- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

What is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

4-minute read

- 23rd October 2023

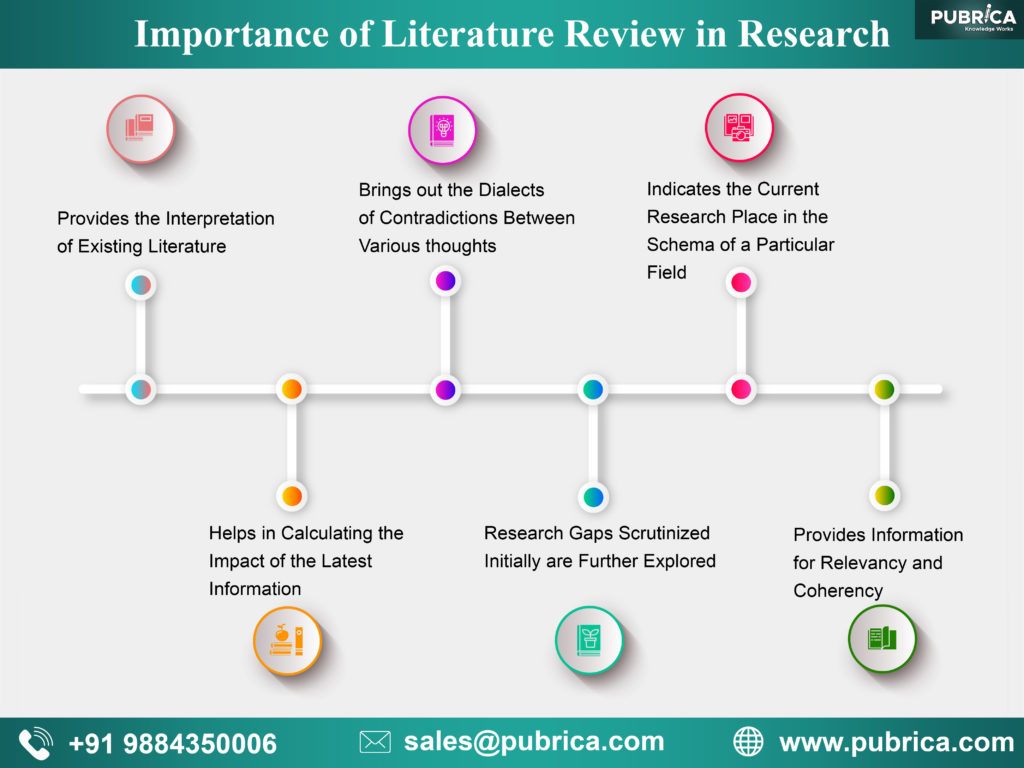

If you’re writing a research paper or dissertation , then you’ll most likely need to include a comprehensive literature review . In this post, we’ll review the purpose of literature reviews, why they are so significant, and the specific elements to include in one. Literature reviews can:

1. Provide a foundation for current research.

2. Define key concepts and theories.

3. Demonstrate critical evaluation.

4. Show how research and methodologies have evolved.

5. Identify gaps in existing research.

6. Support your argument.

Keep reading to enter the exciting world of literature reviews!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical summary and evaluation of the existing research (e.g., academic journal articles and books) on a specific topic. It is typically included as a separate section or chapter of a research paper or dissertation, serving as a contextual framework for a study. Literature reviews can vary in length depending on the subject and nature of the study, with most being about equal length to other sections or chapters included in the paper. Essentially, the literature review highlights previous studies in the context of your research and summarizes your insights in a structured, organized format. Next, let’s look at the overall purpose of a literature review.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Literature reviews are considered an integral part of research across most academic subjects and fields. The primary purpose of a literature review in your study is to:

Provide a Foundation for Current Research

Since the literature review provides a comprehensive evaluation of the existing research, it serves as a solid foundation for your current study. It’s a way to contextualize your work and show how your research fits into the broader landscape of your specific area of study.

Define Key Concepts and Theories

The literature review highlights the central theories and concepts that have arisen from previous research on your chosen topic. It gives your readers a more thorough understanding of the background of your study and why your research is particularly significant .

Demonstrate Critical Evaluation

A comprehensive literature review shows your ability to critically analyze and evaluate a broad range of source material. And since you’re considering and acknowledging the contribution of key scholars alongside your own, it establishes your own credibility and knowledge.

Show How Research and Methodologies Have Evolved

Another purpose of literature reviews is to provide a historical perspective and demonstrate how research and methodologies have changed over time, especially as data collection methods and technology have advanced. And studying past methodologies allows you, as the researcher, to understand what did and did not work and apply that knowledge to your own research.

