- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

- What is a Systematic Review?

Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

- 2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

Review Typologies

There are many types of evidence synthesis projects, including systematic reviews as well as others. The selection of review type is wholly dependent on the research question. Not all research questions are well-suited for systematic reviews.

- Review Typologies (from LITR-EX) This site explores different review methodologies such as, systematic, scoping, realist, narrative, state of the art, meta-ethnography, critical, and integrative reviews. The LITR-EX site has a health professions education focus, but the advice and information is widely applicable.

Review the table to peruse review types and associated methodologies. Librarians can also help your team determine which review type might be appropriate for your project.

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91-108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review?

- Next: Manuals and Reporting Guidelines >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 8:22 PM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

How to Write Critical Reviews

When you are asked to write a critical review of a book or article, you will need to identify, summarize, and evaluate the ideas and information the author has presented. In other words, you will be examining another person’s thoughts on a topic from your point of view.

Your stand must go beyond your “gut reaction” to the work and be based on your knowledge (readings, lecture, experience) of the topic as well as on factors such as criteria stated in your assignment or discussed by you and your instructor.

Make your stand clear at the beginning of your review, in your evaluations of specific parts, and in your concluding commentary.

Remember that your goal should be to make a few key points about the book or article, not to discuss everything the author writes.

Understanding the Assignment

To write a good critical review, you will have to engage in the mental processes of analyzing (taking apart) the work–deciding what its major components are and determining how these parts (i.e., paragraphs, sections, or chapters) contribute to the work as a whole.

Analyzing the work will help you focus on how and why the author makes certain points and prevent you from merely summarizing what the author says. Assuming the role of an analytical reader will also help you to determine whether or not the author fulfills the stated purpose of the book or article and enhances your understanding or knowledge of a particular topic.

Be sure to read your assignment thoroughly before you read the article or book. Your instructor may have included specific guidelines for you to follow. Keeping these guidelines in mind as you read the article or book can really help you write your paper!

Also, note where the work connects with what you’ve studied in the course. You can make the most efficient use of your reading and notetaking time if you are an active reader; that is, keep relevant questions in mind and jot down page numbers as well as your responses to ideas that appear to be significant as you read.

Please note: The length of your introduction and overview, the number of points you choose to review, and the length of your conclusion should be proportionate to the page limit stated in your assignment and should reflect the complexity of the material being reviewed as well as the expectations of your reader.

Write the introduction

Below are a few guidelines to help you write the introduction to your critical review.

Introduce your review appropriately

Begin your review with an introduction appropriate to your assignment.

If your assignment asks you to review only one book and not to use outside sources, your introduction will focus on identifying the author, the title, the main topic or issue presented in the book, and the author’s purpose in writing the book.

If your assignment asks you to review the book as it relates to issues or themes discussed in the course, or to review two or more books on the same topic, your introduction must also encompass those expectations.

Explain relationships

For example, before you can review two books on a topic, you must explain to your reader in your introduction how they are related to one another.

Within this shared context (or under this “umbrella”) you can then review comparable aspects of both books, pointing out where the authors agree and differ.

In other words, the more complicated your assignment is, the more your introduction must accomplish.

Finally, the introduction to a book review is always the place for you to establish your position as the reviewer (your thesis about the author’s thesis).

As you write, consider the following questions:

- Is the book a memoir, a treatise, a collection of facts, an extended argument, etc.? Is the article a documentary, a write-up of primary research, a position paper, etc.?

- Who is the author? What does the preface or foreword tell you about the author’s purpose, background, and credentials? What is the author’s approach to the topic (as a journalist? a historian? a researcher?)?

- What is the main topic or problem addressed? How does the work relate to a discipline, to a profession, to a particular audience, or to other works on the topic?

- What is your critical evaluation of the work (your thesis)? Why have you taken that position? What criteria are you basing your position on?

Provide an overview

In your introduction, you will also want to provide an overview. An overview supplies your reader with certain general information not appropriate for including in the introduction but necessary to understanding the body of the review.

Generally, an overview describes your book’s division into chapters, sections, or points of discussion. An overview may also include background information about the topic, about your stand, or about the criteria you will use for evaluation.

The overview and the introduction work together to provide a comprehensive beginning for (a “springboard” into) your review.

- What are the author’s basic premises? What issues are raised, or what themes emerge? What situation (i.e., racism on college campuses) provides a basis for the author’s assertions?

- How informed is my reader? What background information is relevant to the entire book and should be placed here rather than in a body paragraph?

Write the body

The body is the center of your paper, where you draw out your main arguments. Below are some guidelines to help you write it.

Organize using a logical plan

Organize the body of your review according to a logical plan. Here are two options:

- First, summarize, in a series of paragraphs, those major points from the book that you plan to discuss; incorporating each major point into a topic sentence for a paragraph is an effective organizational strategy. Second, discuss and evaluate these points in a following group of paragraphs. (There are two dangers lurking in this pattern–you may allot too many paragraphs to summary and too few to evaluation, or you may re-summarize too many points from the book in your evaluation section.)

- Alternatively, you can summarize and evaluate the major points you have chosen from the book in a point-by-point schema. That means you will discuss and evaluate point one within the same paragraph (or in several if the point is significant and warrants extended discussion) before you summarize and evaluate point two, point three, etc., moving in a logical sequence from point to point to point. Here again, it is effective to use the topic sentence of each paragraph to identify the point from the book that you plan to summarize or evaluate.

Questions to keep in mind as you write

With either organizational pattern, consider the following questions:

- What are the author’s most important points? How do these relate to one another? (Make relationships clear by using transitions: “In contrast,” an equally strong argument,” “moreover,” “a final conclusion,” etc.).

- What types of evidence or information does the author present to support his or her points? Is this evidence convincing, controversial, factual, one-sided, etc.? (Consider the use of primary historical material, case studies, narratives, recent scientific findings, statistics.)

- Where does the author do a good job of conveying factual material as well as personal perspective? Where does the author fail to do so? If solutions to a problem are offered, are they believable, misguided, or promising?

- Which parts of the work (particular arguments, descriptions, chapters, etc.) are most effective and which parts are least effective? Why?

- Where (if at all) does the author convey personal prejudice, support illogical relationships, or present evidence out of its appropriate context?

Keep your opinions distinct and cite your sources

Remember, as you discuss the author’s major points, be sure to distinguish consistently between the author’s opinions and your own.

Keep the summary portions of your discussion concise, remembering that your task as a reviewer is to re-see the author’s work, not to re-tell it.

And, importantly, if you refer to ideas from other books and articles or from lecture and course materials, always document your sources, or else you might wander into the realm of plagiarism.

