Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

APA Sample Paper: Experimental Psychology

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Media File: APA Sample Paper: Experimental Psychology

This resource is enhanced by an Acrobat PDF file. Download the free Acrobat Reader

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

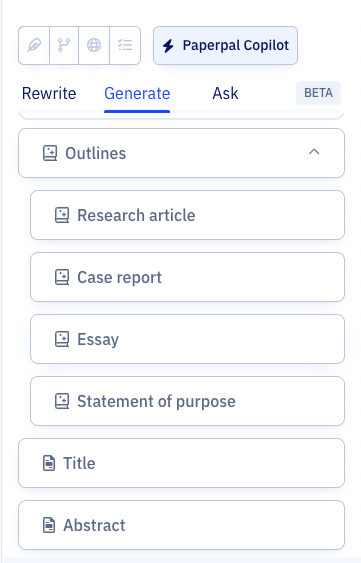

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how..., 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their..., presenting research data effectively through tables and figures.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Psychology Research Paper

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

James Lacy, MLS, is a fact-checker and researcher.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/James-Lacy-1000-73de2239670146618c03f8b77f02f84e.jpg)

Are you working on a psychology research paper this semester? Whether or not this is your first research paper, the entire process can seem a bit overwhelming at first. But, knowing where to start the research process can make things easier and less stressful.

While it can feel very intimidating, a research paper can initially be very intimidating, but it is not quite as scary if you break it down into more manageable steps. The following tips will help you break down the process into steps so it is easier to research and write your paper.

Decide What Kind of Paper You Are Going to Write

Before you begin, you should find out the type of paper your instructor expects you to write. There are a few common types of psychology papers that you might encounter.

Original Research or Lab Report

A report or empirical paper details research you conducted on your own. This is the type of paper you would write if your instructor had you perform your own psychology experiment. This type of paper follows a format similar to an APA format lab report. It includes a title page, abstract , introduction, method section, results section, discussion section, and references.

Literature Review

The second type of paper is a literature review that summarizes research conducted by other people on a particular topic. If you are writing a psychology research paper in this form, your instructor might specify the length it needs to be or the number of studies you need to cite. Student are often required to cite between 5 and 20 studies in their literature reviews and they are usually between 8 and 20 pages in length.

The format and sections of a literature review usually include an introduction, body, and discussion/implications/conclusions.

Literature reviews often begin by introducing the research question before narrowing the focus to the specific studies cited in the paper. Each cited study should be described in considerable detail. You should evaluate and compare the studies you cite and then offer your discussion of the implications of the findings.

Select an Idea for Your Research Paper

Hero Images / Getty Images

Once you have figured out the type of research paper you are going to write, it is time to choose a good topic . In many cases, your instructor may assign you a subject, or at least specify an overall theme on which to focus.

As you are selecting your topic, try to avoid general or overly broad subjects. For example, instead of writing a research paper on the general subject of attachment , you might instead focus your research on how insecure attachment styles in early childhood impact romantic attachments later in life.

Narrowing your topic will make writing your paper easier because it allows you to focus your research, develop your thesis, and fully explore pertinent findings.

Develop an Effective Research Strategy

As you find references for your psychology paper, take careful notes on the information you use and start developing a bibliography. If you stay organized and cite your sources throughout the writing process, you will not be left searching for an important bit of information you cannot seem to track back to the source.

So, as you do your research, make careful notes about each reference including the article title, authors, journal source, and what the article was about.

Write an Outline

You might be tempted to immediately dive into writing, but developing a strong framework can save a lot of time, hassle, and frustration. It can also help you spot potential problems with flow and structure.

If you outline the paper right off the bat, you will have a better idea of how one idea flows into the next and how your research supports your overall hypothesis .

You should start the outline with the three most fundamental sections: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Then, start creating subsections based on your literature review. The more detailed your outline, the easier it will be to write your paper.

Draft, Revise, and Edit

Once you are confident in your outline, it is time to begin writing. Remember to follow APA format as you write your paper and include in-text citations for any materials you reference. Make sure to cite any information in the body of your paper in your reference section at the end of your document.

Writing a psychology research paper can be intimidating at first, but breaking the process into a series of smaller steps makes it more manageable. Be sure to start early by deciding on a substantial topic, doing your research, and creating a good outline . Doing these supporting steps ahead of time make it much easier to actually write the paper when the time comes.

- Beins, BC & Beins, A. Effective Writing in Psychology: Papers, Posters, and Presentation. New York: Blackwell Publishing; 2011.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

PSY 101 - Downtown - Introduction to Psychology: Sample Papers

- Get Started

- Selecting a Topic

- Publication Types

- Find Articles

- Formatting your paper in APA style

- Quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing

- In-text and parenthetical citations

- Formatting a References Page

- Citing books and e-books

- Citing magazines, newspapers, or journal articles (print or online)

- Citing websites, online videos, blog posts, and tweets

- Citing other common formats

Sample Papers

- APA Video Tutorials

Sample papers

Sample APA paper from OWL (PDF)

- << Previous: APA FAQ's

- Next: APA Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2022 7:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.pima.edu/psy101

