Research in Higher Education

- Open to studies using a wide range of methods, with a special interest in advanced quantitative research methods.

- Covers topics such as student access, retention, success, faculty issues, institutional assessment, and higher education policy.

- Encourages submissions from scholars in disciplines outside of higher education.

- Publishes notes of a methodological nature, literature reviews and 'research and practice' studies.

- Aims to inform decision-making in postsecondary education policy and administration.

This is a transformative journal , you may have access to funding.

- William R. Doyle,

- Lauren T. Schudde

Latest issue

Volume 65, Issue 2

Latest articles

Strategically diverse: an intersectional analysis of enrollments at u.s. law schools.

- Nicholas A. Bowman

- Frank Fernandez

- Nicholas R. Stroup

Promoting Age Inclusivity in Higher Education: Campus Practices and Perceptions by Students, Faculty, and Staff

- Susan Krauss Whitbourne

- Lauren Marshall Bowen

- Jeffrey E. Stokes

Unpacking the Gap: Socioeconomic Background and the Stratification of College Applications in the United States

- Wesley Jeffrey

- Benjamin G. Gibbs

Exploring the Interplay Between Equity Groups, Mental Health and Perceived Employability Amongst Students at a Public Australian University

- Chelsea Gill

- Adrian Gepp

Performance-Based Funding and Certificates at Public Four-Year Institutions

- Junghee Choi

Journal updates

Editorial team changes july 2023.

As of July 1, 2023, the Research in Higher Education editorial team has made several transitions

Editorial board changes - 2021

Effective 1 January 2021, the editorial board of Research in Higher Education will undergo several changes.

Editorial board changes 2011

Effective January 1, 2011, several important changes occurred with the journal Research in Higher Education.

Using qualitative research methods in higher education

- Teachers College, Mary Lou Fulton (MLFTC)

- Educational Leadership and Innovation, Division of

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

RESEARCHERS INVESTIGATING ISSUES related to computing in higher education are increasingly using qualitative research methods to conduct their investigations. However, they may have little training or experience in qualitative research. The purpose of this paper is to introduce researchers to the appropriate use of qualitative methods. It begins by describing how qualitative research is defined, key characteristics of qualitative research, and when to consider using these methods. The paper then provides an overview of how to conduct qualitative studies, including steps in planning the research, selecting data collection methods, analyzing data, and reporting research findings. The paper concludes with suggestions for enhancing the quality of qualitative studies.

- applied research

- naturalistic inquiry

- qualitative research

- research methods

ASJC Scopus subject areas

Access to document.

- 10.1007/BF02961475

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Fingerprint

- qualitative method Social Sciences 100%

- research method Social Sciences 92%

- qualitative research Social Sciences 90%

- education Social Sciences 35%

- data collection method Social Sciences 31%

- planning Social Sciences 17%

- experience Social Sciences 8%

T1 - Using qualitative research methods in higher education

AU - Savenye, Wilhelmina

AU - Robinson, Rhonda S.

N2 - RESEARCHERS INVESTIGATING ISSUES related to computing in higher education are increasingly using qualitative research methods to conduct their investigations. However, they may have little training or experience in qualitative research. The purpose of this paper is to introduce researchers to the appropriate use of qualitative methods. It begins by describing how qualitative research is defined, key characteristics of qualitative research, and when to consider using these methods. The paper then provides an overview of how to conduct qualitative studies, including steps in planning the research, selecting data collection methods, analyzing data, and reporting research findings. The paper concludes with suggestions for enhancing the quality of qualitative studies.

AB - RESEARCHERS INVESTIGATING ISSUES related to computing in higher education are increasingly using qualitative research methods to conduct their investigations. However, they may have little training or experience in qualitative research. The purpose of this paper is to introduce researchers to the appropriate use of qualitative methods. It begins by describing how qualitative research is defined, key characteristics of qualitative research, and when to consider using these methods. The paper then provides an overview of how to conduct qualitative studies, including steps in planning the research, selecting data collection methods, analyzing data, and reporting research findings. The paper concludes with suggestions for enhancing the quality of qualitative studies.

KW - applied research

KW - naturalistic inquiry

KW - qualitative research

KW - research methods

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=79953144104&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=79953144104&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1007/BF02961475

DO - 10.1007/BF02961475

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:79953144104

SN - 1042-1726

JO - Journal of Computing in Higher Education

JF - Journal of Computing in Higher Education

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

COVID-19 and Higher Education: A Qualitative Study on Academic Experiences of African International Students in the Midwest

Ifeolu david.

1 School of Health Professions, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO USA

Omoshola Kehinde

2 School of Social Work, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO USA

Gashaye M. Tefera

Kelechi onyeaka.

3 Masters of Public Health Program, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO USA

Idethia Shevon Harvey

4 Health Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO USA

Wilson Majee

5 Health Sciences and Public Health, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO USA

6 Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

COVID-19 pandemic has harshly impacted university students since the outbreak was declared in March 2020. A population impacted the most was international college students due to limited social networks, restrictive employment opportunities, and travel limitations. Despite the increased vulnerability, there has been limited research on the experiences of African-born international students during the pandemic. Using an exploratory qualitative design, this study interviewed 15 African-born international students to understand their experiences during the pandemic. Thematic analysis revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic influenced participants’ academic life directly via an abrupt shift to online learning and indirectly through disruptions in an academic work routine, opportunities for networking, and career advancement, resulting in lower academic performance and productivity. These experiences were worsened by other social and regulatory barriers associated with their non-immigrant status. The study findings suggest an increased need for institutional and community support for international students as vulnerable populations during a crisis to promote sustained academic success.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic (Dumas et al., 2020 ). As of February 2022, there have been about 430 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide, including about 6 million deaths (Worldometer, 2022 ). Of this number, over 78 million cases have contracted the virus in the USA, with over 926 thousand deaths (CDC, 2021 ). Preventative behaviors such as regular hand washing, mask-wearing, social distancing, partial or total lockdowns, and stay-at-home orders were implemented worldwide (Caponnetto et al., 2020 ; Dumas et al., 2020 ; Vanderbruggen et al., 2020 ). These preventative and seclusive measures have been linked with irritability, anxiety, fear, sadness, anger, and boredom, especially among college students (Ornell et al., 2020 ; Sokolovsky et al., 2021 ).

In 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic started, the USA was home to 1,075,496 international students (Schwartz, 2020 ). College students have been impacted by the pandemic in different areas, including mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, loneliness, anger, fear (Dumas et al., 2020 ; Yehudai et al., 2020 ), and a negative impact on their education as well (Yehudai et al., 2020 ). The COVID-19 pandemic changed the educational system, as schools worldwide were forced to cancel in-person classes to help prevent the spread of the virus to students, teachers, and staff (Dumas et al., 2020 ) and the community at large. In the USA, academic institutions transition to online learning from mid-March 2020 until the Fall semester of 2021 (Gutterer, 2020 ). While there has been a slow return to face-to-face learning, many universities and colleges have expanded their online courses to provide virtual learning (Fox et al., 2021 ). In addition, traveling due to the pandemic continues to be a challenge for international students (Bielecki et al., 2021 ; CDC, 2022 ) due to COVID-19 testing requirements and quarantine mandates and the potential for their study visas to be suspended if they return to their home countries for lengthy periods.

Among the student population, international students have been harshly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic academically, socially, and economically due to their immigration status (Alaklabi et al., 2021 ). Americans received financial support in the form of emergency funds, COVID-reliefs, stimulus checks, and financial relief programs to relieve the economic burden on Americans during the pandemic (Alpert, 2022 ). However, because international students are not considered permanent residents or American citizens, they were exempted from receiving financial support (Sprintax, 2021 ), yet they faced increased vulnerability because they did not have familial and emotional support. As a result, most international students relied on their host institutions for emotional and financial support. Several studies show that, before the pandemic, international students, especially those from low-income countries (e.g., African countries), had been experiencing stressors due to geographical locations and dealing with financial burdens from living abroad (Choudaha, 2017 ; McGill, 2013 ). Given these existing vulnerabilities, school and business shutdowns during the pandemic exacerbated international students’ social and psychological stress and affected their academic performance and sense of self-worth (Dumas et al., 2020 ; Yehudai et al., 2020 ). Studies found that American college students delayed their graduation dates, withdrew from classes, lost their internship opportunities, and changed academic plans during the pandemic (Aucejo et al., 2020 ). Approximately 24% of undergraduates at a medium-size university either delayed graduation or withdrew from classes (Aucejo et al., 2020 ).

