- University of Pennsylvania

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Penn Calendar

Search form

Evaluation Criteria for Formal Essays

Katherine milligan.

Please note that these four categories are interdependent. For example, if your evidence is weak, this will almost certainly affect the quality of your argument and organization. Likewise, if you have difficulty with syntax, it is to be expected that your transitions will suffer. In revision, therefore, take a holistic approach to improving your essay, rather than focussing exclusively on one aspect.

An excellent paper:

Argument: The paper knows what it wants to say and why it wants to say it. It goes beyond pointing out comparisons to using them to change the reader?s vision. Organization: Every paragraph supports the main argument in a coherent way, and clear transitions point out why each new paragraph follows the previous one. Evidence: Concrete examples from texts support general points about how those texts work. The paper provides the source and significance of each piece of evidence. Mechanics: The paper uses correct spelling and punctuation. In short, it generally exhibits a good command of academic prose.

A mediocre paper:

Argument: The paper replaces an argument with a topic, giving a series of related observations without suggesting a logic for their presentation or a reason for presenting them. Organization: The observations of the paper are listed rather than organized. Often, this is a symptom of a problem in argument, as the framing of the paper has not provided a path for evidence to follow. Evidence: The paper offers very little concrete evidence, instead relying on plot summary or generalities to talk about a text. If concrete evidence is present, its origin or significance is not clear. Mechanics: The paper contains frequent errors in syntax, agreement, pronoun reference, and/or punctuation.

An appallingly bad paper:

Argument: The paper lacks even a consistent topic, providing a series of largely unrelated observations. Organization: The observations are listed rather than organized, and some of them do not appear to belong in the paper at all. Both paper and paragraphs lack coherence. Evidence: The paper offers no concrete evidence from the texts or misuses a little evidence. Mechanics: The paper contains constant and glaring errors in syntax, agreement, reference, spelling, and/or punctuation.

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1916 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,380 quotes across 1916 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Writing a great essay

This resource covers key considerations when writing an essay.

While reading a student’s essay, markers will ask themselves questions such as:

- Does this essay directly address the set task?

- Does it present a strong, supported position?

- Does it use relevant sources appropriately?

- Is the expression clear, and the style appropriate?

- Is the essay organised coherently? Is there a clear introduction, body and conclusion?

You can use these questions to reflect on your own writing. Here are six top tips to help you address these criteria.

1. Analyse the question

Student essays are responses to specific questions. As an essay must address the question directly, your first step should be to analyse the question. Make sure you know exactly what is being asked of you.

Generally, essay questions contain three component parts:

- Content terms: Key concepts that are specific to the task

- Limiting terms: The scope that the topic focuses on

- Directive terms: What you need to do in relation to the content, e.g. discuss, analyse, define, compare, evaluate.

Look at the following essay question:

Discuss the importance of light in Gothic architecture.

- Content terms: Gothic architecture

- Limiting terms: the importance of light. If you discussed some other feature of Gothic architecture, for example spires or arches, you would be deviating from what is required. This essay question is limited to a discussion of light. Likewise, it asks you to write about the importance of light – not, for example, to discuss how light enters Gothic churches.

- Directive term: discuss. This term asks you to take a broad approach to the variety of ways in which light may be important for Gothic architecture. You should introduce and consider different ideas and opinions that you have met in academic literature on this topic, citing them appropriately .

For a more complex question, you can highlight the key words and break it down into a series of sub-questions to make sure you answer all parts of the task. Consider the following question (from Arts):

To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?

The key words here are American Revolution and revolution ‘from below’. This is a view that you would need to respond to in this essay. This response must focus on the aims and motivations of working people in the revolution, as stated in the second question.

2. Define your argument

As you plan and prepare to write the essay, you must consider what your argument is going to be. This means taking an informed position or point of view on the topic presented in the question, then defining and presenting a specific argument.

Consider these two argument statements:

The architectural use of light in Gothic cathedrals physically embodied the significance of light in medieval theology.

In the Gothic cathedral of Cologne, light served to accentuate the authority and ritual centrality of the priest.

Statements like these define an essay’s argument. They give coherence by providing an overarching theme and position towards which the entire essay is directed.

3. Use evidence, reasoning and scholarship

To convince your audience of your argument, you must use evidence and reasoning, which involves referring to and evaluating relevant scholarship.

- Evidence provides concrete information to support your claim. It typically consists of specific examples, facts, quotations, statistics and illustrations.

- Reasoning connects the evidence to your argument. Rather than citing evidence like a shopping list, you need to evaluate the evidence and show how it supports your argument.

- Scholarship is used to show how your argument relates to what has been written on the topic (citing specific works). Scholarship can be used as part of your evidence and reasoning to support your argument.

