger option for offering a range of choices.

There are many conditions under which qualitative data and client participation increase the value of the action research. However, to insist on these seems unnecessary. It seems reasonable that there can be choices between action research and other paradigms, and within action research a choice of approaches. The choice you make will depend upon your weighing up of the many advantages and disadvantages.

The advantages and disadvantages

This section describes some of the more important advantages and disadvantages. One of my intentions in doing this is to correct a common misperception that action research is easier than more conventional research. A description of action research then follows. This provides a basis which will be used later to establish ways of maximising the advantages and minimising the disadvantages.

Why would anyone use action research?

There are a number of reasons why you might choose to do action research, including for thesis research...

- Action research lends itself to use in work or community situations. Practitioners, people who work as agents of change, can use it as part of their normal activities . Mainstream research paradigms in some field situations can be more difficult to use. There is evidence, for instance from Barlow, Hayes and Nelson (1984), that most US practitioners do very little research, and don’t even read all that much. Martin (1989) presents similar evidence for Australian and English psychologists. My guess is that they don’t find the research methods they have been taught can be integrated easily enough with their practice. Both the US and Australian studies focussed on clinical psychologists. The argument can probably be made even more strongly for psychologists who work as organisational or community change agents. Here the need for flexibility is even greater, I think. And flexibility is the enemy of good conventional research. Increasingly in Australia, practitioners within academic settings are being pressured to publish more. Those I have talked to report that the research is a heavy additional load: almost an extra job. Action research offers such people a chance to make more use of their practice as a research opportunity.

- When practitioners use action research it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience. The action research cycle can also be regarded as a learning cycle (see Kolb, 1984). The educator Schön (1983, 1987) argues strongly that systematic reflection is an effective way for practitioners to learn. Many practitioners have said to me, after hearing about action research, "I already do that". Further conversation reveals that in their normal practice they almost all omit deliberate and conscious reflection, and sceptical challenging of interpretations. To my mind, these are crucial features of effective action research (and, for that matter, of effective learning).

- It looks good on your resumé to have done a thesis which has direct and obvious relevance to practice. If it has generated some worthwhile outcomes for the client, then that is a further bonus. (There are other research methodologies, including some conventional forms, which also offer this advantage.)

- Action research is usually participative. This implies a partnership between you and your clients. You may find this more ethically satisfying. For some purposes it may also be more occupationally relevant.

So why doesn’t everyone use it?

You may wonder, then, why it is not more common. The main reason, I suspect, is that it isn’t well known. Psychology has ignored action research almost completely. My impression is that there is less debate in academic psychology about research methods and their underlying philosophy than in most other social sciences.

I recall that at the 1986 annual psychology conference the theme was "bridging the gap between theory, research and practice". This was a priority need in psychology, to judge by the choice of theme. Although some of the papers were about applied research in field settings, to my knowledge no paper given at the conference specifically mentioned action research. Yet in action research there need be no gap between theory, research and practice. The three can be integrated.

An ignorance of action research isn’t a reason to avoid it. There are good reasons, however, why you may decide to stay within mainstream research. For example, here are some of the costs of choosing action research as your research paradigm...

- It is harder to do than conventional research. You take on responsibilities for change as well as for research. In addition, as with other field research, it involves you in more work to set it up, and you don’t get any credit for that.

- It doesn’t accord with the expectations of some examiners. Deliberately and for good reason it ignores some requirements which have become part of the ideology of some conventional research. In that sense, it is counter-cultural. Because of this, some examiners find it hard to judge it on its merits. They do not recognise that it has a different tradition, and is based on a methodological perspective and principles different to their own. (At a deeper level some of the differences disappear. Some examiners, however, judge research in terms of more superficial and specific principles.) The danger is that you will receive a lower grade for work of equivalent standard and greater effort. My observation is that some examiners can’t discriminate between good action research and action research which is merely competent. The fact that a study is directly relevant to practitioner psychology and may lead to change does not necessarily carry any weight. Within psychology this is a greater issue for fourth year theses than it is at Masters level and beyond. I suspect it is also more of a source of difficulty in academic psychology than in many other disciplines.

- You probably don’t know much about action research. (Some of you may not think you know much about conventional research either. But you’ve been taught it for 3 or 4 years, or more. You have picked up some familiarity with conventional methods in that time.) Action research methodology is something that you probably have to learn almost from scratch.

- You probably can’t use a conventional format to write it up effectively. Again, that means you have to learn some new skills. In psychology there is a strong expectation that the format recommended by the American Psychological Association (APA) will be used. A non-APA format may alienate some examiners. Again, this may be more of an issue for people working within the discipline of psychology than in some other social sciences. However, most disciplines have their ideologies about how research should be reported.

- The library work for action research is more demanding. In conventional research you know ahead of time what literature is relevant. In most forms of action research, the relevant literature is defined by the data you collect and your interpretation of it. That means that you begin collecting data first, and then go to the literature to challenge your findings. This is also true of some other forms of field research, though certainly not all.

- Action research is much harder to report, at least for thesis purposes. If you stay close to the research mainstream you don’t have to take the same pains to justify what you do. For action research, you have to justify your overall approach. You have to do this well enough that even if examiners don’t agree with your approach, they have to acknowledge that you have provided an adequate rationale. (This may be true for other methodologies outside the research mainstream too.)

