Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Who Was Virginia Woolf?

Born into a privileged English household in 1882, author Virginia Woolf was raised by free-thinking parents. She began writing as a young girl and published her first novel, The Voyage Out , in 1915. She wrote modernist classics including Mrs. Dallowa y, To the Lighthouse and Orlando , as well as pioneering feminist works, A Room of One's Own and Three Guineas . In her personal life, she suffered bouts of deep depression. She committed suicide in 1941, at the age of 59.

Born on January 25, 1882, Adeline Virginia Stephen was raised in a remarkable household. Her father, Sir Leslie Stephen, was a historian and author, as well as one of the most prominent figures in the golden age of mountaineering. Woolf’s mother, Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson), had been born in India and later served as a model for several Pre-Raphaelite painters. She was also a nurse and wrote a book on the profession. Both of her parents had been married and widowed before marrying each other. Woolf had three full siblings — Thoby, Vanessa and Adrian — and four half-siblings — Laura Makepeace Stephen and George, Gerald and Stella Duckworth. The eight children lived under one roof at 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington.

Two of Woolf’s brothers had been educated at Cambridge, but all the girls were taught at home and utilized the splendid confines of the family’s lush Victorian library. Moreover, Woolf’s parents were extremely well connected, both socially and artistically. Her father was a friend to William Thackeray, the father of his first wife who died unexpectedly, and George Henry Lewes, as well as many other noted thinkers. Her mother’s aunt was the famous 19th century photographer Julia Margaret Cameron.

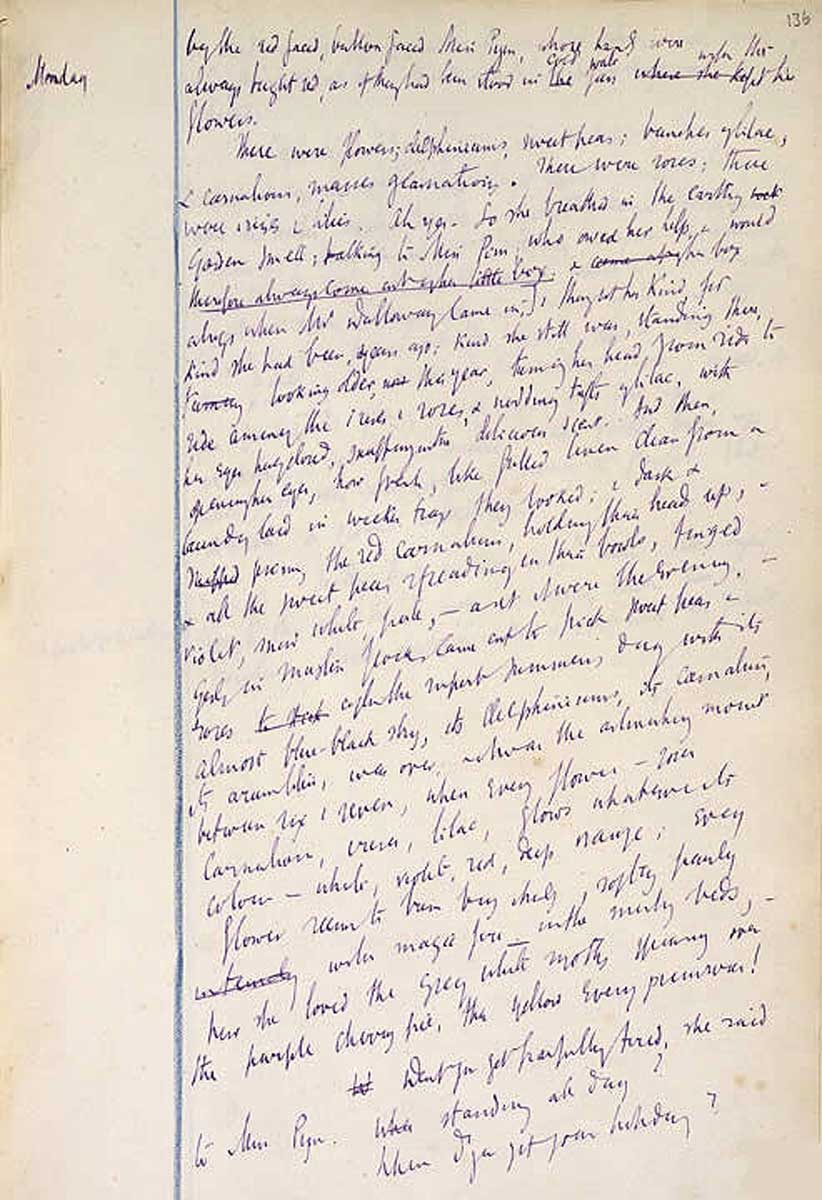

From the time of her birth until 1895, Woolf spent her summers in St. Ives, a beach town at the very southwestern tip of England. The Stephens’ summer home, Talland House, which is still standing today, looks out at the dramatic Porthminster Bay and has a view of the Godrevy Lighthouse, which inspired her writing. In her later memoirs, Woolf recalled St. Ives with a great fondness. In fact, she incorporated scenes from those early summers into her modernist novel, To the Lighthouse (1927).

As a young girl, Virginia was curious, light-hearted and playful. She started a family newspaper, the Hyde Park Gate News , to document her family’s humorous anecdotes. However, early traumas darkened her childhood, including being sexually abused by her half-brothers George and Gerald Duckworth, which she wrote about in her essays A Sketch of the Past and 22 Hyde Park Gate . In 1895, at the age of 13, she also had to cope with the sudden death of her mother from rheumatic fever, which led to her first mental breakdown, and the loss of her half-sister Stella, who had become the head of the household, two years later.

While dealing with her personal losses, Woolf continued her studies in German, Greek and Latin at the Ladies’ Department of King’s College London. Her four years of study introduced her to a handful of radical feminists at the helm of educational reforms. In 1904, her father died from stomach cancer, which contributed to another emotional setback that led to Woolf being institutionalized for a brief period. Virginia Woolf’s dance between literary expression and personal desolation would continue for the rest of her life. In 1905, she began writing professionally as a contributor for The Times Literary Supplement . A year later, Woolf's 26-year-old brother Thoby died from typhoid fever after a family trip to Greece.

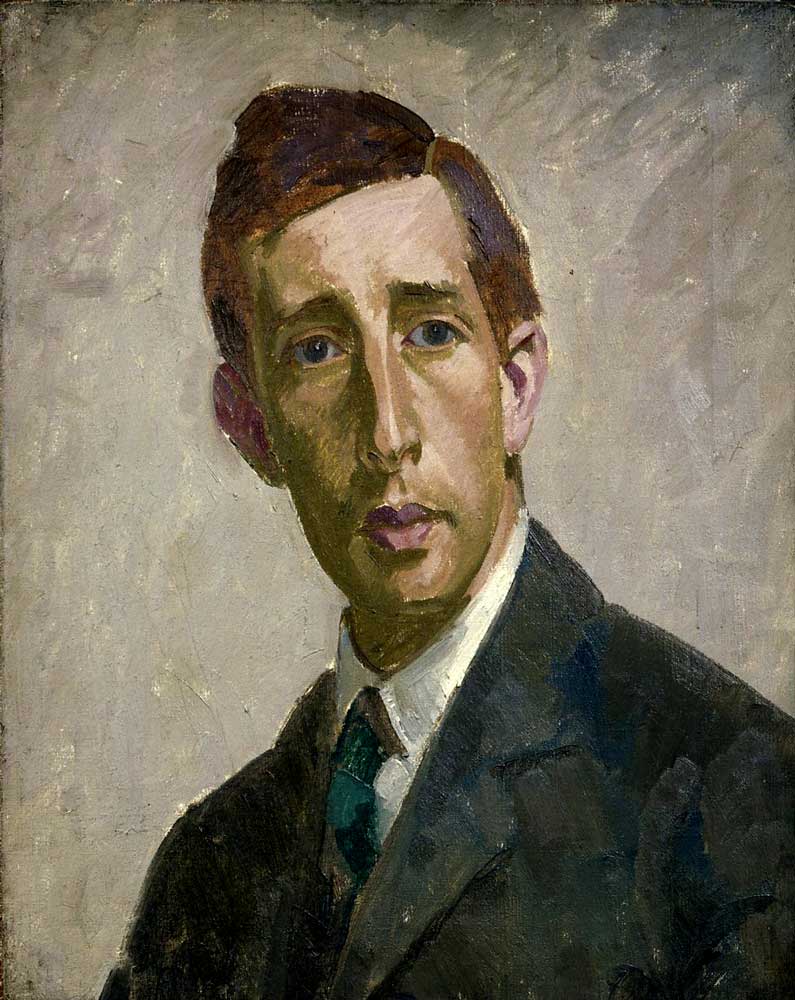

After their father's death, Woolf's sister Vanessa and brother Adrian sold the family home in Hyde Park Gate, and purchased a house in the Bloomsbury area of London. During this period, Virginia met several members of the Bloomsbury Group, a circle of intellectuals and artists including the art critic Clive Bell, who married Virginia's sister Vanessa, the novelist E.M. Forster, the painter Duncan Grant, the biographer Lytton Strachey, economist John Maynard Keynes and essayist Leonard Woolf, among others. The group became famous in 1910 for the Dreadnought Hoax, a practical joke in which members of the group dressed up as a delegation of Ethiopian royals, including Virginia disguised as a bearded man, and successfully persuaded the English Royal Navy to show them their warship, the HMS Dreadnought . After the outrageous act, Leonard Woolf and Virginia became closer, and eventually they were married on August 10, 1912. The two shared a passionate love for one another for the rest of their lives.