4. Organise a coherent essay

An essay has three basic components - introduction, body and conclusion.

The purpose of an introduction is to introduce your essay. It typically presents information in the following order:

- A general statement about the topic that provides context for your argument

- A thesis statement showing your argument. You can use explicit lead-ins, such as ‘This essay argues that...’

- A ‘road map’ of the essay, telling the reader how it is going to present and develop your argument.

Example introduction

"To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?"

Introduction*

Historians generally concentrate on the twenty-year period between 1763 and 1783 as the period which constitutes the American Revolution [This sentence sets the general context of the period] . However, when considering the involvement of working people, or people from below, in the revolution it is important to make a distinction between the pre-revolutionary period 1763-1774 and the revolutionary period 1774-1788, marked by the establishment of the continental Congress(1) [This sentence defines the key term from below and gives more context to the argument that follows] . This paper will argue that the nature and aims of the actions of working people are difficult to assess as it changed according to each phase [This is the thesis statement] . The pre-revolutionary period was characterised by opposition to Britain’s authority. During this period the aims and actions of the working people were more conservative as they responded to grievances related to taxes and scarce land, issues which directly affected them. However, examination of activities such as the organisation of crowd action and town meetings, pamphlet writing, formal communications to Britain of American grievances and physical action in the streets, demonstrates that their aims and actions became more revolutionary after 1775 [These sentences give the ‘road map’ or overview of the content of the essay] .

The body of the essay develops and elaborates your argument. It does this by presenting a reasoned case supported by evidence from relevant scholarship. Its shape corresponds to the overview that you provided in your introduction.

The body of your essay should be written in paragraphs. Each body paragraph should develop one main idea that supports your argument. To learn how to structure a paragraph, look at the page developing clarity and focus in academic writing .

Your conclusion should not offer any new material. Your evidence and argumentation should have been made clear to the reader in the body of the essay.

Use the conclusion to briefly restate the main argumentative position and provide a short summary of the themes discussed. In addition, also consider telling your reader:

- What the significance of your findings, or the implications of your conclusion, might be

- Whether there are other factors which need to be looked at, but which were outside the scope of the essay

- How your topic links to the wider context (‘bigger picture’) in your discipline.

Do not simply repeat yourself in this section. A conclusion which merely summarises is repetitive and reduces the impact of your paper.

Example conclusion

Conclusion*.

Although, to a large extent, the working class were mainly those in the forefront of crowd action and they also led the revolts against wealthy plantation farmers, the American Revolution was not a class struggle [This is a statement of the concluding position of the essay]. Working people participated because the issues directly affected them – the threat posed by powerful landowners and the tyranny Britain represented. Whereas the aims and actions of the working classes were more concerned with resistance to British rule during the pre-revolutionary period, they became more revolutionary in nature after 1775 when the tension with Britain escalated [These sentences restate the key argument]. With this shift, a change in ideas occurred. In terms of considering the Revolution as a whole range of activities such as organising riots, communicating to Britain, attendance at town hall meetings and pamphlet writing, a difficulty emerges in that all classes were involved. Therefore, it is impossible to assess the extent to which a single group such as working people contributed to the American Revolution [These sentences give final thoughts on the topic].

5. Write clearly

An essay that makes good, evidence-supported points will only receive a high grade if it is written clearly. Clarity is produced through careful revision and editing, which can turn a good essay into an excellent one.

When you edit your essay, try to view it with fresh eyes – almost as if someone else had written it.

Ask yourself the following questions:

Overall structure

- Have you clearly stated your argument in your introduction?

- Does the actual structure correspond to the ‘road map’ set out in your introduction?

- Have you clearly indicated how your main points support your argument?

- Have you clearly signposted the transitions between each of your main points for your reader?

- Does each paragraph introduce one main idea?

- Does every sentence in the paragraph support that main idea?

- Does each paragraph display relevant evidence and reasoning?

- Does each paragraph logically follow on from the one before it?

- Is each sentence grammatically complete?

- Is the spelling correct?

- Is the link between sentences clear to your readers?

- Have you avoided redundancy and repetition?

See more about editing on our editing your writing page.

6. Cite sources and evidence

Finally, check your citations to make sure that they are accurate and complete. Some faculties require you to use a specific citation style (e.g. APA) while others may allow you to choose a preferred one. Whatever style you use, you must follow its guidelines correctly and consistently. You can use Recite, the University of Melbourne style guide, to check your citations.

