An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective

1 Shanghai University, Shanghai China

2 Curtin University, Perth Western Australia, 6000 Australia

3 Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875 China

Sharon K. Parker

Associated data.

Existing knowledge on remote working can be questioned in an extraordinary pandemic context. We conducted a mixed‐methods investigation to explore the challenges experienced by remote workers at this time, as well as what virtual work characteristics and individual differences affect these challenges. In Study 1, from semi‐structured interviews with Chinese employees working from home in the early days of the pandemic, we identified four key remote work challenges (work‐home interference, ineffective communication, procrastination, and loneliness), as well as four virtual work characteristics that affected the experience of these challenges (social support, job autonomy, monitoring, and workload) and one key individual difference factor (workers’ self‐discipline). In Study 2, using survey data from 522 employees working at home during the pandemic, we found that virtual work characteristics linked to worker's performance and well‐being via the experienced challenges. Specifically, social support was positively correlated with lower levels of all remote working challenges; job autonomy negatively related to loneliness; workload and monitoring both linked to higher work‐home interference; and workload additionally linked to lower procrastination. Self‐discipline was a significant moderator of several of these relationships. We discuss the implications of our research for the pandemic and beyond.

INTRODUCTION

As information and communication technologies (ICTs) have advanced in their capabilities, and especially with the greater availability of high‐speed internet, remote working (also referred to as teleworking, telecommuting, distributed work, or flexible work arrangements; Allen et al., 2015 ) has grown in its use as a new mode of work in the past several decades. Remote working is defined as “a flexible work arrangement whereby workers work in locations, remote from their central offices or production facilities, the worker has no personal contact with co‐workers there, but is able to communicate with them using technology” (Di Martino & Wirth, 1990 , p. 530).

However, prior to the pandemic, remote working was not a widely used practice (Kossek & Lautsch, 2018 ). Although the recent American Community Survey (2017) showed that the number of US employees who worked from home at least half of the time grew from 1.8 million in 2005 to 3.9 million in 2017, remote working at that time was just 2.9 percent of the total US workforce. Even in Europe, only around 2 percent of employees teleworked mainly from home in 2015 (Eurofound, 2017 ). Remote working has, in fact, been a “luxury for the relatively affluent” (Desilver, 2020 ), such as higher‐income earners (e.g., over 75% of employees who work from home have an annual earning above $65,000) and white‐collar workers (e.g., over 40% of teleworkers are executives, managers, or professionals).

Because of this situation, prior to COVID‐19, most workers had little remote working experience; nor were they or their organizations prepared for supporting this practice. Now, the unprecedented outbreak of the COVID‐19 pandemic in 2020 has required millions of people across the world into being remote workers, inadvertently leading to a de facto global experiment of remote working (Kniffin et al., 2020 ). Remote working has become the “new normal,” almost overnight.

As management scholars, we might assume that we already have a sufficient evidence base to understand the psychological challenges or risks that remote workers are facing during the pandemic, given the large body of research on remote working (e.g., Grant et al., 2013 ; Konradt et al., 2003 ). However, due to the fact that almost none of those studies was conducted at a time when remote working was practiced at such an unprecedented scale as it has been during the pandemic, coupled with unique demands at this time, some of the previously accumulated knowledge on remote working might lack contextual relevance in the current COVID‐19 crisis. At the least, we need to investigate how this context has shaped the experience of working remotely.

More specifically, existing knowledge on remote working has mostly been generated from a context in which remote working was only occasionally or infrequently practiced, and was only considered by some, but not all or most, of the workers within an organization. As criticized in Bailey and Kurland ( 2002 ), “[the] occasional, infrequent manner in which telework is practiced, likely has rendered mute many suspected individual‐level outcomes for the bulk of the teleworking population” (p. 396). In other words, there might be large differences in individual outcomes between those who do remote work extensively and those who do it infrequently, which likely affects the outcomes of this practice. In addition, because of the largely voluntary nature of prior remote working, in which people choose to work remotely at their own discretion, some of the previous findings on remote working have suffered from a selection bias (Lapierre et al., 2016 ). As such, the previously identified benefits of remote working might only, or especially, be true for those who are interested in, or able to engage in, remote working (Kaduk et al., 2019 ). In an unusual situation when remote working is no longer a discretionary option but rather a compulsory requirement or a mandatory order, there is a need to shift the research focus from understanding whether or not to implement remote working to understanding how to get the most out of remote working . Such a shift of research focus essentially requires a systematic understanding of the potential changed nature of the work itself in the different context.

For this endeavor, we draw on the theoretical perspective of work design. Work design refers to the content and organization of work tasks , activities , relationships , and responsibilities (Parker, 2014 ). Indeed, the concept of work design encompasses the notion of remote work (since working virtually represents a different “organization” of one's tasks compared to working in the office), and has been argued to be relevant to other contemporary work changes, such as the current digital era (e.g., Bélanger et al., 2013 ; Parker & Grote, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Research from diverse theoretical perspectives on work design has generally converged to suggest that when work is designed in such a way as to result in particular “work characteristics,” then it will also generate well‐being, job satisfaction, performance, and other such positive outcomes. For example, a meta‐analysis by Humphrey et al. ( 2007 ) identified a range of motivational, knowledge, social, and physical work characteristics as predicting desirable employee outcomes (e.g., better performance and well‐being, positive psychological states, job satisfaction, etc.).

Applying the work design perspective to our investigation on the remote working practice during the pandemic, we expect to observe a powerful role of virtual work characteristics (i.e., work characteristics of one's remote work) in shaping working experiences. In the following sections, we briefly review existing knowledge about work design in the remote working literature and argue why exploratory research is required in the COVID‐19 context. We then present our mixed‐methods research to explore how virtual work characteristics shape working experiences in the unique context wrought by the pandemic. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our research beyond the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

WORK DESIGN AND REMOTE WORKING: AN OVERVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Work design is one of the most influential theoretical perspectives in existing remote working literature. As shown in Table Table1, 1 , based on a literature review, we identified three different types of positioning of work design in the existing literature, or three approaches.

Different Types of Positioning of Work Characteristics in the Remote Working Literature

In the first approach, remote working (i.e., remote working intensity and whether taking up this policy or not) is an independent variable that predicts remote worker outcomes, with perceived work characteristics as a moderator. For example, Golden and Gajendran ( 2019 ) found that the positive relationship between remote working intensity and job performance was stronger for employees low in social support at work. A second approach regards work characteristics as mediating between remote working as the independent variable and employee outcomes as the dependent variables, thus considering how engaging in remote working affects individuals through shaping the perceived nature of their work. Still taking relational aspects of work as an example, Vander Elst et al.’s ( 2017 ) study revealed that the extent of remote working negatively related to perceived social support, which in turn led to more emotional exhaustion. Both approaches regard one's work as a whole that encompasses both remote and non‐remote components, with the independent variable capturing the extent of each aspect. In contrast, in a third approach, the focus is on just the experience of remote work. Scholars in this stream of literature are interested in how virtual work characteristics shape work experiences within the context of remote work. Received social support during the period of working away from office, for instance, can help remote workers to overcome social isolation (Bentley et al., 2016 ).

These three approaches have different assumptions and serve to address distinct research questions. In what follows, we discuss each of the three approaches in more detail.

Approach 1: Work Characteristics as Moderating the Effect of Remote Work on Outcomes

In this approach, remote working intensity is the independent variable that affects individual outcomes, and (other) work characteristics are identified as moderators. This approach lends itself to identifying what sort of work is most suited to remote working. Thus, as Golden and Veiga ( 2005 ) stated, “whether individuals can fully benefit from telecommuting is likely to be influenced by the way in which they must perform their work activities” (p. 303). Building upon the premise that remote working policy is only suitable for certain types of jobs (Pinsonneault & Boisvert, 2001 ), this approach considers employees’ work characteristics as boundary conditions to reconcile the mixed impacts of engaging in remote working. The key implication from these studies is that managers should provide remote working for appropriate jobs and workers (Golden & Veiga, 2005 ).