Identify Gaps in Existing Research

Besides discussing current research and methodologies, the literature review should also address areas that are lacking in the existing literature. This helps further demonstrate the relevance of your own research by explaining why your study is necessary to fill the gaps.

Support Your Argument

A good literature review should provide evidence that supports your research questions and hypothesis. For example, your study may show that your research supports existing theories or builds on them in some way. Referencing previous related studies shows your work is grounded in established research and will ultimately be a contribution to the field.

Literature Review Editing Services

Ensure your literature review is polished and ready for submission by having it professionally proofread and edited by our expert team. Our literature review editing services will help your research stand out and make an impact. Not convinced yet? Send in your free sample today and see for yourself!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Dec 8, 2023 10:11 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

What Is A Literature Review?

A plain-language explainer (with examples).

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | June 2020 (Updated May 2023)

If you’re faced with writing a dissertation or thesis, chances are you’ve encountered the term “literature review” . If you’re on this page, you’re probably not 100% what the literature review is all about. The good news is that you’ve come to the right place.

Literature Review 101

- What (exactly) is a literature review

- What’s the purpose of the literature review chapter

- How to find high-quality resources

- How to structure your literature review chapter

- Example of an actual literature review

What is a literature review?

The word “literature review” can refer to two related things that are part of the broader literature review process. The first is the task of reviewing the literature – i.e. sourcing and reading through the existing research relating to your research topic. The second is the actual chapter that you write up in your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s look at each of them:

Reviewing the literature

The first step of any literature review is to hunt down and read through the existing research that’s relevant to your research topic. To do this, you’ll use a combination of tools (we’ll discuss some of these later) to find journal articles, books, ebooks, research reports, dissertations, theses and any other credible sources of information that relate to your topic. You’ll then summarise and catalogue these for easy reference when you write up your literature review chapter.

The literature review chapter

The second step of the literature review is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or thesis structure ). At the simplest level, the literature review chapter is an overview of the key literature that’s relevant to your research topic. This chapter should provide a smooth-flowing discussion of what research has already been done, what is known, what is unknown and what is contested in relation to your research topic. So, you can think of it as an integrated review of the state of knowledge around your research topic.

What’s the purpose of a literature review?

The literature review chapter has a few important functions within your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s take a look at these:

Purpose #1 – Demonstrate your topic knowledge

The first function of the literature review chapter is, quite simply, to show the reader (or marker) that you know what you’re talking about . In other words, a good literature review chapter demonstrates that you’ve read the relevant existing research and understand what’s going on – who’s said what, what’s agreed upon, disagreed upon and so on. This needs to be more than just a summary of who said what – it needs to integrate the existing research to show how it all fits together and what’s missing (which leads us to purpose #2, next).

Purpose #2 – Reveal the research gap that you’ll fill

The second function of the literature review chapter is to show what’s currently missing from the existing research, to lay the foundation for your own research topic. In other words, your literature review chapter needs to show that there are currently “missing pieces” in terms of the bigger puzzle, and that your study will fill one of those research gaps . By doing this, you are showing that your research topic is original and will help contribute to the body of knowledge. In other words, the literature review helps justify your research topic.

Purpose #3 – Lay the foundation for your conceptual framework

The third function of the literature review is to form the basis for a conceptual framework . Not every research topic will necessarily have a conceptual framework, but if your topic does require one, it needs to be rooted in your literature review.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the drivers of a certain outcome – the factors which contribute to burnout in office workers. In this case, you’d likely develop a conceptual framework which details the potential factors (e.g. long hours, excessive stress, etc), as well as the outcome (burnout). Those factors would need to emerge from the literature review chapter – they can’t just come from your gut!

So, in this case, the literature review chapter would uncover each of the potential factors (based on previous studies about burnout), which would then be modelled into a framework.

Purpose #4 – To inform your methodology

The fourth function of the literature review is to inform the choice of methodology for your own research. As we’ve discussed on the Grad Coach blog , your choice of methodology will be heavily influenced by your research aims, objectives and questions . Given that you’ll be reviewing studies covering a topic close to yours, it makes sense that you could learn a lot from their (well-considered) methodologies.

So, when you’re reviewing the literature, you’ll need to pay close attention to the research design , methodology and methods used in similar studies, and use these to inform your methodology. Quite often, you’ll be able to “borrow” from previous studies . This is especially true for quantitative studies , as you can use previously tried and tested measures and scales.

How do I find articles for my literature review?

Finding quality journal articles is essential to crafting a rock-solid literature review. As you probably already know, not all research is created equally, and so you need to make sure that your literature review is built on credible research .