Further resources

- Germov, J. (2011). Get great marks for your essays, reports and presentations (3rd ed.). NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Using English for Academic Purposes: A guide for students in Higher Education [online]. Retrieved January 2020 from http://www.uefap.com

- Williams, J.M. & Colomb, G. G. (2010) Style: Lessons in clarity and grace. 10th ed. New York: Longman.

* Example introduction and conclusion adapted from a student paper.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

English Composition 1

Evaluation and grading criteria for essays.

IVCC's online Style Book presents the Grading Criteria for Writing Assignments .

This page explains some of the major aspects of an essay that are given special attention when the essay is evaluated.

Thesis and Thesis Statement

Probably the most important sentence in an essay is the thesis statement, which is a sentence that conveys the thesis—the main point and purpose of the essay. The thesis is what gives an essay a purpose and a point, and, in a well-focused essay, every part of the essay helps the writer develop and support the thesis in some way.

The thesis should be stated in your introduction as one complete sentence that

- identifies the topic of the essay,

- states the main points developed in the essay,

- clarifies how all of the main points are logically related, and

- conveys the purpose of the essay.

In high school, students often are told to begin an introduction with a thesis statement and then to follow this statement with a series of sentences, each sentence presenting one of the main points or claims of the essay. While this approach probably helps students organize their essays, spreading a thesis statement over several sentences in the introduction usually is not effective. For one thing, it can lead to an essay that develops several points but does not make meaningful or clear connections among the different ideas.

If you can state all of your main points logically in just one sentence, then all of those points should come together logically in just one essay. When I evaluate an essay, I look specifically for a one-sentence statement of the thesis in the introduction that, again, identifies the topic of the essay, states all of the main points, clarifies how those points are logically related, and conveys the purpose of the essay.

If you are used to using the high school model to present the thesis of an essay, you might wonder what you should do with the rest of your introduction once you start presenting a one-sentence statement of your thesis. Well, an introduction should do two important things: (1) present the thesis statement, and (2) get readers interested in the subject of the essay.

Instead of outlining each stage of an essay with separate sentences in the introduction, you could draw readers into your essay by appealing to their interests at the very beginning of your essay. Why should what you discuss in your essay be important to readers? Why should they care? Answering these questions might help you discover a way to draw readers into your essay effectively. Once you appeal to the interests of your readers, you should then present a clear and focused thesis statement. (And thesis statements most often appear at the ends of introductions, not at the beginnings.)

Coming up with a thesis statement during the early stages of the writing process is difficult. You might instead begin by deciding on three or four related claims or ideas that you think you could prove in your essay. Think in terms of paragraphs: choose claims that you think could be supported and developed well in one body paragraph each. Once you have decided on the three or four main claims and how they are logically related, you can bring them together into a one-sentence thesis statement.

All of the topic sentences in a short paper, when "added" together, should give us the thesis statement for the entire paper. Do the addition for your own papers, and see if you come up with the following:

Topic Sentence 1 + Topic Sentence 2 + Topic Sentence 3 = Thesis Statement

Organization

Effective expository papers generally are well organized and unified, in part because of fairly rigid guidelines that writers follow and that you should try to follow in your papers.

Each body paragraph of your paper should begin with a topic sentence, a statement of the main point of the paragraph. Just as a thesis statement conveys the main point of an entire essay, a topic sentence conveys the main point of a single body paragraph. As illustrated above, a clear and logical relationship should exist between the topic sentences of a paper and the thesis statement.

If the purpose of a paragraph is to persuade readers, the topic sentence should present a claim, or something that you can prove with specific evidence. If you begin a body paragraph with a claim, a point to prove, then you know exactly what you will do in the rest of the paragraph: prove the claim. You also know when to end the paragraph: when you think you have convinced readers that your claim is valid and well supported.

If you begin a body paragraph with a fact, though, something that it true by definition, then you have nothing to prove from the beginning of the paragraph, possibly causing you to wander from point to point in the paragraph. The claim at the beginning of a body paragraph is very important: it gives you a point to prove, helping you unify the paragraph and helping you decide when to end one paragraph and begin another.

The length and number of body paragraphs in an essay is another thing to consider. In general, each body paragraph should be at least half of a page long (for a double-spaced essay), and most expository essays have at least three body paragraph each (for a total of at least five paragraphs, including the introduction and conclusion.)

Support and Development of Ideas

The main difference between a convincing, insightful interpretation or argument and a weak interpretation or argument often is the amount of evidence than the writer uses. "Evidence" refers to specific facts.

Remember this fact: your interpretation or argument will be weak unless it is well supported with specific evidence. This means that, for every claim you present, you need to support it with at least several different pieces of specific evidence. Often, students will present potentially insightful comments, but the comments are not supported or developed with specific evidence. When you come up with an insightful idea, you are most likely basing that idea on some specific facts. To present your interpretation or argument well, you need to state your interpretation and then explain the facts that have led you to this conclusion.

