- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A Look At Afghanistan's 40 Years Of Crisis — From The Soviet War To Taliban Recapture

Hannah Bloch

The Soviet army in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Dec. 31, 1979. Francois Lochon/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images hide caption

The Soviet army in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Dec. 31, 1979.

The collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban's recapture of power came after a blitz by the militant group that stunned many Afghans and the world. It is the latest chapter in the country's nearly 42 years of instability and bitter conflict.

Afghans have lived through foreign invasions, civil war, insurgency and a previous period of oppressive Taliban rule. Here are some key events and dates from the past four decades.

The Soviet war years

December 1979

Following upheaval after a 1978 Afghan coup, the Soviet military invades Afghanistan to prop up a pro-Soviet government.

Babrak Karmal is installed as Afghanistan's Soviet-backed ruler. Groups of guerrilla fighters known as mujahideen or holy warriors mount opposition and a jihad against Soviet forces. The ensuing war leaves about 1 million Afghan civilians and some 15,000 Soviet soldiers dead.

Millions of Afghans begin fleeing to neighboring Pakistan as refugees. The U.S., which had previously been aiding Afghan mujahideen groups, and Saudi Arabia covertly funnel arms to the mujahideen via Pakistan through the 1980s.

Afghan refugees are shown in a camp on Kohat Road outside of Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1980. Peter Bregg/AP hide caption

Afghan refugees are shown in a camp on Kohat Road outside of Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1980.

President Ronald Reagan welcomes Afghan fighters to the White House in 1983, and mujahideen leader Yunus Khalis visits the Oval Office in 1987.

Former President Ronald Reagan meets in the Oval Office in 1983 with Afghan fighters opposing the Soviet Union. Bettmann/Getty Images hide caption

Former President Ronald Reagan meets in the Oval Office in 1983 with Afghan fighters opposing the Soviet Union.

The CIA supplies Stinger antiaircraft missiles to the mujahideen, allowing them to shoot down Soviet helicopter gunships.

An Afghan guerrilla handles a U.S.-made Stinger anti-aircraft missile. David Stewart Smith/AP hide caption

An Afghan guerrilla handles a U.S.-made Stinger anti-aircraft missile.

Mohammad Najibullah, groomed by the Soviets, replaces Karmal as president.

The Geneva peace accords are signed by Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, the U.S. and Pakistan, and Soviet forces begin their withdrawal.

Feb. 15, 1989

The last Soviet to leave Afghanistan, Lt. Gen. Boris Gromov, walks with his son on the bridge linking Afghanistan to Uzbekistan over the Amu Darya River. The Soviet commander crossed from the Afghan town of Khairaton. Tass/AP hide caption

The last Soviet to leave Afghanistan, Lt. Gen. Boris Gromov, walks with his son on the bridge linking Afghanistan to Uzbekistan over the Amu Darya River. The Soviet commander crossed from the Afghan town of Khairaton.

The last Soviet soldier leaves Afghanistan.

The 1990s to 2001: Civil war followed by Taliban rule

Following the withdrawal of Soviet forces and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Najibullah's pro-communist government crumbles. He is blocked from leaving Afghanistan and takes refuge at the Kabul United Nations compound, where he remains for more than four years.

Mujahideen leaders enter the capital and turn on each other. Refugees continue to flee in huge numbers to Pakistan and Iran.

The presidential palace in Kabul is severely damaged after being hit by tank shells and rockets fired by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e-Islami fighters. Udo Weitz/AP hide caption

The presidential palace in Kabul is severely damaged after being hit by tank shells and rockets fired by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e-Islami fighters.

Kabul, largely spared during the Soviet war, comes under brutal attack by forces loyal to mujahideen leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Much of the city is left in rubble. The national museum is rocketed and looted. Some 50,000 people are killed.

The Taliban, ultraconservative Afghan student-warriors emerging from mujahideen groups and religious seminaries in Pakistan and Afghanistan, take over the southern Afghan city of Kandahar, promising to restore order and bring greater security. They quickly impose their harsh interpretation of Islam on the territory they control.

A Taliban fighter guards a road southeast of Kabul in 1995. Saeed Khan/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

A Taliban fighter guards a road southeast of Kabul in 1995.

Saudi-born al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden arrives in Afghanistan after being expelled from Sudan, and eventually ingratiates himself with the one-eyed Taliban supreme leader, Mullah Mohammad Omar. Bin Laden had previously aided Afghan mujahideen forces during the Soviet war years as one of many so-called "Afghan Arabs" who joined the anti-Soviet fight.

Osama bin Laden speaks at a press conference in Khost, Afghanistan, in 1998. Mazhar Ali Khan/AP hide caption

Osama bin Laden speaks at a press conference in Khost, Afghanistan, in 1998.

Sept. 26, 1996

The Taliban take over Kabul. They capture Najibullah, the former president, from the U.N. compound, kill him and hang his body from a lamppost.

Taliban rally in Kabul, October 1996. Robert Nickelsberg/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images hide caption

Taliban rally in Kabul, October 1996.

Gaining control over most of the country, the Taliban impose their rule, forbidding most women from working, banning girls from education and carrying out punishments including beatings, amputations and public executions. Only three countries officially recognize the Taliban regime: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

In August 1998, the U.S. launches cruise missile strikes on Khost, Afghanistan, in retaliation for al-Qaida attacks on U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

Afghan women wear Taliban-imposed burqas in Kabul. Roger Lemoyne/Liaison/Getty Images hide caption

Afghan women wear Taliban-imposed burqas in Kabul.

The U.N. Security Council imposes terrorist sanctions on the Taliban and al-Qaida.

In December, an Indian Airlines passenger jet, bound from Kathmandu to New Delhi, is hijacked to Kandahar. The Taliban serve as mediators between the hijackers and Indian authorities, who decide to free three terrorists from Indian prisons and hand them over to the hijackers in exchange for the passengers' safety.

Rejecting international pleas, the Taliban blow up two 1,500-year-old colossal Buddha statues carved into a mountainside in Bamiyan, saying the statues were "idols" prohibited under Islam.

Afghan Taliban in front of the empty niche that held one of the two giant Buddha statues the Taliban blew up in Bamiyan in March 2001. Saeed Khan/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

Afghan Taliban in front of the empty niche that held one of the two giant Buddha statues the Taliban blew up in Bamiyan in March 2001.

August 2001

The Taliban put a group of Western aid workers on trial, accusing them of preaching Christianity, a capital offense. Two American women are among the accused.

September 2001

Anti-Taliban Northern Alliance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud is assassinated on Sept. 9 by al-Qaida operatives posing as TV journalists.

After al-Qaida's Sept. 11 attacks in New York City and Washington, the U.S. demands that the Taliban hand over bin Laden. They refuse.

The U.S.-led invasion

Oct. 7, 2001

An undated file photo shows a U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress heavy bomber. The U.S.-led coalition launched air and missile strikes in Afghanistan on Oct. 7, 2001. U.S. Air Force/Getty Images hide caption

An undated file photo shows a U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress heavy bomber. The U.S.-led coalition launched air and missile strikes in Afghanistan on Oct. 7, 2001.

A U.S.-led coalition launches Operation Enduring Freedom, targeting the Taliban and al-Qaida with military strikes.

November-December 2001

The U.S.-backed Northern Alliance enters Kabul on Nov. 13. The Taliban flee south and their regime is overthrown. In December, Hamid Karzai is named interim president after Afghan groups sign the Bonn Agreement on an interim government. Under that agreement, some warlords are named provincial governors, military commanders and cabinet ministers, as are members of the Northern Alliance. The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force is established under a U.N. mandate.

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld signals an end to "major combat activity" in Afghanistan, saying, "We clearly have moved from major combat activity to a period of stability and stabilization and reconstruction and activities."

Afghanistan holds a presidential election, won by Hamid Karzai.

Afghanistan's parliament opens after elections bring in lawmakers including old warlords and faction leaders.