These outcomes align with Tinto ( 1987 )’s theory on student departure, which argues that students are at risk of dropping out when they experience three major determinants: academic difficulties, the inability of individuals to meet their educational and occupational goals, and their failure to become or remain incorporated in the intellectual and social life of the institution (Tinto, 1987 ). According to Tinto, for students to thrive and remain in school, they need a balance of academic performance, faculty/staff interactions, extra-curricular activities, and peer-group interactions (Tinto, 1993). In the study, we will use the theory of student departure to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted international students’ livelihood resulting in academic difficulties, loss of scholarships or assistantships, internship placements (Aucejo et al., 2020 ), loss of personal interaction(faculty, staff, or peers), and incorporation with their host academic institutions (recreational facilities) – all of which negatively affected their socio-economic well-being and academic performance. The study’s overarching goal is to explore the academic experiences of African international students during the COVID-19 pandemic and highlight relevant lessons for future crisis response. Given the number of international students attending American universities and colleges, insights from the study can enhance our understanding of international students’ needs during crises at three levels: the individual, institutional, and community. At the individual (i.e., student) level, findings could suggest potential opportunities for support during the public health crisis. At the institutional and community levels, findings may inform practitioners on how universities and communities can partner to reduce the vulnerabilities of international students. Findings can also inform the design of international-student friendly national policies.

Research Design and Setting

This paper uses a qualitative research design to explore the academic experiences of African international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. In-depth interviews were conducted by four research team members using a semi-structured interview guide. The study design was chosen to understand the lived experiences of international college students; a population rarely studied during a disaster. The chosen population represented graduate students enrolled in a research institution at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Creswell & Poth, 2019 ). We uncovered many unspoken realities of international students’ academic life during the pandemic by applying qualitative inquiry. The study took place at a large research institution in the Midwest. There were 1,931 and 1,455 international students registered at the university during the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 academic years, respectively. The enrollment rate continued to drop, mainly because of the COVID-19 pandemic and reached 1,436 during the 2021–2022 academic year (University of Missouri, 2021 ). During the study period, international students representing African countries during the pandemic were Nigeria ( N = 41) and Ghana ( N = 28) (University of Missouri, 2021 ). Interviews were conducted by Zoom during the pandemic between March and June 2021.

Research Team

Members of the research team were international students from African countries, racially similar but diverse in their gender identifications and student classification. These individuals approached this study with scholarly and personal interests in identity and the meaning and significance of international students. In terms of their roles in this study, the first author, a Ph.D. level behavioral scientist conducted most of the individual interviews, while the second, third, and fourth authors; advanced doctoral & master’s level students at the time worked directly with the first author in conducting interviews, analyzing transcripts, and generating themes. The last two authors hold doctoral degrees in public health; one of the authors guided the research design, data collection, and analysis. Both senior authors served as independent auditors. The independent auditors’ role was to 1) guarantee that multiple perspectives of the data were honored and discussed and 2) help ensure that analysts’ assumptions, expectations, and biases did not unduly influence the findings (Hill et al., 1997 , 2005 ).

Participant Recruitment

Using a mix of purposive and snowball sampling (Edmonds & Kennedy, 2016 ), twenty-four African international students expressed interest in participating in the study. The research team contacted their international student networks and student groups to recruit participants, such as the African Graduate Student Professional Group and the university student’s international office. The inclusion criteria included being an African international student, currently enrolled in a graduate program, 18 years and older, and willing to be audio recorded.

The Institutional Review Board approved the study and related activities at the corresponding author’s institution. A semi-structured interview guide was used to obtain detailed descriptions of academic life during the pandemic. The interview questions were developed in three stages. First, the research team explored existing literature on international students’ well-being to familiarize themselves with international students’ academic experiences. Second, data on the impacts of the pandemic on college students were examined, and finally, a consensus was reached on the interview questions. The interview questions included: “How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected you academically?” and “How has COVID-19 affected your career goals, plans, or timelines?”.

Before the start of each interview, participants were oriented about the aim of the study, confidentiality, and data management practices. All participants gave their consent to participate in the study. The interviews were audio-recorded via Zoom. The interviews lasted approximately 45 min (range 40 –70 min). All interviews were transcribed verbatim by four members of the research team.

Twenty-four African international students were recruited; however, 15 African international students participated in the study (i.e., five females and ten males). Most of the participants were Ph.D. students ( N = 11), and the remaining were masters-level graduate students ( N = 4) (see Table Table1). 1 ). Nine students expressed interest in the study but did not participate due to scheduling conflicts.

Participant Demographic information

* Graduate teaching assistant/Graduate research assistant

** Part-time employment

Thematic analysis was used to identify themes and patterns and classify segments of the data under each category (Frost, 2021 ). The research team reviewed the first three transcripts and developed a coding scheme. During the process, members of the research team examined relationships among the initial codes, laid out the potential parent, child, and grand-child codes (Creswell & Poth, 2019 ), discussed and resolved all coding conflicts. Following the development of the coding scheme, four of the authors shared and independently coded the rest of the transcripts using NVivo12 qualitative analysis software. The research team held continuous meetings and virtual engagements to review, define and code the themes, and to finalize the analysis and interpretation. To avoid the risk of overgeneralization in the thematic analysis, attention was focused on producing thorough descriptions and detailed information on each theme. More thorough immersion in the data also helped the research team to develop a good understanding of participants’ experiences and make meaning of the themes (Polit & Beck, 2010 ). Reflexivity and positionality were adopted throughout the research process to minimize the risk of personal beliefs, experiences, and positions that could affect the research findings and conclusions (Palaganas et al., 2017 ). As a research team identified as international students with African origins, they were aware of the potential bias in data interpretation. Hence, the research team remained careful to reduce the impact of their experience, preconceptions, and interests by applying greater sensitivity to the participant’s opinions by presenting thick descriptions and direct quotes (Darawsheh, 2014 ). For example, using multiple researchers during the data collection and analysis (i.e., investigator triangulation) provided various perspectives that were discussed and agreed upon before final coding. Throughout this process, the research team members were able to critically self-reflect on the lived experiences of African international graduate students living in the Midwest USA and how that may have influenced the interpretation of findings (Cooper, 2012 ; Singh, 2013 ).

There were 15 participants, five females (33.3%) and ten males (66.7%), who participated in the study. Almost half of the participants (46.7%) represented early adulthood (23 – 32 years). All participants self-identified as Black, and most of the students were Nigerians (66.7%, n = 10). Most participants (93.3%, n = 14) lived in America for two to five years as Ph.D. students (73.3%, n = 11) and relied on graduate assistantship as their primary source of income (86.7%, n = 13). Most of the participants (80%, n = 12) were on F-1 visas, living off-campus in non-university rental properties (66.7%, n = 10), and single, never married (66.7%, n = 10; See Table Table1 1 .)

The four major themes from the thematic analysis were challenges with pivoting to online learning, diminished academic performance, disruption of academic timelines, and stolen and missed opportunities.

Theme 1: Pivoting to Online Learning

To limit exposure and the spread of COVID-19 on campus, US colleges and universities moved from in-person classes to online. While the rationale and benefits of this decision were obvious, there were many unintended consequences on the part of African international students ranging from unmet individual preferences to difficult or unsupportive learning contexts.