Include only that material which has relevance for your review and use direct quotations sparingly. The Writing Center has other handouts to help you paraphrase text and introduce quotations.

Write the conclusion

You will want to use the conclusion to state your overall critical evaluation.

You have already discussed the major points the author makes, examined how the author supports arguments, and evaluated the quality or effectiveness of specific aspects of the book or article.

Now you must make an evaluation of the work as a whole, determining such things as whether or not the author achieves the stated or implied purpose and if the work makes a significant contribution to an existing body of knowledge.

Consider the following questions:

- Is the work appropriately subjective or objective according to the author’s purpose?

- How well does the work maintain its stated or implied focus? Does the author present extraneous material? Does the author exclude or ignore relevant information?

- How well has the author achieved the overall purpose of the book or article? What contribution does the work make to an existing body of knowledge or to a specific group of readers? Can you justify the use of this work in a particular course?

- What is the most important final comment you wish to make about the book or article? Do you have any suggestions for the direction of future research in the area? What has reading this work done for you or demonstrated to you?

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Trends and Motivations in Critical Quantitative Educational Research: A Multimethod Examination Across Higher Education Scholarship and Author Perspectives

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Christa E. Winkler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1700-5444 1 &

- Annie M. Wofford ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2246-1946 2

To challenge “objective” conventions in quantitative methodology, higher education scholars have increasingly employed critical lenses (e.g., quantitative criticalism, QuantCrit). Yet, specific approaches remain opaque. We use a multimethod design to examine researchers’ use of critical approaches and explore how authors discussed embedding strategies to disrupt dominant quantitative thinking. We draw data from a systematic scoping review of critical quantitative higher education research between 2007 and 2021 ( N = 34) and semi-structured interviews with 18 manuscript authors. Findings illuminate (in)consistencies across scholars’ incorporation of critical approaches, including within study motivations, theoretical framing, and methodological choices. Additionally, interview data reveal complex layers to authors’ decision-making processes, indicating that decisions about embracing critical quantitative approaches must be asset-based and intentional. Lastly, we discuss findings in the context of their guiding frameworks (e.g., quantitative criticalism, QuantCrit) and offer implications for employing and conducting research about critical quantitative research.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Across the field of higher education and within many roles—including policymakers, researchers, and administrators—key leaders and educational partners have historically relied on quantitative methods to inform system-level and student-level changes to policy and practice. This reliance is rooted, in part, on the misconception that quantitative methods depict the objective state of affairs in higher education. This perception is not only inaccurate but also dangerous, as the numbers produced from quantitative methods are “neither objective nor color-blind” (Gillborn et al., 2018 , p. 159). In fact, like all research, quantitative data collection and analysis are informed by theories and beliefs that are susceptible to bias. Further, such bias may come in multiple forms such as researcher bias and bias within the statistical methods themselves (e.g., Bierema et al., 2021 ; Torgerson & Torgerson, 2003 ). Thus, if left unexamined from a critical perspective, quantitative research may inform policies and practices that fuel the engine of cultural and social reproduction in higher education (e.g., Bourdieu, 1977 ).

Largely, critical approaches to higher education research have been dominated by qualitative methods (McCoy & Rodricks, 2015 ). While qualitative approaches are vital, some have argued that a wider conceptualization of critical inquiry may propel our understanding of processes in higher education (Stage & Wells, 2014 ) and that critical research need not be explicitly qualitative (refer to Sablan, 2019 ; Stage, 2007 ). If scholars hope to embrace multiple ways of challenging persistent inequities and structures of oppression in higher education, such as racism, advancing critical quantitative work can help higher education researchers “expose and challenge hidden assumptions that frequently encode racist perspectives beneath the façade of supposed quantitative objectivity” (Gillborn et al., 2018 , p. 158).

Across professional networks in higher education, the perspectives of association leaders (e.g., Association for the Study of Higher Education [ASHE]) have often placed qualitative and quantitative research in opposition to each other, with qualitative research being a primary way to amplify the voices of systemically minoritized students, faculty, and staff (Kimball & Friedensen, 2019 ). Yet, given the vast growth of critical higher education research (e.g., Byrd, 2019 ; Espino, 2012 ; Martínez-Alemán et al., 2015 ), recent ASHE presidents have recognized how prior leaders planted transformative seeds of critical theory and praxis (Renn, 2020 ) and advocated for critical higher education scholarship as a disrupter (Stewart, 2022 ). With this shift in discourse, many members of the higher education research community have also grown their desire to expand upon the legacy of critical research—in both qualitative and quantitative forms.

Critical quantitative approaches hold promise as one avenue for meeting recent calls to embrace equity-mindedness and transform the future of higher education research, yet current structures of training and resources for quantitative methods lack guidance on engaging such approaches. For higher education scholars to advance critical inquiry via quantitative methods, we must first understand the extent to which such approaches have been adopted. Accordingly, this study sheds light on critical quantitative approaches used in higher education literature and provides storied insights from the experiences of scholars who have engaged critical perspectives with quantitative methods. We were guided by the following research questions:

To what extent do higher education scholars incorporate critical perspectives into quantitative research?

How do higher education scholars discuss specific strategies to leverage critical perspectives in quantitative research?

Contextualizing Existing Critical Approaches to Quantitative Research

To foreground our analysis of literature employing critical quantitative lenses to studies about higher education, we first must understand the roots of such framing. Broadly, the foundations of critical quantitative approaches align with many elements of equity-mindedness. Equity-mindedness prompts individuals to question divergent patterns in educational outcomes, recognize that racism is embedded in everyday practices, and invest in un/learning the effects of racial identity and racialized expectations (Bensimon, 2018 ). Yet, researchers’ commitments to critical quantitative approaches stand out as a unique thread in the larger fabric of opportunities to embrace equity-mindedness in higher education research. Below, we discuss three significant publications that have been widely applied as frameworks to engage critical quantitative approaches in higher education. While these publications are not the only ones associated with critical inquiry in quantitative research, their evolution, commonalities, and distinctions offer a robust background of epistemological development in this area of scholarship.

Quantitative Criticalism (Stage, 2007 )

Although some higher education scholars have applied critical perspectives in their research for many years, Stage’s ( 2007 ) introduction of quantitative criticalism was a salient contribution to creating greater discourse related to such perspectives. Quantitative criticalism, as a coined paradigmatic approach for engaging critical questions using quantitative data, was among the first of several crucial publications on this topic in a 2007 edition of New Directions for Institutional Research . Collectively, this special issue advanced perspectives on how higher education scholars may challenge traditional positivist and post-positivist paradigms in quantitative inquiry. Instead, researchers could apply (what Stage referred to as) quantitative criticalism to develop research questions centering on social inequities in educational processes and outcomes as well as challenge widely accepted models, measures, and analytic practices.

