- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Contradictions That Drive Toyota’s Success

- Hirotaka Takeuchi,

- Norihiko Shimizu

Stable and paranoid, systematic and experimental, formal and frank: The success of Toyota, a pathbreaking six-year study reveals, is due as much to its ability to embrace contradictions like these as to its manufacturing prowess.

Reprint: R0806F

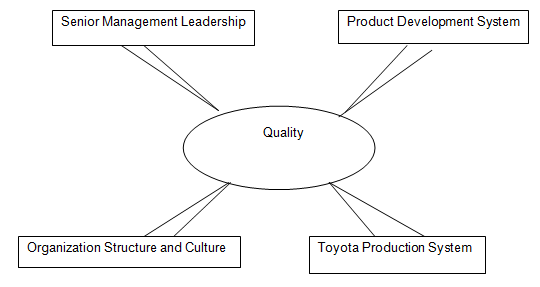

Toyota has become one of the world’s greatest companies only because it developed the Toyota Production System, right? Wrong, say Takeuchi, Osono, and Shimizu of Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo. Another factor, overlooked until now, is just as important to the company’s success: Toyota’s culture of contradictions.

TPS is a “hard” innovation that allows the company to continuously improve the way it manufactures vehicles. Toyota has also mastered a “soft” innovation that relates to human resource practices and corporate culture. The company succeeds, say the authors, because it deliberately fosters contradictory viewpoints within the organization and challenges employees to find solutions by transcending differences rather than resorting to compromises. This culture generates innovative ideas that Toyota implements to pull ahead of competitors, both incrementally and radically.

The authors’ research reveals six forces that cause contradictions inside Toyota. Three forces of expansion lead the company to change and improve: impossible goals, local customization, and experimentation. Not surprisingly, these forces make the organization more diverse, complicate decision making, and threaten Toyota’s control systems. To prevent the winds of change from blowing down the organization, the company also harnesses three forces of integration: the founders’ values, “up-and-in” people management, and open communication. These forces stabilize the company, help employees make sense of the environment in which they operate, and perpetuate Toyota’s values and culture.

Emulating Toyota isn’t about copying any one practice; it’s about creating a culture. And because the company’s culture of contradictions is centered on humans, who are imperfect, there will always be room for improvement.

No executive needs convincing that Toyota Motor Corporation has become one of the world’s greatest companies because of the Toyota Production System (TPS). The unorthodox manufacturing system enables the Japanese giant to make the planet’s best automobiles at the lowest cost and to develop new products quickly. Not only have Toyota’s rivals such as Chrysler, Daimler, Ford, Honda, and General Motors developed TPS-like systems, organizations such as hospitals and postal services also have adopted its underlying rules, tools, and conventions to become more efficient. An industry of lean-manufacturing experts have extolled the virtues of TPS so often and with so much conviction that managers believe its role in Toyota’s success to be one of the few enduring truths in an otherwise murky world.

- Hirotaka Takeuchi is a professor in the strategy unit of Harvard Business School.

- EO Emi Osono ( [email protected] ) is an associate professor;

- NS and Norihiko Shimizu ( [email protected] ) is a visiting professor at Hitotsubashi University’s Graduate School of International Corporate Strategy in Tokyo. This article is adapted from their book Extreme Toyota: Radical Contradictions That Drive Success at the World’s Best Manufacturer , forthcoming from John Wiley & Sons.

Partner Center

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case Analysis, Toyota: "The Lean Mind" 70 Years of innovation

This case study aims to reveal the reasons for Toyota's success and make its experience guide the developing brands to success.

Related Papers

helen turner

Long Range Planning

Peter J. Buckley

Mossimo Sesom

Deborah Nightingale

This Transition-To-Lean Guide is intended to help your enterprise leadership navigate your enterprise’s challenging journey into the promising world of “lean.” You have opened this guide because, in some fashion, you have come to realize that your enterprise must undertake a fundamental transformation in how it sees the world, what it values, and the principles that will become its guiding lights if it is to prosper — or even survive — in this new era of “clock-speed” competition. However you may have been introduced to “lean,” you have undertaken to benefit from its implementation.

Ayesha Majid , Yahya Rehman

Toyota is a name almost everyone is familiar with. It has been the market leader in automobiles specially hybrid and electric automobiles. It has been operational in Pakistan since 1989. Toyota is a one of a kind Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer. As of September 2018, it was the sixth largest company in the world in terms of revenue. The economic conditions however have not been very favorable for the automotive industry. The economy of Pakistan and the consistent increase in dollar rates has taken a huge toll on the sales of the multinational manufacturer. Focus group analysis show that majority of the people preferred Honda over Toyota due to several reasons including near to none change in the designs of Toyota Corolla’s variants. Another factor was that Toyota was seen more as a car for the rural areas which was best suited for a rugged terrain. Although the general perception is that Toyota has better car suspension and fuel efficiency, people would still prefer Honda and other Japanese cars. Respondents said that advertisements played a crucial role but they do not compel the customer to buy a product like a car, there are other factors that are taken under consideration. Pakwheels and olx were the first two online platforms that they mentioned when asked about their go to online source. Family and friends advice played a major role in deciding which car to buy. According to the research conducted by our group through questionnaire, a regression was done and seen that the general perception that a reduction in prices will increase sales was not true because people usually associate low prices with low quality products. According to the regression, only advertisement and product have a significant result. All the variables are positively correlated with each other and less than one and positive indicating a formative relationship to the dependent variable. Branding has an insignificant positive relationship with purchase intention because consumers are only considering three competitors; Honda, Suzuki and Japanese cars.

Volume III of this guide may be used as an in-depth reference source for acquiring deep knowledge about many of the aspects of transitioning to lean. Lean change agents and lean implementation leaders should find this volume especially valuable in preparing their organizations for the lean transformation and in developing and implementing an enterprise level lean implementation plan. The richness and depth of the discussions in this volume should be helpful in charting a course, avoiding pitfalls, and making in-course corrections during implementation. We assume that the reader of Volume III is familiar with the history and general principles of the lean paradigm that are presented in Volume I, Executive Overview. A review of Volume II, Transition to Lean Roadmap may be helpful prior to launching into Volume III. For those readers most heavily involved in the lean transformation, all three volumes should be understood and referenced frequently.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

(Still) learning from Toyota

In the two years since I retired as president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN), I’ve had the good fortune to work with many global manufacturers in different industries on challenges related to lean management. Through that exposure, I’ve been struck by how much the Toyota production system has already changed the face of operations and management, and by the energy that companies continue to expend in trying to apply it to their own operations.

Yet I’ve also found that even though companies are currently benefiting from lean, they have largely just scratched the surface, given the benefits they could achieve. What’s more, the goal line itself is moving—and will go on moving—as companies such as Toyota continue to define the cutting edge. Of course, this will come as no surprise for any student of the Toyota production system and should even serve as a challenge. After all, the goal is continuous improvement.

Room to improve

The two pillars of the Toyota way of doing things are kaizen (the philosophy of continuous improvement) and respect and empowerment for people, particularly line workers. Both are absolutely required in order for lean to work. One huge barrier to both goals is complacency. Through my exposure to different manufacturing environments, I’ve been surprised to find that senior managers often feel they’ve been very successful in their efforts to emulate Toyota’s production system—when in fact their progress has been limited.

The reality is that many senior executives—and by extension many organizations—aren’t nearly as self-reflective or objective about evaluating themselves as they should be. A lot of executives have a propensity to talk about the good things they’re doing rather than focus on applying resources to the things that aren’t what they want them to be.

When I recently visited a large manufacturer, for example, I compared notes with a company executive about an evaluation tool it had adapted from Toyota. The tool measures a host of categories (such as safety, quality, cost, and human development) and averages the scores on a scale of zero to five. The executive was describing how his unit scored a five—a perfect score. “Where?” I asked him, surprised. “On what dimension?”

“Overall,” he answered. “Five was the average.”