- Library Information

- Library Faculty and Staff

- Circulation Policies

- Library News

- Hours and Directions

- Floor Plan and Collections

- Upcoming and Past Events

- Room Use and Reservations

- Hackney Library Facts

- Mission Statement

- K.D. Kennedy, Jr. Rare Book Room

- Barton Patrons

- Print, Scan, Copy, Fax

- Print Quota

- Hardware and Software

- Interlibrary Loan

- Library Liaisons

- Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL)

- Community Patrons

- Friends of Hackney Library

- IB Students

- Greenfield School Students

- AP Seminar Students

- Wilson County Public Library Patrons

- Barton College Alumni

- Library Catalog

- Journal Finder

- Additional Sources

- Quick Questions

- Streaming Videos

- Archives and Special Collections

- A-Z List - All Resources

- Subjects A-H

- Art and Design

- Criminology and Criminal Justice

- English/Spanish

- Exercise Science

- General/Reference

- Gerontology

- Health and Physical Education

- Health Promotion

- Subjects I-T and Courses

- Mass Communications

- Mathematics

- North Carolina

- Political Science

- Quantitative Literacy (QL)

- Religion/Philosophy

- Social Studies

- Social Work

- Sport Management

- Specific Classes

- Topics and Additional Guidance

- Career Exploration

- Citation Help

- Crossing the Tracks: An Oral History of East and West Wilson, North Carolina

- Current Events

- Finding Articles

- Finding Books and Films

- Improving Thinking Skills

- PubMed Database Tutorials

- Searching Tips and Tricks

- Starting your Research

- Women's History Month

- Test Preparation

- Database Tutorials

- Reference Help

- General Reference

- Common Questions

- Books/E-Books/Electronic Literature

- Nursing Test Help

- Teacher Licensure Test Help

- Chicago Manual of Style

Service Alert

Willis N. Hackney Library

PSY 371: Experimental Psychology

- Creating a Research Plan

- Book Sources

- Journal Articles

- Other Resources

- Specific Examples/Applications of APA Style, 7th edition

Sample APA-Style Papers (7th edition)

The following links provide samples of student-paper formatting in APA's 7th edition style. The first is from APA's web site; the second is from Purdue OWL's web site.

- Sample APA Student Paper This document from the APA web site illustrates the 7th edition formatting of a student paper. This format is a simplified version of the professional paper format (excluding things like running heads, etc.).

- Purdue OWL Sample Student Paper This sample student paper in APA 7th edition comes from PurdueOWL. It can be used to supplement the example from the APA web site, or stand on its own.

The following links provide samples of professional-paper formatting in APA's 7th edition style. The first is from APA's web site; the second is from Purdue OWL's web site. The formatting of these professional papers is a bit more involved than that of the student sample papers.

- Sample APA Professional Paper This sample professional paper from the APA web site illustrates the 7th edition formatting for a paper submitted for publication to a professional journal.

- Purdue OWL Sample Professional Paper This sample paper from Purdue OWL illustrates in 7th edition formatting a professional paper. It can be used to supplement the APA sample paper or it can stand alone.

Quotations and Paraphrases in APA Style (7th edition)

- Quotations (APA 7th Edition) This link takes you to a page on the official APAstyle.org web site with information that includes how to cite both direct and indirect quotations (short and long), how to cite material for direct quotations that do not contain page numbers, and more.

- Quotations--PurdueOWL (APA 7th edition) On this "Basics: In-Text Citations" page from PurdueOWL, scroll down to see explanations and example for quotations both short (under 40 words) and long (40+ words). In addition, it gives guidance about paraphrases/summaries and how to use in-text citations to document their original source(s).

Formatting an Annotated Bibliography in APA Style (7th edition)

- Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL): Annotated Bibliographies This helpful page from PurdueOWL explains the purpose of annotated bibliographies, what they often contain, and why they're helpful.

- Guidelines for Formatting Annotated Bibliographies (APA, 7th ed.) This document provides guidance for formatting annotated bibliographies, including a sample annotated bib.

Formatting a Literature Review in APA Style (7th edition)

While APA doesn't itself provide an example of how to format a literature review, it does provide some guidance in its Publication Manual * about the content of a lit review:

Literature Reviews:

- provide summaries and evaluations of findings/theories in the research literature of a particular discipline or field;

- may include qualitative, quantitative, or a variety of other types of research;

- should define and clarify the problem being reviewed;

- summarize previous research to inform readers of where research stands currently in regard to the problem;

- identify relationships, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the current literature;

- suggest next steps or further research needed to move toward solving the problem. (APA, 2020, Section 1.6, p. 8)

* American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association: The official guide to APA style (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

- << Previous: APA Style Resources, 7th Edition

- Next: Interlibrary Loan >>

- Last Updated: Aug 9, 2022 10:27 AM

- URL: https://barton.libguides.com/psy371

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Writing a Literature Review

When writing a research paper on a specific topic, you will often need to include an overview of any prior research that has been conducted on that topic. For example, if your research paper is describing an experiment on fear conditioning, then you will probably need to provide an overview of prior research on fear conditioning. That overview is typically known as a literature review.

Please note that a full-length literature review article may be suitable for fulfilling the requirements for the Psychology B.S. Degree Research Paper . For further details, please check with your faculty advisor.