Notably, Stage ( 2007 ) grounded the motivation for this new paradigmatic approach in the core concepts of critical inquiry (e.g., Kincheloe & McLaren, 1994 ). Tracing critical inquiry back to the German Frankfurt school, Stage discussed how the principles of critical theory have evolved over time and highlighted Kincheloe and McLaren’s ( 1994 ) definition of critical theory as most relevant to the principles of quantitative criticalism. Kincheloe and McLaren’s definition of critical describes how researchers applying critical paradigms in their scholarship center concepts such as socially and historically created power structures, subjectivity, privilege and oppression, and the reproduction of oppression in traditional research approaches. Perhaps most importantly, Kincheloe and McLaren urge scholars to be self-conscious in their decision making—a tall ask of quantitative scholars operating from positivist and post-positivist vantage points.

In advancing quantitative criticalism, Stage ( 2007 ) first argued that all critical scholars must center their outcomes on equity. To enact this core focus on equity in quantitative criticalism, Stage outlined two tasks for researchers. First, critical quantitative researchers must “use data to represent educational processes and outcomes on a large scale to reveal inequities and to identify social or institutional perpetuation of systematic inequities in such processes and outcomes” (p. 10). Second, Stage advocated for critical quantitative researchers to “question the models, measures, and analytic practices of quantitative research in order to offer competing models, measures, and analytic practices that better describe experiences of those who have not been adequately represented” (p. 10). Stage’s arguments and invitations for criticalism spurred crucial conversations, many of which led to the development of a two-part series on critical quantitative approaches in New Directions for Institutional Research (Stage & Wells, 2014 ; Wells & Stage, 2015 ). With nearly a decade of new perspectives to offer, manuscripts within these subsequent special issues expanded the concepts of quantitative criticalism. Specifically, these new contributions advanced the notion that quantitative criticalism should include all parts of the research process—instead of maintaining a focus on paradigm and research questions alone—and made inroads when it came to challenging the (default, dominant) process of quantitative research. While many scholars offered noteworthy perspectives in these special issues (Stage & Wells, 2014 ; Wells & Stage, 2015 ), we now turn to one specific article within these special issues that offered a conceptual model for critical quantitative inquiry.

Critical Quantitative Inquiry (Rios-Aguilar, 2014 )

Building from and guided by the work of other criticalists (namely, Estela Bensimon, Sara Goldrick-Rab, Frances Stage, and Erin Leahey), Rios-Aguilar ( 2014 ) developed a complementary framework representing the process and application of critical quantitative inquiry in higher education scholarship. At the heart of Rios-Aguilar’s conceptualization lies the acknowledgment that quantitative research is a human activity that requires careful decisions. With this foundation comes the pressing need for quantitative scholars to engage in self-reflection and transparency about the processes and outcomes of their methodological choices—actions that could potentially disrupt traditional notions and deficit assumptions that maintain systems of oppression in higher education.

Rios-Aguilar ( 2014 ) offered greater specificity to build upon many principles from other criticalists. For one, methodologically, Rios-Aguilar challenged the notion of using “fancy” statistical methods just for the sake of applying advanced methods. Instead, she argued that critical quantitative scholars should engage “in a self-reflection of the actual research practices and statistical approaches (i.e., choice of centering approach, type of model estimated, number of control variables, etc.) they use and the various influences that affect those practices” (Rios-Aguilar, 2014 , p. 98). In this purview, scholars should ensure that all methodological choices advance their ability to reveal inequities; such choices may include those that challenge the use of reference groups in coding, the interpretation of statistics in ways that move beyond p -values for statistical significance, or the application and alignment of theoretical and conceptual frameworks that focus on the assets of systemically minoritized students. Rios-Aguilar also noted, in agreement with the foundations of equity-mindedness and critical theory, that quantitative criticalists have an obligation to translate findings into tangible changes in policy and practice that can redress inequities.

Ultimately, Rios-Aguilar’s ( 2014 ) framework focused on “the interplay between research questions, theory, method/research practices, and policy/advocacy” to identify how quantitative criticalists’ scholarship can be “relevant and meaningful” (p. 96). Specifically, Rios-Aguilar called upon quantitative criticalists to ask research questions that center on equity and power, engage in self-reflection about their data sources, analyses, and disaggregation techniques, attend to interpretation with practical/policy-related significance, and expand beyond field-level silos in theory and implications. Without challenging dominant approaches in quantitative higher education research, Rios-Aguilar noted that the field will continue to inaccurately capture the experiences of systemically minoritized students. In college access and success, for example, ignoring this need for evolving approaches and models would continue what Bensimon ( 2007 ) referred to as the Tintonian Dynasty, with scholars widely applying and citing Tinto’s work but failing to acknowledge the unique experiences of systemically minoritized students. These and other concrete recommendations have served as a springboard for quantitative criticalists, prompting scholars to incorporate critical approaches in more cohesive and congruent ways.

QuantCrit (Gillborn et al., 2018 )

As an epistemologically different but related form of critical quantitative scholarship, QuantCrit—quantitative critical race theory—has emerged as a vital stream of inquiry that applies critical race theory to methodological approaches. Given that statistical methods were developed in support of the eugenics movement (Zuberi, 2001 ), QuantCrit researchers must consider how the “norms” of quantitative research support white supremacy (Zuberi & Bonilla-Silva, 2008 ). Fortunately, as Garcia et al. ( 2018 ) noted, “[t]he problems concerning the ahistorical and decontextualized ‘default’ mode and misuse of quantitative research methods are not insurmountable” (p. 154). As such, the goal of QuantCrit is to conduct quantitative research in a way that can contextualize and challenge historical, social, political, and economic power structures that uphold racism (e.g., Garcia et al., 2018 ; Gillborn et al., 2018 ).

In coining the term QuantCrit, Gillborn et al. ( 2018 ) provided five QuantCrit tenets adapted from critical race theory. First, the centrality of racism offers a methodological and political statement about how racism is complex, fluid, and rooted in social dynamics of power. Second, numbers are not neutral demonstrates an imperative for QuantCrit researchers—one that prompts scholars to understand how quantitative data have been collected and analyzed to prioritize interests rooted in white, elite worldviews. As such, QuantCrit researchers must reject numbers as “true” and as presenting a unidimensional truth. Third, categories are neither “natural” nor given prompts researchers to consider how “even the most basic decisions in research design can have fundamental consequences for the re/presentation of race inequity” (Gillborn et al., 2018 , p. 171). Notably, even when race is a focus, scholars must operationalize and interpret findings related to race in the context of racism. Fourth, prioritizing voice and insight advances the notion that data cannot “speak for itself” and numerous interpretations are possible. In QuantCrit, this tenet leverages experiential knowledge among People of Color as an interpretive tool. Finally, the fifth tenet explicates how numbers can be used for social justice but statistical research cannot be placed in a position of greater legitimacy in equity efforts relative to qualitative research. Collectively, although Gillborn et al. ( 2018 ) stated that they expect—much like all epistemological foundations—the tenets of QuantCrit to be expanded, we must first understand how these stated principles arise in critical quantitative research.

