Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis Essay

While being admittedly unpleasant, conflicts are virtually unavoidable and, therefore, inevitable components of everyday communication. The phenomenon of a conflict is generally defined as “an antagonistic state of opposition, disagreement or incompatibility between two or more parties” (Hussein & Al-Mmaary, 2019, p. 10). Therefore, the notion of a conflict encompasses a rather broad range of issues in personal interactions, from a misunderstanding to the feeling of mutual resentment. Typically, conflicts occur as a result of a mismatch in perspectives of the participants and the following unwillingness to compromise (Hussein & Al-Mmaary, 2019). However, conflicts represent a unique learning opportunity, namely, a chance to understand and accept others’ point of view. Thus, conflicts should be viewed not as the reasons for ceasing to communicate with opponents but, instead, as an opportunity to expand one’s perspectives and create a viable compromise.

In order to understand the nature of and core reasons for a conflict more accurately, one will need a profound theoretical perspective on the issue. Marx’s interpretation of a conflict concerns the problem of social inequality embedded into societal hierarchy and, therefore, leading to misalignment in perspectives (Tabassi et al., 2019). In other words, differences in perspectives, values, and beliefs of participants are seen as the main factors contributing to a conflict (Tabassi et al., 2019). Another theory views conflicts as a product of a mismatch in communication styles and individual differences of the parties resulting in misconceptions (Tabassi et al., 2019). Thus, the lack of mutual understanding appears to be the core premise for a conflict in all theoretical frameworks. Thus, communication behaviors that may lead to a conflict may involve direct aggression, consistent avoidance of specific issues, and the consistent avoidance of recognizing and validating the feelings of the opponents (Hussein & Al-Mmaary, 2019). Each of the specified techniques fails due to the failure to balance between the rational and emotional aspects of conflict management.

The effects that unresolved conflicts produce on relationships in different contexts are mostly detrimental. For instance, in the face-to-face setting, a conflict may cause further aggression and, possibly, physical altercations (Tabassi et al., 2019). In turn, virtual and cyber conflicts may cause instances of cyberbullying (Tabassi et al., 2019). Finally, in group communications, conflicts may cause long-lasting disagreements that cause lasting effects and impede productivity (Tabassi et al., 2019). Therefore, conflicts must be approached rationally and objectively by all participants involved.

In turn, the strategies that lead to the fastest resolution of a conflict require incorporating the acknowledgement of the participants’ emotional response to the subject matter and the development of a rational solution that will represent a compromise of all those involved. Specifically, to resolve a conflict, one needs to introduce a framework based on acknowledging one’s respect for the opponent’s viewpoint and the willingness to cooperate in order to find an option that satisfies all parties involved (Hussein & Al-Mmaary, 2019). Other conflict approaches, which are less successful and often lead to further issues, include accommodating opponents, confronting them, and avoiding a conflict (Tabassi et al., 2019). None of the three approaches above lead to an objective analysis of the situation and the effort to create a long-0lasting solution, which is why they should eb discarded.

By interpreting conflicts as the scenarios that involve a chance to learn more about others’ opinions and rationales for taking a specific stance on a certain issue, one can transform conflicts into unique learning opportunities. Therefore, confrontations and misunderstandings should be represented not as the basis for creating enmity between opponents but, instead, as the vehicle for engaging in cross-cultural exchange and learning about new perspectives and opinions. By engaging in behaviors that allow minimizing the extent of a conflict, one will ultimately achieve the most beneficial outcomes.

Hussein, A. F. F., & Al-Mamary, Y. H. S. (2019). Conflicts: Their types, and their negative and positive effects on organizations. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research , 8 (8), 10-13.

Tabassi, A. A., Abdullah, A., & Bryde, D. J. (2019). Conflict management, team coordination, and performance within multicultural temporary projects: Evidence from the construction industry . Project Management Journal , 50 (1), 101-114.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, June 24). Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/essays/interpersonal-conflict-definition-and-analysis/

"Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis." IvyPanda , 24 June 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/interpersonal-conflict-definition-and-analysis/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis'. 24 June.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis." June 24, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/interpersonal-conflict-definition-and-analysis/.

1. IvyPanda . "Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis." June 24, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/interpersonal-conflict-definition-and-analysis/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Interpersonal Conflict: Definition and Analysis." June 24, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/interpersonal-conflict-definition-and-analysis/.

- Why Medicine Needs a Dose of Evolution?

- Eye-Path and Memory-Prediction Framework

- Sex Reassignment in Treating Gender Dysphoria: A Way to Psychological Well-Being

- Ethics Awareness Inventory Analysis

- Does Age Matter in Relationships?

- Resolving Interpersonal Conflicts Within the Organization

- Psychology of Aggression and Violence

- Demand and Supply

- Urban-Rural Variations in Health: Living in Greener Areas

- Evenin’ Air Blues

- Virtual Teams and Communication Tools

- Definition of Lie in Ericsson’s “The Ways We Lie”

- Plagiarism and Originality in Personal Understanding

- Communication – Communicating in the Digital Age

- Public Speaking as the Art of Communication

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.2 Conflict and Interpersonal Communication

Learning objectives.

- Define interpersonal conflict.

- Compare and contrast the five styles of interpersonal conflict management.

- Explain how perception and culture influence interpersonal conflict.

- List strategies for effectively managing conflict.

Who do you have the most conflict with right now? Your answer to this question probably depends on the various contexts in your life. If you still live at home with a parent or parents, you may have daily conflicts with your family as you try to balance your autonomy, or desire for independence, with the practicalities of living under your family’s roof. If you’ve recently moved away to go to college, you may be negotiating roommate conflicts as you adjust to living with someone you may not know at all. You probably also have experiences managing conflict in romantic relationships and in the workplace. So think back and ask yourself, “How well do I handle conflict?” As with all areas of communication, we can improve if we have the background knowledge to identify relevant communication phenomena and the motivation to reflect on and enhance our communication skills.

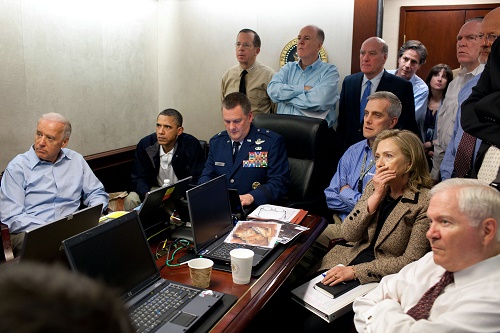

Interpersonal conflict occurs in interactions where there are real or perceived incompatible goals, scarce resources, or opposing viewpoints. Interpersonal conflict may be expressed verbally or nonverbally along a continuum ranging from a nearly imperceptible cold shoulder to a very obvious blowout. Interpersonal conflict is, however, distinct from interpersonal violence, which goes beyond communication to include abuse. Domestic violence is a serious issue and is discussed in the section “The Dark Side of Relationships.”

Interpersonal conflict is distinct from interpersonal violence, which goes beyond communication to include abuse.

Bobafred – Fist Fight – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Conflict is an inevitable part of close relationships and can take a negative emotional toll. It takes effort to ignore someone or be passive aggressive, and the anger or guilt we may feel after blowing up at someone are valid negative feelings. However, conflict isn’t always negative or unproductive. In fact, numerous research studies have shown that quantity of conflict in a relationship is not as important as how the conflict is handled (Markman et al., 1993). Additionally, when conflict is well managed, it has the potential to lead to more rewarding and satisfactory relationships (Canary & Messman, 2000).

