Competencies for Public Health Professionals

- Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals

- Use of the Core Competencies

- Select Public Health Workforce Competency Frameworks

Competencies are the knowledge, skills, abilities, and behaviors that contribute to individual and organizational performance. In public health, successful mastery of competencies is vital to developing a strong workforce that can support community and program needs. Public health agencies and organizations can use competencies to

- Develop job descriptions

- Assess knowledge and skills that contribute to job performance

- Identify critical gaps in training

- Create career paths

- Inform workforce development plans

- Support efforts to meet accreditation standards

The Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals (Core Competencies) are a framework for workforce development planning and action. The Core Competencies are defined as “a consensus set of knowledge and skills for the broad practice of public health, defined by the 10 Essential Public Health Services .” They can serve as a starting point for public health professionals and organizations working to better understand and meet workforce development needs, improve performance, prepare for accreditation, and enhance the health of the communities they serve.

The Core Competencies have a long history in supporting workforce efforts in public health practice and academic settings. They were initially developed in 1991 by the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice (Council on Linkages), a collaborative of national public health practice-based and academic organizations . The current version of the Core Competencies was adopted by the Council on Linkages on October 21, 2021, following a yearlong review and revision process.

The Healthy People Public Health Infrastructure Topic Area —coordinated by CDC’s National Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Public Health Infrastructure and Workforce ( Public Health Infrastructure Center ) and the Health Resources and Services Administration—includes objectives focused on use of the Core Competencies by state, local, territorial, and tribal health departments. These objectives were included in Healthy People 2020 and have been retained as Public Health Infrastructure core objectives in Healthy People 2030 .

Competency sets are often used by learning management systems and training platforms to help users identify offerings that meet their needs. TRAIN is a learning management platform supported by the Public Health Foundation and used by CDC via CDC TRAIN and other public health agencies and organizations. TRAIN users can find trainings based on a specific tier or domain of the Core Competencies and other select competencies sets using the “Competencies and Capabilities” feature.

Public health agencies and organizations use the Core Competencies to better understand, assess, and meet their education, training, and other workforce development needs. Some of these uses include

- Identifying and meeting training gaps

- Assessing workforce development needs

- Determining competency strengths and areas for improvement in organizational and individual performance evaluations

- Developing quality trainings

- Identifying mentoring and coaching opportunities

- Writing job and position descriptions

- Addressing workforce-related national accreditation standards (see Domain 8 of Public Health Accreditation Board Standards & Measures)

The Public Health Foundation’s website provides many tools that can be adapted and includes examples of how organizations use the Core Competencies.

Public health organizations use a variety of discipline-specific competency frameworks in addition to the Core Competencies. The list below is not exhaustive but includes many competency models that support and advance public health workforce efforts.

- Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals Council on Linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice (Council on Linkages) (Latest edition: 2021)

- Competencies for Performance Improvement Professionals in Public Health (PI Competencies) Council on Linkages (Latest edition: 2018)

- Public Health Law Competency Model: Version 1.0 [PDF – 1.406 KB] CDC’s Public Health Law Program (Latest edition: 2016)

- Legal Epidemiology Competency Model Version 1.0 CDC’s Public Health Law Program (Latest edition: 2018)

- Public Health Emergency Law Competency Model Version 1.0 CDC’s Center for Preparedness and Response and CDC’s Public Health Law Program (Latest edition: 2013)

- Applied Epidemiology Competencies CDC and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (Latest edition: 2023)

- Community/Public Health Nursing Competencies [PDF – 668 KB] The Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations (Latest edition: 2018)

- Competencies for Population Health Professionals Association for Community Health Improvement, Catholic Health Association, Council on Linkages, Association of American Medical Colleges, and Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (Latest edition: 2019)

- Environmental Health Competencies The American Public Health Association with support from CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health (Latest edition: 2020)

- Applied Public Health Informatics Competency Model [PDF – 399 KB] The Informatics Academy at the Public Health Informatics Institute (Latest edition: 2016)

- Immunization Information System (IIS) Core Competency Model Public Health Informatics Institute with support from CDC (Latest edition: 2021)

- Including People with Disabilities: Public Health Workforce Competencies A national committee comprised of disability and public health experts with support from CDC (Latest edition: 2016)

- Responsibilities and Competencies for Health Education Specialists The National Commission for Health Education Credentialing, Inc. (Latest edition: 2020)

- Competency Guidelines for Public Health Laboratory Professionals CDC and the Association of Public Health Laboratories (Latest edition: 2015)

- Public Health Associate Program (PHAP) Cohort Competencies CDC’s Public Health Infrastructure Center (Latest edition: 2020)

- Accreditation Criteria: Schools of Public Health & Public Health Programs – includes MPH and DrPH foundational competencies The Council on Education for Public Health (Latest edition: 2021)

- Racial Justice Competencies for Public Health Professionals The Public Health Training Center Network in partnership with the National Network of Public Health Institutes (Latest edition: 2022)

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Health Communication

- Healthcare Management

- Global Health

- Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

- Choose a Public Health Degree Based on Your Personality

- Public Health vs. Medicine vs. Nursing

- What is Online Learning

- Master’s in Health Informatics vs. Health Information Management

- MPH vs. MSPH vs. MHS

- Online MPH programs with no GRE requirements

- Accelerated Online MPH

- Online Executive MPH

- Online DrPH

- Biostatistics

- Community Health and Health Promotion

- Environmental Health

- MPH in Epidemiology vs. Biostatistics

- Generalist Public Health

- Health Equity

- Health Science

- Health & Human Services

- Infectious Disease

- Maternal & Child Health

- Occupational Health

- Social and Behavioral Health

- What Can You Do With a Public Health Degree?

- How to Be a Good Candidate for a Public Health Job

- How to Become a Biostatistician

- How to Become an Emergency Management Specialist

- How to Become an Environmental Health Specialist

- How to Become a Health Educator

- Healthcare Administration Certifications

- Healthcare Administrator Salary

- Types of Epidemiologists and Salary

- How to Become an Occupational Health and Safety Specialist

- How to Become a Public Health Nurse

- Nutritionist vs Dietitian

- Registration Examination for Dietitians (CDR Exam)

- Internships for MPH Students

- Health Informatics Careers and Jobs

- Health Informatics vs. Bioinformatics

- Guide to CDC Jobs

- Massachusetts

- North Carolina

Home » Resources

Public Health Core Competencies

September 14, 2020

Public health professionals focus on making the lives of other people and their communities better. They concern themselves with many factors that play a role in the health of humans, such as the environment, public policy, health care and laws. If you are interested in taking on a public health role and are looking for an appropriate graduate program, a master’s degree might be an ideal way to achieve your goal.

As an MPH student, you will be guided by 22 foundational core public health competencies (PDF, 406 KB) set forth by the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH). Here is a closer look at these core competencies for public health professionals and why they are essential.

Simmons University

Department of public health.

Women with 17+ prior college credits or an associate degree: Complete your bachelor’s degree in a supportive women’s online public health BS program.

- Up to 96 transfer credits accepted, plus credit for life experience

- Degree programs are designed for working professionals and can be completed part time

- CEPH-accredited

info SPONSORED

Definition of Core Competencies

Core competencies are difficult to mimic. They are the fundamental knowledge, skills and attributes a person or organization holds that allow an individual or company to succeed and grow. What are core competencies in public health?

In the public health sector, core public health competencies allow the workforce to operate effectively and carry out the core functions of public health , including population health assessment, monitoring, health promotion, disease and injury prevention, health protection and emergency preparedness.