Bridging Critical Quantitative Concepts as a Guiding Framework

Guided by these framings (i.e., quantitative criticalism, critical quantitative inquiry, QuantCrit) as a specific stream of inquiry within the larger realm of equity-minded educational research, we explore the extent to which the primary elements of these critical quantitative frameworks are applied in higher education. Across the framings discussed, the commitment to equity-mindedness contributes to a shared underlying essence of critical quantitative approaches. Not only do Stage, Rios-Aguilar, and Gillborn et al. aim for researchers to center on inequities and commit to disrupting “neutral” decisions about and interpretations of statistics, but they also advocate for critical quantitative research (by any name) to serve as a tool for advocacy and praxis—creating structural changes to discriminatory policies and practices, rather than ceasing equity-based commitments with publications alone. Thus, the conceptual framework for the present study brings together alignments and distinctions in scholars’ motivations and actualizations of quantitative research through a critical lens.

Specifically, looking to Stage ( 2007 ), quantitative criticalists must center on inequity in their questions and actions to disrupt traditional models, methods, and practices. Second, extending critical inquiry through all aspects of quantitative research (Rios-Aguilar, 2014 ), researchers must interrogate how critical perspectives can be embedded in every part of research. The embedded nature of critical approaches should consider how study questions, frameworks, analytic practices, and advocacy are developed with intentionality, reflexivity, and the goal of unmasking inequities. Third, centering on the five known tenets of QuantCrit (Gillborn et al., 2018 ), QuantCrit researchers should adapt critical race theory for quantitative research. Although QuantCrit tenets are likely to be expanded in the future, the foundations of such research should continue to acknowledge the centrality of racism, advance critiques of statistical neutrality and categories that serve white racial interests, prioritize the lived experiences of People of Color, and complicate how statistics can be one—but not the lone—part of social justice endeavors.

Over many years, higher education scholars have advanced more critical research, as illustrated through publication trends of critical quantitative manuscripts in higher education (Wofford & Winkler, 2022 ). However, the application of critical quantitative approaches remains laced with tensions among paradigms and analytic strategies. Despite recent systematic examinations of critical quantitative scholarship across educational research broadly (Tabron & Thomas, 2023 ), there has yet to be a comprehensive, systematic review of higher education studies that attempt to apply principles rooted in quantitative criticalism, critical quantitative inquiry, and QuantCrit. Thus, much remains to be learned regarding whether and how higher education researchers have been able to apply the principles previously articulated. In order for researchers to fully (re)imagine possibilities for future critical approaches to quantitative higher education research, we must first understand the landscape of current approaches.

Study Aims and Role of the Researchers

Study aims and scope.

For this study, we examined the extent to which authors adopted critical quantitative approaches in higher education research and the trends in tools and strategies they employed to do so. In other words, we sought to understand to what extent, and in what ways, authors—in their own perspectives—applied critical perspectives to quantitative research. We relied on the nomenclature used by the authors of each manuscript (e.g., whether they operated from the lens of quantitative criticalism, QuantCrit, or another approach determined by the authors). Importantly, our intent was not to evaluate the quality of authors’ applications of critical approaches to quantitative research in higher education.

Researcher Positionality

As with all research, our positions and motivations shape how we conceptualized and executed the present study. We come to this work as early career higher education faculty, drawn to the study of higher education as one way to rectify educational disparities, and thus are both deeply invested in understanding how critical quantitative approaches may advance such efforts. After engaging in initial discussions during an association-sponsored workshop on critical quantitative research in higher education, we were motivated to explore these perspectives, understand trends in our field, and inform our own empirical engagement. Throughout our collaboration, we were also reflexive about the social privileges we hold in the academy and society as white, cisgender women—particularly given how quantitative criticalism and QuantCrit create inroads for systemically minoritized scholars to combat the erasure of perspectives from their communities due to small sample sizes. As we work to understand prior critical quantitative endeavors, with the goal of creating opportunity for this work to flourish in the future, we continually reflect on how we can use our positions of privilege to be co-conspirators in the advancement of quantitative research for social justice in higher education.

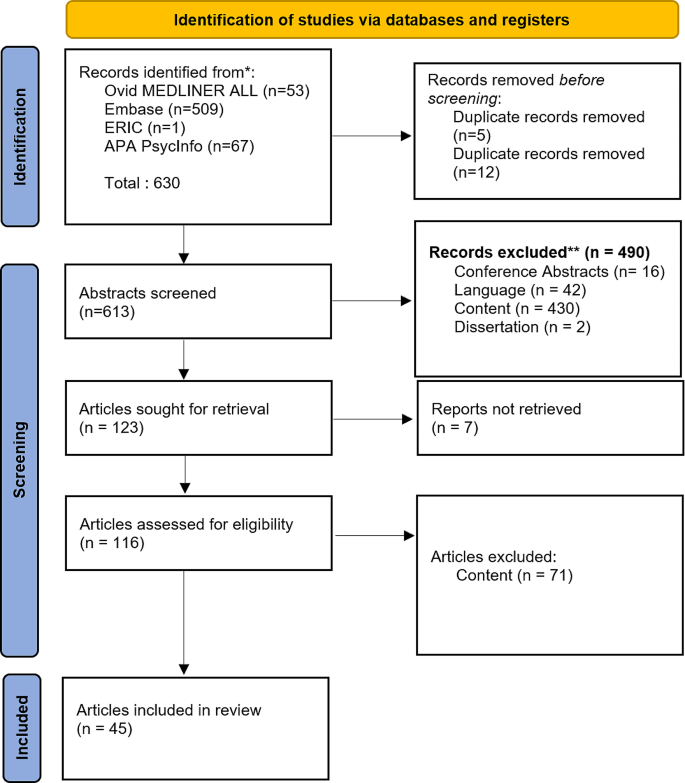

This study employed a qualitatively driven multimethod sequential design (Hesse-Biber et al., 2015 ) to illuminate how critical quantitative perspectives and methods have been applied in higher education contexts over 15 years. Anguera et al. ( 2018 ) noted that the hallmark feature of multimethod studies is the coexistence of different methodologies. Unlike mixed-methods studies, which integrate both quantitative and qualitative methods, multimethod studies can be exclusively qualitative, exclusively quantitative, or a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. A multimethod research design was also appropriate given the distinct research questions in this study—each answered using a different stream of data. Specifically, we conducted a systematic scoping review of existing literature and facilitated follow-up interviews with a subset of corresponding authors from included publications, as detailed below and in Fig. 1 . We employed a systematic scoping review to examine the extent to which higher education scholars incorporated critical perspectives into quantitative research (research question one), and we then conducted follow-up interviews to elucidate how those scholars discussed specific strategies for leveraging critical perspectives in their quantitative research (research question two).