Improving your competence in dealing with conflict can yield positive effects in the real world. Since conflict is present in our personal and professional lives, the ability to manage conflict and negotiate desirable outcomes can help us be more successful at both. Whether you and your partner are trying to decide what brand of flat-screen television to buy or discussing the upcoming political election with your mother, the potential for conflict is present. In professional settings, the ability to engage in conflict management, sometimes called conflict resolution, is a necessary and valued skill. However, many professionals do not receive training in conflict management even though they are expected to do it as part of their job (Gates, 2006). A lack of training and a lack of competence could be a recipe for disaster, which is illustrated in an episode of The Office titled “Conflict Resolution.” In the episode, Toby, the human-resources officer, encourages office employees to submit anonymous complaints about their coworkers. Although Toby doesn’t attempt to resolve the conflicts, the employees feel like they are being heard. When Michael, the manager, finds out there is unresolved conflict, he makes the anonymous complaints public in an attempt to encourage resolution, which backfires, creating more conflict within the office. As usual, Michael doesn’t demonstrate communication competence; however, there are career paths for people who do have an interest in or talent for conflict management. In fact, being a mediator was named one of the best careers for 2011 by U.S. News and World Report . [1] Many colleges and universities now offer undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees, or certificates in conflict resolution, such as this one at the University of North Carolina Greensboro: http://conflictstudies.uncg.edu/site . Being able to manage conflict situations can make life more pleasant rather than letting a situation stagnate or escalate. The negative effects of poorly handled conflict could range from an awkward last few weeks of the semester with a college roommate to violence or divorce. However, there is no absolute right or wrong way to handle a conflict. Remember that being a competent communicator doesn’t mean that you follow a set of absolute rules. Rather, a competent communicator assesses multiple contexts and applies or adapts communication tools and skills to fit the dynamic situation.

Conflict Management Styles

Would you describe yourself as someone who prefers to avoid conflict? Do you like to get your way? Are you good at working with someone to reach a solution that is mutually beneficial? Odds are that you have been in situations where you could answer yes to each of these questions, which underscores the important role context plays in conflict and conflict management styles in particular. The way we view and deal with conflict is learned and contextual. Is the way you handle conflicts similar to the way your parents handle conflict? If you’re of a certain age, you are likely predisposed to answer this question with a certain “No!” It wasn’t until my late twenties and early thirties that I began to see how similar I am to my parents, even though I, like many, spent years trying to distinguish myself from them. Research does show that there is intergenerational transmission of traits related to conflict management. As children, we test out different conflict resolution styles we observe in our families with our parents and siblings. Later, as we enter adolescence and begin developing platonic and romantic relationships outside the family, we begin testing what we’ve learned from our parents in other settings. If a child has observed and used negative conflict management styles with siblings or parents, he or she is likely to exhibit those behaviors with non–family members (Reese-Weber & Bartle-Haring, 1998).

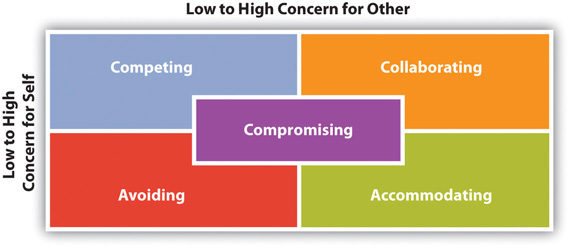

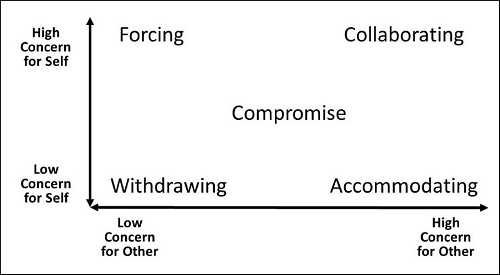

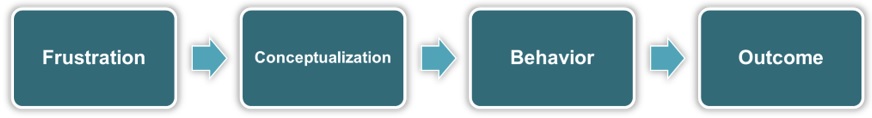

There has been much research done on different types of conflict management styles, which are communication strategies that attempt to avoid, address, or resolve a conflict. Keep in mind that we don’t always consciously choose a style. We may instead be caught up in emotion and become reactionary. The strategies for more effectively managing conflict that will be discussed later may allow you to slow down the reaction process, become more aware of it, and intervene in the process to improve your communication. A powerful tool to mitigate conflict is information exchange. Asking for more information before you react to a conflict-triggering event is a good way to add a buffer between the trigger and your reaction. Another key element is whether or not a communicator is oriented toward self-centered or other-centered goals. For example, if your goal is to “win” or make the other person “lose,” you show a high concern for self and a low concern for other. If your goal is to facilitate a “win/win” resolution or outcome, you show a high concern for self and other. In general, strategies that facilitate information exchange and include concern for mutual goals will be more successful at managing conflict (Sillars, 1980).

The five strategies for managing conflict we will discuss are competing, avoiding, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. Each of these conflict styles accounts for the concern we place on self versus other (see Figure 6.1 “Five Styles of Interpersonal Conflict Management” ).

Figure 6.1 Five Styles of Interpersonal Conflict Management

Source: Adapted from M. Afzalur Rahim, “A Measure of Styles of Handling Interpersonal Conflict,” Academy of Management Journal 26, no. 2 (1983): 368–76.

In order to better understand the elements of the five styles of conflict management, we will apply each to the follow scenario. Rosa and D’Shaun have been partners for seventeen years. Rosa is growing frustrated because D’Shaun continues to give money to their teenage daughter, Casey, even though they decided to keep the teen on a fixed allowance to try to teach her more responsibility. While conflicts regarding money and child rearing are very common, we will see the numerous ways that Rosa and D’Shaun could address this problem.

The competing style indicates a high concern for self and a low concern for other. When we compete, we are striving to “win” the conflict, potentially at the expense or “loss” of the other person. One way we may gauge our win is by being granted or taking concessions from the other person. For example, if D’Shaun gives Casey extra money behind Rosa’s back, he is taking an indirect competitive route resulting in a “win” for him because he got his way. The competing style also involves the use of power, which can be noncoercive or coercive (Sillars, 1980). Noncoercive strategies include requesting and persuading. When requesting, we suggest the conflict partner change a behavior. Requesting doesn’t require a high level of information exchange. When we persuade, however, we give our conflict partner reasons to support our request or suggestion, meaning there is more information exchange, which may make persuading more effective than requesting. Rosa could try to persuade D’Shaun to stop giving Casey extra allowance money by bringing up their fixed budget or reminding him that they are saving for a summer vacation. Coercive strategies violate standard guidelines for ethical communication and may include aggressive communication directed at rousing your partner’s emotions through insults, profanity, and yelling, or through threats of punishment if you do not get your way. If Rosa is the primary income earner in the family, she could use that power to threaten to take D’Shaun’s ATM card away if he continues giving Casey money. In all these scenarios, the “win” that could result is only short term and can lead to conflict escalation. Interpersonal conflict is rarely isolated, meaning there can be ripple effects that connect the current conflict to previous and future conflicts. D’Shaun’s behind-the-scenes money giving or Rosa’s confiscation of the ATM card could lead to built-up negative emotions that could further test their relationship.

Competing has been linked to aggression, although the two are not always paired. If assertiveness does not work, there is a chance it could escalate to hostility. There is a pattern of verbal escalation: requests, demands, complaints, angry statements, threats, harassment, and verbal abuse (Johnson & Roloff, 2000). Aggressive communication can become patterned, which can create a volatile and hostile environment. The reality television show The Bad Girls Club is a prime example of a chronically hostile and aggressive environment. If you do a Google video search for clips from the show, you will see yelling, screaming, verbal threats, and some examples of physical violence. The producers of the show choose houseguests who have histories of aggression, and when the “bad girls” are placed in a house together, they fall into typical patterns, which creates dramatic television moments. Obviously, living in this type of volatile environment would create stressors in any relationship, so it’s important to monitor the use of competing as a conflict resolution strategy to ensure that it does not lapse into aggression.