Golden and colleagues have conducted several studies to support this argument. Taking their classical study as an example, based on a sample of 273 telecommuters and their supervisors, Golden and Gajendran ( 2019 ) found that the positive relationship between the extent of remote working (i.e., the percentage of time spent on remote working per week) and supervisor‐rated job performance was more pronounced for those working in complex jobs, those with lower task interdependence, and those receiving lower social support. Similar studies have shown that the impact of remote working on well‐being also depends on other work characteristics, including task interdependence and job autonomy (e.g., Golden & Veiga, 2005 ; Golden et al., 2006 ; Perry et al., 2018 ).

Approach 2: Work Characteristics as Mediating the Effect of Remote Work on Outcomes

The first approach builds on the assumption that the nature of the work will not be influenced by remote working practices and, therefore, one's work characteristics could be considered as criteria that managers use to design remote working policy. The second approach, in contrast, argues that—as most tasks, communications, and interpersonal collaborations are mediated by ICTs in remote working—how an individual experiences his/her work design (or one's work characteristics) is changed by taking up flexible working policy.

Specifically, engaging in remote work practices can significantly change job demands, autonomy, and relational aspects of work, which in turn influence employee outcomes. In Kelliher and Anderson’s ( 2010 ) qualitative study, most remote workers experienced work intensification, because they can stay away from interruptions in the office and work more intensely. A considerable number of studies have found positive impacts of remote working on autonomy (e.g., Gajendran et al., 2015 ; Ter Hoeven & Van Zoonen, 2015 ). Gajendran and Harrison’s ( 2007 ) meta‐analysis also supported the beneficial effect of remote working on perceived autonomy, which in turn was associated with desirable individual outcomes (e.g., task performance and job satisfaction). Finally, studies suggest that remote working is usually detrimental for the relational aspects of work. Based on 93 interviews, Cooper and Kurland’s ( 2002 ) qualitative study revealed that telecommuters experienced more professional isolation when they missed opportunities to engage in developmental activities at work.

Approach 3: Work Characteristics as Antecedents in the Context of Remote Work

The meaning of work design in the third approach is different from its counterparts in the first two approaches, because it particularly refers to characteristics of one's remote work (i.e., what does one's work look like during home office days). This stream of literature derives from the socio‐technical systems perspective (Trist, 1981 ; Trist & Bamforth, 1951 ), which regards remote work as a context rather than an independent variable, arguing that characteristics of remote work should fit the new way of working to achieve better performance and well‐being (Bélanger et al., 2013 ). Unintended outcomes might arise when virtual work characteristics fail to meet individual and/or task requirements. Work‐to‐family conflicts, for example, could occur where there are intolerable job demands and limited autonomy for remote workers during home days.

Overall, however, few studies have adopted this third approach. Existing research has mainly focused on impacts of virtual work characteristics on well‐being. For example, in one study, workplace support for teleworkers was positively associated with job satisfaction (Baker et al., 2006 ). Bentley et al. ( 2016 ) also found indirect effects of social support from supervisors and the organization on psychological strain and job satisfaction via reducing social isolation in remote working practices. In addition to social support, research has shown that perceived control over the location, timing, and process of work was negatively related to teleworkers’ work‐family conflict and turnover intentions (Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, 2009 ), and task‐related demands (e.g., time pressure and uncertainty) were positively associated with teleworkers’ experienced stress (Turetken et al., 2011 ).

Summary and the Current Research

The first two approaches have provided valuable evidence to evaluate and design remote working policy prior to the pandemic. For example, one crucial implication from those studies is that managers should provide such a policy to appropriate people and appropriate jobs. However, remote working was no longer optional during the pandemic; instead, the COVID‐19 outbreak has forced people to be working from home irrespective of their preferences, abilities, and the nature of their jobs. In other words, during the pandemic remote working has become a “new normal,” or a new context, rendering the third approach to be of high importance.

The advantage of this third approach is that it frames remote working as a context/setting (Bailey & Kurland, 2002 ), and focuses on the relationship between virtual work characteristics and working experiences. This approach has important theoretical and practical implications, and it is especially valuable for understanding remote working experiences in the COVID‐19 context.

From the theoretical standpoint, the effects of work characteristics vary with contexts (Morganson, Major, Oborn, Verive, & Heelan, 2010 ). Johns ( 2006 ) pointed out that context is “a shaper of meaning.” For example, people tend to evaluate their achievements more negatively when in a generally superior group versus in a generally inferior group (i.e., the frog pond effect). Similarly, the meaning of some work characteristics may have been shaped by the unique pandemic context. For instance, being socially connected with colleagues may have different meanings during the COVID‐19 lockdown, in which most social gatherings are not allowed, as opposed to being connected in the “normal” workplace. Potentially, even limited social support can have strong positive spillover effects when social resources people pursue are hard to obtain. Kawohl and Nordt ( 2020 ), for example, suggested that social support plays a crucial role in suicide prevention during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Moreover, in contrast to the scarcity of social resources, job autonomy is usually relatively high in the current context. According to Warr’s ( 1994 ) vitamin model, however, negative effects may result from too much of a good thing. Workers with higher autonomy might potentially be distracted by their family issues and unable to concentrate on their work at home. In sum, given the uniqueness and novelty of the pandemic, we should explore and examine the work design theory in the current extreme context, including what virtual work characteristics really matter and how they matter ( that is , which challenges do they help address ).

From the practical standpoint, existing studies from approaches 1 and 2 built on the premise that remote working is optional and aimed to identify which types of jobs and people are suitable for remote working. However, people were required to work from home due to the COVID‐19 outbreak. Some scholars even believe that the pandemic will make some jobs permanently remote (Sytch & Greer, 2020 ). Thus, it is also practically important and necessary to explore how to get the most out of remote working. The third approach, focusing on the role of virtual work characteristic and its associated outcomes, can provide valuable evidence for managers to boost employees’ productivity and well‐being via re‐designing remote work appropriately.

Accordingly, we adopted the third approach and conducted mixed‐methods research to explore how virtual work characteristics shape remote working experiences . Specifically, in Study 1 (a qualitative explorative study), we—based on interviews with 39 participants who worked from home during the pandemic—developed a theoretical framework to integrate the relationships among virtual work characteristics, remote work challenges, and individual outcomes. In Study 2, a cross‐sectional online survey study, we collected data from 522 employees having remote working experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic to quantitatively examine the identified links.

STUDY 1: A QUALITATIVE EXPLORATIVE STUDY

To build the theoretical foundation of the current research, we adopted a grounded theory approach to capture remote workers’ first‐hand accounts of their experiences and challenges while they were working from home during the COVID‐19 outbreak.

Study 1 Method and Procedure

In mid‐February 2020, a significant proportion of workers across the major cities in mainland China were forced to work from home. As soon as we obtained ethics approval for our research, we recruited remote workers for interviews through social media (e.g., WeChat, QQ, etc.). We recruited 39 full‐time employees (15 of them were from Beijing) who were required by their organizations to work from home until further notice. The first author and two research assistants conducted semi‐structured interviews with each of the participants in Chinese using audio calls or video calls, which were recorded and then transcribed. Data collection was completed when we reached theoretical saturation; that is, we were not able to identify a new category/theme from the interviews (Strauss & Corbin, 1998 ).

Participants were employed in a wide range of industries (e.g., education, IT, media, finance, etc.) and occupations (e.g., managers, teachers, designers, etc.). They had an average age of 32.62 years ( SD = 9.43) and 23 of them were women; 15 of them were married and 18 of them had caring responsibilities. Participants worked 7.27 hours per day on average ( SD = 2.39) and by the time they were interviewed they had worked from home for an average of 20.41 days ( SD = 10.45). Notably, flexible work arrangements such as remote working are relatively new in China. In 2018, only 0.6 percent of the workforce (4.9 million Chinese employees) had remote working experiences. Most Chinese workers in our sample worked away from the office for the first time during the COVID‐19 situation. In our study, only one participant (#4) was an experienced remote worker.