The Taliban reemerge

The Taliban seize territory in southern Afghanistan. NATO's ISAF assumes command from the U.S. in the south, something the NATO secretary general calls "one of the most challenging tasks NATO has ever taken on."

Karzai is reelected president.

The U.S. "surge" begins after President Barack Obama orders substantial troop increases in Afghanistan. Obama says that U.S. forces will leave by 2011.

NATO announces it will withdraw foreign combat troops and transfer control of security operations to Afghan forces by the end of 2014.

The Afghan army takes on security operations from NATO forces.

The Obama administration announces plans to start formal peace talks with the Taliban.

After a disputed election, Ashraf Ghani succeeds Karzai as Afghanistan's president. Ghani's rival, Abdullah Abdullah, is named chief executive.

A U.S. soldier walks past burning trucks at the scene of a suicide attack in Afghanistan's Nangarhar province in 2014. Noorullah Shirzada/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

A U.S. soldier walks past burning trucks at the scene of a suicide attack in Afghanistan's Nangarhar province in 2014.

At the end of the year, U.S. and NATO forces formally end their combat missions.

NATO launches its Resolute Support mission to aid Afghan forces. Heavy violence continues as the Taliban step up their attacks on Afghan and U.S. forces and civilians, and take over more territory. At the same time, an Afghan ISIS branch also emerges.

Taliban members and Afghan officials meet informally in Qatar and agree to continue peace talks.

The Taliban make publicly known that Mullah Omar, the group's founder, died years earlier. Mullah Akhtar Mansour is named as the new leader. He is killed the following year in a U.S. drone attack in Pakistan.

The Afghan government grants immunity to former mujahideen leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar , known in the civil war years as the "butcher of Kabul."

Fighting continues between government forces and the Taliban, and attacks attributed to the Taliban and ISIS convulse the country.

The U.S. endgame

President Donald Trump appoints former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad as his special representative to negotiate with the Taliban.

After another disputed election in 2019, Ghani is declared president and Abdullah as head of the government's peace negotiating committee in early 2020.

Violence increases in Kabul. ISIS claims responsibility for some attacks, while others are never claimed. Journalists and rights activists are assassinated. Other targets include a maternity hospital and a girls' school.

U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad and Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar shake hands after signing the U.S.-Taliban peace agreement in Doha, Qatar, on Feb. 29, 2020. Karim Jaafar/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad and Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar shake hands after signing the U.S.-Taliban peace agreement in Doha, Qatar, on Feb. 29, 2020.

The U.S. and the Taliban sign a peace agreement in Doha, Qatar, on Feb. 29. The two sides agree on terms including for the U.S. withdrawal of troops and the Taliban to stop attacks on Americans.

Direct Taliban-Afghan government negotiations begin in Doha in September, but quickly stall and never resume in a serious way.

April 14, 2021

President Biden announces the withdrawal of remaining U.S. troops by Sept. 11.

President Joe Biden walks through Arlington National Cemetery in April to honor fallen veterans of the Afghan conflict. Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

President Joe Biden walks through Arlington National Cemetery in April to honor fallen veterans of the Afghan conflict.

The Taliban begin gaining territory in the north.

An Afghan National Army soldier stands on a Humvee at Bagram Air Base after all U.S. and NATO troops left, in July. Zakeria Hashimi/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

An Afghan National Army soldier stands on a Humvee at Bagram Air Base after all U.S. and NATO troops left, in July.

U.S. troops leave the Bagram Airfield, the key hub for the American war.

August 2021

The Taliban seize control of key cities and provinces, often without a fight. Within days, the only major city not under their control is Kabul.

Ghani flees, the government collapses and the capital comes under Taliban control on Aug. 15. Chaos erupts at the Kabul airport as desperate Afghans try to leave the country.

At a press conference on Aug. 17, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid promises an inclusive government, security for aid agencies and embassies and women's rights to work and go to school — within his group's interpretation of sharia law.

Taliban fighters take control of Afghanistan's presidential palace after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country on Sunday. Zabi Karimi/AP hide caption

Taliban fighters take control of Afghanistan's presidential palace after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country on Sunday.

A suicide bombing takes place on Aug. 26 outside Kabul's international airport as the chaotic evacuation of tens of thousands of Afghans, Americans and others continues. The attack, claimed by the Islamic State's Afghan affiliate, known as ISIS-K, kills nearly 200 Afghans and 13 U.S. service members.

On Aug. 29, the U.S. carries out its second drone strike on suspected ISIS-K suicide bombers since the airport attack. An Afghan family says 10 relatives, including children, were killed in the strike. The Pentagon is investigating.

On Aug. 30, U.S. Central Command Gen. Frank McKenzie announces the last planes have departed, marking the end of the military evacuation effort — and America's war in Afghanistan. The Taliban celebrate what they call "full independence." And for many Afghans — especially those wanting but unable to leave the country — a new era of painful uncertainty begins.

- Afghanistan

- Australia edition

- International edition

- Europe edition

The Afghanistan Papers review: superb exposé of a war built on lies

Craig Whitlock of the Washington Post used freedom of information to produce the definitive US version of the war

I n the summer of 2009, the latest in a long line of US military commanders in Afghanistan commissioned the latest in a long line of strategic reviews, in the perennial hope it would make enough of a difference to allow the Americans to go home.

There was some excitement in Washington about the author, Gen Stanley McChrystal, a special forces soldier who cultivated the image of a warrior-monk while hunting down insurgents in Iraq.

Hired by Barack Obama , McChrystal produced a 66-page rethink of the Afghan campaign, calling for a “properly resourced” counter-insurgency with a lot more money and troops.

It quickly became clear there were two significant problems. Al-Qaida, the original justification for the Afghan invasion, was not even mentioned in McChrystal’s first draft. And the US could not agree with its Nato allies on whether to call it a war or a peacekeeping or training mission, an issue with important legal implications.

In the second draft, al-Qaida was included and the conflict was hazily defined as “not a war in the conventional sense”. But no amount of editing could disguise the fact that after eight years of bloody struggle, the US and its allies were unclear on what they were doing and who they were fighting.

The story is one of many gobsmacking anecdotes and tragic absurdities uncovered by Craig Whitlock, an investigative reporter at the Washington Post. His book is based on documents obtained through freedom of information requests, most from “lessons learned” interviews conducted by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (Sigar), a watchdog mandated by Congress to keep tabs on the hundreds of billions flowing into Afghanistan.

In the Sigar files, and other interviews carried out by military institutes and research centres, Whitlock found that soldiers of all ranks and their civilian counterparts were “more open about their experiences than they likely would have been with a journalist working on a news story”.

Blunt appraisals were left unvarnished because they were never intended for publication. The contrast with the upbeat version of events presented to the public at the same time, often by the very same people, is breathtaking.

The Afghanistan Papers is a book about failure and about lying about failure, and about how that led to yet worse failures, and so on for 20 years. The title and the contents echo the Pentagon Papers, the leaked inside story of the Vietnam war in which the long road to defeat was paved with brittle happy talk.

“With their complicit silence, military and political leaders avoided accountability and dodged reappraisals that could have changed the outcome or shortened the conflict,” Whitlock writes. “Instead, they chose to bury their mistakes and let the war drift.”

As Whitlock vividly demonstrates, the lack of clarity, the deception, ignorance and hubris were baked in from the beginning. When he went to war in Afghanistan in October 2001, George Bush promised a carefully defined mission. In fact, at the time the first bombs were being dropped, guidance from the Pentagon was hazy.

It was unclear, for example, whether the Taliban were to be ousted or punished.

“We received some general guidance like, ‘Hey, we want to go fight the Taliban and al-Qaida in Afghanistan,’” a special forces operations planner recalled. Regime change was only decided to be a war aim nine days after the shooting started.

The US was also hazy about whom they were fighting, which Whitlock calls “a fundamental blunder from which it would never recover”.

Most importantly, the invaders lumped the Taliban in with al-Qaida, despite the fact the former was a homegrown group with largely local preoccupations while the latter was primarily an Arab network with global ambitions.