Sequential multimethod approach to data collection and analysis

Given the scope of our work—which examined the extent to which, and in what ways, authors applied critical perspectives to quantitative higher education research—we employed an exploratory approach with a constructivist lens. Using a constructivist paradigm allowed us to explore the many realities of doing critical quantitative research, with the authors themselves constructing truths from their worldviews (Magoon, 1977 ). In what follows, we contextualize both our methodological choices and the limitations of those choices in executing this study.

Data Sources

Systematic scoping review.

First, we employed a systematic scoping review of published higher education literature. Consistent with the purpose of a scoping review, we sought to “examine the extent, range, and nature” of critical quantitative approaches in higher education that integrate quantitative methods and critical inquiry (Arskey & O’Malley, 2005 , p. 6). We used a multi-stage scoping framework (Arskey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ) to identify studies that were (a) empirical, (b) conducted within a higher education context, and (c) guided by critical quantitative perspectives. We restricted our review to literature published in 2007 or later (i.e., since Stage’s formal introduction of quantitative criticalism in higher education). All studies considered for review were written in the English language.

The literature search spanned multiple databases, including Academic Search Premier, Scopus, ERIC, PsychINFO, Web of Science, SocINDEX , Psychological and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Sociological Abstracts, and JSTOR. To locate relevant works, we used independent and combined keywords that reflected the inclusion criteria, with the initial search resulting in 285 unique records for eligibility screening. All screening was conducted separately by both authors using the CADIMA online platform (Kohl et al., 2018). In total, 285 title/abstract records were screened for eligibility, with 40 full-text records subsequently screened for eligibility. After separately screening all records, we discussed inconsistencies in title/abstract and full-text eligibility ratings to reach consensus. This strategy led us to a sample of 34 manuscripts that met all inclusion criteria (Fig. 2 ).

Identification of systematic scoping review sample via literature search and screening

Systematic scoping reviews are particularly well-suited for initial examinations of emerging approaches in the literature (Munn et al., 2018 ), aligning with our goal to establish an initial understanding of the landscape of critical quantitative research applications in higher education. It also relies heavily on researcher-led qualitative review of the literature, which we viewed as a vital component of our study, as we sought to identify not just what researchers did (e.g., what topics they explored or in what outlets they did so), but also how they articulated their decision-making process in the literature. Alternative methods to examining the literature, such as bibliometric analysis, supervised topic modeling, and network analysis, may reveal additional insights regarding the scope and structure of critical quantitative research in higher education not addressed in the current study. As noted by Munn et al. ( 2018 ), systematic scoping reviews can serve as a useful precursor to more advanced approaches of research synthesis.

Semi-structured Interviews

To understand how scholars navigated the opportunities and tensions of critical quantitative inquiry in their research, we then conducted semi-structured interviews with authors whose work was identified in the scoping review. For each article meeting the review criteria ( N = 34), we compiled information about the corresponding author and their contact information as our sample universe (Robinson, 2014 ). Each corresponding author was contacted via email for participation in a semi-structured interview. There were 32 distinct corresponding authors for the 34 manuscripts, as two corresponding authors led two manuscripts each within our corpus of data. In the recruitment email, we provided corresponding authors with a link to a Qualtrics intake survey; this survey confirmed potential participants’ role as corresponding author on the identified manuscript, collected information about their professional roles and social identities, and provided information about informed consent in the study. Twenty-five authors responded to the Qualtrics survey, with 18 corresponding authors ultimately participating in an interview.

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted via Zoom and lasted approximately 45–60 min. The interview protocol began with questions about corresponding authors’ backgrounds, then moving into questions regarding their motivations for engaging in critical approaches to quantitative methods, navigation of the epistemological and methodological tensions that may arise when doing quantitative research with a critical lens, approaches to research design, frameworks, and methods that challenged quantitative norms, and experiences with the publication process for their manuscript included in the scoping review. In other words, we asked that corresponding authors explicitly relay the thought processes underlying their methodological choices in the article(s) from our scoping review. Importantly, given the semi-structured nature of these interviews, conversations also reflected participants’ broader trajectory to and through critical quantitative thinking as well as their general reflections about how the field of higher education has grappled with critical approaches to quantitative scholarship. To increase consistency in our data collection and the nature of these conversations, the first author conducted all interviews. With participants’ consent, we recorded each interview, had interviews professionally transcribed, and then de-identified data for subsequent analysis. All interview participants were compensated for their time and contributions with a $50 Amazon gift card.

At the conclusion of each interview, participants were given the opportunity to select their own pseudonym. A profile of interview participants, along with their self-selected pseudonyms, is provided in Table 1 . Although we invited all corresponding authors to participate in interviews, our sample may reflect some self-selection bias, as authors had to opt in to be represented in the interview data. Further, interview insights do not represent all perspectives from participants’ co-authors, some of which may diverge based on lived experiences, history with quantitative research, or engagement with critical quantitative approaches.

