Racial Injustice in America: Where Are We Now?

Are we moving in the right direction.

Posted October 12, 2021 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- A review of American systems suggests that racism persists in society, despite the refusal of some to acknowledge it.

- Many argue that the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor raised American consciousness regarding racial injustice.

- While there have been some measures taken toward improving race relations, changes continue to fall short.

- It is clear that Americans, from all backgrounds, need education about racial inequality, or we are doomed to continue to repeat the cycle.

By Douglas E. Lewis, Jr., Psy.D., on behalf of the Atlanta Behavioral Health Advocates

Alfred Adler, a psychiatrist known as the father of individual psychology, developed the use of Early Recollections (ERs) as a technique for psychotherapy . Adler believed that ERs, a small collection of an individual’s memories occurring before age 10, were a projection of an individual’s present-day thought or behavioral patterns on the past. The psychotherapist and the individual discuss these ERs, and through collaborative interpretation acquire a deeper understanding of the individual’s personality and behavioral functioning.

My earliest memory is when I visited the local health department for my “shots” or vaccinations. I could not have been older than three years old. I recall a White American child, presumably my same age, kindly sharing his Cheerios with me. My dad noticed the exchange after I ate a handful, and he forcefully told me to stop! What I now recognize is that my dad did not only seem annoyed by my apparent disobedience or social infraction, but he also seemed fearful or concerned. Immediately following his command for me to stop, the other child’s mom reassured my dad that it was “okay” for me to have some Cheerios. It has been three decades since that experience, and it remains etched in my memory.

The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor last year appeared to raise American consciousness about the impact of race in a way not previously observed. The American Congress put forth the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, “Juneteenth” was declared a paid federal holiday, and Corporate America as well as institutions of higher learning put in place a number of initiatives seeking to improve race relations.

Despite these actions, events of late show us that change is slow moving, and there are indications that many still wish to undermine or hinder any progress, as they refuse to acknowledge that present-day racial injustice exists. Others take this belief further, suggesting that certain details concerning America’s dark history shouldn’t be taught to children for fear that White children may experience guilt or shame while children from racial minority groups may feel inferior. Does banning the history of racial inequality from curricula improve or worsen the experiences of American children?

The current state of race relations in this country suggests that banning this history certainly will not improve the experiences of people of Color over their lifetimes. In recent weeks, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act has stalled in Congress and is unlikely to be enacted. Following the tragic death of a young woman, there’s been a groundswell of conversation about “missing White woman syndrome,” as thousands of people of Color are reported missing with little to no news coverage. There has been great criticism and passionate discussion about the perceived difference in treatment of Haitian immigrants at the United States border, as men were seen on horseback brandishing whips to subdue them. The list feels endless.

The issue of race is ever-present in American society, and the totality of events occurring in just the past year show that fleeting emotions alone don’t seem to promote real change. Unfortunate events thrust racial injustice into the greater society’s awareness for a moment, and then, in the next, many whose daily lives are unaffected return to business as usual.

I began experiencing race-related issues almost as early as I began to speak. My early recollections suggest that such experiences impact my present-day thoughts and behaviors. While I don’t have a magic wand or a “cure-all” for America’s “race problem,” I feel strongly that education about racial inequality is a step in the right direction. What led me to draw that conclusion?

At age 10, my testing results qualified me for the academically gifted program within my school district. I was transferred to a different school and placed in a class wherein I was one of only two Black children. I recall spending most lunches and recess periods alone. It took several years to acquire genuine friendship with some of my peers, but not without enduring race-based teasing about how I pronounced words, about how my hair grew, or about how our teachers must favor me because I performed well.

Years later, at age 28, I reconnected with one of those classmates, at which time he spontaneously apologized to me: “I took a diversity course in graduate school and had no idea how racist and insensitive the things we used to say to you were. I really just didn’t know the experiences of Black people.” Not only did I believe him, but I also readily accepted his apology . We were in the same classes between grades 5 and 12, and not once did we celebrate or learn Black American history. My formal education on the subject matter, too, was not acquired until I attended college, as I only knew my lived experiences. Who did that help or benefit? If we fail to teach this history, we ensure that we will remain “stuck” on whether there’s even a problem.

Atlanta Behavioral Health Advocates (ABHA) is an interprofessional and collaborative group of behavioral health professionals in Atlanta, Georgia engaged in social justice advocacy.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

American Racial and Ethnic Politics in the 21st Century: A cautious look ahead

Subscribe to governance weekly, jennifer l. hochschild jlh jennifer l. hochschild professor - government, harvard university.

March 1, 1998

- 12 min read

The course of American racial and ethnic politics over the next few decades will depend not only on dynamics within the African-American community, but also on relations between African Americans and other racial or ethnic groups. Both are hard to predict. The key question within the black community involves the unfolding relationship between material success and attachment to the American polity. The imponderable in ethnic relations is how the increasing complexity of ethnic and racial coalitions and of ethnicity-related policy issues will affect African-American political behavior. What makes prediction so difficult is not that there are no clear patterns in both areas. There are. But the current patterns are highly politically charged and therefore highly volatile and contingent on a lot of people s choices.

Material Success and Political Attachment

Today the United States has a thriving, if somewhat tenuous, black middle class. By conventional measures of income, education, or occupation at least a third of African Americans can be described as middle class, as compared with about half of whites. That is an astonishing–probably historically unprecedented–change from the early 1960s, when blacks enjoyed the “perverse equality” of almost uniform poverty in which even the best-off blacks could seldom pass on their status to their children. Conversely, the depth of poverty among the poorest blacks is matched only by the length of its duration. Thus, today there is greater disparity between the top fifth and the bottom fifth of African Americans, with regard to income, education, victimization by violence, occupational status, and participation in electoral politics, than between the top and bottom fifths of white Americans.

An observer from Mars might suppose that the black middle class would be highly gratified by its recent and dramatic rise in status and that persistently poor blacks would be frustrated and embittered by their unchanging or even worsening fate. But today’s middle-class African Americans express a “rage,” to quote one popular writer, that has, paradoxically, grown along with their material holdings. In the 1950s and 1960s, African Americans who were well-off frequently saw less racial discrimination, both generally and in their own lives, than did those who were poor. Poor and poorly educated blacks were more likely than affluent or well-educated blacks to agree that “whites want to keep blacks down” rather than to help them or simply to leave them alone. But by the 1980s blacks with low status were perceiving less white hostility than were their higher-status counterparts.

Recent evidence confirms affluent African Americans’ greater mistrust of white society. More college-educated blacks than black high school dropouts believe that it is true or might be true that “the government deliberately investigates black elected officials in order to discredit them,” that “the government deliberately makes sure that drugs are easily available in poor black neighborhoods in order to harm black people,” and that “the virus which causes AIDS was deliberately created in a laboratory in order to infect black people.” In a 1995 Washington Post survey, when asked whether “discrimination is the major reason for the economic and social ills blacks face,” 84 percent of middle-class blacks, as against 66 percent of working-class and poor blacks, agreed.

Ironically, today most poor and working-class African Americans remain committed to what Gunnar Myrdal called “the great national suggestion” of the American Creed. That is a change; in the 1960s, more well-off than poor blacks agreed that “things are getting better…for Negroes in this country.” But, defying logic and history, since the 1980s poor African Americans have been much more optimistic about the eventual success of the next generation of their race than have wealthy African Americans. They are more likely to agree that motivation and hard work produce success, and they are often touchingly gratified by their own or their children s progress.