Participants were asked to generally describe their working experiences (i.e., work performance and well‐being) during the period of working from home. As participants might narrowly focus on specific aspects of remote working experiences, we generated a list of questions before we conducted the interviews (for these questions, see Appendix A ), which helped us to get a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. Participants were then asked to indicate potential factors that shaped their work performance and well‐being during this period. On average, an interview lasted for 15.62 minutes (ranging from 10 to 42 minutes; SD = 7.11).

Study 1 Data Analysis

Following previous recommendations for coding qualitative data (Creswell, 2003 ), it is necessary for researchers to deeply immerse themselves in the research context. The first author had worked remotely in his hometown located in southern China for 3 weeks during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Thus, he was knowledgeable regarding remote working experiences in China and the COVID‐19 context.

We followed a three‐step approach in analyzing the qualitative data. The first author conducted open coding to analyze the raw interview data. With the first interview, he conducted open coding by going through the interview transcript line by line. He particularly focused on participants’ narratives (i.e., words, sentences, or paragraphs) about factors that were influencing their work performance and well‐being. In vivo codes (i.e., words, sentences, or paragraphs in participant's language) were identified in this step. Second, we considered the shared properties/dimensions among first‐order in vivo codes and then grouped similar first‐order codes into a more abstract second‐order category. Codes and categories emerging from the first interview were used to analyze the next interview transcript; newly identified codes in turn can help to refine, elaborate, and develop existing concepts and interrelationships. After coding all 39 interviews, we unified second‐order categories around central phenomena based on work design theories (e.g., job demands‐resources model, Demerouti et al., 2001 ) and existing literature on remote working (e.g., Allen et al., 2015 ). Throughout this process, co‐authors assessed the categories and themes identified by the first author. Conflicts were resolved through discussion.

Study 1 Findings

Table Table1 1 provides representative first‐order in vivo codes, second‐order categories, and shows the three aggregated main themes that we identified from the categories. We identified that remote work challenges (theme 1), virtual work characteristics (theme 2), and individual factors (theme 3) were crucial for remote workers’ performance and well‐being during the pandemic (Table (Table2 2 ).

Themes and Codes Identified from Study 1 Interviews

Theme 1: Remote Work Challenges

Remote work challenges reflect workers’ immediate psychological experiences in accomplishing tasks, interpersonal collaborations, and social interactions with family and friends. We identified four key challenges in the remote work context during the pandemic, namely procrastination, ineffective communication, work‐home interference, and loneliness. Generally, those four challenges exerted detrimental impacts on individuals’ work effectiveness and well‐being.

Work‐Home Interference

Most participants (26 out of 39) mentioned that they were struggling with home ‐ to ‐ work interference (HWI) and work ‐ to ‐ home interference (WHI). First, working at home means more interruptions from family, which may negatively influence work effectiveness. Notably, schools in China had been shut down during the COVID‐19 outbreak; working parents, therefore, faced a bigger challenge in balancing work and family roles. In addition, individuals’ work invaded their life domains during the period of working from home. These interferences from work domains could make people feel exhausted. A project manager (#23) shared her experience of being “always online”: “I’m basically always online…my supervisors and colleagues may come to me whenever they need something from me, and you have to give immediate response.” The need to be always online affected this project manager's ability to meet her family obligations.

Ineffective Communication

Remote workers rely heavily on ICTs to communicate and collaborate with colleagues, supervisors, and clients. Especially during the pandemic, ICT‐mediated communications almost become the only option because workers were not able to engage in face‐to‐face meetings. Twenty‐one participants identified that they suffered from low productivity caused by poor communications during this period. For example, a manager (#32) described experiencing lower efficiency in ICT‐mediated communications: “I feel that online communication is not as efficient as face‐to‐face communications in the office. [Online] communication has a time cost.”

Procrastination

Procrastination, defined as the irrational delay of behavior (Steel, 2007 ), is one of the biggest productivity killers at work. Procrastination is common in the office‐based workplace (Kühnel et al., 2016 ) and it can become even worse when people work from home. Although most participants were committed to working productively as usual, they sometimes were struggling with self‐regulation failure. Fourteen participants indicated procrastination as a challenge whilst working from home. We found that these participants delayed working on their core tasks via spending time on non‐work‐related activities during working hours, such as using social media and having long breaks (#1).

Remote working means fewer face‐to‐face interactions with colleagues and supervisors. Given the restrictions on non‐essential social gatherings during the pandemic, people also lost social opportunities to meet their friends or colleagues, which inevitably contributed to the feeling of loneliness. Ten participants indicated loneliness as a challenge. For instance, participant #4 suggested that though individuals can connect with colleagues via ICTs, conversations with colleagues were more task‐focused, which could not meet her psychological needs for belongingness or relatedness.

Theme 2: Virtual Work Characteristics

Virtual work characteristics reflect the nature or quality of the worker's job during the period of working from home. We identified four crucial virtual work characteristics: social support, job autonomy, monitoring, and workload. Our participants suggested that virtual work characteristics usually influenced their work effectiveness and well‐being in an indirect manner, that is, via shaping their experienced challenges in remote working.

Job Autonomy

Thirteen participants suggested the role of job autonomy in remote working. Job autonomy means employees can decide when and how to accomplish their tasks. Individuals’ performance and well‐being benefit from job autonomy, as those with higher job autonomy can balance work and rest and choose the most productive ways to do their work. Job autonomy was also identified as beneficial for work‐family balance. For example, participant 14 stated: “I can control the rhythms of work and rest. If it is not during the meeting, I can have a short break, around ten to thirty minutes, and then continue to work. That also means more time to spend time with my family.”

Monitoring in remote work has rarely been discussed (Lautsch et al., 2009 ). Ten participants reported that they experienced different forms of monitoring from their supervisors, including daily reports, clocking in/out via applications such as DingTalk, and being required to have a camera on whilst working. In the current sample, most comments about monitoring were positive. Some participants reported that monitoring can help them to cope with procrastination and to concentrate on their core tasks. A business analyst (#1), for instance, described his experiences of extra morning meetings, which was previously not a routine activity in the office: “After this morning meeting, you will feel a sense of ritual and you will devote yourself to work.”

Ten participants mentioned workload during remote working. Participants indicated that workload influenced their work‐home balance. Participant #39 complained about heavy workload during this period: “I don't think remote working can give me more personal time; instead, I feel that remote work increases my working time.” Workload also relates to procrastination. Participant 3 noted that low workload means more opportunities to procrastinate. Also suggesting a link between workload and focus, a top‐level manager (#36) who had to deal with lots of urgent business caused by COVID‐19 stated: “I cannot stop even if I wanted to.”

Social Support

Seven participants mentioned social support in remote working, and they indicated social support as necessary job resources to accomplish tasks during the period of working from home. More importantly, social support is conducive to overcome loneliness. Participants whose organization provided online platforms to boost social interactions among workers usually reported less loneliness. For instance, participant 2 stated: “We discussed about work on enterprise social media [DingTalk] and chatted in WeChat. I do not feel isolated.”

Theme 3: Individual Factors (Personal Traits)

Although we were primarily interested in how virtual work characteristics shape remote working experiences, one powerful individual factor (or personal trait) emerged from the interview data—self‐discipline. Twelve participants highlighted the importance of this aspect. Participants who indicated they were less disciplined reported experiencing more self‐control failures, such as procrastination (#9) and cyberloafing (#4), making them less productive in remote working. Those participants who identified themselves as more disciplined, in contrast, reported that they completed their work in a more efficient and timely manner (#2). Participant #36 also emphasized the benefit of self‐discipline for work‐family balance.

Interestingly, disciplined and less‐disciplined people evaluated the impact of some aspects of work design differently. Notably, monitoring was mentioned as particularly useful for less‐disciplined workers. As participant #18 mentioned: “I’m not a self‐disciplined person. If there is no external pressure [monitoring], I will be very indolent.”