Effective organization is also important here. If you begin each body paragraph with a claim, and if you then stay focused on supporting that claim with several pieces of evidence, you should have a well-supported and well-developed interpretation.

As stated above, each body paragraph generally should be at least half of a page long, so, if you find that your body paragraphs are shorter than this, then you might not be developing your ideas in much depth. Often, when a student has trouble reaching the required minimum length for an essay, the problem is the lack of sufficient supporting evidence.

In an interpretation or argument, you are trying to explain and prove something about your subject, so you need to use plenty of specific evidence as support. A good approach to supporting an interpretation or argument is dividing your interpretation or argument into a few significant and related claims and then supporting each claim thoroughly in one body paragraph.

Insight into Subject

Sometimes a student will write a well-organized essay, but the essay does not shed much light on the subject. At the same time, I am often amazed at the insightful interpretations and arguments that students come up with. Every semester, students interpret aspects of texts or present arguments that I had never considered.

If you are writing an interpretation, you should reread the text or study your subject thoroughly, doing your best to notice something new each time you examine it. As you come up with a possible interpretation to develop in an essay, you should re-examine your subject with that interpretation in mind, marking passages (if your subject is a literary text) and taking plenty of notes on your subject. Studying your subject in this way will make it easier for you to find supporting evidence for your interpretation as you write your essay.

The insightfulness of an essay often is directly related to the organization and the support and development of the ideas in the essay. If you have well-developed body paragraphs focused on one specific point each, then it is likely that you are going into depth with the ideas you present and are offering an insightful interpretation.

If you organize your essay well, and if you use plenty of specific evidence to support your thesis and the individual claims that comprise that thesis, then there is a good possibility that your essay will be insightful.

Clarity is always important: if your writing is not clear, your meaning will not reach readers the way you would like it to. According to IVCC's Grading Criteria for Writing Assignments , "A," "B," and "C" essays are clear throughout, meaning that problems with clarity can have a substantial effect on the grade of an essay.

If any parts of your essay or any sentences seem just a little unclear to you, you can bet that they will be unclear to readers. Review your essay carefully and change any parts of the essay that could cause confusion for readers. Also, take special note of any passages that your peer critiquers feel are not very clear.

"Style" refers to the kinds of words and sentences that you use, but there are many aspects of style to consider. Aspects of style include conciseness, variety of sentence structure, consistent verb tense, avoidance of the passive voice, and attention to the connotative meanings of words.

Several of the course web pages provide information relevant to style, including the following pages:

- "Words, Words, Words"

- Using Specific and Concrete Diction

- Integrating Quotations into Sentences

- Formal Writing Voice

William Strunk, Jr.'s, The Elements of Style is a classic text on style that is now available online.

Given the subject, purpose, and audience for each essay in this course, you should use a formal writing voice . This means that you should avoid use of the first person ("I," "me," "we," etc.), the use of contractions ("can't," "won't," etc.), and the use of slang or other informal language. A formal writing voice will make you sound more convincing and more authoritative.

If you use quotations in a paper, integrating those quotations smoothly, logically, and grammatically into your own sentences is important, so make sure that you are familiar with the information on the Integrating Quotations into Sentences page.

"Mechanics" refers to the correctness of a paper: complete sentences, correct punctuation, accurate word choice, etc. All of your papers for the course should be free or almost free from errors. Proofread carefully, and consider any constructive comments you receive during peer critiques that relate to the "mechanics" of your writing.

You might use the grammar checker if your word-processing program has one, but grammar checkers are correct only about half of the time. A grammar checker, though, could help you identify parts of the essay that might include errors. You will then need to decide for yourself if the grammar checker is right or wrong.

The elimination of errors from your writing is important. In fact, according to IVCC's Grading Criteria for Writing Assignments , "A," "B," and "C" essays contain almost no errors. Significant or numerous errors are a characteristic of a "D" or "F" essay.

Again, the specific errors listed in the second table above are explained on the Identifying and Eliminating Common Errors in Writing web page.

You should have a good understanding of what errors to look out for based on the feedback you receive on graded papers, and I would be happy to answer any questions you might have about possible errors or about any other aspects of your essay. You just need to ask!

Copyright Randy Rambo , 2021.

Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

Asking analytical questions, introductions, what do introductions across the disciplines have in common, anatomy of a body paragraph, transitions, tips for organizing your essay, counterargument, conclusions.