Assume for the moment that these two patterns, of “succeeding more and enjoying it less” for affluent African Americans, and “remaining under the spell of the great national suggestion” for poor African Americans, persist and grow even stronger. That suggests several questions for political actors.

It is virtually unprecedented for a newly successful group of Americans to grow more and more alienated from the mainstream polity as it attains more and more material success. One exception, David Mayhew notes, is South Carolina’s plantation owners in the 1840s and 1850s. That frustrated group led a secessionist movement; what might embittered and resource-rich African Americans do? At this point the analogy breaks down: the secessionists’ actions had no justification, whereas middle-class blacks have excellent reason to be intensely frustrated with the persistent, if subtle, racial barriers they constantly meet. If more and more successful African Americans become more and more convinced of what Orlando Patterson calls “the homeostatic…principle of the…system of racial domination”–racism is squelched in one place, only to arise with renewed force in another–racial interactions in the political arena will be fraught with tension and antagonism over the next few decades.

In that case, ironically, it may be working-class blacks’ continued faith in the great national suggestion that lends stability to Americans’ racial encounters. If most poor and working-class African Americans continue to care more about education, jobs, safe communities, and decent homes than about racial discrimination and antagonism per se, they may provide a counterbalance in the social arena to the political and cultural rage of the black middle class.

But if these patterns should be reversed–thus returning us to the patterns of the 1960s–quite different political implications and questions would follow. For example, it is possible that the United States is approaching a benign “tipping point,” when enough blacks occupy prominent positions that whites no longer resist their success and blacks feel that American society sometimes accommodates them instead of always the reverse. That point is closer than it ever has been in our history, simply because never before have there been enough successful blacks for whites to have to accommodate them. In that case, the wealth disparities between the races will decline as black executives accumulate capital. The need for affirmative action will decline as black students SAT scores come to resemble those of whites with similar incomes. The need for majority-minority electoral districts will decline as whites discover that a black representative could represent them.

But what of the other half of a reversion to the pattern of 1960s beliefs, when poor blacks mistrusted whites and well-off blacks, and saw little reason to believe that conventional political institutions were on their side? If that view were to return in full force, among people now characterized by widespread ownership of fiirearms and isolation in communities with terrible schools and few job opportunities, there could indeed be a fire next time.

One can envision, of course, two other patterns–both wealthy and poor African Americans lose all faith, or both wealthy and poor African Americans regain their faith that the American creed can be put into practice. The corresponding political implications are not hard to discern. My point is that the current circumstances of African Americans are unusual and probably not stable. Political engagement and policy choices over the next few decades will determine whether affluent African Americans come to feel that their nation will allow them to enjoy the full social and psychological benefits of their material success, as well as whether poor African Americans give up on a nation that has turned its back on them. Racial politics today are too complicated to allow any trend, whether toward or away from equality and comity, to predominate. Political leaders’ choices, and citizens’ responses, are up for grabs.

Ethnic Coalitions and Antagonisms

America is once again a nation of immigrants, as a long series of recent newspaper stories and policy analyses remind us. Since 1990 the Los Angeles metropolitan region has gained almost a million residents, the New York region almost 400,000, and the Chicago region 360,000–almost all from immigration or births to recent immigrants. Most of the nation’s fastest-growing cities are in the West and Southwest, and their growth is attributable to immigration. More than half of the residents of New York City are immigrants or children of immigrants. How will these demographic changes affect racial politics?

Projections show that the proportion of Americans who are neither white nor black will continue to increase, dramatically so in some regions. By 2030, whites will become a smaller proportion of the total population of the nation as a whole, and their absolute numbers will begin to decrease. The black population, now just over 13 percent, will grow, but slowly. The number of Latinos, however, will more than double, from 24 million in 1990 to almost 60 million in 2030 (absent a complete change in immigration laws). The proportion of Asians will also double.

A few states will be especially transformed. By 2030 Florida’s population is projected to double; by then its white population, now about seven times as large as either the black or Latino population, will be only three or four times as large. And today, of 30 million Californians, 56 percent are white, 26 percent Latino, 10 percent Asian, and 7 percent black. By 2020, when California’s population could grow by as much as 20 million (10 million of them new immigrants), only 35 percent of its residents are projected to be white; 40 percent will be Latino, 17 percent Asian, and 8 percent black.

These demographic changes may have less dramatic effects on U.S. racial politics than one might expect. For example, the proportion of voters who are white is much higher than the proportion of the population that is white in states such as California and Florida, and that disproportion is likely to continue for some decades. Second, some cities, states, and even whole regions will remain largely unaffected by demographic change. Thus racial and ethnic politics below the national level will be quite variable, and even in the national government racial and ethnic politics will be diluted and constrained compared with the politics in states particularly affected by immigration. Third, most Latino and Asian immigrants are eager to learn English, to become Americans, and to be less insulated in ethnic communities, so their basic political framework may not differ much from that of native-born Americans.

Finally, there are no clear racial or ethnic differences on many political and policy issues; the fault lines lie elsewhere. For example, in the 1995 Washington Post survey mentioned earlier, whites, blacks, Latinos, and Asians showed similar levels of support for congressional action to limit tax breaks for business (under 40 percent), balance the budget (over 75 percent), reform Medicare (about 55 percent), and cut personal income taxes (about 50 percent). Somewhat more variation existed in support for reforming the welfare system (around 75 percent support) and limiting affirmative action (around a third). The only issue that seriously divided survey participants was increased limits on abortion: 24 percent support among Asian Americans, 50 percent support among Latinos, and 35 percent and 32 percent support among whites and blacks respectively. Other surveys show similar levels of inter-ethnic support for proposals to reduce crime, balance the federal budget, or improve public schooling.

But when political disputes and policy choices are posed, as they frequently are, along lines that allow for competition among racial or ethnic groups, the picture looks quite different. African Americans are overwhelmingly likely (82 percent) to describe their own group as the one that “faces the most discrimination in America today.” Three in five Asian Americans agree that blacks face the most discrimination, as do half of whites. But Latinos split evenly (42 percent to 40 percent) over whether to award African Americans or themselves this dubious honor. The same pattern appears in more specific questions about discrimination. Blacks are consistently more likely to see bias against their own race than against others in treatment by police, portrayals in the media, the criminal justice system, promotion to management positions, and the ability to get mortgages and credit loans. Latinos are split between blacks and their own group on all these questions, whereas whites see roughly as much discrimination against all three of the nonwhite groups and Asians vary across the issues.

Perhaps the most telling indicator of the coming complexity in racial and ethnic politics is a 1994 National Conference survey asking representatives of the four major ethnic groups which other groups share the most and the least in common with their own group. According to the survey, whites feel most in common with blacks, who feel little in common with whites. Blacks feel most in common with Latinos, who feel least in common with them. Latinos feel most in common with whites, who feel little in common with them. Asian Americans feel most in common with whites, who feel least in common with them. Each group is running after another that is fleeing from it. If these results hold up in political activity, then American racial and ethnic politics in the 21st century are going to be interesting, to say the least.