When he asked me about my experiences at Toyota over the years and the scores its units received, I answered candidly that the best score I’d ever seen was a 3.2—and that was only for a year, before the unit fell back. What happens in Toyota’s culture is that as soon as you start making a lot of progress toward a goal, the goal is changed and the carrot is moved. It’s a deep part of the culture to create new challenges constantly and not to rest when you meet old ones. Only through honest self-reflection can senior executives learn to focus on the things that need improvement, learn how to close the gaps, and get to where they need to be as leaders.

A self-reflective culture is also likely to contribute to what I call a “no excuse” organization, and this is valuable in times of crisis. When Toyota faced serious problems related to the unintended acceleration of some vehicles, for example, we took this as an opportunity to revisit everything we did to ensure quality in the design of vehicles—from engineering and production to the manufacture of parts and so on. Companies that can use crises to their advantage will always excel against self-satisfied organizations that already feel they’re the best at what they do.

A common characteristic of companies struggling to achieve continuous improvement is that they pick and choose the lean tools they want to use, without necessarily understanding how these tools operate as a system. (Whenever I hear executives say “we did kaizen ,” which in fact is an entire philosophy, I know they don’t get it.) For example, the manufacturer I mentioned earlier had recently put in an andon system, to alert management about problems on the line. 1 1. Many executives will have heard of the andon cord, a Toyota innovation now common in many automotive and assembly environments: line workers are empowered to address quality or other problems by stopping production. Featuring plasma-screen monitors at every workstation, the system had required a considerable development and programming effort to implement. To my mind, it represented a knee-buckling amount of investment compared with systems I’d seen at Toyota, where a new tool might rely on sticky notes and signature cards until its merits were proved.

An executive was explaining to me how successful the implementation had been and how well the company was doing with lean. I had been visiting the plant for a week or so. My back was to the monitor out on the shop floor, and the executive was looking toward it, facing me, when I surprised him by quoting a series of figures from the display. When he asked how I’d done so, I pointed out that the tool was broken; the numbers weren’t updating and hadn’t since Monday. This was no secret to the system’s operators and to the frontline workers. The executive probably hadn’t been visiting with them enough to know what was happening and why. Quite possibly, the new system receiving such praise was itself a monument to waste.

Room to reflect

At the end of the day, stories like this underscore the fact that applying lean is a leadership challenge, not just an operational one. A company’s senior executives often become successful as leaders through years spent learning how to contribute inside a particular culture. Indeed, Toyota views this as a career-long process and encourages it by offering executives a diversity of assignments, significant amounts of training, and even additional college education to help prepare them as lean leaders. It’s no surprise, therefore, that should a company bring in an initiative like Toyota’s production system—or any lean initiative requiring the culture to change fundamentally—its leaders may well struggle and even view the change as a threat. This is particularly true of lean because, in many cases, rank-and-file workers know far more about the system from a “toolbox standpoint” than do executives, whose job is to understand how the whole system comes together. This fact can be intimidating to some executives.

Senior executives who are considering lean management (or are already well into a lean transformation and looking for ways to get more from the effort and make it stick) should start by recognizing that they will need to be comfortable giving up control. This is a lesson I’ve learned firsthand. I remember going to CAPTIN as president and CEO of the company and wanting to get off to a strong start. Hoping to figure out how to get everyone engaged and following my initiatives, I told my colleagues what I wanted. Yet after six or eight months, I wasn’t getting where I wanted to go quickly enough. Around that time, a Japanese colleague told me, “Deryl, if you say ‘do this’ everybody will do it because you’re president, whether you say ‘go this way,’ or ‘go that way.’ But you need to figure out how to manage these issues having absolutely no power at all.”

So with that advice in mind, I stepped back and got a core group of good people together from all over the company—a person from production control, a night-shift supervisor, a manager, a couple of engineers, and a person in finance—and challenged them to develop a system. I presented them with the direction but asked them to make it work.

And they did. By the end of the three-year period we’d set as a target, for example, we’d dramatically improved our participation rate in problem-solving activities—going from being one of the worst companies in Toyota Motor North America to being one of the best. The beauty of the effort was that the team went about constructing the program in ways I never would have thought of. For example, one team member (the production-control manager) wanted more participation in a survey to determine where we should spend additional time training. So he created a storyboard highlighting the steps of problem solving and put it on the shop floor with questionnaires that he’d developed. To get people to fill them out, his team offered the respondents a hamburger or a hot dog that was barbecued right there on the shop floor. This move was hugely successful.

Another tip whose value I’ve observed over the years is to find a mentor in the company, someone to whom you can speak candidly. When you’re the president or CEO, it can be kind of lonely, and you won’t have anyone to talk with. I was lucky because Toyota has a robust mentorship system, which pairs retired company executives with active ones. But executives anywhere can find a sounding board—someone who speaks the same corporate language you do and has a similar background. It’s worth the effort to find one.

Finally, if you’re going to lead lean, you need knowledge and passion. I’ve been around leaders who had plenty of one or the other, but you really need both. It’s one thing to create all the energy you need to start a lean initiative and way of working, but quite another to keep it going—and that’s the real trick.

Room to run

Even though I’m retired from Toyota, I’m still engaged with the company. My experiences have given me a unique vantage point to see what Toyota is doing to push the boundaries of lean further still.

For example, about four years ago Toyota began applying lean concepts from its factories beyond the factory floor—taking them into finance, financial services, the dealer networks, production control, logistics, and purchasing. This may seem ironic, given the push so many companies outside the auto industry have made in recent years to drive lean thinking into some of these areas. But that’s very consistent with the deliberate way Toyota always strives to perfect something before it’s expanded, looking to “add as you go” rather than “do it once and stop.”

Of course, Toyota still applies lean thinking to its manufacturing operations as well. Take major model changes, which happen about every four to eight years. They require a huge effort—changing all the stamping dies, all the welding points and locations, the painting process, the assembly process, and so on. Over the past six years or so, Toyota has nearly cut in half the time it takes to do a complete model change.

Similarly, Toyota is innovating on the old concept of a “single-minute exchange of dies” 2 2. Quite honestly, the single-minute exchange of dies aspiration is really just that—a goal. The fastest I ever saw anyone do it during my time at New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) was about 10 to 15 minutes. and applying that thinking to new areas, such as high-pressure injection molding for bumpers or the manufacture of alloy wheels. For instance, if you were making an aluminum-alloy wheel five years ago and needed to change from one die to another, that would require about four or five hours because of the nature of the smelting process. Now, Toyota has adjusted the process so that the changeover time is down to less than an hour.

Finally, Toyota is doing some interesting things to go on pushing the quality of its vehicles. It now conducts surveys at ports, for example, so that its workers can do detailed audits of vehicles as they are funneled in from Canada, the United States, and Japan. This allows the company to get more consistency from plant to plant on everything from the torque applied to lug nuts to the gloss levels of multiple reds so that color standards for paint are met consistently.

The changes extend to dealer networks as well. When customers take delivery of a car, the salesperson is accompanied by a technician who goes through it with the new owner, in a panel-by-panel and option-by-option inspection. They’re looking for actionable information: is an interior surface smudged? Is there a fender or hood gap that doesn’t look quite right? All of this checklist data, fed back through Toyota’s engineering, design, and development group, can be sent on to the specific plant that produced the vehicle, so the plant can quickly compare it with other vehicles produced at the same time.

All of these moves to continue perfecting lean are consistent with the basic Toyota approach I described: try and perfect anything before you expand it. Yet at the same time, the philosophy of continuous improvement tells us that there’s ultimately no such thing as perfection. There’s always another goal to reach for and more lessons to learn.

Deryl Sturdevant, a senior adviser to McKinsey, was president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN) from 2006 to 2011. Prior to that, he held numerous executive positions at Toyota, as well as at the New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) plant (a joint venture between Toyota and General Motors), in Fremont, California.