The competing style of conflict management is not the same thing as having a competitive personality. Competition in relationships isn’t always negative, and people who enjoy engaging in competition may not always do so at the expense of another person’s goals. In fact, research has shown that some couples engage in competitive shared activities like sports or games to maintain and enrich their relationship (Dindia & Baxter, 1987). And although we may think that competitiveness is gendered, research has often shown that women are just as competitive as men (Messman & Mikesell, 2000).

The avoiding style of conflict management often indicates a low concern for self and a low concern for other, and no direct communication about the conflict takes place. However, as we will discuss later, in some cultures that emphasize group harmony over individual interests, and even in some situations in the United States, avoiding a conflict can indicate a high level of concern for the other. In general, avoiding doesn’t mean that there is no communication about the conflict. Remember, you cannot not communicate . Even when we try to avoid conflict, we may intentionally or unintentionally give our feelings away through our verbal and nonverbal communication. Rosa’s sarcastic tone as she tells D’Shaun that he’s “Soooo good with money!” and his subsequent eye roll both bring the conflict to the surface without specifically addressing it. The avoiding style is either passive or indirect, meaning there is little information exchange, which may make this strategy less effective than others. We may decide to avoid conflict for many different reasons, some of which are better than others. If you view the conflict as having little importance to you, it may be better to ignore it. If the person you’re having conflict with will only be working in your office for a week, you may perceive a conflict to be temporary and choose to avoid it and hope that it will solve itself. If you are not emotionally invested in the conflict, you may be able to reframe your perspective and see the situation in a different way, therefore resolving the issue. In all these cases, avoiding doesn’t really require an investment of time, emotion, or communication skill, so there is not much at stake to lose.

Avoidance is not always an easy conflict management choice, because sometimes the person we have conflict with isn’t a temp in our office or a weekend houseguest. While it may be easy to tolerate a problem when you’re not personally invested in it or view it as temporary, when faced with a situation like Rosa and D’Shaun’s, avoidance would just make the problem worse. For example, avoidance could first manifest as changing the subject, then progress from avoiding the issue to avoiding the person altogether, to even ending the relationship.

Indirect strategies of hinting and joking also fall under the avoiding style. While these indirect avoidance strategies may lead to a buildup of frustration or even anger, they allow us to vent a little of our built-up steam and may make a conflict situation more bearable. When we hint, we drop clues that we hope our partner will find and piece together to see the problem and hopefully change, thereby solving the problem without any direct communication. In almost all the cases of hinting that I have experienced or heard about, the person dropping the hints overestimates their partner’s detective abilities. For example, when Rosa leaves the bank statement on the kitchen table in hopes that D’Shaun will realize how much extra money he is giving Casey, D’Shaun may simply ignore it or even get irritated with Rosa for not putting the statement with all the other mail. We also overestimate our partner’s ability to decode the jokes we make about a conflict situation. It is more likely that the receiver of the jokes will think you’re genuinely trying to be funny or feel provoked or insulted than realize the conflict situation that you are referencing. So more frustration may develop when the hints and jokes are not decoded, which often leads to a more extreme form of hinting/joking: passive-aggressive behavior.

Passive-aggressive behavior is a way of dealing with conflict in which one person indirectly communicates their negative thoughts or feelings through nonverbal behaviors, such as not completing a task. For example, Rosa may wait a few days to deposit money into the bank so D’Shaun can’t withdraw it to give to Casey, or D’Shaun may cancel plans for a romantic dinner because he feels like Rosa is questioning his responsibility with money. Although passive-aggressive behavior can feel rewarding in the moment, it is one of the most unproductive ways to deal with conflict. These behaviors may create additional conflicts and may lead to a cycle of passive-aggressiveness in which the other partner begins to exhibit these behaviors as well, while never actually addressing the conflict that originated the behavior. In most avoidance situations, both parties lose. However, as noted above, avoidance can be the most appropriate strategy in some situations—for example, when the conflict is temporary, when the stakes are low or there is little personal investment, or when there is the potential for violence or retaliation.

Accommodating

The accommodating conflict management style indicates a low concern for self and a high concern for other and is often viewed as passive or submissive, in that someone complies with or obliges another without providing personal input. The context for and motivation behind accommodating play an important role in whether or not it is an appropriate strategy. Generally, we accommodate because we are being generous, we are obeying, or we are yielding (Bobot, 2010). If we are being generous, we accommodate because we genuinely want to; if we are obeying, we don’t have a choice but to accommodate (perhaps due to the potential for negative consequences or punishment); and if we yield, we may have our own views or goals but give up on them due to fatigue, time constraints, or because a better solution has been offered. Accommodating can be appropriate when there is little chance that our own goals can be achieved, when we don’t have much to lose by accommodating, when we feel we are wrong, or when advocating for our own needs could negatively affect the relationship (Isenhart & Spangle, 2000). The occasional accommodation can be useful in maintaining a relationship—remember earlier we discussed putting another’s needs before your own as a way to achieve relational goals. For example, Rosa may say, “It’s OK that you gave Casey some extra money; she did have to spend more on gas this week since the prices went up.” However, being a team player can slip into being a pushover, which people generally do not appreciate. If Rosa keeps telling D’Shaun, “It’s OK this time,” they may find themselves short on spending money at the end of the month. At that point, Rosa and D’Shaun’s conflict may escalate as they question each other’s motives, or the conflict may spread if they direct their frustration at Casey and blame it on her irresponsibility.

Research has shown that the accommodating style is more likely to occur when there are time restraints and less likely to occur when someone does not want to appear weak (Cai & Fink, 2002). If you’re standing outside the movie theatre and two movies are starting, you may say, “Let’s just have it your way,” so you don’t miss the beginning. If you’re a new manager at an electronics store and an employee wants to take Sunday off to watch a football game, you may say no to set an example for the other employees. As with avoiding, there are certain cultural influences we will discuss later that make accommodating a more effective strategy.

Compromising

The compromising style shows a moderate concern for self and other and may indicate that there is a low investment in the conflict and/or the relationship. Even though we often hear that the best way to handle a conflict is to compromise, the compromising style isn’t a win/win solution; it is a partial win/lose. In essence, when we compromise, we give up some or most of what we want. It’s true that the conflict gets resolved temporarily, but lingering thoughts of what you gave up could lead to a future conflict. Compromising may be a good strategy when there are time limitations or when prolonging a conflict may lead to relationship deterioration. Compromise may also be good when both parties have equal power or when other resolution strategies have not worked (Macintosh & Stevens, 2008).

Compromising may help conflicting parties come to a resolution, but neither may be completely satisfied if they each had to give something up.

Broad Bean Media – handshake – CC BY-SA 2.0.

A negative of compromising is that it may be used as an easy way out of a conflict. The compromising style is most effective when both parties find the solution agreeable. Rosa and D’Shaun could decide that Casey’s allowance does need to be increased and could each give ten more dollars a week by committing to taking their lunch to work twice a week instead of eating out. They are both giving up something, and if neither of them have a problem with taking their lunch to work, then the compromise was equitable. If the couple agrees that the twenty extra dollars a week should come out of D’Shaun’s golf budget, the compromise isn’t as equitable, and D’Shaun, although he agreed to the compromise, may end up with feelings of resentment. Wouldn’t it be better to both win?