Attitudes toward particular policy issues show even more clearly the instability of racial and ethnic coalitions. Latinos support strong forms of affirmative action more than do whites and Asians, but sometimes less than do blacks. In a 1995 survey, whites were much more likely to agree strongly than were blacks, Asians, and Latinos that Congress should “limit affirmative action.” But the converse belief–that Congress should not limit affirmative action–received considerable support only from African Americans. Across a variety of surveys, blacks are always the most likely to support affirmative action for blacks; blacks and Latinos concur frequently on weaker though still majority support for affirmative action for Latinos, and all groups concur in lack of strong support for affirmative action for Asians. Exit polls on California”s Proposition 209 banning affirmative action found that 60 percent of white voters, 43 percent of Asian voters, and just over one-quarter of black and Latino voters supported the ban.

What might seem a potential coalition between blacks and Latinos is likely to break down, however–as might the antagonism between blacks and whites–if the issue shifts from affirmative action to immigration policy. The data are too sparse to be certain of any conclusion, especially for Asian Americans, but Latinos and probably Asians are more supportive of policies to encourage immigration and offer aid to immigrants than are African Americans and whites. A recent national poll by the Princeton Survey Research Associates suggests why African Americans and whites resemble each other and differ from Latinos in their preferences for immigration policy: without exception they perceive the effects of immigration–on such things as crime, employment, culture, politics, and the quality of schools–to be less favorable than do Latinos.

Taking advantage of the possibilities

We can only guess at this point about how the complicated politics of racial and ethnic competition and coalition-building will connect with the equally complicated politics of middle-class black alienation and poor black marginality. These are quintessentially political questions; the economic and demographic trajectories merely set the conditions for an array of political possibilities ranging from assimilation to a racial and ethnic cold war. I conclude only with the proposal that there is more room for racial and ethnic comity than we sometimes realize because most political issues cut across group lines–but achieving that comity will require the highly unlikely combination of strong leadership and sensitive negotiation.

Governance Studies

Sub-Saharan Africa

Kerllen Costa

March 28, 2024

Camille Busette, Keon L. Gilbert, Gabriel R. Sanchez, Kwadwo Frimpong, Carly Bennett

Morley Winograd, Michael Hais

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford scholars examine systemic racism, how to advance racial justice in America

Black History Month is an opportunity to reflect on the Black experience in America and examine continuing systemic racism and discrimination in the U.S. – issues many Stanford scholars are tackling in their research and scholarship.

A pandemic that disproportionately affected communities of color, roadblocks that obstructed efforts to expand the franchise and protect voting discrimination, a growing movement to push anti-racist curricula out of schools – events over the past year have only underscored how prevalent systemic racism and bias is in America today.

What can be done to dismantle centuries of discrimination in the U.S.? How can a more equitable society be achieved? What makes racism such a complicated problem to solve? Black History Month is a time marked for honoring and reflecting on the experience of Black Americans, and it is also an opportunity to reexamine our nation’s deeply embedded racial problems and the possible solutions that could help build a more equitable society.

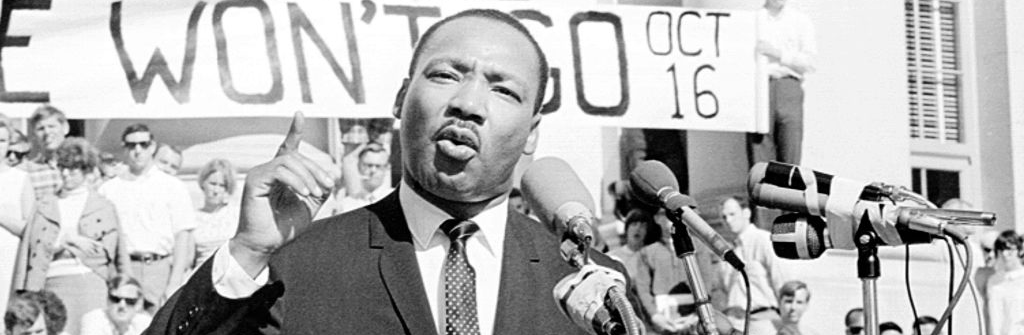

Stanford scholars are tackling these issues head-on in their research from the perspectives of history, education, law and other disciplines. For example, historian Clayborne Carson is working to preserve and promote the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and religious studies scholar Lerone A. Martin has joined Stanford to continue expanding access and opportunities to learn from King’s teachings; sociologist Matthew Clair is examining how the criminal justice system can end a vicious cycle involving the disparate treatment of Black men; and education scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students.

Learn more about these efforts and other projects examining racism and discrimination in areas like health and medicine, technology and the workplace below.

Update: Jan. 27, 2023: This story was originally published on Feb. 16, 2021, and has been updated on a number of occasions to include new content.

Understanding the impact of racism; advancing justice

One of the hardest elements of advancing racial justice is helping everyone understand the ways in which they are involved in a system or structure that perpetuates racism, according to Stanford legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks.

“The starting point for the center is the recognition that racial inequality and division have long been the fault line of American society. Thus, addressing racial inequity is essential to sustaining our nation, and furthering its democratic aspirations,” said Banks , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and co-founder of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice .

This sentiment was echoed by Stanford researcher Rebecca Hetey . One of the obstacles in solving inequality is people’s attitudes towards it, Hetey said. “One of the barriers of reducing inequality is how some people justify and rationalize it.”

How people talk about race and stereotypes matters. Here is some of that scholarship.

For Black Americans, COVID-19 is quickly reversing crucial economic gains

Research co-authored by SIEPR’s Peter Klenow and Chad Jones measures the welfare gap between Black and white Americans and provides a way to analyze policies to narrow the divide.

How an ‘impact mindset’ unites activists of different races

A new study finds that people’s involvement with Black Lives Matter stems from an impulse that goes beyond identity.

For democracy to work, racial inequalities must be addressed

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice is taking a hard look at the policies perpetuating systemic racism in America today and asking how we can imagine a more equitable society.

The psychological toll of George Floyd’s murder

As the nation mourned the death of George Floyd, more Black Americans than white Americans felt angry or sad – a finding that reveals the racial disparities of grief.

Seven factors contributing to American racism

Of the seven factors the researchers identified, perhaps the most insidious is passivism or passive racism, which includes an apathy toward systems of racial advantage or denial that those systems even exist.

Scholars reflect on Black history

Humanities and social sciences scholars reflect on “Black history as American history” and its impact on their personal and professional lives.

The history of Black History Month

It's February, so many teachers and schools are taking time to celebrate Black History Month. According to Stanford historian Michael Hines, there are still misunderstandings and misconceptions about the past, present, and future of the celebration.

Numbers about inequality don’t speak for themselves

In a new research paper, Stanford scholars Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt propose new ways to talk about racial disparities that exist across society, from education to health care and criminal justice systems.

Changing how people perceive problems

Drawing on an extensive body of research, Stanford psychologist Gregory Walton lays out a roadmap to positively influence the way people think about themselves and the world around them. These changes could improve society, too.

Welfare opposition linked to threats of racial standing

Research co-authored by sociologist Robb Willer finds that when white Americans perceive threats to their status as the dominant demographic group, their resentment of minorities increases. This resentment leads to opposing welfare programs they believe will mainly benefit minority groups.