- All else being equal, an action research thesis is likely to be longer than a conventional thesis. As already mentioned, you have to provide a more compelling justification for what you do. In effect, you have to write two theses. One reports your method, results and interpretation. The other explains why these were appropriate for the research situation. In addition, if you use qualitative data (and you probably will) that also tends to take more space to report. This is particularly relevant for those of you doing a thesis where page limits or word limits are imposed. If there is such a limit you have to write very succinctly, yet do so without undermining your thesis or your justification.

For most people, these disadvantages outweigh the advantages. Above all, if you are choosing action research because you think it may be an easier option, you are clearly mistaken. I assure you it isn’t. It’s more demanding and more difficult. Particularly at fourth year there is a high risk that you won’t get as well rewarded for it in the mark you get.

I expect that most of you have had a reasonably typical university education. If so, and particularly if you studied psychology, you know enough about conventional research that at least you can do it as a "technician", by following a formula. It’s better to be creative, but you don’t have to be. In action research there isn’t a choice. The demands for responsiveness and flexibility require creativity if the study is to be effective. Yet you have to learn quickly to be a good technician too, so that you do not displease the examiners.

It amounts to this. Whatever research method you use must be rigorous . That is, you must have some way of assuring the quality of the data you collect, and the correctness of your interpretation. You must be able to satisfy yourself and others that the interpretation you offer is consistent with the data. Even more importantly, you have to be able to demonstrate that it is more likely than alternative interpretations would be.

Most conventional research methods gain their rigour by control, standardisation, objectivity, and the use of numerical and statistical procedures. This sacrifices flexibility during a given experiment -- if you change the procedure in mid-stream you don't know what you are doing to the odds that your results occurred by chance.

In action research, standardisation defeats the purpose. The virtue of action research is its responsiveness . It is what allows you to turn unpromising beginnings into effective endings. It is what allows you to improve both action and research outcomes through a process of iteration. As in many numerical procedures, repeated cycles allow you to converge on an appropriate conclusion.

If your action research methodology is not responsive to the situation you can’t aspire to action outcomes. In some settings that is too high a price to pay. You can’t expect to pursue change and do good mainstream research within a single experiment and at the same time.

Good action research is like good social consultancy or community or organisational change. It draws on the same skills and procedures. It offers the same satisfactions. The costs are that it takes time, energy and creativity. And at the end of it you may have to satisfy examiners who are not field practitioners. In fact some of them may not understand and may even be unsympathetic.

Is there some way around this?

Perhaps you are discouraged by now. If so, that’s reasonable -- perhaps even realistic. On the other hand, perhaps for you the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and the thought of a lower grade does not distress you provided you pass. In any event, there are ways in which you can reduce the risk of doing action research. The two most important actions you can take are...

- At all times collect and interpret your data in defensible ways. In particular, know your overall methodology before you begin. At least, know how you intend to start, and check that it is defensible. You will change your mind about your methodology in the light of your experience; but because the changes are motivated by evidence, they too will then be defensible. Always use methods for data collection and interpretation which test or challenge your emerging interpretations. That is, seek out disconfirming evidence . Integrate your library research with your data collection and interpretation. There, too, seek out dis confirmation.

- Justify your methodology carefully in the eventual thesis. Carefully explain your reasons for using action research, qualitative data collection, and the specific methods you use. Be careful to do so without being evangelistic, and without implying even the mildest criticism of other research paradigms.

I will have more to say about each of these later.

It may be that there is enough appeal in the thought of using a research method which suits practitioners. If so, the following account will help you to do so while reducing the risk of displeasing the examiners of your thesis.

I assume in what follows that doing good research is a goal, and that you would prefer to please the examiners at the same time.

How do you do action research?

There are many ways to do action research. It is a research paradigm which subsumes a variety of research approaches. Within the paradigm there are several established methodologies. Some examples are Patton’s (1990) approach to evaluation, Checkland’s (1981) soft systems analysis, Argyris’ (1985) action science, and Kemmis’ critical action research (Carr and Kemmis, 1986). Each of these methodologies draws on a number of methods for information collection and interpretation, for example interviewing and content analysis. Figure 2 summarises the three levels.

These are choices you have to make -- paradigm, methodology, methods. Each choice has to be justified in your eventual thesis. The aim in making the choice is to achieve action and research outcomes in such a way that each enriches the other. That is an important point. Some of the issues which need addressing in the choice are presented clearly in Lawler, Mohrman, Mohrman, Ledford, and Cummings (1985), particularly the introductory paper by Lawler. The illustrative title of the collection of papers is Doing research which is useful for theory and practice .

Below, I describe an approach as one example of how you might go about it. I have chosen it because it is an approach I am familiar with. Also, it achieves a balance of action and research, and it is more economical to report than other approaches I know. The description is quite general, subsuming the methodologies I have already mentioned. The description is step-by-step, to help you to follow it easily.

I want to avoid the style of much of the literature on counter-cultural research approaches. Many of them evangelise for their own particular variety. Consequently they sometimes give the impression that there is one best way to do research, which just happens to be the one they advocate. I think that the approach I describe below is good, or I wouldn’t offer it. I don’t want you to think it’s the only way.