Collaborating

The collaborating style involves a high degree of concern for self and other and usually indicates investment in the conflict situation and the relationship. Although the collaborating style takes the most work in terms of communication competence, it ultimately leads to a win/win situation in which neither party has to make concessions because a mutually beneficial solution is discovered or created. The obvious advantage is that both parties are satisfied, which could lead to positive problem solving in the future and strengthen the overall relationship. For example, Rosa and D’Shaun may agree that Casey’s allowance needs to be increased and may decide to give her twenty more dollars a week in exchange for her babysitting her little brother one night a week. In this case, they didn’t make the conflict personal but focused on the situation and came up with a solution that may end up saving them money. The disadvantage is that this style is often time consuming, and only one person may be willing to use this approach while the other person is eager to compete to meet their goals or willing to accommodate.

Here are some tips for collaborating and achieving a win/win outcome (Hargie, 2011):

- Do not view the conflict as a contest you are trying to win.

- Remain flexible and realize there are solutions yet to be discovered.

- Distinguish the people from the problem (don’t make it personal).

- Determine what the underlying needs are that are driving the other person’s demands (needs can still be met through different demands).

- Identify areas of common ground or shared interests that you can work from to develop solutions.

- Ask questions to allow them to clarify and to help you understand their perspective.

- Listen carefully and provide verbal and nonverbal feedback.

“Getting Competent”

Handling Roommate Conflicts

Whether you have a roommate by choice, by necessity, or through the random selection process of your school’s housing office, it’s important to be able to get along with the person who shares your living space. While having a roommate offers many benefits such as making a new friend, having someone to experience a new situation like college life with, and having someone to split the cost on your own with, there are also challenges. Some common roommate conflicts involve neatness, noise, having guests, sharing possessions, value conflicts, money conflicts, and personality conflicts (Ball State University, 2001). Read the following scenarios and answer the following questions for each one:

- Which conflict management style, from the five discussed, would you use in this situation?

- What are the potential strengths of using this style?

- What are the potential weaknesses of using this style?

Scenario 1: Neatness. Your college dorm has bunk beds, and your roommate takes a lot of time making his bed (the bottom bunk) each morning. He has told you that he doesn’t want anyone sitting on or sleeping in his bed when he is not in the room. While he is away for the weekend, your friend comes to visit and sits on the bottom bunk bed. You tell him what your roommate said, and you try to fix the bed back before he returns to the dorm. When he returns, he notices that his bed has been disturbed and he confronts you about it.

Scenario 2: Noise and having guests. Your roommate has a job waiting tables and gets home around midnight on Thursday nights. She often brings a couple friends from work home with her. They watch television, listen to music, or play video games and talk and laugh. You have an 8 a.m. class on Friday mornings and are usually asleep when she returns. Last Friday, you talked to her and asked her to keep it down in the future. Tonight, their noise has woken you up and you can’t get back to sleep.

Scenario 3: Sharing possessions. When you go out to eat, you often bring back leftovers to have for lunch the next day during your short break between classes. You didn’t have time to eat breakfast, and you’re really excited about having your leftover pizza for lunch until you get home and see your roommate sitting on the couch eating the last slice.

Scenario 4: Money conflicts. Your roommate got mono and missed two weeks of work last month. Since he has a steady job and you have some savings, you cover his portion of the rent and agree that he will pay your portion next month. The next month comes around and he informs you that he only has enough to pay his half.

Scenario 5: Value and personality conflicts. You like to go out to clubs and parties and have friends over, but your roommate is much more of an introvert. You’ve tried to get her to come out with you or join the party at your place, but she’d rather study. One day she tells you that she wants to break the lease so she can move out early to live with one of her friends. You both signed the lease, so you have to agree or she can’t do it. If you break the lease, you automatically lose your portion of the security deposit.

Culture and Conflict

Culture is an important context to consider when studying conflict, and recent research has called into question some of the assumptions of the five conflict management styles discussed so far, which were formulated with a Western bias (Oetzel, Garcia, & Ting-Toomey, 2008). For example, while the avoiding style of conflict has been cast as negative, with a low concern for self and other or as a lose/lose outcome, this research found that participants in the United States, Germany, China, and Japan all viewed avoiding strategies as demonstrating a concern for the other. While there are some generalizations we can make about culture and conflict, it is better to look at more specific patterns of how interpersonal communication and conflict management are related. We can better understand some of the cultural differences in conflict management by further examining the concept of face .

What does it mean to “save face?” This saying generally refers to preventing embarrassment or preserving our reputation or image, which is similar to the concept of face in interpersonal and intercultural communication. Our face is the projected self we desire to put into the world, and facework refers to the communicative strategies we employ to project, maintain, or repair our face or maintain, repair, or challenge another’s face. Face negotiation theory argues that people in all cultures negotiate face through communication encounters, and that cultural factors influence how we engage in facework, especially in conflict situations (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). These cultural factors influence whether we are more concerned with self-face or other-face and what types of conflict management strategies we may use. One key cultural influence on face negotiation is the distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures.

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures is an important dimension across which all cultures vary. Individualistic cultures like the United States and most of Europe emphasize individual identity over group identity and encourage competition and self-reliance. Collectivistic cultures like Taiwan, Colombia, China, Japan, Vietnam, and Peru value in-group identity over individual identity and value conformity to social norms of the in-group (Dsilva & Whyte, 1998). However, within the larger cultures, individuals will vary in the degree to which they view themselves as part of a group or as a separate individual, which is called self-construal. Independent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as an individual with unique feelings, thoughts, and motivations. Interdependent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as interrelated with others (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). Not surprisingly, people from individualistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of independent self-construal, and people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of interdependent self-construal. Self-construal and individualistic or collectivistic cultural orientations affect how people engage in facework and the conflict management styles they employ.

Self-construal alone does not have a direct effect on conflict style, but it does affect face concerns, with independent self-construal favoring self-face concerns and interdependent self-construal favoring other-face concerns. There are specific facework strategies for different conflict management styles, and these strategies correspond to self-face concerns or other-face concerns.

- Accommodating. Giving in (self-face concern).

- Avoiding. Pretending conflict does not exist (other-face concern).

- Competing. Defending your position, persuading (self-face concern).

- Collaborating. Apologizing, having a private discussion, remaining calm (other-face concern) (Oetzel, Garcia, & Ting-Toomey, 2008).

Research done on college students in Germany, Japan, China, and the United States found that those with independent self-construal were more likely to engage in competing, and those with interdependent self-construal were more likely to engage in avoiding or collaborating (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). And in general, this research found that members of collectivistic cultures were more likely to use the avoiding style of conflict management and less likely to use the integrating or competing styles of conflict management than were members of individualistic cultures. The following examples bring together facework strategies, cultural orientations, and conflict management style: Someone from an individualistic culture may be more likely to engage in competing as a conflict management strategy if they are directly confronted, which may be an attempt to defend their reputation (self-face concern). Someone in a collectivistic culture may be more likely to engage in avoiding or accommodating in order not to embarrass or anger the person confronting them (other-face concern) or out of concern that their reaction could reflect negatively on their family or cultural group (other-face concern). While these distinctions are useful for categorizing large-scale cultural patterns, it is important not to essentialize or arbitrarily group countries together, because there are measurable differences within cultures. For example, expressing one’s emotions was seen as demonstrating a low concern for other-face in Japan, but this was not so in China, which shows there is variety between similarly collectivistic cultures. Culture always adds layers of complexity to any communication phenomenon, but experiencing and learning from other cultures also enriches our lives and makes us more competent communicators.

Handling Conflict Better

Conflict is inevitable and it is not inherently negative. A key part of developing interpersonal communication competence involves being able to effectively manage the conflict you will encounter in all your relationships. One key part of handling conflict better is to notice patterns of conflict in specific relationships and to generally have an idea of what causes you to react negatively and what your reactions usually are.