Different Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews come in many forms. They can be part of a research paper, for example as part of the Introduction section. They can be one chapter of a doctoral dissertation. Literature reviews can also “stand alone” as separate articles by themselves. For instance, some journals such as Annual Review of Psychology , Psychological Bulletin , and others typically publish full-length review articles. Similarly, in courses at UCSD, you may be asked to write a research paper that is itself a literature review (such as, with an instructor’s permission, in fulfillment of the B.S. Degree Research Paper requirement). Alternatively, you may be expected to include a literature review as part of a larger research paper (such as part of an Honors Thesis).

Literature reviews can be written using a variety of different styles. These may differ in the way prior research is reviewed as well as the way in which the literature review is organized. Examples of stylistic variations in literature reviews include:

- Summarization of prior work vs. critical evaluation. In some cases, prior research is simply described and summarized; in other cases, the writer compares, contrasts, and may even critique prior research (for example, discusses their strengths and weaknesses).

- Chronological vs. categorical and other types of organization. In some cases, the literature review begins with the oldest research and advances until it concludes with the latest research. In other cases, research is discussed by category (such as in groupings of closely related studies) without regard for chronological order. In yet other cases, research is discussed in terms of opposing views (such as when different research studies or researchers disagree with one another).

Overall, all literature reviews, whether they are written as a part of a larger work or as separate articles unto themselves, have a common feature: they do not present new research; rather, they provide an overview of prior research on a specific topic .

How to Write a Literature Review

When writing a literature review, it can be helpful to rely on the following steps. Please note that these procedures are not necessarily only for writing a literature review that becomes part of a larger article; they can also be used for writing a full-length article that is itself a literature review (although such reviews are typically more detailed and exhaustive; for more information please refer to the Further Resources section of this page).

Steps for Writing a Literature Review

1. Identify and define the topic that you will be reviewing.

The topic, which is commonly a research question (or problem) of some kind, needs to be identified and defined as clearly as possible. You need to have an idea of what you will be reviewing in order to effectively search for references and to write a coherent summary of the research on it. At this stage it can be helpful to write down a description of the research question, area, or topic that you will be reviewing, as well as to identify any keywords that you will be using to search for relevant research.

2. Conduct a literature search.

Use a range of keywords to search databases such as PsycINFO and any others that may contain relevant articles. You should focus on peer-reviewed, scholarly articles. Published books may also be helpful, but keep in mind that peer-reviewed articles are widely considered to be the “gold standard” of scientific research. Read through titles and abstracts, select and obtain articles (that is, download, copy, or print them out), and save your searches as needed. For more information about this step, please see the Using Databases and Finding Scholarly References section of this website.

3. Read through the research that you have found and take notes.

Absorb as much information as you can. Read through the articles and books that you have found, and as you do, take notes. The notes should include anything that will be helpful in advancing your own thinking about the topic and in helping you write the literature review (such as key points, ideas, or even page numbers that index key information). Some references may turn out to be more helpful than others; you may notice patterns or striking contrasts between different sources ; and some sources may refer to yet other sources of potential interest. This is often the most time-consuming part of the review process. However, it is also where you get to learn about the topic in great detail. For more details about taking notes, please see the “Reading Sources and Taking Notes” section of the Finding Scholarly References page of this website.

4. Organize your notes and thoughts; create an outline.

At this stage, you are close to writing the review itself. However, it is often helpful to first reflect on all the reading that you have done. What patterns stand out? Do the different sources converge on a consensus? Or not? What unresolved questions still remain? You should look over your notes (it may also be helpful to reorganize them), and as you do, to think about how you will present this research in your literature review. Are you going to summarize or critically evaluate? Are you going to use a chronological or other type of organizational structure? It can also be helpful to create an outline of how your literature review will be structured.

5. Write the literature review itself and edit and revise as needed.

The final stage involves writing. When writing, keep in mind that literature reviews are generally characterized by a summary style in which prior research is described sufficiently to explain critical findings but does not include a high level of detail (if readers want to learn about all the specific details of a study, then they can look up the references that you cite and read the original articles themselves). However, the degree of emphasis that is given to individual studies may vary (more or less detail may be warranted depending on how critical or unique a given study was). After you have written a first draft, you should read it carefully and then edit and revise as needed. You may need to repeat this process more than once. It may be helpful to have another person read through your draft(s) and provide feedback.

6. Incorporate the literature review into your research paper draft.

After the literature review is complete, you should incorporate it into your research paper (if you are writing the review as one component of a larger paper). Depending on the stage at which your paper is at, this may involve merging your literature review into a partially complete Introduction section, writing the rest of the paper around the literature review, or other processes.

Further Tips for Writing a Literature Review

Full-length literature reviews

- Many full-length literature review articles use a three-part structure: Introduction (where the topic is identified and any trends or major problems in the literature are introduced), Body (where the studies that comprise the literature on that topic are discussed), and Discussion or Conclusion (where major patterns and points are discussed and the general state of what is known about the topic is summarized)

Literature reviews as part of a larger paper

- An “express method” of writing a literature review for a research paper is as follows: first, write a one paragraph description of each article that you read. Second, choose how you will order all the paragraphs and combine them in one document. Third, add transitions between the paragraphs, as well as an introductory and concluding paragraph. 1

- A literature review that is part of a larger research paper typically does not have to be exhaustive. Rather, it should contain most or all of the significant studies about a research topic but not tangential or loosely related ones. 2 Generally, literature reviews should be sufficient for the reader to understand the major issues and key findings about a research topic. You may however need to confer with your instructor or editor to determine how comprehensive you need to be.