So don’t feel obliged to follow the approach I describe. You can expect to have to tailor it to the research situation. If you can do action research without having to modify it on the run, it probably isn’t the appropriate choice of paradigm. However, most of the steps in the description are there for good reason. If you modify it, be clear about what you are doing, and why you are doing it. Expect that you will have to modify it to respond to the situation. Expect, too, that each modification needs careful choice and justification.

It is important to remember that many examiners are likely to suspect action research of being far less rigorous than more conventional research. It need not be, but much of it in the past has been. Whatever your choice of methods, therefore, focus on rigour: on the quality of your data and your interpretations. The most effective way of doing this, I believe, is to follow two guidelines...

First, use a cyclic (or "spiral") procedure. In the later cycles you can then challenge the information and interpretation from earlier cycles. Both the data you collect, and the literature you read, are part of this. In effect, your study becomes a process of iteration. Within this process you gradually refine your understanding of the situation you are studying. You can think of it in this way... Conventional research works best when you can start with a very precise research question. You can then design a study to answer that question, also with precision. In action research your initial research question is likely to be fuzzy. This is mainly because of the nature of social systems. It is also because you are more likely to achieve your action outcomes if you take the needs and wishes of your clients into account. Your methodology will be fuzzy too. After all, it derives from the research question, which is fuzzy, and the situation, which is partly unknown. If you address a fuzzy question with a fuzzy methodology the best you can hope for initially is a fuzzy answer (Figure 3). This, I think, explains some of the opposition that action research draws from some quarters. But here is the important point...Provided that the fuzzy answer allows you to refine both question and methods , you eventually converge towards precision. It is the spiral process which allows both responsiveness and rigour at the same time. In any event, the whole purpose of action research is to determine simultaneously an understanding of the social system and the best opportunities for change. If you are to be adequately responsive to the situation, you can’t begin the exercise with a precise question. The question arises from the study.

This is the most important reason for choosing action research: that the research situation demands responsiveness during the research project. If you don’t have to be responsive to the situation, I think you would be well advised to save yourself a lot of trouble. Use more conventional research methods.

As it happens, one of the key principles of action research is: let the data decide. At each step, use the information so far available to determine the next step.

Second, at all times try to work with multiple information sources, preferably independent or partly independent. There are ways in which you can use the similarities and differences between data sources to increase the accuracy of your information.

This might be called dialectic . It is similar to what is often called triangulation in research (Jick, 1979). For more background on this important topic you might read some of the material on multimethod research. Examples include Brewer and Hunter (1989), Cohen and Manion (1985), and Fielding and Fielding (1986).

Any two or more sources of information can serve your purpose of creating a dialectic. Here are a few examples. You may use...

different informants, or different but equivalent samples of informants; different research settings (as a bonus, this increases the generalisability of your results); the same informant responding to different questions which address the same topic from somewhat different directions; information collected at different times; different researchers; or, as in triangulation, different methods.

I have described elsewhere a data-collection method, convergent interviewing (Dick, 1990b), which uses paired interviews to create a dialectic. This illustrates the principle. After each pair of interviews, the idiosyncratic information is discarded. Probe questions are then devised for later interviews. Their purpose is to test any agreements by finding exceptions, and to explain any disagreements (Figure 4).

So, for example, if two interviewees agree about X , whatever X is, look for exceptions in later interviews. If the interviewees disagree about X , try in later interviews to explain the disagreement. If only one person mentions X , ignore it.

In effect, treat agreement sceptically by seeking out exceptions. The disagreement between the original data and the exceptions can then be resolved, leading you deeper into the situation you are researching.

It is an important feature of this approach that the later interviews differ from the earlier interviews. This gives you the chance to be suspicious of your emerging interpretation, and to refine your method and your questions. Each interview (or pair of interviews) becomes a turn of the research spiral.

(For an independent assessment of convergent interviewing as a qualitative research tool see Thompson, Donohue and Waters-Marsh (1992).)

What I suggest you do is follow these two groundrules, and explain them clearly in your thesis. You will be less liable to the criticisms which some action research theses have faced in the past.

The purpose in action research is to learn from your experience, and apply that learning to bringing about change. As the dynamics of a social system are often more apparent in times of change (Lewin, 1948), learning and change can enhance each other.

However, you are more likely to learn from an experience if you act with intent. Enter the experience with expectations. Be on the lookout for unmet expectations. Seek to understand them. A different way of describing action research is therefore as an intend Æ act Æ review spiral. A more elaborate form is shown in Figure 5.

It is by being deliberate and intentional about this process that you can maximise your learning. At each of the steps you learn something. Sometimes you are recalling what you think you already understand. At other steps you are either confirming your previous learning or deciding from experience that your previous learning was inadequate.

This is equivalent to what Gummesson (1991) calls the "hermeneutic spiral", where each turn of the spiral builds on the understanding at the previous turn. It is these -- the responsiveness to the situation, and the striving after real understanding -- which define action research as a viable research strategy.

This helps to explain why action research tends also to be qualitative and participative. In quantitative research you often have to give a fair amount of time and attention to the development of an appropriate metric or system of measurement. Every time you change your mind about your research question you risk having to modify your metric.

Participation favours qualitative methods. Participation by the client group as informed sources of information gives you a better chance of discovering what they know and you currently do not. They are more likely to join you as equal partners in this endeavour if you speak to them in their own language (for instance, everyday English) than in numbers or technical language.