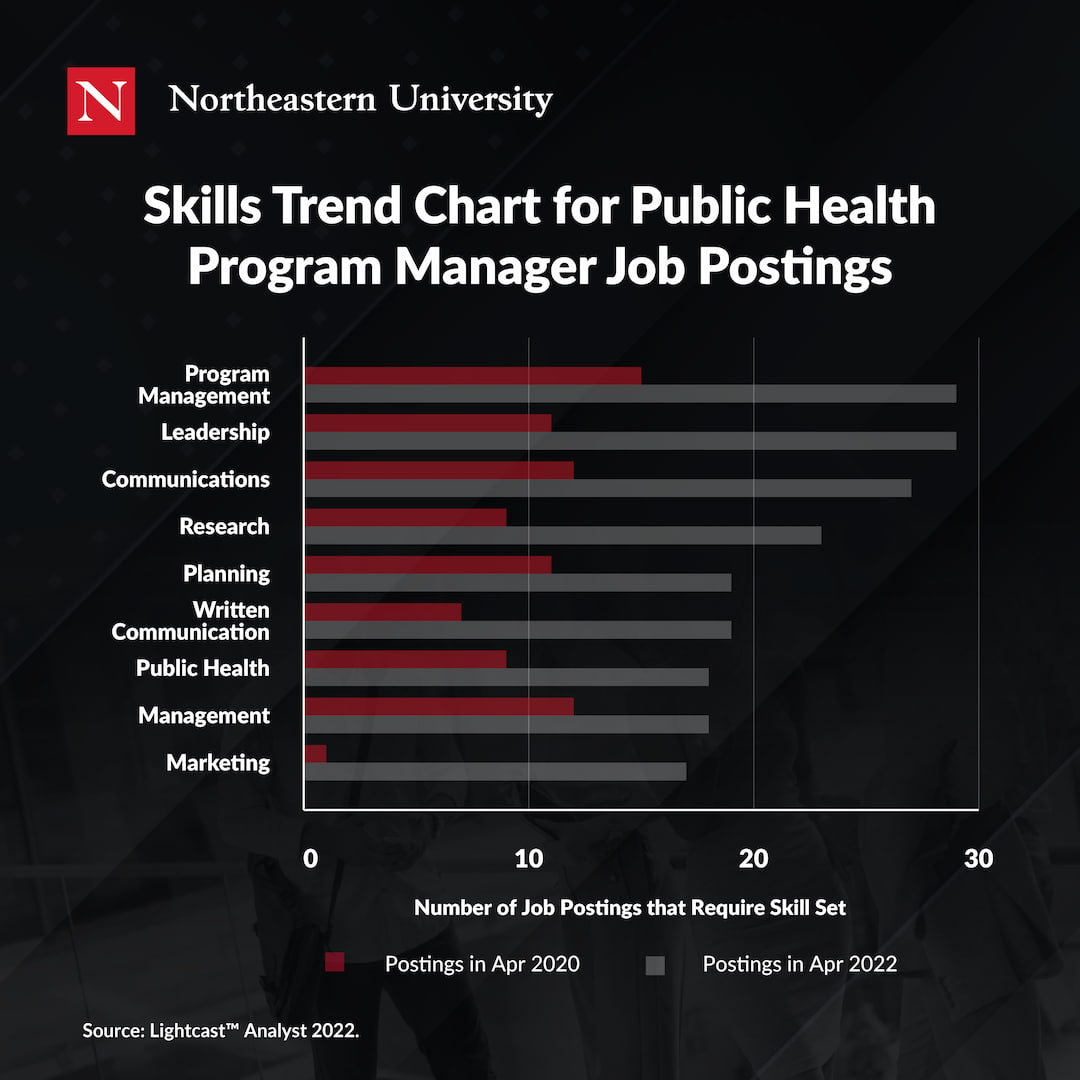

Some public health employers may refer to the core competencies to develop job descriptions in postings, performance objectives and assessment, and workforce development plans to ensure a skilled workforce . Plus, for students who are about to enter the job market, knowing the core competencies is a great way to understand your own strengths/weaknesses and evaluate your professional capabilities.

What are the 5 Core Competencies of Public Health?

A master’s in public health program, such as Master of Public Health(MPH) or Master’s in Healthcare Administration , advances a graduate student’s understanding of the following five public health disciplines.

Biostatistics

Competencies in biostatistics enable public health professionals to address and solve problems in public health by analyzing and interpreting data and applying statistical reasoning and methods.

Environmental Health Sciences

This competency focuses on how biological, physical and chemical environmental factors affect human health.

Epidemiology

Often associated with public health and public health degree programs, the epidemiology competency is the ability to study diseases and injury within populations.

Health Policy and Management

It’s the ability to use both a managerial and a policy perspective to focus on the delivery, accessibility, quality, organization and health care costs for individuals and populations.

Social and Behavioral Sciences

This competency in public health examines how behavioral, social, and cultural matters contribute to public health issues.

What are the 22 CEPH Competencies of Public Health?

Built on the conventional public health core knowledge areas (biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health policy and management, and social and behavioral sciences), as well as multisector and emerging public health areas; these CEPH competencies must be demonstrated by all graduates and are critical to the success of public health professionals.

Evidence-based approaches to public health

1. Apply epidemiological methods to the breadth of settings and situations in public health practice.

2. Select quantitative and qualitative data collection methods appropriate for a given public health context.

3. Analyze quantitative and qualitative data using biostatistics, informatics, computer-based programming and software, as appropriate.

4. Interpret the results of data analysis for public health research, policy, or practice.

Public health a n d health care systems

5. Compare the organization, structure, and function of health care, public health and regulatory systems across national and international settings.

6. Discuss how structural bias, social inequities and racism undermine health and create challenges for achieving health equity at the organizational, community and societal levels.

Planning and management to promote health

7. Assess population needs, assets and capacities that affect communities’ health.

8. Apply awareness of cultural values and practices to the design or implementation of public health policies or programs.

9. Design a population-based policy, program, project or intervention.

10. Explain the basic principles and tools of budget and resource management.

11. Select methods to evaluate public health programs.

Policy in public health

12. Discuss multiple dimensions of the policy-making process, including the roles of ethics and evidence.

13. Propose strategies to identify stakeholders and build coalitions and partnerships for influencing public health outcomes.

14. Advocate for political, social or economic policies and programs that will improve health in diverse populations.

15. Evaluate policies for their impact on public health and health equity.

16. Apply principles of leadership, governance, and management, which include creating a vision, empowering others, fostering collaboration and guiding decision making.

17. Apply negotiation and mediation skills to address organizational or community challenges.

Communication

18. Select communication strategies for different audiences and sectors.

19. Communicate audience-appropriate public health content, in writing and through oral presentation.

20. Describe the importance of cultural competence in communicating public health content.

Interprofessional practice

21. Perform effectively on interprofessional teams.

Systems thinking

22. Apply systems thinking tools to a public health issue.

While both are necessary for effective public health work, they are distinct in that core competencies of public health are the knowledge, skills and abilities needed to successfully perform “critical work functions,” whereas public health specializations are a narrow or defined area of expertise in which to apply core competencies.

There may be numerous ways to improve depending on your needs and career goals. You might consider advancing your education. Many online programs have been launched catering to students who don’t want to commute to campus, such as online MPH programs , online MHI programs , online MHA programs and more. There are also other ways to continue developing your competencies after graduation from school. Read our Resources for Continuing Professional Development in Public Health to learn more.

Information last updated in July 2020

Career Guide: Public Health

- Search for Organizations

- Prep for Your Interview - Research The Industry

- Career Sites

Core Competencies

Data analytics, policy development & program planning skills, communications, health equity, community partnership skills, management & finance, public health leadership & systems thinking.

- More Guides

The Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice has developed the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals , which are used by hundreds of health departments across the U.S. The core competencies are organized into 8 domains representing skill areas within public health:

- Data Analytics & Assessment Skills

- Communication Skills

- Health Equity Skills

- Public Health Sciences Skills

- Management & Finance Skills

- Leadership & Systems Thinking Skills

Many jobs and careers related to public health will involve using some combination of these skill domains. The MPH Career Services Program recommends students explore and identify the skill domains they are most interested in further developing and utilizing in their careers. In addition, it can also be helpful to use the skill domains as an organizing principle for one's job search and as a marketing tool.