Explore a career with us

Over about a four-year period, they showed us how work was actually done in practice in dozens of plants. Kent and I went to Toyota plants and those of suppliers here in the U.S. and in Japan and directly watched literally hundreds of people in a wide variety of roles, functional specialties, and hierarchical levels. I personally was in the field for at least 180 working days during that time and even spent one week at a non-Toyota plant doing assembly work and spent another five months as part of a Toyota team that was trying to teach TPS at a first-tier supplier in Kentucky.

What did you discover?

We concluded that Toyota has come up with a powerful, broadly applicable answer to a fundamental managerial problem. The products we consume and the services we use are typically not the result of a single person's effort. Rather, they come to us through the collective effort of many people each doing a small part of the larger whole. To a certain extent, this is because of the advantages of specialization that Adam Smith identified in pin manufacturing as long ago as 1776 in The Wealth of Nations . However, it goes beyond the economies of scale that accrue to the specialist, such as skill and equipment focus, setup minimization, etc.

The products and services characteristic of our modern economy are far too complex for any one person to understand how they work. It is cognitively overwhelming. Therefore, organizations must have some mechanism for decomposing the whole system into sub-system and component parts, each "cognitively" small or simple enough for individual people to do meaningful work. However, decomposing the complex whole into simpler parts is only part of the challenge. The decomposition must occur in concert with complimentary mechanisms that reintegrate the parts into a meaningful, harmonious whole.

This common yet nevertheless challenging problem is obviously evident when we talk about the design of complex technical devices. Automobiles have tens of thousands of mechanical and electronic parts. Software has millions and millions of lines of code. Each system can require scores if not hundreds of person-work-years to be designed. No one person can be responsible for the design of a whole system. No one is either smart enough or long-lived enough to do the design work single handedly.

Furthermore, we observe that technical systems are tested repeatedly in prototype forms before being released. Why? Because designers know that no matter how good their initial efforts, they will miss the mark on the first try. There will be something about the design of the overall system structure or architecture, the interfaces that connect components, or the individual components themselves that need redesign. In other words, to some extent the first try will be wrong, and the organization designing a complex system needs to design, test, and improve the system in a way that allows iterative congruence to an acceptable outcome.

The same set of conditions that affect groups of people engaged in collaborative product design affect groups of people engaged in the collaborative production and delivery of goods and services. As with complex technical systems, there would be cognitive overload for one person to design, test-in-use, and improve the work systems of factories, hotels, hospitals, or agencies as reflected in (a) the structure of who gets what good, service, or information from whom, (b) the coordinative connections among people so that they can express reliably what they need to do their work and learn what others need from them, and (c) the individual work activities that create intermediate products, services, and information. In essence then, the people who work in an organization that produces something are simultaneously engaged in collaborative production and delivery and are also engaged in a collaborative process of self-reflective design, "prototype testing," and improvement of their own work systems amidst changes in market needs, products, technical processes, and so forth.

It is our conclusion that Toyota has developed a set of principles, Rules-in-Use we've called them, that allow organizations to engage in this (self-reflective) design, testing, and improvement so that (nearly) everyone can contribute at or near his or her potential, and when the parts come together the whole is much, much greater than the sum of the parts.

What are these rules?

We've seen that consistently—across functional roles, products, processes (assembly, equipment maintenance and repair, materials logistics, training, system redesign, administration, etc.), and hierarchical levels (from shop floor to plant manager and above) that in TPS managed organizations the design of nearly all work activities, connections among people, and pathways of connected activities over which products, services, and information take form are specified-in-their-design, tested-with-their-every-use, and improved close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem.

That sounds pretty rigorous.

It is, but consider what the Toyota people are attempting to accomplish. They are saying before you (or you all) do work, make clear what you expect to happen (by specifying the design), each time you do work, see that what you expected has actually occurred (by testing with each use), and when there is a difference between what had actually happened and what was predicted, solve problems while the information is still fresh.

That reminds me of what my high school lab science teacher required.

Exactly! This is a system designed for broad based, frequent, rapid, low-cost learning. The "Rules" imply a belief that we may not get the right solution (to work system design) on the first try, but that if we design everything we do as a bona fide experiment, we can more rapidly converge, iteratively, and at lower cost, on the right answer, and, in the process, learn a heck of lot more about the system we are operating.

You say in your article that the Toyota system involves a rigorous and methodical problem-solving approach that is made part of everyone's work and is done under the guidance of a teacher. How difficult would it be for companies to develop their own program based on the Toyota model?

Your question cuts right to a critical issue. We discussed earlier the basic problem that for complex systems, responsibility for design, testing, and improvement must be distributed broadly. We've observed that Toyota, its best suppliers, and other companies that have learned well from Toyota can confidently distribute a tremendous amount of responsibility to the people who actually do the work, from the most senior, expeirenced member of the organization to the most junior. This is accomplished because of the tremendous emphasis on teaching everyone how to be a skillful problem solver.

How do they do this?

They do this by teaching people to solve problems by solving problems. For instance, in our paper we describe a team at a Toyota supplier, Aisin. The team members, when they were first hired, were inexperienced with at best an average high school education. In the first phase of their employment, the hurdle was merely learning how to do the routine work for which they were responsible. Soon thereafter though, they learned how to immediately identify problems that occurred as they did their work. Then they learned how to do sophisticated root-cause analysis to find the underlying conditions that created the symptoms that they had experienced. Then they regularly practiced developing counter-measures—changes in work, tool, product, or process design—that would remove the underlying root causes.

Sounds impressive.

Yes, but frustrating. They complained that when they started, they were "blissful in their ignorance." But after this sustained development, they could now see problems, root down to their probable cause, design solutions, but the team members couldn't actually implement these solutions. Therefore, as a final round, the team members received training in various technical crafts—one became a licensed electrician, another a machinist, another learned some carpentry skills.

Was this unique?

Absolutely not. We saw the similar approach repeated elsewhere. At Taiheiyo, another supplier, team members made sophisticated improvements in robotic welding equipment that reduced cost, increased quality, and won recognition with an award from the Ministry of Environment. At NHK (Nippon Spring) another team conducted a series of experiments that increased quality, productivity, and efficiency in a seat production line.

What is the role of the manager in this process?

Your question about the role of the manager gets right to the heart of the difficulty of managing this way. For many people, it requires a profound shift in mind-set in terms of how the manager envisions his or her role. For the team at Aisin to become so skilled as problem solvers, they had to be led through their training by a capable team leader and group leader. The team leader and group leader were capable of teaching these skills in a directed, learn-by-doing fashion, because they too were consistently trained in a similar fashion by their immediate senior. We found that in the best TPS-managed plants, there was a pathway of learning and teaching that cascaded from the most senior levels to the most junior. In effect, the needs of people directly touching the work determined the assistance, problem solving, and training activities of those more senior. This is a sharp contrast, in fact a near inversion, in terms of who works for whom when compared with the more traditional, centralized command and control system characterized by a downward diffusion of work orders and an upward reporting of work status.

And if you are hiring a manager to help run this system, what are the attributes of the ideal candidate?

We observed that the best managers in these TPS managed organizations, and the managers in organizations that seem to adopt the Rules-in-Use approach most rapidly are humble but also self-confident enough to be great learners and terrific teachers. Furthermore, they are willing to subscribe to a consistent set of values.

How do you mean?

Again, it is what is implied in the guideline of specifying every design, testing with every use, and improving close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem. If we do this consistently, we are saying through our action that when people come to work, they are entitled to expect that they will succeed in doing something of value for another person. If they don't succeed, they are entitled to know immediately that they have not. And when they have not succeeded, they have the right to expect that they will be involved in creating a solution that makes success more likely on the next try. People who cannot subscribe to these ideas—neither in their words nor in their actions—are not likely to manage effectively in this system.

That sounds somewhat high-minded and esoteric.

I agree with you that it strikes the ear as sounding high principled but perhaps not practical. However, I'm fundamentally an empiricist, so I have to go back to what we have observed. In organizations in which managers really live by these Rules, either in the Toyota system or at sites that have successfully transformed themselves, there is a palpable, positive difference in the attitude of people that is coupled with exceptional performance along critical business measures such as quality, cost, safety, and cycle time.

