Case Studies of Intradialytic Total Parenteral Nutrition in Nocturnal Home Hemodialysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Nephrology, University Health Network, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 2 Division of Gastroenterology, University Health Network, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 3 Division of Nephrology, University Health Network, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 35798187

- DOI: 10.1053/j.jrn.2022.06.009

The standard use of intradialytic parenteral nutrition has yielded heterogeneous clinical results. Confounders include patient selection, limited dialysis sessional duration, and frequency. Nocturnal home hemodialysis provides an intensive form of kidney replacement therapy (5 sessions per week and 8 hours per treatment). We present a series of 4 nocturnal home hemodialysis patients who required intradialytic total parenteral nutrition (IDTPN) as their primary source of caloric intake. We describe the context, effectiveness, and complications of IDTPN in these patients. Our patients received a range of 1200 to 1590 kCal (including 60 to 70 g of amino acids) with each IDTPN session for up to 27 months. As the availability of home hemodialysis continues to grow, the role of supplemental or primary IDTPN will require further research for this vulnerable patient population.

Keywords: Muscle quality; fluid hydration; hemodialysis; ultrasound.

Copyright © 2022 National Kidney Foundation, Inc. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Hemodialysis, Home*

- Kidney Failure, Chronic* / complications

- Kidney Failure, Chronic* / therapy

- Parenteral Nutrition / methods

- Parenteral Nutrition, Total

- Renal Dialysis / methods

Parenteral Nutrition

Welcome to the Parenteral Nutrition section! Throughout this section, an inpatient case study will be used to enhance your learning and comprehension of parenteral nutrition. You will learn what information to gather for your assessment, how to interpret that data to form a nutrition care plan, how to implement your patient’s care plan, and what to look for when following-up and evaluating your plan. As you progress through the content, please keep in mind that the nutrition care process model used here is dynamic and not a linear, step-by-step process. The case study used here is an example, and not all cases will follow the same path.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of the section you will be able to:

- Identify indications, contradictions, and routes of support to determine the requirement for parenteral nutrition.

- Identify the routes, sites of delivery, and delivery methods of parenteral nutrition.

- Identify how to gather clinical, anthropometric, biochemical, and dietary data necessary to complete a parenteral nutrition assessment.

- Determine a patients energy, protein, and fluid needs using data from the initial assessment.

- Interpret biochemical values, including sodium, potassium, phosphorous, calcium, magnesium, albumin, BUN/urea, and creatinine.

- Identify the role of a total parenteral nutrition (TPN) team or the interdisciplinary team.

- Choose an appropriate parenteral nutrition formulation and plan for a patient.

- Identify a patient a risk of refeeding syndrome and implement procedures to prevent it.

- Identify the complications of parenteral nutrition and understand the appropriate management procedures.

- Understand the key factors in appropriately monitoring the parenteral nutrition care plan.

- Evaluate the nutrition care plan using assessment data relevant to the patients concerns, including malnutrition, symptom management, parenteral nutrition changes, medications, supplements, and the medical plan.

Preparation for Dietetic Practice Copyright © by Megan Omstead, RD, MPH is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,951,249 articles, preprints and more)

- Free full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Total Parenteral Nutrition

Author information, affiliations.

- Puckett Y 1

Study Guide from StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) , 10 Jul 2020 PMID: 32644462

Books & documents Free full text in Europe PMC

Abstract

Free full text .

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Marah Hamdan ; Yana Puckett .

Last Update: July 4, 2023 .

Continuing Education Activity

Total parenteral nutrition is a medication used to manage and treat malnourishment. It is in the nutrition class of drugs. Total parenteral nutrition is indicated when there is impaired gastrointestinal function and contraindications to enteral nutrition. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is when the IV administered nutrition is the only source of nutrition the patient is receiving. This activity describes the indications, action, and contraindications for total parenteral nutrition as a valuable agent in managing malnourishment and the nonfunctional gastrointestinal system. In addition, this activity will highlight the mechanism of action, adverse event profile, and other key factors (e.g., off-label uses, dosing, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, monitoring, relevant interactions) pertinent for members of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with malnourishment and nonfunctional gastrointestinal system and related conditions.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for total parenteral nutrition.

- Describe the potential adverse effects of total parenteral nutrition

- Review the appropriate monitoring of total parenteral nutrition.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance total parenteral nutrition and improve outcomes.

Indications

Parenteral nutrition is the intravenous administration of nutrition outside of the gastrointestinal tract. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is when the IV administered nutrition is the only source of nutrition the patient is receiving. Total parenteral nutrition is indicated when there is impaired gastrointestinal function and contraindications to enteral nutrition. Enteral diet intake is preferred over parenteral as it is inexpensive and associated with fewer complications such as infection and blood clots but requires a functional GI system. [1] According to Chowdary and Reddy (2010), TPN has several indications. [2] These include:

- Chronic intestinal obstruction as in intestinal cancer [3]

- Bowel pseudo-obstruction with food intolerance.

- TPN can also be used to rest the bowel in cases of GI fistulas with high flow [4]

- When an infant’s gastrointestinal system is immature or has a congenital gastrointestinal malformation

- When there is a post-operative bowel anastomosis leak

- When the patient is unable to maintain nutritional status due to severe diarrhea or vomiting

- Small bowel obstruction

- Hypercatabolic states due to sepsis, polytrauma, and major fractures [5]

- An anticipated period of nothing by mouth (NPO) status greater than seven days as in patients with inflammatory bowel disease exacerbations as well as critically ill patients [6]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates parenteral nutrition in the United States, and the FDA requires statistically significant evidence of the efficacy and safety of parenteral nutrition products. Consequently, there are postapproval clinical trial requirements for parenteral nutrition products. [7]

Mechanism of Action

TPN is a mixture of separate components which contain lipid emulsions, dextrose, amino acids, vitamins, electrolytes, minerals, and trace elements. [8] [9] Clinicians should adjust TPN composition to fulfill individual patients' needs. The main three macronutrients are lipids emulsions, proteins, and dextrose.

Lipid Emulsions

- It provides calories and prevents fatty acid deficiency. Essential fatty acid deficiency may develop within three weeks of fat-free TPN. [2]

- 25% to 30% of the total calories are in the form of lipids.

- Healthy adult requirements are 0.8 to 1 gm of protein/kg/day.

- This change is based on the condition of the patient. Critically ill patients require 1.5 gm/kg/day, patients with chronic renal failure are given 0.6 to .0.8 gm/kg/day, and patients with acute hepatic encephalopathy need temporary protein restriction to 0.8 gm/kg/day, patients on hemodialysis need 1.2 to 1.3 gm/kg/day. [2]

Carbohydrate

- Provided through dextrose monohydrate in a variety of concentrations, most commonly 40,50, and 70%

- Glucose utilization maximum rate is 5 to 7 mg/kg/min.

- Excess carbohydrate supplementation can result in hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia.

Electrolytes, Trace Elements, and Vitamins are Micro-nutrients

- Trace elements and vitamin dosing can be according to recommended daily requirements.

- Sodium: 100 to 150 mEq

- Magnesium: 8 to 24 mEq

- Calcium: 10 to 20 mEq

- Potassium: 50 to 100 mEq

- Phosphorus: 15 to 30 mEq

Total nutrition is an admixture, a 3-in-1 solution of the three macronutrients (dextrose, amino acids, lipid emulsions).

- A 3-in-1 solution and intravenous lipid emulsions) mixed with electrolytes, trace elements, vitamins, and water. Parenteral solution with only dextrose and amino acids with a separate intravenous lipid emulsions infusion, the 2-in-1 solution, has also been previously used. [8] Research has shown TNA to be the standard of care for adult TPN.