In addition to gaining some background knowledge of action research, you also need enough prior information to enable an intelligent choice of methodology. The following section describes four action research methodologies.

As I have said, there are paradigms (such as action research), methodologies (soft systems analysis, for example), and methods. You will change your mind during the course of the study about methods, so you need not concern yourself too much about them now. You may even change the methodology you use; but it doesn’t hurt to begin by choosing one as the possible vehicle for your study.

There are advantages in following a published approach. In particular it can be simpler to use a process described by an author who has sufficiently explained and justified it. In your eventual thesis it is then someone else who is providing much of the justification for what you do. This is less risky than having to provide it yourself.

By the way, I do not think you should accept anyone else’s arguments uncritically. Satisfy yourself that the argument is well made. Better still, suggest some improvements.

Below, I give brief accounts of four methodologies. One is participatory action research, to some extent in the style of the "critical action research" of Kemmis and his colleagues at Deakin University (Carr and Kemmis, 1986; Kemmis and McTaggart, 1988). A second is action science as developed by Argyris and his colleagues (for example Argyris, Putnam and Smith, 1985). Checkland’s (1981) soft systems methodology comprises the third. The fourth, evaluation, is itself a large family of methodologies. I draw to some extent on the work of Patton (for example, 1990) and Snyder (personal communication). I do not assume that the developers of these methodologies would necessarily agree with my summary of them.

Participatory action research

The action research literature is reasonably large, and growing. It is often characterised by process-oriented, practical descriptions of action research methods. Action research in education, in particular, is common. To select from the large number available, I might mention as examples Elliott (1991), McKernan (1991), and Winter (1989). Each of these is written from a different perspective.

A number of works which use the Deakin model provide useful reading. Kemmis (1991) is one. Ortrun Zuber-Skerritt (1992a, 1992b) has recently published two books in this tradition.

You may also want to supplement your reading from works on qualitative research generally. Examples here include Gummesson (1991), Marshall and Rossman (1989), or Strauss and Corbin (1990). Marshall and Rossman is a good starting point. Whyte (1991) contains a collection of papers mostly illustrating participatory action research with case studies done in a variety of settings.

If you look at the bibliography you will find that three publishers in particular, Falmer and Kogan Page in England and especially Sage in the US, specialise in qualitative research. Most of their publications (or at least those I’ve seen) are well written and useful.

When it comes to justifying your use of action research, I think the first half of Checkland (1981) provides a more coherent argument than most of the others. (Not everyone agrees with me about this). Although he is describing soft systems methodology, described below, he explicitly identified it as an action research methodology (Checkland, 1992). In his keynote address to the Action Learning Congress in Brisbane in 1992 he argued that a legitimate rigorous action research methodology requires an explicit methodological framework. I agree. He claims most action research ignores this requirement.

In addition, Checkland uses language which will be less of a challenge to the expectations of examiners unfamiliar with action research. In contrast, the arguments of Kemmis and his colleagues (see below), and many other writers in the field, are occasionally polemical enough to stir defensiveness. I advise caution in their use.

There is also good material in some of the papers in the collection edited by Van Maanen (1983). Van Maanen’s own introduction and epilogue provide good starting points.

The form of action research taught at Deakin University by Stephen Kemmis and Robin McTaggart provides a framework. There are several sources, but particularly Carr and Kemmis (1986), and Kemmis and McTaggart (1988). If your examiners are familiar with action research, it may well be that this is the form they know best. Deakin also offers a distance education course in action research, reported electronically by McTaggart (1992).

The Deakin University people work with a particular form of action research, and tend to be critical of other approaches. If you use their method, it would be as well to document and argue for any deviations. As I said above, they also often argue more on ethical than epistemological grounds, and somewhat evangelically. Your best strategy for thesis purposes may be to use their processes, which are effective and well explained. However, it may be better to find your arguments elsewhere.

To help you place their approach in context, you may also want to read Grundy (1982, 1987). This will help you distinguish the Deakin approach from some of its alternatives. In addition, McTaggart (1991) has written a brief history of action research, with a particular emphasis on educational settings.

The essence of the Deakin approach is the use of a defined cycle of research, and the use of participatory methods to produce "emancipation". They call their approach emancipatory action research, and draw on European sources, especially on the critical theory of the Frankfurt school. The cycle or spiral which they describe consists of four steps: plan, act, observe and reflect.. This cycle is carried out by the participants -- they conceive of action research as something done by the clients, not something done to the clients by a researcher. To my mind one of the strengths of their approach is the emphasis on research which liberates those who are researched.

Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) provide a description of the Deakin approach. Zuber-Skerritt (1992a, 1992b) uses a similar framework. She draws heavily on Kemmis’ work, also relating it to other (especially European) literatures. Anything by Richard Bawden, who runs a whole faculty on action research principles at the Hawkesbury campus of the University of Western Sydney, is likely to contain a thoughtful and well-argued commentary (for example Bawden, 1991). His approach is in most respects consistent with that of the Deakin team. Denham (1989) has done a coursework masters dissertation using action research, though not in the Deakin style.

Participatory action research is a generic methodology. You could treat it as a back-up position for some other approach if you wished. It might also be a good choice if the research situation appears too ambiguous to allow a more specific choice.

The next methodology, action science, is more specific.