Learning Format, Context, and Productivity- a Gift and a Curse

Students select learning formats (in-person/online, asynchronous/synchronous) based on their abilities and preferences, with some preferring more interactive formats than seclusive. As a result of campus closure, students had to do academic work from home, which represented a considerable change in their day-to-day living. Most students found the pandemic to be a curse as they experienced difficulties in getting academic work done at home. One participant expressed how her life was impacted by the sudden pivoting to online when she preferred in-person lectures:

So, it has been quite difficult for me personally. On a personal level, I prefer to be in class because of my attention span. Virtual classes are also a problem for me because it is quite difficult for me to sit down in front of the computer for long hours. (Nigerian, female Ph.D. student)

Similarly, another male doctoral student discussed how pivoting to online learning was disruptive – creating enormous challenges for him to complete his research due to the mandatory “stay-at-home” orders.

I guess it [ COVID-19 ] also kind of affected my research because I was trying to get some articles out. Usually, I like going to the office as a routine just to write and come back home because staying home writing can be a problem. (Nigerian male Ph.D. student)

Working from home presents challenges related to workspace, technology, internet availability (i.e., connectivity), and familial responsibilities. For international students, working from home create challenges as they may be tempted to engage in family discussions during study hours. This challenge is common because of time zone differences with their home countries. Similarly, another Ghanaian doctoral student stated that phone calls from family members were a significant source of distraction, “ I have been turning in work late. Sometimes about only one hour or 30 min before the deadline because I have to talk on the phone ( with family members ), and it is mostly helping other people with situations.”

A Nigerian student, referring to the boredom that resulted from the shelter-in-place mandate, remarked, “sometimes I just get tired of being at home” (Nigerian male master-level ), while a Ghanaian female doctoral student experienced difficulties because of her childcare roles interfering with her coursework. She expressed her challenges working on her dissertation while balancing childcare duties,

I just completed my comprehensive exams during the lockdown. I was done with all my classes, and I was doing my dissertation. I did all my defense, and I did my comprehensive exam defense on zoom. I could not do much during the day because my son was also homeschooling online, and I have to monitor him. Every now and then, he needed help with things, so I could not work during the day. At night when everyone else sleeps, I get to work. It kind of slowed me down.

Switching from campus to a home-learning environment impacted student productivity. Most graduate students described how their inability to access workspaces on campus made it difficult to complete their assignments or research. For example, a master-level Nigerian female student stated that “my productivity was low” and “my productivity dropped significantly at some point.” Similarly, a female Cameroonian doctoral student described her experiences with online learning and how it reduced her productivity:

The fact that I had to stay online zooming for about two and a half hours and more every day was a huge stress for me. So, sometimes, apart from the online class, I still have to read articles online, looking at the computer and all, and that brought with it a lot of mental stress for me. And at a point, I felt like I was not very productive.

A female Nigerian doctoral student expressed similar concerns and detailed her challenges with productivity during ‘stay-at-home’ orders:

My area of study, which was library, was kind of closed, and I had my routine already before the pandemic. Eventually, I was not really motivated to work from home, even though I really wanted to be productive, but it has been a little bit more difficult for me to produce anything academically, that is for sure.

However, some other students found the pandemic to be a gift . For such students, the transition to virtual learning provided added familial benefits such as the flexibility to learn from home while fulfilling other familial duties (i.e., cooking and childcare). A master-level female student from Nigeria who is the primary caregiver of her two school-aged children stated.

Initially, it was good. Somehow, I think it has been good. I can always attend classes online. I appreciate the fact that as a mom, I can easily join classes even when I am late. It has really helped my 8 am classes. I can listen and participate more. The fact that I do not have to skip classes or overly stress myself to go to class in person. I prefer the online option.

Asynchronous courses allowed students to set their schedules to engage in course content and provided the opportunity for them to take care of their familial responsibilities during the pandemic. Further, students who were supported with the resources they needed to sustain productivity tended to be more productive. A master-level male Nigerian student studying computer science was able to use his work laptop at home. He stated how pleased he was with his productivity during the pandemic.

It has been very good for me. I have been more productive than ever. I mean, I wake up in the morning, I can do some work any time. I do not have to worry about the time being too early.

Lack of Social Interactions

Social interaction is a powerful vehicle in learning and can aid individuals with organizing thoughts and filling gaps in their reasoning. The participants missed the social interaction aspect of learning and thus shaping the participants’ academic experience during the pandemic. A male Ivorian doctoral student described difficulties in reaching out for assistance (from peers/professors) during the pandemic, unlike pre-pandemic era when it was easy to walk into offices:

I have had to do a lot of that recently ( referring to sending emails), which I just do not like. So many times, some things I am supposed to do stall. Because I have to psych myself to write that email or write several emails to several people, some of them could be very long. I hate that part of the pandemic because you cannot walk into the office.

Another Nigerian male doctoral student reported difficulties in collaborating with other students online and cited an instance when he had a terrible experience with a group project:

My academics was affected with respect to collaborations. I had difficulties with projects because you are in a virtual class and you don’t know your classmates and you are asked to form groups to work on projects……For research, I’ve had to adapt to communicating with people online as compared to moving around to meet someone in the lab when I’m stuck. Now I have to send emails or send messages on the chat and wait till whenever they respond. So sometimes, getting feedback during research has been slowed down.

Other participants expressed disappointment in having to go through academic work alone. For them, the human interaction with professors and other students was an integral part of the learning process, without which the learning experience was not as fulfilling as they had hoped.

I missed that in-person interaction with people. Also, I feel the professors are not able to gauge when you are not really doing well. It takes people away and you may not really know how well they are doing. (Female Nigerian Master’s student) I just miss being in class. I guess I have been missing a lot, I miss class and I miss interacting with other students. (Male Zimbabwean Ph.D. student)

Theme 2: Diminished Academic Performance

The study participants reported diminished academic performance and outcomes. Much of this experience was linked with struggles to keep up with schoolwork as the pandemic progressed, mainly because the pivot to online learning, which was thought to be short-term, turned out to be prolonged. The extended period under the pandemic exacerbated the challenges international students were dealing with and these struggles manifested in students’ academic performance. A female Nigerian doctoral student explained,

I must say that there has been a change in terms of my preparedness since COVD; I have been studying less and having difficulties getting assignments done on time. Overall, I have not been learning; rather, I have just been trying to keep up with schoolwork.

Another female Ghanian doctoral student who had similar experiences and needed extension for some of her papers narrated,

I have called for an extension. When my son’s school called me to pick him up due to another child being infected with the virus. I also had to deal with the death of a loved one during that time. Though COVID-19 may not have been a direct cause, they all piece together or played a role.

She believed that the pandemic indirectly affected her academics due to the added commitments and emotions associated with events during the outbreak, such as childcare, bereavement, and emotions.

Lack of motivation was also cited as a common challenge associated with schoolwork during the pandemic. Most students reported significantly limited academic productivity due to diminishing motivation and procrastination. “ When the COVID-19 first started, you tend to postpone procrastinate a lot, so you lose sight of being in an academic environment .” (Male Nigerian, Ph.D. student) because “ Being at home like all day long, makes you feel like, well I have time, you know so I was less motivated and less organized.” (Male Nigerian, Masters student ) . Another male Ghanian doctoral student elaborated,

I have been procrastinating a lot. And I am in a tight corner. My final project is going to be due soon, and I am still with another paper that I need to write. It is hard to just sit down, manage my time, and get as much done. Just doing 30 minutes of my work sometimes is a big accomplishment. Procrastination has been a big issue for me.

Theme 3: Disruption of Academic Timelines

Disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic response influenced some aspects of progression and timelines for some participants, especially those pursuing doctoral programs. While academic milestones such as presentations, publications, internships, and comprehensive exams were difficult to achieve given diminished productivity, research activities requiring human/laboratory interactions also stalled. A male Nigerian doctoral student detailed his frustration with disrupted research activities and how that affected his academic progression:

Before the pandemic, my plan was to graduate last year, but the data analysis, publication, and writing got pushed back. We could not have access to the lab, and months were lost. So, I lost about eight months, and I could not graduate at the expected time

Another male Ivorian doctoral student explains how his research activities had slowed down due to communication challenges created by COVID-19-related shutdowns,

You know, when you are stuck on something, you just move to the person sitting down in the lab, but now you have to send emails or send messages on the chat and wait till whenever they respond. So sometimes, you are not getting any feedback which slowed my research.