The currently used TPN amino acid mixture continues to be incomplete, with only 19 amino acids. [10] The non-essential amino acid glutamine has been used as a complement to TPN to complete the amino acid content of TPN (Glutamine 8 to 10% in PN is a compliment). Surgical critical care patients have decreased glutamine levels on admission, which continues to decline until the third hospital ICU day. Per a study by Tsuji, both high ≥700 nmol/mL and low <400 nmol/mL of glutamine levels in ICU patients showed a statistical correlation with increased mortality in those patients between 400 to 700 nmol/mL. [11] Glutamine should serve as a complement to TPN rather than pharmaco-nutrition at supra nutritional doses. Patients who should not receive glutamine complementation above what may be present in basal TPN, as referenced by Heyland et al., include patients in septic shock, hemodynamic instability with increased vasopressor doses, and patients with renal failure. [12]

The pharmaceutical perspective of parenteral nutrition and Y site incompatibility:

- Parenteral nutrition(PN) mixtures should be physicochemically and microbiologically stable. In addition, the preparation of TPN requires analyzing their composition and any interactions that might occur during preparation, storage, and administration. [13]

- Hospitalized patients requiring parenteral nutrition (PN) need intravenous medications. In one study, researchers evaluated the physical compatibility of various drugs with neonatal total parenteral nutrition (TPN) solution during Y-site administration. In this study, amiodarone, phenobarbital, and rifampin formed visible precipitation with neonatal TPN and should not be coadministered via Y-site injection. [14]

- Clinicians should refer to individual compatibility of drugs with parenteral nutrition to avoid potential hazards such as crystal formation. [15]

Administration

Total parenteral nutrition administration is through a central venous catheter. A central venous catheter is an access device that terminates in the superior vena cava or the right atrium and is used to administer nutrition, medication, chemotherapy, etc. Establishing this access could be through a peripheral inserted central catheter (PICC), central venous catheter, or an implanted port. [16]

Clinicians can insert a PICC line into the basilic, cephalic, brachial, or median cubital vein. The basilic vein is preferable due to its larger size and superficial location. The catheter courses through the basilic into the axillary vein, to the subclavian vein, to settle in the superior vena cava. [17] PICC lines could be used when TPN is administered for several weeks to months.

The insertion of central venous catheters can be through one of the large three central veins: femoral vein, subclavian vein, or internal jugular vein. Central venous catheters are used when administering TPN for several months to years. [18]

An implanted port is a device implanted under the chest's skin with an attached catheter inserted into the superior vena cava. Implantable ports have been used when administering TPN for years. [18]

Due to its high osmolarity, total parenteral nutrition is not administered through a peripheral intravenous catheter (Peripheral Parenteral Nutrition, PPN). PPN osmolarity needs to be less than 900 mOsm. The lower concentration necessitates larger volume feedings, and high-fat content is necessary. High osmolarity irritates peripheral veins; hence TPN is given through central venous access.

Use in Specific Patient Population

Patients with Hepatic Impairment: Rapid initiation of parenteral nutrition is recommended in moderately or severely malnourished cirrhotics who cannot be nourished sufficiently by either oral or enteral route. Parenteral nutrition is recommended in patients with unprotected airways and encephalopathy (HE) due to the risk of aspiration in these patients. In patients with liver disease, substantial inter-individual variability exists. Hence resting energy expenditure (REE) should be calculated using indirect calorimetry, if available. [19] [20]

Patients with Renal Impairment: Patients with renal impairment, especially patients with ESRD, are at increased risk of nutritional disorders. In hospitalized patients with AKI or CKD requiring medical nutrition therapy, indirect calorimetry should be used to estimate energy expenditure to guide nutritional therapy and avoid under or overfeeding. In case of contraindications to ONS and EN, PN(parenteral nutrition) should be started within three to seven days. To promote positive nitrogen balance in acute kidney injury, clinicians should adjust protein intake according to catabolic rate, renal function, and dialysis losses. Common laboratory abnormalities associated with prolonged RRT include hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia. Hence electrolyte intake in patients should be adjusted by monitoring serum concentrations. Trace elements should be monitored and supplemented as there are increased requirements during ESRD, critical illness, and extensive effluent losses during renal replacement therapy(RRT). Clinicians should give specific attention to selenium, zinc, and copper. [21] [22]

Breastfeeding Considerations: A literature review suggests that breastfeeding women receiving total parenteral nutrition have breastfed their infants. In addition, using intravenous amino acids in parenteral nutrition in postpartum mothers may hasten the onset of lactation and improve weight gain in breastfed infants. [23]

Pregnancy Considerations: The association between low pre-pregnancy BMI and poor weight gain in pregnancy with adverse perinatal outcomes has been well described; still, information regarding the outcome of pregnancy in women on TPN is lacking. Substantial advancements in TPN technology have now minimized maternal safety concerns. [24] However, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines, Clinicians should utilize enteral tube feeding to provide nutritional support to a pregnant woman, as life-threatening complications such as sepsis and thromboembolism associated with parenteral nutrition have been reported. In addition, clinicians can insert peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) lines to avoid some complications associated with central lines. However, PICC lines are still associated with substantial morbidity and should be used only when enteral feeding is not feasible. [25]

COVID-19 Considerations: Critically ill intubated patients with COVID-19 usually require a prolonged ICU stay and are prone to significant energy and protein deficit. Therefore, when enteral nutrition is not possible, there is a need to switch to parenteral nutrition. The significant change in prescribing PN therapy was a change from soybean oil-based lipid injectable emulsions (ILEs) to alternative ILE products with a lower inflammation profile. In addition, the requirement for multi-chamber-bag PN products increased during the pandemic. This practice reduced pharmacist and pharmacy technician time in the sterile compounding area to decrease the use of PPE and divert resources to other pharmacy responsibilities. For parenteral nutrition, nurses guard the tubing with a protective layer, a critical consideration from an infection-control perspective. In addition, for patients with COVID-19, consolidation of timing for medication administration and parenteral nutrition is recommended. Finally, patients with COVID-19 are prone to develop hypertriglyceridemia; hence serum triglyceride concentrations are obtained at baseline and within 24–48 hours of initiating parenteral nutrition. [26]

Adverse Effects

The main adverse effects can be metabolic abnormalities, infection risk, or associated venous access.

Venous Access: It is associated with the insertion of the central line catheter.

- Pneumothorax

- Air embolism

- Venous thrombosis

- Vascular injury [27] [2]

Catheter Site Infections

- Central line-associated bloodstream infection(CLABSI) [28]

- Local skin infection at insertion or exit site

Metabolic Abnormalities

- Refeeding syndrome in chronic alcoholic patients and in patients who have nothing-by-mouth status (NPO) for more than 7 to 10 days

- Hyperglycemia

- Sudden discontinuation can lead to hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia is correctable with 50% dextrose.

- Serum electrolyte abnormalities

- Wernicke’s encephalopathy [29] [2]

- Parenteral-associated cholestasis

Due to safety concerns and the complexity of administration, parenteral nutrition is considered high risk by the ISMP(Institute for Safe Medication Practice). [30]

Contraindications

According to Maudar (2017), TPN is generally contraindicated in the following conditions:

- Infants with less than 8 cm of the small bowel

- Irreversibly decerebrate patients

- Patients with critical cardiovascular instability or metabolic instabilities; such instabilities require correction before administering intravenous nutrition.