Conversations about race between Black and white friends can feel risky, but are valuable

New research about how friends approach talking about their race-related experiences with each other reveals concerns but also the potential that these conversations have to strengthen relationships and further intergroup learning.

Defusing racial bias

Research shows why understanding the source of discrimination matters.

Many white parents aren’t having ‘the talk’ about race with their kids

After George Floyd’s murder, Black parents talked about race and racism with their kids more. White parents did not and were more likely to give their kids colorblind messages.

Stereotyping makes people more likely to act badly

Even slight cues, like reading a negative stereotype about your race or gender, can have an impact.

Why white people downplay their individual racial privileges

Research shows that white Americans, when faced with evidence of racial privilege, deny that they have benefited personally.

Clayborne Carson: Looking back at a legacy

Stanford historian Clayborne Carson reflects on a career dedicated to studying and preserving the legacy of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

How race influences, amplifies backlash against outspoken women

When women break gender norms, the most negative reactions may come from people of the same race.

Examining disparities in education

Scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students. Annamma’s research examines how schools contribute to the criminalization of Black youths by creating a culture of punishment that penalizes Black children more harshly than their white peers for the same behavior. Her work shows that youth of color are more likely to be closely watched, over-represented in special education, and reported to and arrested by police.

“These are all ways in which schools criminalize Black youth,” she said. “Day after day, these things start to sediment.”

That’s why Annamma has identified opportunities for teachers and administrators to intervene in these unfair practices. Below is some of that research, from Annamma and others.

New ‘Segregation Index’ shows American schools remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and economic status

Researchers at Stanford and USC developed a new tool to track neighborhood and school segregation in the U.S.

New evidence shows that school poverty shapes racial achievement gaps

Racial segregation leads to growing achievement gaps – but it does so entirely through differences in school poverty, according to new research from education Professor Sean Reardon, who is launching a new tool to help educators, parents and policymakers examine education trends by race and poverty level nationwide.

School closures intensify gentrification in Black neighborhoods nationwide

An analysis of census and school closure data finds that shuttering schools increases gentrification – but only in predominantly Black communities.

Ninth-grade ethnic studies helped students for years, Stanford researchers find

A new study shows that students assigned to an ethnic studies course had longer-term improvements in attendance and graduation rates.

Teaching about racism

Stanford sociologist Matthew Snipp discusses ways to educate students about race and ethnic relations in America.

Stanford scholar uncovers an early activist’s fight to get Black history into schools

In a new book, Assistant Professor Michael Hines chronicles the efforts of a Chicago schoolteacher in the 1930s who wanted to remedy the portrayal of Black history in textbooks of the time.

How disability intersects with race

Professor Alfredo J. Artiles discusses the complexities in creating inclusive policies for students with disabilities.

Access to program for black male students lowered dropout rates

New research led by Stanford education professor Thomas S. Dee provides the first evidence of effectiveness for a district-wide initiative targeted at black male high school students.

How school systems make criminals of Black youth

Stanford education professor Subini Ancy Annamma talks about the role schools play in creating a culture of punishment against Black students.

Reducing racial disparities in school discipline

Stanford psychologists find that brief exercises early in middle school can improve students’ relationships with their teachers, increase their sense of belonging and reduce teachers’ reports of discipline issues among black and Latino boys.

Science lessons through a different lens

In his new book, Science in the City, Stanford education professor Bryan A. Brown helps bridge the gap between students’ culture and the science classroom.

Teachers more likely to label black students as troublemakers, Stanford research shows

Stanford psychologists Jennifer Eberhardt and Jason Okonofua experimentally examined the psychological processes involved when teachers discipline black students more harshly than white students.

Why we need Black teachers

Travis Bristol, MA '04, talks about what it takes for schools to hire and retain teachers of color.

Understanding racism in the criminal justice system

Research has shown that time and time again, inequality is embedded into all facets of the criminal justice system. From being arrested to being charged, convicted and sentenced, people of color – particularly Black men – are disproportionately targeted by the police.

“So many reforms are needed: police accountability, judicial intervention, reducing prosecutorial power and increasing resources for public defenders are places we can start,” said sociologist Matthew Clair . “But beyond piecemeal reforms, we need to continue having critical conversations about transformation and the role of the courts in bringing about the abolition of police and prisons.”

Clair is one of several Stanford scholars who have examined the intersection of race and the criminal process and offered solutions to end the vicious cycle of racism. Here is some of that work.

Police Facebook posts disproportionately highlight crimes involving Black suspects, study finds

Researchers examined crime-related posts from 14,000 Facebook pages maintained by U.S. law enforcement agencies and found that Facebook users are exposed to posts that overrepresent Black suspects by 25% relative to local arrest rates.

Supporting students involved in the justice system

New data show that a one-page letter asking a teacher to support a youth as they navigate the difficult transition from juvenile detention back to school can reduce the likelihood that the student re-offends.

Race and mass criminalization in the U.S.

Stanford sociologist discusses how race and class inequalities are embedded in the American criminal legal system.

New Stanford research lab explores incarcerated students’ educational paths

Associate Professor Subini Annamma examines the policies and practices that push marginalized students out of school and into prisons.

Derek Chauvin verdict important, but much remains to be done

Stanford scholars Hakeem Jefferson, Robert Weisberg and Matthew Clair weigh in on the Derek Chauvin verdict, emphasizing that while the outcome is important, much work remains to be done to bring about long-lasting justice.

A ‘veil of darkness’ reduces racial bias in traffic stops

After analyzing 95 million traffic stop records, filed by officers with 21 state patrol agencies and 35 municipal police forces from 2011 to 2018, researchers concluded that “police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias.”

Stanford big data study finds racial disparities in Oakland, Calif., police behavior, offers solutions

Analyzing thousands of data points, the researchers found racial disparities in how Oakland officers treated African Americans on routine traffic and pedestrian stops. They suggest 50 measures to improve police-community relations.

Race and the death penalty

As questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system dominate the headlines, research by Stanford law Professor John J. Donohue III offers insight into one of the most fraught areas: the death penalty.

Diagnosing disparities in health, medicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color and has highlighted the health disparities between Black Americans, whites and other demographic groups.

As Iris Gibbs , professor of radiation oncology and associate dean of MD program admissions, pointed out at an event sponsored by Stanford Medicine: “We need more sustained attention and real action towards eliminating health inequities, educating our entire community and going beyond ‘allyship,’ because that one fizzles out. We really do need people who are truly there all the way.”

Below is some of that research as well as solutions that can address some of the disparities in the American healthcare system.

Stanford researchers testing ways to improve clinical trial diversity

The American Heart Association has provided funding to two Stanford Medicine professors to develop ways to diversify enrollment in heart disease clinical trials.

Striking inequalities in maternal and infant health

Research by SIEPR’s Petra Persson and Maya Rossin-Slater finds wealthy Black mothers and infants in the U.S. fare worse than the poorest white mothers and infants.

More racial diversity among physicians would lead to better health among black men

A clinical trial in Oakland by Stanford researchers found that black men are more likely to seek out preventive care after being seen by black doctors compared to non-black doctors.

A better measuring stick: Algorithmic approach to pain diagnosis could eliminate racial bias

Traditional approaches to pain management don’t treat all patients the same. AI could level the playing field.