Essay Rubric: Basic Guidelines and Sample Template

11 December 2023

last updated

Lectures and tutors provide specific requirements for students to meet when writing essays. Basically, an essay rubric helps tutors to analyze the quality of articles written by students. In this case, useful rubrics make the analysis process simple for lecturers as they focus on specific concepts related to the writing process. Also, an essay rubric list and organize all of the criteria into one convenient paper. In other instances, students use an essay rubric to enhance their writing skills by examining various requirements. Then, different types of essay rubrics vary from one educational level to another. For example, Master’s and Ph.D. essay rubrics focus on examining complex thesis statements and other writing mechanics. However, high school essay rubrics examine basic writing concepts. In turn, a sample template of a high school rubric in this article can help students to evaluate their papers before submitting them to their teachers.

General Aspects of an Essay Rubric

An essay rubric refers to the way how teachers assess student’s composition writing skills and abilities. Basically, an essay rubric provides specific criteria to grade assignments. In this case, teachers use essay rubrics to save time when evaluating and grading various papers. Hence, learners must use an essay rubric effectively to achieve desired goals and grades.

General Assessment Table for an Essay Rubric

1. organization.

Excellent/8 points: The essay contains stiff topic sentences and a controlled organization.

Very Good/6 points: The essay contains a logical and appropriate organization. The writer uses clear topic sentences.

Average/4 points: The essay contains a logical and appropriate organization. The writer uses clear topic sentences.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The essay has an inconsistent organization.

Unacceptable/0 points: The essay shows the absence of a planned organization.

Grade: ___ .

Excellent/8 points: The essay shows the absence of a planned organization.

Very Good/6 points: The paper contains precise and varied sentence structures and word choices.

Average/4 points: The paper follows a limited but mostly correct sentence structure. There are different sentence structures and word choices.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The paper contains several awkward and unclear sentences. There are some problems with word choices.

Unacceptable/0 points: The writer does not contain apparent control over sentence structures and word choice.

Excellent/8 points: The content appears sophisticated and contains well-developed ideas.

Very Good/6 points: The essay content appears illustrative and balanced.

Average/4 points: The essay contains unbalanced content that requires more analysis.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The essay contains a lot of research information without analysis or commentary.

Unacceptable/0 points: The essay lacks relevant content and does not fit the thesis statement . Essay rubric rules are not followed.

Excellent/8 points: The essay contains a clearly stated and focused thesis statement.

Very Good/6 points: The written piece comprises a clearly stated argument. However, the focus would have been sharper.

Average/4 points: The thesis phrasing sounds simple and lacks complexity. The writer does not word the thesis correctly.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The thesis statement requires a clear objective and does not fit the theme in the content of the essay.

Unacceptable/0 points: The thesis is not evident in the introduction.

Excellent/8 points: The essay is clear and focused. The work holds the reader’s attention. Besides, the relevant details and quotes enrich the thesis statement.

Very Good/6 points: The essay is mostly focused and contains a few useful details and quotes.

Average/4 points: The writer begins the work by defining the topic. However, the development of ideas appears general.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The author fails to define the topic well, or the writer focuses on several issues.

Unacceptable/0 points: The essay lacks a clear sense of a purpose or thesis statement. Readers have to make suggestions based on sketchy or missing ideas to understand the intended meaning. Essay rubric requirements are missed.

6. Sentence Fluency

Excellent/8 points: The essay has a natural flow, rhythm, and cadence. The sentences are well built and have a wide-ranging and robust structure that enhances reading.

Very Good/6 points: The ideas mostly flow and motivate a compelling reading.

Average/4 points: The text hums along with a balanced beat but tends to be more businesslike than musical. Besides, the flow of ideas tends to become more mechanical than fluid.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The essay appears irregular and hard to read.

Unacceptable/0 points: Readers have to go through the essay several times to give this paper a fair interpretive reading.

7. Conventions

Excellent/8 points: The student demonstrates proper use of standard writing conventions, like spelling, punctuation, capitalization, grammar, usage, and paragraphing. The student uses protocols in a way that improves the readability of the essay.

Very Good/6 points: The student demonstrates proper writing conventions and uses them correctly. One can read the essay with ease, and errors are rare. Few touch-ups can make the composition ready for publishing.

Average/4 points: The writer shows reasonable control over a short range of standard writing rules. The writer handles all the conventions and enhances readability. The errors in the essay tend to distract and impair legibility.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The writer makes an effort to use various conventions, including spelling, punctuation, capitalization, grammar usage, and paragraphing. The essay contains multiple errors.

Unacceptable/0 points: The author makes repetitive errors in spelling, punctuation, capitalization, grammar, usage, and paragraphing. Some mistakes distract readers and make it hard to understand the concepts. Essay rubric rules are not covered.