- When gastrointestinal feeding is possible

- When the nutritional status is good, only short-term TPN is needed

- The lack of a therapeutic goal, as TPN should not be used to prolong life when death is unescapable.[5]

Boxed Warning: FDA has issued a boxed warning for some intravenous fat emulsions due to increased risk of death in preterm neonates related to intravascular fat accumulation in the lungs. Therefore clinicians must be cautious in choosing the right TPN therapy for preterm infants according to evidence-based guidelines. [31]

ASPEN (American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition) evidence-based guidelines suggest using a 1.2-micron in-line filter. Although 1.2-micron filters are not advised for use as standard infection control, these filters are efficacious in preventing Candida albicans infection in patients receiving parenteral nutrition. [32]

Per the American College of Gastroenterology, the identification of critically ill patients who can benefit from parenteral nutrition should be made using a validated scoring system such as Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) or Nutrition Risk in Critically ill (NUTRIC) score. [20]

Per Maudar 2017, several variables require monitoring while on TPN. [5] Among these are:

- Intake and output 12-hour charts

- Urine sugar monitoring every 8 hours

- Serum electrolytes: daily sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, calcium, and chloride values

- Serum creatinine and blood urea daily values

- Serum protein levels twice daily

- Liver function tests twice daily

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) guidelines also offer monitoring guidelines. [33] These include:

- Patients who recently received TPN should be monitored daily until stable. They require frequent monitoring if metabolic abnormalities are detected or the patient has a risk of refeeding syndrome. Refeeding syndrome can occur in severely malnourished and cachectic individuals when feeding is reintroduced and can lead to severe electrolyte instabilities. Refeeding syndrome can correlate with hypophosphatemia, respiratory distress, rhabdomyolysis, and acute kidney injury. Prevention of refeeding syndrome is critical and achievable with a slower initial infusion of TPN than expected. [34]

- Unstable and critically ill patients should be monitored daily until stable.

- Stable hospital patients with no formulation changes for one week should be monitored every 2 to 7 days.

- Stable hospital, home, or long-term care setting, patients with no formulation changes for one week should be monitored every 1 to 4 weeks if clinically stable.

Generally, the toxicity of TPN is related to the individual toxicity of its components. Increased caloric amounts due to TPN glucose and lipid excess can lead to hepatic toxicity; this risk can decrease by using decreased glucose and greater lipid content. A glucose infusion rate greater than 5 mg/Kg/min can result in a fatty liver because increased glucose in the blood induces hepatic lipogenesis, and increased glucose levels induce increased insulin levels leading to more lipogenesis. [35] This effect is preventable by decreased dextrose dosage to under 5 g/kg day, less than 5mg/kg min, cyclic PN for 8 hours as it decreases excessive insulin secretion and substituting 30% of dextrose energy with lipids.

Parenteral nutrition supplementation rather than total parenteral nutrition is harmful to pediatric patients in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Clinicians should withhold parenteral nutrition supplementation in the first week in the PICU independent of age or nutritional status; this is because amino acids in the PN suppress the autophagy process needed for cellular damage removal. Excess amino acids a shuttled to urea production. Increased urea levels can pose harm to the kidney and liver. [36]

Long-term usage of TPN, ranging from weeks to months, can be associated with the rare complication of manganese toxicity. Manganese exposure via TPN is characterized by high bioavailability due to bypassing the GI tract regulatory mechanisms. Over time, this high manganese concentration leads to its deposition in the liver, brain, and bone. However, the brain is most likely to be affected as manganese will deposit and affect the globus pallidus and striatum of the basal ganglia. Manganese preferentially affects dopaminergic neurons in the basal ganglia, resulting in extrapyramidal symptoms similar to Parkinson's disease. Idiopathic Parkinson's disease can be differentiated based on the location of neurons affected, i.e., in the substantia nigra. [37]

Peroxide(Reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation in parenteral nutrition(PN) happens when PN are exposed to light and phototherapy. Premature infants are susceptible to the consequences of peroxide formation in PN (e.g., bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, and retinopathy of prematurity). Hence, the ASPEN guidelines suggest photoprotection of parenteral nutrition products beginning from the compounding process and continuing until the entire PN is administered. [38]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

TPN administration needs a well-coordinated health care team with an interprofessional approach. The team includes:

- Nutrition nurse specialist

The clinician determines the treatment and the form of needed nutrition. The clinician coordinates care with the patient's primary health care team. The pharmacist provides sterile parenteral nutrition. The pharmacist advises on the stability of the compound and any drug/nutrient interactions that may arise. The dietician assesses the patient's nutritional status, calculates the daily requirement, and designs the feeding regimen. The nutrition nurse specialist supervises catheters and tube care. They are the patient's advocate and train the patient/caretaker to manage the tubes at home. Extended staff includes: social workers, occupational therapists, and wound management nurses. [39] All interprofessional team members must engage in open communication and accurately document any changes in patient status so everyone involved in care can have access to the most accurate and current information from which to make care decisions.

The ASPEN guidelines recommend comprehensive education and competency for clinicians, pharmacists, dieticians, and pharmacy technicians. The study revealed that interprofessional education programs and collaboration could significantly optimize parenteral nutrition-related patient safety and outcomes. [40] [Level 5]

Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Marah Hamdan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Yana Puckett declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Citations & impact

This article has not been cited yet.

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics.

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Pan A , Gerriets V

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) , 20 Aug 2019

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 31424836

Yip DW , Gerriets V

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) , 03 Mar 2020

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 32119447

Pramipexole

Singh R , Parmar M

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) , 04 Jun 2020

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 32491471

Rivastigmine

Patel PH , Gupta V

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 32491370

Antiemetic Antimuscarinics

Migirov A , Yusupov A

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) , 16 Oct 2019

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 31613451

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Overview of Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN)

Giving Nutrition Through the Veins

Most people receive the energy and nutrients they need through their diets, but sometimes this is not possible for medical reasons. Parenteral nutrition gives a person the nutrients and calories they need through a vein instead of through eating.

With total parenteral nutrition (usually called TPN), a person gets 100% of the nutrition they need each day through a vein.

Parenteral nutrition can be given temporarily or for a longer time. In the United States, around 30,000 people rely completely on feedings given directly through their veins to get the nutrition they need.

Jodi Jacobson / iStock/ Getty Images Plus / Getty Images

What Is TPN?

A person who is on total parenteral nutrition receives all the nutrients and energy they need through an intravenous (IV) line. The nutrients enter through the veins and travel through the blood vessels to the entire body.

Normally, the organs of the gastrointestinal tract (especially the small intestine ) absorb the calories and nutrients the body needs. Parenteral nutrition completely bypasses the stomach and intestines. Instead, the nutrients are made available directly to the veins, from which they can be pumped all over the body.

You might also hear the term “partial parenteral nutrition.” This refers to someone who is receiving some, but not all, of their total nutrition through their veins. A doctor may prefer this method if a person's gut is impaired but can still perform some digestion.

Parenteral Nutrition vs. Enteral Nutrition

Another option is “enteral” nutrition. Even though “enteral” sounds a lot like “parenteral,” they are not the same. “Enteral” comes from the Greek word meaning “intestine.” The suffix “para” means, roughly, “beyond.”

A person receiving enteral nutrition is absorbing nutrients through their gastrointestinal tract, but a person receiving parenteral nutrition is not.

Technically speaking, normal eating is a type of enteral nutrition. However, the term is more often used to describe medical interventions that allow someone to get nutrition into their gastrointestinal tract in other ways (“tube feeding”).

For example, enteral nutrition includes nasal or oral tubes that run down to the stomach or intestines from the nose or mouth. Other examples are gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes (G-tubes and J-tubes), which are medically inserted into the stomach or part of the small intestine, respectively, to allow food to be administered there.