5 questions: Alice Popejoy on race, ethnicity and ancestry in science

Alice Popejoy, a postdoctoral scholar who studies biomedical data sciences, speaks to the role – and pitfalls – of race, ethnicity and ancestry in research.

Stanford Medicine community calls for action against racial injustice, inequities

The event at Stanford provided a venue for health care workers and students to express their feelings about violence against African Americans and to voice their demands for change.

Racial disparity remains in heart-transplant mortality rates, Stanford study finds

African-American heart transplant patients have had persistently higher mortality rates than white patients, but exactly why still remains a mystery.

Finding the COVID-19 Victims that Big Data Misses

Widely used virus tracking data undercounts older people and people of color. Scholars propose a solution to this demographic bias.

Studying how racial stressors affect mental health

Farzana Saleem, an assistant professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education, is interested in the way Black youth and other young people of color navigate adolescence—and the racial stressors that can make the journey harder.

Infants’ race influences quality of hospital care in California

Disparities exist in how babies of different racial and ethnic origins are treated in California’s neonatal intensive care units, but this could be changed, say Stanford researchers.

Immigrants don’t move state-to-state in search of health benefits

When states expand public health insurance to include low-income, legal immigrants, it does not lead to out-of-state immigrants moving in search of benefits.

Excess mortality rates early in pandemic highest among Blacks

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been starkly uneven across race, ethnicity and geography, according to a new study led by SHP's Maria Polyakova.

Decoding bias in media, technology

Driving Artificial Intelligence are machine learning algorithms, sets of rules that tell a computer how to solve a problem, perform a task and in some cases, predict an outcome. These predictive models are based on massive datasets to recognize certain patterns, which according to communication scholar Angele Christin , sometimes come flawed with human bias .

“Technology changes things, but perhaps not always as much as we think,” Christin said. “Social context matters a lot in shaping the actual effects of the technological tools. […] So, it’s important to understand that connection between humans and machines.”

Below is some of that research, as well as other ways discrimination unfolds across technology, in the media, and ways to counteract it.

IRS disproportionately audits Black taxpayers

A Stanford collaboration with the Department of the Treasury yields the first direct evidence of differences in audit rates by race.

Automated speech recognition less accurate for blacks

The disparity likely occurs because such technologies are based on machine learning systems that rely heavily on databases of English as spoken by white Americans.

New algorithm trains AI to avoid bad behaviors

Robots, self-driving cars and other intelligent machines could become better-behaved thanks to a new way to help machine learning designers build AI applications with safeguards against specific, undesirable outcomes such as racial and gender bias.

Stanford scholar analyzes responses to algorithms in journalism, criminal justice

In a recent study, assistant professor of communication Angèle Christin finds a gap between intended and actual uses of algorithmic tools in journalism and criminal justice fields.

Move responsibly and think about things

In the course CS 181: Computers, Ethics and Public Policy , Stanford students become computer programmers, policymakers and philosophers to examine the ethical and social impacts of technological innovation.

Homicide victims from Black and Hispanic neighborhoods devalued

Social scientists found that homicide victims killed in Chicago’s predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods received less news coverage than those killed in mostly white neighborhoods.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

AI Index Diversity Report: An Unmoving Needle

Stanford HAI’s 2021 AI Index reveals stalled progress in diversifying AI and a scarcity of the data needed to fix it.

Identifying discrimination in the workplace and economy

From who moves forward in the hiring process to who receives funding from venture capitalists, research has revealed how Blacks and other minority groups are discriminated against in the workplace and economy-at-large.

“There is not one silver bullet here that you can walk away with. Hiring and retention with respect to employee diversity are complex problems,” said Adina Sterling , associate professor of organizational behavior at the Graduate School of Business (GSB).

Sterling has offered a few places where employers can expand employee diversity at their companies. For example, she suggests hiring managers track data about their recruitment methods and the pools that result from those efforts, as well as examining who they ultimately hire.

Here is some of that insight.

How To: Use a Scorecard to Evaluate People More Fairly

A written framework is an easy way to hold everyone to the same standard.

Archiving Black histories of Silicon Valley

A new collection at Stanford Libraries will highlight Black Americans who helped transform California’s Silicon Valley region into a hub for innovation, ideas.

Race influences professional investors’ judgments

In their evaluations of high-performing venture capital funds, professional investors rate white-led teams more favorably than they do black-led teams with identical credentials, a new Stanford study led by Jennifer L. Eberhardt finds.

Who moves forward in the hiring process?

People whose employment histories include part-time, temporary help agency or mismatched work can face challenges during the hiring process, according to new research by Stanford sociologist David Pedulla.

How emotions may result in hiring, workplace bias

Stanford study suggests that the emotions American employers are looking for in job candidates may not match up with emotions valued by jobseekers from some cultural backgrounds – potentially leading to hiring bias.

Do VCs really favor white male founders?

A field experiment used fake emails to measure gender and racial bias among startup investors.

Can you spot diversity? (Probably not)

New research shows a “spillover effect” that might be clouding your judgment.

Can job referrals improve employee diversity?

New research looks at how referrals impact promotions of minorities and women.

What were the main developments in race relations in the US, 1945-1968? #625Lab

- This is generally a really strong essay. I would say however, to avoid saying “in conclusion” in every paragraph, as there really is no need. Only say “in conclusion” in the conclusion.

- The introduction gives some really key background information and lays out the answer well. The flow of the essay is logical and reads really well. The conclusion is good too because it summarises the essay’s points, and then reopens the question with a quotation from Martin Luther King.

- You may also like: H1 Leaving Cert History Guide

- Post author: Martina

- Post published: March 27, 2018

- Post category: #625Lab History / History

You Might Also Like

What contribution did joseph goebbels and/or leni riefenstahl make to nazi propaganda #625lab, martin luther king and the montgomery bus boycott for leaving cert history #625lab, racial equality during 1945-1989 for leaving cert history #625lab.

What do Americans make of the state of race relations in 2021?

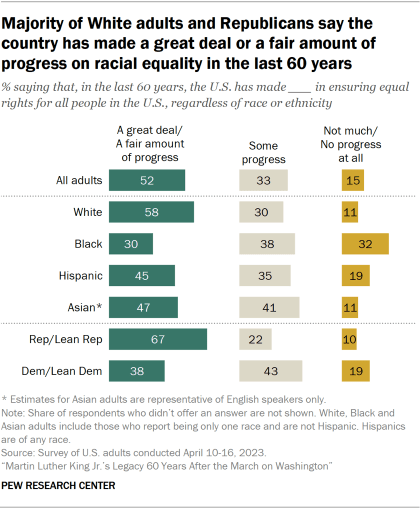

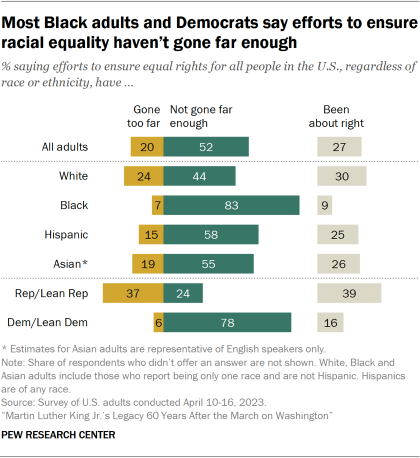

Ronald Reagan signed legislation establishing a national holiday to honor Dr. Martin Luther King , Jr. in 1983. But the day wasn’t observed in every state until 17 years later. Now, nearly four decades after it became a holiday, there are still Americans who don’t accept the holiday.

