Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

72k Accesses

25 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Patrik Aspers & Ugo Corte

Qualitative Research: Ethical Considerations

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

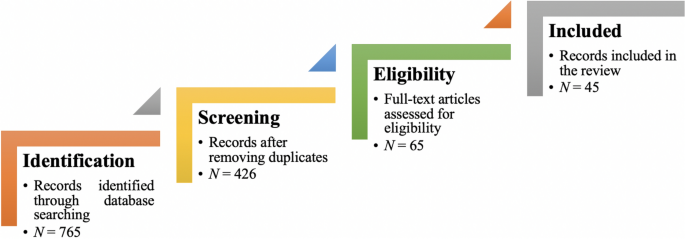

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

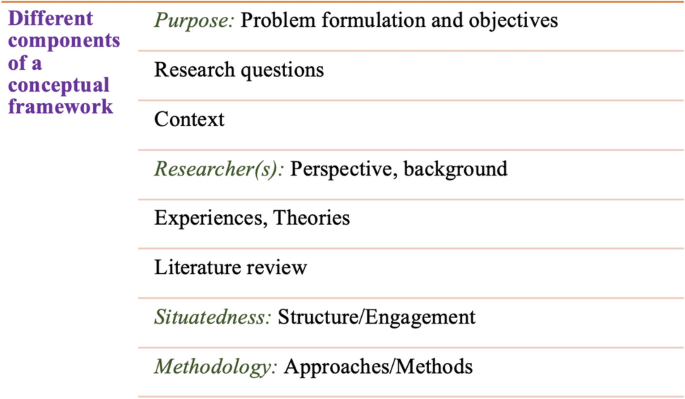

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Assessing quality in...

Assessing quality in qualitative research

- Related content

- Peer review

- Nicholas Mays , health adviser ( nicholas.mays{at}treasury.govt.nz ) a ,

- Catherine Pope , lecturer in medical sociology b

- a Social Policy Branch, The Treasury, PO Box 3724, Wellington, New Zealand

- b Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2PR

- Correspondence to: N Mays

This is the first in a series of three articles

In the past decade, qualitative methods have become more commonplace in areas such as health services research and health technology assessment, and there has been a corresponding rise in the reporting of qualitative research studies in medical and related journals. 1 Interest in these methods and their wider exposure in health research has led to necessary scrutiny of qualitative research. Researchers from other traditions are increasingly concerned to understand qualitative methods and, most importantly, to examine the claims researchers make about the findings obtained from these methods.

The status of all forms of research depends on the quality of the methods used. In qualitative research, concern about assessing quality has manifested itself recently in the proliferation of guidelines for doing and judging qualitative work. 2 – 5 Users and funders of research have had an important role in developing these guidelines as they become increasingly familiar with qualitative methods, but require some means of assessing their quality and of distinguishing “good” and “poor” quality research. However, the issue of “quality” in qualitative research is part of a much larger and contested debate about the nature of the knowledge produced by qualitative research, whether its quality can legitimately be judged, and, if so, how. This paper cannot do full justice to this wider epistemological debate. Rather it outlines two views of how qualitative methods might be judged and argues that qualitative research can be assessed according to two broad criteria: validity and relevance.

Summary points

Qualitative methods are now widely used and increasingly accepted in health research, but quality in qualitative research is a mystery to many health services researchers

There is considerable debate over the nature of the knowledge produced by such methods and how such research should be judged

Antirealists argue that qualitative and quantitative research are very different and that it is not possible to judge qualitative research by using conventional criteria such as reliability, validity, and generalisability

Quality in qualitative research can be assessed with the same broad concepts of validity and relevance used for quantitative research, but these need to be operationalised differently to take into account the distinctive goals of qualitative research

Two opposing views

There has been considerable debate over whether qualitative and quantitative methods can and should be assessed according to the same quality criteria. Extreme relativists hold that all research perspectives are unique and each is equally valid in its own terms, but this position means that research cannot derive any unequivocal insights relevant to action, and it would therefore command little support among applied health researchers. 6 Other than this total rejection of any quality criteria, it is possible to identify two broad, competing positions, for and against using the same criteria. 7 Within each position there is a range of views.