Benefits of Literature Reviews

By summarizing prior research on a topic, literature reviews have multiple benefits. These include:

- Literature reviews help readers understand what is known about a topic without having to find and read through multiple sources.

- Literature reviews help “set the stage” for later reading about new research on a given topic (such as if they are placed in the Introduction of a larger research paper). In other words, they provide helpful background and context.

- Literature reviews can also help the writer learn about a given topic while in the process of preparing the review itself. In the act of research and writing the literature review, the writer gains expertise on the topic .

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

- UCSD Library Psychology Research Guide: Literature Reviews

External Resources

- Developing and Writing a Literature Review from N Carolina A&T State University

- Example of a Short Literature Review from York College CUNY

- How to Write a Review of Literature from UW-Madison

- Writing a Literature Review from UC Santa Cruz

- Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149. doi : 1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

1 Ashton, W. Writing a short literature review . [PDF]

2 carver, l. (2014). writing the research paper [workshop]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Research Paper Structure

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

Psychology Research Paper

This sample psychology research paper features: 6000 words (approx. 20 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 32 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

History of Psychology

Every day, psychologists make history. It can be in an act as small as sending an e-mail or as large as winning a Nobel Prize. What remains of these acts and the contexts in which they occur are the data of history. When transformed by historians of psychology to produce narrative, these data represent our best attempts to make meaning of our science and profession.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, more psychology research papers:.

- Aggression Research Paper

- Artificial Intelligence Research Paper

- Discrimination Research Paper

- Early Childhood Education Research Paper

- Environmental Psychology Research Paper

- Learning Disabilities Research Paper

- Social Cognition Research Paper

The meaning that is derived from the data of history is most often made available to students of psychology through a course in the history of psychology. For a variety of reasons, the history of psychology has maintained a strong presence in the psychology curriculum at both the undergraduate and graduate levels for as long as there has been a psychology curriculum in America (Fuchs & Viney, 2002; Hilgard, Leary, & McGuire, 1991). As a result, most students will have some exposure to the subject matter and some sense of its importance.

Why are psychologists so interested in their own history? In trying to answer this question, consider the following quotations from two eminent British historians. One, Robin Collingwood (1946), wrote that the “proper object of historical study.. .is the human mind, or more properly the activities of the human mind” (p. 215). And the other, Edward H. Carr (1961), proposed that “the historian is not really interested in the unique, but what is general in the unique” and that “the study of history is a study of causes.. .the historian.. .continuously asks the question: Why?” (pp. 80, 113). Thus, according to these historians, to study history is to study the human mind, to be able to generalize beyond the characteristics of a single individual or single event to other individuals and other events, and to be able to answer the “why” of human behavior in terms of motivation, personality, past experience, expectations, and so forth. Historians are not satisfied, for example, with a mere description of the events of May 4, 1970, in which national guard troops killed four unarmed students on a college campus in Ohio. Description is useful, but it is not the scholarly end product that is sought. By itself, description is unlikely to answer the questions that historians want to answer. They want to understand an event, like the shootings at Kent State University, so completely that they can explain why it happened.

Collingwood (1946) has described history as “the science of human nature” (p. 206). In defining history in that way, Collingwood has usurped psychology’s definition for itself. One can certainly argue about the scientific nature of history and thus his use of the term science in his definition. Whereas historians do not do experimental work, they are engaged in empirical work, and they approach their questions in much the same way that psychologists do, by generating hypotheses and then seeking evidence that will confirm or disconfirm those hypotheses. Thus the intellectual pursuits of the historian and the psychologist are not really very different. And so as psychologists or students of psychology, we are not moving very far from our own field of interest when we study the history of psychology.

Historians of psychology seek to understand the development of the discipline by examining the confluence of people, places, and events within larger social, economic, and political contexts. Over the last forty years the history of psychology has become a recognized area of research and scholarship in psychology. Improvements in the tools, methods, and training of historians of psychology have created a substantial body of research that contributes to conversations about our shared past, the meaning of our present divergence, and the promise of our future. In this research-paper you will learn about the theory and practice of research on the history of psychology.

Historiography refers to the philosophy and methods of doing history. Psychology is certainly guided by underlying philosophies and a diversity of research methods. A behaviorist, for example, has certain assumptions about the influence of previous experience, in terms of a history of punishment and reinforcement, on current behavior. And the methods of study take those assumptions into account in the design and conduct of experiments. A psychoanalytic psychologist, on the other hand, has a very different philosophy and methodology in investigating the questions of interest, for example, believing in the influence of unconscious motives and using techniques such as free association or analysis of latent dream content to understand those motives. Historical research is guided in the same way. It will help you understand history by knowing something about its philosophy and methods as well.

The historical point of view is highly compatible with our notions of our science. Psychologists tend to view individuals in developmental terms, and historians of psychology extend this point of view to encompass the developmental life of the discipline. Like any area of inquiry in psychology, historians of psychology modify their theories, principles, and practices with the accumulation of knowledge, the passage of time, and available technology. One simply needs to compare E. G. Boring’s epic 1929 tome, A History of Experimental Psychology, with Duane and Sydney Ellen Schultz’s 2004 text, A History of Modern Psychology, to see the difference that 75 years can make.