Why Enteral Is Preferred

When an alternative method of feeding is needed, doctors prefer to use enteral feeding methods instead of parenteral whenever possible. One reason is that enteral nutrition does not disrupt the body’s normal physiological processes the way parenteral nutrition does.

The body is specifically adapted to absorb and process nutrients through the lining of the intestines. Because of these physiological differences and some other factors, enteral feeding has less risk of serious complications compared with parenteral feedings.

For example, parenteral nutrition causes more inflammation than enteral nutrition, and it’s harder for the body to regulate its blood sugar levels with parenteral nutrition. Parenteral nutrition is also more complicated and expensive than enteral feeding.

An enteral method might be recommended for someone who was having difficulty swallowing after having a stroke but who has a normally functioning gastrointestinal tract. In contrast, parenteral feeding might be necessary if a person is having trouble absorbing calories and nutrients through their gastrointestinal tract.

Who Might Need TPN?

Any person who is unable to get enough calories through their gastrointestinal tract might need to receive TPN. Some medical situations that might require TPN include:

- Cancer (particularly of the digestive tract) or complications from cancer treatment

- Ischemic bowel disease

- Obstruction of the digestive tract

- Inflammatory bowel disease (such as Crohn’s disease )

- Complications from previous bowel surgery

Some premature infants also need to receive TPN temporaril y because their digestive tracts are not mature enough to absorb all the nutrients they need.

Some hospitalized people need TPN if they are unable to eat for an extended period and enteral methods are not possible.

How Is TPN Given?

If you need to receive TPN, your medical team will need to have access to your veins. A catheter —a long thin tube—will be put in some part of the venous system. The careful placement of a catheter is done in the hospital while a person is under heavy sedation or anesthesia.

Some catheter and TPN delivery methods are better suited for temporary use and others for more long-term use.

Tunneled Catheter

Depending on your situation and personal preferences, you might opt to get a tunneled catheter, which has a segment of the tube outside the skin and another portion under the skin.

Port-a-Cath

Another option is an implanted catheter (sometimes called a “port-a-cath,” or just a “port”). In this case, the catheter itself is completely beneath the skin and is accessed with a needle to infuse the parenteral nutrition.

To administer TPN, a health professional can use either type of catheter to connect to an external bed of fluids containing the necessary nutrients and calories. This can be done in different places, such as one of the main veins in the neck or upper chest.

A PICC line (peripherally inserted central catheter) is another choice, particularly when a person will need to use TPN for a longer time.

With a PICC line, the entry point that is used to deliver the TPN is a vein in the arms or legs, but the catheter itself threads all the way to a larger vein deeper inside the body.

TPN is started in a hospital setting. A person will often be hooked up to TPN to receive the infusion steadily over 24 hours.

Some people will need to continue to receive TPN even after they go home from the hospital. They may get nutrition over eight- to 12-hour blocks.

What Does TPN Contain?

TPN is designed to replace all the important nutrients that a person would normally be getting through their diet.

These components include:

- Carbohydrates

- Vitamins (e.g., vitamin A)

- Electrolytes (e.g., sodium)

- Trace elements (e.g., zinc)

There are many specific formulations available for TPN. Not everyone gets the same components in the same amounts. The TPN that you need will depend on several factors, such as your age and any medical conditions that you have.

Your nutritional team will also determine how many calories you need each day . For example, a person with obesity might be given a slightly smaller number of calories and may even lose a little weight on TPN.

In contrast, nutritionists would likely give a solution that is much higher in calories to someone who is significantly underweight.

Your medical team will carefully tailor your TPN to you based on your specific circumstances, and they will modify the formulation as needed. This helps reduce the risk of complications from TPN.

A person receiving parenteral nutrition—but not total parenteral nutrition—might only get some of these elements, such as carbohydrates and water.

Laboratory Assessment and Monitoring for TPN

Before starting TPN, your medical team will assess whether TPN is safe and necessary for you. They’ll also need to do some blood tests to help them decide on the ideal formulation.

You’ll need to get certain blood tests at regular intervals after you start TPN to help your medical team monitor for and prevent medical complications.

Blood tests that you might need include:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Electrolytes

- Blood urea nitrogen (to monitor kidney function)

- Blood sugar (glucose) levels

- Liver tests

The blood tests generally need to be done more often at first (sometimes multiple times a day). As a person’s medical situation stabilizes, testing is not needed as frequently. The specific tests that you need will depend on your medical situation.

What Are the Side Effects and Risks of TPN?

Some people still get hungry while they are on TPN. The brain is not getting the signals that it normally does to trigger a feeling of fullness. The sensation tends to diminish with time.

Other people experience nausea from TPN, which is more likely when they have an intestinal blockage.

Catheter Issues

The placement of the catheter can cause problems, although they are rare.

Some possible complications of catheter placement include:

- Air embolism

- Pneumothorax

- Hitting an artery instead of a vein

- Nerve damage from incorrect insertion

- Catheter fragment embolism

- Cardiac tamponade (very rare but life-threatening)

Other Catheter-Related Problems

Catheters can also cause problems after they have been placed, including infections and, less commonly, blood clotting issues.

Catheter Infections

Catheter infections are also a serious problem and one that clinicians try very hard to prevent. One of the first steps to prevent catheter infections is to ensure that the person accessing the line uses good hand hygiene and cleans the area properly before accessing the line.

Health professionals use a strict protocol to keep germs from entering the catheter line.

An infected catheter often requires antibiotic treatment and rehospitalization if a person is already at home. A person might also need to have a new procedure to replace their catheter, which carries its own risk for complications and is also expensive.

Blood Clots

Blood clots in the vessels near the catheter are another serious risk. These clots can sometimes cause symptoms like swelling of the arm or neck.

Catheter-related blood clots can also lead to complications such as pulmonary embolism and infection, as well as post-thrombotic syndrome. This complication can cause long-term swelling and pain in the affected area.

Problems From TPN Infusions

Being on TPN even for a short time comes with risks related to the different levels of some compounds in the body, such as electrolytes and vitamins.

Electrolyte and Fluid Imbalances

Electrolyte and fluid imbalances can be a problem for people receiving TPN. The body has several important electrolytes (minerals that are dissolved in fluids) that are critical for many of the body's basic physiological processes.

Important electrolytes in the body include sodium, potassium, and calcium, as well as some that are present in smaller amounts, such as iron and zinc. If the concentration of these electrolytes in the blood is too high or too low, it can cause serious health problems (such as heart rhythm issues).

The body may have more difficulty regulating the amount of these substances in the body because of how TPN is delivered. People on TPN also often have serious medical issues that make it difficult to predict exactly how much of these substances to deliver as part of the TPN.

Your medical team will carefully monitor the amount of these substances in your blood and adjust your TPN formula as necessary. That’s part of why frequent blood tests are needed for people on TPN, especially when it is first started.

Vitamins and Blood Sugar

The amounts of certain vitamins in the body (such as vitamin A) can also be harder to control when a person is on TPN. Another concern is the level of sugar in the person's blood (blood glucose levels).

A person on TPN can develop high blood glucose levels ( hyperglycemia ). One reason a person on TPN might be more likely to develop high blood sugar is that their body is under stress.

Sometimes a person can develop high blood sugar levels because the TPN formulation is delivering too much glucose or carbohydrates. However, doctors monitor a person for this carefully as part of regular blood tests.

Hyperglycemia can be addressed by altering the TPN formulation and/or potentially giving a person insulin, if needed.

Liver Function

Liver problems can also happen, especially in people who are using TPN for a long time. Some of these problems are not serious and go away when the TPN is stopped or adjusted.

However, in more serious cases, liver scarring (cirrhosis) or even liver failure can happen. A person's medical team will monitor their liver function carefully while they are on TPN.