That perception, combined with unexpectedly easy victories in the first months, led Bush’s defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld , to believe the Taliban could be ignored. Despite offers from some leaders that they were ready to negotiate a surrender, they were excluded from talks in December 2001 on the country’s future. It was a decision the United Nations envoy, Lakhdar Brahimi, called the “original sin” of the war.

Rumsfeld declared there was no point negotiating.

“The only thing you can do is to bomb them and try to kill them,” he said in March 2002. “And that’s what we did, and it worked. They’re gone.”

Not even Rumsfeld believed that. In one of his famous “snowflake” memos, at about the same time, he wrote: “I am getting concerned that it is drifting.”

In a subsequent snowflake, two years after the war started, he admitted: “I have no visibility into who the bad guys are.”’

The Taliban had not disappeared, though much of the leadership had retreated to Pakistan. The fighters had gone home, if necessary to await the next fighting season. Their harsh brand of Islam had grown in remote, impoverished villages, honed by the brutalities of Soviet occupation and civil war. The Taliban did not represent anything like a majority of Afghans, but as their resilience and eventual victory have shown, they are an indelible part of Afghanistan.

Whitlock’s book is rooted in a database most journalists and historians could only dream of, but it is far more than the sum of its sources. You never feel the weight of the underlying documents because they are so deftly handed. Whitlock uses them as raw material to weave anecdotes into a compelling narrative.

He does not tell the full story of the Afghan war. He does not claim to do so. That has to be told primarily by Afghans, who lived through the realities submerged by official narratives, at the receiving end of each new strategy and initiative.

This is a definitive version of the war seen through American eyes, told by Americans unaware their words would appear in public. It is a cautionary tale of how a war can go on for years, long after it stops making any kind of sense.

- Afghanistan

- South and central Asia

- US military

- US foreign policy

- US national security

- George Bush

Most viewed

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Afghanistan War

By: History.com Editors

Published: August 20, 2021

The United States launched the war in Afghanistan following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The conflict lasted two decades and spanned four U.S. presidencies, becoming the longest war in American history.

By August 2021, the war began to come to a close with the Taliban regaining power two weeks before the United States was set to withdraw all troops from the region. Overall, the conflict resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and a $2 trillion price tag . Here's a look at key events from the conflict.

War on Terror Begins

Investigators determined the 9/11 attacks—in which terrorists hijacked four commercial airplanes, crashing two into the World Trade Center towers in New York City , one at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., and one in a Pennsylvania field —were orchestrated by terrorists working from Afghanistan, which was under the control of the Taliban, an extremist Islamic movement. Leading the plot that killed more than 2,700 people was Osama bin Laden , leader of the Islamic militant group al Qaeda . It was believed the Taliban, which seized power in the country in 1996 following an occupation by the Soviet Union , was harboring bin Laden, a Saudi, in Afghanistan.

In an address on September 20, 2001, President George W. Bush demanded the Taliban deliver bin Laden and other al Qaeda leaders to the United States, or "share in their fate." They refused.

On October 7, 2001, U.S. and British forces launched Operation Enduring Freedom , an airstrike campaign against al Qaeda and Taliban targets including Kandahar, Kabul and Jalalabad that lasted five days. Ground forces followed, and with the help of Northern Alliance forces, the United States quickly overtook Taliban strongholds, including the capital city of Kabul, by mid-November. On December 6, Kandahar fell, signaling the official end of Taliban rule in Afghanistan and causing al Qaeda, and bin Laden, to flee.

Shift to Reconstruction

During a speech on April 17, 2002, Bush called for a Marshall Plan to aid in Afghanistan’s reconstruction, with Congress appropriating more than $38 billion for humanitarian efforts and to train Afghan security forces. In June, Hamid Karzai, head of the Popalzai Durrani tribe, was chosen to lead the transitional government.

While approximately 8,000 American troops remained in Afghanistan as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) overseen by NATO, the U.S. military focus turned to Iraq in 2003, the same year U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld declared "major combat" operations had come to an end in Afghanistan.

A new constitution was soon enacted and Afghanistan held its first democratic elections since the onset of the war on October 9, 2004, with Karzai, who went on to serve two five-year terms, winning the vote for president. The ISAF’s focus shifted to peacekeeping and reconstruction, but with the United States fighting a war in Iraq, the Taliban regrouped and attacks escalated.

Troop Surge Under Obama

In a written statement released February 17, 2009, newly elected President Barack Obama pledged to send an extra 17,000 U.S. troops to Afghanistan by summer to join 36,000 American and 32,000 NATO forces already deployed there. "This increase is necessary to stabilize a deteriorating situation in Afghanistan, which has not received the strategic attention, direction and resources it urgently requires," he stated . American troops reached a peak of approximately 110,000 soldiers in Afghanistan in 2011.

In November 2010, NATO countries agreed to a transition of power to local Afghan security forces by the end of 2014, and, on May 2, 2011, following 10-year manhunt, U.S. Navy SEALs located and killed bin Laden in Pakistan.

Following bin Laden's death, a decade into the war and facing calls from both lawmakers and the public to end the war, Obama released a plan to withdraw 33,000 U.S. troops by summer 2012, and all troops by 2014. NATO transitioned control to Afghan forces in June 2013, and Obama announced a new timeline for troop withdrawal in 2014, which included 9,800 U.S. soldiers remaining in Afghanistan to continue training local forces.

Trump: 'We Will Fight to Win'

In 2015, the Taliban continued to increase its attacks, bombing the parliament building and airport in Kabul and carrying out multiple suicide bombings.

In his first few months of office, President Donald Trump authorized the Pentagon to make combat decisions in Afghanistan, and, on April 13, 2017, the United States dropped its most powerful non-nuclear bomb, called the " mother of all bombs ," on a remote ISIS cave complex.

In August 2017, Trump delivered a speech to American troops vowing " we will fight to win " in Afghanistan. "America's enemies must never know our plans, or believe they can wait us out," he said. "I will not say when we are going to attack, but attack we will."

The Taliban continued to escalate its terrorist attacks, and the United States entered peace talks with the group in February 2019. A deal was reached that included the U.S. and NATO allies pledging a total withdrawal within 14 months if the Taliban vowed to not harbor terrorist groups. But by September, Trump called off the talks after a Taliban attack that left a U.S. soldier and 11 others dead. “If they cannot agree to a ceasefire during these very important peace talks, and would even kill 12 innocent people, then they probably don’t have the power to negotiate a meaningful agreement anyway,” Trump tweeted .

Still, the United States and Taliban signed a peace agreement on February 29, 2020, although Taliban attacks against Afghan forces continued, as did American airstrikes. In September 2020, members of the Afghan government met with the Taliban to resume peace talks and in November Trump announced that he planned to reduce U.S. troops in Afghanistan to 2,500 by January 15, 2021.

Withdrawal of US Troops

The fourth president in power during the war, President Joe Biden , in April 2021, set the symbolic deadline of September 11, 2021, the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, as the date of full U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, with the final withdrawal effort beginning in May.

Facing little resistance, in just 10 days, from August 6-15, 2021, the Taliban swiftly overtook provincial capitals, Kandahar, Mazar-e-Sharif and, finally, Kabul. As the Afghan government collapsed, President Ashraf Ghani fled to the UAE , the U.S. embassy was evacuated and thousands of citizens rushed to the airport in Kabul to leave the country.

By August 14, Biden had temporarily deployed about 6,000 U.S. troops to assist in evacuation efforts. Facing scrutiny for the Taliban's swift return to power, Biden stated , “I was the fourth president to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan—two Republicans, two Democrats. I would not, and will not, pass this war on to a fifth.”

During the war in Afghanistan, more than 3,500 allied soldiers were killed, including 2,448 American service members, with 20,000-plus Americans injured. Brown University research shows approximately 69,000 Afghan security forces were killed, along with 51,000 civilians and 51,000 militants. According to the United Nations, some 5 million Afghanis have been displaced by the war since 2012, making Afghanistan the world's third-largest displaced population .