The resources below provide a starting point for exploring opportunities within the skill domains. If you have a recommended resource to add, please contact Career Services Manager, Chandlee Bryan .

- Data for Health Impact Program Bloomberg Philanthropies, Data for Health Initiative

- Lessons in Leadership: Using Data to Drive Public Health Decisions McKinsey

- What's the Difference between a Data Analyst and a Data Scientist? Career Foundry

Python, R, and Stata are three common programming languages used in data analytics. Here are library guides to provide you with resources for learning each of them

- Python Bites Workshop Series - Research Guides at Dartmouth College

- R Koujue - Statistical Software - Research Guides at Dartmouth College

- Stata Koujue - Statistical Software - Research Guides at Dartmouth College

- Public Policy Development Public Health Institute

- National Conference of State Legislatures

- Public Health Communications Collaborative Communications resources for public health professionals

- Health Communications Strategies and Resources National Prevention Information Network

- Usability.gov

- Health Equity Assessment Tool Kit World Health Organization

- Health Equity Curricular Toolkit American Academy of Family Physicians

- Health Equity Toolkit for COVID-19 Big Cities Health Coalition and Human Impact Partners

- Rural Health Equity Toolkit RHIhub

- Sources for Data on Social Determinants of Health CDC

- Indian Health Service Community Health Tools

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)

- Public Health Toolbox

- Rural Health Data Sources & Tools Ruralhealthinfo.org

- Urban Health World Health Organization

- Public Health Finance National Association of County and City Health Officials

- Public Health Finance & Management Bootcamp

- Health Systems Governance and Financing World Health Organization

- National Leadership Academy for the Public's Health CDC - Public Health Professionals Gateway

- Center for Health Leadership and Practice Public Health Institute

- Systems Thinking Resources New England Public Health Training Center

- << Previous: Career Sites

- Next: More Guides >>

- Last Updated: Feb 8, 2024 3:47 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.dartmouth.edu/mph-career

- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2023

Developing public health competency statements and frameworks: a scoping review and thematic analysis of approaches

- Melissa MacKay 1 ,

- Caitlin Ford 1 ,

- Lauren E. Grant 1 ,

- Andrew Papadopoulos 1 &

- Jennifer E. McWhirter 1

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 2240 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1710 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Competencies ensure public health students and professionals have the necessary knowledge, skills, values, and behaviours to do their jobs effectively. Public health is a dynamic and complex field requiring robust competency statements and frameworks that are regularly renewed. Many countries have public health competencies, but there has been no evidence synthesis on how these are developed. Our research aim was to synthesize the extent and nature of the literature on approaches and best practices for competencies statement and framework development in the context of public health, including identifying the relevant literature on approaches for developing competency statements and frameworks for public health students and professionals using a scoping review; and, synthesizing and describing approaches and best practices for developing public health competency statements and frameworks using a thematic analysis of the literature identified by the scoping review. We conducted a scoping review and thematic analysis of the academic and grey literature to synthesize and describe approaches and best practices for developing public health competency statements and frameworks. A systematic search of six databases uncovered 13 articles for inclusion. To scope the literature, articles were assessed for characteristics including study aim, design, methods, key results, gaps, and future research recommendations. Most included articles were peer-reviewed journal articles, used qualitative or mixed method design, and were focused on general, rather than specialist, public health practitioners. Thematic analysis resulted in the generation of six analytical themes that describe the multi-method approaches utilized in developing competency statements and frameworks including literature reviews, expert consultation, and consensus-building. There was variability in the transparency of competency framework development, with challenges balancing foundational and discipline-specific competencies. Governance, and intersectoral and interdisciplinary competency, are needed to address complex public health issues. Understanding approaches and best practices for competency statement and framework development will support future evidence-informed iterations of public health competencies.

Peer Review reports

Competencies are defined as the knowledge, skills, values, and behaviours required to perform well within a profession and an organization [ 1 ]. Knowledge can be acquired through education and experience [ 1 ]. Skills result from the repeated application of knowledge, and behaviours reflect how individuals perform in various contexts [ 1 ]. Attitudes and values form the context in which competencies are practiced and are the beliefs that motivate people to act in different ways [ 2 ]. Competencies required for professional practice depend on many factors including an individual’s position within an organization and an organization’s needs [ 1 , 3 ]. Within education, curriculum and pedagogical approaches provide students with opportunities to advance their knowledge and skills through didactic and experiential training [ 4 , 5 ]. For both professional development and education, defining the competencies needed and creating development opportunities explicitly linked to them is essential.

There are various conceptualizations of competencies, including behavioural, performance continuum, and integrated or holistic approaches. Each conceptualization has strengths and weaknesses based on the complexity and interconnectedness of the approach, its focus on tasks or job performance, and how competencies are developed within individuals during their careers [ 6 ]. The holistic approach to competence conveys the interrelationship of knowledge, skills, behaviours, and attitudes/values [ 6 , 7 ]. Frameworks and approaches to competencies are context-dependent and developmental, where there is progressive interaction between an individual’s tasks, abilities, and the systems and environments in which they perform [ 6 ]. Thus, establishing an integrated competency framework for any discipline or sector, including public health, provides clarity and professional standards, promotes reflective practice, and requires a clear understanding of the interconnectedness of the attributes required.

Competency statements for public health ensure students and practitioners have the necessary knowledge, skills, behaviours, and values to effectively perform [ 2 , 8 ]. This promotes standardization in the field and provides a benchmark for capable personnel, allowing for a consistent approach to organizational planning and performance measurement, which in turn improves the quality of public health programs and services [ 5 ]. Competency frameworks define a set of competency statements and support their implementation through describing public health practice expectations and informing workforce planning and development [ 9 ]. There are a number of frameworks for public health competencies around the world, including the Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada [ 2 ], the United States (US) Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals [ 8 ], the WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European Region [ 10 ], the Public Health Competencies and Impact Variables for Low- and Middle-Income Countries [ 11 ], the Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health Competency Framework [ 12 ], and the Core Competencies for Public Health: A Regional Framework for the Americas [ 13 ].Although each framework consists of different conceptualizations of competencies for different countries and sociopolitical regions, they are all based on a need for a tool that facilitates development of a knowledgeable and skilled public health workforce able to effectively address complex public health challenges [ 4 ].

Current public health challenges include multiple crises including climate change [ 14 ], mental health [ 15 ], and opioid use disorder [ 16 ], which overlap many sectors and disciplines. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing global health issues including health inequities, mental health, social isolation, and addictions [ 17 , 18 ]. Additionally, declining trust in public health resulted from ineffective crisis communication and management [ 19 ], and a complex information ecosystem where mis/disinformation is widely circulating [ 20 ]. More than ever, public health needs competency frameworks that reflect the current multifaceted and overlapping public health challenges to ensure the workforce is adequately equipped to address them.

Core competency frameworks in public health are usually developed through collaboration with a range of public health experts and professionals. Public health competency frameworks are developed at various levels including the country level, organizational level, and discipline-specific public health practice to support workforce development planning, professional development, and improved public health action. For example, within Canada, the Core Competencies for Public Health were released in 2008 by the Public Health Agency of Canada in collaboration and consultation with public health practitioners, government, and experts [ 2 ]. Similarly in the US, the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals are developed and updated through extensive consultation and revision with the public health and population health sectors across the country [ 21 ]. This work also occurs on an organizational level within academia to develop programs and curriculum matched to public health competency frameworks [ 22 ], as well as for specific disciplines within public health such as implementation science [ 5 ], public health preparedness and response [ 23 ], and environmental public health [ 24 ].