Echoing the same feelings, another male Nigerian Ph.D. student lamented over lost time, “So instead of four years, it’s looking like it’s going to four and a half now or five years.” For international students, staying on track with their studies is critical as their stay in the USA is determined by various external factors such as the type of visa, sponsor requirements, and their ability to secure employment post-graduation.

Theme 4: Stolen and Missed Opportunities

While participants found the courage to adapt to the changes in academic routine, they were discouraged by the pandemic’s influence on networking and career advancement opportunities, an essential aspect of the international student experience in the USA. Due to social distancing regulations, conferences and college events were canceled or pivoted to virtual. In-person conference participation provides opportunities for students to connect with other students and faculty from various institutions and serves as a platform for sharing and receiving feedback on research projects. A female Nigerian doctoral student described her disappointment as follows, “I had submitted an abstract to a university in China and so we were waiting to go for the conference you know. So, I was going to travel to China for the presentation. But the conference was canceled” Another participant with similar regrets for settling for a virtual event said, “It does affect my conference travel plans, most of my conferences, I had to do virtually” (Female Cameroonian Ph.D. student).

During the pandemic, internship opportunities were limited as many organizations had to shut down or make modifications to offer virtual internships. Unsurprisingly, participants lamented missing internship opportunities, and for some, this had far-reaching implications on their academic timelines and student visa status. A male Nigerian Ph.D. student noted,

I did not have many options for internships because many companies canceled their internship programs. There were one or two companies I was hopeful for: I did not just hear anything from them anymore. So, I had to postpone my internship plans to this year. I have actually secured an internship, and after discussing with my advisor, it is more like, okay it might lead to like one extra year you know.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic created shortages of internship opportunities, screening for the few available internships became extremely competitive as employers preferred USA citizens or green card holders over international students on other visas, as stated by one participant: “you know because most jobs are now asking for either a citizenship or a green card holder. So, it makes it really tough.” (Female Cameroonian doctoral student).

This exploratory study examined the academic experiences of international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main findings highlight the range of academic vulnerability among African international students during the pandemic. Pivoting to online learning and its associated disruptions exposed an already vulnerable population to more challenges – amendments to academic timelines, reduced academic productivity, and the inability to participate in practical training opportunities such as internships and conference presentations.

While higher education was no exception to the disruptive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, international students in USA universities may have been hit the hardest mainly because of a lack of institutional support for a population that has many other disaster risk factors associated with being immigrant students, such as lack of native social network, inability to travel (due to visa regulations and bans imposed to control the spread of the virus), employment restrictive visas/inability to work off-campus, lack of access to recreational resources outside campus, and poor home access to Wi-fi. Because campus closures and the transition to exclusive online learning were abrupt, many college students struggled to adapt to the new way of learning. The study participants mentioned struggles in keeping up with academic work due to a lack of motivation and limited access to help from tutors and fellow students in the absence of human interaction. This finding supports the emerging literature on COVID-19 experiences of college students. In a study conducted among 257 college students in a mid-sized university in the northeast USA, interpersonal disengagement and struggles with motivation were significant issues reported by the participants during the COVID-19 pandemic (Tasso et al., 2021 ). In the same vein, participants reported difficulties participating in and completing online group projects due to virtual communication challenges associated with using email, GroupMe, Zoom, and other online communication channels that lack interpersonal engagement. This supports findings from an Indonesian study where 301 dentistry students asked to evaluate their experiences with online versus in-person classes reported a preference for in-person over online learning (Amir et al., 2020 ). Amir et al. ( 2020 ) found that most students disliked online classes, and 60% thought communication was more difficult with online learning and resulted in less learning satisfaction (Amir et al., 2020 ). Another study among Ghanaian students revealed similar attitudes towards online learning (Aboagye et al., 2020 ). Our findings also resonate with Tinto’s ( 1987 ) hypothesis that perceived academic difficulties could endanger student retention in higher education. In addition to communication challenges, participants in our study further identified the inability to separate schoolwork from their “at home” activities as a recipe for exhaustion and fatigue that contributed to decreased academic productivity. Learning from home meant that student homes became classes and study rooms.

This study supports Meeter et al. ( 2020 ) findings that students had challenges with academic structure and planning because it was hard to separate work and leisure time (Meeter et al., 2020 ). Further, students who relied on on-campus spaces like offices and libraries were more significantly affected because they had to quickly make drastic changes to their home routines. The lack of change in the environment created a monotonous routine of long screen and computer time, resulting in a lack of motivation for intellectual creativity and productivity.

On a peculiar note, participants highlighted how existing vulnerabilities associated with limited social networks within their communities and with family members in their own countries shaped their academic experiences during the pandemic. Similar research found that female students experienced more vulnerabilities (Hagedorn et al., 2021 ; Ipe et al., 2021 ; Staniscuaski et al., 2021 ) due to African gender roles that place the responsibilities of cooking, cleaning, and childcare on women, insights gleaned from our study suggest that female students were burdened with these extra responsibilities. Thus, international female students with research projects or teaching assistant positions had to extensively stretch their capabilities to meet home demands. Although some participants were able to turn this change into opportunities, and a few reported minimal challenges with the transition based on the support from their school departments, the lifestyle change still took some time to adapt to, especially in the absence of familial support.

The study participants also reported delays in academic timelines and milestones. This was primarily due to the inability to conduct research work during the pandemic or challenges in coping with the drastic changes in academic demands. Studies among college students in the US found that delayed graduation dates, withdrawal from classes, and changes in academic plans occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aucejo et al., 2020 ). Approximately 24% of undergraduates at the Arizona State University had either delayed graduation or withdrawn from classes by the end of the spring 2020 semester. Another study among college graduate and undergraduate students in the Appalachia Region reported reduced productivity and missed academic milestones, affecting graduation timelines (Hagedorn et al., 2021 ). The distribution of this experience was also markedly disproportionate, with lower-income students being affected the most (Aucejo et al., 2020 ). International students have minimal financial opportunities, given visa employment restrictions and exclusion from federal COVID-19 financial support. While COVID-19 prevention policies during the pandemic may have intensified the distribution of these academic experiences, researchers fear that the implications of these events could impact international student retention, as predicted by Tinto ( 1987 ).

As with many college students in the USA, the participants expressed disappointment regarding missed opportunities for internships and networking during the pandemic. While more research is needed to quantify the density of this problem among international students, literature among USA undergraduates indicates that 13% of the population reporting loss of internship positions or job offers rescinded during this time (Aucejo et al., 2020 ). With networking being a significant part of the international student academic and cultural experience in the USA, canceling conferences and other academic networking platforms represents tremendous lost opportunities. Some of our study participants had difficulties securing internship positions due to the pandemic, and because this was a major milestone in some academic programs, the resulting delayed graduation timeline is palpable. Hagedorn et al. ( 2021 ) had similar findings when students from their study reportedly missed internship positions required for graduation due to the pandemic. Although the experience is like that of other students in the USA, participants from this study specifically expressed concerns about being less likely to secure an internship position during the pandemic due to the competition for limited internship spots and the fact that some positions specifically exclude international student applicants in their eligibility criteria.

The COVID-19 pandemic influenced the participants’ academic life directly via the shift to online learning and indirectly through disruptions in career advancement and networking opportunities. As international students, their experiences were worsened by other social and regulatory barriers associated with studying in a foreign country. Therefore, more attention needs to be focused on international students as vulnerable populations in higher education.

Implications for Practice

Insights from this study revealed a need for institutional support for international students during pandemics. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the resultant campus closures, and the transition to online learning highlighted pandemic-related vulnerabilities among African international students. These vulnerabilities call for institutional support for international students during crises to ensure their academic success and for the USA to continue to enjoy the economic, social, and cultural benefits international students bring to the economy. In line with Tinto’s (1975) theory, there is a need to minimize academic challenges international students experience, support social integration, and provide adequate institutional support (i.e., financial, technical, and emotional) during the pandemic to create diverse and inclusive learning environments in which all students feel supported to do their best. Universities can establish student-serving disaster preparedness committees that could relate to and ensure that the needs of international students are met. The federal government can also formulate immigrant visa policies that allow flexibility for international students to secure employment outside their universities during crises such as COVID-19. The study findings also suggest a need for quantitative research focused on the experiences of international students during the pandemic to figure out the density and possible mitigation opportunities for the challenges faced by these vulnerable groups of students.