The U.S. War in Afghanistan , Council on Foreign Relations

Costs of the Afghanistan war, in lives and dollars , Associated Press

Who Are the Taliban, and What Do They Want? , The New York Times

Operation Enduring Freedom Fast Facts , CNN

Afghanistan: Why is there a war? , BBC News

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Incredible History of Afghanistan

Kanishk tharoor on the country's rich story at the crossroads of asia.

By Google Arts & Culture

Words by Kanishk Tharoor

By James Burke LIFE Photo Collection

Afghanistan often appears in the Western imagination as a barren, arid land, a forbidding “graveyard of empires.” This perception does not do justice to its cosmopolitan history as a crossroads between South Asia and Central Asia, both its settled and nomadic peoples, and its rich traditions of Zoroastrianism, Hellenism, Buddhism, and Islam.

Group of Five Vessels (1st century B.C.) by Unknown The J. Paul Getty Museum

The ancient city of Balkh in what is now northern Afghanistan sat along one of the routes of the Silk Road. Balkh was one of the great trading posts of the region and served as a political and religious center for millennia. According to some sources, it was from Balkh that the prophet Zoroaster first preached the religion that would become Zoroastrianism, the official faith of several Persian dynasties.

Bronze coin of Agathocles (-190/-180) British Museum

Bactria - the wider region around Balkh - came under Persian rule as a satrapy, or province, of the Achaemenid empire and then centuries later under the rule of the Parthian and Sassanian dynasties. In between, it was among the conquests of Alexander the Great, who left an indelible mark on the territory and its culture.

Four Scenes from the Life of Buddha - (Detail) The Enlightenment (0180/0320) Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art

Hellenic culture took root in the region, with the Greek language, script, and iconography in frequent use, including on the coins of Greco-Bactrian rulers. The coins of Agothocles (who ruled in the 2nd century BCE) mingled Greek and South Asian imagery and writing, placing Buddhist and Hindu figures on the front of many coins. This fusion of cultures spread southeast to Gandhara, the historic region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Standing bodhisattva (3rd?4th century) by Gandharan region, Afghanistan or Pakistan National Gallery of Australia

Invaders came to the area not just from the west, but also from the east. The Indian dynasty known as the Mauryas wrestled with the Greek successors of Alexander the Great for control over Afghanistan in the late 4th century. Later, a Mauryan ruler, Ashoka, adopted Buddhism and encouraged its practice across the realm. Archaeologists in the 1960s found one of the king’s rock edicts written in Greek - a nod to the remaining Greek communities in the region - near Kandahar in the south of Afghanistan as well as a multilingual rock inscription in Greek and Aramaic. The Ashoka Greek edict was taken to the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul from where it was stolen in the turmoil of the early 1990s.

Bamiyan Buddha Before and After CyArk

In later centuries, Gandhara became the centre of the distinctive sculptural tradition of rendering the Buddha and other Buddhist figures in human form. Greek and South Asian traditions of representation merge together in the carving of these characteristically graceful (and often mustachioed) sculptures.

Double dirham of Nuh b. Mansur (976/997) British Museum

Afghanistan was part of the trade route between South Asia and Central Asia. Buddhist texts would journey through the region along the Silk Road to the great translation centers of the Taklamakan desert before eventually reaching China and spreading the religion there. Buddhist foundations and monasteries flourished, resulting in the construction of the gargantuan Bamiyan buddhas in the 6th century. The puritanical Taliban destroyed these buddhas in 2001, a desecration that sparked outrage around the world.

Bowl Bowl Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Islam arrived in the region in the 7th century after the swift Arab advance through the remnants of the Persian Sassanian empire. Itwould become the dominant faith in the region and is now followed by over 99% of Afghans. A succession of Muslim dynasties grappled over the region, especially after rich deposits of silver were discovered in the Hindu Kush in the 9th and 10th centuries and caused something of a frenzied “silver rush” akin to the gold rush in the American west. These silver dirhams above were minted under the Samanid dynasty, whose patronage of the arts saw the development of an Islamic and Persian-language culture –often described as “Persianate” culture” –that would spread as far as South Asia and the Mediterranean.

Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) by Amir Khusraw Dihlavi (d. 1325); The abduction by sea (1496) by Artist: Attributed to Kamal al-Din Bihzad Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art

The city of Herat in western Afghanistan was a major trading centre, famous for its intellectuals, poets, artisans, and painters. The poet Rumi described Herat as “the pearl of Khorasan” and “the pleasantest of cities.” After being razed to the ground by Genghis Khan’s Mongol army in the 13th century, it recovered to enjoy a golden period of political and cultural prominence under the Timurid dynasty until the 16th century.

In this painting from a Timurid-era manuscript composed in Herat, a king’s female attendant is abducted by her lover. The scene comes from the famous Khamsa or “quintet” of the Indian poet Amir Khusraw Dilhavi, a testament of the sweeping ties that bound Herat to the wider Persianate world.

Documenting the Australians in Afghanistan (2009) Australian War Memorial

Herat remains a bustling city, but it has suffered in recent times like the rest of the country. For the last four decades, Afghanistan has been wracked by war. The Soviet invasion of the country in 1979 triggered a series of ongoing conflicts. Hundreds of thousands of Afghans have died and over six million have become refugees. The photo above is of Kabul in1963, before the capital city would be devastated in the wars to come.

Invariably, the violence has also battered the cultural heritage of Afghanistan. After a bombing in 1993 and subsequent looting, the National Museum of Afghanistan lost nearly 70% of its collection. In the midst of the chaos, the puritanical Taliban came to power in 1996 and issued an edict five years later against pre-Islamic statues and objects. The American invasion in 2001 led to continued war and instability, which saw the further wrecking of historic neighborhoods of cities like Kabul, threats and damage to important cultural sites, and the illegal trafficking of antiquities out of the country. Speaking in 2010, the French archaeologist Philippe Marquis grimly told AFP that “there is absolutely no site in this country which is unaffected.”

Explore more: – Repairing Heritage In Conflict Zones

Australian War Memorial

A brief history of the peacock room, smithsonian's national museum of asian art, cyark's story, joseph: a celebrated haitian model in 19th-century paris, the j. paul getty museum, reigning men: fashion in menswear, 1715 - 2015, los angeles county museum of art, a journey: conserving the atlas of joseph russegger’s seminal publication reisen in europa, asien und africa etc. (1842-1849), british museum, "g for george", arts of the indian subcontinent and the himalayas, a journey along the qhapaq ñan, irises at the getty, the ballcourts of chichén itzá.

JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY 111

4 th Quarter, October 2023

ESSAY COMPETITIONS

SPECIAL FEATURE

BOOK REVIEWS

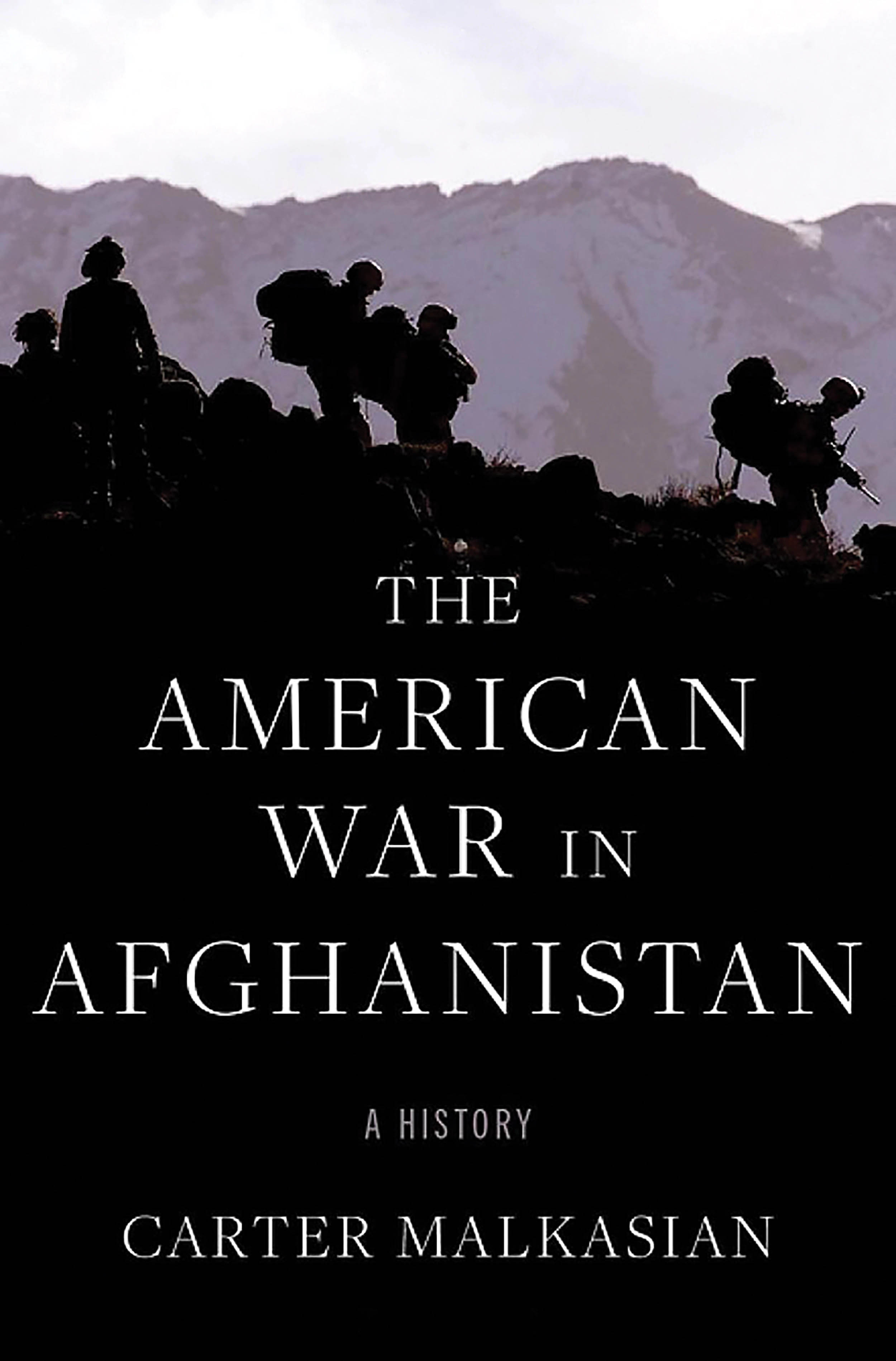

The American War in Afghanistan: A History

By Kevin D. Stringer Joint Force Quarterly 111

Download PDF

The American War in Afghanistan: A History By Carter Malkasian New York: Oxford University Press, 2021 496 pp. $34.95 ISBN: 9780197550779 Reviewed by Kevin D. Stringer

C arter Malkasian provides a magisterial and balanced account of the American intervention in Afghanistan from 2001 until the early months of 2021. His writing, analysis, and credibility are buttressed by his multiple deployments to the country at both the provincial and district levels as well as by his fluency in Pashto. His roles as senior advisor to the military commander in Afghanistan and later to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff further enhance his insights. Since the topic can be approached from a myriad of perspectives, Malkasian’s book is likely the first in a long series of historical examinations over the next several decades. His book can serve as the flagship for those who follow, given its comprehensiveness and lucidity. While lessons for future conflicts are abundant, The American War in Afghanistan illuminates three critical areas for understanding U.S. operations and errors in Afghanistan: improper cultural understanding of Afghanistan and the region, avoidable national security policy mistakes, and blunders in decisionmaking by senior leaders.

Malkasian adroitly demonstrates how successive U.S. administrations and their military and civilian leaders failed to understand that the Taliban most represented the Afghan culture’s tribal core values, which centered on Islam and resistance to any foreign occupier. This cultural dimension made any Western-supported government suspect. The American tendency to conflate the Taliban with al Qaeda, especially in the period of 2001–2005, compounded this lack of comprehension and resulted in the exclusion of the Taliban in a post-invasion agreement. This exclusion closed what was probably the best chance for an orderly withdrawal after the great 2001 success in what would become an extended conflict. At the regional level, an inability to understand and address Pakistan’s historical, cultural, and geopolitical position in a nuanced fashion resulted in creating a permanent sanctuary for the Taliban outside of Afghanistan and a state provider of security force assistance for the Taliban’s resistance fighters within Afghanistan.

Similarly, the author reflects on and examines a continuous sequence of avoidable national security policy mistakes—avoidable in the sense that the correct policy decisions would have required the courage to confront skeptical domestic and bureaucratic constituencies. Two major examples illustrate these miscalculations. First, the unwillingness to engage in a firm but direct diplomacy with the Taliban closed opportunities to reach a negotiated settlement under the Bush and Obama administrations. Second, President Barack Obama’s restrictive policy on airstrikes from 2014–2015 led to a series of Afghan government defeats, resulting in a downward spiral in morale for the Afghan military that echoed into 2021. Malkasian illustrates this misplaced policy when he notes how Obama White House staff “often asked why the Afghan army needed air support when the Taliban so clearly did not.” This approach cost the Afghan military dearly in both blood and spirit.

Finally, the author stresses the importance of human agency. On the civilian side, although the decisionmaking of all four involved Presidents contributed to the 20-year imbroglio, the author demonstrates that President Obama oversaw the period with the greatest prospects for an acceptable solution. His missteps were unfortunately manifold. As noted, he failed to negotiate with the Taliban, he did not leverage the troop surge to its fullest, and his communication of a withdrawal deadline instead of relying on a conditions-based troop reduction allowed the Taliban to wait him out.

Interestingly, the author postulates that President Donald Trump had the political courage and will to open negotiations with the Taliban, which provided the only opportunity for a peace with honor. Sadly, President Trump’s impatient and erratic policymaking made for a less-than-satisfactory peace agreement. Insightfully, Malkasian notes that whereas the Bush and Obama administrations neglected to engage with the Taliban, the Trump White House negotiated a settlement without the Afghan government, thereby undercutting the legitimacy of the agreement. This method repeated that of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which ended the Vietnam War for the United States. The South Vietnamese government was also excluded and overrun by North Vietnam 2 years later.

On the military side, Malkasian critiques fewer of the military commanders but singles out a handful of notables for a closer examination. General Joseph Dunford, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, comes away as the most astute and prescient general of the war. Although Malkasian worked directly for Dunford, he provides a fair assessment of the general’s pragmatic approach to the Afghan conflict. Unerringly, General Dunford focused consistently on the main U.S. interest: “protecting the United States from terrorist attacks—with the minimum force.” In addition, Dunford studiously avoided the media, which resulted in his not running afoul of the White House. General Scott Miller, the former Joint Special Operations Command leader, who served multiple Afghan tours, receives merited accolades as the “most skilled general of the war.” His strategy adjustments to support negotiations, his “black cloud” operational approach (which combined a lethal package of special operations, drones, and intelligence assets to maximize pressure on the Taliban), and his preparation for withdrawal are worthy of future study for a campaign well-executed under trying circumstances.

This book is essential reading for all military officers, national security professionals, U.S. politicians, and relevant academics. While not the final assessment of the conflict, since it does not cover the Joe Biden administration’s disastrous withdrawal and evacuation of Afghanistan in August 2021, The American War in Afghanistan offers an academic-practitioner’s incisive account of the political and military aspects of America’s longest war. It provides numerous valuable lessons, not the least of which is a reminder of the human costs of such a foreign intervention. JFQ

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Suggestions for Kids

- Fiction Suggestions

- Nonfiction Suggestions

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Harvard Square Book Circle

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War

The groundbreaking investigative story of how three successive presidents and their military commanders deceived the public year after year about America’s longest war, foreshadowing the Taliban’s recapture of Afghanistan, by Washington Post reporter and three-time Pulitzer Prize finalist Craig Whitlock.