We could write an entire post on how to find quality literature (actually, we have ), but a good starting point is Google Scholar . Google Scholar is essentially the academic equivalent of Google, using Google’s powerful search capabilities to find relevant journal articles and reports. It certainly doesn’t cover every possible resource, but it’s a very useful way to get started on your literature review journey, as it will very quickly give you a good indication of what the most popular pieces of research are in your field.

One downside of Google Scholar is that it’s merely a search engine – that is, it lists the articles, but oftentimes it doesn’t host the articles . So you’ll often hit a paywall when clicking through to journal websites.

Thankfully, your university should provide you with access to their library, so you can find the article titles using Google Scholar and then search for them by name in your university’s online library. Your university may also provide you with access to ResearchGate , which is another great source for existing research.

Remember, the correct search keywords will be super important to get the right information from the start. So, pay close attention to the keywords used in the journal articles you read and use those keywords to search for more articles. If you can’t find a spoon in the kitchen, you haven’t looked in the right drawer.

Need a helping hand?

How should I structure my literature review?

Unfortunately, there’s no generic universal answer for this one. The structure of your literature review will depend largely on your topic area and your research aims and objectives.

You could potentially structure your literature review chapter according to theme, group, variables , chronologically or per concepts in your field of research. We explain the main approaches to structuring your literature review here . You can also download a copy of our free literature review template to help you establish an initial structure.

In general, it’s also a good idea to start wide (i.e. the big-picture-level) and then narrow down, ending your literature review close to your research questions . However, there’s no universal one “right way” to structure your literature review. The most important thing is not to discuss your sources one after the other like a list – as we touched on earlier, your literature review needs to synthesise the research , not summarise it .

Ultimately, you need to craft your literature review so that it conveys the most important information effectively – it needs to tell a logical story in a digestible way. It’s no use starting off with highly technical terms and then only explaining what these terms mean later. Always assume your reader is not a subject matter expert and hold their hand through a journe y of the literature while keeping the functions of the literature review chapter (which we discussed earlier) front of mind.

Example of a literature review

In the video below, we walk you through a high-quality literature review from a dissertation that earned full distinction. This will give you a clearer view of what a strong literature review looks like in practice and hopefully provide some inspiration for your own.

Wrapping Up

In this post, we’ve (hopefully) answered the question, “ what is a literature review? “. We’ve also considered the purpose and functions of the literature review, as well as how to find literature and how to structure the literature review chapter. If you’re keen to learn more, check out the literature review section of the Grad Coach blog , as well as our detailed video post covering how to write a literature review .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Thanks for this review. It narrates what’s not been taught as tutors are always in a early to finish their classes.

Thanks for the kind words, Becky. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This website is amazing, it really helps break everything down. Thank you, I would have been lost without it.

This is review is amazing. I benefited from it a lot and hope others visiting this website will benefit too.

Timothy T. Chol [email protected]

Thank you very much for the guiding in literature review I learn and benefited a lot this make my journey smooth I’ll recommend this site to my friends

This was so useful. Thank you so much.

Hi, Concept was explained nicely by both of you. Thanks a lot for sharing it. It will surely help research scholars to start their Research Journey.

The review is really helpful to me especially during this period of covid-19 pandemic when most universities in my country only offer online classes. Great stuff

Great Brief Explanation, thanks

So helpful to me as a student

GradCoach is a fantastic site with brilliant and modern minds behind it.. I spent weeks decoding the substantial academic Jargon and grounding my initial steps on the research process, which could be shortened to a couple of days through the Gradcoach. Thanks again!

This is an amazing talk. I paved way for myself as a researcher. Thank you GradCoach!

Well-presented overview of the literature!

This was brilliant. So clear. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 20, 2024 2:57 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

Literature search for research planning and identification of research problem

Anju grewal.

Department of Anaesthesiology, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

Hanish Kataria

1 Department of Surgery, Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh, India

2 Department of Cardiac Anaesthesia, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Literature search is a key step in performing good authentic research. It helps in formulating a research question and planning the study. The available published data are enormous; therefore, choosing the appropriate articles relevant to your study in question is an art. It can be time-consuming, tiring and can lead to disinterest or even abandonment of search in between if not carried out in a step-wise manner. Various databases are available for performing literature search. This article primarily stresses on how to formulate a research question, the various types and sources for literature search, which will help make your search specific and time-saving.