Action science

For some decades now, Chris Argyris has been developing a conceptual model and process which is at the one time a theory of social systems and an intervention method. It is particularly appropriate to the researching of self-fulfilling prophecies, system dynamics based on communication flows, and relationships.

The central idea is that, despite their espoused values, people follow unstated rules. These rules prevent them behaving as they might consciously wish. The result is interpersonal and system processes in which many problems are concealed. At the same time, taboos prevent the problems or their existence being mentioned. In effect, the unstated rules of the situation, and the unstated assumptions people form about each other, direct their interactions in both group and organisational settings (Figure 6).

I know of no other system which integrates in so well-argued a fashion interpersonal, intrapersonal and system dynamics, and processes for research and intervention. As Argyris presents the approach it does depend on high quality relationships between researcher and client, and skilled facilitation. However, there are alternatives in the form of detailed processes which clients can manage for themselves. These processes are directed towards the same improvement in the social systems and the understanding of the actors as in Argyris’ own work (see Dick and Dalmau, 1990). They have been used in one action research thesis to my knowledge, Anderson (1993).

The concepts are developed in Argyris and Schön (1974, 1978). The 1974 book deals primarily with the effects of intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics on social systems. The later book focuses more deliberately on system dynamics. Argyris’ 1980 book provides much of the rationale, as do some of his earlier works.

Many people find this material hard to read. Argyris (1990) is easier to follow. People have told me that a book Tim Dalmau and I wrote (Dick and Dalmau, 1990) sets out the concepts well. If you can get hold of Liane Anderson’s (1993) thesis, it contains a very clear overview. Your understanding of the relevant system dynamics may be helped by Senge (1990), who describes system functioning in terms of interaction cycles. Most people find Senge more readable than Argyris (though it is my view that in some respects Senge’s book lacks Argyris’ depth).

The research methodology is most clearly described in Argyris, Putnam and Smith (1985). It is also worth browsing through Argyris (1985), which was written for consultants. (This is an action research project and action implies intervention.) Argyris’ 1983 paper is also relevant.

Argyris, too, is evangelical about his approach, and criticises other research methods. If you use his own arguments you may have to be careful to avoid offending some readers.

There isn’t a simple way to describe the methodology. Essentially it depends upon agreeing on processes which identify and deal with those unstated rules which prevent the honest exchange of information. The diagram above can be used as a model for the type of information to surface. There is a strong emphasis on the people involved in the research being honest about their own intentions, and about their assumptions about each others motives. You can think of it as providing a detailed set of communication processes which can enhance other action research approaches.

I have treated action science as action research. However, note the view expressed by Argyris and Schön (1989, 1991). While acknowledging action science as a form of action research they identify an important difference in focus. In particular, Argyris has argued here and elsewhere that normal social research is not capable of producing valid information. Without valid information the rigour of any action research endeavour is necessarily undermined. As I understand him, he believes that action science is a research method which is capable of obtaining valid information about social systems where most other research methods, action research or otherwise, would fail.

Action science is a good choice of methodology if there are strong within-person and between person dynamics, especially if hidden agendas appear to be operating. However, it probably requires better interpersonal skills and willingness to confront than do the other methodologies described here. You can use a pre-designed process, but unless you sacrifice some flexibility you still require reasonably good skills.

Soft systems methodology, which follows, is somewhat less demanding in terms of the interpersonal skills it requires.

Soft systems methodology

Soft systems methodology is a non-numerical systems approach to diagnosis and intervention. Descriptions have been provided by Checkland (1981, 1992), Checkland and Scholes (1990), Davies and Ledington (1991), and Patching (1990). The book by Davies and Ledington is a good starting point. It also has the advantage that both authors are now in Brisbane. Lynda Davies is at QUT, and Paul Ledington is in the Department of Commerce at the University of Queensland. Patching’s description is very practical. He provides a complementary description, as he writes as a practitioner. The other writers are academics. Jackson (1991) has provided a critique, partly sympathetic, of soft systems methodology and related approaches.

In the description which follows, I will first outline an inquiry process which stresses the notion of dialectic rather more than the descriptions given by the authors cited above. I then explain the specific features of soft systems methodology. In doing this I use the framework which this inquiry process provides.

One form of inquiry process consists of three dialectics. In each dialectic you (or the researchers) alternate between two forms of activity, using one to refine the other. Figure 7 outlines the process as a series of dialectics.

- To begin you immerse yourself in the reality, in a style akin to participant observation (as described, for example, in Lofland and Lofland, 1984). You then try to capture the essence of the system in a description, probably in terms of its most important functions. Then switch between reality and your description of that reality. This is the first dialectic.

- The next dialectic is between the description of the essence, and a depiction of an ideal. The description of the essence you already have, from the first dialectic. You then forget your experience of the reality. Working from the description of the essential functions, devise an ideal system. Alternate between them until you are satisfied that your ideal achieves the essential functions of the system.

- The third is between the ideal and reality. You compare your ideal to the actual system, noting differences. This third dialectic gives rise to a set of proposals for improvement to the reality. This leads in turn to action, which is a dialectic between plans and reality, and is a fourth step.

The diagram may make this clearer. In more detail...

- First you immerse yourself in the system, soaking up what is happening. From time to time you stand back from the situation. You reflect on your immersion, trying to make sense of it. At these points you might ask: what is the system achieving or trying to achieve? When you return to immersion you can check if your attributed meaning adequately captures the essentials. This continues until you are content with your description of the essential functions.