There are some signs that can indicate complications related to TPN. If you have any of these symptoms while on TPN, call your doctor right away.

- Stomach pain

- Unusual swelling

- Redness at the catheter site

If you have serious symptoms, such as sudden chest pain, seek immediate emergency care.

Mental Health and Lifestyle Changes

People on TPN often experience diminished quality of life and may develop depression. It’s natural to miss the enjoyment of eating a good meal and the shared social connection with others that eating brings. It’s important to get the psychological support you need in whatever way feels right for you, such as through professional counseling.

If your medical situation has stabilized, you might be able to leave the hospital even if you are still on TPN. While many people feel better at home, it still presents challenges. For example, if you are hooked up to TPN overnight, you may need to wake several times to urinate.

If you opt to do your TPN during the day, it can interrupt your planned activities (although you can get it while working at your desk, for example). Still, getting TPN at home instead of in the hospital will usually improve a person's quality of life.

How Long Will I Need to Stay on TPN?

How long you need to have TPN depends on your underlying medical condition. Some hospitalized people need TPN for a relatively short time—such as a week to 10 days.

Other people may need TPN for months (e.g., for problems related to surgical complications), but they are eventually able to come off TPN. You may also eventually be able to reduce the amount of parenteral nutrition that you need.

If the medical issue requiring TPN cannot be resolved, a person might need to remain on TPN for the rest of their life.

Cleveland Clinic. Living on Liquids: How an IV Only Diet Works .

Kirby DF, Parisian K, Cleveland Clinic, American College of Gastroenterology. Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition .

Seres DS, Valcarcel M, Guillaume A. Advantages of enteral nutrition over parenteral nutrition . Therap Adv Gastroenterol . 2013;6(2):157-167. doi:10.1177/1756283X12467564

Oshima T, Pichard C. Parenteral nutrition: never say never . Crit Care . 2015;19 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S5. doi:10.1186/cc14723

Kirby DF. Improving outcomes with parenteral nutrition . Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) . 2012;8(1):39-41.

Doyle GR, McCutcheon JA. Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) . Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care. British Columbia Institute of Technology.

Wall C, Moore J, Thachil J. Catheter-related thrombosis: A practical approach . J Intensive Care Soc . 2016;17(2):160-167. doi:10.1177/1751143715618683

Gosmanov AR, Umpierrez GE. Management of hyperglycemia during enteral and parenteral nutrition therapy . Curr Diab Rep . 2013;13(1):155-162. doi:10.1007/s11892-012-0335-y

Nowak K. Parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease . Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020 Mar 26;15(2):59-62. doi:10.1002/cld.888

Pinto-Sanchez MI, Gadowsky S, McKenzie S, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life improve after one month and three months of home parenteral nutrition: A pilot study in a Canadian population . J Can Assoc Gastroenterol . 2019 Dec;2(4):178-185. doi:10.1093/jcag/gwy045

By Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD Dr. Hickman is a freelance medical and health writer specializing in physician news and patient education.

An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

1. Use quotes to search for an exact match of a phrase.

2. Put a minus sign just before words you don't want.

3. Enter any important keywords in any order to find entries where all these terms appear.

- The PSNet Collection

- All Content

- Perspectives

- Current Weekly Issue

- Past Weekly Issues

- Curated Libraries

- Clinical Areas

- Patient Safety 101

- The Fundamentals

- Training and Education

- Continuing Education

- WebM&M: Case Studies

- Training Catalog

- Submit a Case

- Improvement Resources

- Innovations

- Submit an Innovation

- About PSNet

- Editorial Team

- Technical Expert Panel

Total Parenteral Nutrition, Multifarious Errors

Case objectives.

- Define parenteral nutrition (PN).

- Describe the PN-use process.

- Identify potential PN-related medication errors.

- Describe methods to reduce PN-related errors.

Case & Commentary—Part 1

A 3-year-old boy on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) due to multiple intestinal resections was admitted to an academic medical center for anemia. At baseline, the boy was developmentally appropriate but quite fragile medically, with multiple recent admissions for anemia and infections. Unable to take anything by mouth, he was completely dependent on the TPN for his nutrition and fluid intake, and had been so for more than a year. The boy had been doing well at home when he began having small amounts of bloody output from his ostomy site. His mother (the patient's primary caretaker at home) brought him to the hospital and he was admitted for further evaluation of the anemia. At the time of admission he was continued on his home TPN regimen.

The patient described in this case was receiving parenteral nutrition (PN), a life-sustaining therapy for individuals who cannot maintain or improve their nutrition status through the oral/enteral route. Such therapy is used in patients of all ages and across care settings (from intensive care units to the home). More than 350,000 hospital stays per year include PN, and tens of thousands of patients continue PN use at home.( 1 ) During growth and development, PN is particularly important for children even when the PN solution does not provide the total nutrient needs of a patient. Anticipated adverse effects of PN include complications associated with intravenous access (e.g., thrombosis, bloodstream infection) and metabolic homeostasis (e.g., hyper- or hypoglycemia, fluid and electrolyte disorders). The risks associated with PN were addressed at a recent safety summit.( 2 )

High-Alert Medication, Complicated Process

What may be less well recognized is that PN has been characterized as a high-alert medication.( 3 ) High-alert medications, by definition, are those that involve risk for significant harm when used in error. As such, safeguards are required to minimize error risk from PN. Notably, a patient's daily PN admixture may contain at least 40 active ingredients, each with dosing implications and interaction potential.

Even though the ingredients in PN may carry some risk, errors in the PN-use process may lead to even more safety hazards. The PN-use process refers to the numerous steps in providing PN therapy, including prescribing, order review, preparation (compounding) and labeling, dispensing, administration, monitoring, as well as ongoing patient assessment and documentation of each step.( 1 ) These steps also involve numerous clinicians and caregivers from several departments, if not more than one organization or facility. Without a standardized process and full collaboration, many opportunities for error arise.( 4 ) Although errors are known to occur, a limited number of publications discuss them. Such errors may easily result in PN ranking among the top causes of medication error, but very few organizations capture these or share them internally.( 5 ) Moreover, unlike other high-risk medications, such as insulin or anticoagulants, limited literature describes the errors associated with PN use. A lone prospective observational study at one institution identified 74 PN-related medication errors (16 per 1000 PN prescriptions), with most occurring during transcription (39%), preparation (24%), and administration (35%).( 4 ) Because this group had a nutrition support team that wrote the prescriptions, no PN ordering errors were identified that resulted in an incorrect admixture or subsequent patient harm. This structure is optimal but atypical, and mistakes in the PN prescription and in the PN order review process may contribute to additional harm and a significant number of errors not captured in this study. Nearly 10% of the errors identified resulted in or contributed to patient harm.( 6 )

Making PN Use Safer

In addition to standardization of the process and the expertise of those involved, the number of patients receiving PN is a critical factor. Most institutions manage fewer than 10 PN patients daily, and more than 80% manage 5 or fewer pediatric patients requiring PN.( 5 ) Although this number may reflect appropriate PN use in favor of enteral nutrition when indicated, it also reveals the limited experience with PN in many organizations. The expertise needed to safely manage patients requiring PN is analogous to the expertise expected in the drug-use process for cancer chemotherapy. Health care providers involved with PN should be knowledgeable and skilled in patient PN management and error prevention. Caregivers involved with PN should work within an interdisciplinary setting that includes certified nutrition support nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, and physicians.( 7 )