The field of public health is dynamic and complex; thus, competency frameworks must be regularly updated to remain relevant. Approaches for developing public health competency statements and frameworks must be optimized and mobilized to ensure they are relevant and have impact within public health [ 25 ]. Renewal of public health competency frameworks varies globally, with some countries regularly updating their competencies, such as the US (considers renewal three years after the prior release), while others, such as Canada, do not currently have a systematic approach to updating competencies, though there are calls for renewal and efforts are underway to revisit this. Identifying and describing approaches for the development of public health competency statements and frameworks will support future evidence-informed iterations, but no previous evidence synthesis has been conducted.

To address this gap, our goal is to synthesize the extent and nature of the literature on approaches and best practices for public health competencies statement and framework development. The objectives are:

Identify relevant literature on approaches for developing competency statements and frameworks for public health students and professionals using a scoping review; and,

Synthesize and describe approaches and best practices for developing public health competency statements and frameworks using a thematic analysis of the literature identified in the scoping review.

Review approach and team

The scoping review methods were based on the framework outlined by Arskey and O’Malley [ 26 ] and updated by Levac et al. [ 27 ]. A research team with expertise in the subject matter and methods was established to develop and guide the scoping review protocol and thematic analysis [ 26 , 27 ]. A specialist research librarian with expertise in public health and research synthesis was consulted for the scoping review protocol. This scoping review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews [ 28 ].

Review scope

Articles were included if they were published in English. There were no geographic or date restrictions. Peer-reviewed journal articles with qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed methods study designs, dissertations, and grey literature were included. Literature was included when it focused on developing competency statements and frameworks for public health students and practitioners. Competency development in other disciplines (e.g., medicine, dentistry, etc.) was excluded unless it was explicitly public health focused (e.g., public health nursing).

Search strategy

In collaboration with the research team and a specialist research librarian, the search strategy was developed by exploring the relevant literature for keywords and controlled vocabulary. Originally, our review intended to focus on communication-related competencies for public health specifically, so controlled vocabulary and keywords were included to reflect this focus. During the screening process, it became apparent there was not enough literature focused on public health communication. The search strategy was expanded to focus across all competencies relevant to public health, including communication.

The search strategy was tested in Ovid via MEDLINE and refined to ensure the results were relevant to the review scope. The search strategy was then translated for use in other databases by modifying syntax, as needed. The final search was carried out on November 24, 2022, in the following databases: Ovid via MEDLINE (Table 1 ), PsycINFO, Web of Science, Communication and Mass Media Complete, ERIC, and CAB Direct. These databases were selected to provide a comprehensive coverage of public health, education, and communication sources.

To supplement the database search, we hand-searched the following journals: Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, American Journal of Public Health, Journal of Health Communication, Health Promotion Practice , and Health Communication . The journals were identified by examining the most frequently cited journals in the database search results. Additional peer-reviewed articles were also identified during the grey literature search. Grey literature was searched using Google through appropriate combinations of concepts (e.g., “core competencies” AND “public health”) and pages 1–10 were screened for relevant results.

Relevance screening

The results of the search were imported into DistillerSR review software [ 29 ] to facilitate screening by independent reviewers and track all steps. Deduplication of results occurred in DistillerSR after all relevant citations were imported from Mendeley [ 30 ]. Title and abstract, and full-text screening were also conducted in DistillerSR. Reviewers (MM and CF) pilot tested ten random articles to ensure understanding of the inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers (MM and CF) screened the title and abstract of each article using a screening form and any conflicts were resolved through discussion. Kappa was 0.81 for title and abstract screening, indicating high agreement [ 31 ].

The full text of articles deemed potentially relevant during the title and abstract screening were obtained and screened independently by the same two reviewers. Steps were taken to obtain the full text of all articles including searching within the University of Guelph Library, using Google and Google Scholar, and contacting the author directly through ResearchGate or their publicly available institutional email. A screening form was developed in collaboration with the research team and pre-tested before implementation. The form assessed each article’s eligibility for inclusion in the review by the following criteria: literature type, language, population, and measurement, evaluation, or detailed report of competency statement or framework development in public health students and/or the workforce. After completion of full-text screening, Kappa was 0.80, indicating high agreement [ 31 ]. Conflicts were resolved through discussion to the point of reaching agreement for inclusion or exclusion in the review.

Data extraction

Two researchers conducted data extraction for the included articles (MM and CF). Each researcher acted as the primary data extractor for half of the dataset and validated the other half as the secondary data extractor. Key information was extracted using an Excel form developed in collaboration with the research team [ 32 ]. The following information was extracted from each included article: title, author(s), year, article type, country of origin, study design, study aim, methods, theories or frameworks included, institutions involved in developing competency statements, existing competency frameworks included, focus of competency framework (e.g., general or discipline-specific), process used to develop competency statements or framework, level of competency development focus (e.g., nation-wide, organizational, etc.), target population (e.g., graduate student, general public health practitioner), transparency of the process, lessons learned, implementing and adoption of competency statements or framework, evaluation of the process, bias identified, and future research directions.

The results of the data extraction were thematically analyzed following the method outlined by Arskey and O’Malley [ 26 ] and updated by Levac et al. [ 27 ]. First, the research team developed key areas to capture results for data extraction to answer objective 2, including transparency of methods and results, evaluation of the process, lessons learned, and implementation/adoption of the competencies. One researcher (MM) coded the extracted data line-by-line, as well as revisited the full text articles, to develop an initial thematic framework that described approaches and best practices for developing competency frameworks in public health. Codes were inductively created based on the key areas of data extraction outlined above and refined into larger concepts where data overlapped to generate initial themes. Significant outliers were captured in the coding and incorporated into themes where appropriate. Approaches for developing competency statements and frameworks described any methods undertaken and/or key recommendations for generating competency statements for public health that outline the values, knowledge, skills, and behaviours needed to effectively perform in various public health roles. Best practices describe areas of significant overlap in the data that reported successful methods or recommendations for developing, implementing, and/or evaluating competency statements and frameworks for public health. The research team collaboratively discussed and refined the themes to provide perspective and triangulation of results, ultimately developing six analytical themes. The research team also identified any areas of ambiguity during discussion and/or revisions and MM revisited the extracted and coded data, as well as full text articles, to add detail. The research team then collaboratively discussed, refined, and finalized the analytical thematic framework.