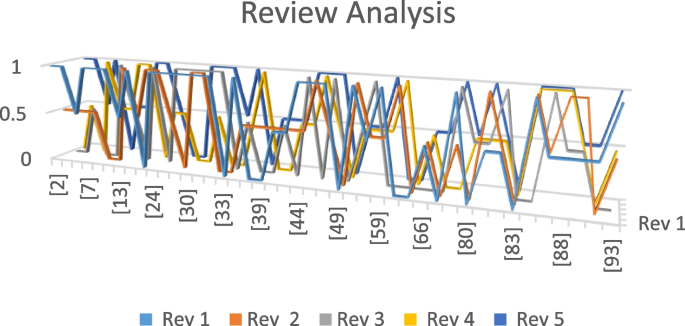

Data Analysis

After identifying the sample of 34 publications, we began data analysis for the scoping review by uploading manuscripts to Dedoose. Both researchers then independently applied a priori codes (Saldaña, 2015 ) from Stage’s ( 2007 ) conceptualization of quantitative criticalism, Rios-Aguilar’s ( 2014 ) framework for quantitative critical inquiry, and Gillborn et al.’s ( 2018 ) QuantCrit tenets (Table 2 ). While we applied codes in accordance with Stage’s and Rios-Aguilar’s conceptualizations to each article, codes relevant to Gillborn et al.’s tenets of QuantCrit were only applied to manuscripts where authors self-identified as explicitly employing QuantCrit. Given the distinct epistemological origin of QuantCrit from broader forms of critical quantitative scholarship, codes representing the tenets of QuantCrit reflect its origins in critical race theory and may not be appropriate to apply to broader streams of critical quantitative scholarship that do not center on racism (e.g., scholarship related to (dis)ability, gender identity, sexual identity and orientation). After individually completing a priori coding, we met to reconcile discrepancies and engage in peer debriefing (Creswell & Miller, 2000 ). Data synthesis involved tabulating and reporting findings to explore how each manuscript component aligned with critical quantitative frameworks in higher education research to date.

We analyzed interview data through a multiphase process that engaged deductive and inductive coding strategies. After interviews were transcribed and redacted, we uploaded the transcripts to Dedoose for collaborative qualitative coding. The second author read each transcript in full to holistically understand participants’ insights about generating critical quantitative research. During this initial read, the second author noted quotes that were salient to our question regarding the strategies that scholars use to employ critical quantitative approaches.

Then, using the a priori codes drawn from Stage’s ( 2007 ), Rios-Aguilar’s ( 2014 ) and Gillborn et al.’s ( 2018 ) conceptualizations relevant to quantitative criticalism, critical quantitative inquiry, and QuantCrit, we collaboratively established a working codebook for deductive coding by defining the a priori codes in ways that could capture how participants discussed their work. Although these a priori codes had been previously applied to the manuscripts in the scoping review, definitions and applications of the same codes for interview analysis were noticeably broader (to align with the nature of conversations during interviews). For example, we originally applied the code “policy/advocacy”—established from Rios-Aguilar's work—to components from the implications section of scoping review manuscripts. When (re)developed for deductive coding of interview data, however, we expanded the definition of “policy/advocacy” to include participants’ policy- and advocacy-related actions (beyond writing) that advanced critical inquiry and equity for their educational communities.

In the final phase of analysis, each research team member engaged in inductive coding of the interview data. Specifically, we relied on open coding (Saldaña, 2015 ) to analyze excerpts pertaining to participants’ strategies for employing critical quantitative approaches that were not previously captured by deductive codes. Through open coding, we used successive analysis to work in sequence from a single case to multiple cases (Miles et al., 2014 ). Then, as suggested by Saldaña ( 2015 ), we collapsed our initial codes into broader categories that allowed us insight regarding how participants’ strategies in critical quantitative research expanded beyond those which have been previously articulated. Finally, to draw cohesive interpretations from these data, we independently drafted analytic memos for each interview participant’s transcript, later bridging examples from the scoping review that mapped onto qualitative codes as a form of establishing greater confidence and trustworthiness in our multimethod design.

In introducing study findings through a synthesized lens that heeds our multimethod design, we organize the sections below to draw from both scoping review and interview data. Specifically, we organize findings into two primary areas that address authors’ (1) articulated motivations to adopt critical approaches to quantitative higher education research, and (2) methodological choices that they perceive to align with critical approaches to quantitative higher education research. Within these sections, we discuss several coherent areas where authors collectively grappled with tensions in motivation (i.e., broad motivations, using coined names of critical approaches, conveying positionality, leveraging asset-based frameworks) and method (i.e., using data sources and choosing variables, challenging coding norms, interpreting statistical results), all of which signal authors’ efforts to embody criticality in quantitative research about higher education. Given our sequential research questions, which first examined the landscape of critical quantitative higher education research and then asked authors to elucidate their thought processes and strategies underlying their approaches to these manuscripts, our findings primarily focus on areas of convergence across data sources; we do, however, highlight challenges and tensions authors faced in conducting such work.

Articulated Motivations in Critical Approaches to Quantitative Research

To date, critical quantitative researchers in higher education have heeded Stage’s ( 2007 ) call to use data to reveal the large-scale perpetuation of inequities in educational processes and outcomes. This emerged as a defining aspect of higher education scholars’ critical quantitative work, as all manuscripts ( N = 34) in the scoping review articulated underlying motivations to identify and/or address inequities.

Often, these motivations were reflected in the articulated research questions ( n = 31; 91.2%). For example, one manuscript sought to “critically examine […] whether students were differentially impacted” by an educational policy based on intersecting race/ethnicity, gender, and income (Article 29, p. 39). Others sought to challenge notions of homogeneity across groups of systemically minoritized individuals by “explor[ing] within-group heterogeneity” of constructs such as sense of belonging among Asian American students (Article 32, p. iii) and “challenging the assumption that [economically and educationally challenged] students are a monolithic group with the same values and concerns” (Article 31, p. 5). These underlying motivations for conducting critical quantitative research emerged most clearly in the named approaches, positionality statements, and asset-based frameworks articulated in manuscripts.

Adopting the Coined Names of Quantitative Criticalism, QuantCrit, and Related Approaches

Based on the inclusion criteria applied in the scoping review, we anticipated that all manuscripts would employ approaches that were explicitly critical and quantitative in nature. Accordingly, all manuscripts ( N = 34; 100%) adopted approaches that were coined as quantitative criticalism , QuantCrit , critical policy analysis (CPA), critical quantitative intersectionality (CQI) , or some combination of those terms. Twenty-one manuscripts (61.8%) identified their approach as quantitative criticalism, nine manuscripts (26.5%) identified their approach as QuantCrit, two manuscripts (5.9%) identified their approach as CPA, and two manuscripts (5.9%) identified their approach as CQI.

One of the manuscripts that applied quantitative criticalism broadly described it as an approach that “seeks to quantitatively understand the predictors contributing to completion for a specific population of minority students” (Article 34, p. 62), noting that researchers have historically “attempted to explain the experiences of [minority] students using theories, concepts, and approaches that were initially designed for white, middle and upper class students” (Article 34, p. 62). Although this example speaks only to the limited context and outcomes of one study, it highlights a broader theme found across articles; that is, quantitative criticalism was often leveraged to challenge dominant theories, concepts, and approaches that failed to represent systemically minoritized individuals’ experiences. In challenging dominant theories, QuantCrit applications were most explicitly associated with critical race theory and issues of racism. One manuscript noted that “QuantCrit recognizes the limitations of quantitative data as it cannot fully capture individual experiences and the impact of racism” (Article 29, p. 9). However, these authors subsequently noted that “quantitative methodology can support CRT work by measuring and highlighting inequities” (Article 29, p. 9). Several scholars who employed QuantCrit explicitly identified tenets of QuantCrit that they aimed to address, with several authors making clear how they aligned decisions with two tenets establishing that categories are not given and numbers are not neutral.