Limitations

Due to the qualitative nature of our study and the limited sample size, our findings may not be generalizable to other international students. Additionally, the study participants constituted students who have been living in the USA for more than two years; thus, their experiences could differ from newly enrolled international students who are likely to have even weaker support systems while struggling with cultural adaptation. Findings should be interpreted with caution because of the lack of gender diversity among the participants. The sample consisted of cisgender participants, and the ratio included more male students than female students (i.e., a 2:1 male to female ratio). Future studies should include the experiences of more African international female students and students who self-identify as transgender or non-binary gender. Including multiple sexual identities would have enriched the study findings as these populations remain understudied. We strongly believe that this study contributes to the emerging knowledge on the academic challenges faced by African international students during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The research team made every effort to maintain rigor and trustworthiness by applying principles of immersion, thoroughness, and reflexivity (Creswell & Poth, 2019 ). Future studies should include a more diverse and representative sample of African international students by educational levels (undergraduates), gender (i.e., female, transgender, and non-binary gender), and sponsorship type (scholarship, assistantship, and out-of-pocket funded students). Future studies should also explore the role of demographics and culture in shaping the experiences of international students.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fellow students for their participation in this study.

Declarations

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Aboagye, E., Yawson, J. A., & Appiah, K. N. (2020). COVID-19 and E-learning: the challenges of students in tertiary institutions. Social Education Research , 1–8. 10.37256/ser.212021422

- Alaklabi M, Alaklabi J, Almuhlafi A. Impacts of COVID-19 on International Students in the US. Higher Education Studies. 2021; 11 (3):37–42. doi: 10.5539/hes.v11n3p37. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alpert, G. (2022). A breakdown of the fiscal and monetary responses to the pandemic . Retrieved February 18 from https://www.investopedia.com/government-stimulus-efforts-to-fight-the-covid-19-crisis-4799723

- Amir, L. R., Tanti, I., Maharani, D. A., Wimardhani, Y. S., Julia, V., Sulijaya, B., & Puspitawati, R. (2020). Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Medical Education , 20 (1). 10.1186/s12909-020-02312-0 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Aucejo EM, French J, Ugalde Araya MP, Zafar B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Journal of Public Economics. 2020; 191 :104271. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bielecki M, Patel D, Hinkelbein J, Komorowski M, Kester J, Ebrahim S, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Memish ZA, Schlagenhauf P. Air travel and COVID-19 prevention in the pandemic and peri-pandemic period: A narrative review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021; 39 :101915. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101915. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caponnetto, P., Inguscio, L., Saitta, C., Maglia, M., Benfatto, F., & Polosa, R. (2020). Smoking behavior and psychological dynamics during COVID-19 social distancing and stay-at-home policies: A survey. Health Psychology Research , 8 (1). 10.4081/hpr.2020.9124 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- CDC (2021). CDC COVID-19 data tracker . Retrieved April 12 from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days

- CDC (2022). Domestic travel during COVID-19 information. Retrieved January 12 from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/travel-during-covid19.html

- Choudaha R. Three waves of international student mobility (1999–2020) Studies in Higher Education. 2017; 42 (5):825–832. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1293872. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper, H. M. (2012). APA handbook of research methods in psychology. Vol. 1, Foundations, planning, measures, and psychometrics . American Psychological Association. 10.1037/13619-000

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2019). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches . SAGE Publication Incorporated.

- Darawsheh W. Reflexivity in research: Promoting rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2014; 21 (12):560–568. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2014.21.12.560. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM. What Does Adolescent Substance Use Look Like During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Examining Changes in Frequency, Social Contexts, and Pandemic-Related Predictors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020; 67 (3):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmonds, W. A., & Kennedy, T. D. (2016). An applied guide to research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods . Sage Publications.

- Fox MD, Bailey DC, Seamon MD, Miranda ML. Response to a COVID-19 Outbreak on a University Campus — Indiana, August 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021; 70 (4):118–122. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a3. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frost, N. (2021). Qualitative research methods in psychology: Combining core approaches 2e . McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Gutterer, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on international students perceptions . Retrieved April 2 from https://studyportals.com/intelligence/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-international-students-perceptions/

- Hagedorn RL, Wattick RA, Olfert MD. “My Entire World Stopped”: College Students’ Psychosocial and Academic Frustrations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11482-021-09948-0. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hill, C., Knox, S., Thompson, B., Williams, E., Hess, S., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Education Faculty Research and Publications, 52 . 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

- Hill CE, Thompson BJ, Williams EN. A Guide to Conducting Consensual Qualitative Research. The Counseling Psychologist. 1997; 25 (4):517–572. doi: 10.1177/0011000097254001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ipe TS, Goel R, Howes L, Bakhtary S. The impact of COVID-19 on academic productivity by female physicians and researchers in transfusion medicine. Transfusion. 2021; 61 (6):1690–1693. doi: 10.1111/trf.16306. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McGill J. International Student Migration: Outcomes and Implications. Journal of International Students. 2013; 3 (2):167–181. doi: 10.32674/jis.v3i2.509. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meeter, M., Bele, T., den Hartogh, C., Bakker, T., de Vries, R. E., & Plak, S. (2020). College students’ motivation and study results after COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. 10.31234/osf.io/kn6v9

- Ornell F, Moura HF, Scherer JN, Pechansky F, Kessler FHP, Von Diemen L. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 289 :113096. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113096. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Palaganas, E. C., Sanchez, M. C., Molintas, V. P., & Caricativo, R. D. (2017). Reflexivity in qualitative research: A journey of learning. Qualitative Report , 22 (2). 10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2552

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010; 47 (11):1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz, N. (2020). Number of international students in US declines for first time in over a decade. HigherEdDive.com . https://www.highereddive.com/news/number-of-international-students-in-us-declines-for-first-time-in-over-a-de/589032/

- Singh J. Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2013; 4 (1):76–77. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.107697. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sokolovsky AW, Hertel AW, Micalizzi L, White HR, Hayes KL, Jackson KM. Preliminary impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on smoking and vaping in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2021; 115 :106783. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106783. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sprintax. (2021). Nonresident aliens: Your guide to navigating the COVID-19 CARES Act Stimulus Payments . Retrieved February 18 from https://blog.sprintax.com/nonresident-aliens-guide-navigating-covid-19-cares-act-stimulus-payments/#:~:text=No.,a%20dependent%20by%20another%20taxpayer

- Staniscuaski F, Kmetzsch L, Soletti RC, Reichert F, Zandonà E, Ludwig ZMC, Lima EF, Neumann A, Schwartz IVD, Mello-Carpes PB, Tamajusuku ASK, Werneck FP, Ricachenevsky FK, Infanger C, Seixas A, Staats CC, de Oliveira L. Gender, Race and Parenthood Impact Academic Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: From Survey to Action. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 12 :663252–663252. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663252. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tasso, A. F., Hisli Sahin, N., & San Roman, G. J. (2021). COVID-19 disruption on college students: Academic and socioemotional implications . Educational Publishing Foundation. 10.1037/tra0000996 [ PubMed ]

- Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition . ERIC.