Literary Work

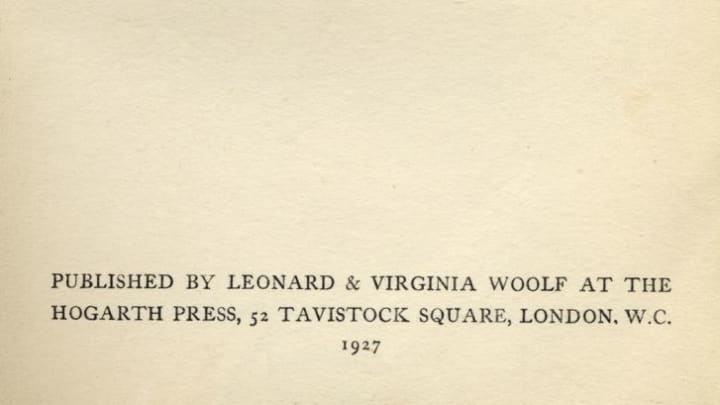

Several years before marrying Leonard, Virginia had begun working on her first novel. The original title was Melymbrosia . After nine years and innumerable drafts, it was released in 1915 as The Voyage Out. Woolf used the book to experiment with several literary tools, including compelling and unusual narrative perspectives, dream-states and free association prose. Two years later, the Woolfs bought a used printing press and established Hogarth Press, their own publishing house operated out of their home, Hogarth House. Virginia and Leonard published some of their writing, as well as the work of Sigmund Freud, Katharine Mansfield and T.S. Eliot.

A year after the end of World War I, the Woolfs purchased Monk's House, a cottage in the village of Rodmell in 1919, and that same year Virginia published Night and Day , a novel set in Edwardian England. Her third novel Jacob's Room was published by Hogarth in 1922. Based on her brother Thoby, it was considered a significant departure from her earlier novels with its modernist elements. That year, she met author, poet and landscape gardener Vita Sackville-West, the wife of English diplomat Harold Nicolson. Virginia and Vita began a friendship that developed into a romantic affair. Although their affair eventually ended, they remained friends until Virginia Woolf's death.

In 1925, Woolf received rave reviews for Mrs. Dalloway , her fourth novel. The mesmerizing story interweaved interior monologues and raised issues of feminism, mental illness and homosexuality in post-World War I England. Mrs. Dalloway was adapted into a 1997 film, starring Vanessa Redgrave, and inspired The Hours , a 1998 novel by Michael Cunningham and a 2002 film adaptation. Her 1928 novel, To the Lighthouse , was another critical success and considered revolutionary for its stream of consciousness storytelling.The modernist classic examines the subtext of human relationships through the lives of the Ramsay family as they vacation on the Isle of Skye in Scotland.

Woolf found a literary muse in Sackville-West, the inspiration for Woolf's 1928 novel Orlando , which follows an English nobleman who mysteriously becomes a woman at the age of 30 and lives on for over three centuries of English history. The novel was a breakthrough for Woolf who received critical praise for the groundbreaking work, as well as a newfound level of popularity.

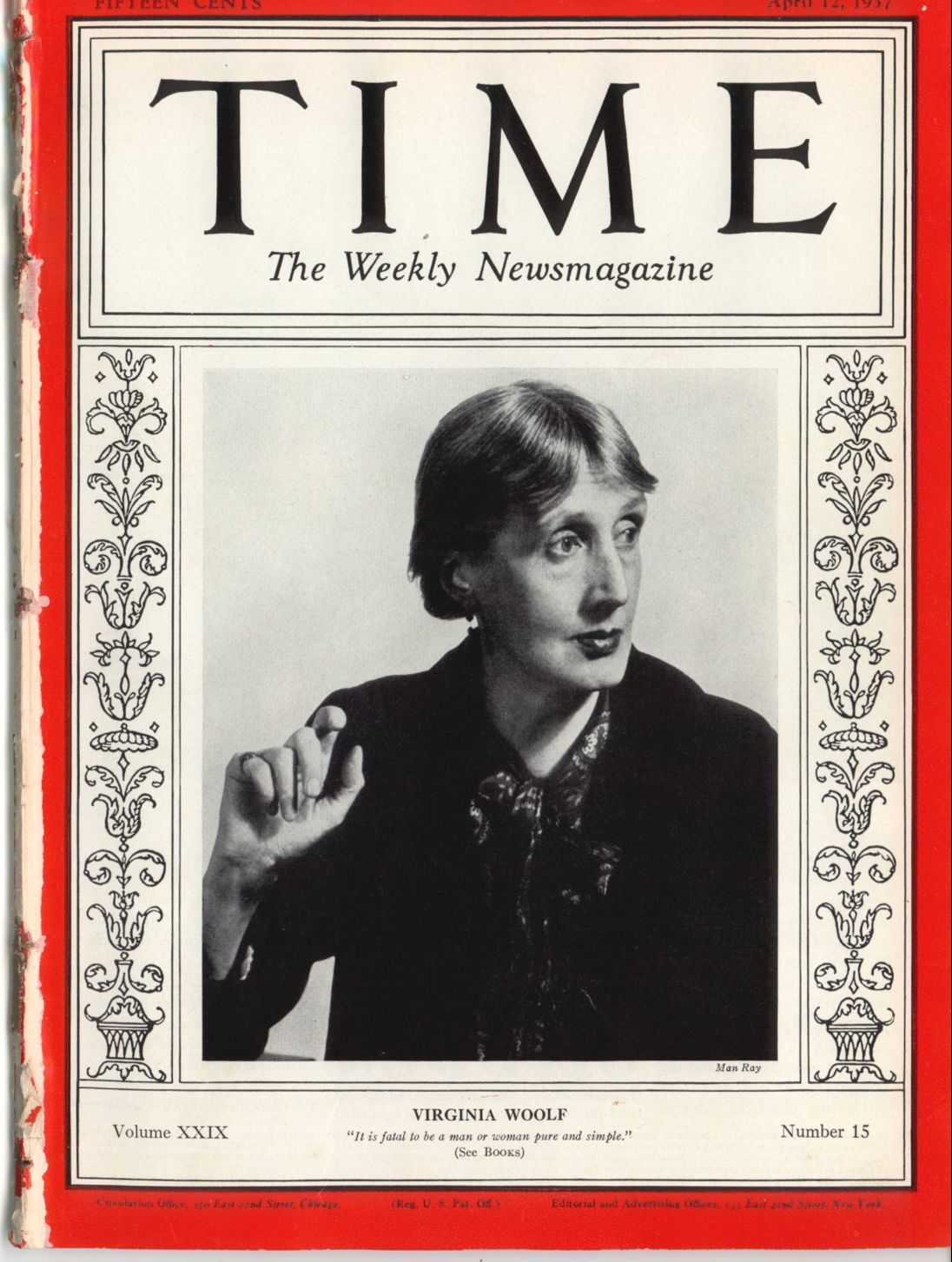

In 1929, Woolf published A Room of One's Own , a feminist essay based on lectures she had given at women's colleges, in which she examines women's role in literature. In the work, she sets forth the idea that “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Woolf pushed narrative boundaries in her next work, The Waves (1931), which she described as "a play-poem" written in the voices of six different characters. Woolf published The Years , the final novel published in her lifetime in 1937, about a family's history over the course of a generation. The following year she published Three Guineas , an essay which continued the feminist themes of A Room of One's Own and addressed fascism and war.

Throughout her career, Woolf spoke regularly at colleges and universities, penned dramatic letters, wrote moving essays and self-published a long list of short stories. By her mid-forties, she had established herself as an intellectual, an innovative and influential writer and pioneering feminist. Her ability to balance dream-like scenes with deeply tense plot lines earned her incredible respect from peers and the public alike. Despite her outward success, she continued to regularly suffer from debilitating bouts of depression and dramatic mood swings.

Suicide and Legacy

Woolf's husband, Leonard, always by her side, was quite aware of any signs that pointed to his wife’s descent into depression. He saw, as she was working on what would be her final manuscript, Between the Acts (published posthumously in 1941),that she was sinking into deepening despair. At the time, World War II was raging on and the couple decided if England was invaded by Germany, they would commit suicide together, fearing that Leonard, who was Jewish, would be in particular danger. In 1940, the couple’s London home was destroyed during the Blitz, the Germans bombing of the city.

Unable to cope with her despair, Woolf pulled on her overcoat, filled its pockets with stones and walked into the River Ouse on March 28, 1941. As she waded into the water, the stream took her with it. The authorities found her body three weeks later. Leonard Woolf had her cremated and her remains were scattered at their home, Monk's House.

Although her popularity decreased after World War II, Woolf's work resonated again with a new generation of readers during the feminist movement of the 1970s. Woolf remains one of the most influential authors of the 21st century.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Virginia Woolf

- Birth Year: 1882

- Birth date: January 25, 1882

- Birth City: Kensington, London, England

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: English author Virginia Woolf wrote modernist classics including 'Mrs. Dalloway' and 'To the Lighthouse,' as well as pioneering feminist texts, 'A Room of One's Own' and 'Three Guineas.'

- Fiction and Poetry

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Astrological Sign: Aquarius

- Death Year: 1941

- Death date: March 28, 1941

- Death City: Near Lewes, East Sussex, England

- Death Country: United Kingdom

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Virginia Woolf Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/virginia-woolf

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 12, 2022

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.

- One of the signs of passing youth is the birth of a sense of fellowship with other human beings as we take our place among them.