Despite broadly applying several of the coined names for critical realms of quantitative research, interview data revealed that several authors felt a palpable tension in labeling. Some participants, like Nathan, questioned the surface-level engagement that may come with coined names: “I don’t know, I think it’s the thinking and the thought processes and the intentionality that matters. How invested should we be in the label?” Nathan elaborated by noting how he has shied away from labeling some of his work as quantitative criticalist , given that he did not have a clear answer about “what would set it apart from the equity-minded, inequality-focused, structurally and systematically-oriented kind of work.” Similarly, Leo stated how labels could (un)intentionally stop short of the true mission for the research, recalling that he felt “more inclined to say that I’m employing critical quantitative leanings or influences from critical quant” because a true application of critical epistemology should be apparent in each part of the research process. Although most interview participants remained comfortable with labeling, we also note that—within both interview data and the articles themselves—authors sometimes presented varied source attributions for labels and conflated some of the coined names, representing the messiness of this emerging body of research.

Challenging Objectivity by Conveying Researcher Positionality

Positionality statements acknowledge the influence of scholars’ identities and social positions on research decisions. Quantitative research has historically been viewed as an objective, value-neutral endeavor, with some researchers deeming positionality statements as unnecessary and inconsistent with the positivist paradigm from which such work is often conducted. Several interviewed authors noted that positivist or post-positivist roots of quantitative research characterized their doctoral training, which often meant that their “original thinking around statistics and research was very post-positivist” (Carter) or that “there really wasn’t much of a discussion, as far as I can remember as a doc student, about epistemology or ontology” (Randall). Although positionality statements have been generally rare in quantitative research studies, half of the manuscripts in our sample ( n = 17; 50.0%) included statements of researcher positionality. One interview participant, Gabrielle, discussed the importance of positionality statements as one way to challenge norms of quantitative research in saying:

It’s not objective, right? I think having more space to say, “This is why I chose the measures I chose. This is how I’m coming to this work. This is why it matters to me. This is my positioning, right?” I think that’s really important in quantitative work…that raises that level of consciousness to say these are not just passive, like every decision you make in your research is an active decision.

While Gabrielle, as well as Carter and Randall, all came to be advocates of positionality statements in quantitative scholarship through different pathways, it became clear through these and other interviews that positionality statements were one way to bring greater transparency to a traditionally value-neutral space.

As an additional source of contextual data, we reviewed submission guidelines for the peer-reviewed journals in which manuscripts were published. Not one of the 15 peer-reviewed outlets represented in our scoping review sample required that authors include positionality statements. One outlet, Journal of Diversity in Higher Education (where two scoping review articles were printed), offered “inclusive reporting standards” where they recommended that authors include reflexivity and positionality statements in their submitted manuscripts (American Psychological Association, 2024 ). Another outlet, Teachers College Record (where one scoping review article was printed), mentioned positionality statements in their author instructions. Yet, Teachers College Record did not require nor recommend the inclusion of author positionality statements; rather, they offered recommendations if authors chose to include them. Specifically, they suggested that if authors chose to include a positionality statement, it should be “more than demographic information or abstract statements” (Sage Journals, 2024 ). The remaining 13 peer-reviewed outlets from the scoping review data made no mention of author reflexivity or positionality in their author guidelines.

When present, the scoping review revealed that positionality statements varied in form and content. Some positionality statements were embedded in manuscript narratives, while others existed as separate tables with each author’s positionality represented as a separate row. In content, it was most common for authors to identify how their identities and experiences motivated their work. For example, one author noted their shared identity with their research participants as a low-income, first-generation Latina college student (Article 2, p. 25). Another author discussed the identity that they and their co-author shared as AAPI faculty, making the research “personally relevant for [them]” (Article 11, p. 344),

In interviews, participants recalled how the relationship between their identities, lived experiences, and motivations for critical approaches to quantitative research were all intertwined. Leo mentioned, “naming who we are in a study helps us be very forthright with the pieces that we’re more likely to attend to.” Yet, Leo went on to say that “one of the most cosmetic choices that people see in critically oriented quantitative research is our positionality statements,” which other participants noted about how information in positionality statements is presented. In several interviews, authors’ reflections on whether these statements should appear as lists of identities or deeper statements about reflexivity presented a clear tension. For some, positionality statements were places to “identify ourselves and our social locations” (David) or “brand yourself” as a critical quantitative scholar to meet “trendy” writing standards in this area (Michelle). Yet, others felt such statements fall short in revealing “how this study was shaped by their background identities and perspectives” (Junco) or appear to “be written in response to the context of the research or people participating” (Ginger). Ultimately, many participants felt that shaping honest positionality statements that better convey “the assumptions, and the biases and experiences we’ve all had” (Randall) was one area where quantitative higher education scholars could significantly improve their writing to reflect a critical lens.

Some manuscripts also clarified how authors’ identities and social positions reshaped the research process and product. For instance, authors of one manuscript reported being “guided by [their] cultural intuition” throughout the research (Article 17, p. 218). Alternatively, another author described the narrative style of their manuscript as intentionally “autobiographical and personally reflexive” in order “to represent the connections [they] made between [their] own experiences and findings that emerged” from their work (Article 28, p. 56). Taken together, among the manuscripts that explicitly included positionality statements, these remarks make clear that authors had widely varying approaches to their reflexivity and writing processes.

Actualizing Asset-Based Frameworks

Notably, conceptual and theoretical frameworks emerged as a common way for critical quantitative scholars to pursue equitable educational processes and outcomes in higher education research. Nearly all ( n = 32; 94.1%) manuscripts explicitly challenged dominant conceptual and theoretical models. Some authors enacted this challenge by countering canonical constructs and theories in the framing of their study. For example, several manuscripts addressed critiques of theoretical concepts such as integration and sense of belonging in building the conceptual framework for their own studies. Other manuscripts were constructed with the underlying goal to problematize and redefine frameworks, such as engagement for Latina/e/o/x students or the “leaky pipeline” discourse related to broadening participation in the sciences.