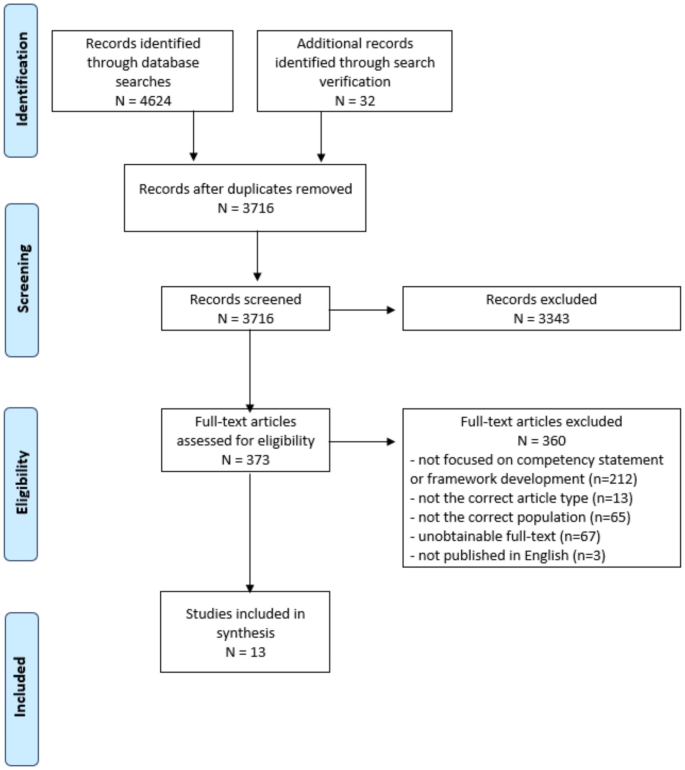

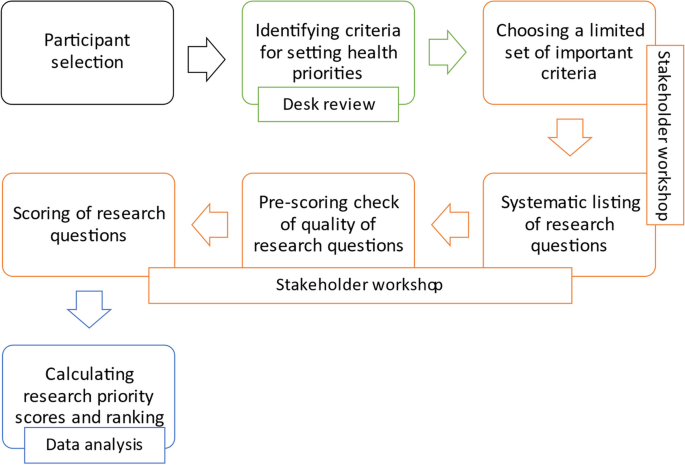

Search and selection of articles

A total of 3,716 articles were screened at the title and abstract stage following deduplication. Next, 373 full-text articles were reviewed for relevance, with 13 studies identified for inclusion. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flow diagram of the article screening and inclusion process.

PRISMA flow diagram of scoping review process

Characterization of Articles included

Most included articles were peer-reviewed journal articles, used qualitative or mixed method design, and were targeted towards generalist public health practitioners (Table 2 ). See Supplementary Table 1 for the data extraction results.

Thematic analysis

Six themes were generated to describe the approaches and best practices for developing competency statements and frameworks for public health. The themes related to the approaches include initial methods used, building consensus, and transparency in reporting. Themes related to best practices include governance and coordination and a multifaceted approach for addressing complex public health challenges. The theme describing developing foundational and discipline-specific competencies and those that apply to varying levels of expertise included approaches and best practices.

Initial competency statements are developed using literature reviews and expert consultations

Literature reviews [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ], expert consultation [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ], or a combination of both [ 35 , 36 , 42 , 43 ] were used to develop initial competency statements.

As a first step, a literature review was often completed to identify competencies, including for public health physicians [ 43 ], health communicators [ 42 ], global public health practitioners [ 35 ], and for health literacy for public health professionals [ 34 ]. Grey literature, including existing country-level public health competencies (e.g., USA, Europe, Canada, New Zealand, Spain), existing competency frameworks (e.g., Emergency Preparedness Core Competencies for Public Health Workers), textbooks, and public health education curricula was frequently included in literature reviews for competency list development [ 33 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 43 ]. Less frequently, expert consultation was used as a first step in developing competency statements, including for emergency preparedness and response [ 37 ], public health epidemiology [ 44 ], and for senior public health officials [ 39 ]. Additional methods for getting started included conducting an environmental scan, which was used to develop Indigenous public health core competencies [ 36 ].

As a second step, expert consultations took place using interviews and surveys to gather information relevant to competency framework development, including feedback on competency statements, contextual factors, and responsibilities of and gaps in the workforce, including at various levels of public health practice [ 42 , 43 ] and within academia [ 35 ]. Exemplar practitioners who demonstrate the competencies within well-established practices can model the knowledge, skills, and abilities required within a particular context [ 40 , 41 ]; however, expert consultations are not an appropriate first step when the area of practice is emerging and there is no history of exemplar practitioners [ 34 , 40 ]. Representation is important for expert consultations: Indigenous peoples’ leadership in creating an Indigenous competency framework ensured their beliefs, values, and knowledge were central [ 36 ]. Context, including culture, geography, experience, and education must be considered when identifying evidence and theory for competency list development [ 37 ].

While some of the included literature identified potential challenges in gathering and synthesizing diverse expert opinions within their methods [ 34 , 36 , 39 , 41 ], no insights on how these were addressed during the research were shared in the results or discussion. One exception was that participants of a consensus-building process with less expertise had some difficulty understanding more complex competencies [ 41 ]. The authors did not elaborate on how this may have impacted the results or how they addressed this issue during the research, other than recommending that further research in this area is needed.

Public health competency statement development is consensus-driven with practitioners and researchers

Expert consultation and validation by experts and practitioners must be included to increase the impact of competency frameworks [ 34 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Expert consultation that provides repeated assessment of the competency statements increases the validity of the results [ 43 ], convergence of findings [ 34 , 39 , 44 ], and comprehensiveness of the framework [ 41 ]. Modified Delphi technique was frequently used to facilitate discussion between experts and allow for successive feedback of the group opinion on competency statements [ 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 ]. For example, a Delphi technique to build competencies for bioterrorism and emergency readiness in public health gathered experts from food safety, epidemiology, occupational health, and Indigenous health and included various levels of expertise and roles, including Directors, staff, and community leaders [ 37 ].

Other techniques to develop consensus on competency frameworks included focus groups [ 37 , 41 ], workshops [ 44 , 45 ], a survey [ 42 , 43 ], interviews with expert practitioners [ 43 ], an advisory committee [ 33 ], and a conference with experts [ 38 ]. The size of the consensus-building expert group should reflect the uncertainty in the literature, resources available, and the topic area within public health [ 34 ]. For example, an expert panel for developing health literacy competencies aimed to include at least 20 individuals from across a network of schools of health professionals, educators, and experts in health literacy to attend an in-person two-day meeting to ensure a variety and breadth of perspectives included [ 34 ].

Purposive sampling of experts to gather various levels of experience and expertise within various public health disciplines was frequently used [ 34 , 37 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Participants were recruited via professional association listservs [ 34 , 42 , 44 ], relevant government and community-based organizations [ 37 ], and public health agencies [ 41 ]. In terms of number of participants, studies did not include any information on a priori sample sizes for quantitative methods, however, qualitative methods were guided by the achievement of data saturation [ 41 , 44 ].

As part of the consensus-building process, surveys are often used to gather feedback on agreement [ 34 , 37 , 42 , 44 ] and importance [ 34 , 35 , 37 , 40 , 42 ] of competencies. Likert scales were used, including a 4-point scale of importance ranging from 1 (very important) to 4 (not important) [ 34 ], a 5-point scale of importance ranging from 0 (not used at all) to 4 (essential) [ 42 ], and a 5-point agreement scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [ 44 ]. Competency statement acceptance, rejection, or clarification based on feedback through surveys were sometimes reported [ 34 , 44 ].

Transparency of consensus-building processes for developing competency frameworks varied

Reporting transparency regarding how consensus on competency frameworks was reached varied. Some studies were very detailed [ 34 , 39 , 41 , 42 ] while others less so [ 35 , 38 , 45 ].

Studies often reported response rates and agreement for all competency items included [ 34 , 35 , 39 , 44 ]. Statistical analysis, usually as associations between agreement ratings, and agreement levels for included competency statements, were also reported [ 39 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Statistical analysis included a factor analysis to reduce and synthesize the overall number of behavioural traits identified for public health physicians [ 43 ], means and standard deviations to identify participant characteristics and the importance of the competence statements [ 42 ], and bivariate analyses to determine if the level of agreement differed by participant characteristics [ 44 ]. A pre-determined threshold of acceptance was used by Coleman et al. [ 34 ] to increase the validity of findings.

Overall results of the process to build consensus on a final competency framework were reported by some studies but details were often lacking on how agreement was assessed [ 33 , 37 ].