Unlike the wars in Vietnam and Iraq, the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 had near-unanimous public support. At first, the goals were straightforward and clear: to defeat al-Qaeda and prevent a repeat of 9/11. Yet soon after the United States and its allies removed the Taliban from power, the mission veered off course and US officials lost sight of their original objectives. Distracted by the war in Iraq, the US military became mired in an unwinnable guerrilla conflict in a country it did not understand. But no president wanted to admit failure, especially in a war that began as a just cause. Instead, the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations sent more and more troops to Afghanistan and repeatedly said they were making progress, even though they knew there was no realistic prospect for an outright victory. Just as the Pentagon Papers changed the public’s understanding of Vietnam, The Afghanistan Papers contains startling revelation after revelation from people who played a direct role in the war, from leaders in the White House and the Pentagon to soldiers and aid workers on the front lines. In unvarnished language, they admit that the US government’s strategies were a mess, that the nation-building project was a colossal failure, and that drugs and corruption gained a stranglehold over their allies in the Afghan government. All told, the account is based on interviews with more than 1,000 people who knew that the US government was presenting a distorted, and sometimes entirely fabricated, version of the facts on the ground. Documents unearthed by The Washington Post reveal that President Bush didn’t know the name of his Afghanistan war commander—and didn’t want to make time to meet with him. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld admitted he had “no visibility into who the bad guys are.” His successor, Robert Gates, said: “We didn’t know jack shit about al-Qaeda.” The Afghanistan Papers is a shocking account that will supercharge a long overdue reckoning over what went wrong and forever change the way the conflict is remembered.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

- Skip to content

- Skip to main menu

- Skip to more DW sites

Essay: Why the West failed to understand Afghanistan

How could the Afghan government collapse so quickly? That things were going wrong in Afghanistan had been obvious for a long time, yet the West preferred to look the other way, says Emran Feroz.

"It will probably be like last time. When they took Kabul overnight," Kabul resident Ahmad Jawed, 30, told me last Saturday. When the militant Islamist Taliban first captured the Afghan capital 25 years ago, Jawed was a young child. But he remembers that morning well. Suddenly the fighters were there, while the members of the mujahedeen government, who had been in-fighting for years, had fled. Now, almost 20 years after NATO first occupied the country, this scenario seemed likely to repeat itself, Jawed predicted: "The last few days have made it clear that they will be here soon."

Shortly thereafter, his fears were confirmed. After the Taliban had seized all major provincial capitals in a matter of days, they marched into Kabul on Sunday. Many members of the army and police abandoned their posts even before the insurgents entered the city. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani ,for his part, hastily fled the country with his entourage. His behavior was like that of a neo-colonial governor — that's just how he has been described in recent years, not only by the Taliban but by many Afghans who did not benefit from his corrupt state apparatus.

According to some reports, Ghani's men took bags of cash with them. Incidentally, it was Ghani who said a few years ago that he had no sympathy for Afghan refugees. They would only end up washing dishes in the West. After Ghani's flight, the Taliban captured the presidential palace and posed for pictures in front of his desk.

Why did Afghan forces fail to resist the Taliban?

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

One of the commanders said shortly afterwards during a press conference for the Qatari broadcaster Al Jazeera that he had been detained and tortured by the Americans for eight years in Guantanamo. A coincidence? Probably not. Instead, it was evident once more that the American "War on Terror" had radicalized scores of people in Afghanistan – and that many of them have not forgotten it to this day.

Only white US citizens allowed to board?

Events continued to unfold at a swift pace. Crowds flocked to Kabul airport, where American troops were busy evacuating their citizens. The chaos at the airport did not abate the next day. People tried to cling to the US plane as it took off and died in their last-ditch attempt to escape.

Meanwhile, US soldiers fired into the Afghan crowd. "A relative of mine was killed. He was a doctor," recounted Sangar Paykhar, a Dutch-Afghan journalist and podcaster, after the incident. The Afghan-American author and activist Nadia Hashemi claimed that Afghan-Americans were in some cases denied entry onto the plane. The reason: They were not white Americans.

The latest scenes in Kabul have underscored more plainly than ever that the Western mission in Afghanistan has failed. During his speech yesterday, US President Joe Biden , in the midst of withdrawing his military forces, did not spare a single word for all the Afghans who have been killed by the American "War on Terror" over the past two decades. Instead, his words were once again marked by a denial of reality and by ignorance. The true winners of the war are not in the White House but in Kabul.

20 years in Afghanistan – Was it worth it?

Us war equipment for the taliban.

The Taliban have never been as strong as they are now. In the last few days and weeks alone, they have captured numerous pieces of high-tech American war equipment.

Apart from Panjshir province north of Kabul, which has always been a stronghold of Taliban resistance, the extremists now once again control almost all of Afghanistan. And they have regained political clout on the international stage as well, something they have worked hard on in recent years.

Numerous analyses and forecasts concerning a Taliban takeover have had to be corrected several times in recent days. The US intelligence agency CIA was still assuming on Saturday that it would take 30 to 90 days to overpower Kabul. In the end, it all happened in 24 hours. Even prominent US analysts in Washington were at a loss for words in the face of recent events.

How was it possible?

Bill Roggio of the right-wing conservative US think tank "Foundation for the Defense of Democracies" called the Taliban's successful advance one of the "greatest intelligence failures in decades". Roggio described the Taliban's sophisticated war strategy as "brilliant." The extremists initially focused on the north of the country before taking additional cities nationwide.

There are several reasons why all this was possible. Much of what was going on in the country was suppressed and ignored for years – not only because people in the West wanted to save face but also because they still didn't know Afghanistan, even after all these years. Nearly all the districts of those provincial capitals that fell prior to Kabul had in fact been controlled by the Taliban for years.

The Taliban had put down roots there, operating and ruling in the shadows. That extremists were able to gain an early foothold in these rural regions is also due in part to the massive corruption in the capital and the numerous military operations carried out by NATO and its Afghan allies.

Victims of the West

Drone attacks and brutal nightly raids regularly caused numerous civilian casualties in Afghan villages. Many survivors shifted their support to the Taliban as a result. This was de facto also the case at the gates of Kabul. Long before the recent events, a 20- to 30-minute drive was enough to take you into Taliban territory.

Joe Biden: 'We're going to do everything in our power to get all Americans out and our allies out'

But those in charge did not want to face up to these realities. Instead, they were busy patting themselves on the back for a job well done. People spoke of their own oh-so-commendable values and focused on the supposed achievements made in Afghanistan since 2001. There was much talk of democracy, although not a single democratic transfer of power has taken place in Afghanistan in the last 20 years.

Corrupt elites

This certainly had nothing to do with those Afghans that risked their lives to go to the polls but can primarily be attributed to the corrupt elites that the US brought to power in Kabul. Men like Hamid Karzai and President Ashraf Ghani, who could not flee quickly enough, exploited the new system to their own ends and stayed in power through electoral fraud. Other important figures in Afghanistan behaved similarly, including numerous well-known warlords and drug barons who became the West's closest allies in the Hindu Kush. They were able to line their pockets with the generous foreign aid and transfer billions of dollars abroad.

At the same time, they were also among the biggest war profiteers – thanks, for example, to private security companies they themselves created to fake attacks on NATO troops. In retrospect, it is evident that lucrative contracts were signed based on the alleged terrorist threat.

No need to take responsibility

It has been clear at least since the end of 2019 that leaders in Washington and elsewhere knew all about these aberrations. Ever since the Washington Post published the "Afghanistan Papers," in which about 400 high-ranking US officials more or less admitted to their failures in Afghanistan. The details had been kept under wraps for years.

But nobody wants to talk about that today either. Instead, it is easy to get the impression that the Taliban have come out of nowhere to take Afghanistan and the West by storm. Everyone claims to have acted according to the best of their knowledge and with a clear conscience.

So, it is unfortunate, then, how things turned out. After 20 years of a misguided intervention that cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Afghans and turned millions of them into refugees, driving them into poverty, the West has not only lost interest in Afghanistan, but feels no need to take responsibility for its plight.