Have any other research projects evolved from your findings?

We titled the results of our initial research "Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System." Kent and I are reasonably confident that the Rules-in-Use about which we have written are a successful decoding. Now, we are trying to "replicate the DNA" at a variety of sites. We want to know where and when these Rules create great value, and where they do, how they can be implemented most effectively.

Since we are empiricists, we are conducting experiments through our field research. We are part of a fairly ambitious effort at Alcoa to develop and deploy the Alcoa Business System, ABS. This is a fusion of Alcoa's long standing value system, which has helped make Alcoa the safest employer in the country, with the Rules in Use. That effort has been going on for a number of years, first with the enthusiastic support of Alcoa's former CEO, Paul O'Neill, now Secretary of the Treasury (not your typical retirement, eh?) and now with the backing of Alain Belda, the company's current head. There have been some really inspirational early results in places as disparate as Hernando, Mississippi and Poces de Caldas, Brazil and with processes as disparate as smelting, extrusion, die design, and finance.

We also started creating pilot sites in the health care industry. We started our work with a "learning unit" at Deaconess-Glover Hospital in Needham, not far from campus. We've got a series of case studies that captures some of the learnings from that effort. More recently, we've established pilot sites at Presbyterian and South Side Hospitals, both part of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. This work is part of a larger, comprehensive effort being made under the auspices of the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative, with broad community support, with cooperation from the Centers for Disease Control, and with backing from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Also, we've been testing these ideas with our students: Kent in the first year Technology and Operations Management class for which he is course head, me in a second year elective called Running and Growing the Small Company, and both of us in an Executive Education course in which we participate called Building Competitive Advantage Through Operations.

· · · ·

Steven Spear is an Assistant Professor in the Technology and Operations Management Unit at the Harvard Business School.

Other HBS Working Knowledge stories featuring Steven J. Spear: Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System Why Your Organization Isn't Learning All It Should

Developing Skillful Problem Solvers: Introduction

Within TPS-managed organizations, people are trained to improve the work that they perform, they learn to do this with the guidance of a capable supplier of assistance and training, and training occurs by solving production and delivery-related problems as bona fide, hypothesis-testing experiments. Examples of this approach follow.

- A quality improvement team at a Toyota supplier, Taiheiyo, conducted a series of experiments to eliminate the spatter and fumes emitted by robotic welders. The quality circle members, all line workers, conducted a series of complex experiments that resulted in a cleaner, safer work environment, equipment that operated with less cost and higher reliability, and relief for more technically-skilled maintenance and engineering specialists from basic equipment maintenance and repair.

- A work team at NHK (Nippon Spring) Toyota, were taught to conduct a series of experiments over many months to improve the process by which arm rest inserts were "cold molded." The team reduced the cost, shortened the cycle time, and improved the quality while simultaneously developing the capability to take a similar experimental approach to process improvement in the future.

- At Aisin, a team of production line workers progressed from having the skills to do only routine production work to having the skills to identify problems, investigate root causes, develop counter-measures, and reconfigure equipment as skilled electricians and machinists. This transformation occurred primarily through the mechanism of problem solving-based training.

- Another example from Aisin illustrates how improvement efforts—in this case of the entire production system by senior managers—were conducted as a bona fide hypothesis-refuting experiment.

- The Acme and Ohba examples contrast the behavior of managers deeply acculturated in Toyota with that of their less experienced colleagues. The Acme example shows the relative emphasis one TPS acculturated manager placed on problem solving as a training opportunity in comparison to his colleagues who used the problem-solving opportunity as a chance to first make process improvements. An additional example from a Toyota supplier reinforces the notion of using problem solving as a vehicle to teach.

- The data section concludes with an example given by a former employee of two companies, both of which have been recognized for their efforts to be a "lean manufacturer" but neither of which has been trained in Toyota's own methods. The approach evident at Toyota and its suppliers was not evident in this person's narrative.

Defining conditions as problematic

We concluded that within Toyota Production System-managed organizations three sets of conditions are considered problematic and prompt problem-solving efforts. These are summarized here and are discussed more fully in a separate paper titled "Pursuing the IDEAL: Conditions that Prompt Problem Solving in Toyota Production System-Managed Organizations."

Failure to meet a customer need

It was typically recognized as a problem if someone was unable to provide the good, service, or information needed by an immediate or external customer.

Failure to do work as designed

Even if someone was able to meet the need of his or her customers without fail (agreed upon mix, volume, and timing of goods and services), it was typically recognized as a problem if a person was unable to do his or her own individual work or convey requests (i.e., "Please send me this good or service that I need to do my work.") and responses (i.e., "Here is the good or service that you requested, in the quantity you requested.").

Failure to do work in an IDEAL fashion

Even if someone could meet customer needs and do his or her work as designed, it was typically recognized as a problem if that person's work was not IDEAL. IDEAL production and delivery is that which is defect-free, done on demand, in batches of one, immediate, without waste, and in an environment that is physically, emotionally, and professionally safe. The improvement activities detailed in the cases that follow, the reader will see, were motivated not so much by a failure to meet customer needs or do work as designed. Rather, they were motivated by costs that were too high (i.e., Taiheiyo robotic welding operation), batch sizes that were too great (i.e., the TSSC improvement activity evaluated by Mr. Ohba), lead-times that were too long, processes that were defect-causing (i.e., NHK cold-forming process), and by compromises to safety (i.e., Taiheiyo).

Our field research suggests that Toyota and those of its suppliers that are especially adroit at the Toyota Production System make a deliberate effort to develop the problem-solving skills of workers—even those engaged in the most routine production and delivery. We saw evidence of this in the Taiheiyo, NHK, and Aisin quality circle examples.

Forums are created in which problem solving can be learned in a learn-by-doing fashion. This point was evident in the quality circle examples. It was also evident to us in the role played by Aisin's Operations Management Consulting Division (OMCD), Toyota's OMCD unit in Japan, and Toyota's Toyota Supplier Support Center (TSSC) in North America. All of these organizations support the improvement efforts of the companies' factories and those of the companies' suppliers. In doing so, these organizations give operating managers opportunities to hone their problem-solving and teaching skills, relieved temporarily of day to day responsibility for managing, production and delivery of goods and services to external customers.

Learning occurs with the guidance of a capable teacher. This was evident in that each of the quality circles had a specific group leader who acted as coach for the quality circle's team leader. We also saw how Mr. Seto at NHK defined his role as, in part, as developing the problem-solving and teaching skills of the team leader whom he supervised.

Problem solving occurs as bona fide experiments. We saw this evident in the experience of the quality circles who learned to organize their efforts as bona fide experiments rather than as ad hoc attempts to find a feasible, sufficient solution. The documentation prepared by the senior team at Aisin is organized precisely to capture improvement ideas as refutable hypotheses.

Broadly dispersed scientific problem solving as a dynamic capability

Problem solving, as illustrated in this paper, is a classic example of a dynamic capability highlighted in the "resource-based" view of the firm literature.

Scientific problem solving—as a broadly dispersed skill—is time consuming to develop and difficult to imitate. Emulation would require a similar investment in time, and, more importantly, in managerial resources available to teach, coach, assist, and direct. For organizations currently operating with a more traditional command and control approach, allocating such managerial resources would require more than a reallocation of time across a differing set of priorities. It would also require an adjustment of values and the processes through which those processes are expressed. Christensen would argue that existing organizations are particularly handicapped in making such adjustments.

Excerpted with permission from "Developing Skillful Problem Solvers in Toyota Production System-Managed Organizations: Learning to Problem Solve by Solving Problems," HBS Working Paper , 2001.

- About / Contact

- Privacy Policy

- Alphabetical List of Companies

- Business Analysis Topics

Toyota’s Operations Management, 10 Critical Decisions, Productivity

Toyota Motor Corporation’s operations management (OM) covers the 10 decisions for effective and efficient operations. With the global scale of its automobile business and facilities around the world, the company uses a wide set of strategies for the 10 critical decisions of operations management. These strategies account for local and regional automotive market conditions, including the trends examined in the PESTLE analysis (PESTEL analysis) of Toyota . The automaker is an example of successful multinational operations management. These 10 decisions indicate the different areas of the business that require strategic approaches. Toyota also succeeds in emphasizing productivity in all the 10 decisions of operations management.