Identifying Conflict Patterns

Much of the research on conflict patterns has been done on couples in romantic relationships, but the concepts and findings are applicable to other relationships. Four common triggers for conflict are criticism, demand, cumulative annoyance, and rejection (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000). We all know from experience that criticism, or comments that evaluate another person’s personality, behavior, appearance, or life choices, may lead to conflict. Comments do not have to be meant as criticism to be perceived as such. If Gary comes home from college for the weekend and his mom says, “Looks like you put on a few pounds,” she may view this as a statement of fact based on observation. Gary, however, may take the comment personally and respond negatively back to his mom, starting a conflict that will last for the rest of his visit. A simple but useful strategy to manage the trigger of criticism is to follow the old adage “Think before you speak.” In many cases, there are alternative ways to phrase things that may be taken less personally, or we may determine that our comment doesn’t need to be spoken at all. I’ve learned that a majority of the thoughts that we have about another person’s physical appearance, whether positive or negative, do not need to be verbalized. Ask yourself, “What is my motivation for making this comment?” and “Do I have anything to lose by not making this comment?” If your underlying reasons for asking are valid, perhaps there is another way to phrase your observation. If Gary’s mom is worried about his eating habits and health, she could wait until they’re eating dinner and ask him how he likes the food choices at school and what he usually eats.

Demands also frequently trigger conflict, especially if the demand is viewed as unfair or irrelevant. It’s important to note that demands rephrased as questions may still be or be perceived as demands. Tone of voice and context are important factors here. When you were younger, you may have asked a parent, teacher, or elder for something and heard back “Ask nicely.” As with criticism, thinking before you speak and before you respond can help manage demands and minimize conflict episodes. As we discussed earlier, demands are sometimes met with withdrawal rather than a verbal response. If you are doing the demanding, remember a higher level of information exchange may make your demand clearer or more reasonable to the other person. If you are being demanded of, responding calmly and expressing your thoughts and feelings are likely more effective than withdrawing, which may escalate the conflict.

Cumulative annoyance is a building of frustration or anger that occurs over time, eventually resulting in a conflict interaction. For example, your friend shows up late to drive you to class three times in a row. You didn’t say anything the previous times, but on the third time you say, “You’re late again! If you can’t get here on time, I’ll find another way to get to class.” Cumulative annoyance can build up like a pressure cooker, and as it builds up, the intensity of the conflict also builds. Criticism and demands can also play into cumulative annoyance. We have all probably let critical or demanding comments slide, but if they continue, it becomes difficult to hold back, and most of us have a breaking point. The problem here is that all the other incidents come back to your mind as you confront the other person, which usually intensifies the conflict. You’ve likely been surprised when someone has blown up at you due to cumulative annoyance or surprised when someone you have blown up at didn’t know there was a problem building. A good strategy for managing cumulative annoyance is to monitor your level of annoyance and occasionally let some steam out of the pressure cooker by processing through your frustration with a third party or directly addressing what is bothering you with the source.

No one likes the feeling of rejection. Rejection can lead to conflict when one person’s comments or behaviors are perceived as ignoring or invalidating the other person. Vulnerability is a component of any close relationship. When we care about someone, we verbally or nonverbally communicate. We may tell our best friend that we miss them, or plan a home-cooked meal for our partner who is working late. The vulnerability that underlies these actions comes from the possibility that our relational partner will not notice or appreciate them. When someone feels exposed or rejected, they often respond with anger to mask their hurt, which ignites a conflict. Managing feelings of rejection is difficult because it is so personal, but controlling the impulse to assume that your relational partner is rejecting you, and engaging in communication rather than reflexive reaction, can help put things in perspective. If your partner doesn’t get excited about the meal you planned and cooked, it could be because he or she is physically or mentally tired after a long day. Concepts discussed in Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception” can be useful here, as perception checking, taking inventory of your attributions, and engaging in information exchange to help determine how each person is punctuating the conflict are useful ways of managing all four of the triggers discussed.

Interpersonal conflict may take the form of serial arguing , which is a repeated pattern of disagreement over an issue. Serial arguments do not necessarily indicate negative or troubled relationships, but any kind of patterned conflict is worth paying attention to. There are three patterns that occur with serial arguing: repeating, mutual hostility, and arguing with assurances (Johnson & Roloff, 2000). The first pattern is repeating, which means reminding the other person of your complaint (what you want them to start/stop doing). The pattern may continue if the other person repeats their response to your reminder. For example, if Marita reminds Kate that she doesn’t appreciate her sarcastic tone, and Kate responds, “I’m soooo sorry, I forgot how perfect you are,” then the reminder has failed to effect the desired change. A predictable pattern of complaint like this leads participants to view the conflict as irresolvable. The second pattern within serial arguments is mutual hostility, which occurs when the frustration of repeated conflict leads to negative emotions and increases the likelihood of verbal aggression. Again, a predictable pattern of hostility makes the conflict seem irresolvable and may lead to relationship deterioration. Whereas the first two patterns entail an increase in pressure on the participants in the conflict, the third pattern offers some relief. If people in an interpersonal conflict offer verbal assurances of their commitment to the relationship, then the problems associated with the other two patterns of serial arguing may be ameliorated. Even though the conflict may not be solved in the interaction, the verbal assurances of commitment imply that there is a willingness to work on solving the conflict in the future, which provides a sense of stability that can benefit the relationship. Although serial arguing is not inherently bad within a relationship, if the pattern becomes more of a vicious cycle, it can lead to alienation, polarization, and an overall toxic climate, and the problem may seem so irresolvable that people feel trapped and terminate the relationship (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000). There are some negative, but common, conflict reactions we can monitor and try to avoid, which may also help prevent serial arguing.

Two common conflict pitfalls are one-upping and mindreading (Gottman, 1994). is a quick reaction to communication from another person that escalates the conflict. If Sam comes home late from work and Nicki says, “I wish you would call when you’re going to be late” and Sam responds, “I wish you would get off my back,” the reaction has escalated the conflict. Mindreading is communication in which one person attributes something to the other using generalizations. If Sam says, “You don’t care whether I come home at all or not!” she is presuming to know Nicki’s thoughts and feelings. Nicki is likely to respond defensively, perhaps saying, “You don’t know how I’m feeling!” One-upping and mindreading are often reactions that are more reflexive than deliberate. Remember concepts like attribution and punctuation in these moments. Nicki may have received bad news and was eager to get support from Sam when she arrived home. Although Sam perceives Nicki’s comment as criticism and justifies her comments as a reaction to Nicki’s behavior, Nicki’s comment could actually be a sign of their closeness, in that Nicki appreciates Sam’s emotional support. Sam could have said, “I know, I’m sorry, I was on my cell phone for the past hour with a client who had a lot of problems to work out.” Taking a moment to respond mindfully rather than react with a knee-jerk reflex can lead to information exchange, which could deescalate the conflict.

Mindreading leads to patterned conflict, because we wrongly presume to know what another person is thinking.

Slipperroom – Mysterion the Mind Reader – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Validating the person with whom you are in conflict can be an effective way to deescalate conflict. While avoiding or retreating may seem like the best option in the moment, one of the key negative traits found in research on married couples’ conflicts was withdrawal, which as we learned before may result in a demand-withdrawal pattern of conflict. Often validation can be as simple as demonstrating good listening skills discussed earlier in this book by making eye contact and giving verbal and nonverbal back-channel cues like saying “mmm-hmm” or nodding your head (Gottman, 1994). This doesn’t mean that you have to give up your own side in a conflict or that you agree with what the other person is saying; rather, you are hearing the other person out, which validates them and may also give you some more information about the conflict that could minimize the likelihood of a reaction rather than a response.