- You then forget about reality, and work from your description of its essential functions. You devise the ideal system or systems to achieve the system’s actual or intended achievements. Moving to and fro between essence and ideal, you eventually decide you have developed an effective way for the system to operate.

- The third step is to compare ideal and actual. Comparisons may identify missing pieces of the ideal, or better ways of doing things. The better ways are added to a list of improvements.

- Finally, the feasible and worthwhile improvements are acted on, forming the fourth dialectic.

- In passing, you may note the resemblance of this to Kolb’s (1984) learning cycle (Figure 8). His four-element cycle consists of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract generalisation, and active experimentation.

It is typical for each cycle in soft systems methodology to take place several times. A better understanding develops through these iterations. If there is a mismatch between the two poles of a dialectic, this leads to a more in-depth examination of what you don’t understand. Continuing uncertainty or ambiguity at any stage may trigger a return to an earlier stage.

To give more impact to the third dialectic, the first dialectic can be put deliberately out of mind when the second dialectic is current. In other words, when you are devising the ideal, try to forget how the actual system operates. In this way, the ideal is derived from the essence, to reduce contamination by the way the system actually behaves. The comparison of ideal and actual then offers more points of contrast.

I have taken some pains to describe the process as an inquiry process. If you wished you could use models other than systems models within the process. What converts this inquiry system into a soft systems analysis is the use of systems concepts in defining the essence and the ideal.

In systems terminology the essence becomes the necessary functions. Checkland calls them root definitions. To check that they are adequate he proposes what he calls a Catwoe analysis. Catwoe is an acronym for...

C ustomers A ctors T ransformation (that is, of system inputs into outputs) W eltanschauung (or world view) O wners, and E nvironmental constraints.

The ideal, too, is conceived of in systems terms by devising an ideal way of transforming the inputs into outputs. Systems models help to suggest ways in which the different goals of the studied system can be achieved.

In his earlier work Checkland described this as a seven-step process. The steps are...

(1) the problem unstructured; (2) the problem expressed; (3) root definitions of relevant systems; (4) conceptual models; (5) compare the expressed problem to the conceptual models; (6) feasible and desirable change; and (7) action to improve the problem situation.

Soft systems methodology is well suited to the analysis of information systems. This has been the thrust of the works I mention earlier, though I wouldn’t limit it to that application. For an example of a dissertation using it in agriculture see van Beek (1989). Reville (1989) has used it to evaluate a training scheme. It seems to lend itself to the analysis of decision-making systems generally.

The next subsection deals with a more generic methodology: evaluation.

It is misleading to characterise evaluation as a single methodology. There is probably far more written on evaluation alone than on all (other) action research methodologies combined. The approaches vary from those which are very positivist in their orientation (for example, Suchman, 1967) to those which are explicitly and deliberately anti-positivist (such as Guba and Lincoln, 1989). For thumbnail sketches of a variety of approaches, ranging in length from a paragraph to several pages, see Scriven’s (1991) aptly named Evaluation thesaurus .

As is often so when people have to deal with the complexities of reality, the change in methodology over time has been mostly from positivism to action research and from quantitative to qualitative. Cook and Shadish (1986) summarise the trends, explain the reasons for the shift from positivism, and in doing so provide some useful background. Yes, it is the same Cook who wrote on quasi-experimentation (Cook and Campbell, 1979). This is one of the fringe benefits of using an evaluation methodology -- you can support your justification of your methodology with quotes from people who are well regarded in traditional research circles. Cronbach (Cronbach, Ambron, Dornbusch, Hess, Hornik, Phillips, Walker, and Weiner, 1980) and Lawler (Lawler et. al., 1985) are other examples.

There is a sense in which the distinction between evaluation and some other processes is artificial. If you are working within an action research framework then appropriate diagnostic methods can be used for evaluation. So can appropriate evaluation methods be used for diagnosis. In both instances the situation is analysed with a view to bringing about change. A fourth year research project by Reville (1989) has used soft systems methodology successfully as an evaluation tool. Bish (1992), in a coursework masters dissertation, used a general action research approach for evaluation of a fourth year university course.

Two writers who provide a copious justification for their approach to evaluation are Patton (for instance 1982, 1986, 1990) and Guba (1990; Guba and Lincoln, 1981, 1989; Lincoln and Guba, 1985). Of the two, Guba provides the more detailed description of how evaluation can be done. The approach is also a little more carefully argued, though too polemical to be used carelessly.

My own preferred approach is based on an evaluation model developed by Snyder (personal communication), who once lectured at the University of Queensland. I have been developing it into a more systematic process while preserving its responsiveness. It is so far unpublished, though I can provide you with some papers on it (Dick, 1992a, among others). It has been used in a number of settings and has featured in a coursework masters thesis by Bell (1990).

However, if you use the Snyder model or other goal oriented models be aware of the debate about goals. Scriven (1972) and Stufflebeam (1972) between them cover the essentials. Then use Scriven’s (1991) entry on goal-free evaluation to bring you up to date.

A brief description of a Snyder evaluation follows...

The Snyder "model" actually consists of a content model based on systems concepts and a number of processes. The content model has inputs (known as resources), transformations (activities), and three levels of outputs: immediate effects, targets, and ideals. Figure 9 shows it diagrammatically.