Famous British People

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Virginia Woolf Biography

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., English Literature, California State University - Sacramento

- B.A., English, California State University - Sacramento

(1882-1941) British writer. Virginia Woolf became one of the most prominent literary figures of the early 20th century, with novels like Mrs. Dalloway (1925), Jacob's Room (1922), To the Lighthouse (1927), and The Waves (1931).

Birth and Early Life

Virginia Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on January 25, 1882, in London. Woolf was educated at home by her father, Sir Leslie Stephen, the author of the Dictionary of English Biography , and she read extensively. Her mother, Julia Duckworth Stephen, was a nurse, who published a book on nursing. Her mother died in 1895, which was the catalyst for Virginia's first mental breakdown. Virginia's sister, Stella, died in 1897, and her father died in 1904.

Woolf learned early on that it was her fate to be "the daughter of educated men." In a journal entry shortly after her father's death in 1904, she wrote: "His life would have ended mine... No writing, no books; — inconceivable." Luckily, for the literary world, Woolf's conviction would be overcome by her itch to write.

Virginia Woolf's Writing Career

Virginia married Leonard Woolf, a journalist, in 1912. In 1917, she and her husband founded Hogarth Press, which became a successful publishing house, printing the early works of authors such as E.M Forster, Katherine Mansfield, and T.S. Eliot, and introducing the works of Sigmund Freud . Except for the first printing of Woolf's first novel, The Voyage Out (1915), Hogarth Press also published all of her works.

Together, Virginia and Leonard Woolf were a part of the famous Bloomsbury Group, which included E.M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Virginia's sister, Vanessa Bell, Gertrude Stein , James Joyce , Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot.

Virginia Woolf wrote several novels which are considered to be modern classics, including Mrs. Dalloway (1925), Jacob's Room (1922), To the Lighthouse (1927), and The Waves (1931). She also wrote A Room of One's Own (1929), which discusses the creation of literature from a feminist perspective.

Virginia Woolf's Death

From the time of her mother's death in 1895, Woolf suffered from what is now believed to have been bipolar disorder, which is characterized by alternating moods of mania and depression.

Virginia Woolf died on March 28, 1941 near Rodmell, Sussex, England. She left a note for her husband, Leonard, and for her sister, Vanessa. Then, Virginia walked to the River Ouse, put a large stone in her pocket, and drowned herself.

Virginia Woolf's Approach to Literature

Virginia Woolf's works are often closely linked to the development of feminist criticism , but she was also an important writer in the modernist movement. She revolutionized the novel with stream of consciousness , which allowed her to depict the inner lives of her characters in all too intimate detail. In A Room of One's Own Woolf writes, "we think back through our mothers if we are women. It is useless to go to the great men writers for help, however much one may go to them for pleasure."

- Virginia Woolf Quotes

"I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman." - A Room of One's Own

"One of the signs of passing youth is the birth of a sense of fellowship with other human beings as we take our place among them." - "Hours in a Library"

"Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself." - Mrs. Dalloway

"It was an uncertain spring. The weather, perpetually changing, sent clouds of blue and purple flying over the land." - The Years

"What is the meaning of life?... a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark." - To the Lighthouse

"The extraordinary irrationality of her remark, the folly of women's minds enraged him. He had ridden through the valley of death, been shattered and shivered; and now, she flew in the face of facts..." - To the Lighthouse

"Imaginative work... is like a spider's web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners.... But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in midair by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering, human beings, and are attached to the grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in." - A Room of One's Own

"When...one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Brontë who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman." - A Room of One's Own

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Quotes From 'To the Lighthouse' by Virginia Woolf

- 'Mrs. Dalloway' Review

- "Mrs. Dalloway" Quotes

- Biography of T.S. Eliot, Poet, Playwright, and Essayist

- Biography of Lucy Stone, Abolitionist and Women's Rights Reformer

- 'Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?' A Character Analysis

- Emily Dickinson's Mother, Emily Norcross

- Classic British and American Essays and Speeches

- Biography of Hilda Doolittle, Poet, Translator, and Memoirist

- Top 100 Women of History

- Examples of Epigraphs in English

- Biography of Djuna Barnes, American Artist, Journalist, and Author

- What Is the Canon in Literature?

- Biography of Nellie Bly, Investigative Journalist, World Traveler

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Virginia Woolf Was More Than Just a Women’s Writer

She was a great observer of everyday life..

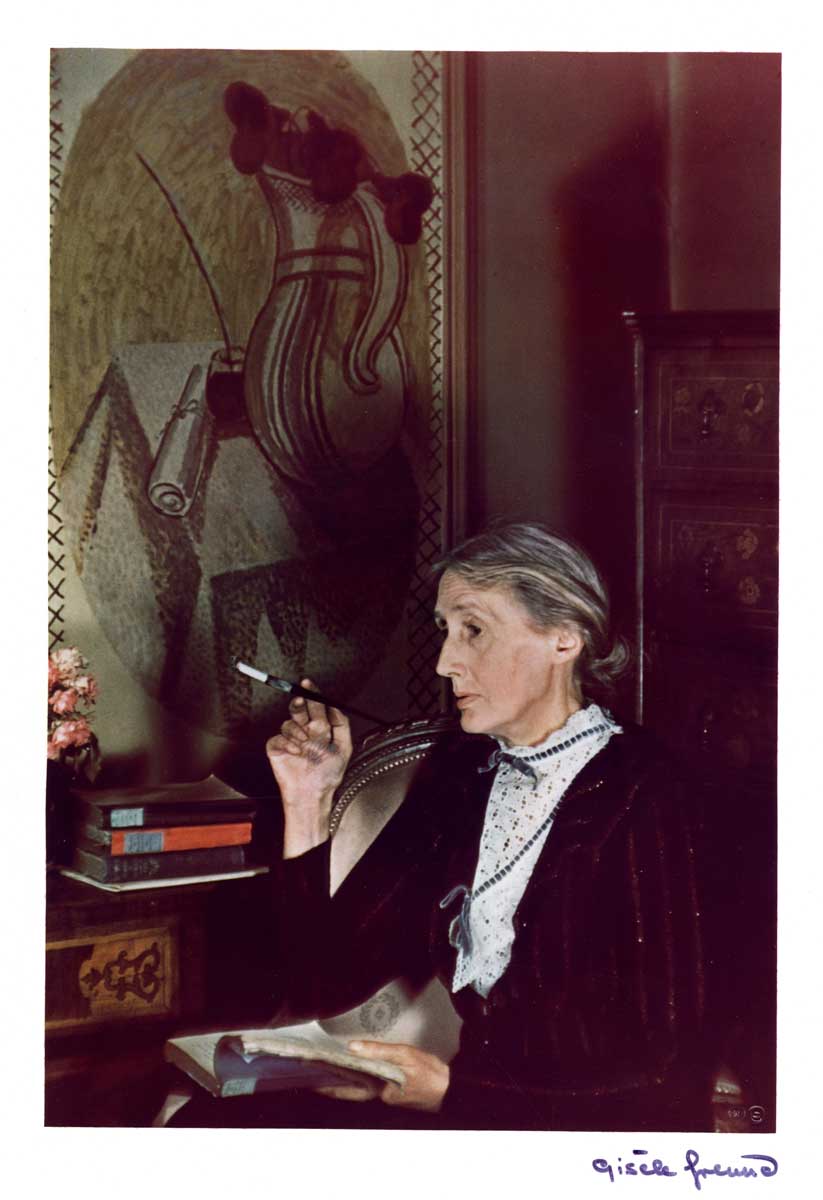

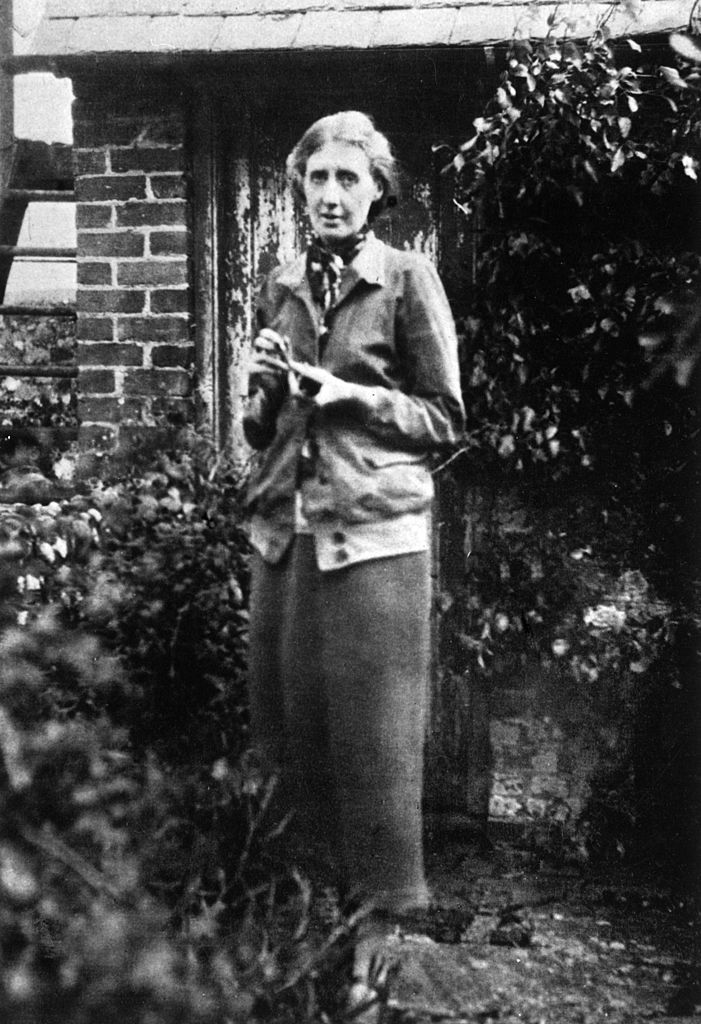

Virginia Woolf, in one of the more lively and often-seen photos of her from the 1930s.