Separate and different: the antirealist position

Advocates of the antirealist position argue that qualitative research represents a distinctive paradigm and as such it cannot and should not be judged by conventional measures of validity, generalisability, and reliability. At its core, this position rejects naive realism—a belief that there is a single, unequivocal social reality or truth which is entirely independent of the researcher and of the research process; instead there are multiple perspectives of the world that are created and constructed in the research process. 8

Relativist criteria for quality 7

Degree to which substantive and formal theory is produced and the degree of development of such theory

Novelty of the claims made from the theory

Consistency of the theoretical claims with the empirical data collected

Credibility of the account to those studied and to readers

Extent to which the findings are transferable to other settings

Reflexivity of the account—that is, the degree to which the effects of the research strategies on the findings are assessed or the amount of information about the research process that is provided to readers

Those relativists who maintain that assessment criteria are feasible but that distinctive ones are required to evaluate qualitative research have put forward a range of different assessment schemes. In part, this is because the choice and relative importance of different criteria of quality depend on the topic and the purpose of the research. Hammersley has attempted to pull together these quality criteria (box). 7 These criteria are open to challenge (for example, it is arguable whether all research should be concerned to develop theory). At the same time, many of the criteria listed are not exclusive to qualitative research.

Using criteria from quantitative research: subtle realism

Other authors agree that all research involves subjective perception and that different methods produce different perspectives, but, unlike the anti-realists, they argue that there is an underlying reality which can be studied. 9 10 The philosophy of qualitative and quantitative researchers should be one of “subtle realism”—an attempt to represent that reality rather than to attain “the truth.” From this position it is possible to assess the different perspectives offered by different research processes against each other and against criteria of quality common to both qualitative and quantitative research, particularly those of validity and relevance. However, the means of assessment may be modified to take account of the distinctive goals of qualitative research. This is our position.

Assessing the validity of qualitative research

There are no mechanical or “easy” solutions to limit the likelihood that there will be errors in qualitative research. However, there are various ways of improving validity, each of which requires the exercise of judgment on the part of researcher and reader.

Triangulation

Triangulation compares the results from either two or more different methods of data collection (for example, interviews and observation) or, more simply, two or more data sources (for example, interviews with members of different interest groups). The researcher looks for patterns of convergence to develop or corroborate an overall interpretation. This is controversial as a genuine test of validity because it assumes that any weaknesses in one method will be compensated by strengths in another, and that it is always possible to adjudicate between different accounts (say, from interviews with clinicians and patients). Triangulation may therefore be better seen as a way of ensuring comprehensiveness and encouraging a more reflexive analysis of the data (see below) than as a pure test of validity.

Respondent validation

Respondent validation, or “member checking,” includes techniques in which the investigator's account is compared with those of the research subjects to establish the level of correspondence between the two sets. Study participants' reactions to the analyses are then incorporated into the study findings. Although some researchers view this as the strongest available check on the credibility of a research project, 8 it has its limitations. For example, the account produced by the researcher is designed for a wide audience and will, inevitably, be different from the account of an individual informant simply because of their different roles in the research process. As a result, it is better to think of respondent validation as part of a process of error reduction which also generates further original data, which in turn requires interpretation. 11

Clear exposition of methods of data collection and analysis

Since the methods used in research unavoidably influence the objects of inquiry (and qualitative researchers are particularly aware of this), a clear account of the process of data collection and analysis is important. By the end of the study, it should be possible to provide a clear account of how early, simpler systems of classification evolved into more sophisticated coding structures and thence into clearly defined concepts and explanations for the data collected. Although it adds to the length of research reports, the written account should include sufficient data to allow the reader to judge whether the interpretation proffered is adequately supported by the data.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity means sensitivity to the ways in which the researcher and the research process have shaped the collected data, including the role of prior assumptions and experience, which can influence even the most avowedly inductive inquiries. Personal and intellectual biases need to be made plain at the outset of any research reports to enhance the credibility of the findings. The effects of personal characteristics such as age, sex, social class, and professional status (doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, sociologist, etc) on the data collected and on the “distance” between the researcher and those researched also needs to be discussed.