- University of Missouri. (2021). Fast facts 2021: International students . Retrieved February 18 from https://international.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/open-doors-mizzou_fast-facts-2021.pdf

- Vanderbruggen N, Matthys F, Van Laere S, Zeeuws D, Santermans L, Van Den Ameele S, Crunelle CL. Self-Reported Alcohol, Tobacco, and Cannabis Use during COVID-19 Lockdown Measures: Results from a Web-Based Survey. European Addiction Research. 2020; 26 (6):309–315. doi: 10.1159/000510822. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Worldometer. (2022). Coronavirus cases . Retrieved February 23 from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- Yehudai M, Bender S, Gritsenko V, Konstantinov V, Reznik A, Isralowitz R. COVID-19 Fear, Mental Health, and Substance Misuse Conditions Among University Social Work Students in Israel and Russia. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00360-7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- English Norsk

Qualitative Research in (Higher) Education (DUH240)

The course is offered partially on web-based platforms in the form of a hybrid course (online+F2F), and we will primarily use Canvas as the course management system. Course materials (e.g., syllabus, weekly readings, and announcements ) will be available on the Canvas site, which will provide interaction and discussion opportunities. The Canvas site is also an important medium for accessing course updates and announcements.

Course description for study year 2023-2024. Please note that changes may occur.

Course code

Credits (ects), semester tution start.

Spring, Autumn

Number of semesters

Exam semester, language of instruction.

The course introduces PhD students to qualitative research methodology and aims to promote knowledge of qualitative research to generate in-depth inquiry in the field of (higher) education. The course also emphasises relevant theories, methods, and qualitative research practices to develop knowledge, skills and competence to engage in planning, conducting and writing up qualitative inquiry.

The course requires critical reading of suggested resources to prepare for in-depth theoretical discussions about qualitative research, qualitative research topics, qualitative designs, data collection strategies, and approaches to data analysis. To this end, the students identify and elaborate on different approaches within qualitative designs and develop qualitative research skills described in the course content through step-by-step, hands-on, and interactive activities. The course will also help develop individual and collaborative qualitative research skills, thus enhancing the ability to create practical as well as theoretical knowledge.

The following broad questions will guide the course:

1. What is qualitative research, and why is it important?

2. How are qualitative research methods chosen and employed?

3. What types of questions initiate qualitative research studies in (higher) education?

4. What are the preliminary assumptions that guide qualitative research in general, and in (higher) education in particular?

5. What are the different types of approaches and methods?

6. What are the analytic techniques used by qualitative researchers?

7. What are some methods and frameworks of discussion?

8. How do qualitative researchers write up and disseminate research?

Course Expectations and Requirements:

- Graduate level performance is expected from all students. At this level, it is assumed that students are, to a great extent, responsible for their own learning. Therefore, the relevant assignments are to be fully and carefully completed PRIOR to the class.

- Class attendance and quality in-class participation is expected.

- Students should complete all assignments on time. All out-of-class assignments should be typewritten, unless otherwise stated. Late submissions will not be accepted.

- Students need to manage their own learning to ensure coverage of the syllabus.

- Students are strongly encouraged to seek regular feedback about their study through face-to-face or online tutorials.

Academic Honesty:

Plagiarism: Students who take this class are urged to avoid plagiarism, i.e., intentionally presenting words, ideas or work of others as your own work. Plagiarism includes copying others’ ? homework, using a portion of or a complete work written or created by another without crediting the source, using your own work completed in a previous class for credit in another class without permission, paraphrasing another’s work without giving credit, and using others’ ideas without giving credit.

Remember: Making references to the work of others strengthens your own work by granting you greater authority and by showing your participation discussion located within an intellectual community. When you make references to the ideas of others, it is essential to provide proper attribution and citation. Failing to do so is considered academically dishonest, as is unacknowledged copying or paraphrasing someone else’s work. The consequences of such behaviour will lead to consequences ranging from failure on an assignment or the course to dismissal from the university. Please ask if you are in doubt about the use of a citation. Genuine misunderstandings can always be prevented or corrected.

The course is taught in English.

Learning outcome

By the end of the course, the student will be able to:

- understand the major approaches to qualitative research in education

- analyse fundamental theories that underline research paradigms

- explain the principles underlying the use of qualitative research methods

- justify qualitative research processes in terms of robustness and rigor

- identify and design research topics for a detailed examination of phenomena

- develop research questions through qualitative methods.

- engage in procedures regarding design, participants, and context

- collect and analyze data from various and multiple methods

- synthesize and integrate multiple data sources

- write up an individual or collaborative qualitative report

- plan, conduct, and evaluate qualitative research as professional development

- develop an understanding of key terms and contemporary issues in qualitative research in (higher) education (e.g., reflexivity, voice, authority, representation, credibility, trustworthiness and ethics.

- develop a critical lens through which to address educational issues

- induce data-driven interpretations to inform educational practices

- gain insights into the challenges of qualitative research

Required prerequisite knowledge

The final evaluation consists of a 20 minute oral exam, online or face-to-face. The exam starts with a 10 min verbal presentation of a self-chosen qualitative research design using a particular approach which includes thick description of context, participants, data collection and analysis as well as validity issues, and proceeds with a collegial discussion about the project. The exam is assessed (pass/fail) with constructive feedback.

Coursework requirements

Course teacher(s), course coordinator:, method of work.

The course is offered partially on CANVAS platform in the form of a hybrid course (online+F2F). Course materials (e.g., syllabus, weekly readings, and announcements) is available on the CANVAS site, which also provides opportunities for communication - access to course content, updates, and announcements as well as submission of the given assignments.

The course consists of lectures led by course tutors and seminars based also on student-led discussions. A detailed timetable and syllabus is made available to the course participants at the beginning of the semester.

Course assessment

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, developing a community of inquiry using an educational blog in higher education from the perspective of bangladesh.

- 1 Institute of Education and Research (IER), University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2 School of Education and Social Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, United Kingdom

Web 2.0 tools such as blogs, wikis, social networking, and podcasting have received attention in educational research over the last decade. Blogs enable students to reflect their learning experiences, disseminate ideas, and participate in analytical thinking. The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework has been widely used in educational research to understand and enhance online and blended learning platforms. There is insufficient research evidence to demonstrate the impact of educational blogging using the CoI model as a framework. This article explores how blogs can be used to support collaborative learning and how such an interaction upholds CoI through enhancing critical thinking and meaningful learning in the context of higher education (HE). An exploratory sequential mixed-method approach has been followed in this study. A convenience sampling method was employed to choose 75 undergraduate students from Dhaka University for a 24-week blogging project. Every publication on the blog was segmented into meaningful units. Whole texts of posts and comments are extracted from the blog, and the transcripts are analyzed in a qualitative manner considering the CoI framework, more specifically, through the lens of cognitive, social, and teaching presence. In addition, the semi-structured questionnaire is used to collect data from students irrespective of whether blogging expedited students' learning or not. The research findings indicate that cognitive presence, namely, the exploration component, is dominant in blog-based learning activity. Moreover, this research has demonstrated that blogs build reliable virtual connections among students through exchanging ideas and information and by offering opportunities for reflective practice and asynchronous feedback. This study also revealed challenges related to blogging in the context of developing countries, including lack of familiarity with blogs, restricted internet connectivity, limited access to devices, and low levels of social interaction. It is recommended that different stakeholders including policymakers, curriculum developers, and teachers take the initiative to synchronize the utilization of educational blogs with the formal curriculum, guaranteeing that blog activities supplement and improve traditional teaching–learning activities.