8. Presentation

Excellent/8 points: The form and presentation of the text enhance the readability of the essay and the flow of ideas.

Very Good/6 points: The format has few mistakes and is easy to read.

Average/4 points: The writer’s message is understandable in this format.

Needs Improvement/2 points: The writer’s message is only comprehensible infrequently, and the paper appears disorganized.

Unacceptable/0 points: Readers receive a distorted message due to difficulties connecting to the presentation of the text.

Final Grade: ___ .

Grading Scheme for an Essay Rubric:

- A+ = 60+ points

- A = 55-59 points

- A- = 50-54 points

- B+ = 45-49 points

- B = 40-44 points

- B- = 35-39 points

- C+ = 30-34 points

- C = 25-29 points

- C- = 20-24 points

- D = 10-19 points

- F = less than 9 points

Basic Differences in Education Levels and Essay Rubrics

The quality of essays changes at different education levels. For instance, college students must write miscellaneous papers when compared to high school learners. In this case, an essay rubric will change for these different education levels. For example, university and college essays should have a debatable thesis statement with varying points of view. However, high school essays should have simple phrases as thesis statements. Then, other requirements in an essay rubric will be more straightforward for high school students. For master’s and Ph.D. essays, the criteria presented in an essay rubric should focus on examining the paper’s complexity. In turn, compositions for these two categories should have thesis statements that demonstrate a detailed analysis of defined topics that advance knowledge in a specific area of study.

Summing Up on an Essay Rubric

Essay rubrics help teachers, instructors, professors, and tutors to analyze the quality of essays written by students. Basically, an essay rubric makes the analysis process simple for lecturers. Essay rubrics list and organize all of the criteria into one convenient paper. In other instances, students use the essay rubrics to improve their writing skills. However, they vary from one educational level to the other. Master’s and Ph.D. essay rubrics focus on examining complex thesis statements and other writing mechanics. However, high school essay rubrics examine basic writing concepts. The following are some of the tips that one must consider when preparing a rubric.

- contain all writing mechanics that relates to essay writing;

- cover different requirements and their relevant grades;

- follow clear and understandable statements.

To Learn More, Read Relevant Articles

How to cite a newspaper article in apa 7 with examples, how to write a "who am i" essay: free tips with examples.

Sample Essay Rubric for Elementary Teachers

- Grading Students for Assessment

- Lesson Plans

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.S., Education, Buffalo State College

- B.S., Education, Buffalo State College

An essay rubric is a way teachers assess students' essay writing by using specific criteria to grade assignments. Essay rubrics save teachers time because all of the criteria are listed and organized into one convenient paper. If used effectively, rubrics can help improve students' writing .

How to Use an Essay Rubric

- The best way to use an essay rubric is to give the rubric to the students before they begin their writing assignment. Review each criterion with the students and give them specific examples of what you want so they will know what is expected of them.

- Next, assign students to write the essay, reminding them of the criteria and your expectations for the assignment.

- Once students complete the essay have them first score their own essay using the rubric, and then switch with a partner. (This peer-editing process is a quick and reliable way to see how well the student did on their assignment. It's also good practice to learn criticism and become a more efficient writer.)

- Once peer-editing is complete, have students hand in their essay's. Now it is your turn to evaluate the assignment according to the criteria on the rubric. Make sure to offer students examples if they did not meet the criteria listed.

Informal Essay Rubric

Formal essay rubric.

- Rubrics - Quick Guide for all Content Areas

- How to Create a Rubric in 6 Steps

- Writing Rubrics

- What Is a Rubric?

- Rubric Template Samples for Teachers

- Holistic Grading (Composition)

- Scoring Rubric for Students

- How to Make a Rubric for Differentiation

- Create Rubrics for Student Assessment - Step by Step

- A Simple Guide to Grading Elementary Students

- How to Write a Philosophy of Education for Elementary Teachers

- Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time

- Assignment Biography: Student Criteria and Rubric for Writing

- Creating and Scoring Essay Tests

- 5 Types of Report Card Comments for Elementary Teachers

- How Scaffolding Instruction Can Improve Comprehension

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The Evaluation Essay

Key features of a well-written paper about an evaluative essay about a film, a concise description of the subject.

You should include just enough information to help readers who may not be familiar with your subject understand it. Remember, the goal is to evaluate, not summarize.

For instance, if writing about a movie, you’d want to describe the main plot points, only providing what readers need to understand the context of your evaluation. While you are evaluating the movie, you want to try to avoid retelling the story of it.

Another thing to keep in mind is that depending on your topic and medium, some of this descriptive information may be in visual or audio form.