Approaches to history have changed dramatically over the last 75 years. Indeed much of the early research and scholarship in the history of psychology was ceremonial and celebratory. Most often it was not written by historians. It was, and in some circles remains, a reflexive view of history—great people cause great change. Such a view is naive and simplistic. Psychological theories, research practices, and applications are all bound in a context, and it is this dynamic and fluid model that is the trend in historical research today. Just as inferential statistics have advanced from simple regression analysis to structural equation modeling, so too has historical research embraced a notion of multiple determinants and estimates of their relative impact on historical construction. In 1989 historian of psychology Laurel Furumoto christened this “the new history,” a signifier denoting that historic research should strive to be more contextual and less internal.

Postmodern, deconstructionist, and social constructionist perspectives all share an emphasis on context, and have influenced historical research in psychology. The postmodern approach embraces a more critical and questioning attitude toward the enterprise of science (Anderson, 1998). The rise of science studies has led to what some have dubbed the “science wars” and to contentious arguments between those who see science as an honest attempt at objective and dispassionate fact-finding and those who see science (psychological and otherwise) as a political exercise subject to disorder, bias, control, and authority mongering. It is an issue that is present in today’s history of psychology (for examples and discussions see Popplestone, 2004; Zammito, 2004).

Perhaps the largest growth in scholarship on the history of psychology has been in the area of intellectual history. As mentioned earlier, the construction of narrative in these works tends to eschew the older, more ceremonial, and internal histories in favor of a point of view that is more external and contextual. Rather than merely providing a combination of dates and achievements, modern historical scholarship in psychology tends to illuminate. The value of this point of view is in its contributions to our ongoing discussions of the meanings and directions of our field. The ever-expanding universe that psychology occupies and the ongoing debates of the unity of psychology are sufficient to warrant consideration and discussion of how our science and practice have evolved and developed. Historical analysis offers insight into personal, professional, and situational variables that impact and influence the field.

There is also a growing interest in what can be termed the material culture of psychology. The objects and artifacts that occupy psychological laboratories and aid our assessment of mind and behavior are becoming objects of study in their own right (Robinson, 2001; Sturm & Ash, 2005). For example, we continue to study reaction time and memory but we no longer use Hipp chronoscopes or mechanical memory drums. Changes in technology bring changes in methodologies and a host of other variables that are of interest to the historian of psychology.

Another area of increased interest and attention is the impact that racism and discrimination have had on the field. Traditionally underrepresented groups in psychology have often been made invisible by the historical record, but recent scholarship seeks to illuminate the people, places, and practices that have been part of both the problem and the solution to some of the 20th century’s most vexing questions on race, gender, and religion (for examples see Philogène, 2004; Winston, 2004).

Psychologists typically study contemporary events (behaviors and mental processes), whereas historians study events of the distant past. Both might be interested in the same behavior, but the time frame and the methods are usually distinct. Psychologists are interested in marriage, for example, and they might study marriage using surveys, ex post facto methods, or quasi-experimental designs using a sample of married couples (or perhaps divorced couples). Historians, on the other hand, would be likely to look at marriage, for example, as an institution in Victorian England, and they would be unable to use any of the methods listed previously as part of the arsenal of the psychologist. The questions on marriage that would interest psychologists and historians might be similar—how are mates selected in marriage, at what age do people marry, what roles do wives and husbands play in these marriages, what causes marriages to end? But again, the methods of research and the time frame for the events would be different.

History, then, is the branch of knowledge that attempts to analyze and explain events of the past. The explanatory product is a narrative of those events, a story. Central to telling any historical story is the accumulation of facts. We typically think of facts as some kind of demonstrable truth, some real event whose occurrence cannot be disputed. Yet facts are more elusive, as evidenced in the typical dictionary definition, which notes that a fact is information that is “presented” as objectively real. Historians present as fact, for example, that an atomic bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Because of detailed records of that event, as well as many eyewitness accounts, that fact seems indisputable; however, there are other kinds of facts.

In addition to the date of the bombing of Hiroshima, historians have also presented a number of facts relevant to the decision made by the United States government to drop that bomb. Not surprisingly, those facts are more debatable. Thus facts differ in terms of their certainty. Sometimes that is because evidence is incomplete and much inference has to be made, sometimes it is because evidence is contradictory, and sometimes it is because of bias introduced in the observation or in the interpretation of these events. Flawed though they may be, facts are the basis of history. It is the job of the historian to uncover these items of the past and to piece them together in an account that is as accurate as can be constructed.

In contemporary historiography, the researcher must always be alert to bias in the selection and interpretation of facts. Objectivity is a critical goal for the historian. Carr (1961) has argued that objectivity is indeed only a dream: “The emphasis on the role of the historian in the making of history tends, if pressed to its logical conclusion, to rule out any objective history at all: history is what the historian makes” (p. 29).

Like psychologists, historians are human too, and they bring to their task a bundle of prejudices, preconceptions, penchants, predispositions, premises, and predilections. Such baggage does not mean that they abandon their hope for objectivity, nor does it mean that their histories are hopelessly flawed. Good historians know their biases.

They use their understanding of them to search for evidence in places where they might not otherwise look or to ask questions that they would not ordinarily ask. When this searching and questioning causes them to confront facts contrary to their own views, they must deal with those facts as they would with facts that are more consistent with their biases.