Competency frameworks varied across foundational and discipline-specific competencies and levels of expertise

Competency frameworks must balance comprehensiveness with being targeted to various disciplines and roles within public health [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 45 ]. While specialist competency frameworks are necessary, a coherent and unifying public health competency framework is needed to provide structure, guidance, and a common understanding of public health more broadly [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 45 ]. There is overlap between competency skills, knowledge, and behaviours within competency domains and between foundational and discipline-specific frameworks [ 25 , 46 ], making it more difficult to assess agreement or importance during consensus-building [ 34 , 44 ].

Foundational competencies to address systemic factors related to colonialism and incorporate non-Western knowledge and Indigenous governance structures in public health are also necessary [ 36 ]. For example, community health workers are excluded from needing to have all the core competencies in the Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada 1.0 release [ 36 ]. However, these public health practitioners play a central role in Indigenous health and lack of proficiency in all the competencies can significantly impact Ingenious health [ 36 ].

Discipline-specific competencies define the roles within public health and guide professional development and education within the specialty [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. In discipline-specific areas, such as emergency preparedness and response, competency development must reflect all potential public health areas of action and interdisciplinary and intersectoral action [ 37 , 40 ]. Working collaboratively across sectors, disciplines, and at different levels of service enhances the impact of public health action and must be reflected in competencies for public health in discipline specific frameworks [ 38 ], as well as foundational frameworks.

Coordination across levels of jurisdiction, as well as credentialing practitioners from novice to expert levels of competence, facilitates integration of competencies into practice [ 37 ]. A model for lifelong learning for bioterrorism and emergency management is used to credential practitioners at varying levels of expertise from novice to expert, which combines education, practical experience, and learning outcomes to assess the level of expertise [ 37 ]. Similarly, competencies for public health can be approached at various levels of expertise including basic, advanced, and expert [ 37 , 39 , 41 ]. For example, verb changes can be made to competency statements to make them more appropriate for varying levels of expertise (e.g., understand vs. analyze vs. create) [ 41 ]. Competency theory can be used in combination with a foundational approach to create competency frameworks for public health where statements are interpreted for different functions in public health (e.g., communication, leadership, policy) [ 41 ].

Recognition and integration of competence acquired through experience, professional development, and strategic development toward organizational goals must be recognized, along with those acquired through formal education [ 37 , 41 , 44 ] and different forms of knowledge, including Indigenous ways of knowing [ 36 ]. Bhandari et al. [ 39 ] also note the distinction between competencies for public health students -- those that are expected to be obtained by the end of the education program and organized around academic disciplines – and professional competencies which reflect the needs of the workforce. The two are intricately related as professional competencies, or those needed to effectively perform on the job, should guide and inform educational competencies [ 39 ].

Governance ensures competency frameworks are current, integrated into practice, and connected to professional development

Funding to establish indicators or performance measures for competencies to ensure their integration into practice is needed [ 38 , 45 ]. Professional development in the competency areas is necessary for integration into practice and requires dedicated, ongoing funding [ 38 , 45 ]. Common methods of competency assessment should be a key area of governance and funded programming within professional development [ 41 ]. Quality assurance mechanisms for professional development are needed that reflect the local context and should be implemented by training organizations and institutions [ 38 ]. Ideally, an independent administrative body should be instituted to develop and implement standards and quality assurance mechanisms [ 38 ].

Competency lists must be revisited and revitalized on a consistent basis in partnership with various sectors such as healthcare and academia [ 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Discipline-specific competency frameworks must be reviewed and updated more regularly compared to general frameworks [ 40 ]. Competency frameworks that have not been updated for five years or more should be used with caution, especially in curriculum design, health communication, and organizational planning [ 40 ]. Overall, renewal should be planned for as part of the overall initial development of any framework and should include a survey of current practices to understand strengths and areas of opportunity [ 40 ].

A comprehensive plan for communicating the results of developing competency frameworks ensures competencies are adopted by public health organizations [ 38 ] and the work is not duplicated [ 40 ]. Various formats for competency frameworks were used, including Tables (33,34,39,42,43), lists [ 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 ], visual models [ 36 , 43 , 45 ], and concept maps [ 44 ]. Only one study included any evaluation of the usefulness of the design and found simple and concise layouts were preferred [ 41 ].

Competency frameworks provide organizations and policymakers with a tool by which they can address their specific context and needs through workforce planning, including developing job descriptions, performance indicators, and professional development opportunities [ 39 , 40 ]. New and revitalized frameworks should be mapped against job descriptions in public health to identify gaps [ 39 ]. Practitioners were apprehensive around competency frameworks being used for accreditation and performance evaluation [ 44 ]. Training programs should be designed and assessed to ensure they are able to develop the competencies that are outlined within frameworks [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Professional development for the current public health workforce must be integrated within the development and implementation of public health competency frameworks [ 34 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 ].

Values underpin and support competency frameworks to enable public health to address complex public health challenges

Values should be reflected in competency statements, although these are the most difficult to develop and measure [ 36 , 38 , 43 ]. A reflexive practice to identify the values and beliefs that guide public health practice would contribute to intercultural competency [ 36 ]. Values must include a commitment to health equity, social justice, intercultural competency, climate justice, and others that are rooted in the social ecological model of health and the social determinants of health [ 35 , 36 , 38 , 42 ].

Although many frameworks highlight the importance of reducing health inequities (e.g., in the preamble), they varied in terms of the emphasis placed within competency statements on reducing health inequities and culturally appropriate approaches to public health [ 36 , 39 ]. Competencies for providing culturally appropriate public health and healthcare for Indigenous peoples are vital and can contribute to overcoming misunderstanding, discrimination, and racism [ 36 ]. The explicit recognition of Indigenous peoples, colonialism and the impact on health, and related health inequities throughout the public health core competencies, including integration within definitions in the glossary and practice examples, is necessary [ 36 ].

Public health competencies are necessary to facilitate shared understanding of expectations and actions required to address complex public health issues that are intersectoral and interdisciplinary [ 38 , 41 , 45 ]. The ability to influence policy and develop partnerships can be negatively influenced by predominant culture and requires political will and in some cases governmental reform to ensure competencies to address complex public health issues are included in public health frameworks and practice [ 36 , 38 , 41 , 43 ]. A flexible, action-oriented, and regulated public health workforce is needed to address serious and complex public health challenges, including climate change and health inequities [ 45 ]. Greater integration of competency frameworks with relevant legislation, programs, and guidelines for the specific jurisdiction, as well as within global health, to address complex public health issues is recommended [ 44 ].

Overall, thirteen articles were identified related to approaches for developing competency statements and frameworks for public health, just one of which focused on communication competence. Most of the included literature was original, peer-reviewed research using qualitative or mixed-methods approaches. The main target population for competency framework development was generalist public health practitioners and the process was largely driven by academia. Foundational competency frameworks for general public health practice at the country level were the most commonly developed in the included studies. A range of approaches, especially in combination, were taken for developing competency statements frameworks, with consensus-building through modified Delphi techniques, expert consultation, and surveys commonly used. Below, we summarize the six themes described in the results and discuss these approaches and their importance for developing public health competency statements and frameworks (Table 3 ). In Table 3 , the content within the Actions to Achieve Recommendation column summarizes key aspects of the results and discussion that relate to the success and impact of the approaches and best practices for developing competency statements and frameworks identified. We compare and contrast our findings to similar literature in veterinary medicine and healthcare to put the recommendations into a wider context and body of knowledge.

A strong evidence-informed foundation for developing competency statements bridges the research-practice interface. The quality of the evidence used to generate findings is key to the reliability and validity of the resulting competency frameworks [ 47 , 48 ]. Literature reviews, expert consultations, review of existing competency frameworks, and environmental scans can be used as a first step to gather evidence [ 48 , 49 ] that can close the gap between research and practical knowledge and provides contextual evidence about the public health system in Canada. Within healthcare, a similar process is used where literature reviews [ 50 ], surveys [ 51 ], and interviews [ 52 ] were used to develop the initial list of competency statements for further consensus-building [ 49 ]. This approach is consistent with the steps outlined in the Delphi and modified Delphi techniques [ 48 , 49 ].