Attention to negative cases

As well as exploration of alternative explanations for the data collected, a long established tactic for improving the quality of explanations in qualitative research is to search for, and discuss, elements in the data that contradict, or seem to contradict, the emerging explanation of the phenomena under study. Such “deviant case analysis” helps refine the analysis until it can explain all or the vast majority of the cases under scrutiny.

(Credit: LIANE PAYNE)

Fair dealing

The final technique is to ensure that the research design explicitly incorporates a wide range of different perspectives so that the viewpoint of one group is never presented as if it represents the sole truth about any situation.

Research can be relevant when it either adds to knowledge or increases the confidence with which existing knowledge is regarded. Another important dimension of relevance is the extent to which findings can be generalised beyond the setting in which they were generated. One way of achieving this is to ensure that the research report is sufficiently detailed for the reader to be able to judge whether or not the findings apply in similar settings. Another tactic is to use probability sampling (to ensure that the range of settings chosen is representative of a wider population, for example by using a stratified sample). Probability sampling is often ignored by qualitative researchers, but it can have its place. Alternatively, and more commonly, theoretical sampling ensures that an initial sample is drawn to include as many as possible of the factors that might affect variability of behaviour, and then this is extended, as required, in the light of early findings and emergent theory. 2 The full sample, therefore, attempts to include the full range of settings relevant to the conceptualisation of the subject.

Some questions about quality that might be asked of a qualitative study

Worth or relevance—Was this piece of work worth doing at all? Has it contributed usefully to knowledge?

Appropriateness of the design to the question—Would a different method have been more appropriate? For example, if a causal hypothesis was being tested, was a qualitative approach really appropriate?

Context—Is the context or setting adequately described so that the reader could relate the findings to other settings?

Sampling—Did the sample include the full range of possible cases or settings so that conceptual rather than statistical generalisations could be made (that is, more than convenience sampling)? If appropriate, were efforts made to obtain data that might contradict or modify the analysis by extending the sample (for example, to a different type of area)?

Data collection and analysis—Were the data collection and analysis procedures systematic? Was an “audit trail” provided such that someone else could repeat each stage, including the analysis? How well did the analysis succeed in incorporating all the observations? To what extent did the analysis develop concepts and categories capable of explaining key processes or respondents' accounts or observations? Was it possible to follow the iteration between data and the explanations for the data (theory)? Did the researcher search for disconfirming cases?

Reflexivity of the account—Did the researcher self consciously assess the likely impact of the methods used on the data obtained? Were sufficient data included in the reports of the study to provide sufficient evidence for readers to assess whether analytical criteria had been met?

Is there any place for quality guidelines?

Whether quality criteria should be applied to qualitative research, which criteria are appropriate, and how they should be assessed is hotly debated. It would be unwise to consider any single set of guidelines as definitive. We list some questions to ask of any piece of qualitative research (box); the questions emphasise criteria of relevance and validity. They could also be used by researchers at different times during the life of a particular research project to improve its quality.

Although the issue of quality in qualitative health and health services research has received considerable attention, a recent paper was able to argue, legitimately, that “quality in qualitative research is a mystery to many health services researchers.” 12 However, qualitative researchers can address the issue of quality in their research. As in quantitative research, the basic strategy to ensure rigour, and thus quality, in qualitative research is systematic, self conscious research design, data collection, interpretation, and communication. Qualitative research has much to offer. Its methods can, and do, enrich our knowledge of health and health care. It is not, however, an easy option or the route to a quick answer. As Dingwall et al conclude, “qualitative research requires real skill, a combination of thought and practice and not a little patience.” 12

Further reading

- Dingwall R ,

- Greatbatch D ,

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the HTA report on qualitative research methods by Elizabeth Murphy, Robert Dingwall, David Greatbatch, Susan Parker, and Pamela Watson to this paper. We thank these authors for their careful exposition of a tangled series of debates, and their timely publication of this literature review.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the New Zealand Treasury, in the case of NM. The Treasury takes no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of the information contained in this article.