Bias in history begins at the beginning: “The historian displays a bias through the mere choice of a subject…” (Gilderhus, 1992, p. 80). There are an infinite number of historical subjects to pursue. The historian selects from among those, often selecting one of paramount personal interest. The search within that subject begins with a question or questions that the historian hopes to answer, and likely the historian starts with some definite ideas about the answers to those questions.

Bias is evident too in the data of history. It can occur in primary source material—for example, census records or other government documents—even though such sources are often regarded as quite accurate. Yet such sources are inherently biased by the philosophies underlying the construction of the instruments themselves and the ways in which those instruments are used. Secondary sources too are flawed. Their errors occur in transcription, translation, selection, and interpretation.

Oral histories are subject to the biases of the interviewer and the interviewee. Some questions are asked, while others are not. Some are answered, and others are avoided. And memories of events long past are often unreliable. Manuscript collections, the substance of modern archives, are selective and incomplete. They contain the documents that someone decided were worth saving, and they are devoid of those documents that were discarded or lost for a host of reasons, perhaps known only to the discarder.

After they have selected a topic of study and gathered the facts, historians must assemble them into a narrative that can also be subject to biases. Leahey (1986) reviews some of the pitfalls that modern historians of science want to avoid. These include Whig history, presentism, internalist history, and Great Man theories. Whig history refers to historical narrative that views history as a steady movement toward progress in an orderly fashion. Presentism is the tendency to view the past in terms of current values and beliefs. Internalist history focuses solely on developments within a field and fails to acknowledge the larger social, political, and economic contexts in which events and individual actions unfold. Great Man theories credit single, unique individuals (most often white males) as makers of history without regard for the impact that the spirit of the times (often referred to as the zeitgeist) has on the achievements of individuals. Avoiding these errors of interpretation calls for a different approach, which Stocking (1965) has labeled “historicism”: an understanding of the past in its own context and for its own sake. Such an approach requires historians to immerse themselves in the context of the times they are studying.

These are just some of the hurdles that the historian faces in striving for objectivity. They are not described here to suggest that the historian’s task is a hopeless one; instead, they are meant to show the forces against which historians must struggle in attempts at accuracy and objectivity. Carr (1961) has characterized the striving for this ideal as follows:

When we call a historian objective, we mean, I think, two things. First of all, we mean that he has the capacity to rise above the limited vision of his own situation in society and in history… .Secondly, we mean that he has the capacity to project his vision into the future in such a way as to give him a more profound and lasting insight into the past than can be attained by those historians whose outlook is entirely bounded by their own immediate situation. (p. 163)

In summary, history is a product of selection and interpretation. Knowing that helps us understand why books are usually titled “A History…” and not “The History….” There are many histories of psychology, and it would be surprising to find any historians so arrogant as to presume that their individual narratives constituted “The History of Psychology.”

History research is often like detective work: the search for one piece of evidence leads to the search for another and another. One has to follow all leads, some of which produce no useful information. When all of the leads have been exhausted, then you can analyze the facts to see if they are sufficient for telling the story. The leads or the data of history are most often found in original source material. The published record provides access to original source material through monographs and serials that are widely circulated and available in most academic libraries (including reference works such as indexes, encyclopedias, and hand-books). Hard-to-find and out-of-print material (newspapers, newsletters) are now much more easily available thanks to the proliferation of electronic resources. Too often valuable sources of information (obituaries, departmental histories and records, and oral histories) that are vital to maintaining the historical record are not always catalogued and indexed in ways that make them readily available and visible. The most important of all sources of data are archival repositories. Within such repositories one can find records of individuals (referred to as manuscript collections) and organizations (termed archival collections). Manuscript collections preserve and provide access to unique documents such as correspondence, lab notes, drafts of manuscripts, grant proposals, and case records. Archival collections of organizations contain materials such as membership records, minutes of meetings, convention programs, and the like. Archival repositories provide, in essence, the “inside story,” free of editorial revision or censure and marked by the currency of time as opposed to suffering the losses and distortion of later recall. In much the same way, still images, film footage, and artifacts such as apparatus and instrumentation aid in the process of historical discovery.

There are literally thousands of collections of letters of individuals, most of them famous, but some not. And in those historically significant collections are millions of stories waiting to be told. Michael Hill (1993) has described the joys of archival research in this way:

Archival work appears bookish and commonplace to the uninitiated, but this mundane simplicity is deceptive. It bears repeating that events and materials in archives are not always what they seem on the surface. There are perpetual surprises, intrigues, and apprehensions. Suffice it to say that it is a rare treat to visit an archive, to hold in one’s hand the priceless and irreplaceable documents of our unfolding human drama. Each new box of archival material presents opportunities for discovery as well as obligations to treat the subjects of your… research with candor, theoretical sophistication, and a sense of fair play. Each archival visit is a journey into an unknown realm that rewards its visitors with challenging puzzles and unexpected revelations. (pp. 6-7)

“Surprise, intrigue, apprehension, puzzles, and discovery”—those are characteristics of detective work, and historical research is very much about detective work.