1 Introduction

The prevalence of online learning is rapidly expanding and has become more advanced due to ongoing technological improvements ( Seaman et al., 2018 ). Web 2.0 tools, such as blogs, wikis, social networking, media sharing, and podcasting, allow for self-directed, collaborative, and widespread learning by sharing resources, regardless of physical or geographical constraints ( Song and Bonk, 2016 ). For instance, blogs can be used in online and blended learning platforms to foster students' reflective learning ( Milad, 2017 ), developing learning communities through several strategies like posting students' work, exchanging hyperlinks, and so on ( Kerawalla et al., 2009 ). In this connection, several researchers added that blogging has obvious advantages to form the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework and to trigger meaningful learning through improving the social, cognitive, and teaching presence ( Cameron and Anderson, 2006 ; Petit et al., 2023 ). In addition, effective instructional strategies and facilitation of discourse guided by teachers are more significant in creating CoI than any other approach ( Garrison and Akyol, 2013 ). Additionally, Jimoyiannis et al. (2012) argued that properly designed blog activities can help students achieve higher cognitive levels by enhancing their communication and collaboration skills and their critical thinking. However, despite the widespread excitement and curiosity around the learning design framework and online learning environments, there is a lack of research on the educational influence of learning designs ( Bower, 2017 ). Shifting to the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread adoption of online learning, the pandemic has initiated a radical and rapid rethinking of the teaching–learning arrangement. The challenge was to provide guidance and support to educators to shift their curriculum to an online environment ( Garrison, 2020 ). The CoI framework may provide a coherent representation of relevant information and the means to navigate between theoretical and practical sources of information ( Garrison, 2020 ). Hence, it is vital to examine how CoI inquiry could be designed and implemented in online environments. Additionally, there is a lack of research evidence to demonstrate the impact of educational blogging when using the CoI model as a framework. Moreover, no research article on the use of educational blogs for a higher education level in Bangladesh has been found yet. The study aims to investigate the potential of the blogging environment in assisting higher education students in their learning process, focusing on key elements of the CoI framework. Hence, the following research questions will be addressed:

i. What is the nature of the students' interaction in the educational blogging practice?

ii. How does participating in blog-based learning activity support students' learning experience?

iii. What problems do the students confront while engaging in educational blogging?

2 Literature review

Blogs can be characterized as a web-based archive displaying contents in reverse chronological entry date. People with little technical knowledge can publish as well as share their thoughts, opinions, and emotions with others using blogs ( Pifarré et al., 2014 ). The use of blogging technologies by students in educational settings is on the rise globally ( Ifinedo, 2017 ). Blogs are commonly advocated as collaborative tools that facilitate active learning among students ( Jimoyiannis and Angelaina, 2012 ). However, the rate of users' participation can diverge from session to session and blog to blog ( Lawrence et al., 2010 ). Blogs can create an online collaborative portfolio for course-related resources, assignments, calendars, events, teaching experiences, open discussions, students' queries, and so on ( Kaya et al., 2012 ). Hence, blogs can play a vital role in establishing the learning community as well as encouraging interpersonal communication among teachers and students of higher education ( Kaçar, 2021 ).

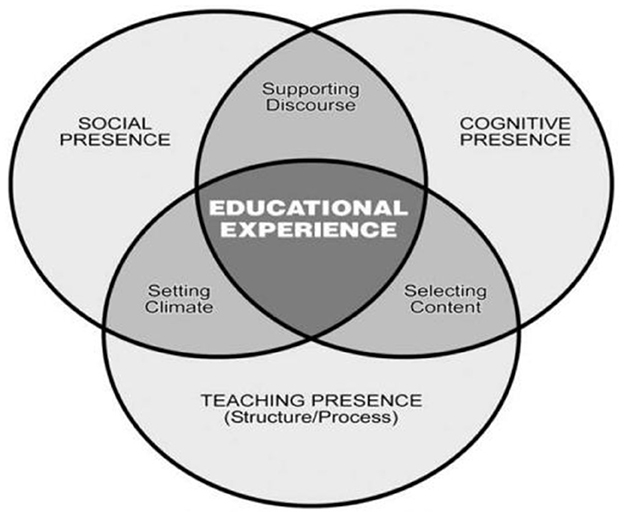

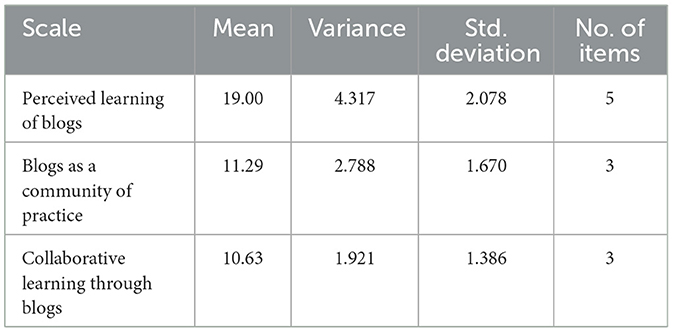

The analysis of the educational use of blogs often involves various methods and frameworks to understand the dynamics, engagement, and impact of the blog content ( Kaul et al., 2018 ). The CoI model is a framework that is particularly relevant for analyzing the educational aspects of blog posts, especially in online learning platforms ( Kim and Gurvitch, 2020 ). CoI was initially developed as a conceptual framework to guide the practice of collaborative learning through asynchronous communication in online settings ( Garrison and Akyol, 2013 ; Shea et al., 2022 ). The origin of the CoI model is grounded in Vygotsky's theory of social development ( 1978 ) and Dewey's practical inquiry and critical thinking model ( 1933 ) ( Garrison and Akyol, 2013 ; Shea et al., 2022 ). The structure depicted in Figure 1 illustrates the three primary components (teaching, cognitive, and social presence) of CoI and their intersection, which are crucial for comprehending the dynamics of profound and significant online learning experiences ( Garrison et al., 2010a ). Subsequently, other research studies focused on collating data related to learning design as well as the evaluation process in the online learning experience to the cognitive dimension to identify and measure three constitutional components of the CoI framework, namely, social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence ( Garrison et al., 2010b ; Angeli and Schwartz, 2016 ).

Figure 1 . Community of Inquiry framework [adapted from Akyol and Garrison (2011) ].

Among the three elements of the CoI framework, the role of social presence has been investigated most extensively in online educational settings ( Garrison and Arbaugh, 2007 ). Research has claimed that social presence enhances the learner's satisfaction, while the internet is used as a medium to deliver education ( Cui et al., 2013 ). However, the positive social environments including affective expression, open discussion, and group cohesion lead toward a hidden curriculum of the technological aspects of distance or virtual education ( Moodley et al., 2022 ). In addition, Akyol and Garrison (2011) described cognitive presence as the extent to which learners can construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse. Cognitive presence is considered a distinctive outcome of higher education since long rooted in Dewey's (1933) construction of practical inquiry and critical thinking ( Sadaf et al., 2021 ). Akyol and Garrison (2011) implemented cognitive presence in terms of a practical inquiry model and established a four-phase process including triggering, exploration, integration, and resolution in the context of educational settings. However, Marshall and Kostka (2020) emphasized the importance of teaching presence to ensure effective online learning rather than interactions among participants. Teaching presence has been conceptualized to comprise three components: instructional design and organization, facilitating discourse, and direct instruction. Several pieces of literature ( Chakraborty and Nafukho, 2015 ; Chakraborty, 2017 ; Bhatty, 2020 ) highlight the significance of teaching presence in online learning platforms to meet the needs of students, to ensure perceived learning, and to certify the sense of community.

Researchers were likely intrigued by the potential of blogs to foster a sense of community and social presence, which are essential elements of the CoI framework. The exploration of CoI in educational blogs is likely driven by a combination of theoretical considerations, gaps in current research, and practical implications. The research design was meticulously constructed to explicitly address these qualities and offer significant contributions to the field of online education.