HIP / Art Resource, NY

Virginia Woolf, that great lover of language, would surely be amused to know that, some seven decades after her death, she endures most vividly in popular culture as a pun—within the title of Edward Albee’s celebrated drama, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? In Albee’s play, a troubled college professor and his equally pained wife taunt each other by singing “Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf?,” substituting the iconic British writer’s name for that of the fairy-tale villain.

The Woolf reference seems to have no larger meaning, but, perhaps inadvertently, it gives a note of authenticity to the play’s campus setting. Woolf’s experimental novels are much discussed within academia, and her pioneering feminism has given her a special place in women’s studies programs across the country.

It’s a reputation that runs the risk of pigeonholing Woolf as a “women’s writer” and, as a frequent subject of literary theory, the author of books meant to be studied rather than enjoyed. But, in her prose, Woolf is one of the great pleasure-givers of modern literature, and her appeal transcends gender. Just ask Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours , the popular and critically acclaimed novel inspired by Woolf’s classic fictional work, Mrs. Dalloway .

“I read Mrs. Dalloway for the first time when I was a sophomore in high school,” Cunningham told readers of the Guardian newspaper in 2011. “I was a bit of a slacker, not at all the sort of kid who’d pick up a book like that on my own (it was not, I assure you, part of the curriculum at my slacker-ish school in Los Angeles). I read it in a desperate attempt to impress a girl who was reading it at the time. I hoped, for strictly amorous purposes, to appear more literate than I was.”

Cunningham didn’t really understand all of the themes of Dalloway when he first read it, and he didn’t, alas, get the girl who had inspired him to pick up Woolf’s novel. But he fell in love with Woolf’s style. “I could see, even as an untutored and rather lazy child, the density and symmetry and muscularity of Woolf’s sentences,” Cunningham recalled. “I thought, wow, she was doing with language something like what Jimi Hendrix does with a guitar. By which I meant she walked a line between chaos and order, she riffed, and just when it seemed that a sentence was veering off into randomness, she brought it back and united it with the melody.”

Woolf’s example helped drive Cunningham to become a writer himself. His novel The Hours essentially retells Dalloway as a story within a story, alternating between a variation of Woolf’s original narrative and a fictional speculation on Woolf herself. Cunningham’s 1998 novel won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, then was adapted into a 2002 film of the same name, starring Nicole Kidman as Woolf.

“I feel certain she’d have disliked the book—she was a ferocious critic,” Cunningham said of Woolf, who died in 1941. “She’d probably have had reservations about the film as well, though I like to think that it would have pleased her to see herself played by a beautiful Hollywood movie star.”

Kidman created a buzz for the movie by donning a false nose to mute her matinee-perfect face, evoking Woolf as a woman whom family friend Nigel Nicolson once described as “always beautiful but never pretty.”

Woolf, a seminal figure in feminist thought, would probably not have been surprised that a big-screen treatment of her life would spark so much talk about how she looked rather than what she did . But she was also keenly intent on grounding her literary themes within the world of sensation and physicality, so maybe there’s some value, while considering her ideas, in also remembering what it was like to see and hear her.

We know her best in profile. Many pictures of Woolf show her glancing off to the side, like the figure on a coin. The most notable exception is a 1939 photograph by Gisele Freund in which Woolf peers directly into the camera. Woolf hated the photograph—perhaps because, on some level, she knew how deftly Freund had captured her subject. “I loathe being hoisted about on top of a stick for anyone to stare at,” lamented Woolf, who complained that Freund had broken her promise not to circulate the picture.

The most striking aspect of the photo is the intensity of Woolf’s gaze. In both her conversation and her writing, Woolf had a genius for not only looking at a subject, but looking through it, teasing out inferences and implications at multiple levels. It’s perhaps why the sea figures so prominently in her fiction, as a metaphor for a world in which the bright currents we see at the surface of reality reveal, upon closer inspection, a depth that goes downward for miles.

Take, for example, Woolf’s widely anthologized essay, “The Death of the Moth,” in which she notices a moth’s last moments of life, then records the experience as a window into the fragility of all existence. “The insignificant little creature now knew death,” Woolf reports.

As I looked at the dead moth, this minute wayside triumph of so great a force over so mean an antagonist filled me with wonder. . . . The moth having righted himself now lay most decently and uncomplainingly composed. Oh yes, he seemed to say, death is stronger than I am.

Woolf takes an equally miniaturist tack in “The Mark on the Wall,” a sketch in which the narrator studies a mark on the wall ultimately revealed as a snail. Although the premise sounds militantly boring—the literary equivalent of watching paint dry—the mark on the wall works as a locus of concentration, like a hypnotist’s watch, allowing the narrator to consider everything from Shakespeare to World War I. In its subtle tracking of how the mind free-associates and its ample use of interior monolog, the sketch serves as a keynote of sorts for the modernist literary movement that Woolf worked so tirelessly to advance.

Woolf’s penetrating sensibility took some getting used to, since she expected those around her to look at the world just as unblinkingly. She didn’t seem to have much patience for small talk. Renowned scholar Hermione Lee wrote an exhaustive 1997 biography of Woolf, yet confesses some anxiety about the prospect, were it possible, of greeting Woolf in person. “I think I would have been afraid of meeting her,” Lee wrote. “I am afraid of not being intelligent enough for her.”

Nicolson, the son of Woolf’s close friend and onetime lover, Vita Sackville-West, had fond memories of hunting butterflies with Woolf when he was a boy—an outing that allowed Woolf to indulge a pastime she’d enjoyed in childhood. “Virginia could tolerate children for short periods, but fled from babies,” he recalled. Nicolson also remembered Woolf’s distaste for bland generalities, even when uttered by youngsters. She once asked the young Nicolson for a detailed report on his morning, including the quality of the sun that had awakened him, and whether he had first put on his right or left sock while dressing.

“It was a lesson in observation, but it was also a hint,” he wrote many years later. “‘Unless you catch ideas on the wing and nail them down, you will soon cease to have any.’ It was advice that I was to remember all my life.”

Thanks to a commentary Woolf did for the BBC, we don’t have to guess what she sounded like. In the 1937 recording, widely available online, Woolf reflects on how the English language pollinates and blooms into new forms. “Royal words mate with commoners,” she tells listeners in a subversive reference to the recent abdication of King Edward VIII, who had forfeited his throne to marry American Wallis Simpson. Woolf’s voice is plummy and patrician, like an English version of Eleanor Roosevelt. Not surprising, perhaps, given Woolf’s origin in one of England’s most prominent families.

She was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on January 25, 1882, the daughter of Sir Leslie Stephen, a celebrated essayist, editor, and public intellectual, and Julia Prinsep Duckworth Stephen. Julia was, according to Woolf biographer Panthea Reid, “revered for her beauty and wit, her self-sacrifice in nursing the ill, and her bravery in facing early widowhood.” Here’s how Woolf scholar Mark Hussey describes the blended household of Virginia’s childhood:

Her parents, Leslie and Julia Stephen, both previously widowed, began their marriage in 1878 with four young children: Laura (1870–1945), the daughter of Leslie Stephen and his first wife, Harriet Thackery (1840–1875); and George (1868–1934), Gerald (1870–1937), and Stella Duckworth (1869–1897), the children of Julia Prinsep (1846–1895) and Herbert Duckworth (1833–1870).

Together, Leslie and Julia had four more children: Virginia, Vanessa (1879–1961), and brothers Thoby (1880–1906) and Adrian (1883–1948). They all lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate in London.

Although Virginia’s brothers and half-brothers got university educations, Woolf was taught mostly at home—a slight that informed her thinking about how society treated women. Woolf’s family background, though, brought her within the highest circles of British cultural life.

“Woolf’s parents knew many of the intellectual luminaries of the late Victorian era well,” Hussey notes, “counting among their close friends novelists such as George Meredith, Thomas Hardy, and Henry James. Woolf’s great-aunt Julia Margaret Cameron was a pioneering photographer who made portraits of the poets Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning, of the naturalist Charles Darwin, and of the philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle, among many others.”

Woolf also had free range over her father’s mammoth library and made the most of it. Reading was her passion—and an act, like any passion, to be engaged actively, not sampled passively. In an essay about her father, Woolf recalled his habit of reciting poetry as he walked or climbed the stairs, and the lesson she took from it seems inescapable. Early on, she learned to pair literature with vitality and movement, and that sensibility runs throughout her lively critical essays, gathered in numerous volumes, including her seminal 1925 collection, The Common Reader . The title takes its cue from Woolf’s appeal to the kind of reader who, like her, was essentially self-educated rather than a professional scholar.

In a 1931 essay, “The Love of Reading,” Woolf describes what it’s like to encounter a literary masterpiece:

The great writers thus often require us to make heroic efforts in order to read them rightly. They bend us and break us. To go from Defoe to Jane Austen, from Hardy to Peacock, from Trollope to Meredith, from Richardson to Rudyard Kipling is to be wrenched and distorted, to be thrown violently this way and that.

As Woolf saw it, reading was a mythic act, not simply a cozy fireside pastime. John Sparrow, reviewing Woolf’s work in the Spectator , connected her view of reading with her broader literary life: “She writes vividly because she reads vividly.”