Study 1 Summary and Discussion

Findings generated from the interview study reveal that a set of challenges in remote working during the pandemic negatively affect individuals’ work effectiveness and well‐being. In addition, virtual work characteristics and self‐discipline jointly shape the extent of these experienced challenges. We recognize that many of the work characteristics that we identified are important and indeed overlap to some extent with prior research on flexible working. However, this was in part the point: to explore whether this would be so, and to assess the applicability of work design theory, in the very different context of the pandemic.

Crucially, we also identified some unique findings. First, existing studies have showed that taking up remote working policy can reduce work‐family conflict (e.g., Allen et al., 2015 ; Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ). However, this conclusion is challenged by our findings, that is, work‐home interference was the most‐mentioned challenge in remote working during the pandemic for this sample. In addition, previous research suggested that extra monitoring would be harmful for remote workers (Lautsch et al., 2009 ). That might be possible because flexible working arrangement is only made available for the “right” workers (e.g., disciplined people), and they can work productively in their home offices even without supervisory controls. However, in the interview study, we found that remote workers (at least in our sample) believed monitoring was necessary for coping with procrastination, which is different from results that were identified in the pre‐pandemic context.

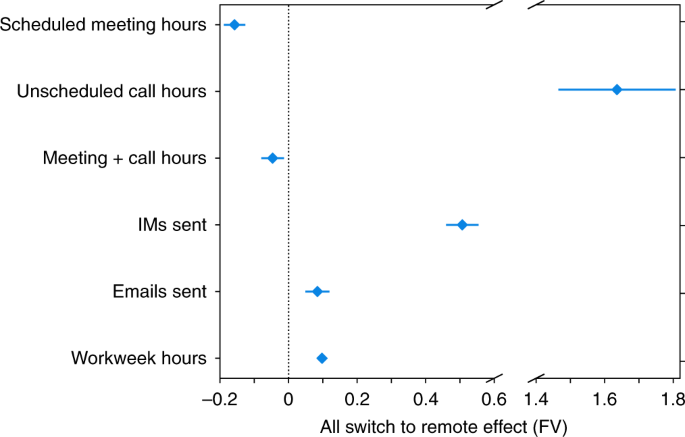

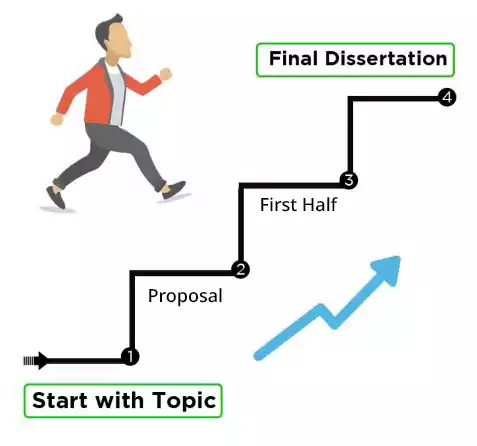

Based on the work design perspective, we now integrate the above findings into a theoretical model to explain how virtual work characteristics matter in the current remote work context (see Figure Figure1 1 ).

Theoretical framework identified from Study 1. Note . Although we did not analyze the relationship between the four virtual work characteristics and the challenge of ineffective communication in Study 1, we still include it in our framework because this challenge might be influenced by other virtual work characteristics such as technical support, task interdependence, and task complexity (e.g., Bélanger et al., 2013 ; Marlow et al., 2017 ).

Building upon our interviews, in conjunction with work design theories (e.g., Demerouti et al., 2001 ), we expect that social support will be a key work characteristic in this unique COVID‐19 context. Though some scholars have raised concern about the loss of social connections in remote work practices (e.g., Olszewski & Mokhtarian, 1994 ), the social distancing policy limited employees’ opportunities to obtain social resources, rendering social support from work of ever increasing importance. Individuals who receive considerable social support at work will suffer less from loneliness, because social support can bring desirable online social interactions to meet their needs for belonging (Bavik et al., 2020 ). In addition, social support also can provide necessary emotional and instrumental resources for people to handle challenges in interactions with their family (e.g., Kossek et al., 2011 ). Therefore, people with higher social support will experience less work‐home conflict.

We also propose that social support from work can help to reduce procrastination. Individuals sometimes procrastinate for a relief from stress (Lavoie & Pychyl, 2001 ; Wan et al., 2014 ). Social support is particularly important in this extraordinary context, because it can act as a “negativity buffer” (Bavik, Shaw, & Wang, 2020 ), helping workers cope with stress and focus on tasks. Moreover, previous research has shown that social support can lead to more commitment to the organization (Rousseau & Aubé, 2010 ). Thus, employees with higher social support tend to repay their organizations by concentrating more on their work (i.e., showing less procrastination) (Buunk et al., 1993 ). Altogether, we propose that:

Proposition 1: Employees who receive more social support from work will experience less procrastination, work‐home interference, and loneliness during the period of working from home, and, therefore, will report higher levels of performance and well‐being.

Autonomy is another important job resource in the remote work context. During home office days, individuals usually experience frequent role transitions (both work‐to‐home and home‐to‐work transitions), making the challenge of work‐home interference become more pronounced (Delanoeije et al., 2019 ). As participants stated, workflows during the regular working hours were frequently interrupted by demands from the family domain (e.g., taking care of children). In addition, some people were also expected to be “always online,” resulting in intrusions of unintended tasks or communications after hours (e.g., responding to client or supervisor needs). Job autonomy allows employees to decide when and how to accomplish their tasks. Thus, employees high on job autonomy can more effectively balance different responsibilities or demands across domains. Accordingly, we argue that:

Proposition 2: Employees with higher levels of job autonomy will experience less work‐home interference during the period of working from home, and, therefore, will have higher levels of performance and well‐being.

Based on our qualitative analyses, we argue that two demands—workload and monitoring—exert mixed effects on individuals. On the bright side, workload and monitoring can reduce workers’ procrastination. As summarized in Steel’s ( 2007 ) review, the timing of rewards and punishments predicts procrastination. Individuals are more likely to procrastinate if they can obtain immediate rewards with delayed punishments. In contrast, procrastination diminishes as punishments approached (e.g., deadline). Workload and monitoring are expected to decrease procrastination, because punishments would approach immediately if people cannot accomplish tasks in time or are found to be spending time on non‐work‐related issues at work.

On the negative side, workload and monitoring, acting as job demands, can easily invade individuals’ personal lives during home office days (Kossek et al., 2006 ; Lautsch et al., 2009 ). In other words, work‐related demands caused by workload and monitoring will hinder employees to fulfill their family responsibilities, which in turn eventually hurt their well‐being (Grant‐Vallone & Donaldson, 2001 ). Consequently, we propose that:

Proposition 3: (a) Employees with higher workload and those who are under more intensive monitoring will experience less procrastination during the period of working from home and, therefore, will have higher levels of performance; but (b) these employees will experience more work‐to‐home interference and, therefore, will have lower levels of well‐being.

We also propose that virtual work characteristics might not hold the same value for everyone. Specially, the effects of social support, monitoring, and workload on procrastination will be more significant for less‐disciplined individuals. That is because less‐disciplined people need external driving forces to “push” them (Steel, 2007 ). For people lacking discipline, social support can provide the psychological resources for self‐regulation (Pilcher & Bryant, 2016 ). Workload and monitoring, moreover, will increase the costs of procrastination, which motivate them to concentrate on their tasks to avoid potential punishments (Steel, 2007 ). In contrast, disciplined individuals can more effectively control their own behaviors and may not necessarily rely on external forces.

Proposition 4: The effects of social support, monitoring, and workload on procrastination will be stronger for less‐disciplined employees.