Despite being a complex and high-alert medication, only 58% of organizations have safeguards in place to prevent patient harm from errors in the PN-use process.( 8 ) Approaches to improving the safety of PN can encounter significant organizational challenges but can be successful when based on published practice guidelines and standards.( 9 ) To help organizations minimize errors when using use this complex therapy, practice guidelines and recommendations (based on evidence or generally accepted practices) are available from national organizations. The American Society for Parenteral & Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) published the safe PN practice guidelines ( 10 ), but surveys have found that these guidelines have poor adherence.( 5,11,12 ) Meaningful reductions in error rates have been reported in a pediatric setting that adopted a standardized PN process.( 13 ) A revision of the 2004 ASPEN document is under way to provide graded, evidence-based clinical guidelines and a set of specific, actionable practice recommendations based on expert consensus.( 5 )

Transitions in Care and PN

Transitions in care create the opportunity for medication-related errors, which is certainly true for PN. One major contributing factor is the lack of prescription uniformity between institutions and across patient care settings; this variation is unmatched by any other medication in clinical practice. Myriad methods of ordering and labeling these complex PN preparations can be found. For example, varied units-of-measure can cause significant errors especially during transitions between hospital and home ( 14 ), at the least, errors involving the dosing of one or more of the dozens of active ingredients. Misinterpreted information from a PN label has led to error and patient harm in the transition from home to hospital.( 10 )

Ideally, one would hope the hospital described in the above scenario manages a high volume of patients on PN and adheres to the recognized national guidelines.( 10 ) Their staff members should be well-trained in all steps of the PN-use process, and the hospital should have a standardized process to reduce the risk for errors.

Case & Commentary—Part 2

On hospital day 2, the patient's serum sodium was noted by the team to be low at 130 mEq/L (normal 135–145 mEq/L). The team ordered to increase the amount of sodium in the TPN from 5.2 mEq/kg/day to 5.5 mEq/kg/day based on a standard formula. The new TPN with the increased sodium began infusing at 9:00 PM. Overnight, the boy complained of worsening abdominal pain, which was treated with increased doses of intravenous opiates. He also complained of headache (which he never had previously, per the mother) and was irritable and could not be consoled. In the morning, his labs were notable for serum sodium of 158 mEq/L, which was confirmed on recheck. At first, the acute hypernatremia was attributed to dehydration. On rounds, the resident caring for the patient examined the TPN bag to see how much sodium the boy was receiving. The TPN bag had a sodium concentration of 55 mEq/kg/day (a 10-fold increase of the intended sodium concentration of 5.5 mEq/kg/day). The TPN was immediately stopped and the boy was given free water intravenously to correct the severe hypernatremia. Correction took more than 48 hours. Fortunately, the boy did not experience any adverse consequences from the hypernatremia.

On formal review of the case, multiple errors led to the excess sodium infusion. This academic medical center had a functioning electronic health record (EHR) and computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system. However, due to the complexity of TPN orders, they were completed by hand and then scanned to the pharmacy to be entered by the pharmacist into the CPOE system. The order for the increased sodium was written appropriately on the paper order, which was scanned to the pharmacy. The pharmacist (who was specifically trained to enter TPN orders) inadvertently entered 55 mEq/kg/day into the computer. A second pharmacist (also trained in TPN) reviewed the order by standard protocol and did not catch the dosing error. The order was then sent to the contracted pharmacy that prepared the TPN for this hospital, and there an additional two TPN pharmacists did not recognize the error. Automatic warning flags popped up in the system regarding the high sodium dose but these were ignored and dismissed as this boy had more than 8 warnings each day for his TPN order, even when entered correctly.

Speaking with the pharmacists revealed that there was not only an error in transcription but they also had incorrectly perceived 55 mEq/ kg /day as 55 mEq/ L /day, an appropriate dose for an adult TPN order. Because of this, the TPN order was produced with the high sodium concentration and sent to the hospital. Two nurses verified the TPN order was accurate and appropriate at the bedside and also did not notice the error.

The error in this case involved a breakdown in oversight and system checks; breakdowns leading to medication errors is a familiar scenario.( 14 ) PN-related dysnatremia may be an all too common—though infrequently documented—error. As occurred in this case, multiple failures across the PN-use process are usually identified in retrospect as contributing to such errors. These can involve order entry and transcription errors, inappropriate abbreviations, dose designations or units-of-measure, PN component mix-ups (a bigger concern with ongoing shortages of many of these components), no warnings for catastrophic dose limits, catheter misconnections, and ineffective or nonexistent systems of independent double-checks.( 14 ) However, as happened here, the issue often begins with PN prescription.

A broad survey of institutions revealed that only 32.7% use a computerized order entry system (CPOE) system for PN.( 5 ) Even when CPOE is used for other medications, PN is seldom included. As in this case, most institutions still use handwritten orders requiring one or more error-prone transcription steps in the process. Available electronic health record (EHR) systems do not perform well when it comes to PN.( 16 ) Current CPOE systems need significant improvement in nutrition support content including decision support tools. Such tools would allow for real-time alerts to any macronutrient or micronutrient dosing below or above accepted values.( 5,16 ) Despite a number of obvious advantages over paper charts and handwritten orders, including the need for less order clarification or intervention, CPOE is of limited benefit if not built, customized, and subsequently optimized for all the users including those involved with PN.( 12,17 ) Significantly less order clarification/intervention is required when using an electronic system compared with handwritten.( 12,17 )

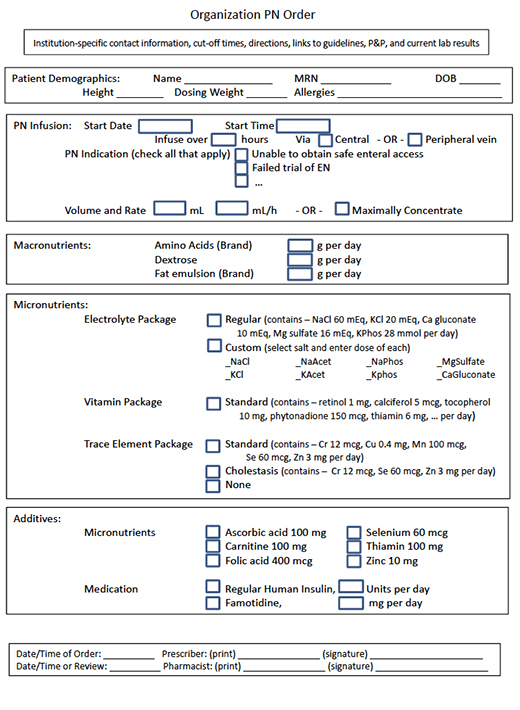

Fully integrating a CPOE system with pharmacy system can help prevent PN-related errors. Without such integration, PN should be prescribed using a standardized order template as an editable electronic document to avoid any handwritten orders ( Figure ). The need for any calculations or data conversion should also be avoided. Although unthinkable for most other medications, the need to specify the dose of each macronutrient and micronutrient to be included in the PN admixture varies considerably between institutions; mixed methods (mg/L for some contents, mg/kg/d for others) are sometimes even used within an institution.( 4 ) Due to the need for weight-based dosing of nearly everything, the use of mixed methods is more likely with pediatric patients. For example, electrolytes may be ordered either by salt or by ion, as well as varying units-of-measure (e.g., mEq or mmol per kg, per L, per day, or per total volume). The ordering process should include built-in decision support and alerts for when weight-based, population-specific dosing is out of range. In the absence of built-in decision support, the critical step of pharmacist review becomes paramount. In the present case, the need to specify the dose in mg/kg/day and the need to transfer the order from a paper form to the CPOE system contributed to the error.