The papers of important psychologists are spread among archives and libraries all over the world. In the United States you will find the papers of William James and B. F. Skinner in the collections at Harvard University. The papers of Hugo Munsterberg, a pioneer in the application of psychology to business, can be found at the Boston Public Library. The papers of Mary Whiton Calkins and Christine Ladd-Franklin, important early contributors to experimental psychology, can be found at Wellesley College and at Vassar College and Columbia University, respectively. The Library of Congress includes the papers of James McKeen Cattell and Kenneth B. Clark. Cattell was one of the founders of American psychology and a leader among American scientists in general, and Clark, an African American psychologist, earned fame when his research on self-esteem in black children was cited prominently in the U.S. Supreme Court decision that made school segregation illegal (Brown v. Board of Education, 1954).

The single largest collection of archival materials on psychology anywhere in the world can be found at the Archives of the History of American Psychology (AHAP) at the University of Akron in Akron, Ohio. Founded by psychologists John A. Popplestone and Marion White McPherson in 1965, its purpose is to collect and preserve the historical record of psychology in America (Baker, 2004). Central to this mission is the preservation of personal papers, artifacts, and media that tell the story of psychology in America. In archival terms, “papers” refers to one-of-a-kind (unique) items. Papers can include such things as correspondence (both personal and professional), lecture notes, diaries, and lab journals. Recently named a Smithsonian Affiliate, the AHAP houses more than 1,000 objects and artifacts that offer unique insights into the science and practice of psychology. Instruments from the brass-and-glass era of the late 19th century share space alongside such significant 20th century objects as the simulated shock generator used by Stanley Milgram in his famous studies of obedience and conformity, the flags of the Eagles and Rattlers of the Robbers Cave experiment by Muzafir and Carolyn Sherif, and the props that supported Phillip Zimbardo’s well-known Stanford University prison studies.

Currently, the AHAP houses the personal papers of over 700 psychologists. There are papers of those representing experimental psychology (Leo and Dorothea Hurvich, Kenneth Spence, Ward Halstead, Mary Ainsworth, Frank Beach, Knight Dunlap, Dorothy Rethlingshafer, and Hans Lukas-Tuber), professional psychology (David Shakow, Edgar Doll, Leta Hollingworth, Herbert Freudenberger, Sidney Pressey, Joseph Zubin, Erika Fromm, Jack Bardon, Robert Waldrop, Marie Crissey, and Morris Viteles), and just about everything in between. Also included are the records of more than 50 psychological organizations, including the American Group Psychotherapy Association, the Association for Women in Psychology, Psi Chi, Psi Beta, the Association for Humanistic Psychology, the International Council of Psychologists, and the Psychonomic Society. State and regional association records that can be found at the AHAP include those of the Midwestern Psychological Association, the Ohio Psychological Association, and the Western Psychological Association. The test collection includes more than 8,000 tests and records. There are more than 15,000 photographs and 6,000 reels of film, including home movies of Freud, footage of Pavlov’s research institute, and research film from Arnold Gesell and the Yale Child Study Center. All of these materials serve as trace elements of people, places, and events to which we no longer have access. These archival elements are less fallible than human memory, and if properly preserved, are available to all for review and interpretation. Because an in-person visit to the Archives of the History of American Psychology is not always possible, the AHAP is seeking to make more of its collection available online ( https://www.uakron.edu/ahap ). Indeed, with the advent of the information age, material that was once available only by visitation to an archival repository can now be scanned, digitized, and otherwise rendered into an electronic format. From the diaries and correspondence of women during the civil war to archival collections of animation movies, the digital movement is revolutionizing access to original source material. More information on electronic resources in the history of psychology can be found in the annotated bibliography at the end of this research-paper.

All archives have a set of finding aids to help the researcher locate relevant materials. Some finding aids are more comprehensive than others. Finding aids are organized around a defined set of characteristics that typically include the following:

- Collection dates (date range of the material)

- Size of collection (expressed in linear feet)

- Provenance (place of origin of a collection, previous ownership)

- Access (if any part of the collection is restricted)

- Finding aid preparer name and date of preparation

- Biographical/historical note (a short, succinct note about the collection’s creator)

- Scope and content note (general description and highlights of the collection)

- Series descriptions (headings used to organize records of a similar nature)

- Inventory (description and location of contents of a collection)

Even if an on-site review of the contents of a collection is not possible, reviewing finding aids can still be useful because of the wealth of information they provide.

Applications

In the mid-1960s, a critical mass of sorts was achieved for those interested in teaching, research, and scholarship in the history of psychology. Within the span of a few years, two major organizations appeared: Cheiron: The International Society for the History of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, and Division 26 (Society for the History of Psychology) of the American Psychological Association (APA). Both sponsor annual meetings, and both are affiliated with scholarly journals (Cheiron is represented by the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences and the Society for the History of Psychology by History of Psychology) that provide an outlet for original research. Two doctoral training programs in the history of psychology exist in North America. One is at York University in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and the other is at the University of New Hampshire.

For most students in psychology, the closest encounter with historical research comes in the form of a project or paper as part of a requirement for a class on the history of psychology. Using the types of resources that we have described in this research-paper, it should be possible to construct a narrative on any number of topical issues in psychology.

For example, the ascendancy of professional psychology with its concomitant focus on mental health is a topic of interest to historians of psychology and of considerable importance to many students who wish to pursue graduate training in professional psychology. Using archival materials, original published material, secondary sources, and government documents, a brief example of a historical narrative is provided.