"These people are just like that. It's not our fault," is the tenor of this cultural relativism. It is echoing particularly loudly these days.

Emran Feroz is an Austrian with Afghan roots who has been reporting for years on the situation in the Hindu Kush for German-language media such as "Die Zeit," "taz, die tageszeitung" and "WOZ," but also US media such as the "New York Times" and CNN. At the beginning of October, his analysis "The Longest War - 20 Years of the War on Terror" should have been published on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the beginning of the so-called "War on Terror." Due to current events, this date was moved to August 23, 2021.

This text was originally published in German on www.qantara.de.

© Qantara.de 2021

Explore more

Related topics.

- Account and Profile

- Newsletters & Alerts

- Gift Subscriptions

- Home Page U.S. & World | Regional

- White House

- Courts and Law

- Monkey Cage

- Fact Checker

- Post Politics Blog

- The Post's View

- Toles Cartoons

- Telnaes Animations

- Local Opinions

- Global Opinions

- Letters to the Editor

- All Opinions Are Local

- Erik Wemple

- The Plum Line

- PostPartisan

- DemocracyPost

- The WorldPost

- High School Sports

- College Sports

- College Basketball

- College Football

- D.C. Sports Bog

- Fancy Stats

- Fantasy Sports

- Public Safety

- Transportation

- Acts of Faith

- Health and Science

- National Security

- Investigations

- Morning Mix

- Post Nation

- The Americas

- Asia and Pacific

- Middle East

- On Leadership

- Personal Finance

- Energy and Environment

- On Small Business

- Capital Business

- Innovations

- Arts and Entertainment

- Carolyn Hax

- Voraciously

- Home and Garden

- Inspired Life

- On Parenting

- Reliable Source

- The Intersect

- Comic Riffs

- Going Out Guide

- Puzzles and Games

- Theater and Dance

- Restaurants

- Bars & Clubs

- Made by History

- PostEverything

- Entertainment

- Popular Video

- Can He Do That?

- Capital Weather Gang

- Constitutional

- The Daily 202's Big Idea

- Letters From War

- Presidential

- Washington Post Live

- Where We Live

- Recently Sold Homes

- Classifieds

- WP BrandStudio

- washingtonpost.com

- 1996-2018 The Washington Post

- Policies and Standards

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Submissions and Discussion Policy

- RSS Terms of Service

Built to fail

Despite vows the u.s. wouldn’t get mired in ‘nation-building,’ it’s wasted billions doing just that.

Kabul, 2009 (David Guttenfelder/AP)

Kabul, 2005 (David Guttenfelder/AP)

Kabul, 2004 (Emilio Morenatti/AP)

George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump all promised the same thing: The United States would not get stuck with the burden of “nation-building” in Afghanistan.

In October 2001, shortly after ordering U.S. forces to invade, Bush said he would push the United Nations to “take over the so-called nation-building.”

Eight years later, Obama insisted his government would not get mired in a long “nation-building project,” either. Eight years after that, Trump made a similar vow: “We’re not nation-building again.”

More stories

The Afghanistan Papers

Part 3: Built to fail

Yet nation-building is exactly what the United States has tried to do in war-battered Afghanistan — on a colossal scale.

Since 2001, Washington has spent more on nation-building in Afghanistan than in any country ever, allocating $133 billion for reconstruction, aid programs and the Afghan security forces.

Adjusted for inflation, that is more than the United States spent in Western Europe with the Marshall Plan after World War II.

This series is the basis for a book, “The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War,” by Washington Post reporter Craig Whitlock. The book can be ordered here.

Unlike the Marshall Plan, however, the exorbitant nation-building project for Afghanistan went awry from the start and grew worse as the war dragged on, according to a trove of confidential government interviews with diplomats, military officials and aid workers who played a direct role in the conflict.

See the documents More than 2,000 pages of interviews and memos reveal a secret history of the war.

Part 4: Consumed by corruption How the United States allowed graft and thievery to thrive.

Responses to The Post from people named in The Afghanistan Papers

Instead of bringing stability and peace, they said, the United States inadvertently built a corrupt, dysfunctional Afghan government that remains dependent on U.S. military power for its survival. Assuming it does not collapse, U.S. officials have said it will need billions more dollars in aid annually, for decades.

Speaking candidly on the assumption that most of their remarks would not be made public, those interviewed said Washington foolishly tried to reinvent Afghanistan in its own image by imposing a centralized democracy and a free-market economy on an ancient, tribal society that was unsuited for either.

Then, they said, Congress and the White House made matters worse by drenching the destitute country with far more money than it could possibly absorb. The flood crested during Obama’s first term as president, as he escalated the number of U.S. troops in the war zone to 100,000.

Click any underlined text in the story to see the statement in the original document

Girls from the northeastern village of Ghumaipayan Mahnow watch U.N. workers unload ballots before the October 2004 presidential election. (Emilio Morenatti/AP)

Afghanistan’s first class of female army officers graduates in Kabul in 2010. (Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

Girls from the northeastern village of Ghumaipayan Mahnow watch U.N. workers unload ballots before the October 2004 presidential election. (Emilio Morenatti/AP) Afghanistan’s first class of female army officers graduates in Kabul in 2010. (Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

By some measures, life in Afghanistan has improved markedly since 2001. Infant mortality rates have dropped. The number of children in school has soared. The size of the Afghan economy has nearly quintupled.

But the U.S. nation-building project backfired in so many other ways that even foreign-aid advocates questioned whether Afghanistan, in the abstract, might have been better off without any U.S. help at all, according to the documents.

Callen and others blamed an array of mistakes committed again and again over 18 years — haphazard planning, misguided policies, bureaucratic feuding. Many said the overall nation-building strategy was further undermined by hubris, impatience, ignorance and a belief that money can fix anything.

Much of the money, they said, ended up in the pockets of overpriced contractors or corrupt Afghan officials, while U.S.-financed schools, clinics and roads fell into disrepair, if they were built at all.

Some said the outcome was foreseeable. They cited the U.S. track record of military interventions in other countries — Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Haiti, Somalia — over the past quarter-century.

Troubles plaguing many reconstruction programs in Afghanistan have been well documented, but the interview records obtained by The Washington Post contain new narratives from insiders on what went wrong.

AFGHANISTAN

TURKMENISTAN

In comments echoed by other officials who shaped the war, Lute said the United States lavished money on dams and highways just “to show we could spend it,” fully aware that the Afghans, among the poorest and least educated people in the world, could never maintain such huge infrastructure projects.

What they said in private Sept. 23, 2014

“We weren’t seriously into it — didn’t have our heart in it. We were pushed into state-building.”

— Senior State Department official, on the early years of the war, Lessons Learned interview

Ever since the war started, U.S. officials have debated — and decried — the expense of rebuilding Afghanistan. In 2008, as reports of fraud and excessive spending piled up, Congress created a watchdog agency to follow the money.

Since then, the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, or SIGAR, has carried out more than 1,000 audits and investigations, exposing wasteful projects and highlighting $2 billion in potential savings.

In 2014, SIGAR launched a special $11 million project — titled “Lessons Learned” — to diagnose policy failures in Afghanistan. Agency staffers interviewed more than 600 people with firsthand experience in the war.

SIGAR published two Lessons Learned reports that focused on nation-building, but they were steeped in jargon and omitted the most critical comments from the interviews.

“The U.S. government’s provision of direct financial support sometimes created dependent enterprises and disincentives for Afghans to borrow from market-based financial institutions,” concluded an April 2018 report on development of the Afghan private sector. “Furthermore, insufficient coordination within and between U.S. government civilian and military agencies often negatively affected the outcomes of programs.”

In one of the hundreds of Lessons Learned interviews obtained by The Post, Robert Finn, who served as U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan from 2002 to 2003, said Bush administration officials dismissed his early warnings that they needed to do far more to stabilize Afghanistan.