A survey found that 23.1% of organizations do not dedicate pharmacist time to review and clarify these orders.( 5 ) The pharmacist should not only be trained to enter a PN order, but should be specifically knowledgeable in performing both a clinical review (e.g., dosing) and a pharmaceutical review (e.g., compatibility) of each PN order daily. Pharmacist interventions for all prescribing errors should then be documented in the permanent record. When knowledgeable pharmacists are involved, pediatric PN prescribing errors are identified and resolved at frequencies similar to those with other complex medications.( 17 )

Fewer than 10% of institutions have an interfaced electronic system for seamless transfer of a PN order from prescriber to pharmacy and the automated compounding device (ACD) that mixes the PN.( 5 ) Error rates for preparing complex admixtures (including PN) are 22% to 37% depending on method of preparation.( 15 ) ACDs are designed with the ability to provide users with alerts for dosing errors, however many institutions do not make full or appropriate use of these. Several reported PN-specific cases resulted from failure to incorporate built-in dosing limits in the ACD.( 15 ) These limits prevent inadvertent catastrophic electrolyte doses from being included in the preparation, but require the software to be appropriate for patient age and weight. In addition to optimizing the ACD, standard operating procedures should be in place to independently double-check every step in the preparation process.

Multiple warnings occurred daily with this patient's PN order, and ignoring them contributed to the error in this case. No warning flags should be ignored or dismissed no matter whether they appear each day; each should be recognized, clarified, and documented by the pharmacist. One PN-related fatality occurred when an infant received a 1000-fold excess of zinc because of a mix-up in units and another when an infant received a 60-fold overdose of sodium.( 15,18 ) The mix-up of dosing nutrients per kg or per day in another pediatric case was identified during PN infusion but before any adverse effect occurred.( 19 ) When not automated, a second pharmacist should be involved in evaluating the original order against what has been transcribed, prepared, and labeled for dispensing. Some have argued that institutions should use commercially available pre-made PN formulations (not mixed from scratch at the institution). Unfortunately, commercially available pre-made PN formulations are not safer in the absence of a standardized PN-use process.( 20 )

The final steps in the PN-use process are administration of PN and ongoing monitoring. In this case, the nurses checked the solution against the incorrectly entered order. Instead, nurses administering PN should independently check the label against the original order. If any of the ingredients listed on the label are out of sequence or have a different dose or units than the original order, then the process should stop for clarification back up the chain through the pharmacy to the prescriber. Patient safety is worth the time it takes to verify the order. It is the responsibility of the involved prescriber, pharmacist, nurse, and dietitian to recognize and report all PN-related medication errors—whether they reach the patient or not.

The use of a CPOE system with decision support that interfaces with the pharmacy computer system thereby averting a transcription step would have prevented this patient's PN error. In the absence of such a system, required documentation of the pharmacist's review to include comparing the dose of each component against an age-appropriate table of accepted values would have also made the error less likely. Furthermore, had the nurses checked the PN label against the original order, the error may have been caught at this late step in the PN-use process.

Take-Home Points

- PN is a high-alert medication requiring safety-focused policies, procedures, and systems.

- Institutions should incorporate all appropriate ASPEN clinical guidelines and best practices documents.

- Providers should take the opportunity to enhance patient safety and reduce PN-related medication errors by becoming directly involved in the oversight of this therapy.

- Institutions should collect and report all errors associated with PN internally and externally (through the ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program ); further information is available on the ASPEN Web site .

- Providers should document each step in the PN-use process so that any errors can be evaluated and corrective actions taken to improve the process.

Joseph I. Boullata, PharmD, RPh, BCNSP

Pharmacy Specialist, Clinical Nutrition Support Services

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Professor, Pharmacology & Therapeutics

University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing

Philadelphia, PA

Faculty Disclosure: Dr. Boullata has declared that neither he, nor any immediate member of his family, have a financial arrangement or other relationship with the manufacturers of any commercial products discussed in this continuing medical education activity. In addition, the commentary does not include information regarding investigational or off-label use of pharmaceutical products or medical devices.

1. Boullata JI. Overview of the parenteral nutrition use process. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:10S-13S. [go to PubMed]

2. Andris DA, Mirtallo JM, Guenter P, eds. ASPEN parenteral nutrition safety summit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(2 Suppl 2):1S-62S. [Available at]

3. ISMP's List of High-Alert Medications. Horsham, PA: Institute for Safe Medication Practices; 2012. [Available at]

4. Sacks GS, Rough S, Kudsk KA. Frequency and severity of harm of medication errors related to the parenteral nutrition process in a large university teaching hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:966-974. [go to PubMed]

5. Boullata JI, Guenter P, Mirtallo JM. A parenteral nutrition use survey with gap analysis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37:212-222. [go to PubMed]

6. Sacks GS. Safety surrounding parenteral nutrition systems. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:20S-22S. [go to PubMed]

7. Köglmeier J, Day C, Puntis JWL. Clinical outcome in patients from a single region who were dependent on parenteral nutrition for 28 days or more. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:300-302. [go to PubMed]

8. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care Edition. Results of ISMP survey on high-alert medications: differences between nursing, pharmacy, and risk/quality/safety perspectives. February 9, 2012;17:1-4. [Available at]

9. Boitano M, Bojak S, McCloskey S, McCaul DS, McDonough M. Improving the safety and effectiveness of parenteral nutrition: results of a quality improvement collaboration. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:663-671. [go to PubMed]

10. Mirtallo J, Canada T, Johnson D, et al; Task Force for the Revision of Safe Practices for Parenteral Nutrition. Safe practices for parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:S39-S70. [go to PubMed]

11. O'Neal BC, Schneider PJ, Pedersen CA, Mirtallo JM. Compliance with safe practices for preparing parenteral nutrition formulations. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:264-269. [go to PubMed]

12. Seres D, Sacks GS, Pedersen CA, et al. Parenteral nutrition safe practices: results of the 2003 American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition survey. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:259-265. [Available at]

13. AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. Standardized ordering and administration of total parenteral nutrition reduces errors in children's hospital. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 28, 2012. [Available at]

14. Kumpf VJ, Tillman EM. Home parenteral nutrition: safe transition from hospital to home. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:749-757. [go to PubMed]

15. Cohen MR. Safe practices for compounding of parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(Suppl 2):14S-19S. [go to PubMed]

16. Vanek VW. Providing nutrition support in the electronic health record era: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:718-737. [go to PubMed]

17. Hilmas E, Peoples JD. Parenteral nutrition prescribing processes using computerized prescriber order entry: opportunities to improve safety. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(Suppl 2):32S-35S. [go to PubMed]

18. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care Edition. Another tragic parenteral nutrition compounding error. April 21, 2011;16:1-3. [Available at]

19. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care Edition. Mismatched prescribing and pharmacy templates for parenteral nutrition (PN) lead to data entry errors. June 28, 2012;17:1-3. [Available at]

20. Poh BY, Benjamin S, Hayward TZ III. Standardized hospital compounded parenteral nutrition formulations do not guarantee safety. Am Surg. 2011;77:e109-e111. [go to PubMed]

Figure. Electronic PN Order Form

This project was funded under contract number 75Q80119C00004 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors are solely responsible for this report’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. None of the authors has any affiliation or financial involvement that conflicts with the material presented in this report. View AHRQ Disclaimers

Investigators find hospital error caused mother’s death in Brooklyn. January 24, 2024

The Impact of Light on Outcomes in Healthcare Settings. September 20, 2006

WebM&M Cases

Perspective

Mental mayhem: the peril of multitasking in medicine. July 17, 2019

A physician's personal experiences as a cancer of the neck patient: errors in my care. February 16, 2011

Doctors fear work caps for residents may be bad medicine. March 31, 2010

Improving doctor–patient communication in a digital world. February 17, 2016

UTMC nurse tossed out kidney, ruined it. National experts say error is rare. September 5, 2012