In the latest Economist /YouGov poll one-quarter (24%) think Dr. King’s day — celebrated on the third Monday of January, close to his January 15 birthday — should not be a national holiday.

Republicans (35%) are far less likely than Democrats (81%) or Independents (56%) to believe Martin Luther King’s birthday should be a national holiday. In fact, Republicans are more likely to say it should not be a federal holiday (42%). Black Americans (78%) and Hispanic Americans (66%) are much more likely than white Americans (50%) to believe the holiday should be recognized.

Whatever their party identification, most Americans recognize there are real concerns about race in America, that Dr. King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech is still relevant today, and that the protests of the Civil Rights Movement had a positive effect on the passage of major civil rights legislation. But Americans divide on whether protests are still necessary today in order to achieve racial equality.

By more than two to one, Black Americans say they are still necessary, but by 47% to 39%, white Americans say they are not. This is the case even though half of white respondents believe that only some – or even less – of Dr. King’s dream of equality has been yet achieved.

For most Americans, race relations remain a problem. When asked about the state of race relations in the United States today, most say they aren’t good, and they haven’t been good for a while. Today, two-thirds of Americans (65%) describe race relations in America as bad, compared to 40% in 2009.

While two in three Americans (64%) believed race relations were good throughout President Barack Obama ’s first term, that changed in the middle of his second term, starting after the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and have not improved during Donald Trump ’s presidency. Half (51%) of the public believe race relations have gotten worse in the last four years, including 48% of white Americans and 71% of Black Americans. Racism is seen as a very or somewhat serious problem by more Black Americans (87%) than white Americans (70%).

The public also sees a difference in law enforcement’s treatment of those who took over the US Capitol on January 6 and this summer’s Black Lives Matter protestors. Most believe that the police did not respond to the Capital takeover forcefully enough, and by more than two to one (50% vs 20%) Americans believe law enforcement treated Black Lives Matter protestors more harshly than they dealt with those who stormed the Capitol.

Republicans are less likely to see a distinction in the treatment of the two groups (42%), and when they do, they tend to say those who took over the Capitol were treated more harshly (41%).

Related: One week later, what do Americans make of the Capitol attack?

See the toplines and crosstabs from this week’s Economist/YouGov Poll

Methodology : The Economist survey was conducted by YouGov using a nationally representative sample of 1,500 US Adult Citizens interviewed online between January 10 - 12, 2021. This sample was weighted according to gender, age, race, and education based on the American Community Survey, conducted by the US Bureau of the Census, as well as 2016 Presidential vote, registration status, geographic region, and news interest. Respondents were selected from YouGov’s opt-in panel to be representative of all US citizens. The margin of error is approximately 3.6% for the overall sample.

Image: Getty

Explore more data & articles

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day

The Economist / YouGov polls

Compared to an average day, do you enjoy Leap Day (February 29)...?

Thanks to this year’s leap day, there is an extra working day in the calendar year. do you believe workers on an annual salary should be paid for an additional day of work during a leap year, compared to an average day, do you think being born on a leap day is..., which holidays do americans enjoy most — and least.

How immigration is taking center stage in 2024 politics

What the polls say about Nikki Haley’s campaign

Barack Obama sincerity

Barack obama favorability, democratic party ideology.

American Race Relations as a Social Construct Essay

Race relations have been a continuous part of the American history, from the horrors of slavery to the melting pot of immigration. Unfortunately, racism has become the focal point of interracial interaction, as any minority population faces challenges in a society dominated by the Caucasian race. Throughout history, racism has undertaken various forms. However, in contemporary times of supposed equality and acceptance, bigotry has become more covert and intractable. *Race relations in modern America are defined by institutionalized racism that has been masked under the means of microaggressions and political ignorance, with the only solution being a massive reform of social values.*

The whole concept of race division is a social construct that has roots in the incriminating injustices of American history. The domination of socio-political and economic structures by the Caucasian race is unparalleled. Despite some progress of past decades in racial equality, with a recent political emergence of the Republican party the tensions are growing again. The politics of aggrieved whiteness, a concept that seeks to maintain a Caucasian hegemony in the social order, has gained traction.

There is a strong political context to this development. Liberalism is associated with profligacy, beholden to minorities. Meanwhile, conservatism seeks to encourage individual values of hard work and, by extension, equality for all. Furthermore, any attempt by the government to recognize racial inequality through policy or welfare programs comes under fire for supposed social injustice that puts whites at a disadvantage.

Consequently, there is fanatical support for forms of repression against racial groups, such as Muslims, illegal immigrants, and urban African-American communities. This approach to politics makes it ultimately impossible to overcome social injustice since any meaningful attempts to make a difference are obstructed by the status quo of white supremacy. Despite this, an average class Caucasian person feels like reverse anti-white racism is the dominant form of racial discrimination (King).

“Our brains are hardwired to think in terms of place and to associate psychic value or meaning to the places we inhabit” (Dickey 7). The racial divide in America is often visible most clearly in urban communities. Certain neighborhoods are a hive of existence for racial groups, as their culture takes root there. While in most of America communities are more mixed, there are still privileged neighborhoods which are predominantly white.

The minority race in an opposing community would experience social unease and even covert discrimination. The racial tension is evident as the communities seek to conserve the status quo of their demographics, creating a sense of tribalism (Vance). Race is a primary factor in the American class structure, which, in turn, instigates social segregation, even if it is unintentional.

There is an entrenched concept of institutionalized racism in the nation which is largely ignored for more easily vilified interpersonal prejudices. There is no consensus or medium where such controversial topics can be discussed, with racial groups radically disagreeing on basic issues and politicians using it as an electorate tool (Blow). Race relations in current society have become a carefully avoided issue filled with superficial illusions to mask its core motives.

In the novel The Underground Railroad , such a phenomenon is accurately described, “But nobody wanted to speak on the true disposition of the world…Truth was a changing display in a shop window, manipulated by hands when you weren’t looking, alluring and ever out of reach” (Whitehead 143). The pretense of racism not existing in the light of evidence of its devastating consequences has nothing but a derogatory effect to prevent it from being a recurrent issue.

The most typical exemplification of racial issues can be seen in social behavior. Racism exists both in institutions and personal prejudices. However, in most communities, outright racism is condemned or illegal; therefore, people begin to exhibit it covertly.

This happens subconsciously, as the societal way of thought has been embedded into behavior since childhood. Such daily behaviors and verbal interaction is a psychological concept that is essentially a clandestine expression of racism as racial groups are insulted and degraded. These may have a basis in the national origin, education, culture values, criminality, or even competency (Sehgal).

A prominent example, which is also evidence of institutionalized racism, is the recent spike in police violence against African-Americans. The disproportionate police intervention including racial minorities, and, consequently, their imprisonment is unjustifiable. The whole concept of the racial, social construct has pragmatic evidence here, as a racial profile is established around the black community. News and media outlets aid in this by showing a biased perspective of African-Americans as either involved or associated with criminality.

Consequently, society begins to exhibit prejudice and fear, in turn, leading to a conflict based on irrationality, creating a social crisis. Claudia Rankine frankly identifies this concept in her prose, “because white men can’t police their imagination, black people are dying” (135).

With the result of recent elections, racial tensions began to emerge. The new leadership despite its promises to unite the nation has done only the opposite to address issues facing minorities. Polls show that the majority of African-Americans think race relations are at a low point and only getting worse. There are obvious schisms in the perception of social justice amongst races. Obama at one point stated, “we’ve been blind to the way past injustices continue to shape the present” (Sack and Thee-Brenan).

The task to challenge white hegemony which instigates the racial tension begins with an honest conversation. By understanding history and accepting identity, socio-political structures will be morphed to create a truly egalitarian society. Such processes may take generations, but until then, the status quo will persist if people choose to be ignorant to injustice.

Works Cited

Blow, Charles, “ The State of Race in America. ” New York Times. 2017. Web.

Dickey, Colin. Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places . Viking, 2016.

King, Michael. ” Aggrieved Whiteness: White Identity Politics and Modern American Racial Formation. ” Abolition Journal. 2017. Web.

Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric . Graywolf Press, 2014.

Sack, Kevin and Megan Thee-Brenan. “ Poll Finds Most in U.S. Hold Dim View of Race Relations ” New York Times. 2015. Web.

Sehgal, Priya. “ Racial Microaggressions: The Everyday Assault. ” American Psychiatric Association . 2016. Web.

Vance, James. “ The Racial Conversation We’re Having Today is Tribalistic .” National Review . 2016. Web.

Whitehead, Colson. The Underground Railroad . Doubleday, 2016.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, November 14). American Race Relations as a Social Construct. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-race-relations-as-a-social-construct/

"American Race Relations as a Social Construct." IvyPanda , 14 Nov. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/american-race-relations-as-a-social-construct/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'American Race Relations as a Social Construct'. 14 November.

IvyPanda . 2020. "American Race Relations as a Social Construct." November 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-race-relations-as-a-social-construct/.

1. IvyPanda . "American Race Relations as a Social Construct." November 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-race-relations-as-a-social-construct/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "American Race Relations as a Social Construct." November 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-race-relations-as-a-social-construct/.

- Social Factors of Educational and Career Choices

- Institutionalized Racism and Individualistic Racism

- Substance Abuse: The Harm Reduction Strategies

- Criminality and Personality Theory

- Covert Conflicts in Business Organizations

- Hegemony and Ideology

- The United States: Covert and Clandestine Operations

- Antonio Gramsci: On Hegemony and Direct Rule

- Relationship Between Institutionalized Racism and Marxism

- Overt vs. Covert Conflict

- Kansas State University Community's Racism Issues

- Racism Against Roma and Afro-American People

- Classism as a Complex Issue of Discrimination

- Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real About Race in School

- Courageous Conversations about Race

Module 10: World War II (1941-1945)

World war ii and race relations in the u.s., learning objectives.

- Analyze how the effects of WWII on the home front affected race relations in the United States

- Describe the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII

Social Tensions on the Home Front

The need for Americans to come together, whether in Hollywood, the defense industries, or the military, to support the war effort encouraged feelings of unity among the American population. However, the desire for unity did not always mean that Americans of color were treated as equals or even tolerated, despite their proclamations of patriotism and their willingness to join in the effort to defeat America’s enemies in Europe and Asia. For Black Americans, Mexican Americans, and especially for Japanese Americans, feelings of patriotism and willingness to serve one’s country both at home and abroad were not enough to guarantee equal treatment by White Americans or to prevent the U.S. government from regarding them as the enemy.

Black Americans and Double V

The Black community had, at the outset of the war, forged some promising relationships with the Roosevelt administration through civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune and Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet” of Black advisors. Through the intervention of Eleanor Roosevelt, Bethune was appointed to the advisory council set up by the War Department Women’s Interest Section. In this position, Bethune was able to organize the first officer candidate school for women and enable Black women to become officers in the Women’s Auxiliary Corps.

As the U.S. economy revived on the strength of government defense contracts, Black Americans wanted to ensure that their service to the country earned them better opportunities and more equal treatment. Accordingly, in 1942, after Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph pressured Roosevelt with a threatened “March on Washington,” the president created, by Executive Order 8802 , the Fair Employment Practices Committee. The purpose of this committee was to see that there was no discrimination in the defense industries. While they were effective in forcing defense contractors, such as the DuPont Corporation, to hire Black workers, they were not able to force corporations to place Black workers in well-paid positions. For example, at DuPont’s plutonium production plant in Hanford, Washington, Black Americans were hired as low-paid construction workers but not as laboratory technicians.

![race relations us essay A photograph shows five black men and a black woman participating in the Double V campaign. A young man sits at a typewriter, and the woman hands a man a pamphlet, the cover of which reads “This is a [Double V insignia] Home.” All wear armbands.](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images-archive-read-only/wp-content/uploads/sites/884/2015/08/23203225/CNX_History_27_02_DoubleV.jpg)

Figure 3. During World War II, Black Americans volunteered for government work just as White Americans did. These Washington, DC, residents have become civil defense workers as part of the Double V Campaign that called for victory at home and abroad.

CORE and the Double V Campaign

During the war, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded by James Farmer in 1942, used peaceful civil disobedience in the form of sit-ins to desegregate certain public spaces in Washington, DC, and elsewhere, as its contribution to the war effort. Members of CORE sought support for their movement by stating that one of their goals was to deprive the enemy of the ability to generate anti-American propaganda by accusing the United States of racism. After all, they argued, if the United States were going to denounce Germany and Japan for abusing human rights, the country should itself be as exemplary as possible. Indeed, CORE’s actions were in keeping with the goals of the Double V Campaign that was begun in 1942 by the Pittsburgh Courier , the largest Black newspaper at the time. The campaign called upon Black Americans to accomplish the two “Vs”: victory over America’s foreign enemies and victory over racism in the United States.

Migration Patterns and Racial Violence

Despite the willingness of Black Americans to fight for the United States, racial tensions often erupted in violence, as the geographic relocation necessitated by the war brought Black Americans into closer contact with White people. There were race massacres (formerly known as race riots) in Detroit, Harlem, and Beaumont, Texas, in which White residents responded with sometimes deadly violence to their new Black coworkers or neighbors. There were also racial incidents at or near several military bases in the South. Incidents of Black soldiers being harassed or assaulted occurred at Fort Benning, Georgia; Fort Jackson, South Carolina; Alexandria, Louisiana; Fayetteville, Arkansas; and Tampa, Florida. Black leaders such as James Farmer and Walter White, the executive secretary of the NAACP since 1931, were asked by General Eisenhower to investigate complaints of the mistreatment of Black servicemen while on active duty. They prepared a fourteen-point memorandum on how to improve conditions for Black Americans in the service, sowing some of the seeds of the postwar civil rights movement during the war years.

The Zoot Suit Riots

Mexican Americans also encountered racial prejudice. The Mexican American population in Southern California grew during World War II due to the increased use of Mexican agricultural workers in the fields to replace the White workers who had left for better paying jobs in the defense industries. The United States and Mexican governments instituted the Bracero Program on August 4, 1942, which sought to address the needs of California growers for manual labor to increase food production during wartime. The result was the immigration of thousands of impoverished Mexicans into the United States to work as braceros , or manual laborers.