World War II and the Rise of Professional Psychology

America’s entrance into World War II greatly expanded the services that American psychologists offered, especially in the area of mental health. Rates of psychiatric illness among recruits were surprisingly high, the majority of discharges from service were for psychiatric reasons, and psychiatric casualties occupied over half of all beds in Veterans Administration hospitals. Not only was this cause for concern among the military, it also alerted federal authorities to the issue among the general population. At the time, the available supply of trained personnel met a fraction of the need. In a response that was fast and sweeping, the federal government passed the National Mental Health Act of 1946, legislation that has been a major determinant in the growth of the mental health profession in America (Pickren & Schneider, 2004). The purpose of the act was clear:

The improvement of the mental health of the people of the United States through the conducting of researches, investigations, experiments, and demonstrations relating to the cause, diagnosis, and treatment of psychiatric disorders; assisting and fostering such research activities by public and private agencies, and promoting the coordination of all such researches and activities and the useful application of their results; training personnel in matters relating to mental health; and developing, and assisting States in the use of the most effective methods of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of psychiatric disorders. (Public Law 487, 1946, p. 421)

The act provided for a massive program of federal assistance to address research, training, and service in the identification, treatment, and prevention of mental illness.

It created the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and provided broad support to psychiatry, psychiatric social work, psychiatric nursing, and psychology for the training of mental health professionals (Rubens tein, 1975). Through the joint efforts of the United States Public Health Service and the Veterans Administration, funds were made available to psychology departments willing to train professional psychologists. Never before had such large sums of money been available to academic psychology. The grants and stipends available from the federal government allowed universities to hire clinical faculty to teach graduate students, whose education and training was often supported by generous stipends. It was these funds that subsidized the Boulder Conference on Graduate Education in Clinical Psychology in 1949 (Baker & Benjamin, 2000).

The chief architect of the Boulder model was David Shakow (1901-1981). At the time, there was no other person in American psychology who had more responsibility and influence in defining standards of training for clinical psychologists. In 1947, Shakow crafted a report on the training of doctoral students in clinical psychology that became the working document for the Boulder Conference of 1949 (APA, 1947; Benjamin & Baker, 2004; Felix, 1947).

By the 1950s, professional psychologists achieved identities that served their members, served their various publics, attracted students and faculty, and ensured survival by maintaining the mechanisms necessary for professional accreditation and later for certification and licensure. In the free-market economy, many trained for public service have found greener pastures in private practice.

The training model inaugurated by the NIMH in 1949 has continued unabated for five decades, planned and supported largely through the auspices of the American Psychological Association. The exigencies that called for the creation of a competent mental health work force have changed, yet the professional psychologist engineered at mid-century has endured, as has the uneasy alliance between science and practice.

This brief historical analysis shows how archival elements can be gathered from a host of sources and used to illuminate the contextual factors that contributed to a significant development in modern American psychology. This story could not be told without access to a number of original sources. For example, the inner workings of the two-week Boulder conference are told in the surviving papers of conference participants, including the personal papers of David Shakow that are located at Akron in the Archives of the History of American Psychology. Papers relevant to the Mental Health Act of 1946 can be found in the National Archives in Washington, DC. Information about the role of the Veterans Administration in contributing to the development of the profession of clinical psychology can be found in the oral history collection available at the archives of the APA. Such analysis also offers an opportunity for reflection and evaluation, and tells us some of the story of the bifurcation of science and practice that has resulted in American psychology. We believe that historical analysis provides a perspective that can contribute to our understanding of current debates and aid in the consideration of alternatives.

Indeed, almost any contemporary topic that a student of psychology is interested in has a history that can be traced. Topics in cognition, emotions, forensics, group therapy, parenting, sexuality, memory, and animal learning, to name but a very few, can be researched. Archival resources are often more readily available than most might think. Local and regional archives and university library special collections all are sources of original material. For example, students can do interesting research on the history of their own psychology departments (Benjamin, 1990). University archives can offer minutes of faculty meetings, personnel records (those that are public), college yearbooks (which often show faculty members, student groups, etc.), course catalogues, building plans, and many more items. Interviews can be conducted with retired faculty and department staff, and local newspapers can be researched for related stories. The work can be informative, instructive, and very enjoyable.

In the end we are left with an important question: So what? What is the importance of the history of psychology? What do we gain? The history of psychology is not likely to serve as an empirically valid treatment for anxiety, nor is it likely to offer a model of how memory works. But that is not the point. It is easily argued that the history of psychology offers some instrumental benefits. The examination of psychology’s past provides not only a more meaningful understanding of that past, but a more informed and enriched appreciation of our present, and the best crystal ball available in making predictions about our field’s future. It aids critical thinking by providing a compendium of the trials, tribulations, and advances that accrue from the enormous questions we ask of our science and profession, and it offers the opportunity to reduce the interpersonal drift we seem to experience. In recent years, psychologists have become estranged from one another in ways that were unknown not all that long ago. Yet we share a connection, however tenuous, and it is found in our shared history.

At the risk of being labeled Whiggish, we would add that the history of psychology, professional and otherwise, has contributed to a corpus of knowledge that is real, tangible, and capable of improving the quality of life of all living things, including our planet. There are few secrets; we know how to encourage recycling, we understand effective ways of treating drug addiction, we have methods for alleviating some of the suffering of mental illness, we can provide tools to improve reading skills, we can design good foster homes—the list could get quite long.