Of the three commanders in chief, Bush may have been the unlikeliest nation-builder. When he first campaigned for the presidency, he derided the Clinton administration for committing to unpopular “nation-building exercises” in Somalia and Haiti.

“I don’t think our troops ought to be used for what’s called nation-building,” he said during a debate with Democratic nominee Al Gore in October 2000. “I think our troops ought to be used to fight and win war.”

A year later, Bush ordered U.S. forces to invade Afghanistan. Victory on the battlefield came swiftly. Coping with the aftermath would take longer than most expected.

No nation needed more building than Afghanistan. Desperately poor, it had been consumed by continuous warfare since 1979, when it was invaded by another superpower, the Soviet Union.

Few Afghans knew much about the outside world. A large majority were illiterate. The country’s ousted rulers, the Taliban, a movement of religious zealots, had banned many hallmarks of modern civilization, including television, musical instruments and equal rights for women.

Boys play soccer in 2005 in an empty and war-damaged Soviet-era pool in Kabul. (David Guttenfelder/AP)

Mindful of Bush’s campaign rhetoric, his administration initially tried to avoid responsibility for Afghanistan’s reconstruction, according to people interviewed for the Lessons Learned project.

The administration tried to get the United Nations, NATO and other countries to take charge of humanitarian aid and reconstruction. The United States agreed to help train a new Afghan army but pushed to keep it small, because the Pentagon and State Department did not want to bear the long-term costs.

Eventually, however, officials interviewed for the Lessons Learned project said, the Bush administration recognized it had a duty to help Afghanistan build a new economy from scratch. Although Afghanistan had scant experience with free markets, the United States pressured the Afghans to adopt American-style capitalism.

Yet several U.S. officials told government interviewers it quickly became apparent that people who would make up the Afghan ruling class were too set in their ways to change.

When it came to economics, others said the United States too often treated Afghanistan like a theoretical case study and should have applied more common sense instead.

Donors insisted that a large portion of aid be spent on education, even though Afghanistan — a nation of subsistence farmers — had few jobs for graduates.

Students in Jalalabad, in eastern Afghanistan, in 2012. (Mikhail Galustov for The Washington Post)

U.S. and European officials also insisted that Afghanistan embrace free trade, even though it had almost nothing of value to export.

Economic policies that might have helped Afghanistan slowly emerge from penury, such as price controls and government subsidies, were not considered by U.S. officials who saw them as incompatible with capitalism, said Barnett Rubin, a former adviser to the United Nations and State Department.

What they said in private July 22, 2015

“The worst thing you can do is apply lessons from one country to another.”

— Peter Galbraith, former U.S. and U.N. diplomat, Lessons Learned interview

It didn’t take an Ivy League political scientist to see that Afghanistan needed a better system of government. Riven by feuding tribes and implacable warlords, the country had a volatile history of coups, assassinations and civil wars.

The Bush administration persuaded the Afghans to adopt a made-in-America solution — a constitutional democracy under a president elected by popular vote.

In many ways, the new government resembled a Third World version of Washington. Power was concentrated in the capital, Kabul. A federal bureaucracy sprouted in all directions, cultivated by dollars and legions of Western advisers.

Under American tutelage, Afghan officials were exposed to newfangled concepts and tools: PowerPoint presentations, mission statements, stakeholder meetings, even appointment calendars.

(Video by Joyce Lee/The Washington Post)

But there were fateful differences.

Under the new constitution, the Afghan president wielded far greater authority than the other two branches of government — the parliament and judiciary — and also got to appoint all the provincial governors. In short, power was centralized in the hands of one man.

The rigid, U.S.-designed system conflicted with Afghan tradition, typified by a mix of decentralized power and tribal customs. But with Afghanistan beaten down and broke, the Americans called the shots.

A big reason is that U.S. leaders had a potential Afghan ruler in mind. Hamid Karzai, a tribal leader from southern Afghanistan, belonged to the country’s largest ethnic group, the Pashtuns.

Perhaps more importantly, Karzai spoke polished English and was a CIA asset. In 2001, a U.S. spy had saved his life, and the CIA would keep Karzai on its payroll f or years to come.

Ceremonial guards at the presidential palace in Kabul in 2014. (Joël van Houdt for The Washington Post)

President Hamid Karzai during a 2014 interview with The Washington Post in Kabul. (Joël van Houdt for The Washington Post)

Ceremonial guards at the presidential palace in Kabul in 2014. (Joël van Houdt for The Washington Post) President Hamid Karzai during a 2014 interview with The Washington Post in Kabul. (Joël van Houdt for The Washington Post)

At first, to American eyes, the new system of government led by Karzai worked. In 2004, after serving as interim leader, Karzai was elected president in Afghanistan’s first national democratic election. He built a personal rapport with Bush; the two leaders chatted frequently by videoconference.

But relations gradually soured. Karzai grew outspoken and criticized the U.S. military for a surge of airstrikes and night raids that inflicted civilian casualties and alienated much of the population. Meanwhile, U.S. officials chafed as Karzai cut deals with warlords and doled out governorships as political spoils.

From left, USAID official James Bever, Karzai, Afghan Foreign Minister Abdullah Abdullah and U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad go over maps of road construction projects at a 2004 meeting in Kabul. (Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images)

In 2009, Karzai won reelection, narrowly avoiding a runoff thanks to a massive ballot-box stuffing campaign that tainted the outcome. Many U.S. officials were appalled and pressed for an independent investigation. Karzai, in turn, privately accused the Obama administration of violating Afghan sovereignty and plotting to oust him from power.

In the end, U.S. officials swallowed their objections. After all, they had built the new nation and put Karzai in charge.

What they said in private Oct. 7, 2016

“There was a crazy amount of pressure to spend money.”

— USAID official, Lessons Learned interview

A few weeks after Karzai’s reelection, Obama announced he would send 30,000 more U.S. troops to the war zone as part of a new strategy to defeat the Taliban and bolster the Afghan state.

In a December 2009 speech at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., Obama told Americans this would not mean a drawn-out extension of the nation-building campaign that had already dragged on for eight years.

“Some call for a more dramatic and open-ended escalation of our war effort, one that would commit us to a nation-building project of up to a decade. I reject this course,” Obama said. “Our troop commitment in Afghanistan cannot be open-ended, because the nation that I’m most interested in building is our own.”

Obama’s generals, however, held no illusions.

During a June 2010 hearing on Capitol Hill, Army Gen. David H. Petraeus was asked point-blank by skeptical lawmakers whether the United States was nation-building in Afghanistan.

“I made the decision to go ahead with it, but I was sure it was never going to work. The biggest lesson learned for me is, don’t do major infrastructure projects.”

— Ryan Crocker, the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan at the time Listen

“We are indeed,” said Petraeus, who at the time was the chief of the U.S. Central Command. “I’m just not going to evade it and play rhetorical games.”

In fact, a cornerstone of Obama’s counterinsurgency strategy was to build the Afghan government at breakneck speed — with unprecedented sums from the U.S. treasury.

Petraeus and other U.S. commanders were betting the Afghan people would choke off support for the Taliban if they felt Karzai’s government could protect them and deliver basic services.

But there were two big hurdles.

First, there was not much time for the counterinsurgency strategy to work. Obama had given the Pentagon just 18 months to turn the tide of the war before he wanted to start bringing troops home.

Second, across much of Afghanistan, there was hardly any government presence to begin with. And where there was, it was often corrupt and hated by the locals.

As a result, the Obama administration ordered the military, the State Department, USAID and their contractors to build up the Afghan government as quickly as possible. In the field, soldiers and aid workers were given a virtual blank check to construct schools, hospitals, roads — anything that might win loyalty from the populace.

Road maintenance workers in Kabul in 2013. (Lorenzo Tugnoli for The Washington Post)

In a Lessons Learned interview, Petraeus acknowledged the spendthrift strategy. But he said the U.S. military had no choice given Obama’s order to start reversing the surge in 2011.

What they said in private Jan. 22, 2016

“We were building roads to nowhere. . . . With what we spent, Afghanistan should look like Germany in 1955.”