Multi-step processes for consensus-building, including expert consultation and iterative methods, increase the validity of results through the incorporation expert knowledge and research findings [ 49 ]. Expert consultation is a key step in the consensus-building process to ensure a strong basis in the evidence [ 47 , 48 ]. Practitioners and researchers are most often included in consensus-building processes in the included public health literature and within healthcare [ 50 , 51 , 52 ] and veterinary medicine [ 53 , 54 ]. Consensus-building processes to develop competency frameworks in the included literature were most often academia-led and conducted via expert consultations, surveys, and modified Delphi technique with public health academics and practitioners. However, public health goes beyond the public health sector and the consensus-building process should include community-based organizations, government, and other stakeholders to ensure community needs and values are being met [ 45 ]. The inclusion of other actors ensures competencies are reflective of collaborative, intersectoral, community-based public action.

Transparent and comprehensive reporting of the methods and results of consensus-building processes for public health competencies and frameworks is needed so that the research can be repeated, or similar processes can be implemented, and understood. The details of the consensus-building process were lacking in some studies – a similar trend has found for competency framework development in the healthcare [ 50 , 51 , 52 ] and veterinary medicine [ 53 , 54 ]. This is also true across health research in general where lack of transparent reporting makes interpreting the methods, evaluating the reliability and validity of results, and comparing to the wider body of knowledge difficult [ 55 ]. Research with low transparency has implications for use including possible harms and unintended consequences and reducing the possibility of benefits, contributing to lower overall public health impact [ 56 ]. Competency theory and validated instruments that guide consensus-building and ensure reliable and accurate results were identified as lacking by included studies. A threshold for agreement has also not been validated, making it difficult for studies to select an a priori level of agreement [ 34 , 39 ]. The focus on validated instruments within competency framework research tends to be for measuring perceived competence development in education [ 57 ] or professional development [ 58 ] rather than the process itself of developing consensus when building competency frameworks. Pilot testing of instruments for measuring agreement during consensus-building can help to ensure validity before the process begins. The CONFRED-HP (COmpeteNcy FramEwork Development in health professions) recommendations for reporting provides researchers with clear descriptions of vital areas for reporting the development of competency frameworks to increase the transparency and trustworthiness of the research and allow for informed decision-making around its use [ 59 ]. The EQUATOR (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency Of health Research) Network guidelines can be used for increasing the transparency and trustworthiness of research on building competencies in public health students and practitioners [ 55 ]. Reporting guidelines are important tools that support best practices in research reporting, contributing to increased transparency and research impact [ 56 ].

Public health effectiveness relies on how practitioners combine their individual values, knowledge, skills, and behaviours to address community needs. The effectiveness of a public health team and workforce results from this combination across individuals, levels, and disciplines [ 60 ], although interdisciplinary teamwork is difficult [ 61 ]. Foundational competencies lay the groundwork for a common understanding of what is required to do good work in public health. Discipline-specific competencies allow for public health practitioners to have opportunities to learn and build on foundational competencies for additional mastery [ 62 ]. Despite this, diversity of competency frameworks and levels of competencies (expert and foundational vs. specialized) are key challenges in developing competency frameworks [ 63 ]. The diversity in competencies and the subsequent difficulties have implications for workforce planning and development and education [ 63 ]. Frameworks that combine different ways of knowing, including theory and practice-based knowledge, and practical examples can help contextualize the competencies [ 63 ] to different expertise levels and specializations within public health. Competencies related to communication and interdisciplinarity can assist with the challenges of multiple levels of expertise and foundational and discipline-specific competencies as well [ 25 , 60 , 64 ].

Integrating competency frameworks into practice requires governance and coordinated efforts, as identified by the included literature. Governance of public health core competencies is necessary to ensure competency frameworks are up-to-date, appropriately resourced, and reflective of current public health needs and values. Within a governance structure, funding, standards and quality assurance, and a comprehensive framework rollout plan were also identified as necessary. A lack of resources and infrastructure to support the development, implementation, evaluation, and ongoing refresh of competencies are key contextual factors influencing the success of competency frameworks [ 46 ]. This complements findings from another review indicating that a comprehensive and coordinated implementation strategy, including resources, governance, and collaboration, is associated with the use and impact of competency frameworks [ 25 ].

Design and readability of competency frameworks impacts their use and effectiveness. Competency statements should be written in clear language and be reasonable in number, and frameworks should be user-friendly, use tables, and be translated where applicable [ 25 , 65 , 66 , 67 ]. Although there were a range of presentations in the included literature, most did not evaluate the usefulness of the design, with the exception of Shickle et al. [ 41 ], which found clear language was preferred.

Finally, a multifaceted approach to developing and measuring competencies is needed to address complex public health challenges. Complex public health issues including climate change, global health, health inequities, and racism/discrimination must be addressed, reflected, and integrated into public health competencies. Values that guide our research, practice, and community interactions must also be reflected in competency statements and frameworks to address these complex issues. Values are most often geared at individual practitioners but should also be extended to organizational values, as these create a culture and context for individual values to guide practice [ 68 ]. In the context of Indigenous health and reconciliation, it is imperative to explicitly integrate decolonization, anti-racist, and culturally appropriate public health practice into the public health competencies [ 36 ]. Within other disciplines, including midwifery [ 69 ] and healthcare [ 70 ], core competencies have been proposed to guide providers working to address health disparities and ensure culturally safe and effective services for Indigenous Peoples. Structural factors, including power dynamics, current and historical relationships, and needs and resources of marginalized groups must be incorporated into competency frameworks and directly influence use [ 25 , 46 ]. Competency frameworks should be flexible enough to serve as practice guidelines that can be adapted to suit the specific context, complexity, and population requirements in which it is being applied [ 25 ].

Limitations

Within the current study, the results could be limited by the selection of databases; however, we used a number of diverse databases and supplemented the search by hand searching and grey literature. Further, our research intended to focus on health communication, but found the literature to be greatly lacking, rendering a more focused review impossible. The inclusion of health communication as a key concept within the search strategy may have limited the results to those public health competency frameworks that included communication. Communication is identified across many disciplines, including public health, as a key competency, so this aspect may not have had a great impact on the results. The results may also be limited by language bias as studies were only included if they were published in English. Although we had no date or geographic restrictions, this language bias may have limited articles globally, especially those that are low or low-middle income countries, impacting the overall generalizability of results.

Biases created by study design of the included articles also result in limitations, including participant recruitment and the methods used to understand their perspectives. Information bias was present as most studies employ purposive sampling to select consensus-building groups [ 34 , 35 , 37 , 41 , 44 ]. There is also no established target number of participants for consensus-building processes for developing competency frameworks (Coleman et al., 2013) and sample sizes can be small [ 35 , 41 , 42 ]. The nature of participant experience and breadth of perspective could also be limited by the sampling [ 34 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 ]. Further, many studies relied on expert knowledge and the literature to develop competency frameworks, but many areas of public health are rapidly expanding and changing [ 34 ] and/or lack the theoretical underpinning necessary to ensure reliable and valid results [ 34 , 39 , 41 ]. Some studies reported an a priori cut-off point for agreement [ 34 , 39 ]; however, this threshold is not validated in the research [ 34 , 39 ].