Clearly Defined Criteria

Since you are evaluating the subject, you will need to determine clear criteria as the basis for your judgment. In reviews or other evaluations written for a broad audience, you can integrate the criteria into the discussion as reasons for your assessment. In more formal evaluations, you may need to announce your criteria explicitly.

For instance, you could evaluate a film based on the stars’ performances, the complexity of their characters, and the film’s coherence. There are lots of other criteria to choose from, depending on your film choice.

A few things to keep in mind when coming up with your criteria:

- Don’t try to have too many things to evaluate. Using three to four elements to evaluate should be enough criteria to support an overall evaluation of the subject.

- Pick things relevant to evaluating your subject. For instance, if you are specifically reviewing a movie, you don’t want to include criteria evaluating the popcorn at the movie theater.

- Remember, you’re going to have to define the criteria for your evaluation, so make sure you pick things you either know about or that you can learn about.

A Knowledgeable Discussion of the Subject

To evaluate something credibly, you need to show that you know it yourself and that you understand its context. Cite many examples showing your knowledge of the film. Some evaluations require that you research what other authoritative sources have said about your subject. You are welcome to refer to other film reviews to show you have researched other views, but your evaluation should be your own.

A Balanced and Fair Assessment

An evaluation is centered on a judgment. You can point out both its weaknesses and strengths. It is important that any judgment be balanced and fair. This is why it’s important to select your criteria before starting your evaluation. Seldom is something all good or all bad, and your audience knows this. If only presenting the positive or negative, your audience may feel you aren’t that credible of a source. While it may feel weird to include less-than-positive comments about something you enjoy, a fair evaluation acknowledges both strengths and weaknesses.

Well-Supported Reasons

You need to argue for your judgment, providing reasons and evidence that might include visual and audio as well as verbal material. Support your reasons with several specific examples from the film. This is also a good place to use knowledge of other movies, movie terminology, and other references to not only support your argument (aka your evaluation) but also show your ethos of the subject.

Step 1: Choosing a Topic

For this assignment, you will choose a film you have watched that was meaningful enough to evaluate. It can be one that was meaningful because it changed your perspective, for instance. You are also welcome to choose a film that was critically acclaimed, but you have objections to it. Choose something that strikes you as a film worth analyzing and discussing.

Things to consider while making this selection:

- What is the purpose of your evaluation? Are you writing to affect your audience’s opinion of a film?

- Who is your audience? To whom are you writing? What will your audience already know about the film? What will they expect to learn from your evaluation of it? Are they likely to agree with you or not?

- What is your stance? What is your attitude toward the subject, and how will you show that you have evaluated it fairly and appropriately? Think about the tone you want to use should it be reasonable? Passionate? Critical?

What film are you going to evaluate in this essay? Make sure it is accessible to you (accessible as in you own it, you have checked it out from the library, or it’s available through a subscription you have like Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney Plus, etc.). You will need to watch it and take detailed notes so that you have specifics, dialogue, etc., to include. So, what film will you evaluate?

Step 2: Generating Ideas and Text

Now that you know the film you want to evaluate, it’s time to watch it. Make sure you take extensive notes as it needs to be clear that you have taken the time to watch and study your film and that you have thought through not only the criteria that you want to talk about but also specific examples of those criteria.

Explore what you already know. Freewrite to answer the following questions:

- What do you know about this subject?

- What are your initial or gut feelings, and why do you feel as you do?

- How does this film reflect or affect your basic values or beliefs?

- How have others evaluated subjects like this?

Now, it’s time to identify criteria. Make a list of criteria you think should be used to evaluate your film. Consider which criteria will likely be important to your audience.

Here are ideas for specific criteria:

- Evaluate your subject. Study your film closely to determine to what extent it meets each of your criteria.

- You may want to list your criteria and take notes related to each one as you watch the film.

- You may develop a rating scale for each criterion to help stay focused on it.

- Come up with a tentative judgment. Choose 3-4 criteria to discuss in your essay.

- Compare your subject with others. Often, evaluating something involves comparing and contrasting it with similar things. We judge movies in comparison with other movies we’ve seen in a similar genre.

- State your judgment as a tentative thesis statement. Your thesis statement should address both pros and cons. “Hawaii Five-O is fun to watch despite its stilted dialogue.” “Of the five sport utility vehicles tested, the Toyota 4 Runner emerged as the best in comfort, power, and durability, though not in styling or cargo capacity.” Both of these examples offer a judgment but qualify it according to the writer’s criteria. Experiment with thesis statements and highlight one you want to use.