INTRODUCTION

Literature search is a systematic and well-organised search from the already published data to identify a breadth of good quality references on a specific topic.[ 1 ] The reasons for conducting literature search are numerous that include drawing information for making evidence-based guidelines, a step in the research method and as part of academic assessment.[ 2 ] However, the main purpose of a thorough literature search is to formulate a research question by evaluating the available literature with an eye on gaps still amenable to further research.

Research problem[ 3 ] is typically a topic of interest and of some familiarity to the researcher. It needs to be channelised by focussing on information yet to be explored. Once we have narrowed down the problem, seeking and analysing existing literature may further straighten out the research approach.

A research hypothesis[ 4 ] is a carefully created testimony of how you expect the research to proceed. It is one of the most important tools which aids to answer the research question. It should be apt containing necessary components, and raise a question that can be tested and investigated.

The literature search can be exhaustive and time-consuming, but there are some simple steps which can help you plan and manage the process. The most important are formulating the research questions and planning your search.

FORMULATING THE RESEARCH QUESTION

Literature search is done to identify appropriate methodology, design of the study; population sampled and sampling methods, methods of measuring concepts and techniques of analysis. It also helps in determining extraneous variables affecting the outcome and identifying faults or lacunae that could be avoided.

Formulating a well-focused question is a critical step for facilitating good clinical research.[ 5 ] There can be general questions or patient-oriented questions that arise from clinical issues. Patient-oriented questions can involve the effect of therapy or disease or examine advantage versus disadvantage for a group of patients.[ 6 ]

For example, we want to evaluate the effect of a particular drug (e.g., dexmedetomidine) for procedural sedation in day care surgery patients. While formulating a research question, one should consider certain criteria, referred as ‘FINER’ (F-Feasible, I-Interesting, N-Novel, E-Ethical, R-Relevant) criteria.[ 5 ] The idea should be interesting and relevant to clinical research. It should either confirm, refute or add information to already done research work. One should also keep in mind the patient population under study and the resources available in a given set up. Also the entire research process should conform to the ethical principles of research.

The patient or study population, intervention, comparison or control arm, primary outcome, timing of measurement of outcome (PICOT) is a well-known approach for framing a leading research question.[ 7 , 8 ] Dividing the questions into key components makes it easy and searchable. In this case scenario:

- Patients (P) – What is the important group of patients? for example, day care surgery

- Intervention (I) – What is the important intervention? for example, intravenous dexmedetomidine

- Comparison (C) – What is the important intervention of comparison? for example, intravenous ketamine

- Outcome (O) – What is the effect of intervention? for example, analgesic efficacy, procedural awareness, drug side effects

- Time (T) – Time interval for measuring the outcome: Hourly for first 4 h then 4 hourly till 24 h post-procedure.

Multiple questions can be formulated from patient's problem and concern. A well-focused question should be chosen for research according to significance for patient interest and relevance to our knowledge. Good research questions address the lacunae in available literature with an aim to impact the clinical practice in a constructive manner. There are limited outcome research and relevant resources, for example, electronic database system, database and hospital information system in India. Even when these factors are available, data about existing resources is not widely accessible.[ 9 ]

TYPES OF MEDICAL LITERATURE

(Further details in chapter ‘Types of studies and research design’ in this issue).

Primary literature

Primary sources are the authentic publication of an expert's new evidence, conclusions and proposals (case reports, clinical trials, etc) and are usually published in a peer-reviewed journal. Preliminary reports, congress papers and preprints also constitute primary literature.[ 2 ]

Secondary literature

Secondary sources are systematic review articles or meta-analyses where material derived from primary source literature are infererred and evaluated.[ 2 ]

Tertiary literature

Tertiary literature consists of collections that compile information from primary or secondary literature (eg., reference books).[ 2 ]

METHODS OF LITERATURE SEARCH

There are various methods of literature search that are used alone or in combination [ Table 1 ]. For past few decades, searching the local as well as national library for books, journals, etc., was the usual practice and still physical literature exploration is an important component of any systematic review search process.[ 10 , 11 ] With the advancement of technology, the Internet is now the gateway to the maze of vast medical literature.[ 12 ] Conducting a literature review involves web-based search engines, i.e., Google, Google Scholar, etc., [ Table 2 ], or using various electronic research databases to identify materials that describe the research topic or those homologous to it.[ 13 , 14 ]

Methods of literature search

Web based methods of literature search

The various databases available for literature search include databases for original published articles in the journals [ Table 2 ] and evidence-based databases for integrated information available as systematic reviews and abstracts [ Table 3 ].[ 12 , 14 ] Most of these are not freely available to the individual user. PubMed ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ ) is the largest available resource since 1996; however, a large number of sources now provide free access to literature in the biomedical field.[ 15 ] More than 26 million citations from Medline, life science journals and online books are included in PubMed. Links to the full-text material are included in citations from PubMed Central and publisher web sites.[ 16 ] The choice of databases depends on the subject of interest and potential coverage by the different databases. Education Resources Information Centre is a free online digital library of education research and information sponsored by the Institute of Education Sciences of the U.S. Department of Education, available at http://eric.ed.gov/ . No one database can search all the medical literature. There is need to search several different databases. At a minimum, PubMed or Medline, Embase and the Cochrane central trials Registry need to be searched. When searching these databases, emphasis should be given to meta-analysis, systematic reviews randomised controlled trials and landmark studies.