In the work place, informal interactions can simply “happen”; the so‐called “water cooler” effect (Fayard & Weeks, 2007 ). However, such interactions need to be more deliberately orchestrated when working from home. Individuals need to actively participate in such interactions, either by initiating them, or by consciously joining in to such an activity arranged by someone else. Given the unique nature of the social support in this context, we suspect that people need self‐discipline to utilize the social resources from work to reduce loneliness. That is, individuals low in self‐discipline are likely to be distracted by various temptations in cyberspace (O’Neill et al., 2014 ), and fail to consciously or proactively orchestrate and engage in informal communication activities. Hence, we propose that:

Proposition 5: The effects of social support on loneliness will be stronger for disciplined employees.

STUDY 2: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

Study 2 sample and procedure.

We recruited participants via www.wjx.cn , a Chinese online data collection platform that is similar to Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) and Prolific Academic. It has been widely used in previous studies conducted in the Chinese context (e.g., Buchtel et al., 2015 ; Lu et al., 2020 ). WJX has a large participant pool with 2.6 million participants from China, which allowed us to recruit niche samples on demand. We recruited participants who were working from home or had recently come back to the normal office‐based workplace after a period of working from home during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Like the pricing policy of Prolific Academic, monetary compensation was calculated by WJX based on the sample size, the length of the survey, and screening conditions. Following the quote from WJX, each participant was compensated 15 Chinese yuan (equivalent to about 2.1 US dollars).

Our final sample consisted of 522 participants, with 271 being female (51.9%). Participants were from a wide range of industries including IT (26.6%), education (15.5%), and manufacturing (12.5%). They were employed as managers, teachers, editors, engineers, and so forth. The average age of participants was 31.67 years old ( SD =6.09); 306 participants (58.6%) lived with their children; 161 participants (30.84%) held management positions; participants had worked from home for an average of 21.25 days ( SD =17.25); and they worked 7.02 hours per workday on average ( SD =1.98).

Study 2 Measures

Virtual work characteristics.

We used the four‐item scale adapted from Morgeson and Humphrey ( 2006 ) to measure social support whilst working at home. A sample item is “During the period of working from home, people I worked with were friendly.” Job autonomy was measured using the three‐item scale developed by Hackman and Oldham ( 1980 ), and a sample item is “During the period of working from home, I had considerable autonomy in determining how I did my job.” The average number of their daily working hours during the period of working from home was used as a relatively objective indicator to operationalize workload.

Based on interviews in Study 1, we developed a four‐item checklist to measure employees’ received monitoring during the period of working from home. Our scale covered three frequently mentioned techniques, that is, “providing daily reports,” “clocking in/out via APPs such as DingTalk,” and “keeping cameras switched on during working time”; the fourth item, “other methods to monitor my work performance during the period of working home,” was used to capture other potential techniques. Participants were asked to indicate whether their organizations/managers adopted these techniques to monitor employees’ work performance by checking “Yes” or “No.” The intensity of monitoring was calculated by summing the number of techniques adopted by their organizations/managers.

Self‐Discipline

Self‐discipline was measured by the three‐item scale adapted from Lindner et al. ( 2015 ). A sample item is “I am good at resisting temptation.”

Remote Work Challenges: Work‐Home Interference, Procrastination, Loneliness, and Communication Effectiveness

A six‐item scale developed by Carlson et al. ( 2000 ) was used to measure work‐to‐home interference (WHI; a sample item is “During the period of working from home, my work kept me from my family activities more than I would like”) and home‐to‐work interference (HWI; a sample item is “During the period of working from home, the time I spent on family responsibilities often interfered with my work responsibilities”).

We used the three‐item scale adapted from Tuckman ( 1991 ) to measure procrastination. A sample item is “During the period of working from home, I needlessly delayed finishing jobs, even when they were important.”

Loneliness during the period of working from home was captured by three items from the well‐established UCLA loneliness scale (Russell et al., 1980 ). Items are “I felt close to others” (reverse coded), “I did feel alone,” and “I felt isolated from others.”

Participants were asked to recall their experiences in virtual communications during the period of working from home, and a three‐item scale adapted from Lowry et al. ( 2009 ) was used to measure communication effectiveness. A sample item is “The time spent in virtual communications was efficiently used.”

Remote Worker Outcomes: Self‐Reported Performance and Well‐Being

We used a three‐item scale adapted from Williams and Anderson ( 1991 ) to measure task performance in remote working. A sample item is “During the period of working from home, I adequately completed my assigned duties.”

We also focused on two main well‐being outcomes, that is, emotional exhaustion and life satisfaction. Emotional exhaustion was captured by a two‐item scale adapted from Maslach and Jackson ( 1981 ). A sample item is “During the period of working from home, I felt emotionally drained from my work.” Life satisfaction was measured by a three‐item scale adapted from Diener et al. ( 1985 ). A sample item is “During the period of working from home, I was satisfied with my life.”

Previous studies have shown that age, gender, caring responsibility, and remote working experience can influence remote workers’ productivity and well‐being (e.g., Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ; Kossek et al., 2006 ; Martin & MacDonnell, 2012 ). Thus, we controlled for these variables while testing our proposed model. Specifically, gender was coded as a dummy variable (0 = male, 1 = female). Following Kossek et al. ( 2006 ), caring responsibility was coded as a dummy variable (0 = no caring responsibility, 1 = living with children). To assess remote worker experience, we asked participants to report the frequency of working from home before the lockdown with a 5‐point rating scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always . Finally, as our study was conducted in the COVID‐19 context, individuals’ psychological experience (e.g., life satisfaction) might be influenced by the pandemic. Hence, the severity of COVID ‐ 19 was controlled. We used the number of confirmed cases in each participant's city to indicate the severity of COVID‐19. To reduce the skewness of the severity distribution, we conducted a natural logarithmic transformation of the number of confirmed cases.

Study 2 Data Analysis

We estimated proposed relationships simultaneously in two path‐analytical models through Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). To examine the mediating effects (Propositions 1–4), we first estimated a path‐analytical model (Model 1) without self‐discipline as a moderator. Specifically, we regressed employee outcomes on all remote working challenges, virtual work characteristics, self‐discipline, and control variables. We also regressed remote working challenges (except for communication effectiveness) on all virtual work characteristics, self‐discipline, and control variables. To further examine the indirect effects of work design and self‐discipline on employees via remote working challenges, we used the Model Constraint command in Mplus to calculate the product of path coefficients a and b . Path coefficient a indicates the effect of the predictor on the mediator, while path coefficient b indicates the effect of the mediator on the outcome.

To examine the moderating effects of self‐discipline (Propositions 4 and 5), we estimated another path‐analytical model (Model 2) based on Model 1. Self‐discipline and virtual work characteristics were mean centered to generate the interaction terms.

We did not model the link between virtual work characteristics and communication effectiveness in the above model for two reasons. First, Study 1 did not suggest such a pathway. Second, even though prior research suggested some aspects of work design might be important for communication quality during remote working, these studies considered different work characteristics. For example, Marlow et al.’s ( 2017 ) theoretical framework suggested that interdependence and task complexity could influence communication in virtual teams; and Bélanger et al. ( 2013 ) found that technical support could shape teleworkers’ communication experiences. Instead, in our study, we controlled for the effects of communication effectiveness on performance and well‐being.

Study 2 Results

Table Table3 3 summarizes the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations among study variables.

Correlations of Study Variables

N = 515–522; Gender was coded as a dummy variable (0 = male, 1=female); With children was coded a dummy variable (0 = not, 1 = live with children); Management position was coded as dummy variable (0 = not, 1 = manager); The severity of COVID‐19 was measured by the natural logarithm of confirmed cases in participant's city; WHI =work‐to‐home interference; HWI =home‐to‐work interference.

Virtual Work Characteristics and Remote Working Challenges

The analysis showed that social support was the most powerful work design factor in terms of its breadth of impact. As shown in Table Table4, 4 , social support was negatively associated with procrastination, WHI, HWI, and loneliness. Job autonomy was negatively related to loneliness. Monitoring was positively related to WHI, but the relation between monitoring and procrastination was not significant, in contrast to what we expected from the interviews. The effects of workload on remote work experiences were mixed. Workload was negatively related to procrastination, but it was positively related to WHI.