Toyota’s approaches for the 10 strategic decisions of operations management show the importance of coordinated efforts for ensuring streamlined operations and high productivity in international business. Successful operations management leads to high productivity, which supports competitive advantages over other automakers, such as Ford , General Motors , Tesla , BMW , and Hyundai. Nonetheless, these competitors continuously enhance their operations and create challenges to Toyota’s competitive advantages.

Toyota’s Operations Management, 10 Critical Decision Areas

1. Design of Goods and Services . Toyota addresses this strategic decision area of operations management through technological advancement and quality. The company uses its R&D investments to ensure advanced features in its products. Toyota’s mission statement and vision statement provide a basis for the types and characteristics of these products. Moreover, the automaker accounts for the needs and qualities of dealership personnel in designing after-sales services. Despite its limited influence on dealership employment, Toyota’s policies and guidelines ensure the alignment between dealerships and this area of the company’s operations management.

2. Quality Management . To maximize quality, the company uses its Toyota Production System (TPS). Quality is one of the key factors in TPS. Also, the firm addresses this strategic decision area of operations management through continuous improvement, which is covered in The Toyota Way, a set of management principles. These principles and TPS lead to high-quality processes and outputs, which enable innovation capabilities and other strengths shown in the SWOT analysis of Toyota . In this regard, quality is a critical success factor in the automotive company’s operations.

3. Process and Capacity Design . For this strategic decision area of operations management, Toyota uses lean manufacturing, which is also embodied in TPS. The company emphasizes waste minimization to maximize process efficiency and capacity utilization. Lean manufacturing helps minimize costs and supports business growth, which are objectives of Toyota’s generic strategy for competitive advantage and intensive strategies for growth . Thus, the car manufacturer supports business efficiency and cost-effectiveness in its process and capacity design. Cost-effective processes support the competitive selling prices that the company uses for most of its automobiles.

4. Location Strategy . Toyota uses global, regional, and local location strategies. For example, the company has dealerships and localized manufacturing plants in the United States, China, Thailand, and other countries. The firm also has regional facilities and offices. Toyota’s marketing mix (4Ps) influences the preferred locations for dealerships. The automaker addresses this strategic decision area of operations management through a mixed set of strategies.

5. Layout Design and Strategy . Layout design in Toyota’s manufacturing plants highlights the application of lean manufacturing principles. In this critical decision area, the company’s operations managers aim for maximum efficiency of workflow. On the other hand, dealership layout design satisfies the company’s standards but also includes decisions from dealership personnel.

6. Job Design and Human Resources . The company applies The Toyota Way and TPS for this strategic decision area of operations management. The firm emphasizes respect for all people in The Toyota Way, and this is integrated in HR programs and policies. These programs and policies align with Toyota’s organizational culture (business culture) . Also, the company has training programs based on TPS to ensure lean manufacturing practice. Moreover, Toyota’s company structure (business structure) affects this area of operations management. For example, the types and characteristics of jobs are specific to the organizational division, which can have human resource requirements different from those of other divisions.

7. Supply Chain Management . Toyota applies lean manufacturing for supply chain management. In this strategic decision area of operations management, the company uses automation systems for real-time adjustments in supply chain activity. In this way, the automotive business minimizes the bullwhip effect in its supply chain. It is worth noting that this area of operations management is subject to the bargaining power of suppliers. Even though the Five Forces analysis of Toyota indicates that suppliers have limited power, this power can still affect the automotive company’s productivity and operational effectiveness.

8. Inventory Management . In addressing this strategic decision area of operations management, Toyota minimizes inventory levels through just-in-time inventory management. The aim is to minimize inventory size and its corresponding cost. This inventory management approach is covered in the guidelines of TPS.

9. Scheduling . Toyota follows lean manufacturing principles in its scheduling. The company’s goal for this critical decision area of operations management is to minimize operating costs. Cost-minimization is maintained through HR and resource scheduling that changes according to market conditions.

10. Maintenance . Toyota operates a network of strategically located facilities to support its global business. The company also has a global HR network that supports flexibility and business resilience. In this strategic decision area of operations management, the company uses the global extent of its automotive business reach to ensure optimal and stable productivity. Effective maintenance of assets and business processes optimizes efficiency for Toyota’s sustainability and related CSR and ESG goals .

Productivity at Toyota

Toyota’s operations management uses productivity measures or criteria based on business process, personnel, area of business, and other variables. Some of these productivity measures are as follows:

- Number of product units per time (manufacturing plant productivity)

- Revenues per dealership (dealership productivity)

- Number of batch cycles per time (supply chain productivity)

- Cannas, V. G., Ciano, M. P., Saltalamacchia, M., & Secchi, R. (2023). Artificial intelligence in supply chain and operations management: A multiple case study research. International Journal of Production Research , 1-28.

- Jin, T. (2023). Bridging reliability and operations management for superior system availability: Challenges and opportunities. Frontiers of Engineering Management , 1-15.

- Toyota Motor Corporation – Form 20-F .

- Toyota Motor Corporation – R&D Centers .

- Toyota Production System .

- U.S. Department of Commerce – International Trade Administration – Automotive Industry .

- Copyright by Panmore Institute - All rights reserved.

- This article may not be reproduced, distributed, or mirrored without written permission from Panmore Institute and its author/s.

- Educators, Researchers, and Students: You are permitted to quote or paraphrase parts of this article (not the entire article) for educational or research purposes, as long as the article is properly cited and referenced together with its URL/link.

Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study

Introduction, implementation of tqm in toyota, tqm practices in toyota, benefits of tqm in toyota, examples of tqm in toyota, toyota quality management, toyota tqm implementation challenges.

The Toyota Corporation case study report is based on the implementation of total quality management (TQM) meant to improve the overall performance and operations of this automobile company. TQM involves the application of quality management standards to all elements of the business.

It requires that quality management standards be applied in all branches and at all levels of the organization. The characteristic of Toyota Corporation going through the total quality process is unambiguous and clear.

Toyota has limited interdepartmental barriers, excellent customer and supplier relations, spares time to be spent on training, and the recognition that quality is realized through offering excellent products as well as the quality of the entire firm, including personnel, finance, sales, and other functions.

The top management at Toyota Corporation has the responsibility for quality rather than the employees, and it is their role to provide commitment, support, and leadership to the human and technical processes (Kanji & Asher, 1996).

Whereas the TQM initiative is to succeed, the management has to foster the participation of Toyota Corporation workers in quality improvement and create a quality culture by altering attitudes and perceptions towards quality.

This research report assesses the implementation of TQM and how Toyota manages quality in all organization management systems while focusing on manufacturing quality. The report evaluates the organization management elements required when implementing TQM, identifies, and investigates the challenges facing Quality Managers or Executives in implementing Quality Management Systems.

In order to implement TQM, Toyota corporations focused on the following phases:

- The company extended the management responsibility past the instantaneous services and products

- Toyota examined how consumers applied the products generated, and this enabled the company to develop and improve its commodities

- Toyota focused on the insubstantial impacts on the procedures as well as how such effects could be minimized through optimization

- Toyota focused on the kaizen (incessant process development) in order to ensure that all procedures are measurable, repeatable, and visible.

The commitment from business executives is one of the key TQM implementation principles that make an organization successful. In fact, the organizational commitment present in the senior organizational staff ranges from top to lower administration. These occur through self-driven motives, motivation, and employee empowerment. Total Quality Management becomes achievable at Toyota by setting up the mission and vision statements, objectives, and organizational goals.

In addition, the TQM is achievable via the course of active participation in organizational follow-up actions. These actions denote the entire activities needed and involved during the implementation of the set-out ideologies of the organization. From Toyota Corporation’s report, TQM has been successful through the commitment of executive management and the organizational workforce (Toyota Motor Corporation, 2012).

Through inventory and half the bottlenecks at half cost and time, the adopters of TMS (Toyota Management System) are authorized to manufacture twice above the normal production. To manage the quality in all organizational management systems, the Toyota Production System incorporates different modernisms like strategy or Hoshin Kanri use, overall value supervision, and just-in-time assembly.

The amalgamation of these innovations enables Toyota to have a strong competitive advantage despite the fact that Toyota never originated from all of them. The 1914 Henry Ford invention relied on the just-in-time production model. The Ford system of production, from a grand perspective, warrants massive production, thus quality (Toyota Motor Corporation, 2012).

Kanji and Asher (1996) claim that to manage the minute set of production necessitated by the splintered and small post-war marketplaces, the JIT system focuses on the motion and elimination of waste materials. This reduces crave for work-in-process inventory by wrapping up the long production lines. Toyota Corp wraps the production lines into slashed change-over times, a multi-trained workforce that runs manifold machines, and new-fangled cells into a U shape.

When supplementing the just-in-cells, the system of kanban is employed by the Toyota Corporation to connect the cells that are unable to integrate physically. Equally, the system helps Toyota integrate with other external companies, consumers, and suppliers.

The TQM and the creativity of Toyota proprietors both support the quality at the source. The rectification and discovery of the production problems require the executives to be committed. At the forefront of Toyota operations, the managers integrate a number of forms of operational quality checks to ensure quality management at all levels.

The uninterrupted tests help the Toyota workforce engaging in the assembly course to scrutinize the value of apparatus, implements, and resources utilized in fabrication. The checks help in the scrutiny of the previously performed tasks by other workers. However, the corporation’s own test enables the workers to revise their personal advances in the assembly course.

The Toyota process owners set up the mistake-proofing (Poka-yoke) procedures and devices to capture the awareness of management and involuntarily correct and surface the augmenting problems. This is essential for the critical production circumstances and steps that prove impractical and tricky for Toyota employees to inspect.

Nevertheless, the policy deployment system decentralizes the process of decision-making at Toyota. This context of implementing Total Quality Management originates from Hoshin Kanri’s management by objective (MBO).

This aspect becomes more advantageous to Toyota when dealing with quality management. The system initially puts into practice the coordinated approach and provides a clear structure for the suppliers, producers, and consumers through inter-organizational cost administration. Moreover, Toyota executives can solve the concurrent delivery, cost, and quality bottlenecks, thus replacing and increasing the relatively slow accounting management mechanisms.

Customer focus that leads to the desired customer satisfaction at Toyota Company is one of the major success factors in TQM implementation. For every business to grow, it should have understanding, reliable, and trustworthy customers. The principle of customer satisfaction and focus has been the most presently well-thought-out aspect of Toyota’s manufacturing quality.

The TQM may characteristically involve total business focus towards meeting and exceeding customers’ expectations and requirements by considering their personal interests. The mission of improving and achieving customer satisfaction ought to stream from customer focus.

Thus, when focusing on manufacturing quality, this aspect enhances TQM implementation. The first priorities at Toyota are community satisfaction, employees, owners, consumers, and mission. The diverse consumer-related features from liberty. The concern to care is eminent in Toyota Corporation during manufacturing.

Toyota has three basic perspectives of TQM that are customer-oriented. These are based on its manufacturing process traced back to the 1950s. The strategies towards achieving quality manufacturing, planning, and having a culture towards quality accomplishment are paramount for TQM implementation to remain successful. To enhance and maintain quality through strategic planning schemes, all managers and employers must remain effectively driven.

This involves training workers on principles concerning quality culture and achievement. Scheduling and planning are analytical applications at Toyota Company that purposes in assessing customer demand, material availability, and plant capacity during manufacturing.

The Toyota Corporation has considerable approaches that rank it among the successful and renowned implementers of TQM. From the inherent and designed structure of Toyota, it becomes feasible to comprehend why quality manufacturing is gradually becoming effective. The inspection department is responsible for taking corrective measures, salvaging, and sorting the desired manufactured product or service quality.

The Toyota Corporation also has a quality control system that is involved in determining quality policies, reviewing statistics, and establishing quality manuals or presentation data. Furthermore, quality assurance is one of the integral principles in quality implementation that is practically present at Toyota. The quality assurance and quality inspectors throughout the Toyota Company structure also manage research and development concerning the quality of manufactured products and services.

The Toyota production and operations management system is similarly dubbed as the managerial system. In fact, in this corporation, operational management is also referred to as the production process, production management, or operations (Chary, 2009). These simply incorporate the actual production and delivery of products.

The managerial system involves product design and the associated product process, planning and implementing production, as well as acquiring and organizing resources. With this broad scope, the production and operation managers have a fundamental role to play in the company’s ability to reach the TQM implementation goals and objectives.

The Toyota Corporation operations managers are required to be conversant and familiar with the TQM implementation concepts and issues that surround this functional area. Toyota’s operation management system is focused on fulfilling the requirements of the customers.

The corporation realizes this by offering loyal and express commodities at logical fees and assisting dealers in progressing commodities proffered. As Slack et al. (2009) observed, the basic performance objectives, which pertain to all the Toyota’s operations, include quality, speed, flexibility, dependability, and cost. Toyota Company has been successful in meeting these objectives through its production and operation functions.

Over several decades, Toyota’s operational processes and management systems were streamlined, resulting in the popularly known Toyota Production System. Although the system had been extensively researched, many companies, such as Nissan, experienced difficulties in replicating TPS.

The TPS was conceived when the company realized that producing massive quantities from limited product lines and ensuring large components to achieve maximum economies of scale led to flaws. Its major objectives were to reduce cost, eliminate waste, and respond to the changing needs of the customers. The initial feature of this system was set-up time reduction, and this forms the basis of TQM implementation.

At Toyota Corporation, quality is considered as acting responsibly through the provision of blunder-gratis products that please the target clientele. Toyota vehicles are among the leading brands in customer satisfaction. Due to good quality, its success has kept growing, and in 2012, the company was the best worldwide. Moreover, Toyota has been keen on producing quality vehicles via the utilization of various technologies that improve the performance of the vehicles.

While implementing TQM, Toyota perceives speed as a key element. In this case, speed objective means doing things fast in order to reduce the time spent between ordering and availing the product to the customer.

The TPS method during processing concentrates on reducing intricacy via the use of minute and uncomplicated machinery that is elastic and full-bodied. The company’s human resources and managers are fond of reorganizing streams and designs to promote minimalism. This enhances the speed of production.

Another objective during TQM implementation is dependability. This means timely working to ensure that customers get their products within the promised time. Toyota has included a just-in-time production system comprised of multi-skilled employees who work in teams. The kanban control allows the workers to deliver goods and services as promised. Advancing value and effectiveness appears to be the distress for administrators, mechanical specialists, and other Toyota human resources.

During TQM implementation, Toyota responds to the demands by changing its products and the way of doing business. Chary (2009) argues that while implementing TQM, organizations must learn to like change and develop responsive and flexible organizations to deal with the changing business environment.

Within Toyota plants, this incorporates the ability to adopt the manufacturing resources to develop new models. The company is able to attain an elevated degree of suppleness, manufacturing fairly tiny bunches of products devoid of losses in excellence or output.

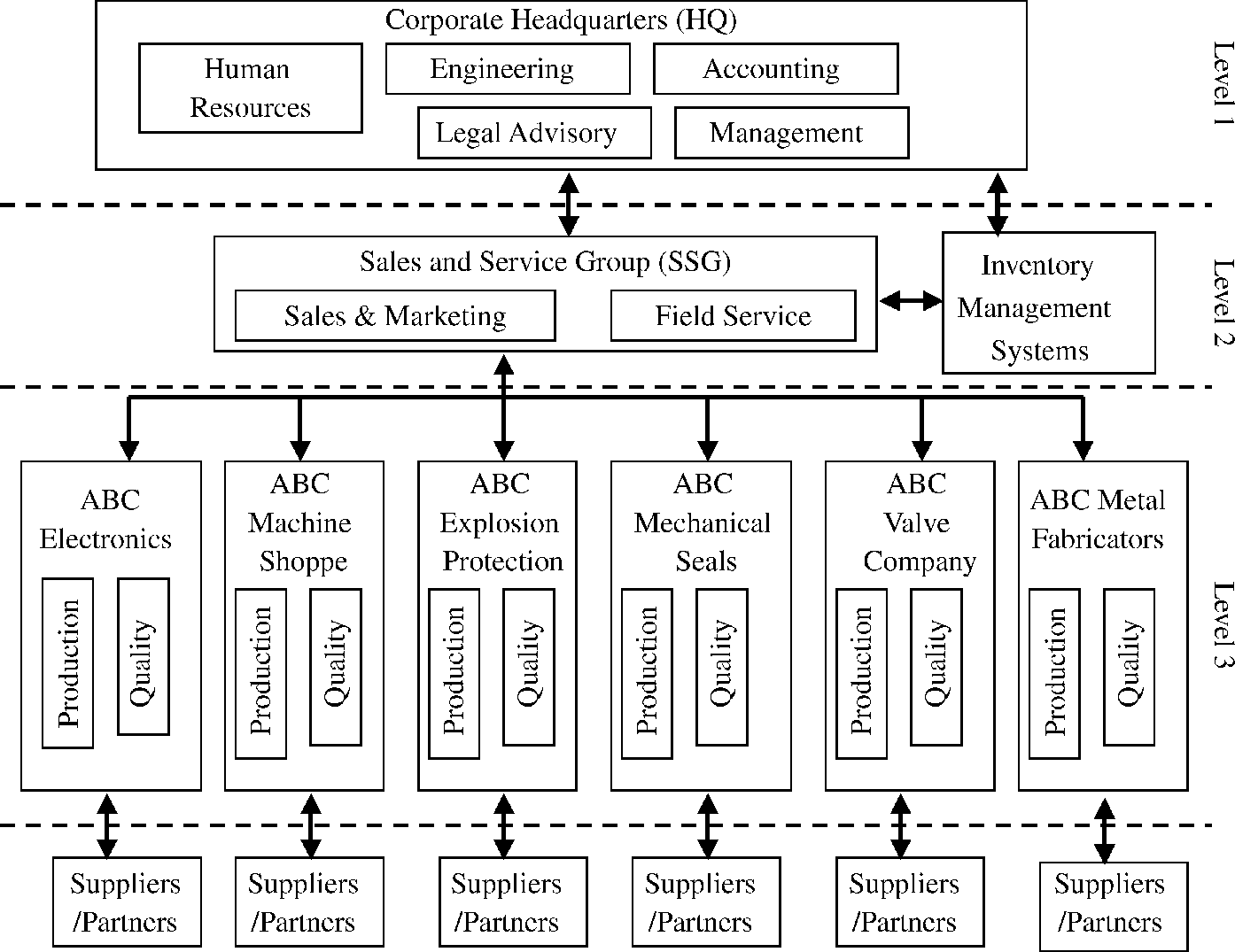

The organizational hierarchy and job descriptions also determine the successful implementation of the TQM. Toyota is amongst the few companies whose organizational structure and task allocation have proved viable in TQM implementation. The company has three levels of management. See the diagram below.

Management hierarchy

Despite the hierarchy and task specification, employees are able to make independent decisions and take corrective measures when necessary to ensure quality during production. Team working is highly encouraged at Toyota Corporation, and this plays a significant role during TQM implementation. All stakeholders are incorporated in quality control initiatives to ensure client demands are satisfied.

However, all employees are required to carry out their assigned tasks, and the management closely supervises the ways of interactions between workers. The management ensures that the manufacturing lines are well-built and all employees are motivated to learn how to improve the production processes.

Toyota is among the few manufacturers in the complete automobile industry that consistently profited during the oil crisis in 1974. The discovery was the unique team working of the Japanese that utilized scientific management rules (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2007).

The joint effort in Japan, usually dubbed Toyotaism, is a kind of job association emphasizing ‘lean-assembly.’ The technique merges just-in-time production, dilemma-answering groups, job equivalence, authoritative foremost-streak administration, and continued procedure perfection.

Just-in-time (JIT) assembly scheme attempts to accomplish all clients’ needs instantly, devoid of misuse but with ideal excellence. JIT appears to be dissimilar from the conventional functional performances in that it emphasizes speedy production and ravage purging that adds to stumpy supply.

Control and planning of many JIT approaches are concerned directly with pull scheduling, leveled scheduling, kanban control, synchronization of flow, and mixed-model scheduling (Slack et al., 2009).

Toyota appears to be amongst the principal participants in changing Japan to a kingpin in car production. Companies, which have adopted the company’s production system, have increased efficiency and productivity. The 2009 industrial survey of manufacturers indicates that many world-class firms have adopted continuous-flow or just-in-time production and many techniques Toyota has been developing many years ago.

In addition, the manufacturing examination of top plant victors illustrates that the mainstream them utilize lean production techniques widely. Thus, team-working TPS assists Toyota Corporation in the implementation of TQM.

Executives and Quality Managers face some challenges while implementing Quality Management Systems in organizations. In fact, with a lack of the implementation resources such as monetary and human resources in any organization, the implementation of TQM cannot be successful. Towards the implementation of programs and projects in organizations, financial and human resources have become the pillar stones.

The approach of TQM impels marketplace competence from all kinds of organizational proceeds to ensure profitability and productivity. To meet the desired results in TQM implementation, an organization ought to consider the availability of human and financial resources that are very important for the provision of an appropriate milieu for accomplishing organizational objectives.

In the case of Toyota, which originated and perfected the philosophy of TQM, the Executives, and Quality Managers met some intertwined problems during TQM implementation. The flaw in the new product development is increasingly becoming complicated for the managers to break and accelerate, thus creating reliability problems. Besides, secretive culture and dysfunctional organizational structure cause barriers in communication between the top management, thus, in turn, augmenting public outrage.

The top executives may fail to provide and scale up adequate training to the suppliers and new workforces. As a result, cracks are created in the rigorous TPS system. In addition, a lack of leadership at the top management might cause challenges in the implementation of TQM. Therefore, in designing the organizational structures and systems that impact quality, the senior executives and managers must be responsible, as elaborated in Figure 2 below.

Total Quality Management is a concept applied in the automobile industry, including the Toyota Corporation. It focuses on continuous improvement across all branches and levels of an organization. Being part of Toyota, the concept defines the way in which the organization can create value for its customers and other stakeholders. Through TQM, Toyota Corporation has been able to create value, which eventually leads to operation efficiencies.

These efficiencies have particularly been achieved by continuous correction of deficiencies identified in the process. A particular interest is the central role that information flow and management have played in enabling TQM initiatives to be implemented, especially through continuous learning and team working culture.

The Toyota way (kaizen), which aims at integrating the workforce suggestions while eliminating overproduction and manufacturing wastes, helps the company to respect all the stakeholders and give clients first priority. The objectives are realized through TPS.

Chary, D. 2009, Production and operations management , Tata McGraw-Hill Education Press, Mumbai.

Huczynski, A. & Buchanan, D. 2007, Organizational behavior; an introductory text, Prentice Hall, New York, NY.

Kanji, G. K. & Asher, M. 1996, 100 methods for total quality management , SAGE Thousands Oak, CA.

Slack, N. et al. 2009, Operations and process management: principles and practice for strategic management, Prentice Hall, New York, NY.

Toyota Motor Corporation 2012, Annual report 2012. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 30). Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study. https://ivypanda.com/essays/total-quality-management-tqm-implementation-toyota/

"Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study." IvyPanda , 30 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/total-quality-management-tqm-implementation-toyota/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study'. 30 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study." March 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/total-quality-management-tqm-implementation-toyota/.

1. IvyPanda . "Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study." March 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/total-quality-management-tqm-implementation-toyota/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Implementation of Total Quality Management (TQM): Toyota Case Study." March 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/total-quality-management-tqm-implementation-toyota/.