Electronic source of Evidence-Based Database

Time allocated to the search needs attention as exploring and selecting data are early steps in the research method and research conducted as part of academic assessment have narrow timeframes.[ 17 ] In Indian scenario, limited outcome research and accessibility to data leads to less thorough knowledge of nature of research problem. This results in the formulation of the inappropriate research question and increases the time to literature search.

TYPES OF SEARCH

Type of search can be described in different forms according to the subject of interest. It increases the chances of retrieving relevant information from a search.

Translating research question to keywords

This will provide results based on any of the words specified; hence, they are the cornerstone of an effective search. Synonyms/alternate terms should be considered to elicit further information, i.e., barbiturates in place of thiopentone. Spellings should also be taken into account, i.e., anesthesia in place of anaesthesia (American and British). Most databases use controlled word-stock to establish common search terms (or keywords). Some of these alternative keywords can be looked from database thesaurus.[ 4 ] Another strategy is combining keywords with Boolean operators. It is important to keep a note of keywords and methods used in exploring the literature as these will need to be described later in the design of search process.

‘Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) is the National Library of Medicine's controlled hierarchical vocabulary that is used for indexing articles in PubMed, with more specific terms organised underneath more general terms’.[ 17 ] This provides a reliable way to retrieve citations that use different terminology for identical ideas, as it indexes articles based on content. Two features of PubMed that can increase yield of specific articles are ‘Automatic term mapping’ and ‘automatic term explosion’.[ 4 ]

For example, if the search keyword is heart attack, this term will match with MeSH transcription table heading and then explode into various subheadings. This helps to construct the search by adding and selecting MeSH subheadings and families of MeSH by use of hyperlinks.[ 4 ]

We can set limits to a clinical trial for retrieving higher level of evidence (i.e., randomised controlled clinical trial). Furthermore, one can browse through the link entitled ‘Related Articles’. This PubMed feature searches for similar citations using an intricate algorithm that scans titles, abstracts and MeSH terms.[ 4 ]

Phrase search

This will provide pages with only the words typed in the phrase, in that exact order and with no words in between them.

Boolean operators

AND, OR and NOT are the three Boolean operators named after the mathematician George Boole.[ 18 ] Combining two words using ‘AND’ will fetch articles that mention both the words. Using ‘OR’ will widen the search and fetch more articles that mention either subject. While using the term ‘NOT’ to combine words will fetch articles containing the first word but not the second, thus narrowing the search.

Filters can also be used to refine the search, for example, article types, text availability, language, age, sex and journal categories.

Overall, the recommendations for methodology of literature search can be as below (Creswell)[ 19 ]

- Identify keywords and use them to search articles from library and internet resources as described above

- Search several databases to search articles related to your topic

- Use thesaurus to identify terms to locate your articles

- Find an article that is similar to your topic; then look at the terms used to describe it, and use them for your search

- Use databases that provide full-text articles (free through academic libraries, Internet or for a fee) as much as possible so that you can save time searching for your articles

- If you are examining a topic for the first time and unaware of the research on it, start with broad syntheses of the literature, such as overviews, summaries of the literature on your topic or review articles

- Start with the most recent issues of the journals, and look for studies about your topic and then work backward in time. Follow-up on references at the end of the articles for more sources to examine

- Refer books on a single topic by a single author or group of authors or books that contain chapters written by different authors

- Next look for recent conference papers. Often, conference papers report the latest research developments. Contact authors of pertinent studies. Write or phone them, asking if they know of studies related to your area of interest

- The easy access and ability to capture entire articles from the web make it attractive. However, check these articles carefully for authenticity and quality and be cautious about whether they represent systematic research.

The whole process of literature search[ 20 ] is summarised in Figure 1 .

Process of literature search

Literature search provides not only an opportunity to learn more about a given topic but provides insight on how the topic was studied by previous analysts. It helps to interpret ideas, detect shortcomings and recognise opportunities. In short, systematic and well-organised research may help in designing a novel research.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example