Figure 4. A zoot suiter is arrested by the Los Angeles Police, on June 7, 1943, during the summer of the “zoot suit riots.”

Racial Violence Against Mexican Americans

Forced by racial discrimination to live in the barrios of East Los Angeles, many Mexican American youths sought to create their own identity and began to adopt a distinctive style of dress known as zoot suits , which were also popular among many young Black men. The zoot suits, which required large amounts of cloth to produce, violated wartime regulations that restricted the amount of cloth that could be used in civilian garments. Among the charges leveled at young Mexican Americans was that they were un-American and unpatriotic; wearing zoot suits was seen as evidence of this. Many native-born Americans also denounced Mexican American men for being unwilling to serve in the military, even though some 350,000 Mexican Americans either volunteered to serve or were drafted into the armed services. In the summer of 1943, “zoot-suit riots” occurred in Los Angeles when carloads of White sailors, encouraged by other White civilians, stripped and beat a group of young men wearing the distinctive form of dress. In retaliation, young Mexican American men attacked and beat up sailors. The response was swift and severe, as sailors and civilians went on a spree attacking young Mexican Americans on the streets, in bars, and in movie theaters. More than one hundred people were injured.

Japanese-American Internment

Japanese Americans also suffered from discrimination. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor unleashed a cascade of racist assumptions about Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans in the United States that culminated in the relocation and internment of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, 66 percent of whom had been born in the United States. Executive Order 9066 , signed by Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, gave the army power to remove people from “military areas” to prevent sabotage or espionage. The army then used this authority to relocate people of Japanese ancestry living along the Pacific coast of Washington, Oregon, and California, as well as in parts of Arizona, to internment camps in the American interior. Although a study commissioned earlier by Roosevelt indicated that there was little danger of disloyalty on the part of West Coast Japanese, fears of sabotage, perhaps spurred by the attempted rescue of a Japanese airman shot down at Pearl Harbor by Japanese living in Hawaii, as well as more generalized racist sentiments, led Roosevelt to act. Ironically, the Japanese in Hawaii were not interned. Although characterized afterward as America’s worst wartime mistake by Eugene V. Rostow in the September 1945 edition of Harper’s Magazine , the government’s actions were in keeping with decades of anti-Asian hostility on the West Coast.

Figure 5. Japanese Americans standing in line in front of a poster detailing internment orders in California.

After the order went into effect, Lt. General John L. DeWitt, in charge of the Western Defense Command, ordered approximately 127,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans—roughly 90 percent of those of Japanese ethnicity living in the United States—to assembly centers where they were transferred to hastily prepared camps in the interior of California, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Arkansas. Those who were sent to the camps reported that the experience was deeply traumatic. Families were sometimes separated. People could only bring a few of their belongings and had to abandon the rest of their possessions. The camps themselves were dismal and overcrowded. Despite the hardships, those in the camps attempted to build communities in the camps and resume “normal” life. Adults participated in camp government and worked at a variety of jobs. Children attended school, played basketball against local teams, and organized Boy Scout units. Nevertheless, they were imprisoned, and minor infractions, such as wandering too near the camp gate or barbed wire fences while on an evening stroll, could meet with severe consequences. Some sixteen thousand Germans, including some from Latin America, and German Americans were also placed in internment camps, as were 2,373 persons of Italian ancestry. However, they represented only a tiny percentage of the members of these ethnic groups living in the country. Most of these people were innocent of any wrongdoing, but some imprisoned Germans were members of the Nazi party. No interned Japanese Americans were found guilty of sabotage or espionage.

In its 1982 report, Personal Justice Denied , the congressionally appointed Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded that “the broad historical causes” shaping the relocation program were “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” [1] Although the exclusion orders were found to have been constitutionally permissible under the vagaries of national security, they were later judged, even by the military and judicial leaders of the time, to have been a grave injustice against people of Japanese descent.

Japanese Americans and Enlistment

Despite being singled out for special treatment, many Japanese Americans sought to enlist, but draft boards commonly classified them as 4-C: undesirable aliens. However, as the war ground on, some were reclassified as eligible for service. In total, nearly thirty-three thousand Japanese Americans served in the military during the war. Of particular note was the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, nicknamed the “Go For Broke,” which finished the war as the most decorated unit in U.S. military history given its size and length of service. While their successes, and the successes of Black pilots, were lauded, the country and the military still struggled to contend with its own racial tensions, even as the soldiers in Europe faced the brutality of Nazi Germany.

Watch this video to learn more about the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII.

You can view the transcript for “Ugly History: Japanese American incarceration camps – Densho” here (opens in new window) .

Link to LEARNING

This U.S. government propaganda film attempts to explain why the Japanese were interned.

Bracero Program: the policy of increased wartime use of immigrant agricultural labor to expand food production

Double V Campaign: a campaign by African Americans to win victory over the enemy overseas and victory over racism at home, first proposed in 1942 by the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper

Executive Order 8802: this Executive order created the Fair Employment Practices Committee which aimed to verify that there was no discrimination in the defense industries.

Executive Order 9066: the order given by President Roosevelt to relocate and detain people of Japanese ancestry, including those who were American citizens

internment: the forced eviction and confinement of the West Coast Japanese and Japanese American population into ten relocation centers for the greater part of World War II

zoot suit: a flamboyant outfit favored by young African American and Mexican American men

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982), 18). ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Scott Barr for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- US History. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- World War II. Provided by : The American Yawp. Located at : http://www.americanyawp.com/text/24-world-war-ii/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ugly History: Japanese American incarceration camps - Densho. Authored by : Lesson by Densho, directed by Lizete Upu012bte.. Provided by : TED-Ed. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hI4NoVWq87M . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Zoot suiter arrested by LAPD. Authored by : John T. Burns . Provided by : Associated Press . Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_man_in_a_zoot_suit_is_inspected_upon_arrest_by_LAPD_on_June_7,_1943.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Seth Royer's Leadership Site

"A leader is the one who knows the way, goes the way, and shows the way."

Race Relations Essay

Race Relations in America

Every country throughout the world has its problems that come and go, some faster than others. However, race relations have been a reoccurring problem for centuries around the world, whether it’s between Blacks and Whites, Whites and Hispanics, Asians and Europeans, or any other races. In the United States, specifically, race relations between Blacks and Whites have recently reached a point of conflict that the country has not seen since the 1960’s, a time where segregation plagued the country. While there are many theories as to what caused the spike in conflict between the two races, there is no argumentation on the fact that there is a prevalent issue between Blacks and Whites, and that it needs to be resolved. However, to discover how the relationship between Blacks and Whites has reached its current state, one must look back to the history of the two races in the United States.

The first white individuals to come to the territory now known as the “United States of America” arrived in the 16 th century. It was soon after, in the year of 1619, that the first black individuals were reported to be in the United States. Though both Blacks and Whites were now in America, the statuses of these two races were quite different. The Whites had come to America willingly to look for new resources, power and religious freedom. The Blacks, however, were forced against their will to come to the newfound territory as “indentured servants” or “slaves” of the white individuals. It was this initial act of misused power and forceful reign that set the precedent for the relationship between Blacks and Whites for centuries to come.