The Stephen family’s summers in coastal Cornwall also shaped Woolf indelibly, exposing her to the ocean as a source of literary inspiration—and creating memories she would fictionalize for her acclaimed novel, To the Lighthouse .

Darker experiences shadowed Woolf’s youth. In writings not widely known until after her death, she described being sexually abused by her older stepbrothers, George and Gerald Duckworth. Scholars have often discussed how this trauma might have complicated her mental health, which challenged her through much of her life. She had periodic nervous breakdowns, and depression ultimately claimed her life.

“Virginia was a manic-depressive, but at that time the illness had not yet been identified and so could not be treated,” notes biographer Reid. “For her, a normal mood of excitement or depression would become inexplicably magnified so that she could no longer find her sane, balanced self.”

The writing desk became her refuge. “The only way I keep afloat is by working,” Woolf confessed. “Directly I stop working I feel that I am sinking down, down.”

Woolf’s mother died in 1895, and her father died in 1904. After her father’s death, Virginia and the other Stephen siblings, now grown, moved to London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood. “It was a district of London,” noted Nicolson, “that in spite of the elegance of its Georgian squares was considered . . . to be faintly decadent, the resort of raffish divorcées and indolent students, loose in its morals and behavior.”

Bloomsbury’s bohemian sensibility suited Woolf, who joined with other intellectuals in her newfound community to form the Bloomsbury Group, an informal social circle that included Woolf’s sister Vanessa, an artist; Vanessa’s husband, the art critic Clive Bell; artist Roger Fry; economist John Maynard Keynes; and writers Lytton Strachey and E. M. Forster. Through Bloomsbury, Virginia also met writer Leonard Woolf, and they married in 1912.

The Bloomsbury Group had no clear philosophy, although its members shared an enthusiasm for leftish politics and a general willingness to experiment with new kinds of visual and literary art.

The Voyage Out , Woolf’s debut novel published in 1915, follows a fairly conventional form, but its plot—a female protagonist exploring her inner life through an epic voyage—suggested that what women saw and felt and heard and experienced was worthy of fiction, independent of their connection to men. In a series of lectures published in 1929 as A Room of One’s Own , Woolf pointed to the special challenges that women faced in finding the basic necessities for writing—a small income and a quiet place to think. A Room of One’s Own is a formative feminist document, but critic Robert Kanigel argues that men are cheating themselves if they don’t embrace the book, too. “Woolf’s is not a Spartan, clippity-clop style such as the one Ernest Hemingway was perfecting in Paris at about the same time,” Kanigel observes. “This is leisurely, ruminative, with long paragraphs that march up and down the page, long trains of thought, and rich digressions almost hypnotic in their effect. And once trapped within the sweet, sticky filament of her web of words, one is left with no wish whatever to be set free.”

During the Woolfs’ marriage, Virginia had flirtations with women and an affair with Sackville-West, a fellow author in her social circle. Even so, Leonard and Virginia remained close, buying a small printing press and starting a publishing house, Hogarth Press, in 1917. Leonard thought it might be a soothing diversion for Virginia—perhaps the first and only case of anyone entering book publishing to advance their sanity.

If Virginia Woolf had never published a single word of her own, her role in Hogarth would have secured her a place in literary history. Thanks to the Woolfs’ tiny press, the world got its first look at the early work of Katherine Mansfield, T. S. Eliot, and Forster. The press also published Virginia’s work, of course, including novels of increasingly daring scope. In To the Lighthouse , a family summers along the coast, the lighthouse on the horizon suggesting an assuringly fixed universe. But, as the novel unfolds over a decade, we see the subtle working of time and how it shapes the perceptions of various characters.

A young Eudora Welty picked up To the Lighthouse and found her own world changed. “Blessed with luck and innocence, I fell upon the novel that once and forever opened the door of imaginative fiction for me, and read it cold, in all its wonder and magnitude,” Welty recalled.

The Woolfs divided their time between London, a city that Virginia loved and often wrote about, and Monk’s House, a modest country home in Sussex the couple was able to buy as Virginia’s career bloomed. Even as she welcomed literary experiment, Woolf grew wistful about the future of the traditional letter, which she saw being eclipsed by the speed of news-gathering and the telephone. Almost as if to disprove her own point, Woolf wrote as many as six letters a day.

“Virginia Woolf was a compulsive letter writer,” said English critic V. S. Pritchett. “She did not much care for the solitude she needed but lived for news, gossip, and the expectancy of talk.”

Her letters, published in several volumes, shimmer with brilliant detail. In a letter written during World War II, for example, Woolf interrupts her message to Benedict Nicolson to go outside and watch the German bombers flying over her house. “The raiders began emitting long trails of smoke,” she reports. “I wondered if a bomb was going to fall on top of me. . . . Then I dipped into your letter again.”

The war proved too much for her. Distraught by its destruction, sensing another nervous breakdown, and worried about the burden it would impose on Leonard, Virginia stuffed her pockets with stones and drowned herself in the River Ouse near Monk’s House on March 28, 1941.

But Cunningham says it would be a mistake to define Woolf by her death. “She did, of course, have her darker interludes,” he concedes. “But when not sunk in her periodic depressions, [she] was the person one most hoped would come to the party; the one who could speak amusingly on just about any subject; the one who glittered and charmed; who was interested in what other people had to say (though not, I admit, always encouraging about their opinions); who loved the idea of the future and all the wonders it might bring.”

Her influence on subsequent generations of writers has been deep. You can see flashes of her vivid sensitivity in the work of Annie Dillard, a bit of her wry critical eye in the recent essays of Rebecca Solnit. Novelist and essayist Daphne Merkin says that despite her edges, Woolf should be remembered as “luminous and tender and generous, the person you would most like to see coming down the path.” Woolf’s legacy marks Merkin’s work, too, although there’s never been anyone else quite like Virginia Woolf.

“The world of the arts was her native territory; she ranged freely under her own sky, speaking her mother tongue fearlessly,” novelist Katherine Anne Porter said of Woolf. “She was at home in that place as much as anyone ever was.”

Danny Heitman is the editor of Phi Kappa Phi’s Forum magazine and a columnist for the Advocate newspaper in Louisiana. He writes frequently about arts and culture for national publications, including the Wall Street Journal and the Christian Science Monitor.

Funding information

NEH has funded numerous projects related to Virginia Woolf, including four separate r esearch fellowships since 1995 and three education seminars for schoolteachers on Woolf’s major novels. In 2010, Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois, received $175,000 to support WoolfOnline , which documents the biographical, textual, and publication history of To the Lighthouse.

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

Biography Online

Virginia Woolf Biography

She was born in London, in 1882. Her father, Sir Leslie Stephen, was a notable historian, author and editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. Her mother Julia Stephen was also well connected in cultural circles and acted as a model for the Pre-Raphaelite artists and photographers.

Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell

Virginia was educated at her Kensington home by her parents with her step-brothers and stepsisters. She was quite a delicate child – ill-suited to the rough and tumble of ordinary schools. She grew up in a literary environment, she devoured many books from her father’s library. In particular, she gained a love of the Elizabethan period and read from Hakluyt’s Voyages from an early age. Living in such a literary environment she came into contact with some of the leading intellects of the day, including Thomas Hardy, John Ruskin, and Edmund Gosse.

She later took lessons at the Ladies’ Department of Kings College, London. Her brothers went to Cambridge, and although Virginia resented not being able to study at Cambridge, through her brothers, she later became involved in the circle of Cambridge graduates.

When Virginia was 13, the death of her mother left a profound mark on her, and she had a nervous breakdown. This nervous breakdown was the beginning of a lifetime of mood swings – manic depression and she frequently sought treatment for her mental instability but struggled to find any cure.

These mood swings made social life more difficult, but she still became friendly with some of the leading literary and cultural figures of the day, including Rupert Brooke, John Maynard Keynes , Clive Bell and Saxon Sydney-Turner. These group of literary figures became known as the Bloomsbury Group.

During this time she had an active correspondence with suffragettes such as Mrs Fawcett , Emily Pankhurst and others. Although she never took part in the activities of the suffragettes she wrote her clear support for the aims of female emancipation. This was made particularly clear in an essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’ (1929) where Woolf highlights the difference between how woman are treated by patriarchal society and the idealised view of women in fiction.

“She dominates the lives of kings and conquerors in fiction; in fact she was the slave of any boy whose parents forced a ring upon her finger. Some of the most inspired words and profound thoughts in literature fall from her lips; in real life she could hardly read; scarcely spell; and was the property of her husband.” ‘A Room of One’s Own’ (1929)

She is considered an important feminist writer and argued for the importance of women’s education.

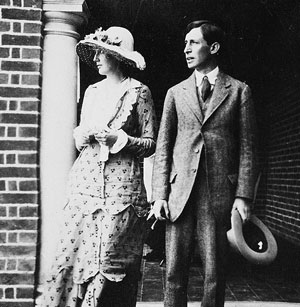

Virginia and Leonard Woolf, 1912

In 1912, Virginia married writer and critic Leonard Woolf, and though he was poor, the marriage was happy. Leonard was Jewish, and she was rather proud of his Jewishness – even though she has been accused of some anti-Semitism in her works – often depicting Jews in a stereotypical way. The couple were both appalled by the rise of fascism in the 1930s, and they were both on Hitler’s list of undesirable cultural figures.

Style of writing

She began working as a journalist, writing articles for the Times Literary Supplement in the early 1900s. In 1915, at the age of 33, she published her first novel. – The Voyage Out . It was a revised version of a novel she began writing several years ago. In 1917, Virginia and Leonard founded the Hogarth Press which published her novels and later works by other writers, such as T.S.Eliot, E.M. Forster and Lauren van der Post.