Path Analysis Results for Testing Main Effects and Mediating Effects (Model 1)

N = 515. WHI =work‐to‐home interference; HWI =home‐to‐work interference; Standard error is indicated in bracket; Calculations are based on logarithmic values for workload (i.e., working hours).

Remote Working Challenges and Employee Outcomes

As shown in Table Table4, 4 , worker's performance was significantly influenced by procrastination and HWI. Emotional exhaustion was predicted by each remote working challenge, including procrastination, WHI, HWI, and loneliness. Finally, life satisfaction was negatively associated with WHI and loneliness.

Indirect Effects of Virtual Work Characteristics on Employee Outcomes via Remote Work Challenges

We further examined the indirect effects of virtual work characteristics on employee outcomes via remote working challenges using the Model Constraint command in Mplus . As shown in Table Table4, 4 , social support had a positive effect on performance via lower procrastination and HWI; social support had a negative effect on emotional exhaustion via lower procrastination, WHI, and loneliness; and social support had a positive effect on life satisfaction via lower WHI and loneliness. Thus, Proposition 1 was supported. Besides, WHI mediated the indirect effects of monitoring and workload on emotional exhaustion and life satisfaction and, therefore, Proposition 3(b) was supported.

Though Proposition 2 (i.e., job autonomy →work‐home interference →individual outcomes) was not supported, we found that loneliness mediated the indirect effects of job autonomy on emotional exhaustion and life satisfaction. Proposition 3(a) suggested the indirect effects of workload and monitoring on individuals via reducing procrastination, but this proposition was not supported by our data (Table (Table5 5 ).

Indirect Effects of Virtual Work Characteristics on Employee Outcomes via Remote Working Challenges

WHI =work‐to‐home interference; HWI =home‐to‐work interference; Indirect effects in bold were not significant with 95% CI.

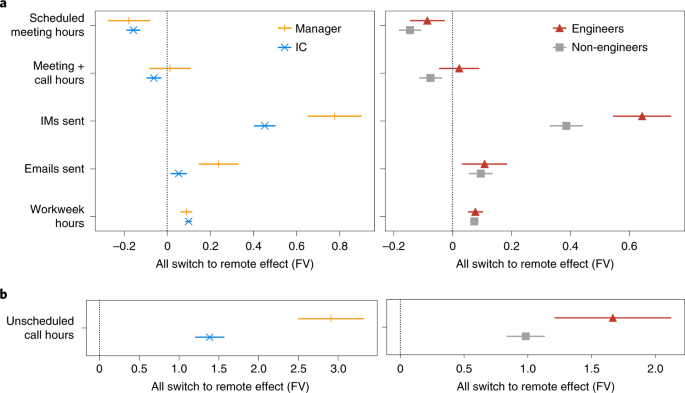

Moderating Effects of Self‐Discipline

As shown in Table Table6, 6 , the interaction term of social support and self‐discipline was positively associated with procrastination ( B = .10, SE = .05, p < .05). As shown in Figure Figure2, 2 , social support was negatively associated with procrastination when self‐discipline was low (simple slope = −.25, p < .001) but unrelated to procrastination when self‐discipline was high (simple slope = −.07, ns ). However, self‐discipline cannot moderate the effects of monitoring and workload on procrastination. Thus, Proposition 4 was partially supported.

Path Analysis Results for Testing Moderating Effects (Model 2)

N = 515. WHI = work‐to‐home interference; HWI = home‐to‐work interference; Standard error is indicated in brackets; Calculations are based on logarithmic values for workload (i.e., working hours).

The moderating role of self‐discipline on the relationship between social support and procrastination.

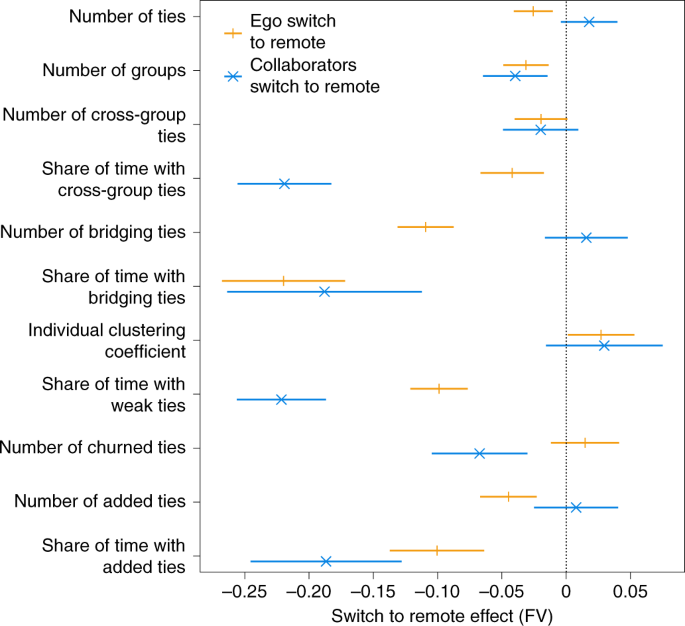

The relationship between social support and loneliness also depended on the extent of self‐discipline. The interaction term of social support and self‐discipline was negatively related to loneliness ( B = −.17, SE = .05, p < .001). As shown in Figure Figure3, 3 , social support was negatively associated with loneliness when self‐discipline was high (simple slope = −.34, p < .001) but unrelated to loneliness when self‐discipline was low (simple slope = −.06, ns ), indicating that the relationship between social support and loneliness was stronger for self‐disciplined workers. Thus, Proposition 5 was supported.

The moderating role of self‐discipline on the relationship between social support and loneliness.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 outbreak has created a unique context in which many employees were involuntarily required to work from home intensively, thus questioning the applicability of existing knowledge on remote working. Consequently, we argued that it is necessary to conduct exploratory research to identify the major challenges remote workers were struggling with in this unique context, and the role of virtual work characteristics in shaping these challenges. We discuss key implications of our findings next.

Work Characteristics as a Vehicle for Improving Remote Workers’ Experiences

Work design is one of the most influential theoretical perspectives in remote working literature. The current research identified that existing research has predominantly regarded remote work as an independent variable (e.g., remote work intensity) and investigated how work characteristics moderate or mediate the effects of remote work on individual outcomes. We argued that these two dominant approaches provide restricted insights for remote working practice during the COVID‐19 outbreak, because theoretical meanings and relationships may have been shaped or changed by the unique context (Johns, 2006). Thus, we advocate that it is theoretically and practically important to regard remote working during the pandemic as a context and explore/examine what virtual work characteristics really matter and how they matter (i.e., Approach 3).

Based on two studies conducted in this unique context, we identified four key remote work challenges (i.e., work‐home interference, ineffective communication, procrastination, and loneliness), as well as four virtual work characteristics that affected the experience of these challenges (i.e., social support, job autonomy, monitoring, and workload) and one key individual difference factor (i.e., workers’ self‐discipline). Generally, our findings are consistent with well‐established work design and remote working literature. Results from our two studies support the argument that virtual work characteristics can be, and are, a powerful vehicle for improving remote workers’ work effectiveness and well‐being. In particular, social support and job autonomy, acting as job resources, help employees to deal with challenges in remote working. Workload and monitoring, however, both functioned as demands, increasing remote workers’ work‐home interference, and thereby undermining employee well‐being.

Importantly, we also identified some findings that appear to be unique to the pandemic context. First, scholars and managers usually believe remote working can provide employees with autonomy to alleviate work‐family conflicts (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ). However, our research shows that remote workers were struggling with work‐home interference as a major challenge, and work‐home interference in this context cannot even be mitigated by job autonomy. Besides, procrastination has been framed as a trait‐like variable in remote working literature (Allen et al., 2015 ), and, therefore, managers tend to provide flexible work arrangements for individuals with greater abilities to avoid distractions. Our study shows that procrastination was one of the concrete challenges in remote working; more importantly, it can be mitigated by work characteristics (i.e., social support and workload).