The processes allow you to address three forms of evaluation in sequence. Process evaluation helps you and your clients to understand how resources and activities accomplish immediate effects, targets and ideals. Outcome evaluation uses this understanding to develop performance indicators and use them to estimate the effectiveness of the system. Short-cycle evaluation sets up feedback mechanisms to allow the system members to continue to improve the system over time.

If done participatively the process component leads to immediate improvement of the system. As the participants develop a better understanding of the system they change their behaviour to make use of that understanding. The outcome component can be used to develop performance indicators. The short-cycle component in effect creates a self-improving system by setting up better feedback mechanisms. You can think of it as a qualitative alternative to total quality management.

Whatever the methodology you choose, you will require some means for collecting the information. I won’t go into these in detail here, but will briefly mention some of the methods and some of the sources.

Firstly, two data collection methods have a strong dialectic built into them. One is convergent interviewing (Dick, 1990b). The second is delphi, a way of pooling data from a number of informants. It is usually done by mail; this makes the process easier to manage, though at the cost of reducing participation. It is described in some detail by Delbecq, Van de Ven and Gustafson (1986). Their brief and readable book also describes nominal group technique, which is a group data-collection process which allows all views to be taken into account. To alert you to the dangers in using delphi there is a biting critique by Sackman (1975). A briefer and more sympathetic account appears in Armstrong (1985). For a recent example of a research masters thesis in social work using a mail delphi see Dunn (1991).

I have described (Dick, 1991) a face-to-face version of delphi, though one which requires more skilled facilitation than the mail version. This same book, on group facilitation, contains descriptions of a number of methods for collecting and collating information in group settings.

A further dialectic process, though not usually described in those terms, is conflict management or mediation. This is a process, or rather a family of processes, whose purpose is to reach agreement in situations characterised by disagreement. You can therefore regard conflict management as a set of processes for data collection and interpretation. One of the clearest process descriptions is in Cornelius and Faire (1989).

A further technique which can be turned easily into a dialectic process is group feedback analysis. Heller, who devised it, has described it in a number of papers (for example 1970, 1976). For other specific techniques you might consult McCracken (1988) on the long interview, and Morgan (1988) on focus groups. You have to build your own dialectic into these methods. Heller’s approach sacrifices responsiveness to standardisation, to some extent. It is not difficult to modify it to give it whatever emphasis you desire.

There are a number of recent general accounts of qualitative methods. Miles and Huberman (1984) focus primarily on methods for analysing qualitative data. Walker (1985), Van Maanen (1983), and Rutman (1984) present collections of papers, many of which are helpful in choosing methods. Market research techniques, for example as described by Kress (1988) can often be pressed into service. Gummesson (1991) takes a more macro approach with a particular emphasis on managerial settings.

Practical works on group facilitation can also be helpful. For example you might try Heron (1989), or Corey and Corey (1987). My book entitled Helping groups to be effective (Dick, 1991) is also relevant. It has quite a lot on methods of collecting and collating data in group settings.

[ contents ]

In this section I provide a description of the major phases of an action research project.

In doing this I don’t want to give the wrong impression. So please note that it isn’t going to be as simple in practice as my description may imply. You are likely to find that the steps overlap, and on occasion you may have to revisit early steps to take account of later data collection and literature. Think of it as consisting of cycles within cycles.

However, there are some broad stages. They are described immediately below...

1. Do some preliminary reading

Reading about action research continues throughout the study, but it’s useful to have some idea of action research before you actually approach a client. If you have no idea what you are going to do, you may find it hard to explain to others.

If you choose the reading carefully, it can also be preparation for the introduction to your thesis. In fact, it’s a good idea to start writing your introduction. In that way you can check that you can provide an adequate justification. It would be a shame if you decided after it was all over that you didn’t choose an appropriate approach.

At this stage, most of your reading is in the methodological literature. The content literature comes later, as you collect and interpret some of your data. If you are definitely researching a particular content area you will need to scan the more important literature in the field. For the most part, however, reading in the content literature at this stage can be wasted if the research takes off in a different direction.

In approaching the methodological literature, look for arguments you can use to justify your approach. At the same time, notice any approaches which seem to suit your intended research situation.

To begin to access the literature, you might begin with the first half of Checkland’s (1981) book on soft systems methodology. It provides a clear justification for using an action research approach in language which won’t distress people from a more traditional research background. Some of the chapters in Van Maanen (1983) are also appropriate.

To give you some background on the use of qualitative data, you will probably find Patton (1990) valuable. So is Kirk and Miller (1986). Rigour without numbers (Dick, 1990a) is useful and presents a somewhat different view.

For a general overview, Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) is valuable. Beware, though, that they have narrow ideas about what is acceptable as action research. Altrichter (1991) argues that action research has strong similarities to conventional research. This may help you to make your research approach less alienating for an examiner. For general background it may also be worth your while to skim Guba (1990). But be careful about using the arguments from this book, as they tend to be polemical. Phillips (1992) identifies some of the weaknesses in Guba’s arguments.