As with all the aspects of communication competence we have discussed so far, you cannot expect that everyone you interact with will have the same knowledge of communication that you have after reading this book. But it often only takes one person with conflict management skills to make an interaction more effective. Remember that it’s not the quantity of conflict that determines a relationship’s success; it’s how the conflict is managed, and one person’s competent response can deescalate a conflict. Now we turn to a discussion of negotiation steps and skills as a more structured way to manage conflict.

Negotiation Steps and Skills

We negotiate daily. We may negotiate with a professor to make up a missed assignment or with our friends to plan activities for the weekend. Negotiation in interpersonal conflict refers to the process of attempting to change or influence conditions within a relationship. The negotiation skills discussed next can be adapted to all types of relational contexts, from romantic partners to coworkers. The stages of negotiating are prenegotiation, opening, exploration, bargaining, and settlement (Hargie, 2011).

In the prenegotiation stage, you want to prepare for the encounter. If possible, let the other person know you would like to talk to them, and preview the topic, so they will also have the opportunity to prepare. While it may seem awkward to “set a date” to talk about a conflict, if the other person feels like they were blindsided, their reaction could be negative. Make your preview simple and nonthreatening by saying something like “I’ve noticed that we’ve been arguing a lot about who does what chores around the house. Can we sit down and talk tomorrow when we both get home from class?” Obviously, it won’t always be feasible to set a date if the conflict needs to be handled immediately because the consequences are immediate or if you or the other person has limited availability. In that case, you can still prepare, but make sure you allot time for the other person to digest and respond. During this stage you also want to figure out your goals for the interaction by reviewing your instrumental, relational, and self-presentation goals. Is getting something done, preserving the relationship, or presenting yourself in a certain way the most important? For example, you may highly rank the instrumental goal of having a clean house, or the relational goal of having pleasant interactions with your roommate, or the self-presentation goal of appearing nice and cooperative. Whether your roommate is your best friend from high school or a stranger the school matched you up with could determine the importance of your relational and self-presentation goals. At this point, your goal analysis may lead you away from negotiation—remember, as we discussed earlier, avoiding can be an appropriate and effective conflict management strategy. If you decide to proceed with the negotiation, you will want to determine your ideal outcome and your bottom line, or the point at which you decide to break off negotiation. It’s very important that you realize there is a range between your ideal and your bottom line and that remaining flexible is key to a successful negotiation—remember, through collaboration a new solution could be found that you didn’t think of.

In the opening stage of the negotiation, you want to set the tone for the interaction because the other person will be likely to reciprocate. Generally, it is good to be cooperative and pleasant, which can help open the door for collaboration. You also want to establish common ground by bringing up overlapping interests and using “we” language. It would not be competent to open the negotiation with “You’re such a slob! Didn’t your mom ever teach you how to take care of yourself?” Instead, you may open the negotiation by making small talk about classes that day and then move into the issue at hand. You could set a good tone and establish common ground by saying, “We both put a lot of work into setting up and decorating our space, but now that classes have started, I’ve noticed that we’re really busy and some chores are not getting done.” With some planning and a simple opening like that, you can move into the next stage of negotiation.

There should be a high level of information exchange in the exploration stage. The overarching goal in this stage is to get a panoramic view of the conflict by sharing your perspective and listening to the other person. In this stage, you will likely learn how the other person is punctuating the conflict. Although you may have been mulling over the mess for a few days, your roommate may just now be aware of the conflict. She may also inform you that she usually cleans on Sundays but didn’t get to last week because she unexpectedly had to visit her parents. The information that you gather here may clarify the situation enough to end the conflict and cease negotiation. If negotiation continues, the information will be key as you move into the bargaining stage.

The bargaining stage is where you make proposals and concessions. The proposal you make should be informed by what you learned in the exploration stage. Flexibility is important here, because you may have to revise your ideal outcome and bottom line based on new information. If your plan was to have a big cleaning day every Thursday, you may now want to propose to have the roommate clean on Sunday while you clean on Wednesday. You want to make sure your opening proposal is reasonable and not presented as an ultimatum. “I don’t ever want to see a dish left in the sink” is different from “When dishes are left in the sink too long, they stink and get gross. Can we agree to not leave any dishes in the sink overnight?” Through the proposals you make, you could end up with a win/win situation. If there are areas of disagreement, however, you may have to make concessions or compromise, which can be a partial win or a partial loss. If you hate doing dishes but don’t mind emptying the trash and recycling, you could propose to assign those chores based on preference. If you both hate doing dishes, you could propose to be responsible for washing your own dishes right after you use them. If you really hate dishes and have some extra money, you could propose to use disposable (and hopefully recyclable) dishes, cups, and utensils.

In the settlement stage, you want to decide on one of the proposals and then summarize the chosen proposal and any related concessions. It is possible that each party can have a different view of the agreed solution. If your roommate thinks you are cleaning the bathroom every other day and you plan to clean it on Wednesdays, then there could be future conflict. You could summarize and ask for confirmation by saying, “So, it looks like I’ll be in charge of the trash and recycling, and you’ll load and unload the dishwasher. Then I’ll do a general cleaning on Wednesdays and you’ll do the same on Sundays. Is that right?” Last, you’ll need to follow up on the solution to make sure it’s working for both parties. If your roommate goes home again next Sunday and doesn’t get around to cleaning, you may need to go back to the exploration or bargaining stage.

Key Takeaways

- Interpersonal conflict is an inevitable part of relationships that, although not always negative, can take an emotional toll on relational partners unless they develop skills and strategies for managing conflict.

- Although there is no absolute right or wrong way to handle a conflict, there are five predominant styles of conflict management, which are competing, avoiding, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating.

- Perception plays an important role in conflict management because we are often biased in determining the cause of our own and others’ behaviors in a conflict situation, which necessitates engaging in communication to gain information and perspective.

- Culture influences how we engage in conflict based on our cultural norms regarding individualism or collectivism and concern for self-face or other-face.

- We can handle conflict better by identifying patterns and triggers such as demands, cumulative annoyance, and rejection and by learning to respond mindfully rather than reflexively.

- Of the five conflict management strategies, is there one that you use more often than others? Why or why not? Do you think people are predisposed to one style over the others based on their personality or other characteristics? If so, what personality traits do you think would lead a person to each style?

- Review the example of D’Shaun and Rosa. If you were in their situation, what do you think the best style to use would be and why?

- Of the conflict triggers discussed (demands, cumulative annoyance, rejection, one-upping, and mindreading) which one do you find most often triggers a negative reaction from you? What strategies can you use to better manage the trigger and more effectively manage conflict?

Ball State University, “Roommate Conflicts,” accessed June 16, 2001, http://cms.bsu.edu/CampusLife/CounselingCenter/VirtualSelfHelpLibrary/RoommateIssues.aspx .

Bobot, L., “Conflict Management in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 27, no. 3 (2010): 296.

Cai, D. A. and Edward L. Fink, “Conflict Style Differences between Individualists and Collectivists,” Communication Monographs 69, no. 1 (2002): 67–87.

Canary, D. J. and Susan J. Messman, “Relationship Conflict,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook , eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 261–70.

Christensen, A. and Neil S. Jacobson, Reconcilable Differences (New York: Guilford Press, 2000), 17–20.

Dindia, K. and Leslie A. Baxter, “Strategies for Maintaining and Repairing Marital Relationships,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 4, no. 2 (1987): 143–58.

Dsilva, M. U. and Lisa O. Whyte, “Cultural Differences in Conflict Styles: Vietnamese Refugees and Established Residents,” Howard Journal of Communication 9 (1998): 59.

Gates, S., “Time to Take Negotiation Seriously,” Industrial and Commercial Training 38 (2006): 238–41.