Series editors Catherine Pope and Nicholas Mays

Competing interests None declared.

This article is taken from the second edition of Qualitative Research in Health Care , edited by Catherine Pope and Nicholas Mays, published by BMJ Books

- Harding G ,

- Boulton M ,

- Fitzpatrick R

- Wimbush E ,

- Hammersley M

- Lincoln YS ,

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Pediatr Psychol

Commentary: Writing and Evaluating Qualitative Research Reports

Yelena p. wu.

1 Division of Public Health, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of Utah,

2 Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Huntsman Cancer Institute,

Deborah Thompson

3 Department of Pediatrics-Nutrition, USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Baylor College of Medicine,

Karen J. Aroian

4 College of Nursing, University of Central Florida,

Elizabeth L. McQuaid

5 Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, and

Janet A. Deatrick

6 School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania

Objective To provide an overview of qualitative methods, particularly for reviewers and authors who may be less familiar with qualitative research. Methods A question and answer format is used to address considerations for writing and evaluating qualitative research. Results and Conclusions When producing qualitative research, individuals are encouraged to address the qualitative research considerations raised and to explicitly identify the systematic strategies used to ensure rigor in study design and methods, analysis, and presentation of findings. Increasing capacity for review and publication of qualitative research within pediatric psychology will advance the field’s ability to gain a better understanding of the specific needs of pediatric populations, tailor interventions more effectively, and promote optimal health.

The Journal of Pediatric Psychology (JPP) has a long history of emphasizing high-quality, methodologically rigorous research in social and behavioral aspects of children’s health ( Palermo, 2013 , 2014 ). Traditionally, research published in JPP has focused on quantitative methodologies. Qualitative approaches are of interest to pediatric psychologists given the important role of qualitative research in developing new theories ( Kelly & Ganong, 2011 ), illustrating important clinical themes ( Kars, Grypdonck, de Bock, & van Delden, 2015 ), developing new instruments ( Thompson, Bhatt, & Watson, 2013 ), understanding patients’ and families’ perspectives and needs ( Bevans, Gardner, Pajer, Riley, & Forrest, 2013 ; Lyons, Goodwin, McCreanor, & Griffin, 2015 ), and documenting new or rarely examined issues ( Haukeland, Fjermestad, Mossige, & Vatne, 2015 ; Valenzuela et al., 2011 ). Further, these methods are integral to intervention development ( Minges et al., 2015 ; Thompson et al., 2007 ) and understanding intervention outcomes ( de Visser et al., 2015 ; Hess & Straub, 2011 ). For example, when designing an intervention, qualitative research can identify patient and family preferences for and perspectives on desirable intervention characteristics and perceived needs ( Cassidy et al., 2013 ; Hess & Straub, 2011 ; Thompson, 2014 ), which may lead to a more targeted, effective intervention.

Both qualitative and quantitative approaches are concerned with issues such as generalizability of study findings (e.g., to whom the study findings can be applied) and rigor. However, qualitative and quantitative methods have different approaches to these issues. The purpose of qualitative research is to contribute knowledge or understanding by describing phenomenon within certain groups or populations of interest. As such, the purpose of qualitative research is not to provide generalizable findings. Instead, qualitative research has a discovery focus and often uses an iterative approach. Thus, qualitative work is often foundational to future qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods studies.

At the time of this writing, three of six current calls for papers for special issues of JPP specifically note that manuscripts incorporating qualitative approaches would be welcomed. Despite apparent openness to broadening JPP’s emphasis beyond its traditional quantitative approach, few published articles have used qualitative methods. For example, of 232 research articles published in JPP from 2012 to 2014 (excluding commentaries and reviews), only five used qualitative methods (2% of articles).