Medical disrespect. February 12, 2014

How one medical checkup can snowball into a ‘cascade’ of tests, causing more harm than good. January 22, 2020

200 epidural blunders admitted after three women die. July 5, 2006

Prevention Is Better Than Cure: Learning From Adverse Events in Healthcare. May 10, 2017

Designing for Patient Safety: Developing Methods to Integrate Patient Safety Concerns in the Design Process. October 24, 2012

505: Use only as directed. October 9, 2013

Old and overmedicated: the real drug problem in nursing homes. December 17, 2014

Officials investigate infants' heparin OD at Texas hospital. July 23, 2008

Disuse of system is cited in gaps in soldiers' care. April 11, 2007

Prevention of potential errors in resuscitation medications orders by means of a computerised physician order entry in paediatric critical care. February 28, 2007

Pediatric Diagnostic Safety: State of the Science and Future Directions. September 13, 2023

Pharmacist Staffing and the Use of Technology in Small Rural Hospitals: Implications for Medication Safety. January 25, 2006

Advances in Patient Safety and Medical Liability. September 6, 2017

Cognitive Informatics: Reengineering Clinical Workflow for Safer and More Efficient Care. August 21, 2019

Reducing Adverse Drug Events. March 6, 2005

ASPEN Parenteral Nutrition Safety Summit. March 21, 2012

Data quality associated with handwritten laboratory test requests: classification and frequency of data-entry errors for outpatient serology tests. November 18, 2015

Obstetric Care Consensus No. 5: Severe Maternal Morbidity: Screening and Review. May 9, 2018

IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work. August 9, 2017

The delivery of safe and effective test result communication, management and follow-up. September 27, 2023

Imagining improved interactions: patients' designs to address implicit bias. March 6, 2024

The State of the Science on Safe Medication Administration. April 15, 2005

Health Care Quality and Disparities: Lessons from the First National Reports. April 21, 2005

Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. April 13, 2011

First, Do No Harm. September 14, 2011

Symposium on Simulation Science in Health and Medicine. November 24, 2010

ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: updates and critical information 2019. August 14, 2019

Technical Series on Safer Primary Care. January 11, 2017

Patient Safety: An Old and New Issue. August 22, 2007

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Medical Error. January 29, 2014

Assessing the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies in Europe: the MARQuIS project. March 11, 2009

Health and Social Care Ergonomics: Patient Safety in Practice. January 17, 2018

Complications and Errors in Periodontal and Implant Therapy. September 13, 2023

Technology, Education and Safety November 15, 2023

Patient Safety in Dialysis Access. February 25, 2015

Healthcare-Associated Infections. July 22, 2009

Lessons for Work-Life Wellness in Academic Medicine: Parts 1-3. July 26, 2023

Patient Safety and Adverse Events. September 23, 2009

Special Section on Human Factors and Ergonomics in the Operating Room: Contributions That Advance Surgical Practice. June 19, 2019

COVID-19: The Diagnostic Challenge. November 25, 2020

The English Patient Safety Programme. February 10, 2010

Patient Safety in Obstetrics and Gynecology. May 29, 2019

Special Section on Patient Safety and Quality in Healthcare. February 11, 2015

Handoffs: transitions of care for children in the emergency department. January 25, 2017

Perioperative Safety Culture: Principles, Practices, and Pragmatic Approaches. November 1, 2023

Patient Safety Papers 3. April 23, 2008

Patient Safety. January 28, 2015

Quality Improvement in Neurosurgery. April 15, 2015

Innovation in Perioperative Patient Safety. February 27, 2013

Resident Duty Hours Across Borders: An International Perspective. January 21, 2015

Evidence-based Recommendations for Best Practices in Weight Loss Surgery. March 27, 2005

Identification and Prevention of Common Adverse Drug Events in the Intensive Care Unit. June 16, 2010

Perioperative Handoffs. August 2, 2023

The Science of Simulation in Healthcare: Defining and Developing Clinical Expertise. November 19, 2008

Special Issue: Progress at the Intersection of Patient Safety and Medical Liability. December 14, 2016

Proceedings from the European Handover Research Collaborative. December 5, 2012

Language Barriers in Health Care. February 6, 2008

Patient Safety. November 21, 2018

Patient Safety: Committing to Learn and Acting to Improve. January 15, 2014

Themed Issue on the Opioid Epidemic. November 29, 2017

Patient Safety Papers. November 30, 2005

National Cancer Institute–American Society of Clinical Oncology Teams in Cancer Care Project. December 14, 2016

Improving Usability, Safety and Patient Outcomes With Health Information Technology. February 27, 2019

Patient Safety Papers 4. September 2, 2009

AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: 2011. January 25, 2012

Nutrition Support Safety. February 7, 2024

Compliance with central line maintenance bundle and infection rates. August 23, 2023

Patient Safety Innovations

Ambulatory Safety Nets to Reduce Missed and Delayed Diagnoses of Cancer

Preventing falls through patient and family engagement to create customized prevention plans.

The effect of documenting patient weight in kilograms on pediatric medication dosing errors in emergency medical services. May 3, 2023

Annual Perspective

Enhancing Support for Patients’ Social Needs to Reduce Hospital Readmissions and Improve Health Outcomes

The i-readi quality and safety framework: strong communications channels and effective practices to rapidly update and implement clinical protocols during a time of crisis.

Medication errors: the year in review: January through December 2021. January 11, 2023

Free-text computerized provider order entry orders used as workaround for communicating medication information. August 31, 2022

A dynamic risk management approach for reducing harm from invasive bedside procedures performed during residency. September 22, 2021

Encouraging resident adverse event reporting: a qualitative study of suggestions from the front lines. October 30, 2019

ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. December 14, 2016

Avoiding potential harm by improving appropriateness of urinary catheter use in 18 emergency departments. July 16, 2014

ASPEN parenteral nutrition safety consensus recommendations: translation into practice. May 14, 2014

Patient safety, error reduction, and pediatric nurses' perceptions of smart pump technology. May 7, 2014

Are we heeding the warning signs? Examining providers' overrides of computerized drug–drug interaction alerts in primary care. January 22, 2014

Connect With Us

Sign up for Email Updates

To sign up for updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address below.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 Telephone: (301) 427-1364

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Electronic Policies

- HHS Digital Strategy

- HHS Nondiscrimination Notice

- Inspector General

- Plain Writing Act

- Privacy Policy

- Viewers & Players

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- The White House

- Don't have an account? Sign up to PSNet

Submit Your Innovations

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation.

Continue as a Guest

Track and save your innovation

in My Innovations

Edit your innovation as a draft

Continue Logged In

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation. Note that even if you have an account, you can still choose to submit an innovation as a guest.

Continue logged in

New users to the psnet site.

Access to quizzes and start earning

CME, CEU, or Trainee Certification.

Get email alerts when new content

matching your topics of interest

in My Innovations.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.9(4); 2016 Dec

Pregnancy and lactation during long-term total parenteral nutrition: A case report and literature review

Ailsa borbolla foster.

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

Steven Dixon

2 Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

J Tyrrell-Price

3 Bristol Nutrition Biomedical Research Unit, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol UK

Johanna Trinder

There is a paucity of clinical data regarding the management of pregnancy and lactation in women requiring long-term total parenteral nutrition with complex nutritional needs. This case report and literature review highlights common challenges in care and presents evidence which can guide the obstetrician’s approach to care.

Introduction

Knowledge regarding the management of pregnancy during long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is sparse with a recent systematic review identifying only 15 case reports in this setting. 1 TPN and associated underlying medical conditions may be associated with subfertility, miscarriage or patient concerns regarding reproduction, further contributing to a lack of data on this topic.

Case history