In addition, the nuanced effects of work characteristics on individuals are unique in the pandemic context. The role of social support appears to have become much more pronounced during the pandemic. In other words, social support appears to be the most powerful virtual work characteristic because it had positive indirect impacts on performance and well‐being via its associated beneficial effects on all the identified challenges. Moreover, although job autonomy did not relate to work‐home interference as expected, it was conductive to reduce loneliness during the home office days, which was not a finding we hypothesized. Finally, self‐discipline emerged as an important moderating individual difference factor. Self‐discipline, however, has been largely omitted in previous remote work studies, most likely because flexible work arrangements are usually provided only to employees with higher self‐discipline. When people are required to work from home irrespective of their abilities and preferences, we find that self‐discipline can significantly shape remote working experiences.

Overall, the current research has gained contextually relevant insights by exploring how virtual work characteristics shape remote working experiences in the unique COVID‐19 outbreak context. We discuss these findings more deeply next.

Re‐Theorizing Home‐Work Conflict During Remote Work

To date, in the remote working literature, flexible work arrangements are predominantly framed as a useful policy for balancing work and personal life. That is, compared with these who have no opportunities to engage in flexible work, some degree of teleworking helps to reduce work‐family conflict (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ). These studies usually treat remote working as an independent variable, resulting in a natural confound because they focus on people who, largely, have chosen this form of working, perhaps because their potential for work‐home conflict is lower in the first place (that is, lower conflict means they prefer flexible working) or because they have the resources to be better able to balance work‐family conflict at home. However, when individuals do not choose remote working, as in our study, their lack of preference or resources to do so might mean that working from home creates a significant challenge. In other words, it is possible that previous research says more about the people who choose flexible working than it does about the real experience of working from home. However, the current research might question this conclusion. Framing remote working as a context, our qualitative analyses showed work‐home interference is the most frequently mentioned challenge in the home office, and its negative effects were shown in Study 2.

Our research shows that job autonomy did not predict work‐home interference as expected. Theoretically, we would expect job autonomy to be important for work‐home interference because autonomy gives people latitude to manage the demands in a flexible way (Kahn & Byosiere, 1992 ; Bakker, Demerouti, & Euwema, 2005 ). Empirical research also supports the positive role of job autonomy in the remote work context (e.g., Kossek et al., 2009 ). How to explain our finding? On the one hand, it might simply be that job autonomy is less important for managing home demands in a remote worker context in which everyone works from home, not just the elite few. On the other hand, it might also be due to the unique nature of home‐work conflict in this study. If some of the home‐work conflict is self‐induced because people cannot maintain home/work boundaries, we would not expect autonomy to be especially helpful. One might even then theorize that, in the pandemic context, autonomy might positively help manage home‐work stressors such as child‐care demands but might negatively affect home‐work boundary self‐management, with these countervailing forces explaining the weaker role of autonomy for home‐work conflict.

Finally, it is also possible our findings relate to the unusual context. We note that the mean for job autonomy in the sample was 4.03 (on a 5‐point scale), which is very high for Chinese workers who tend to usually have relatively lower levels of job autonomy (e.g., Xie, 1996 ). The high job autonomy might, in turn, reflect the unusual remote work situation in which workers had to very rapidly set up to work at home. Managers might not have had sufficient time to fully set up their “usual” controls. Thus, it is possible that in this case the level of job autonomy was artificially high, leading to a ceiling effect suppressing its impact. Further research is needed on this issue.

Although the autonomy findings were unexpected, it is perhaps not a surprise that monitoring and workload that are usually theorized as job demands at work, exerted negative impacts on employees’ home‐work conflicts in this remote work context. Our results show that individuals with higher levels of monitoring and workload reported greater WHI. While the positive relation between workload and work‐family conflict is consistent with the existing work‐family interface research, the finding that monitoring is also positively associated with work‐family conflict adds to the literature as a new form of work demands that leads to negative work‐family spillover.

Procrastination as a Challenge that Can Be Mitigated Through Work Design

Although procrastination has been acknowledged as an issue for remote workers in a recent review on telecommuting (Allen et al., 2015 ), to our knowledge, only one empirical study has considered this topic, and this study considered procrastination as a personality variable (O’Neill et al., 2014 ). In contrast, our qualitative and quantitative analyses led us to consider procrastination as a challenge as it can greatly hurt workers’ performance and cause emotional exhaustion.

Our findings showed that procrastination can be shaped by virtual work characteristics, and our results are different from those identified in normal contexts (Metin et al., 2016 ). Metin Taris and Peeters ( 2016 ) argued that employees high on job resources and demands will perceive less boredom at work, which in turn can reduce procrastination. Our findings are partially consistent with their study. Though the desirable effect of job autonomy on reducing procrastination was identified by Mentin et al. ( 2016 ), this effect was not supported in the current research. Social support is omitted in their research, but we find that remote workers who received more social support were less likely to procrastinate, and this association was stronger for less‐disciplined people. In other words, employees low in self‐discipline benefit more from social support in coping with procrastination in the home office.

The effect of workload on procrastination is consistent with Mentin et al.’s finding that employees with higher workload experience less procrastination (though the indirect effects of workload on performance and emotional exhaustion via procrastination were not supported). As for another major job demand in remote working, monitoring, its impact on reducing procrastination was frequently mentioned by participants in Study 1. However, results from Study 2 did not support this argument; instead, given the negative effects of monitoring on employee well‐being, it appears an unhelpful and potentially costly managerial practice.

As we argued above, the pandemic context has made some work characteristics pronounced, while others become less important. It is not surprising that we find these inconsistent results. In this unique context, our research reveals the importance of social support. Given that procrastination in the home office is a challenge for many, yet it hasn't been considered adequately in the remote working literature, we suggest the need for research to investigate the nuanced relationship between virtual work characteristics and procrastination, including boundary conditions (moving beyond self‐discipline in this research) and underlying mechanisms (Wan et al., 2014 ).

Loneliness and the Surprising Role of Job Autonomy

We identified the feeling of loneliness as an important challenge among remote workers during the pandemic. Earlier studies have identified a concern about professional isolation among remote workers because of the reduction in informal social interactions with colleagues in the home office (Cooper & Kurland, 2002 ). Advanced ICTs (e.g., WhatsApp) nowadays afford users the opportunity to engage in large‐scale and real‐time social interactions (McFarland & Ployhart, 2015 ), which potentially contributes to keeping people socially connected and overcoming isolation. However, our study shows that online social interactions are not necessarily sufficient for reducing loneliness; “a psychological pain of perceived relational deficiencies in the workplace” (Ozcelik & Barsade, 2018 ; Wright & Silard, 2020 ). As our participants indicated in Study 1, they were not satisfied with the quality of online social interactions due to restricted “intimacy” and “closeness,” and such a feature might relate to loneliness.

We find a somewhat surprising link between job autonomy and loneliness. The idea that virtual social interactions require some degree of self‐initiation may help to explain this association. That is, social interactions in the remote working context cannot simply “happen”; instead, individuals need to proactively initiate or engage in online interactions. Previous theory and research argues that job autonomy is crucial for fueling proactive behavior because autonomy enhances people's internalized motivation, builds their self‐confidence, and fosters activated positive affect; all of which can drive proactive behavior (e.g., Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, 2010 ). For example, being proactive involves some degree of interpersonal risk because it means self‐initiating a behavior that no one has instructed one to do, which heightens the need for individual self‐efficacy. Considerable research shows the role of job autonomy for enhancing employees’ self‐efficacy, and thereby increasing their proactive behaviors (e.g., Ohly & Fritz, 2009 ; Parker et al., 2006 ). Although the focus of the current study is on proactive behavior that is socially oriented, it is possible that job autonomy is important for building individuals’ proactive motivation to self‐initiate contact with others, and thereby reduce feelings of loneliness.