The goal of the current article is to present considerations for writing and evaluating qualitative research within the context of pediatric psychology to provide a framework for writing and reviewing manuscripts reporting qualitative findings. The current article may be especially useful to reviewers and authors who are less familiar with qualitative methods. The tenets presented here are grounded in the well-established literature on reporting and evaluating qualitative research, including guidelines and checklists ( Eakin & Mykhalovskiy, 2003 ; Elo et al., 2014 ; Mays & Pope, 2000 ; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007 ). For example, the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist describes essential elements for reporting qualitative findings ( Tong et al., 2007 ). Although the considerations presented in the current manuscript have broad applicability to many fields, examples were purposively selected for the field of pediatric psychology.

Our goal is that this article will stimulate publication of more qualitative research in pediatric psychology and allied fields. More specifically, the goal is to encourage high-quality qualitative research by addressing key issues involved in conducting qualitative studies, and the process of conducting, reporting, and evaluating qualitative findings. Readers interested in more in-depth information on designing and implementing qualitative studies, relevant theoretical frameworks and approaches, and analytic approaches are referred to the well-developed literature in this area ( Clark, 2003 ; Corbin & Strauss, 2008 ; Creswell, 1994 ; Eakin & Mykhalovskiy, 2003 ; Elo et al., 2014 ; Mays & Pope, 2000 ; Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2013 ; Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ; Saldaña, 2012 ; Sandelowski, 1995 , 2010 ; Tong et al., 2007 ; Yin, 2015 ). Researchers new to qualitative research are also encouraged to obtain specialized training in qualitative methods and/or to collaborate with a qualitative expert in an effort to ensure rigor (i.e., validity).

We begin the article with a definition of qualitative research and an overview of the concept of rigor. While we recognize that qualitative methods comprise multiple and distinct approaches with unique purposes, we present an overview of considerations for writing and evaluating qualitative research that cut across qualitative methods. Specifically, we present basic principles in three broad areas: (1) study design and methods, (2) analytic considerations, and (3) presentation of findings (see Table 1 for a summary of the principles addressed in each area). Each area is addressed using a “question and answer” format. We present a brief explanation of each question, options for how one could address the issue raised, and a suggested recommendation. We recognize, however, that there are no absolute “right” or “wrong” answers and that the most “right” answer for each situation depends on the specific study and its purpose. In fact, our strongest recommendation is that authors of qualitative research manuscripts be explicit about their rationale for design, analytic choices, and strategies so that readers and reviewers can evaluate the rationale and rigor of the study methods.

Summary of Overarching Principles to Address in Qualitative Research Manuscripts

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative methods are used across many areas of health research, including health psychology ( Gough & Deatrick, 2015 ), to study the meaning of people’s lives in their real-world roles, represent their views and perspectives, identify important contextual conditions, discover new or additional insights about existing social and behavioral concepts, and acknowledge the contribution of multiple perspectives ( Yin, 2015 ). Qualitative research is a family of approaches rather than a single approach. There are multiple and distinct qualitative methodologies or stances (e.g., constructivism, post-positivism, critical theory), each with different underlying ontological and epistemological assumptions ( Lincoln, Lynham, & Guba, 2011 ). However, certain features are common to most qualitative approaches and distinguish qualitative research from quantitative research ( Creswell, 1994 ).

Key to all qualitative methodologies is that multiple perspectives about a phenomenon of interest are essential, and that those perspectives are best inductively derived or discovered from people with personal experience regarding that phenomenon. These perspectives or definitions may differ from “conventional wisdom.” Thus, meanings need to be discovered from the population under study to ensure optimal understanding. For instance, in a recent qualitative study about texting while driving, adolescents said that they did not approve of texting while driving. The investigators, however, discovered that the respondents did not consider themselves driving while a vehicle was stopped at a red light. In other words, the respondents did approve of texting while stopped at a red light. In addition, the adolescents said that they highly valued being constantly connected via texting. Thus, what is meant by “driving” and the value of “being connected” need to be considered when approaching the issue of texting while driving with adolescents ( McDonald & Sommers, 2015 ).