3 Theoretical framework: Community of Inquiry (CoI) in educational blogs

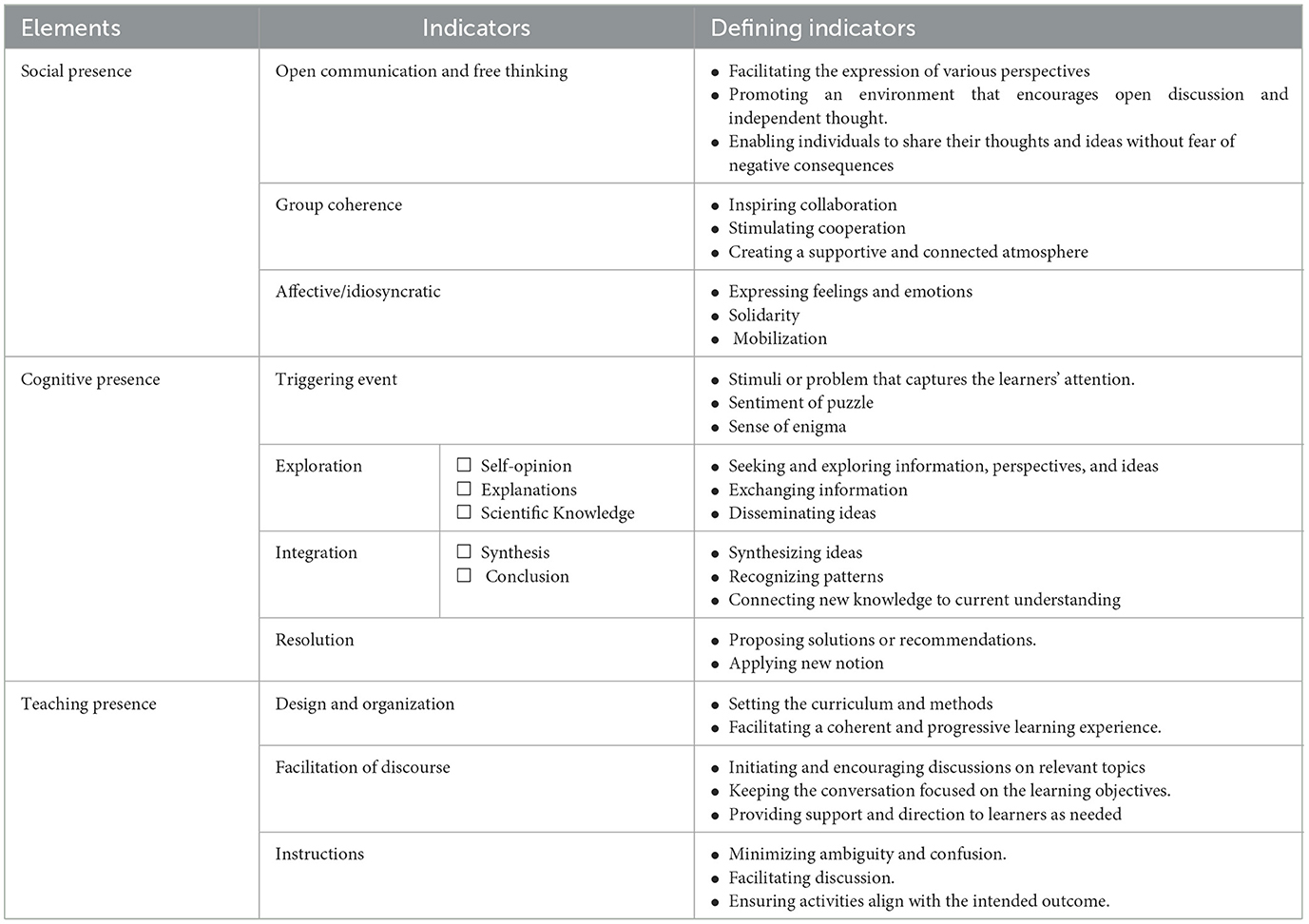

Several researchers ( Pifarré et al., 2014 ; Jimoyiannis and Roussinos, 2017 ) have suggested the design of educational blogging activities applying the CoI model as an analysis framework considering students' engagement and presence. The primary approach underlying the design was to integrate an educational blog with both content space and discussion space. The content space encompasses blog posts, articles, multimedia elements, and other sources of information generated by the author or contributors. On the other hand, the discussion space refers to the section of the blog platform where readers and participants can actively participate in conversations, express opinions, ask questions, and offer feedback about the content presented in the content space. This design confirms the collaborative nature of the blog ( Jimoyiannis and Angelaina, 2012 ). Moreover, the CoI model determines indicators to recognize and measure each presence in an educational blog community. Basic components and indicators of CoI are presented in Table 1 considering educational blogs as a collaborative learning platform.

Table 1 . Indicators to recognize and measure each presence in an educational blog [modified from Garrison and Arbaugh (2007) ].

Table 1 provides a more explicit definition of CoI elements, using both indicators and instances. These characteristics have been employed to unambiguously ascertain social presence, cognitive presence, and instructional presence in a blog-assisted educational context. This mapping has been used in laying the groundwork for this research.

4 Methodology

4.1 research context.

Although technology-mediated learning has been introduced at the higher education level in Bangladesh in recent years ( Chowdhury et al., 2018 ), different online-based technologies have yet to be integrated into the curriculum and assessment process ( Arefin et al., 2023 ). In this study, the educational blog was created using Google Sites considering a project-based learning approach, which combines online and in-person instruction to enhance learning by offering guidance, resources, and feedback. The goal of this blog-based activity was to promote for blogs as additional resources in traditional teaching methods, with a focus on developing engaging and efficient instructional materials that are in line with specific learning objectives. This activity also aimed to foster collaborative learning and effective communication among students. However, there was no correlation between student involvement in the blog-based learning activity and the assessment process. Moreover, the curriculum did not provide any guidance on using alternative online platforms like blogs for instructional activities.

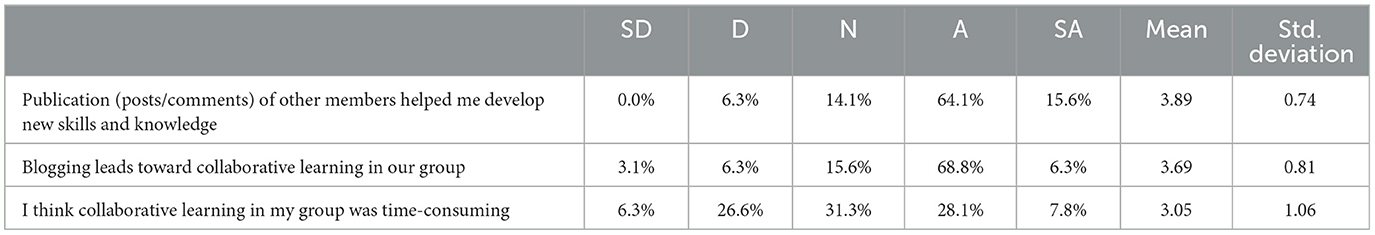

This study employed an exploratory sequential mixed-method approach. A convenience sampling method was employed to choose undergraduate students from Dhaka University for a 24-week blogging project. A total of 75 students enrolled in the “Introduction to Computer Course” of the B.Ed. program were invited to participate in this blog-based activities and were assessed on how collaborative learning opportunities contribute to the achievement of learning outcomes. A total of 65 students actively participated in collaborative blog discussions, contributing by uploading content and/or commenting to promote the discourse and reflection.

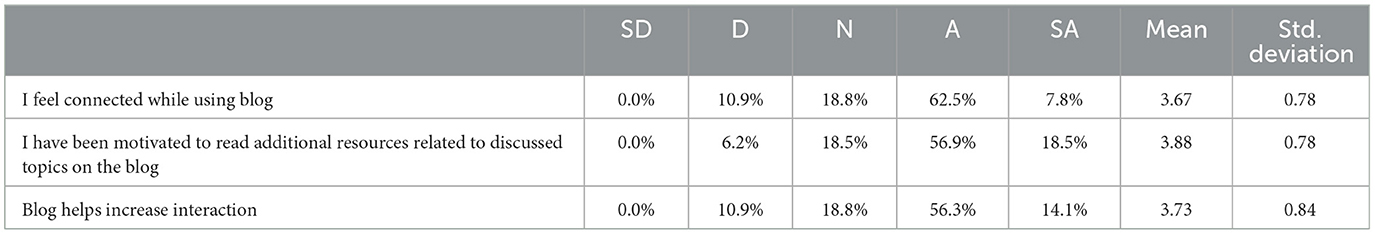

4.2 Data collection

This study collected both qualitative and quantitative data as part of an exploratory sequential mixed-method research design. Qualitative data were collected from the blogging activities of students and categorized into the following: content posts (e.g., text, image, audio, and video) and comments (e.g., questions, replies to or explanation of previous posts, and new notions). After completing a thorough analysis of the blog's activity, it was ascertained that there were 20 content postings and 71 comments made on the site during the research period. The low level of involvement can be ascribed to students' lack of familiarity with the blogging platform and the optional nature of their participation.