She was considered a modernist author, for her experimentation in a stream of consciousness writing, reminiscent of the period. Often her novels were based on quite ordinary, even banal situations. But, she sought to explore the underlying psychological and emotional motives of the characters involved. In particular, she used her great powers of observation to examine how perceptions can radically change through time She also explored ideas of sexual ambivalence (she herself had a brief lesbian affair with Vita Sackville-West,) shell shock from First World War, and the rapid changes of society.

Her three most important novels were Mrs. Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) and The Waves (1931)

During the Second World War, she became increasingly depressed, due to a combination of the blitz and the return of her mental demons. Fearing she was going mad again, she took her own life, filling her pockets with stones and jumping into the River Ouse.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Virginia Wolf” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net Published 3 Feb. 2013. Last updated 18 March 2020.

Virginia Woolf – A Room of One’s Own

Virginia Woolf – A Room of One’s Own at Amazon

Virginia Woolf Quotes

A Room of One’s Own (1929)

The beauty of the world which is so soon to perish, has two edges, one of laughter, one of anguish, cutting the heart asunder. Ch. 1 (p. 17) Have you any notion how many books are written about women in the course of one year? Have you any notion how many are written by men? Are you aware that you are, perhaps, the most discussed animal in the universe? Ch. 2 (p. 26) Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size. Ch. 2 (p. 35) I would venture to guess than Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman. Ch. 3 (p. 51) Very often misquoted as “For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.” For it needs little skill in psychology to be sure that a highly gifted girl who had tried to use her gift for poetry would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity to a certainty. Ch. 3 (p. 51) Literature is strewn with the wreckage of men who have minded beyond reason the opinions of others. Ch. 3 (p. 58) The history of men’s opposition to women’s emancipation is more interesting perhaps than the story of that emancipation itself. Ch. 3 (p. 72) Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind. Ch. 4 (p. 90)

The Waves (1931)

But look – he flicks his hand to the back of his neck. For such gesture one falls hopelessly in love for a lifetime. p. 30

Here on this ring of grass we have sat together, bound by the tremendous power of some inner compulsion. The trees wave, the clouds pass. The time approaches when these soliloquies shall be shared. We shall not always give out a sound like a beaten gong as one sensation strikes and then another. Children, our lives have been gongs striking; clamour and boasting; cries of despair; blows on the nape of the neck in gardens. pp. 39-40

The Death of the Moth and Other Essays (1942)

Once you begin to take yourself seriously as a leader or as a follower, as a modern or as a conservative, then you become a self-conscious, biting, and scratching little animal whose work is not of the slightest value or importance to anybody.

The Moment and Other Essays (1948)

‘If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.

Granite and Rainbow (1958)

The extraordinary woman depends on the ordinary woman. It is only when we know what were the conditions of the average woman’s life … it is only when we can measure the way of life and the experience of life made possible to the ordinary woman that we can account for the success or failure of the extraordinary woman as a writer. “Women and Fiction”

Related pages

Suggestions

- An Inspector Calls

- Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

- Of Mice and Men

- The Catcher in the Rye

Please wait while we process your payment

Reset Password

Your password reset email should arrive shortly..

If you don't see it, please check your spam folder. Sometimes it can end up there.

Something went wrong

Log in or create account.

- Be between 8-15 characters.

- Contain at least one capital letter.

- Contain at least one number.

- Be different from your email address.

By signing up you agree to our terms and privacy policy .

Don’t have an account? Subscribe now

Create Your Account

Sign up for your FREE 7-day trial

- Ad-free experience

- Note-taking

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AP® English Test Prep

- Plus much more

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Already have an account? Log in

Choose Your Plan

Group Discount

$4.99 /month + tax

$24.99 /year + tax

Save over 50% with a SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan!

Purchasing SparkNotes PLUS for a group?

Get Annual Plans at a discount when you buy 2 or more!

$24.99 $18.74 / subscription + tax

Subtotal $37.48 + tax

Save 25% on 2-49 accounts

Save 30% on 50-99 accounts

Want 100 or more? Contact us for a customized plan.

Payment Details

Payment Summary

SparkNotes Plus

Change

You'll be billed after your free trial ends.

7-Day Free Trial

Not Applicable

Renews April 29, 2024 April 22, 2024

Discounts (applied to next billing)

SNPLUSROCKS20 | 20% Discount

This is not a valid promo code.

Discount Code (one code per order)

SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan - Group Discount

SparkNotes Plus subscription is $4.99/month or $24.99/year as selected above. The free trial period is the first 7 days of your subscription. TO CANCEL YOUR SUBSCRIPTION AND AVOID BEING CHARGED, YOU MUST CANCEL BEFORE THE END OF THE FREE TRIAL PERIOD. You may cancel your subscription on your Subscription and Billing page or contact Customer Support at [email protected] . Your subscription will continue automatically once the free trial period is over. Free trial is available to new customers only.

For the next 7 days, you'll have access to awesome PLUS stuff like AP English test prep, No Fear Shakespeare translations and audio, a note-taking tool, personalized dashboard, & much more!

You’ve successfully purchased a group discount. Your group members can use the joining link below to redeem their group membership. You'll also receive an email with the link.

Members will be prompted to log in or create an account to redeem their group membership.

Thanks for creating a SparkNotes account! Continue to start your free trial.

We're sorry, we could not create your account. SparkNotes PLUS is not available in your country. See what countries we’re in.

There was an error creating your account. Please check your payment details and try again.

Your PLUS subscription has expired

- We’d love to have you back! Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Go ad-free AND get instant access to grade-boosting study tools!

- Start the school year strong with SparkNotes PLUS!

- Start the school year strong with PLUS!

Virginia Woolf

Virginia woolf biography.

In 1882, Virginia Woolf was born into a world that was quickly evolving. Her family was split by the mores of the stifling Victorian era, with her half-siblings firmly on the side of "polite society" and her own brothers and sisters curious about what lie on the darker side of that society. Woolf's father, the eminent scholar and biographer Sir Leslie Stephen, was a man of letters and a man of vision, befriending and encouraging authors who were then unknown, including Henry James and Thomas Hardy. As much as he encouraged his own daughters to better their minds, higher education, even in the Stephen household, was reserved for the men of the family-Woolf's brothers Thoby and Adrian. This was a bitter lesson in inequality that Woolf could never forget, even when she was later offered honorary degrees from Cambridge and other British universities that, when she was growing up, didn't even admit women into their ranks.

When Woolf and her sister Vanessa moved out of their posh London neighborhood and into a slightly seedy neighborhood called Bloomsbury with their brothers, they were on the cusp of something entirely new. They could either fall backwards into the safe arms of the upper-middle class society in which they grew up, or they could push forth into the somewhat avant-garde, ultra-intellectual and suspect world of Thoby's Cambridge friends-Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Desmond MacCarthy, among others. The sisters plunged headfirst into the Bloomsbury Group.

The Bloomsbury Group started out as a weekly gathering of old college friends. However, as time passed, it became an intense salon of ideas, philosophy, and theories on art and politics. Woolf and Vanessa were both important members of the group. For the first time, Woolf was around people who didn't seem to care that she was a woman, and who expected her to contribute to the group both in conversation and in deed (as in her novels). Though her old friends were scandalized by the company she was keeping (the Bloomsbury Group was famous, even in its own time, and its members were considered rude, unkempt and depraved), Woolf felt at ease among her new friends, and flourished in their company.

With this encouragement, she began writing. First she began publishing short journalistic pieces, and then longer reviews. Before long she was a regular contributor to a number of London weeklies, and was privately trying her hand at fiction. After her first novel, The Voyage Out was published to good reviews, Woolf never looked back and began producing novel after successful and daring novel. Through her often difficult but nearly always brilliant novels, she became one of the most important Modernist writers, along with James Joyce and T.S. Eliot.

Modernism was a literary movement in which its practitioners discovered new ways to relate the human experience in an uncertain, somewhat hopeless time in history. World War One had just demoralized England and the Continent, and a whole generation of young men and women were, as Gertrude Stein would later put it, "lost." Changing times demanded different modes of expression. Woolf and James Joyce, for example, utilized stream-of-consciousness to convey a character's interior monologue and to capture the irregularities and meanderings of thought.

Despite her successes, Woolf battled mental illness for most of her life. Mental illness was still poorly understood in the first half of the Twentieth Century, and Woolf–who was likely suffering from manic-depression–had few tools at her disposal with which to battle her inner demons. She lost weeks of precious work time due to her bouts with mania or with depression, and she was plagued, during these times of madness, by voices in her head. However, her devoted husband Leonard shepherded her through these difficult periods in her life and she seemed to bounce back and produce another great work of literature.

However, on March 28, 1941, as World War II raged on, Woolf left her husband two suicide notes, walked to the River Ouse, filled her pockets with heavy stones, and drowned herself. With her death, the world lost one of its most gifted voices. She left a canon of experimental, stunning fiction and a collection of insightful and incisive nonfiction and criticism. Her belief that women writers face two hindrances-social inferiority and economic dependence-was a revolutionary stance to take in the twenties when A Room of One's Own was published. Even more so was her assertion that all women deserved equal opportunity in education and career. Despite having had no educational opportunity herself, Virginia Woolf became, through her own efforts, one of the best writers of the twentieth century.

Virginia Woolf Study Guides

Mrs. dalloway, a room of one's own, to the lighthouse, “kew gardens”, “a haunted house”, virginia woolf quotes.

The strange thing about life is that though the nature of it must have been apparent to every one for hundreds of years, no one has left any adequate account of it.

Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end.

A light here required a shadow there.

There were the eternal problems: suffering; death; the poor.

What is the meaning of life? That was all — a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark.

A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.

The beauty of the world which is so soon to perish, has two edges, one of laughter, one of anguish, cutting the heart asunder.

If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.

The extraordinary woman depends on the ordinary woman.

Fiction is like a spider's web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners.

Virginia Woolf Novels

The voyage out, night and day, jacob's room, mrs dalloway, between the acts, virginia woolf short stories, kew gardens (short story), monday or tuesday, a haunted house and other short stories, mrs dalloway's party, the complete shorter fiction, carlyle's house and other sketches, take a study break.

Every Literary Reference Found in Taylor Swift's Lyrics

The 7 Most Messed-Up Short Stories We All Had to Read in School

QUIZ: Which Greek God Are You?

Answer These 7 Questions and We'll Tell You How You'll Do on Your AP Exams

- Corrections

Virginia Woolf: A Literary Icon of Modernism

Virginia Woolf was a literary pioneer and arguably the greatest English writer of the modernist period.

Virginia Woolf is one of the great prose stylists of English literature and has become something of a literary icon. A society beauty in her youth, a prodigiously talented author, and a pioneer of the feminist movement, Virginia Woolf’s legacy is perhaps somewhat overshadowed by the bouts of mental illness she suffered throughout her life and her suicide in 1941. Though she struggled with depression at various points in her adult life, she also produced a remarkable body of work, ranging from fiction to non-fiction, and is rightly celebrated as not only one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century but of all time.

Virginia Woolf: The Early Years

Named after an unfortunate aunt on her mother’s side of the family, Adeline Virginia Stephen was born on January 25, 1882 to Julia Duckworth Stephen and Sir Leslie Stephen, founding editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. Both her parents had already been married previously. While her disabled half-sister, Laura, from her father’s first marriage would be institutionalized by the time Virginia was nine years old, her half-sister and half-brothers on her mother’s side (George, Stella, and Gerald) lived with the four Stephen children at 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington, London.

In many ways, her childhood was fairly standard for a young girl of her social class. She was educated at home by her parents while her brothers went off to school and university – a gender disparity which she came to resent. While he did not send his daughters to school, Leslie Stephen did allow all his children “free run of a large and quite unexpurgated library,” from which the young Virginia read voraciously (see Further Reading, Woolf, ‘Leslie Stephen’, p. 114). Recognizing her literary talents, her father cherished the hope that Virginia – rather than his two sons, Thoby and Adrian – would follow in his footsteps and become a writer.

Her childhood was also marred by tragedy, however. Her mother died in 1895, after falling ill with influenza. That summer, Virginia – aged just 13 – suffered her first mental breakdown. In addition, from the age of six, she was sexually assaulted by her half-brothers, George and Gerald Duckworth, throughout her childhood. Her sister, Vanessa, was also assaulted, and Hermione Lee suggests that her half-sister Laura most probably was, too. When their father became ill in 1902, Virginia and Vanessa were still more vulnerable and exposed to their half-brothers, and his death in 1904 led Virginia to suffer another mental breakdown.

Finding Freedom in Bloomsbury

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Though the death of her father deeply affected Virginia, it also freed her from the conventions imposed on women in middle-class society. No longer having to play hostess to Sir Leslie’s teatime guests, Virginia and her siblings (at Vanessa’s instigation) moved out of their childhood home in Kensington and into 46 Gordon Square in Bloomsbury. At the time, Bloomsbury was not seen as a desirable locale. This, however, was part of the attraction for the Stephen siblings, who were keen to cast off the strictures and limitations of their middle-class Victorian upbringing in bohemian Bloomsbury.

Here, Virginia began teaching evening classes at Morley College. And, along with her siblings, she held “at homes” for Thoby’s friends at Cambridge University, including Lytton Strachey, Saxon Sydney Turner, Clive Bell, and Leonard Woolf. This marked the beginning of what came to be known as the Bloomsbury Group. When her favorite brother, Thoby, contracted typhoid during a family holiday to Greece and died shortly after returning to London at their Bloomsbury home in 1906, the Bloomsbury Group could have fallen apart. Shortly after his death, however, Vanessa agreed to marry Clive Bell. And when Virginia married Leonard Woolf in 1912, the group was even further consolidated, with the two Stephen sisters centering the group as Thoby had done before them.

The First Three Novels: The Voyage Out, Night and Day, & Jacob’s Room

When Virginia Stephen married Leonard Woolf in 1912, she was thirty years old and, though she thought of herself as a writer, had yet to publish a novel. She was, however, working on what would be her first novel, The Voyage Out (1915). This, along with her next novel, Night and Day (1919), was published by Duckworth Press, established by her half-brother, Gerald. Not only did Virginia not want to be dependent on her abusive half-brother when publishing her books, she felt the pressure to write books that would be sufficiently popular to secure her further publishing deals for any future novels and thus secure her future career as a writer. Determined to revolutionize the novel, this state of affairs did not suit Virginia Woolf or her creative ambitions.

In 1915, however, Leonard and Virginia Woolf moved to Hogarth House on Paradise Road, also in London. It was here that the couple would set up the Hogarth Press, which not only went on to print all of Virginia’s later works but also work by T. S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, and the first English translations of the works of Sigmund Freud .

Though it did entail more work for the young couple, having their own printing press gave Virginia Woolf the freedom to write whatever she liked. Her third novel, Jacob’s Room , was published by the Hogarth Press in 1922 and it marks a significant turn in her writing style. Embracing a more experimental mode of writing with Jacob’s Room, Woolf found her voice as a writer and paved the way for her later works.

Continued Success: Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, & Orlando

The first novel published after Jacob’s Room was Mrs Dalloway (1925), which is widely considered to be among Woolf’s greatest works. While Katherine Mansfield had criticized Woolf for neglecting to mention the First World War in her earlier novel Night and Day , here, Woolf drew on her own experiences of illness to depict the inner lives of Clarissa Dalloway and Septimus Warren Smith, a shell-shocked veteran struggling to cope with civilian life.

For her next novel, Woolf drew on her childhood holidays in St. Ives and attempted to exorcise the ghosts of her late parents. In To the Lighthouse (1927), Woolf depicts the lives (and deaths) of members of the Ramsay family both before and after the First World War and a series of deaths that devastate the family. In doing so, she focuses on the human cost of war and loss while meditating upon the struggles faced by female artists .

While writing To the Lighthouse , Virginia Woolf had fallen in love with the English aristocratic socialite and writer Vita Sackville-West. As both a break from her own more serious works of literary experimentation and a love letter to Vita, she published Orlando just one year after the release of To the Lighthouse . In Orlando , Virginia Woolf draws on and fictionalizes Vita’s aristocratic ancestry to create the novel’s eponymous protagonist, who lives for centuries and transitions from a man to a woman. Not only did Virginia Woolf give Vita a fictionalized version of her beloved childhood home, Knole, to keep, she also wrote a feminist classic and an important text for the field of transgender studies .

Politics and Polemic

As well as writing some of the twentieth century’s most important novels, Virginia Woolf was also a celebrated essayist and writer of non-fiction. Her essays were collected into two volumes of The Common Reader, and she was involved in the UK’s Labour Party through her husband.

Perhaps her most famous work of non-fiction, however, is A Room of One’s Own , which is now considered a foundational feminist text. While the main body of the text focuses on women’s issues, towards the end of A Room of One’s Own, she takes aim at Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy. And it was the rise of fascism that was to inspire her subsequent extended work of polemical non-fiction, Three Guineas . As a lifelong pacifist, she was horrified by fascist Italy and Germany , having visited both countries before the outbreak of the Second World War with Leonard. In Three Guineas , she seeks to draw parallels between fascism and anti-feminism in these regimes. Despite the seriousness of the topics she covered, both A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas maintain a lightness of tone and an impish irreverence for institutions and figures of authority.

Late Style: The Waves, The Years, & Between the Acts

The Waves was published in 1931 and is perhaps Woolf’s most formally audacious and experimental novel. The novel’s narration is split between six characters, whom we follow from childhood to adulthood, and the events of the novel are focalized and filtered through their various and often interweaving consciousnesses. Throughout her work, Woolf was concerned with exploring human interiority, though nowhere does she explore it so thoroughly as in The Waves .

The Years (1937), then, might seem to be something of a contrast. Originally conceived of as a hybrid of the essay and the novel, extricated the two halves, which came to be The Years and Three Guineas . However, shorn of its experimental hybridity, The Years may not initially seem to be a very experimental novel at all, but rather a return to the realist family sagas of the previous century. Here, however, Woolf sought to demonstrate how the wider currents of public and political life intersect with the privacy of her characters’ lives. Perhaps due to its outward conventionality, The Years was Woolf’s best-selling novel within her own lifetime.

Virginia Woolf would not live to see her final novel, Between the Acts (1941), published. Focusing on the lead-up to and performance of a pageant play as part of a festival in a small village in southern England shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, Between the Acts captures a moment of calm before the storm. Virginia Woolf, however, did not live to see the end of the war.

Disappointed by the reception of her biography of Roger Fry and feeling unmoored and uncertain following the destruction of her London homes during the Blitz, she fell into a depression and suffered what was to be her final breakdown. On 28 March 1941, she weighed her pockets down with stones and waded into the River Ouse, where she drowned. She was 59 years old.