Action research, as I’ve said, is action and research. The literature on intervention is therefore relevant. A good starting point is Guba and Lincoln’s (1989) book on evaluation. Their "fourth generation evaluation", as they call it, is an evaluation technique which is clearly similar to action research. It integrates research and intervention systematically and well. Again, the arguments are somewhat polemical. French and Bell (1990) write on organisational change from an explicit action research perspective. Dunphy (1981) deals well with change techniques, in a book written specifically to integrate concepts and practice. It has the added advantage that it was written for Australian conditions. However (in my mind narrowly) it criticises general systems theory as a basis for theorising about change. Cummings and Huse (1989) describe organisational change in a way which relates it more directly to the academic research literature. This can be useful.

If your interest is more in community change try Cox, Erlich, Rothman, and Tropman (1987). Don’t overlook Rogers (1983) and his collation of a massive literature on change and innovation. Although directed primarily towards rural innovation it draws on a wider literature than that, and has wider application. It is a very good resource. I hope a new edition appears soon.

You will eventually want to read about specific methods. For the most part, however, this can probably wait until you are a little further into the actual study. The reading I’ve suggested in this section will get you started. You can then return to the earlier sections of this paper or the appended bibliography for further reading.

In addition, Miles and Huberman (1984) may help you to gain some idea of the possibilities for collecting and analysing data. A general text on action research or qualitative research may be worth skimming. You can choose from Crabtree and Miller (1992), van Maanen (1983), Whyte (1991), Strauss and Corbin (1990), Walker (1985), or Reason (1988), among others. Have a look at their titles (and for some the annotations) in the bibliography below, to help you choose.

It is important not to limit your reading to those people whose ideas you agree with. Some examiners will judge your final thesis from within their own paradigm. To address their concerns you have to understand their ideology as well as your own. Presumably most of you already have some exposure to this literature from your prior study of the social sciences. However, it won’t hurt to refresh your memory. You will find Campbell and Stanley (1963) useful reading on the threats to validity you have to deal with. Cook and Campbell (1979) can then provide a valuable supplement to this. Black and Champion (1976) also provide a traditional view. For a more recent view, try Stone (1986).

If you are a bookworm, you will develop some useful background understanding by exploring some philosophy of science. Kuhn (1970) is vintage. Lakatos (1972) and Feyerabend (1981) will help you develop an understanding of the way all research paradigms have their Achilles’ heel. If you don’t want to read them in the original, Chalmers (1982, 1990) provides a critical but fair overview together with an account of other views. I find him one of the most readable of philosophers.

Phillips (1992), in an eclectic, reasoned and often entertaining book, points out the weaknesses in several approaches. He also provides a summary of current views in the philosophy of science. Even if you don’t read anything else on the philosophy of science his chapter on qualitative research is well worth studying.

To prepare for the eventual thesis, look beyond the differences to the underlying issues. If you can phrase your justification of action research in terms of different trade-offs in different paradigms you may find it easier to support your research processes without appearing to criticise other approaches. There is more on this below.

2. Negotiate entry to the client system

As well as the general reading on action research, you will find it useful to read something on entry and contracting before you actually enter the client system. You might choose from the following. Dougherty (1990) is a general introduction to organisation development which has a section on entry. Glidewell (1989) focuses on issue entries. In another paper in the same book Schatzman and Strauss (1989) deal with the important topic of creating relationships in consulting. My favoured book in the area is Hermann and Korenich (1977), despite its age. Argyris’ work is relevant too, for instance his 1990 book; but it’s not something to try to understand in just a day or two.

A collection of papers which focus on field research has been compiled by Shaffir and Stebbins (1991). The first of four parts is on entry. Each of the other parts gives attention to the importance of forming relationships. The approach is mostly ethnographic, but many of the practices translate easily enough into the type of research I’m discussing here.

Obviously enough, your intention during the entry phase is to negotiate something which is mutually beneficial for you and the client system. What may be less obvious, and certainly more difficult, is to negotiate a fair amount of flexibility in what you do, and your role. Without flexibility you sacrifice some of the advantages of the action research methodology.

3. Create a structure for participation

In much action research the intention of the researcher is to create a partnership between herself and the client group. That can increase the honesty with which the clients report information -- it’s in their benefit, too, to have accurate information. It almost always increases the commitment of the client group to the changes which emerge from the research.

In some situations you may be able to involve all of those who have an interest in the situation -- the "stakeholders", as they are usually called. In other situations you may have to be satisfied with a sample. And occasionally it may only be feasible to use the stakeholders as informants, without involving them any more directly in the process.

Choosing an appropriate sample is not always easy. You may find a "maximum diversity" sample, in which you try to include as much diversity as you can, will give you better information for a given size. In random samples, especially small ones, the extreme views tend to be under-represented. You are less likely to miss important information if you include as many views as possible. In addition, dialectic works better if there is adequate variety in the information analysed.

You can often achieve a real partnership with the client group even when you have to work with a sample. A convenient practice is to set up a steering committee with a small sample. They become directly involved with you. They can also help you to choose others as informants, and to interpret the information you get. However, before you actually start on this, give some attention to your relationship with them, and their and your roles. Also agree on the processes you will use together. Remember to be flexible and to negotiate for ample continuing flexibility.

There is some literature on the value of participation in action research. It is often less explicit about how you would actually do it. A commendable exception is Oja and Smulyan (1989). For the most part you will have to make do with the literature mentioned in step 2, previously.

4. Data collection

If this were a conventional piece of research you would expect to collect all the data first. Only when data collection was complete would you do your analysis. Then would follow in turn interpretation and reporting.