Future research directions

Research is needed to distinguish between competencies required for core public health roles versus those for specialized roles. Research specific to the various disciplines, including public health communication, is needed to determine best practices for developing, implementing, and evaluating competency frameworks. Research reporting on the implementation and evaluation of foundational and discipline-specific competency frameworks is needed to help understand best practices and challenges in harmonizing varying competency frameworks in practice. The creation and implementation, reliability, and validity of a competency assessment instrument should also be explored. Some areas of literature related to competency statements and frameworks, such as health literacy, are heavily skewed towards healthcare and medicine, and more work is needed centring different topics within public health so that the focus is at the population level rather than the patient/individual level. Research to strengthen the connection between competency frameworks and the learning outcomes of public health graduate training and professional development would be valuable. Finally, research is needed to evaluate consensus-building processes from the perspective of participants and the utility and impact of the final framework, including design considerations. Literature in this area is largely focused on competency framework development and not on the evaluation of the process of development, implementation, use, or impact of the frameworks in practice.

The review scopes and analyzes the literature on developing competency statements and frameworks for public health. The findings highlight the similarities in approaches for developing competency statements and frameworks across studies, including using a multi-step process that involves literature reviews, expert consultations, and consensus-building. Foundational and discipline-specific competency frameworks, as well those that are role- and expertise-specific, including for students, new practitioners, and leaders, are needed. Variation in transparency of reporting the process of developing competency statements and frameworks exists, with some studies including very detailed methods and results while others only high-level overviews. High transparency and multi-step processes are necessary to ensure the validity, reliability, and utility of competency statements and frameworks. Governance and comprehensive plans for implementation and renewal are necessary to ensure integration of competencies into professional standards and professional development. Values that reflect culture and social justice when addressing complex public health needs must be integrated into public health competency statements and frameworks.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

National Institutes of Health. Office of Human Resources. 2017 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. What are competencies? Available from: https://hr.nih.gov/about/faq/working-nih/competencies/what-are-competencies .

Public Health Agency of Canada. Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada. Government of Canada [Internet]. Government of Canada. 2008. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/public-health-practice/skills-online/core-competencies-public-health-canada/cc-manual-eng090407.pdf .

Public Health Association of BC. Public Health Core Competency Development [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://phabc.org/public-health-core-competency-development/ .

Hunter MB, Ogunlayi F, Middleton J, Squires N. Strengthening capacity through competency-based education and training to deliver the essential public health functions: reflection on roadmap to build public health workforce. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(3):e011310.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schultes MT, Aijaz M, Klug J, Fixsen DL. Competences for implementation science: what trainees need to learn and where they learn it. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(1):19–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Belita E. Development and Psychometric Assessment of the Evidence-Informed Decision-Making Competence Measure for Public Health Nursing [Internet]. [Hamilton, Ontario, Canada]: McMaster University; 2020. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11375/25765 .

Cheetham G, Chivers G. The reflective (and competent) practitioner: a model of professional competence which seeks to harmonise the reflective practitioner and competence-based approaches. J Eur Industrial Train. 1998;22(7):267–76.

Article Google Scholar

Public Health Foundation. PHF. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals: Domains. Available from: https://www.phf.org/programs/corecompetencies/Pages/Core_Competencies_Domains.aspx .

Batt A, Williams B, Rich J, Tavares W. A Six-Step Model for Developing Competency Frameworks in the Healthcare Professions. Frontiers in Medicine [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 May 4];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/ https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.789828 .

World Health Organization. WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European Region [Internet], Copenhagen. Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/444576/WHO-ASPHER-Public-Health-Workforce-Europe-eng.pdf .

Zwanikken PA, Alexander L, Huong NT, Qian X, Valladares LM, Mohamed NA, et al. Validation of public health competencies and impact variables for low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):55.

Karunathilake IM, Liyanage CK. Accreditation of Public Health Education in the Asia-Pacific Region. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(1):38–44.

Pan American Health Organization. Pan American Health Organization. 2013 [cited 2023 Oct 23]. Core Competencies for Public Health: A Regional Framework for the Americas - PAHO/WHO. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/core-competencies-public-health-regional-framework-americas .

World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 23]. Climate change. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health .

Kuehn BM. WHO: Pandemic sparked a push for global Mental Health Transformation. JAMA. 2022;328(1):5–7.

Americas TLRH. Opioid crisis: addiction, overprescription, and insufficient primary prevention. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Oct 23];23. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(23)00131-X/fulltext .

Canada PHA. of. aem. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 3]. From risk to resilience: An equity approach to COVID-19 – The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html?utm_source=Canadian+Public+Health+Assocation&utm_campaign=cedbc06deb-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_10_30_02_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_1f88f45ba0-cedbc06deb-181652396 .

Health TLP. COVID-19 pandemic: what’s next for public health? The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(5):e391.

Leslie J, Council on Foreign Relations. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 23]. The Crisis of Trust in Public Health | Think Global Health. Available from: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/crisis-trust-public-health .

Illari L, Restrepo NJ, Johnson NF. Rise of post-pandemic resilience across the distrust ecosystem. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):15640.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Public Health Foundation. PHF. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. 2021 Revision of the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals. Available from: http://www.phf.org/programs/corecompetencies/Pages/2021_Revision_of_the_Core_Competencies_for_Public_Health_Professionals.aspx .

Calhoun JG, Ramiah K, Weist EM, Shortell SM. Development of a core competency model for the Master of Public Health Degree. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1598–607.

Ablah E, Elizabeth McGean Weist MA, John E, McElligott MPH, Laura A, Biesiadecki M, Audrey R, Gotsch D, William Keck C. Public health preparedness and response competency model methodology. Am J Disaster Med. 2013;8(1):49–56.

Wallar LE, McEwen SA, Sargeant JM, Mercer NJ, Papadopoulos A. Prioritizing professional competencies in environmental public health: a best–worst scaling experiment. Environ Health Rev. 2018;61(2):50–63.

Lebrun-Pare F, Malai D, Gervais MJ. Advisory on the Use of Competency Frameworks in Public Health: Literature Review, Exploratory Interviews and Courses of Action [Internet]. Quebec: INSPQ Center for Expertise and Reference in Public Health; 2021. Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2827 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

DistillerSR [Internet], Ottawa C. 2023. Available from: https://www.distillersr.com/ .

Mendeley. Mendeley Reference Manager [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.mendeley.com/reference-management/reference-manager .

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–82.

Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://office.microsoft.com/excel .

Baseman JG, Marsden-Haug N, Holt VL, Stergachis A, Goldoft M, Gale JL. Epidemiology Competency Development and Application To Training for Local and Regional Public Health Practitioners. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1suppl):44–52.

Coleman CA, Hudson S, Maine LL. Health Literacy Practices and Educational Competencies for Health professionals: a Consensus Study. J Health Communication. 2013;18(sup1):82–102.

Hagopian A, Spigner C, Gorstein JL, Mercer MA, Pfeiffer J, Frey S, et al. Developing competencies for a Graduate School Curriculum in International Health. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(3):408–14.

Hunt S, Review of Core Competencies for Public Health. An Aboriginal Public Health Perspective [Internet]. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal health; 2015. Available from: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/context/RPT-CoreCompentenciesHealth-Hunt-EN.pdf .

Olson D, Hoeppner M, Larson S, Ehrenberg A, Leitheiser AT. Lifelong Learning for Public Health Practice Education: a Model Curriculum for Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(2suppl):53–64.

Allegrante JP, Barry MM, Airhihenbuwa CO, Auld ME, Collins JL, Lamarre MC et al. Domains of Core Competency, Standards, and Quality Assurance for Building Global Capacity in Health Promotion: The Galway Consensus Conference Statement. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(3):476–82.

Bhandari S, Wahl B, Bennett S, Engineer CY, Pandey P, Peters DH. Identifying core competencies for practicing public health professionals: results from a Delphi exercise in Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1737.

Gebbie KM. Competency-To-Curriculm Toolkit [Internet]. Columbia University School of Nursing and Association for Prevention Teaching and Research; 2008 Mar. Available from: https://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Documents/Competency_to_Curriculum_Toolkit08.pdf .