Virginia Woolf’s life was thus cut tragically short. Yet, in spite of her mental health struggles, she managed to produce a prodigious output of writing – and, more importantly, she did so on her own terms, according to her own artistic ambitions. A lifelong advocate for pacifism and feminism and a scathing critic of the rise of fascism in the early twentieth century, she was as fearless when it came to speaking her mind in her non-fictional works as she was when charting new artistic territories in her fiction. And it is for these achievements that Woolf deserves to be remembered and for which she has become a literary icon.

Further Reading:

Lee, Hermione, Virginia Woolf (London: Vintage, 1997).

Nadel, Ira, Virginia Woolf (London: Reaktion Books, 2016).

Spalding, Frances, The Bloomsbury Group (London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2021).

Woolf, Virginia, ‘Leslie Stephen’, in Selected Essays , ed. by David Bradshaw (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 111-15.

Woolf, Virginia, Moments of Being: Autobiographical Writings , ed. by Jeanne Schulkind (London: Pimlico, 2002).

Artist’s Homes: Creative Spaces and Art Studios of Famous Painters

By Catherine Dent MA 20th and 21st Century Literary Studies, BA English Literature Catherine holds a first-class BA from Durham University and an MA with distinction, also from Durham, where she specialized in the representation of glass objects in the work of Virginia Woolf. In her spare time, she enjoys writing fiction, reading, and spending time with her rescue dog, Finn.

Frequently Read Together

9 Times Virginia Woolf Made a Lasting Impact on Art

The Impact of Sigmund Freud’s Theories on Art

6 Great Female Artists Who Had Long Been Unknown

Virginia Woolf

By ellen gutoskey | dec 16, 2019.

AUTHORS (1882–1941); LONDON, ENGLAND

Best known for her highly imaginative and nonlinear novels like Mrs. Dalloway , Orlando , and To the Lighthouse —and also perhaps because her name was borrowed for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Edward Albee's Tony Award-winning play (which was also nominated for a Pulitzer Prize)—writer Virginia Woolf lived her life as unabashedly as many of the characters in her novels. Find out what books she wrote, what quotes she said, and how she ultimately succumbed to a lifelong battle with mental illness.

1. Virginia Woolf's books rarely stuck to the status quo.

Author Virginia Woolf was born in London in 1882 and helped pioneer modern literature and feminist theory by refusing to adhere to the status quo on just about anything. Not only does she break the normal linear narrative structure in novels like Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse , but she also often presents complex characters who struggle to escape the confines of certain societal expectations of them—especially women.

2. Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves is a prime example of her unconventional style of writing.

Though technically a novel, Virginia Woolf called The Waves a “play-poem”—and for good reason. It’s told from the perspectives of six different characters, but it doesn’t switch perspectives between chapters or otherwise relatively long segments. Instead, each character narrates their version of whatever’s happening (and their reaction to whatever’s happening) in quick succession, resulting in a piecemeal portrait of a very ambiguous plot. Their narration is punctuated with lyrical descriptions of the sea and sky, making it seem like a play at times, and a poem at others.

3. Virginia Woolf’s book Orlando: A Biography is based on her lover, Vita Sackville-West.

Orlando , a sweeping story that spans more than 400 years in the life of the slowly aging protagonist, is actually a novel, not a biography—though it is heavily inspired by Woolf’s female lover, the writer Vita Sackville-West, who sometimes dressed as a man and went by the name “Julian.”

“A biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day, called Orlando . Vita; only with a change about from one sex to the other,” Woolf wrote of the book in her diary. In the book, the main character, Orlando, begins the story as a man and ends it as a woman.

4. Virginia Woolf’s essay "A Room of One’s Own" imagines the life of a fictional sister of William Shakespeare.

At one point in "A Room of One’s Own," an extended essay based on two lectures Woolf gave at university literary societies in 1928, the author creates a character named Judith Shakespeare, who was “as adventurous, as imaginative, as agog to see the world” as her brother, William. However, while William gets to further his education and live up to his potential, Judith must stay at home and eventually marry for convenience. Interestingly enough, William Shakespeare did have a sister who lived into adulthood, but her name was Joan.

5. Virginia Woolf’s death by suicide was the result of a lifelong battle with mental illness.

In 1941, at 59 years old, Woolf filled her pockets with rocks and drowned herself in a river. She had lived through sexual abuse, both her parents’ premature deaths, nervous breakdowns, manic depression, hallucinations, and several suicide attempts.

“I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times,” Woolf wrote in a heartbreaking suicide note to her husband, Leonard. “You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer.”

6. The author of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? got the inspiration for its title from graffiti in a bar bathroom.

In the early 1950s, playwright Edward Albee saw the question "Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" written in soap on the bathroom mirror of a Greenwich Village bar. Later, while writing the now-famous play , he recalled the phrase, thinking it a fitting pun on the song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” from Disney’s 1933 film The Three Little Pigs . In a 1966 interview with The Paris Review , Albee explained that it was meant as a “typical university, intellectual joke” about being afraid of “living life without false illusions.” In other words, it’s not actually about being afraid of Virginia Woolf herself, but of the authentic, unabashed life she championed in her life and works.

Famous Virginia Woolf Books

- The Voyage Out (1915)

- Night and Day (1919)

- Jacob’s Room (1922)

- Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

- To the Lighthouse (1927)

- Orlando: A Biography (1928)

- A Room of One’s Own (1929)

- The Waves (1931)

- Flush: A Biography (1933)

- The Years (1937)

- Roger Fry: A Biography (1940)

- Between the Acts (1941)

Famous Virginia Woolf Quotes

- “If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.”

- “When you consider things like the stars, our affairs don’t seem to matter very much, do they?”

- “Words do not live in dictionaries, they live in the mind.”

- “Humor is the first of the gifts to perish in a foreign tongue.”

- “Time, unfortunately, though it makes animals and vegetables bloom and fade with amazing punctuality, has no such simple effect upon the mind of man.”

- “One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.”

- “Nothing has really happened until it has been described.”

- “So long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters; and whether it matters for ages or only for hours, nobody can say.”

- “Fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners.”

- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- English Literature, 20th cent. to the Present: Biographies

Woolf, Virginia

Virginia woolf.

BORN: 1882, London, England

DIED: 1941, Lewes, Sussex, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS: Mrs. Dalloway (1925) To the Lighthouse (1927) Orlando (1928) A Room of One's Own (1929)

One of the most prominent literary figures of the twentieth century, Virginia Woolf is chiefly renowned as an innovative novelist. She also wrote book reviews, biographical and autobiographical sketches, social and literary criticism, personal essays, and commemorative articles treating a wide range of topics. Concerned primarily with depicting the life of the mind, Woolf revolted against traditional narrative structures and developed her own highly individualized style of writing.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Early Life in an Unconventional and Literary Atmosphere Born in London, Virginia Woolf was the third child of Julia and Leslie Stephen . Although her brothers, Thoby and Adrian, were sent to school, Virginia and her sister, Vanessa, were taught at home by their parents and by tutors. Theirs was a highly literary family. Woolf received no formal education, but she was raised in a cultured atmosphere, learning from her father's extensive library and from conversing with his friends, many of whom were prominent writers of the era.

Formation of the Bloomsbury Group Following the death of her father in 1904, Woolf settled in the Bloomsbury district of London with her sister and brothers. Their house became a gathering place where such friends as J. M. Keynes, Lytton Strachey , Roger Fry, and E. M. Forster congregated for lively discussions about philosophy, art, music, and literature. A complex network of friendships and love affairs developed, serving to increase the solidarity of what became known as the Bloomsbury Group. Here she met Leonard Woolf, the author, politician, and economist whom she married in 1912. Woolf flourished in the unconventional atmosphere that she and her siblings had cultivated.

Financial Need Catalyzes Literary Output The need to earn money led her to begin submitting book reviews and essays to various publications. Her first published works—mainly literary reviews—began appearing anonymously in 1904 in the Guardian , a weekly newspaper for Anglo-Catholic clergy. Woolf's letters and diaries reveal that journalism occupied much of her time and thought between 1904 and 1909. By the latter year, however, she was becoming absorbed in work on her first novel, eventually published in 1915 as The Voyage Out .

The Hogarth Press In 1914, World War I began, a devastating conflict that involved carnage on an unprecedented scale. It involved nearly every European country and, eventually, the United States . About twenty million people were killed as a direct result of the war. Nearly a million British soldiers died (similar losses were experienced by all the other warring nations). In 1917, while England was in the midst of fighting World War I , Woolf and her husband cofounded the Hogarth Press. They bought a small handpress, with a booklet of instructions, and set up shop on the dining room table in Hogarth House, their lodgings in Richmond. They planned to print only some of their own writings and that of their talented friends. Leonard hoped the manual work would provide Virginia a relaxing diversion from the stress of writing.

It is a tribute to their combined business acumen and critical judgment that this small independent venture became, as Mary Gaither recounts, “a self-supporting business and a significant publishing voice in England between the wars.” Certainly being her own publisher made it much easier for Virginia Woolf to pursue her experimental bent but also enabled her to gain greater financial independence from what was at that time a male-dominated industry. Like Woolf, many British women joined the professional work force in an increased capacity during World War I, capitalizing on England's need for heavy industry to support its armed forces.

Successful Experiments This philosophy of daring and experimental writing is shown in her self-published works. While the novel Night and Day (1919) is not astylistic experiment, it deals with the controversial issue of women's suffrage, or right to vote—a right championed by Woolf. At the time of its publication, English women over the age of thirty had just finally received voting rights; it would still be another decade before women held the exact same voting rights as men. Where Woolf might have had difficulty finding another publisher for a book dealing with such a subject, access to Hogarth Press left her free to deal with whatever subject matter she saw fit.