Gottman, J. M., What Predicts Divorce?: The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994). One-upping

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 406–7, 430.

Isenhart, M. W. and Michael Spangle, Collaborative Approaches to Resolving Conflict (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 26.

Johnson, K. L. and Michael E. Roloff, “Correlates of the Perceived Resolvability and Relational Consequences of Serial Arguing in Dating Relationships: Argumentative Features and the Use of Coping Strategies,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17, no. 4–5 (2000): 677–78.

Macintosh, G. and Charles Stevens, “Personality, Motives, and Conflict Strategies in Everyday Service Encounters,” International Journal of Conflict Management 19, no. 2 (2008): 115.

Markman, H. J., Mari Jo Renick, Frank J. Floyd, Scott M. Stanley, and Mari Clements, “Preventing Marital Distress through Communication and Conflict Management Training: A 4- and 5-Year Follow-Up,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61, no. 1 (1993): 70–77.

Messman, S. J. and Rebecca L. Mikesell, “Competition and Interpersonal Conflict in Dating Relationships,” Communication Reports 13, no. 1 (2000): 32.

Oetzel, J., Adolfo J. Garcia, and Stella Ting-Toomey, “An Analysis of the Relationships among Face Concerns and Facework Behaviors in Perceived Conflict Situations: A Four-Culture Investigation,” International Journal of Conflict Management 19, no. 4 (2008): 382–403.

Reese-Weber, M. and Suzanne Bartle-Haring, “Conflict Resolution Styles in Family Subsystems and Adolescent Romantic Relationships,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 27, no. 6 (1998): 735–52.

Sillars, A. L., “Attributions and Communication in Roommate Conflicts,” Communication Monographs 47, no. 3 (1980): 180–200.

- “Mediator on Best Career List for 2011,” UNCG Program in Conflict and Peace Studies Blog, accessed November 5, 2012, http://conresuncg.blogspot.com/2011/04/mediator-on-best-career-list-for-2011.html . ↵

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Browse Topics

- Executive Committee

- Affiliated Faculty

- Harvard Negotiation Project

- Great Negotiator

- American Secretaries of State Project

- Awards, Grants, and Fellowships

- Negotiation Programs

- Mediation Programs

- One-Day Programs

- In-House Training and Custom Programs

- In-Person Programs

- Online Programs

- Advanced Materials Search

- Contact Information

- The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Negotiation Journal

- Harvard Negotiation Law Review

- Working Conference on AI, Technology, and Negotiation

- 40th Anniversary Symposium

- Free Reports and Program Guides

Free Videos

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Event Series

- Our Mission

- Keyword Index

PON – Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School - https://www.pon.harvard.edu

Team-Building Strategies: Building a Winning Team for Your Organization

Discover how to build a winning team and boost your business negotiation results in this free special report, Team Building Strategies for Your Organization, from Harvard Law School.

Interpersonal Conflict Resolution: Beyond Conflict Avoidance

Interpersonal conflict resolution and conflict management can be intimidating, but generally, avoidance only worsens conflict. here’s advice on how to become comfortable dealing with conflict..

By Katie Shonk — on February 20th, 2024 / Conflict Resolution

To hear some tell it, we are experiencing an epidemic of conflict avoidance, finding new ways to walk away from conflict rather than engaging in interpersonal conflict resolution. Ghosting, for example—ending a relationship by disappearing—has become common . Numerous tech companies are being criticized for laying off people via email rather than in person. Many people experience the pain of estrangement from family members, which can arise without warning or explanation. And whether you view the recently documented phenomenon of “ quiet quitting ” as destructive slacking or healthy boundary setting , it can manifest as avoidance of hard conversations and negotiations about workload.

There can be legitimate reasons for avoiding conflict, such as the need to break off an abusive relationship. But in many cases, interpersonal conflict resolution could help repair a relationship, to the benefit of all involved, or end it with less pain. Through a better understanding of conflict avoidance, we can become more comfortable with interpersonal conflict resolution at work and in our personal lives.

Claim your FREE copy: The New Conflict Management

In our FREE special report from the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School - The New Conflict Management: Effective Conflict Resolution Strategies to Avoid Litigation – renowned negotiation experts uncover unconventional approaches to conflict management that can turn adversaries into partners.

Why Do We Avoid Conflict?

We choose to avoid conflict for numerous reasons. “A lot of people anticipate that talking about how they feel is going to be a confrontation,” psychologist Jennice Vilhauer told the New York Times . “That mental expectation makes people want to avoid things that make them uncomfortable.” Relatedly, the fear of being emotionally vulnerable with others can lead us to avoid conflict and resist interpersonal conflict resolution.

Some people are especially prone to avoiding conflict. “Conflict avoidance is a type of people-pleasing behavior that typically arises from a deep-rooted fear of upsetting others,” according to Healthline . “Many of these tendencies can be traced back to growing up in an environment that was dismissive or hypercritical.”

Research showing that social anxiety is growing among young people worldwide could also help to explain a recent rise in conflict avoidance. And the lack of accountability created by modern technology may play a role. Whether we are laying off someone, leaving a job, or ending a romantic relationship, texts and emails allow us to avoid having such difficult conversations in real time, face-to-face.

How Conflict Avoidance Harms Us

Conflict avoidance often harms us and others. When we avoid conflict with those we continue to interact with, we allow it to fester and grow. Imagine that you hear that you hurt a coworker’s feelings with a thoughtless remark. You feel awkward about the situation and unsure about how to bring it up. Conflict avoidance on both sides could lead your work relationship to grow uncomfortable and distant. By contrast, taking the coworker aside to discuss what happened and apologize would likely repair the relationship and set up productive future interactions.

“Avoiding conflict can compromise our resilience, mental health, and productivity in the long term,” writes Andrew Reiner for NBC News . By contrast, one study of over 2,000 people aged 33 to 84 found that those who intentionally resolved daily conflicts reported that their stress diminished. They also experienced fewer negative emotions than others in the study, and their positive emotions remained stable for longer periods of time.

Toward Interpersonal Conflict Resolution

How can we overcome the urge to avoid conflict and move toward engaging in interpersonal conflict resolution more frequently? Here are some guidelines:

Recognize the costs of avoidance. Look beyond the temporary sense of safety and calm that conflict avoidance can bring and recognize what you stand to lose from it—such as broken relationships, a damaged reputation, and strained interactions at work or at home.

Practice on smaller issues. If you’re used to sweeping conflict under the rug, interpersonal conflict resolution can feel deeply threatening. You might try to build your skills and confidence by opening up conversations about relatively small matters with those you trust the most. Positive experiences resolving minor issues, such as household chores that aren’t getting done, can equip you to take on bigger concerns.

Make a plan. Think through—and perhaps write down—the best way to cope with a conflict before reaching out to the other person or people involved. In particular, to get a broader perspective, consider how your actions—or inaction—might be affecting them.

Get help. A trusted friend or counselor might help you view the conflict more fully and determine the best way to manage it. You might also consider asking a third party, such as your boss, to help mediate the dispute, or consider formal mediation.

Set the foundation for collaboration and honesty. When approaching the person with whom you are in conflict, you might acknowledge the discomfort you feel before explaining why you believe it is important to talk things through. If you believe you have been wronged, rather than lashing out in anger, present your interpretation of the situation, and ask the other person to describe how they see things. If you’ve hurt the other person, take responsibility for your actions and be prepared to apologize before discussing how to move forward.

What other advice do you have for avoiding conflict and moving toward interpersonal conflict resolution?

Related Posts

- 3 Types of Conflict and How to Address Them

- Negotiation with Your Children: How to Resolve Family Conflicts

- What is Conflict Resolution, and How Does It Work?