- Synchronous and Just-In-Time Manufacturing and Planning

- Just-in-Time Learning Approach

- The Just-In-Time Concept in Operations Management

- Provision of Just-In-Time Technology

- Major Global Corporation: Toyota

- Total “Just-In-Time” Management, Its Pros and Cons

- Just-In-Time Training Principles in the Workplace

- First World Hotel: Just-in-Time Manufacturing Model

- Motorola Company's Just-in-Time Implementation

- Toyota Motor Corporation's Sustainability

- Barriers and Facilitators of Workplace Learning

- The Science of Behavior in Business

- Standards, models, and quality: Management

- Managerial and Professional Development: Crowe Horwath CPA limited

- Managerial and Professional Development: Deloitte & Touché Company

Case Study: Toyota's Response to the 2011 Earthquake and Tsunami

Toyota, a name synonymous with unparalleled excellence and innovation in the automobile industry, faced one of its most challenging adversities following the catastrophic earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in March 2011. This natural disaster not only caused significant loss of life and property, but it also brought many industries, including automotive, to a standstill. However, Toyota’s response to this crisis serves as a lesson in resilience, adaptability, and strategic foresight.

1. Immediate Impact of the Disaster

The Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent tsunami devastated the Tōhoku region, leading to disruptions in the supply chain. Toyota, like many Japanese automakers, heavily depended on suppliers from this region. As a result, many factories had to halt their operations due to the shortage of essential components.

Losses: Toyota reported that the disaster affected the production of over 150,000 vehicles. Apart from local consequences, this disruption resonated throughout the global market since Toyota is a major player in international car exports.

2. Crisis Management and Initial Response

In the face of adversity, Toyota's management showcased exceptional leadership. They prioritized the safety of their employees and immediately implemented disaster recovery plans.

Employee Safety: Toyota ensured that all its workers were safe, and the ones affected directly by the disaster received the necessary support.

Communication: Transparency with stakeholders was maintained. Toyota updated the public, investors, and its employees regularly about the factory shutdowns and the expected time frame of production resumption.

Supply Chain Evaluation: Given the intricate and interconnected nature of Toyota's supply chain, the company diligently assessed the extent of disruption, evaluating how many of their suppliers were affected.

3. Strategic Shift in Supply Chain Management

Toyota realized that to mitigate such vulnerabilities in the future, a revamp of their supply chain strategy was essential.

Multi-Sourcing: To avoid over-reliance on a single supplier, Toyota started the practice of multi-sourcing, ensuring that even if one supplier faced difficulties, an alternative source was available.

Increased Inventory: Though the "Just-In-Time" system is efficient, in the face of disasters, it can be a liability. Thus, Toyota started keeping slightly higher inventories of critical components.

Supplier Collaboration: Toyota worked closely with its suppliers, helping them in their recovery efforts and ensuring that even the smaller suppliers had robust contingency plans in place.

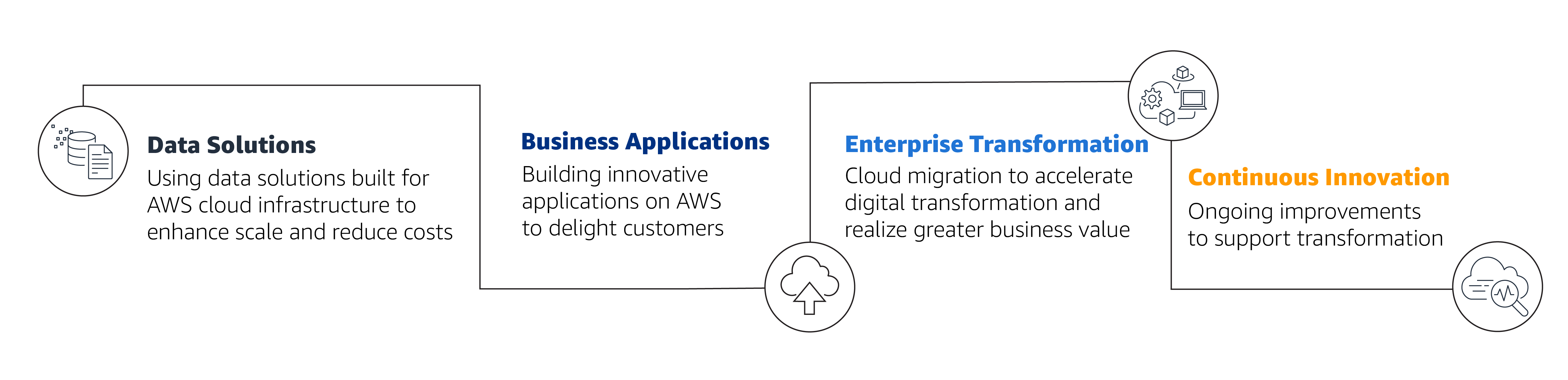

4. Emphasis on Technological Integration

Post-disaster, Toyota intensified its focus on technology to enhance resilience.

Digital Twin Technology: Toyota employed this to create virtual representations of its supply chain. This tech allowed them to simulate various scenarios and develop effective responses to potential disruptions.

AI & Data Analytics: By analyzing vast amounts of data, Toyota could predict potential supply chain vulnerabilities and take preemptive measures.

5. Long-Term Outcomes of the Strategic Shift

Toyota's strategic decisions post the 2011 disaster bore fruitful results.

Resilient Supply Chain: With the revamped supply chain system, Toyota was better equipped to handle subsequent challenges, including global economic shifts or other natural disasters.

Enhanced Stakeholder Confidence: The company's proactive and transparent approach post-disaster bolstered confidence among investors, customers, and employees.

Industry Benchmark: Toyota's response served as a case study for many corporations worldwide, highlighting the importance of adaptability and foresight in crisis management.

The 2011 earthquake and tsunami were unprecedented in their devastation, but they also served as a profound learning experience for global giants like Toyota. By prioritizing the safety of its people, maintaining open communication, and strategically overhauling its supply chain, Toyota transformed a crisis into an opportunity for long-term growth and stability.

In an ever-changing global landscape, Toyota's response to the 2011 disaster underscores the importance of resilience, adaptability, and continuous learning. It serves as a testament to the fact that even in the face of adversity, with the right approach, businesses can not only recover but thrive.

Related Posts

- Case Example: Building Aluminum Gutters on a Level Production Schedule - These days aluminum gutters for houses, at least in the U.S., are mostly built to order, on-site at the house. Rolls of materials are brought to the job site, where...

- Toyota’s Mentor/Mentee Case Example - Table of Contents Setup Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 6 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 The best way to explain Toyota’s mentor/mentee teaching approach is to show it in action. The...

- The Essence of Toyota Management System - Table of Contents The History and Evolution of TMS The Core Principles of TMS Practices & Techniques Modern Adaptations of TMS The Future of TMS In the world of management,...

- The Principle: Find Solid Partners and Grow Together to Mutual Benefit in the Long Term - Go to a conference on supply chain management and what are you likely to hear? You will learn a lot about “streamlining” the supply chain through advanced information technology. If...

- Toyota's Vision and Mission: A Deep Dive - In a world of ever-evolving industries and shifting corporate landscapes, Toyota Motor Corporation stands tall as a beacon of longevity, innovation, and excellence. Its commitment to customer satisfaction, environmental sustainability,...

- Toyota’s Mission Statement and Guiding Principles - We get a flavor of what distinguishes Toyota from excerpts of its mission statement for its North American operations compared with that of Ford . Ford’s mission statement seems reasonable....

- Summary Discussion of the Toyota Mentor/Mentee Case - Table of Contents 1. How Did You Feel as You Read Through the Case? 2. How Long Do You Think the Story in the Case Took? 3. What Would Have...

- The 14 Principles of the Toyota Way - The Toyota Way, a management philosophy that has propelled Toyota to its current position as a global leader in efficiency and quality, is underpinned by 14 key principles. These principles...