- Anticipate other opinions. I think Will Ferrell is a comic genius whose movies are first-rate. You think Will Ferrell is a terrible actor who makes awful movies. How can I write a review of his latest film that you will at least consider? One way is by acknowledging other opinions–and refuting those opinions as best I can. I may not persuade you to see Ferrell’s next film, but I can at least demonstrate that by certain criteria he should be appreciated. You may need to research how others have evaluated your subject.

- Identify and support your reasons. Write out all the reasons you can think of that will convince your audience to accept your judgment. Review your list to identify the most convincing or important reasons. Then, review how well your subject meets your criteria and decide how best to support your reasons through examples, authoritative opinions, statistics, visual or audio evidence, or something else.

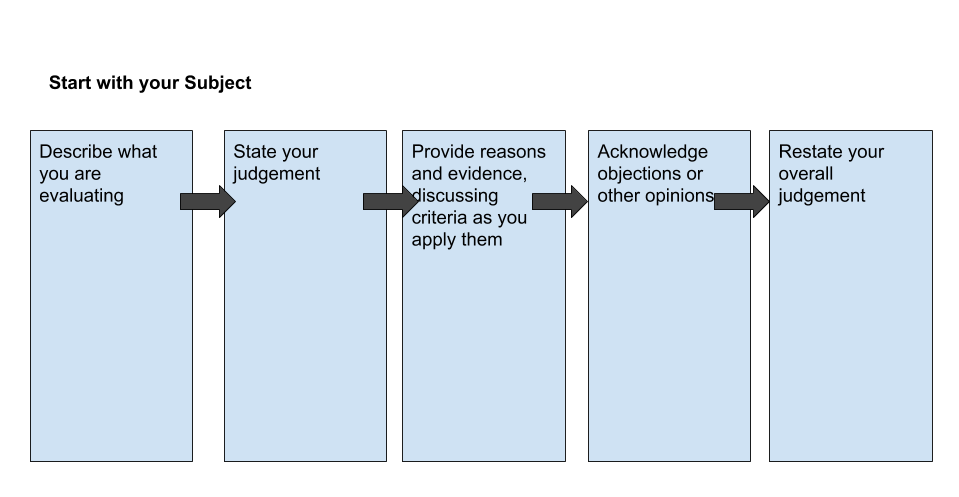

Step 3: Organization of the Evaluation Essay

The following provides two ways to organize your document:

Step 4: Drafting

Now that you’ve watched the thing, written the notes, and collected your thoughts, it’s time to draft. Use the organizational scheme you created in Step 3 to help you create your evaluation.

Step 5: Get Feedback

Step 6: revising.

Once you’ve received feedback, if possible, read through it and then walk away from the work for a little while. This will allow your brain time to process the feedback you received making it much easier to sit back down to make adjustments. While revising, try to avoid messing with punctuation or fixing any grammatical issues. Revision is when you focus on your ideas and make sure they are presented properly, so make sure you’ve set aside plenty of time or scheduled multiple times to go through your project.

Once you’re finished with revision—everything is well defined, claims justified, and conclusions given—it’s time to edit. This is when you correct punctuation and adjust grammatical issues. During this stage, try to only focus on one or two issues at a time. Work all the way through your project looking for these two things, and then start again with the next couple of issues you may need to smooth.

Hopefully, you’ve finished all of these steps before the deadline. If you are running behind, make sure you reach out to your instructor to let them know; they may have some tips to help get you through the final push.

ATTRIBUTIONS AND LICENSE

“ The Evaluation Essay ” by Rachael Reynolds is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License and adapted work from the source below:

Adapted from “ Writing the Evaluation Essay ” by Sara Layton and is used according to CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

UNM Core Writing OER Collection Copyright © 2023 by University of New Mexico is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

What Sentencing Could Look Like if Trump Is Found Guilty

By Norman L. Eisen

Mr. Eisen is the author of “Trying Trump: A Guide to His First Election Interference Criminal Trial.”

For all the attention to and debate over the unfolding trial of Donald Trump in Manhattan, there has been surprisingly little of it paid to a key element: its possible outcome and, specifically, the prospect that a former and potentially future president could be sentenced to prison time.

The case — brought by Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan district attorney, against Mr. Trump — represents the first time in our nation’s history that a former president is a defendant in a criminal trial. As such, it has generated lots of debate about the case’s legal strength and integrity, as well as its potential impact on Mr. Trump’s efforts to win back the White House.

A review of thousands of cases in New York that charged the same felony suggests something striking: If Mr. Trump is found guilty, incarceration is an actual possibility. It’s not certain, of course, but it is plausible.

Jury selection has begun, and it’s not too soon to talk about what the possibility of a sentence, including a prison sentence, would look like for Mr. Trump, for the election and for the country — including what would happen if he is re-elected.