Communication Quality Beyond its Remote Attributes

A fourth observation regarding working from home challenges concerns the quality of communication, which was identified as a key challenge in the interview study. Although remote working literature has acknowledged the limitations of ICT‐mediated communication and has assumed it is a hindrance relative to face‐to‐face interaction (Raghuram et al., 2019 ), poor communication experience in virtual collaboration has been empirically addressed mainly in virtual team and computer‐mediated communication literature (e.g., Chang et al., 2014 ) rather than the literature on remote working. This situation might be because ICT‐related communication experience is logically related to the technical system at work (Bélanger et al., 2013 ; Dennis, Fuller, & Valacich, 2008 ), which is not the primary research focus in remote working literature. However, our study suggests such an omission is problematic because many interpersonal processes are mediated by ICTs in the current digital workplace (Wang et al., 2020 ), and, therefore, communication quality is an important experience to consider for remote workers. Poor communication will not only hinder performance, as suggested in our research, but can also impair professional relationships (Camacho et al., 2018 ) and increase work stress (Day et al., 2012 ). Thus, our findings inspire scholars and practitioners to re‐think how to facilitate high quality virtual communications for remote workers.

The Power of Self‐Discipline

As an attribute that helps remote workers to mitigate the destructive effects of interruptions, self‐discipline has been widely considered as an important and necessary skill for achieving remote working effectiveness (e.g., Haddon & Lewis, 1994 ; Kinsman, 1987 ). However, largely due to the fact that remote working has always been a luxury among a small proportion of workers, as we mentioned earlier, self‐discipline as a desirable attribute was more used merely as a criterion to select the right people as remote workers (Baruch, 2000 ). This, on the one hand, might have rendered most remote workers to be those having relatively higher levels of self‐discipline, possibly leading to people's limited understanding as to the broader influences of self‐discipline; and, on the other hand, might have downplayed the role of self‐discipline in remote working (i.e., it should not be merely used as a selection criterion).

In a context wherein remote working becomes the normal and everyone started working remotely, self‐discipline is no longer just a selection criterion but becomes something that every remote worker strives to gain or improve on. By showing the moderating role of self‐discipline in the relationship between virtual work characteristics and experienced challenges in remote working, this research underscored the critical role of self‐discipline among all individuals practicing remote working. We believe this finding is critical as it may greatly enhance remote working practitioners’ awareness of the importance of self‐discipline and may also motivate many remote workers to try to develop their self‐discipline to achieve work effectiveness and well‐being.

Practical Implications

Insights from working at home during COVID‐19 can, beyond the immediate context of the pandemic, guide flexible work practice after crisis. Here, we distill three lessons for managers and employees in future practice.

First, our findings can help organizations and managers to manage remote work effectively. The predominantly positive view of remote working in the literature to date might make managers ignore the need to consider how flexible workers jobs are designed. As Baruch ( 2000 ) articulated, organizations and managers should “find new ways to manage…, develop innovative career paths, and put in place proper support mechanisms for teleworkers” (p. 46). The current research revealed the crucial role of virtual work characteristics. Although further research is needed, our study suggests managers can boost remote workers’ productivity and well‐being via designing high‐quality remote work. The work design perspective can guide managers to design a better job for remote workers during the pandemic or even in future flexible work practices. For example, managers might incur a lot of cost in setting up monitoring systems (Groen et al., 2018 ), but the desirable effect of monitoring on work effectiveness was not supported by our data. Managers should instead engage more supportive management practices especially in this extraordinary context, such as communicating with subordinates using motivating language (Madlock, 2013 ), building trust within the distributed team (Grant et al., 2013 ), and sharing information rather than close monitoring (Lautsch et al., 2009 ).

Second, employees and managers should be aware of the challenges in practicing remote work. Remote working is attractive to organizations and individuals in the current digital age, because of space savings, the opportunity to utilize a global labor market, less time spent on commuting, and so forth (Baruch, 2000 ). Many commentators are speculating that remote working will become even more attractive after COVID‐19 (Hern, 2020 ). However, scholars and practitioners might overstate the bright side of remote working, especially if they rely on the established research. For example, our research indicated less‐disciplined people experienced more challenges while working from home and, therefore, teleworking may not be suitable for them. Given that such challenges will influence individuals’ performance and well‐being, employees and employers need to consider the fit between flexible work arrangements and the person (Golden et al., 2006 ; Perry et al., 2018 ).

Finally, a work design perspective potentially helps individuals to cope with challenges in remote working. In addition to the top‐down approach (i.e., re‐designing remote work), individuals can proactively craft their jobs (Tims & Bakker, 2010 ; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001 ; Zhang & Parker, 2019 ). For instance, engaging in informal communication with colleagues in a high‐intensity telecommuting setting has been shown to be positively related to job satisfaction (Fay & Kline, 2011 ). Thus, remote workers can proactively utilize current advanced enterprise social media (e.g., Slack) to socialize with others in an informal manner to overcome loneliness.

Limitations and Future Research

Our research inevitably has limitations. First, our qualitative and quantitative data were both collected in China, which may raise concerns about generalizability. Remote working in China and other developing countries is relatively new, which means we can capture individuals’ unique experiences during the sudden transition from the onsite office to home. However, one's remote work experience and acceptance of remote working can influence the impact of working from home (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007 ). Thus, it will be interesting to compare remote working during the pandemic between developing countries and developed countries in which flexible work arrangements are more widespread (e.g., exploring differences in coping strategies and perceived challenges). Our findings might also be influenced by cultural factors. For example, participants in Study 1 mentioned the necessity of monitoring in remote working, which might not generalize across countries. Although limited empirical work has examined the potential influences of national culture on individuals’ attitudes toward workplace electronic monitoring (see Ravid et al., 2019 for a systematic review), Panina and Aiello ( 2005 ) proposed a theoretical model that emphasized how cultural factors (e.g., individualism‐collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and power distance) are likely to mitigate the acceptance of electronic monitoring. Accordingly, cross‐cultural studies are needed to explore the generalizability of these findings, as well as how cultural factors shape the impacts of virtual work characteristics on remote worker outcomes.

Second, our research was conducted in an extraordinary context. This was to some extent the point of our research—the COVID‐19 outbreak provides a unique opportunity to address theoretical gaps and expand theory. This context provides extra pressure for employees, such as worry about the pandemic, social isolation, financial pressure, greater family interferences, and the like, which likely shaped the findings. Despite this difference in context, we believe our approach and findings will be important in future remote working research and practice. Sytch and Greer (2020) argued that the post‐pandemic work will be hybrid, that is, remote work will be more prevalent in the future. Indeed, Facebook and Twitter have announced that their employees can choose to work from home “forever” after the pandemic. Thus, future research still need to consider people's experiences at home versus the office. We see particular value in examining people's virtual work characteristics (when working remotely) as well as their work characteristics when working at home, and using these two sets of assessments to really understand people's holistic work experiences.

Finally, the cross‐sectional nature of Study 2 means it suffers from common method bias (CMB; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003 ) and the possibility of reverse causality, which means that we were unable to establish causality in this study. Considering this limitation, we recommend the use of longitudinal or experimental research designs in future research. A longitudinal design will also contribute to tracking dynamic processes, such as how individuals adapt to flexible work arrangements. In particular, given that working from home is becoming a day‐to‐day practice in many organizations, we recommend future researchers conduct daily diary studies to investigate the intraindividual processes of remote working. For example, it will be interesting to examine the antecedents and consequences of the remote working challenges identified in the current research on a daily basis. Future research also can benefit from collecting data from multiple sources. For example, although individuals themselves might be the more suitable raters for their own challenges, their work effectiveness and well‐being can be usefully assessed by their supervisors and spouses, respectively, to alleviate issues of common method bias.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX A.

Interview protocol.

Can you describe your work, life, or general psychological experiences during the period of working from home?

- Positive aspects (e.g., collaborations, personal life, emotion, etc.)

- Negative aspects