- Conflict Styles and Bargaining Styles

- Value Conflict: What It Is and How to Resolve It

Click here to cancel reply.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Negotiation and Leadership

- Learn More about Negotiation and Leadership

NEGOTIATION MASTER CLASS

- Learn More about Harvard Negotiation Master Class

Negotiation Essentials Online

- Learn More about Negotiation Essentials Online

Beyond the Back Table: Working with People and Organizations to Get to Yes

- Learn More about Beyond the Back Table

Select Your Free Special Report

- Beyond the Back Table September 2024 and February 2025 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Fall 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Essentials Online (NEO) Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Master Class May 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Make the Most of Online Negotiations

- Managing Multiparty Negotiations

- Getting the Deal Done

- Salary Negotiation: How to Negotiate Salary: Learn the Best Techniques to Help You Manage the Most Difficult Salary Negotiations and What You Need to Know When Asking for a Raise

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiation: Cross Cultural Communication Techniques and Negotiation Skills From International Business and Diplomacy

Teaching Negotiation Resource Center

- Teaching Materials and Publications

Stay Connected to PON

Preparing for negotiation.

Understanding how to arrange the meeting space is a key aspect of preparing for negotiation. In this video, Professor Guhan Subramanian discusses a real world example of how seating arrangements can influence a negotiator’s success. This discussion was held at the 3 day executive education workshop for senior executives at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

Guhan Subramanian is the Professor of Law and Business at the Harvard Law School and Professor of Business Law at the Harvard Business School.

Articles & Insights

- Negotiation Examples: How Crisis Negotiators Use Text Messaging

- For Sellers, The Anchoring Effects of a Hidden Price Can Offer Advantages

- BATNA Examples—and What You Can Learn from Them

- Taylor Swift: Negotiation Mastermind?

- Power and Negotiation: Advice on First Offers

- Amazon–Whole Foods Negotiation: Did the Exclusive Courtship Move Too Fast?

- 10 Great Examples of Negotiation in Business

- The Process of Business Negotiation

- Contingency Contracts in Business Negotiations

- Sales Negotiation Techniques

- Police Negotiation Techniques from the NYPD Crisis Negotiations Team

- Famous Negotiations Cases – NBA and the Power of Deadlines at the Bargaining Table

- Negotiating Change During the Covid-19 Pandemic

- AI Negotiation in the News

- Crisis Communication Examples: What’s So Funny?

- Bargaining in Bad Faith: Dealing with “False Negotiators”

- Managing Difficult Employees, and Those Who Just Seem Difficult

- How to Deal with Difficult Customers

- Negotiating with Difficult Personalities and “Dark” Personality Traits

- Consensus-Building Techniques

- 7 Tips for Closing the Deal in Negotiations

- How Does Mediation Work in a Lawsuit?

- Dealmaking Secrets from Henry Kissinger

- Writing the Negotiated Agreement

- The Winner’s Curse: Avoid This Common Trap in Auctions

- What are the Three Basic Types of Dispute Resolution? What to Know About Mediation, Arbitration, and Litigation

- Four Conflict Negotiation Strategies for Resolving Value-Based Disputes

- The Door in the Face Technique: Will It Backfire?

- Three Questions to Ask About the Dispute Resolution Process

- Negotiation Case Studies: Google’s Approach to Dispute Resolution

- India’s Direct Approach to Conflict Resolution

- International Negotiations and Agenda Setting: Controlling the Flow of the Negotiation Process

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiations and the Importance of Communication in International Business Deals

- Political Negotiation: Negotiating with Bureaucrats

- Government Negotiations: The Brittney Griner Case

- The Contingency Theory of Leadership: A Focus on Fit

- Directive Leadership: When It Does—and Doesn’t—Work

- How an Authoritarian Leadership Style Blocks Effective Negotiation

- Paternalistic Leadership: Beyond Authoritarianism

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Leadership Styles: Uncovering Bias and Generating Mutual Gains

- Undecided on Your Dispute Resolution Process? Combine Mediation and Arbitration, Known as Med-Arb

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Training: Mediation Curriculum

- What Makes a Good Mediator?

- Why is Negotiation Important: Mediation in Transactional Negotiations

- The Mediation Process and Dispute Resolution

- The Right Negotiation Environment: Your Place or Mine?

- Negotiation Skills: How to Become a Negotiation Master

- Dear Negotiation Coach: Should You Say Thank You for Concessions in Negotiations?

- Persuasion Tactics in Negotiation: Playing Defense

- Negotiation in International Relations: Finding Common Ground

- Ethics and Negotiation: 5 Principles of Negotiation to Boost Your Bargaining Skills in Business Situations

- Negotiation Journal celebrates 40th anniversary, new publisher, and diamond open access in 2024

- 10 Negotiation Training Skills Every Organization Needs

- Trust in Negotiation: Does Gender Matter?

- Use a Negotiation Preparation Worksheet for Continuous Improvement

- Negotiating a Salary When Compensation Is Public

- How to Negotiate a Higher Salary after a Job Offer

- How to Negotiate Pay in an Interview

- How to Negotiate a Higher Salary

- Renegotiate Salary to Your Advantage

- Check Out the International Investor-State Arbitration Video Course

- Teaching with Multi-Round Simulations: Balancing Internal and External Negotiations

- Check Out Videos from the PON 40th Anniversary Symposium

- Camp Lemonnier: Negotiating a Lease Agreement for a Key Military Base in Africa

- New Great Negotiator Case and Video: Christiana Figueres, former UNFCCC Executive Secretary

- Win-Win Negotiation: Managing Your Counterpart’s Satisfaction

- Win-Lose Negotiation Examples

- How to Negotiate Mutually Beneficial Noncompete Agreements

- What is a Win-Win Negotiation?

- How to Win at Win-Win Negotiation

PON Publications

- Negotiation Data Repository (NDR)

- New Frontiers, New Roleplays: Next Generation Teaching and Training

- Negotiating Transboundary Water Agreements

- Learning from Practice to Teach for Practice—Reflections From a Novel Training Series for International Climate Negotiators

- Insights From PON’s Great Negotiators and the American Secretaries of State Program

- Gender and Privilege in Negotiation

Remember Me This setting should only be used on your home or work computer.

Lost your password? Create a new password of your choice.

Copyright © 2024 Negotiation Daily. All rights reserved.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Navigate Conflict with a Coworker

Seven strategies to help you make progress with even the most difficult people

Interpersonal conflicts are common in the workplace, and it’s easy to get caught up in them. But that can lead to reduced creativity, slower and worse decision-making, and even fatal mistakes. So how can we return to our best selves? Having studied conflict management and resolution over the past several years, the author outlines seven principles to help you work more effectively with difficult colleagues: (1) Understand that your perspective is not the only one possible. (2) Be aware of and question any unconscious biases you may be harboring. (3) View the conflict not as me-versus-them but as a problem to be jointly solved. (4) Understand what outcome you’re aiming for. (5) Be very judicious in discussing the issue with others. (6) Experiment with behavior change to find out what will improve the situation. (7) Make sure to stay curious about the other person and how you can more effectively work together.

Early in my career I took a job reporting to someone who had a reputation for being difficult. I’ll call her Elise. Plenty of people warned me that she would be hard to work with, but I thought I could handle it. I prided myself on being able to get along with anyone. I didn’t let people get under my skin. I could see the best in everyone.

- Amy Gallo is a contributing editor at Harvard Business Review, cohost of the Women at Work podcast , and the author of two books: Getting Along: How to Work with Anyone (Even Difficult People) and the HBR Guide to Dealing with Conflict . She writes and speaks about workplace dynamics. Watch her TEDx talk on conflict and follow her on LinkedIn . amyegallo

Partner Center

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology