Advertisement

Drivers and challenges of precision agriculture: a social media perspective

- Published: 04 October 2020

- Volume 22 , pages 1019–1044, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Martinson Ofori ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6581-8909 1 &

- Omar El-Gayar 1

3414 Accesses

32 Citations

14 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Precision agriculture, which has existed for over four decades, ensures efficient use of agricultural resources for increased productivity and sustainability with the use of technology. Due to the lingering perception that the adoption of precision agriculture has been slow, this study examines public thoughts on the practice of precision agriculture by employing social media analytics. A machine learning-based social media analytics tool—trained to identify and classify posts using lexicons, emoticons, and emojis—was used to capture sentiments and emotions of social media users towards precision agriculture. The study also validated the drivers and challenges of precision agriculture by comparing extant literature with social media data. By mining online data from January 2010 to December 2019, this research captured over 40,000 posts discussing a myriad of concerns related to the practice. An analysis of these posts uncovered joy as the most predominant emotion, also reflected the prevalence of positive sentiments. Robust regulatory and institutional policies that promote both national and international agenda for PA adoption, and the potential of agricultural technology adoption to result in net-positive job creation were identified as the most prevalent drivers. On the other hand, the cost and complexity of currently available technologies, as well as the need for proper data security and privacy were the most common challenges present in social media dialogue.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Media and Innovation

Making Sense of Governmental Activities Over Social Media: A Data-Driven Approach

Realizing Social-Media-Based Analytics for Smart Agriculture

https://www.ispag.org/ .

Asur, S., & Huberman, B. A. (2010). Predicting the future with social media. In 2010 IEEE/WIC/ACM international conference on web intelligence and intelligent agent technology (pp. 492–499). https://doi.org/10.1109/WI-IAT.2010.63 .

Aubert, B. A., Schroeder, A., & Grimaudo, J. (2012). IT as enabler of sustainable farming: An empirical analysis of farmers’ adoption decision of precision agriculture technology. Decision Support Systems, 54 (1), 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.07.002 .

Article Google Scholar

Bakshi, R. K., Kaur, N., Kaur, R., & Kaur, G. (2016). Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. In 2016 3rd international conference on computing for sustainable global development (INDIACom) (pp. 452–455).

Balafoutis, A. T., Beck, B., Fountas, S., Tsiropoulos, Z., Vangeyte, J., van der Wal, T., et al. (2017). Smart farming technologies—Description, taxonomy and economic impact. In S. M. Pedersen & K. M. Lind (Eds.), Precision agriculture: technology and economic perspectives (pp. 21–77). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68715-5_2 .

Bian, J., Yoshigoe, K., Hicks, A., Yuan, J., He, Z., Xie, M., et al. (2016). Mining Twitter to assess the public perception of the “Internet of Things”. PLoS ONE, 11 (7), e0158450. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158450 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bort, J. (2014, March 14). Bill Gates: People don’t realise how many jobs will soon be replaced by software bots . Business Insider Australia. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/bill-gates-bots-are-taking-away-jobs-2014-3. .

CEMA - European Agricultural Machinery. (2017, February 13). Digital farming: What does it really mean? https://www.cema-agri.org/page/digital-farming-what-does-it-really-mean. .

Choi, S. L. (2016). Integrating social media and rainfall data to understand the impacts of severe weather in Argentina. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://hdl.handle.net/2142/90667.

Clercq, M. D., Vats, A., & Biel, A. (2018). Agriculture 4.0: The future of farming technology. World Government Summit , 30.

Connolly, A. J., & Phillips-Connolly, K. (2012). Can agribusiness feed billion new people…and save the planet? A GLIMPSE into the future. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15 , 14.

Google Scholar

Connolly, A. J., Sodre, L. R., & Phillips-Connolly, K. (2016a). GLIMPSE 2.0: A framework to feed the world. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 19 (4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2015.0202 .

Connolly, A. J., Sodre, L. R., & Potocki, A. D. (2016b). GLIMPSE: Using social media to identify the barriers facing farmers’ quest to feed the world. Social Networking, 05 (04), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.4236/sn.2016.54012 .

Crimson Hexagon. (2018a). Enterprise consumer insights | Forsight from Crimson Hexagon . https://www.crimsonhexagon.com/forsight/. .

Crimson Hexagon. (2018b, December 10). Emotion analysis: Overview . Crimson Hexagon. https://help.crimsonhexagon.com/hc/en-us/articles/211129163-Emotion-Analysis-Overview. .

Crimson Hexagon. (2019a, March 6). Explore tab: Topic wheel section . Crimson Hexagon. https://help.crimsonhexagon.com/hc/en-us/articles/203641365-Explore-Tab-Topic-Wheel-Section. .

Crimson Hexagon. (2019b, August 18). Explore tab: Clusters . Crimson Hexagon. https://help.crimsonhexagon.com/hc/en-us/articles/202913009-Explore-Tab-Clusters. .

Crimson Hexagon. (2019c, December 10). Sentiment analysis: Overview . Crimson Hexagon. https://help.crimsonhexagon.com/hc/en-us/articles/203523885-Sentiment-Analysis-Overview. .

Di Consiglio, L., Reis, F., Lehtonen, R., Beręsewicz, M., Karlberg, M., European Commission, & Statistical Office of the European Union. (2018). An overview of methods for treating selectivity in big data sources: 2018 edition. .

Efron, M. (2010). Hashtag retrieval in a microblogging environment. In Proceeding of the 33rd international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval , 787788.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6 (3/4), 169–200.

El-Gayar, O., Nasralah, T., & Elnoshokaty, A. (2019). Wearable devices for health and wellbeing: Design insights from Twitter. In 52nd Hawaii international conference on systems sciences (HICSS-52’19) .

El-Gayar, O., & Ofori, M. (2020). Disrupting agriculture: The status and prospects for ai and big data in smart agriculture. In M. Strydom & S. Buckley (Eds.), AI and big data’s potential for disruptive innovation . IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9687-5.ch007 .

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (FAO). (2020). Climate-smart agriculture . https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture/en/. .

George, D. R. (2011). “Friending Facebook?” A minicourse on the use of social media by health professionals. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 31 (3), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.20129 .

Hanna, R., Rohm, A., & Crittenden, V. L. (2011). We’re all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Business Horizons, 54 (3), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.007 .

Harvey, C. A., Chacón, M., Donatti, C. I., Garen, E., Hannah, L., Andrade, A., et al. (2014). Climate-smart landscapes: Opportunities and challenges for integrating adaptation and mitigation in tropical agriculture: Climate-smart landscapes. Conservation Letters, 7 (2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12066 .

Hazell, P., & Wood, S. (2008). Drivers of change in global agriculture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363 (1491), 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2166 .

Hopkins, D. J., & King, G. (2010). A method of automated nonparametric content analysis for social science. American Journal of Political Science, 54 (1), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00428.x .

IFAD. (2016). Fostering inclusive rural transformation. In Rural Development Report 2016 . International Fund for Agricultural Development. https://www.ifad.org/documents/30600024/e8e9e986-2fd9-4ec4-8fe3-77e99af934c4. .

Jackson, L. A., Ervin, K. S., Gardner, P. D., & Schmitt, N. (2001). The racial digital divide: Motivational, affective, and cognitive correlates of internet use. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31 (10), 2019–2046. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00162.x .

Kamilaris, A., Kartakoullis, A., & Prenafeta-Boldú, F. X. (2017). A review on the practice of big data analysis in agriculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 143 , 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2017.09.037 .

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53 (1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003 .

Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (1999). The psychological origins of perceived usefulness and ease-of-use. Information & Management, 35 (4), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(98)00096-2 .

Kernecker, M., Knierim, A., Wurbs, A., Kraus, T., & Borges, F. (2020). Experience versus expectation: Farmers’ perceptions of smart farming technologies for cropping systems across Europe. Precision Agriculture, 21 , 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-019-09651-z .

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology . California: SAGE.

Krotov, V., & Silva, L. (2018). Legality and ethics of web scraping. In AMCIS 2018 proceedings . https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2018/DataScience/Presentations/17.

Kshetri, N. (2014). The emerging role of Big Data in key development issues: Opportunities, challenges, and concerns. Big Data & Society, 1 (2), 205395171456422. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951714564227 .

Kwak, H., Lee, C., Park, H., & Moon, S. (2010). What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on world wide web - WWW ’10 , 591. https://doi.org/10.1145/1772690.1772751 .

Latta, R. E. (2018, July 24). Text - H.R.4881 - 115th Congress (2017–2018): Precision Agriculture Connectivity Act of 2018 [Webpage]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4881/text. .

Lee, G., & Kwak, Y. H. (2012). An open government maturity model for social media-based public engagement. Government Information Quarterly, 29 (4), 492–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.06.001 .

Lesser, A. (2014, October 8). Big data and big agriculture . https://gigaom.com/report/big-data-and-big-agriculture/. .

Lipizzi, C., Iandoli, L., & Ramirez Marquez, J. E. (2015). Extracting and evaluating conversational patterns in social media: A socio-semantic analysis of customers’ reactions to the launch of new products using Twitter streams. International Journal of Information Management, 35 (4), 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.04.001 .

Lleida University. (2020). Precision agriculture definitions . https://www.grap.udl.cat/en/presentation/pa_definitions.html. .

Lowenberg-DeBoer, J., & Erickson, B. (2019). Setting the record straight on precision agriculture adoption. Agronomy Journal, 111 (4), 1552. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2018.12.0779 .

Lowenberg-DeBoer, J., Huang, I. Y., Grigoriadis, V., & Blackmore, S. (2019). Economics of robots and automation in field crop production. Precision Agriculture . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-019-09667-5 .

Lynch, C. (2015, October 15). Stephen Hawking on the future of capitalism and inequality . CounterPunch.Org. https://www.counterpunch.org/2015/10/15/stephen-hawkings-on-the-tuture-of-capitalism-and-inequality/. .

McCarthy, N., Lipper, L., & Zilberman, D. (2017). Economics of climate smart agriculture: An overview. In Climate smart agriculture: Building resilience to climate change (1st Ed.). Springer.

Misaki, E., Apiola, M., Gaiani, S., & Tedre, M. (2018). Challenges facing sub-Saharan small-scale farmers in accessing farming information through mobile phones: A systematic literature review. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 84 (4), e12034. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12034 .

Moreno, M. A., Goniu, N., Moreno, P. S., & Diekema, D. (2013). Ethics of social media research: Common concerns and practical considerations. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16 (9), 708–713. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0334 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Novak, P. K., Smailović, J., Sluban, B., & Mozetič, I. (2015). Sentiment of emojis. PLoS ONE . https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144296 .

Ofori, M., & El-Gayar, O. (2019). The state and future of smart agriculture: Insights from mining social media. IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), 2019 , 5152–5161. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData47090.2019.9006587 .

Özdemir, V., & Hekim, N. (2018). Birth of industry 5.0: making sense of big data with artificial intelligence, “The Internet of Things” and next-generation technology policy. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology, 22 (1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2017.0194 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pathak, H. S., Brown, P., & Best, T. (2019). A systematic literature review of the factors affecting the precision agriculture adoption process. Precision Agriculture, 20 (6), 1292–1316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-019-09653-x .

Pierpaoli, E., Carli, G., Pignatti, E., & Canavari, M. (2013). Drivers of precision agriculture technologies adoption: A literature review. Procedia Technology, 8 , 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.11.010 .

Porter, J. R., Xie, L., Challinor, A. J., Cochrane, K., Howden, S. M., Iqbal, M. M., et al. (2014). Food security and food production systems. In K. Hakala & P. Aggarwal (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 659–708). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Preissing, J., Leeuwis, C., Hall, A., van Weperen, W., & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Eds.). (2013). Facing the challenges of climate change and food security: The role of research, extension and communication for development . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Read, W., Robertson, N., & McQuilken, L. (2011). A novel romance: The technology acceptance model with emotional attachment. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 19 (4), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.07.004 .

Robert, P. C. (2002). Precision agriculture: A challenge for crop nutrition management. In W. J. Horst, A. Bürkert, N. Claassen, H. Flessa, W. B. Frommer, H. Goldbach, W. Merbach, H.-W. Olfs, V. Römheld, B. Sattelmacher, U. Schmidhalter, M. K. Schenk, & N. v. Wirén (Eds.), Progress in plant nutrition: Plenary lectures of the XIV international plant nutrition colloquium: Food security and sustainability of agro-ecosystems through basic and applied research (pp. 143–149). Springer, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2789-1_11 .

Robson, C. (2002). Real world research: A resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers (2nd ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Roser, M. (2020). Employment in agriculture. Our World in Data . https://ourworldindata.org/employment-in-agriculture. .

Runge, K. K., Yeo, S. K., Cacciatore, M., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D., Xenos, M., et al. (2013). Tweeting nano: How public discourses about nanotechnology develop in social media environments. Journal of Nanoparticle Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-012-1381-8 .

Saidu, A., Clarkson, A. M., Adamu, S. H., Mohammed, M., & Jibo, I. (2017). Application of ICT in agriculture: Opportunities and challenges in developing countries. International Journal of Computer Science and Mathematical Theory, 3 (1), 11.

Saravanan, M., & Perepu, S. K. (2019). Realizing social-media-based analytics for smart agriculture. The Review of Socionetwork Strategies, 13 (1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12626-019-00035-3 .

Say, S. M., Keskin, M., Sehri, M., & Sekerli, Y. E. (2017). Adoption of precision agriculture technologies in developed and developing countries . 14.

Statista. (2018). Number of social media users worldwide 2010–2021 . Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/. .

Steenwerth, K. L., Hodson, A. K., Bloom, A. J., Carter, M. R., Cattaneo, A., Chartres, C. J., et al. (2014). Climate-smart agriculture global research agenda: Scientific basis for action. Agriculture & Food Security, 3 (1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/2048-7010-3-11 .

Stevens, T., Aarts, N., Termeer, C., & Dewulf, A. (2016). Social media as a new playing field for the governance of agro-food sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18 , 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.11.010 .

Sykuta, M. E. (2016). Big data in agriculture: Property rights, privacy and competition in ag data services. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review Special Issue, 19 (A), 18.

Tey, Y. S., & Brindal, M. (2012). Factors influencing the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: A review for policy implications. Precision Agriculture, 13 (6), 713–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-012-9273-6 .

Walter, A., Finger, R., Huber, R., & Buchmann, N. (2017). Opinion: Smart farming is key to developing sustainable agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114 (24), 6148–6150. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707462114 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wang, Y., Jin, L., & Mao, H. (2019). Farmer cooperatives’ intention to adopt agricultural information technology—Mediating effects of attitude. Information Systems Frontiers, 21 (3), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-019-09909-x .

Weltzien, C. (2016). Digital agriculture—or why agriculture 4.0 still offers only modest returns. Landtechnik, 71 (2), 66–68.

Williams, H. T. P., McMurray, J. R., Kurz, T., & Hugo Lambert, F. (2015). Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 32 , 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006 .

Wiseman, L., Sanderson, J., Zhang, A., & Jakku, E. (2019). Farmers and their data: An examination of farmers’ reluctance to share their data through the lens of the laws impacting smart farming. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 90–91 , 100301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2019.04.007 .

Wojcik, S., & Hughes, A. (2019, April 24). How Twitter users compare to the general public. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech . https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/04/24/sizing-up-twitter-users/. .

Wolfert, S., Ge, L., Verdouw, C., & Bogaardt, M.-J. (2017). Big data in smart farming—A review. Agricultural Systems, 153 , 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.023 .

Wolfert, S., Goense, D., & Sorensen, C. A. G. (2014). A future internet collaboration platform for safe and healthy food from farm to fork. In 2014 annual SRII global conference (pp. 266–273). https://doi.org/10.1109/SRII.2014.47 .

World Bank. (2019, December 4). Climate smart agriculture investment plans: Bringing CSA to life [Text/HTML]. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/publication/climate-smart-agriculture-investment-plans-bringing-climate-smart-agriculture-to-life. .

World Bank. (2020). Climate-smart agriculture [Text/HTML]. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climate-smart-agriculture .

Wuebbles, D. J., Fahey, D. W., Hibbard, K. A., DeAngelo, B., Doherty, S., Hayhoe, K., et al. (2017). Executive summary. In D. J. Wuebbles, D. W. Fahey, K. A. Hibbard, D. J. Dokken, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Climate science special report: Fourth national climate assessment (Vol. I, pp. 12–34). U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/J0DJ5CTG .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Business and Information Systems, Dakota State University, Madison, USA

Martinson Ofori & Omar El-Gayar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Martinson Ofori .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ofori, M., El-Gayar, O. Drivers and challenges of precision agriculture: a social media perspective. Precision Agric 22 , 1019–1044 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-020-09760-0

Download citation

Accepted : 26 September 2020

Published : 04 October 2020

Issue Date : June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-020-09760-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media

- Precision agriculture

- Smart farming

- Food sustainability

- Sentiment analysis

- Public perception

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Investigating knowledge dissemination and social media use in the farming network to build trust in smart farming technology adoption

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing

ISSN : 0885-8624

Article publication date: 3 May 2023

Issue publication date: 27 June 2023

This paper aims to investigate how actors in the farmer’s network influence the adoption of smart farming technology (SFT) and to understand how social media affects this adoption process, in particular focusing on the influence of social media on trust in knowledge dissemination within the network.

Design/methodology/approach

The methodology used a two-stage process, with semi-structured interviews of farmers, augmented by a netnographic approach appropriate to the social media context.

The analysis illustrates the key role of the farmer network in the dissemination of SFT knowledge, bringing insight into an important B2B context. While social media emerges as a valuable way to connect farmers and promote discussion, it remains underused in knowledge dissemination on SFT. Also, farmers exhibit more trust in the content from peers online rather than from SFT vendors.

Originality/value

Novel insights are gained into the influence of the farming network on the accelerated adoption of SFT, including the potential role of social media in mitigating the homophilous nature of peer-to-peer interactions among farmers through exposure to more diverse actors and information. The use of a social network theory lens has provided new insights into the role of trust in shaping social media influence on the farmer, with variances in farmer trust of information from technology vendors and from peers.

- Technology adoption

- Social media

- Knowledge dissemination

- Smart farming technology

Dilleen, G. , Claffey, E. , Foley, A. and Doolin, K. (2023), "Investigating knowledge dissemination and social media use in the farming network to build trust in smart farming technology adoption", Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 38 No. 8, pp. 1754-1765. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2022-0060

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Grainne Dilleen, Ethel Claffey, Anthony Foley and Kevin Doolin.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial & non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Smart farming technology (SFT) has been identified as a panacea for many challenges faced by the agricultural sector ( Kernecker et al. , 2019 ). Analogous to deployment in an Industry 4.0 setting, SFT is information and communication technology incorporated into agricultural machinery, equipment and landscapes, thereby creating large volumes of data that farmers can use to optimise their operations ( Pivoto et al. , 2018 ). SFT facilitates a reduction in farmers’ usage of fertilisers/pesticides, lowering their environmental footprints whilst increasing yield output and saving time and money ( Hellin and Fisher, 2018 ). SFT enables farm-to-fork traceability, which directly addresses consumers’ food quality concerns whilst laying the groundwork for food security and sustainability through precision farming ( Ping et al. , 2018 ; Roussaki et al. , 2019 ). However, widespread adoption of SFT by farmers across Europe is yet to be achieved ( Barnes et al. , 2019a ; Pathak et al. , 2019 ).

This study addresses the need for scholarly insight into two important aspects of SFT adoption: 1. The role of the farmer network in SFT adoption . Understanding how and why farmers adopt SFT is central to successful technology deployment and uptake ( Kernecker et al. , 2019 ). This paper responds to the many calls ( Jayashankar et al. , 2018 ; Klerkx, 2021 ; Nordin et al. , 2021 ; Ofori and El-Gayar, 2020 ) in the extant literature for empirical research to investigate the role of the farmer’s network in influencing SFT adoption.

2. Social media (SM) influence on farmer adoption of SFT within the network . The dissemination of information or knowledge within agricultural extension models has traditionally been viewed as a linear process ( Röling, 1992 ). More recently, communication has moved towards being a dialogue between many actors, facilitated by SM ( Chowdhury and Hambly Odame, 2013 ). This study responds to the call to examine the deployment of SM in agriculture, in particular how SM influences farmers’ decisions and their adoption of technology ( Liu et al. , 2018 ; Philips et al. , 2018 ). With the exception of studies focusing on the operational benefits of enhanced information ( Sundström et al. , 2020 ), there has been a dearth of studies investigating the influence of SM on B2B relationships compared to business-to-consumer (B2C) relationships ( Asare et al. , 2016 ; Drummond et al. , 2020 ; Singaraju et al. , 2016 ). We propose that SM-enhanced knowledge dissemination through the network can influence the trust of the buyer in the credibility of the source ( Brennan and Croft, 2012 ; Zhang and Li, 2019 ), thereby increasing the intention of the farmer to adopt SFT.

Building on the premise in the technology adoption literature that adoption results from building networks of heterogenous associations, this research comprises an empirical study to address the following overarching questions: How does the farmer’s network influence SFT adoption? How does SM influence farmers’ adoption of SFT? What is the influence of SM on trust in knowledge dissemination within the network related to SFT?

We begin by reviewing the literature and presenting the theoretical framework. The composition of the farmer’s network, the farmer’s use of SM and its effect on their behaviour is discussed. The research methods adopted are described, followed by an analysis of the findings. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings, managerial implications, the limitations of the study and indications for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1 social networks and technology adoption.

Social behaviour comprises an exchange not just of material goods but also intangibles such as ego gratification, symbols, etc. ( Homans, 1958 ). A core feature is the concept of reciprocity, which underlies motivation in exchange relationships, where mutual gratification and contribution is anticipated ( Gouldner, 1960 ). Perhaps not surprisingly, reciprocity is critical in online SM interactions where one party contributing tokens of appreciation such as shares or likes of content is rewarded by the other party in a similar fashion ( Kim and Kim, 2021 ; Surma, 2016 ). Reciprocity and trust are critical elements of social exchange ( Mayer et al. , 1995 ; Putnam, 2000 ; Skaalsveen et al. , 2020 ) and significant influences on online group buying ( Shiau and Luo, 2012 ), which is relevant to the SFT purchasing context of this study.

Social networks are crucial in technology adoption, diffusion and innovation decisions ( Rampersad et al. , 2012 ), helping to transfer knowledge within and between organisations ( Marchiori and Franco, 2020 ; Massaro et al. , 2017 ). They also enable sense-making tasks, including a cost-benefit analysis regarding the effort and time associated with technology adoption ( Abbas et al. , 2018 ). A network is defined “by individual members (nodes) and the links among them through which information, money, goods or services flow” ( Maertens and Barrett, 2012 , p. 353). Links between nodes are represented by edges, while edge weights represent the frequency of information exchange and its influence ( Valujeva et al. , 2023 ).

Social network analysis (SNA) enables the identification of stakeholders within a network and understanding of the relationships and reciprocity between actors as well as their associated influence ( Valujeva et al. , 2023 ). SNA identifies two types of networks; a sociocentric network where the relationships between all actors are measured and an ego-centric network where the focus is on one individual and their relationships with other nodes ( Froehlich and Brouwer, 2021 ). This research focuses on the ego-centric network with the farmer representing the ego-centric node. When conducting SNA, three factors must be considered; social capital, homophily and contagion ( Froehlich and Brouwer, 2021 ). Social capital relates to resources available in the network, the individual’s position within the network and how involvement allows the person to reach their goals and fulfil objectives ( Han et al. , 2019 ). Trust between actors is a critical factor in the development of relationships and one of the most important measurements of social capital ( Inkpen and Tsang, 2005 ; Massaro et al. , 2017 ; Nosratabadi et al. , 2020 ). This trust is built on the individual’s perception of the benevolence, integrity and competency of the other actors in the network ( Mayer et al. , 1995 ) and is based on the concept of reciprocity ( Putnam, 2000 ). If the actors trust each other, there is more likely to be open communication and information sharing. However, Granovetter (1973) argues that weak ties or loose connections are also needed in the network to enable more diverse information exchange. Homophily describes the concept that people are more likely to develop relationships with those who share similar attitudes, values and opinions ( Kossinets and Watts, 2009 ). It is intensified by proximity, meaning that if actors are geographically or physically close to each other, they are more likely to form a relationship ( McPherson et al. , 2001 ). Lastly, contagion relates to the diffusion of information through the network ( Froehlich and Brouwer, 2021 ).

2.2 The farmer’s network

Farmers participate in interlinked networks composed of human and non-human entities ( Gray and Gibson, 2013 ) such as peer farmers, farm advisors, associations, cooperatives, material providers, vendors, agribusinesses, artifacts and organisational structures ( Jallow et al. , 2017 ; Joffre et al. , 2019 ; Klerkx, 2021 ). Although the network consists of multiple actors, the principle of homophily is evident with farmers mostly connecting with other farmers who they see as similar ( Phillips et al. , 2021 ). This network enables knowledge transfer, observation, advice seeking and sense checking regarding the procedures and technologies being adopted on the farm ( Chavas and Nauges, 2020 ; Joffre et al. , 2020 ; Pathak et al. , 2019 ). In-person connection is important when making a decision regarding the adoption of digital technologies, but digital communication sources are beneficial to learn about the benefits of such technologies ( Colussi et al. , 2022 ).

Interactions between farmers in the network are significant and influential, particularly regarding the adoption of SFT ( Blasch et al. , 2020 ; Knierim et al. , 2018 ). Farmers trust the information that other farmers with direct experience of using SFT share, due to their credibility and competency ( Rust et al. , 2021 ). However, Barnes et al. (2019b ) question the role of peer farmers due to the sophisticated technical nature of the decision. Accordingly, the debate regarding the influence of peer farmers in the adoption of SFT warrants further exploration. Farm advisors and agronomists play an important network role in diffusing information on SFT to farmers ( Eastwood et al. , 2019 ; Higgins and Bryant, 2020 ). Knierim et al. (2018) suggest that information received from farm advisors, who are independent from any company, is the most influential. However, many farm advisors struggle with constantly changing technologies and the associated data analysis required ( Nettle et al. , 2018 ), suggesting their role in facilitating SFT adoption is limited.

Technology vendors are seen as peripheral actors in the network, as farmers often feel the need to sense check the information received with peer farmers and advisors ( Hartwich et al. , 2007 ). Certainly, the adoption of SFT has been hampered by farmer uncertainty regarding the value of implementation, distrust of the technology vendor and scepticism ( Jakku et al. , 2019 ; Wolfert et al. , 2017 ). This is due to the perception that technology vendors overemphasise the benefits of technology implementation ( Jerhamre et al. , 2022 ). Thus, it is argued that trust in technology vendors is not as strong as other actors in the network.

2.3 The influence of social media on farmer smart farming technology adoption

The use of SM to discuss agricultural issues has become popular ( Ofori and El-Gayar, 2020 ), facilitating networking and knowledge exchange on farming practices and technologies ( Barrett and Rose, 2020 ; Morris and James, 2017 ; Philips et al. , 2018 ; Riley and Robertson, 2021 ; Skaalsveen et al. , 2020 ). This has been further heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic ( Colussi et al. , 2022 ). Farmers are participating in more farmer-to-farmer and farmer-to-rural professional conversations on Twitter ( Jiang et al. (2022) . In their study of farmers’ adoption of no-till farming practices, Skaalsveen et al. (2020) found that farmers favoured Twitter as a preferred means of SM communication as it enables easier peer interactions. Das et al. (2019) observed that farmers use Facebook and Twitter to learn more about new technologies, particularly those already using an existing SFT on farm. YouTube has enabled farmers to share videos of their practices as well as learning from other farmers, technology vendors and experts ( Burbi and Hartless Rose, 2016 ). WhatsApp has become popular with farmers creating or joining groups created by government or knowledge transfer bodies ( Colussi et al. , 2022 ; Vedeld et al. , 2020 ).

This increased use of SM is because of the ability to receive and share content, regardless of location and without the limitation of a traditional gatekeeper ( Ventura et al. , 2008 ). SM users’ pool of weak ties has increased, resulting in more diverse information being shared ( Grabner-Kräuter, 2010 ). As a result, SM has expanded the reach of the network considerably ( Drummond et al. , 2020 ) and allowed network actors to change their strategic roles or positions relevant to others ( Pardo et al. , 2022 ). Thus, Singaraju et al. (2016) deduce that SM platforms are examples of intermediary or bridging actors, connecting actors together. Highly influential SM users, or “influencers”, hold a critical position in the network, managing the flow of information ( Himelboim, 2017 ). Rust et al. (2021) note that farmer influencers have become important for sharing information. However, Kim and Kim (2021) identify the concept of perceived similarity between the influencer and the SM user as necessary in developing trust and reciprocity.

Alongside the positives associated with SM marketing and usage, the growth of digital content and the proliferation of fake news across digital platforms have made it difficult for farmers to ascertain which sources of information to trust ( Rust et al. , 2021 ). There is an abundance of low-value information, which often leads to users’ lack of trust and scepticism in the content ( Cao et al. , 2021 ). Sterrett et al. (2019) ascertain that the credibility, integrity and honesty of the person posting the content, as well as the platform used, is an indicator of whether people will view the information as trustworthy. If the online platform environment is considered helpful, trust in the content is more likely to exist ( Ebrahim, 2019 ). Nevertheless, platforms such as Twitter are subject to homophily; users and businesses are more likely to connect with and retweet content from users who share their own experiences and beliefs ( Himelboim et al. , 2017 ). Wang et al. (2020) also highlight that, as with other SM users, farmers often present a positive representation of themselves or “good farming” practices on SM, thereby filtering what they share online.

3. Methodology

Based on the preceding, this study adopted a two-stage approach. Personal interviews were selected as the main method to gain an in-depth understanding of the composition of the farmer’s network, the interactions between actors and the role that SM plays in SFT adoption. Netnography was then conducted to further explore the farmer’s network on SM and determine the content being shared. Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted with farmers across Europe, having judged that theoretical saturation had been achieved ( Saunders et al. , 2018 ). The number of interviews is in line with other studies exploring technology adoption in a farming context ( Higgins and Bryant, 2020 ; Jayashankar et al. , 2019 ; Regan, 2019 ; Skaalsveen et al. , 2020 ). A purposive sampling method was followed, and participants were recruited using email. The demographic profile of the farmers interviewed is available in Table 1 .

Interviews were online and lasted on average 35 min. Each interview was structured into three segments: understanding the farmer, exploring their knowledge and use of SFT and exploring their network and the influence of SM. Interviews were transcribed and reviewed to ensure accuracy. All identifying information was removed to protect the farmers’ identity. NVivo12 Plus was used to manage the qualitative data and assist in the analysis process. A thematic analysis was followed, which was consistent with the Braun and Clarke (2006) six-step framework. Anonymised quotes are used in the Findings and Discussion.

Netnography ( Kozinets, 2006 ) was then used to study the farmer’s network on Twitter and to analyse SM content. Twitter was chosen as the site of study as it is an open network and was mentioned frequently in the interviews. Various studies have validated the use of Twitter when observing B2B SM use ( Cripps et al. , 2020 ; Juntunen et al. , 2020 ). Twitter is also consistent with the recommendation of Kozinets et al. (2014) to select a field site that will help to answer the research questions and allow for rich data collection. An observational, non-participatory role was undertaken, where the Twitter posts and accounts followed were passively monitored. Archival data (pre-existing online), where the researchers were not active participants in its creation, were gathered in the form of text and visual posts. Costello et al. (2017) acknowledge that due to the volumes of data being explored in netnography, studies using the approach are unlikely to be both wide and deep. Consequently, four Twitter accounts of farmers in the UK and Ireland were analysed. Two accounts were from farmers interviewed (Irish dairy farmers) and two accounts were identified by other farmers in the interviews (UK beef and sheep farmer and Irish dairy farmer). None of these accounts was classified as influencers. The number of other Twitter accounts followed by the farmers analysed ranged from approximately 300–950. Firstly, an analysis was undertaken of the accounts the farmers followed on Twitter and categorised into different actor groups accordingly. These groups comprised farmers, advisory services (farm advisors, agronomists, vets and researchers), agricultural initiatives such as EU projects and development projects, agrimedia (agricultural journalists or agricultural publications), agri-business providers/employees, technology vendors/employees, government bodies, weather-related and “Other”, which consisted of non-farming-related accounts or accounts where there was no qualifying information in the Twitter biography. Next, content analysis of Twitter posts (native and retweets) from March–June 2022 was conducted. The information was exported into NVivo12, analysed and coded accordingly.

4. Findings

A sequential analysis strategy was undertaken with the interviews analysed first, followed by the netnographic analysis.

4.1 Farming in the business-to-business domain

All farmers identified their farm as a business, driven by the need to make profit, regardless of whether they had off-farm employment. For example, Farmer H stated, “the focus for my farm is economical”. Words like “enterprise”, “career” and “business owner” were used consistently by respondents throughout the interviews. Respondent A summarised their thoughts by saying “I think the broader picture is very much to look at farming as a business and every farmer, be they big or small, as a business owner”.

4.2 Use and benefits of smart farming technology

Adopters and non-adopters were positively disposed towards SFT. The noted benefits related to increased productivity, “An average cow milked 8 litres, now with the robot, they are milking 10 litres” (Respondent G), cost savings, “I’m saving on seeds and fertilizer, so you can see the economic benefits” (Respondent K) and labour savings. The use of SFT to deliver environmental sustainability was also cited as important, especially to deal with the increased climate change requirements. One farmer was clear however that he did not want technology to replace all labour, “Our culture is to get your hands dirty. Smart solutions can help with 80% of the work, but the rest should be according to touch and feel” (Respondent I). Respondents perceived that SFT was particularly relevant to dairy and tillage farming due to the larger farm size and their ability to invest. The majority of respondents felt that SFT was economically out of reach for the small-scale farmer. Equally, the location of the farm had an influence on adoption, “Autonomous tractors would be very useful in The Netherlands with flat land, not so much Spain” (Respondent M).

4.3 Actor engagement

The nodes in the farmer’s network comprised peer farmers (similar farm type and size), other farmers, farm advisory services, farming associations, agri-business suppliers, technology vendors and research institutes (albeit to a lesser degree). Frequent engagement with other network actors was important for all farmers, allowing them to gather information on SFT, learn from others’ experiences, solicit advice and sense-check decisions. As Respondent D stated, “There is a great saying in farming that you'll never learn anything inside your own gate”. Other farmers were the most preferred, frequently contacted and trusted source of information, “My first stop is progressive farmers in the locality” (Respondent N). This communication could take place in person, on the phone or using digital communication tools such as WhatsApp or Twitter, depending on where the farmer was located. Multiple farmers liked that SM allowed them to engage with a wider network of farmers in their own country and abroad, “It’s a useful way of learning, they post a photo, and you send a direct message” (Respondent R). Where possible, the respondents preferred to visit another farm to see the technology in operation, although videos on SM helped. Negative and positive reviews of SFT from other farmers in their network considerably influenced the farmer’s opinion of the technology.

The perception of the role of the farm advisor in SFT adoption was varied. Some farmers felt that advisors were a good resource, but their expertise lay in financial advice. Respondent C felt that advisors were not as knowledgeable about new technologies, “The fellas on YouTube are generally maybe a year or two ahead of advisors”. Formal groups such as the Irish Farmers’ Association (IFA), Coldiretti (Italy) or RegenAg (UK) were acknowledged as important for facilitating discussions on new farming practices and new technologies.

The majority of farmers were involved in a family farm but rarely discussed adopting technology with other family members. Such members were recognised as a key source of general farming information, but parents or older generations had limited exposure to technology and therefore were rarely consulted. Furthermore, a small number of farmers mentioned that they like to engage with researchers to allow them to gain new knowledge, which could lead to a competitive advantage.

4.4 Trust in the network

Peer farmers were the most trusted actors in the network, followed by other farmers and family members. This was due to their first-hand experience with technology (competency), and that they were more likely to “give an honest opinion” (integrity) (Respondent O). Farm advisors and farming associations were also seen as having the farmer’s interests at heart (benevolence) and therefore afforded a strong level of trust. Trust in agri-businesses and technology vendors varied, “same as any other sales company, some good, some bad, you have to do your own background checks and make sure they have a good history” (Respondent E). The distrust stemmed from three sources; the perception of being oversold the technology, the provider’s ability to deal with any technical issues encountered and uncertainty regarding the use of data generated from these technologies. Respondent K was very clear, “they <technology provider> start to speak about the economic benefits, but they have no idea how to harvest, to cultivate the land- so I just don’t trust them”. Having a provider located close to the farm was important to many farmers, “if there is a provider close to me, that can support me easily, then I will trust them” (Respondent M). The use of data split respondents’ opinions. Some were happy to share data provided there was a benefit for them, while others felt there should be agreements in place clearly specifying how the data is being used.

4.5 Social media and digital communication channels

SM channels were used by all respondents although they varied in their approach, with some taking an active role creating content while others perused information. YouTube was the most popular forum, although users mostly viewed information rather than having their own account. Facebook was the next most popular; however, it was used more as a personal SM forum rather than for farming content. Next was Twitter, followed by LinkedIn and then Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok. Several respondents had developed business SM accounts for the farm and used their personal channels to share information. One farmer was using Facebook as a sales tool to sell animals to other farmers, while another was using Instagram as a promotional tool to attract consumers directly.

Farming press was identified as a good source of information on SFT, as were online sites and farming programmes on the radio. Many of these channels also recommended or directed to relevant SM accounts for more information. Therefore, SM was emphasised as a relevant source of information when learning about SFT, enabling the farmer to compare their farm against others, “You can go on and see what the farmers in United States are talking about in technology terms” (Respondent H). However, the downside was the time needed to explore information or create relevant content for their own accounts. Digital communication tools such as WhatsApp, email and specialised online fora were also popular.

4.6 Information search, sense making and networking on social media

Respondents followed several different SM accounts ranging from farmers they knew, farmers running similar farm types, high profile or “influencer” type farmers, knowledge transfer groups, agrimedia, as well as technology vendors. The location of the account was not important. Twitter was recognised as a great source to learn about new technologies, while YouTube was highlighted as good for learning about certain brands and their features. SM was also popular in helping to address problems or queries relating to technology and farming practices. Respondent D outlined, “you’ll have a reply instantly. You could have six different pieces of advice, with six different people within a blink of an eye”. Twitter was also mentioned as a good forum to raise questions about a technology, “I might contact whoever I saw tweeting about or writing about it directly and just ask like well, can you give us a bit of an insight or share some experience” (Respondent A). YouTube also helped in terms of providing videos about how to use a particular SFT.

One of the major benefits of SM recognised by all respondents was its ability to facilitate connections with other farmers. “I really like the reach” said Respondent S, while Respondent D commented “Twitter, I suppose its inundated with farmers, its nearly become like an agricultural network”. It allowed them to communicate with other farmers outside their locality, ask advice and peruse other’s experiences.

4.7 Trust in social media content

Overall, respondents were in general somewhat distrusting of the content viewed on SM. Respondent S outlined, “I don’t trust social media, but I use it to give some light about what I need to find out more about”. The distrust was due to disinformation being shared or the inability to filter information. The platform was also seen as important as one respondent indicated that the negative always wins, especially on Twitter. Multiple farmers mentioned taking the conversation offline to validate the information received.

The level of trust in the SM content depended on the source, as Respondent Q acknowledged “It depends on who is providing the info, maybe for reputable sources”. Farmers were more likely to trust information from other farmers on SM, “if I see another farmer tweeting about it then that's one thing, if I see a company tweeting about it who are selling it than that's a different thing” (Respondent A). Information provided by farmers on SM was useful to then compare with their own context. High-profile influencer farmers were seen as a relevant source of information, “I follow a few farmers on YouTube and generally they kind of get free demonstrations, or free samples or free demos, and I suppose you become aware of the name” (Respondent C). However, respondents were not always as trusting in the content due to sponsored deals. “Farmers like me” (Respondent N) were seen as more influential. Farmers mostly trusted the information posted by agricultural groups and agrimedia on SM but would need to validate it themselves with additional research. Posts by SFT vendors were in general not trusted as the perception was that farmers were being sold to and the content was overinflated. The benevolence and integrity of the vendors was called into question.

4.8 Netnographic analysis

The netnographic analysis showed that the farmer’s network on Twitter comprised of both personal and business actors. Across the four accounts analysed, the top three actor categories followed were Farmers, Other and Advisory services. Farmers were consistently the highest group representing between 33% and 43% of the accounts that the farmers followed. This included peer farmers in terms of type of farm, farmers from other farm types, farmers from the same country, farmers from abroad and high-profile or influencer-type farmers. Within this farmer category, farmers from the same farm type accounted for the highest percentage. The next most popular category was Other, which represented between 23% and 39% of accounts followed. Advisory services accounted for 8%–14%, while agricultural initiatives varied between 2% and 9%. Agri-businesses represented 3%–7% of the accounts followed, while technology vendors were not major actor groups, accounting for less than 3%. In some instances, farmers followed a particular employee of the agri-business or SFT vendor, increasing their representation. Government actors consistently represented a small percentage of approximately 1%–2% of accounts followed.

In terms of content shared across the farmer’s SM accounts, it varied considerably. Most commonly, it showed images of work being conducted on farm such as harvesting, preparing bedding and milking, alongside images of animals or the fields. Environmental discussions were also prominent, given the timing of the analysis when the debate around the need for the agricultural sector to reduce carbon emissions was in the public domain. Retweets from other farmers, agrimedia publications, farming events and non-farming-related content were popular. To a lesser extent, content regarding farm machinery and technology such as tractors and automatic calf feeders was posted by farmers. Occasionally, farmers tweeted questions looking for advice on animals, the cost of inputs and recommendations on technology to deploy. Most of the engagement on the Twitter posts was farmer-to-farmer led, with other farmers posting their experiences or questions under the original post. Advisory services and initiatives occasionally interacted with links to articles and relevant information. Infrequently, farmers shared and commented on posts from technology vendors who were running a competition/giveaway.

5. Discussion

This research supports and enriches the existing discourse pertaining to technology adoption within an agricultural context. The findings suggest that exploring the influence of SM and the farmers’ network on the SFT adoption decision in a B2B context is needed. Farmers, regardless of farm size, herd size or off-farm employment, clearly identify as business owners. This supports the literature, which outlines that increasingly farmers see themselves as businesspeople or entrepreneurs rather than the traditional producer-farmer identity ( Couzy and Dockes, 2008 ; Vesala and Vesala, 2010 ). SFT adoption has been cited as being crucial to improving agricultural sustainability, lowering its associated environmental footprint and increasing productivity ( Islam et al. , 2021 ). Results from this study suggest that farmers recognise the benefits of SFT adoption and are interested in learning more about the advantages and challenges of implementation. Thus, understanding the role of the business network and how digital communication tools such as SM can facilitate SFT adoption is timely.

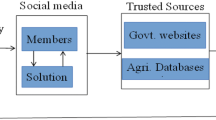

Overall, the results indicate that the farmer’s network is essential in the dissemination of information relating to SFT and plays an important sense-checking role. As outlined in the conceptual diagram in Figure 1 , the overall network is heterogenous in nature with multiple actors involved, with varying levels of influence. Peer and other farmers are the most important actors due to the level of trust and reciprocity they are afforded. The concept of social capital is important as farmers trust the information, both positive and negative, that other farmers share about technology due to their perceived competency and integrity. This directly contradicts Barnes et al. (2019b ) who question the role that farmer-to-farmer networks play in SFT adoption due to the technology’s high cost and sophisticated nature. It supports previous theoretical and empirical work that highlights the importance that farmers place on other farmers’ opinions ( Blasch et al. , 2020 ; Knierim et al. , 2018 ). However, local peer farmers constitute a large portion of the farmer’s offline network, suggesting that an element of homophily is evident, which can limit the diffusion of information and subsequent adoption of technology. SM is an important bridging actor in the network, introducing more weak ties and thus more diverse information related to SFT, and increasing the heterogenous nature of the network. Fisher et al. (2018) determine that heterophilous networks are important in creating awareness of innovative technology while homophilous networks help with adoption. Therefore, further diversifying the farmer’s online network could result in an increased understanding of SFT. Other actors in the network such as vendors, advisory services and agrimedia publications play a pivotal role in introducing new actors to the farmer’s network.

Eastwood et al . (2017) highlighted the importance of farm advisors and extension agents in sharing knowledge on SFT. Interviewed farmers stated that although farm advisors are important and trusted actors in the network, in relation to SFT adoption, their role is not always as influential. This was bolstered by the netnographic analysis, which showed that advisory services only represented between 8% and 10% of the accounts that the farmers followed on Twitter. These findings support Higgins and Bryant (2020) who posit that advisors play a limited role in providing SFT advice to farmers. This suggests that there is a need for advisors to upskill on SFT and then proactively share and promote this information. Demonstration events of SFT on farms, facilitated by advisors, could help to change the perception that they are lagging behind with regard to new technologies. Results from the interviews suggest that actors such as agronomists, farming associations and research institutes have an adequate presence on Twitter and are important in sharing new knowledge. Increased interaction between these trusted bodies and farmers on SM could result in a wider dissemination of knowledge.

Findings from this research provide empirical evidence supporting the viewpoint that SM is an important tool to share knowledge and experiences ( Barrett and Rose, 2020 ; Mills et al. , 2019 ). SM facilitates multiple exposures to farming and SFT information, which is necessary for social contagion or the adequate diffusion of information. The level of SFT information being shared on SM is however relatively limited. Farmers are more likely to post about their day-to-day work and share images of their farming activities than the technology in operation. Phone calls, face-to-face discussions and digital communication through specialised fora and one-to-one conversations are still the preferred method of communication. This supports Morris and James (2017) who deduce that SM in the agricultural sector has not reached its full potential. SM, therefore, is an untapped resource which actors in the farmer’s network can use to increase interactions. Farmer discussion groups and meetings, which discuss new practices and technologies, could be videoed and shared across SM, increasing the reach of the dissemination activities. Equally, agrimedia publications can also facilitate the dissemination of SFT knowledge by sharing relevant news stories, opinion pieces and features by farmers.

Results concur with Riley and Robertson (2021) who highlight that SM connects farmers, thereby widening their network. The study outlines how information from the network is generally trusted, but trust in SM information depends on the source and the platform used. Early adopters of technology are often seen as influencers and tend to be more active on SM ( Skaalsveen et al. , 2020 ). Both the netnographic analysis and the conducted interviews confirm that farmers followed such influential or high-profile farmers across SM. Following these accounts facilitated the awareness of new technologies and learning of specific features and benefits. Micro-influencers or small-scale influencers were also popular and in general more trusted. Leveraging “everyday” farmers and micro-influencers to produce user-generated content, particularly on Twitter and YouTube, could further raise the profile of SFT once the content was seen as authentic and transparent.

Results suggest that farmers are trusting of technology but more sceptical of SFT vendors and their SM content due to the perception of being “over sold” to or “over-promising”. As highlighted in previous research, trust in B2B relationships is important to minimise concerns and vulnerability associated with adoption ( Jayashankar et al. , 2018 ). To improve this relationship, SFT vendors need to be more vocal with structural assurances such as guarantees and regulations to alleviate potential concerns. In addition, issues relating to data governance and data sovereignty divide thinking. Some farmers were concerned with the lack of transparency regarding data management, while others believe it is part of using the technology. This is somewhat consistent with findings from Wiseman et al. (2019) who find that farmers’ lack of trust in SFT is often linked to uncertainty regarding how the provider is managing the data generated. Clearly communicating how the data is being used in a non-technical manner to farmers could alleviate their concerns. Furthermore, conducting interviews on SM with “everyday” farmers who are using SFT could help to build trust.

Crucially, the results imply that although SM is beneficial in sharing knowledge and sense-checking information, its role in persuading the adoption of SFT is limited. The adoption decision is more influenced through offline connections in the network. However, awareness is a prerequisite for adopting technology ( Dessart et al. , 2019 ). Ineffective communication of an innovation leads to a lack of awareness, resulting in failed diffusion and lower rates of adoption ( Rogers, 2003 ). Awareness of SFT is relatively limited as the market launch is recent ( Knierim et al. , 2018 ). Thus, encouraging more SM content and interaction regarding SFT is a key step towards ensuring social contagion.

6. Conclusion and implications

6.1 theoretical implications.

This study set out to investigate the influence of the farmer’s network on the adoption of SFT. There are two main theoretical contributions. Firstly, the study is rooted in social network theory, providing fresh empirical insight into the influence of the farming network on the accelerated adoption of SFT ( Jayashankar et al. , 2018 ; Joffre et al. , 2020 ; Klerkx, 2021 ; Nordin et al. , 2021 ; Ofori and El-Gayar, 2020 ) and finds that the farmer’s network is heterogeneous in nature, with a number of actors with various levels of influence on the farmer’s SFT adoption process. However, homophily is evident in peer farmer interaction, but the use of SM as a bridging actor introduces more diverse actors and information into the network. However, SM is being underutilised for sharing SFT knowledge, demonstrating the need for increased interaction between actors. Secondly, this study has provided new insights into the role of trust, which emerged as a significant influence on adoption and knowledge dissemination. In contrast to Barnes et al. (2019a , 2019b ), the study found that farmers trust their peers when it comes to technology, while remaining sceptical about technology vendors. We provide empirical support for Barrett and Rose (2020) and Mills et al. (2019) through critical insights into the role of trust in shaping SM influence on the farmer ( Rust et al. , 2021 ; Zhang and Li, 2019 ). Lastly, this study, in identifying the role of SM within the farming network for sharing knowledge and experience, addresses the calls for more research to understand the influence of SM on businesses’ decisions and practices ( Asare et al. , 2016 ; Drummond et al. , 2018 ) ( Morris and James, 2017 ).

6.2 Managerial implications

The findings of this study have implications in B2B marketing within the SFT domain. SM has the power to fully transform the agri-tech communications landscape, as shown in the schematic in Figure 2 .

SFT vendors should invest further in SM to engage farmers. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube have been identified as important sources of information to learn about new SFT. Vendors must go beyond implementing a purely informational platform by engaging in multi-directional dialogues with multiple actors in the farmer’s network. Information transparency is key to gaining farmers’ trust in SFT vendor SM posts, especially sponsored content, or endorsements. Sentiment analysis provides an automated means for vendors to truly understand what their customers are saying about them online and is a tool that should not be underestimated. Additionally, conversational dissemination, driven by responsive agents and close-to-human AI bot technologies, is key to driving meaningful engagement and conversation.

Findings indicate that technology vendors should provide processes to support social bonds that may develop among farmers. In particular, fostering of virtual communities hosted by appropriate vendors and agencies would further develop confidence and trust in SFT adoption. Encouraging and incentivising actors, particularly peer farmers and micro-influencer farmers, to act as advocates or brand ambassadors is an important step in this process, with the caveat that information transparency is crucial. This is critical if the agricultural sector is to meet its sustainability goals across the next 20 years.

The research also has implications for farm advisory services, research institutes and agrimedia publications. The research suggests that these organisations need to ensure that they spend adequate time on SM diffusing SFT information and engaging in dialogue with farmers. Questions and answers sessions using online tools such as Facebook Live and Twitter Spaces could give an opportunity to farmers to learn about SFT and also sense-check their concerns. Key to this is demonstrable value creation arising from the adoption of SFT in multiple contexts.

Lastly, not all farmers are proficient in using SM; further education and training could be provided on how these platforms can assist their business further, such as using it for sales purposes, developing business relationships and expanding their network, driving heterophily. Farm advisory services and knowledge transfer agents are central to delivering this training. This also raises the important contribution that could be made through supporting farmers to embrace technology and therefore benefit from the advantages, which will percolate through society.

7. Limitations

While the qualitative approach to the research helped to build up a rich profile of the network effects on farmer adoption of SFT, the results from the semi-structured interviews are exploratory in nature. Further research is required to quantify the role of the network in promoting or inhibiting farmer adoption of SFT. This could take the form of a survey of farmers in the EU using measures of constructs that were explored in this study. Future netnographic studies could take an active engagement role on Twitter or a virtual community to monitor discussions and interactions.

Conceptual diagram of the farmer’s network and influence strength

Transforming conversations through SM and virtual communities

Demographic profile of respondents

| Age | Gender | Farm type | Farm location | Full time (FT)/part time (PT) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | M | Sheep | Ireland | PT | |

| 40 | M | Dairy | Ireland | FT | |

| 42 | M | Beef to calf | Ireland | PT | |

| 32 | F | Dairy | Ireland | FT | |

| 36 | M | Dairy | Ireland | FT | |

| 24 | F | Dairy | Ireland | FT | |

| 45 | M | Dairy | Norway | PT | |

| 35 | M | Arable | Romania | FT | |

| 28 | M | Vine growing | Georgia | PT | |

| 26 | F | Beef and arable | UK | PT | |

| 26 | F | Arable | Italy | FT | |

| 36 | M | Potato | The Netherlands | FT | |

| 45 | M | Arable and olive | Spain | PT | |

| 27 | F | Dairy and beef | Ireland | FT | |

| 25 | F | Dairy | Ireland | PT | |

| 57 | M | Vine growing | Montenegro | PT | |

| 40 | M | Orchard/fruit | Montenegro | PT | |

| 41 | M | Arable | Romania | FT | |

| 43 | M | Vine growing | Portugal | FT | |

| 45 | M | Orchard/fruit | Georgia | FT |

Authors’ own work

Abbas , A. , Zhou , Y. , Deng , S. and Zhang , P. ( 2018 ), “ Text analytics to support sense-making in social media: a Language-Action perspective ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 42 No. 2 , pp. 427 - 464 .

Asare , A.K. , Brashear-Alejandro , T.G. and Kang , J. ( 2016 ), “ B2B technology adoption in customer driven supply chains ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 12 .

Barnes , A.P. , Soto , I. , Eory , V. , Beck , B. , Balafoutis , A. , Sánchez , B. , Vangeyte , J. , Fountas , S. , van der Wal , T. and Gómez-Barbero , M. ( 2019a ), “ Exploring the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: a cross regional study of EU farmers ”, Land Use Policy , Vol. 80 , pp. 163 - 174 .

Barnes , A.P. , Soto , I. , Eory , V. , Beck , B. , Balafoutis , A.T. , Sanchez , B. , Vangeyte , J. , Fountas , S. , van der Wal , T. and Gómez-Barbero , M. ( 2019b ), “ Influencing incentives for precision agricultural technologies within European arable farming systems ”, Environmental Science & Policy , Vol. 93 , pp. 66 - 74 .

Barrett , H. and Rose , D.C. ( 2020 ), “ Perceptions of the fourth agricultural revolution: what’s in, what’s out, and what consequences are anticipated? ”, Sociologia Ruralis , Vol. 62 No. 2 , pp. 162 - 189 .

Blasch , J. , van der Kroon , B. , van Beukering , P. , Munster , R. , Fabiani , S. , Nino , P. and Vanino , S. ( 2020 ), “ Farmer preferences for adopting precision farming technologies: a case study from Italy ”, European Review of Agricultural Economics , Vol. 49 No. 1 , pp. 33 - 81 .

Braun , V. and Clarke , V. ( 2006 ), “ Using thematic analysis in psychology ”, Qualitative Research in Psychology , Vol. 3 No. 2 , pp. 77 - 101 .

Brennan , R. and Croft , R. ( 2012 ), “ The use of social media in B2B marketing and branding: an exploratory study ”, Journal of Customer Behaviour , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 101 - 115 .

Burbi , S. and Hartless Rose , K. ( 2016 ), “ The role of internet and social media in the diffusion of knowledge and innovation among farmers ”, paper presented at International Farming Association (IFSA) Symposium , Newport , 12-15 July .

Cao , D. , Meadows , M. , Wong , D. and Xia , S. ( 2021 ), “ Understanding consumers’ social media engagement behaviour: an examination of the moderation effect of social media context ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 122 , pp. 835 - 846 .

Chavas , J.P. and Nauges , C. ( 2020 ), “ Uncertainty, learning, and technology adoption in agriculture ”, Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy , Vol. 42 No. 1 , pp. 42 - 53 .

Chowdhury , A. and Hambly Odame , H. ( 2013 ), “ Social media for enhancing innovation in agri-food and rural development: current dynamics in Ontario, Canada ”, The Journal of Rural and Community Development , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 97 - 119 .

Colussi , J. , Morgan , E.L. , Schnitkey , G.D. and Padula , A.D. ( 2022 ), “ How communication affects the adoption of digital technologies in soybean production: a survey in Brazil ”, Agriculture , Vol. 12 No. 5 , pp. 1 - 24 .

Costello , L. , McDermott , M.-L. and Wallace , R. ( 2017 ), “ Netnography: range of practices, misperceptions, and missed opportunities ”, International Journal of Qualitative Methods , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 12 .

Couzy , C. and Dockes , A.-C. ( 2008 ), “ Are farmers businesspeople? Highlighting transformations in the profession of farmers in France ”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 407 - 420 .

Cripps , H. , Singh , A. , Mejtoft , T. and Salo , J. ( 2020 ), “ The use of twitter for innovation in business markets ”, Marketing Intelligence & Planning , Vol. 38 No. 5 , pp. 587 - 601 .

Das , J.V. , Sharma , S. and Kaushik , A. ( 2019 ), “ Views of Irish farmers on smart farming technologies: an observational study ”, Agri Engineering , Vol. 1 No. 2 , pp. 164 - 187 .

Dessart , F.J. , Barreiro-Hurlé , J. and van Bavel , R. ( 2019 ), “ Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: a policy-oriented review ”, European Review of Agricultural Economics , Vol. 46 No. 3 , pp. 417 - 471 .

Drummond , C. , McGrath , H. and O'Toole , T. ( 2018 ), “ The impact of social media on resource mobilisation in entrepreneurial firms ”, Industrial Marketing Management , Vol. 70 , pp. 68 - 89 .

Drummond , C. , O'Toole , T. and McGrath , H. ( 2020 ), “ Digital engagement strategies and tactics in social media marketing ”, European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 54 No. 6 , pp. 1247 - 1280 .

Eastwood , C. , Klerkx , L. and Nettle , R. ( 2017 ), “ Dynamics and distribution of public and private research and extension roles for technological innovation and diffusion: case studies of the implementation and adaptation of precision farming technologies ”, Journal of Rural Studies , Vol. 49 , pp. 1 - 12 .

Eastwood , C. , Ayre , M. , Nettle , R. and Dela Rue , B. ( 2019 ), “ Making sense in the cloud: farm advisory services in a smart farming future ”, NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences , Vol. 90-91 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 10 .

Ebrahim , R.S. ( 2019 ), “ The role of trust in understanding the impact of social media marketing on brand equity and brand loyalty ”, Journal of Relationship Marketing , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 287 - 308 .

Fisher , M. , Holden , S.T. , Thierfelder , C. and Katengeza , S.P. ( 2018 ), “ Awareness and adoption of conservation agriculture in Malawi: what difference can farmer-to-farmer extension make? ”, International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 310 - 325 .

Froehlich , D.E. and Brouwer , J. ( 2021 ), “ Social network analysis as mixed analysis ”, The Routledge Reviewer's Guide to Mixed Methods Analysis , Routledge , London , pp. 209 - 218 .

Gouldner , A.W. ( 1960 ), “ The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement ”, American Sociological Review , Vol. 25 No. 2 , pp. 161 - 178 .

Grabner-Kräuter , S. ( 2010 ), “ Web 2.0 social networks: the role of trust ”, Journal of Business Ethics , Vol. 90 No. S4 , pp. 505 - 522 .

Granovetter , M.S. ( 1973 ), “ The strength of weak ties ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 78 No. 6 , pp. 1360 - 1380 .

Gray , B.J. and Gibson , J.W. ( 2013 ), “ Actor-Networks, farmer decisions, and identity ”, Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment , Vol. 35 No. 2 , pp. 82 - 101 .

Han , S-h. , Chae , C. and Passmore , D.L. ( 2019 ), “ Social network analysis and social capital in human resource development research: a practical introduction to R use ”, Human Resource Development Quarterly , Vol. 30 No. 2 , pp. 219 - 243 .

Hartwich , F. , Pérez , M.M. , Ramos , L.A. and Soto , J.L. ( 2007 ), “ Knowledge management for agricultural innovation: lessons from networking efforts in the bolivian agricultural technology system ”, Knowledge Management for Development Journal , Vol. 3 No. 2 , pp. 21 - 37 .

Hellin , J. and Fisher , E. ( 2018 ), “ Building pathways out of poverty through climate smart agriculture and effective targeting ”, Development in Practice , Vol. 28 No. 7 , pp. 974 - 979 .

Higgins , V. and Bryant , M. ( 2020 ), “ Framing agri‐digital governance: industry stakeholders, technological frames and smart farming implementation ”, Sociologia Ruralis , Vol. 60 No. 2 , pp. 438 - 457 .

Himelboim , I. ( 2017 ), “ Social network analysis (social media) ”, in Matthes , J. , Davis , C.S. and Potter , R.F. (Eds), The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods , John Wiley & Sons , New York, NY , pp, pp. 1 .- 15 .

Himelboim , I. , Smith , M.A. , Rainie , L. , Shneiderman , B. and Espina , C. ( 2017 ), “ Classifying twitter Topic-Networks using social network analysis ”, Social Media + Society , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 .

Homans , G.C. ( 1958 ), “ Social behavior as exchange ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 63 No. 6 , pp. 597 - 606 .

Inkpen , A.C. and Tsang , E.W.K. ( 2005 ), “ Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 30 No. 1 , pp. 146 - 165 .

Islam , N. , Rashid , M.M. , Pasandideh , F. , Ray , B. , Moore , S. and Kadel , R. ( 2021 ), “ A review of applications and communication technologies for internet of things (IoT) and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) based sustainable smart farming ”, Sustainability , Vol. 13 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 20 .

Jakku , E. , Taylor , B. , Fleming , A. , Mason , C. , Fielke , S. , Sounness , C. and Thorburn , P. ( 2019 ), “ If they don’t tell us what they do with it, why would we trust them?” Trust, transparency and benefit-sharing in smart farming ”, NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences , Vol. 90-91 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 .

Jallow , M.F.A. , Awadh , D.G. , Albaho , M.S. , Devi , V.Y. and Thomas , B.M. ( 2017 ), “ Pesticide risk behaviors and factors influencing pesticide use among farmers in Kuwait ”, Science of the Total Environment , Vol. 574 , pp. 490 - 498 .

Jayashankar , P. , Johnston , W.J. , Nilakanta , S. and Burres , R. ( 2019 ), “ Co-creation of value-in-use through big data technology – a B2B agricultural perspective ”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing , Vol. 35 No. 3 , pp. 508 - 523 .