Qualitative methods are also distinct from a mixed-method approach (i.e., integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches; Creswell, 2013b ). A mixed-methods study may include a first phase of quantitative data collection that provides results that inform a second phase of the study that includes qualitative data collection, or vice versa. A mixed-methods study may also include concurrent quantitative and qualitative data collection. The timing, priority, and stage of integration of the two approaches (quantitative and qualitative) are complex and vary depending on the research question; they also dictate how to attend to differing qualitative and quantitative principles ( Creswell et al., 2011 ). Understanding the basic tenets of qualitative research is preliminary to integrating qualitative research with another approach that has different tenets. A full discussion of the integration of qualitative and quantitative research approaches is beyond the scope of this article. Readers interested in the topic are referred to one of the many excellent resources on the topic ( Creswell, 2013b ).

What Are Typical Qualitative Research Questions?

Qualitative research questions are typically open-ended and are framed in the spirit of discovery and exploration and to address existing knowledge gaps. The current manuscript provides exemplar pediatric qualitative studies that illustrate key issues that arise when reporting and evaluating qualitative studies. Example research questions that are contained in the studies cited in the current manuscript are presented in Table 2 .

Example Qualitative Research Questions From the Pediatric Literature

What Are Rigor and Transparency in Qualitative Research?

There are several overarching principles with unique application in qualitative research, including definitions of scientific rigor and the importance of transparency. Quantitative research generally uses the terms reliability and validity to describe the rigor of research, while in qualitative research, rigor refers to the goal of seeking to understand the tacit knowledge of participants’ conception of reality ( Polanyi, 1958 ). For example, Haukeland and colleagues (2015) used qualitative analysis to identify themes describing the emotional experiences of a unique and understudied population—pediatric siblings of children with rare medical conditions such as Turner syndrome and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Within this context, the authors’ rendering of the diverse and contradictory emotions experienced by siblings of children with these rare conditions represents “rigor” within a qualitative framework.

While debate exists regarding the terminology describing and strategies for strengthening scientific rigor in qualitative studies ( Guba, 1981 ; Morse, 2015a , 2015b ; Sandelowski, 1993a ; Whittemore, Chase, & Mandle, 2001 ), little debate exists regarding the importance of explaining strategies used to strengthen rigor. Such strategies should be appropriate for the specific study; therefore, it is wise to clearly describe what is relevant for each study. For example, in terms of strengthening credibility or the plausibility of data analysis and interpretation, prolonged engagement with participants is appropriate when conducting an observational study (e.g., observations of parent–child mealtime interactions; Hughes et al., 2011 ; Power et al., 2015 ). For an interview-only study, however, it would be more practical to strengthen credibility through other strategies (e.g., keeping detailed field notes about the interviews included in the analysis).

Dependability is the stability of a data analysis protocol. For instance, stepwise development of a coding system from an “a priori” list of codes based on the underlying conceptual framework or existing literature (e.g., creating initial codes for potential barriers to medication adherence based on prior studies) may be essential for analysis of data from semi-structured interviews using multiple coders. But this may not be the ideal strategy if the purpose is to inductively derive all possible coding categories directly from data in an area where little is known. For some research questions, the strategy may be to strengthen confirmability or to verify a specific phenomenon of interest using different sources of data before generating conclusions. This process, which is commonly referred to in the research literature as triangulation, may also include collecting different types of data (e.g., interview data, observational data), using multiple coders to incorporate different ways of interpreting the data, or using multiple theories ( Krefting, 1991 ; Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ). Alternatively, another investigator may use triangulation to provide complementarity data ( Krefting, 1991 ) to garner additional information to deepen understanding. Because the purpose of qualitative research is to discover multiple perspectives about a phenomenon, it is not necessarily appropriate to attain concordance across studies or investigators when independently analyzing data. Some qualitative experts also believe that it is inappropriate to use triangulation to confirm findings, but this debate has not been resolved within the field ( Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ; Tobin & Begley, 2004 ). More agreement exists, however, regarding the value of triangulation to complement, deepen, or expand understanding of a particular topic or issue ( Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ). Finally, instead of basing a study on a sample that allows for generalizing statistical results to other populations, investigators in qualitative research studies are focused on designing a study and conveying the results so that the reader understands the transferability of the results. Strategies for transferability may include explanations of how the sample was selected and descriptive characteristics of study participants, which provides a context for the results and enables readers to decide if other samples share critical attributes. A study is deemed transferable if relevant contextual features are common to both the study sample and the larger population.

Strategies to enhance rigor should be used systematically across each phase of a study. That is, rigor needs to be identified, managed, and documented throughout the research process: during the preparation phase (data collection and sampling), organization phase (analysis and interpretation), and reporting phase (manuscript or final report; Elo et al., 2014 ). From this perspective, the strategies help strengthen the trustworthiness of the overall study (i.e., to what extent the study findings are worth heeding; Eakin & Mykhalovskiy, 2003 ; Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ).

A good example of managing and documenting rigor and trustworthiness can be found in a study of family treatment decisions for children with cancer ( Kelly & Ganong, 2011 ). The researchers describe how they promoted the rigor of the study and strengthening its credibility by triangulating data sources (e.g., obtaining data from children’s custodial parents, stepparents, etc.), debriefing (e.g., holding detailed conversations with colleagues about the data and interpretations of the data), member checking (i.e., presenting preliminary findings to participants to obtain their feedback and interpretation), and reviewing study procedure decisions and analytic procedures with a second party.

Transparency is another key concept in written reports of qualitative research. In other words, enough detail should be provided for the reader to understand what was done and why ( Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ). Examples of information that should be included are a clear rationale for selecting a particular population or people with certain characteristics, the research question being investigated, and a meaningful explanation of why this research question was selected (i.e., the gap in knowledge or understanding that is being investigated; Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ). Clearly describing recruitment, enrollment, data collection, and data analysis or extraction methods are equally important ( Dixon-Woods, Shaw, Agarwal, & Smith, 2004 ). Coherency among methods and transparency about research decisions adds to the robustness of qualitative research ( Tobin & Begley, 2004 ) and provides a context for understanding the findings and their implications.

Study Design and Methods

Is qualitative research hypothesis driven.

In contrast to quantitative research, qualitative research is not typically hypothesis driven ( Creswell, 1994 ; Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ). A risk associated with using hypotheses in qualitative research is that the findings could be biased by the hypotheses. Alternatively, qualitative research is exploratory and typically guided by a research question or conceptual framework rather than hypotheses ( Creswell, 1994 ; Ritchie & Lewis, 2003 ). As previously stated, the goal of qualitative research is to increase understanding in areas where little is known by developing deeper insight into complex situations or processes. According to Richards and Morse (2013) , “If you know what you are likely to find, … you should not be working qualitatively” (p. 28). Thus, we do not recommend that a hypothesis be stated in manuscripts presenting qualitative data.

What Is the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research?

Consistent with the exploratory nature of qualitative research, one particular qualitative method, grounded theory, is used specifically for discovering substantive theory (i.e., working theories of action or processes developed for a specific area of concern; Bryant & Charmaz, 2010 ; Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ). This method uses a series of structured steps to break down qualitative data into codes, organize the codes into conceptual categories, and link the categories into a theory that explains the phenomenon under study. For example, Kelly and Ganong (2011) used grounded theory methods to produce a substantive theory about how single and re-partnered parents (e.g., households with a step-parent) made treatment decisions for children with childhood cancer. The theory of decision making developed in this study included “moving to place,” which described the ways in which parents from different family structures (e.g., single and re-partnered parents) were involved in the child’s treatment decision-making. The resulting theory also delineated the causal conditions, context, and intervening factors that contributed to the strategies used for moving to place.