Across interviews, participants challenged deficit framings or “traditional” theoretical and conceptual approaches in many ways. Some frameworks are taken as a “truism in higher ed” (Leo), such as sense of belonging and Astin’s ( 1984 ) I-E-O model, and these frameworks were sometimes purposefully used to disrupt their normative assumptions. Randall, for one, recalled using a more normative higher education framework but opted to think about this framework “as more culturalized” than had previously been done. Further, Carter noted that “thinking about the findings in an anti-deficit lens” comprised a large portion of critical quantitative approaches. Using frameworks for asset-based interpretation was further exemplified by Caroline stating, “We found that Black students don’t do as well, but it’s not the fault of Black students.” Instead, Caroline challenged deficit understandings through the selected framework and implications for institutional policy. Collectively, challenging normative theoretical underpinnings in higher education was widely favored among participants, and Jackie hoped that “the field continues to turn a critical lens onto itself, to grow and incorporate new knowledges and even older forms of knowledge that maybe it hasn’t yet.”

Alternatively, some participants discussed rejecting widely used frameworks in higher education research in favor of adapting frameworks from other disciplines. For example, QuantCrit researchers drew from critical race theory (and related frameworks, such as intersectionality) to quantitatively examine higher education topics in ways that value the knowledge of People of Color. In using these frameworks, which have origins in critical legal and Black feminist theorization, interview participants noted how important it was “to put yourself out there with talking about race and racism” (Isabel) and connect the statistics “back to systems related to power, privilege, and oppression [because] it’s about connecting [results] to these systemic factors that shape experience, opportunities, barriers, all of that kind of stuff” (Jackie). Further, several authors related pulling theoretical lenses from sociology, gender studies, feminist studies, and queer studies to explore asset-based theorization in higher education contexts and potentially (re)build culturally relevant concepts for quantitative measurement in higher education.

Embodying Criticality in Methodological Sources, Approaches, and Interpretations

Moving beyond underlying motivations of critical quantitative higher education research, scoping review authors also frequently actualized the task of questioning and reconstructing “models, measures, and analytic practices [to] better describe experiences of those who have not been adequately represented” (Stage, 2007 , p. 10). Common across all manuscripts ( N = 34) was the discussion of specific ways in which authors’ critical quantitative approaches informed their analytic decisions. In fact, “analytic practices” was by far the most prevalent code applied to the manuscripts in our dataset, with 342 total references across the 34 manuscripts. This amounted to 20.8% of the excerpts in the scoping review dataset being coded as reflecting critical quantitative approaches to analytic practices, specifically.

Interestingly, many analytic approaches reflected what some would consider “standard” quantitative methodological tools. For example, manuscripts employed factor analysis to assess measures, t-tests to examine differences between groups, and hierarchical linear regression to examine relationships in specific contexts. Some more advanced, though less commonly applied, methods included measurement invariance testing and latent class analysis. Thus, applying a critical quantitative lens tended not to involve applying a separate set of analytic tools; rather, the critical lens was reflected in authors’ selection of data sources and variables, approaches to data coding and (dis)aggregation, and interpretation of statistical results.

Selecting Data Sources and Variables

Although scholars were explicit in their underlying motivations and approaches to critical quantitative research, this did not often translate into explicitly critical data collection endeavors. Most manuscripts ( n = 29; 85.3%) leveraged existing measures and data sources for quantitative analysis. Existing data sources included many national, large-scale datasets including the Educational Longitudinal Study (NCES), National Survey of Recent College Graduates (NSF), and the Current Population Survey (U.S. Census Bureau). Other large-scale data sources reflecting specific higher education contexts and populations included the HEDS Diversity and Equity Campus Climate Survey, Learning About STEM Student Outcomes (LASSO) platform, and National Longitudinal Survey of Freshmen. Only five manuscripts (14.7%) conducted analysis using original data collected and/or with newly designed measures.

It was apparent, however, that many authors grappled with challenges related to using existing data and measures. Interview participants’ stories crystallized the strengths and limitations of secondary data. Over half of the interview participants in our study spoke about their choices regarding quantitative data sources. Some participants noted that surveys “weren’t really designed to ask critical questions” (Sarah) and discussed the issues with survey data collected around sex and gender (Jessica). Still, Sarah and Jessica drew from existing survey data to complicate the higher education experiences they aimed to understand and tried to leverage critical framing to question “traditional” definitions of social constructs. In another discussion about data sources and the design of such sources, Carter expanded by saying:

I came in without [being] able to think through the sampling or data collection portion, but rather “this is what I have, how do I use it in a way that is applying critical frameworks but also staying true to the data themselves.” That is something that looks different for each study.

In discussing quantitative data source design, more broadly, Tyler added: “In a lot of ways, all quantitative methods are mixed methods. All of our measures should be developed with a qualitative component to them.” In the scoping review articles, one example of this qualitative component is evident within the cognitive interviews that Sablan ( 2019 ) employed to validate survey items. Finally, several participants noted how crucial it is to “just be honest and acknowledge the [limitations of secondary data] in the paper” (Caroline) and “not try to hide [the limitations]” (Alexis), illustrating the value of increased transparency when it comes to the selection and use of existing quantitative data in manuscripts advancing critical perspectives.

Regardless of data source, attention to power, oppression, and systemic inequities was apparent in the selection of variables across manuscripts. Many variables, and thus the associated models, captured institutional contexts and conditions. The multilevel nature of variables, which extended beyond individual experiences, aligned with authors’ articulated motivations to disrupt inequitable educational processes and outcomes, which are often systemic and institutionalized in nature. For one, David explained key motivations behind his analytic process: “We could have controlled for various effects, but we really wanted to see how are [the outcomes] differing by these different life experiences?” David’s focus on moving past “controlling” for different effects shows a deep level of intentionality that was reflected among many participants. Carter expanded on this notion by recalling how variable selection required, “thinking through how I can account for systemic oppression in my model even though it’s not included in the survey…I’ve never seen it measured.” Further, Leo discussed how reflexivity shaped variable selection and shared: “Ultimately, it’s thinking about how do these environments not function in value-neutral ways, right? It’s not just selecting X, Y, and Z variable to include. It’s being able to interrogate [how] these variables represent environments that are not power neutral.” The process of selecting quantitative data sources and variables was perhaps best summed up by Nick, who concisely shared, “it’s been very iterative.” Indeed, most participants recalled how their methodological processes necessitated reflexivity—an iterative process of continually revisiting assumptions one brings to the quantitative research process (Jamieson et al., 2023 )—and a willingness to lean into innovative ways of operationalizing data for critical purposes.

Challenging the Norms of Coding

An especially common way of enacting critical principles in quantitative research was to challenge traditional norms of coding. This emerged in three primary ways: (1) disaggregation of categories to reflect heterogeneity in individuals’ experiences, (2) alternative approaches to identifying reference groups, and (3) efforts to capture individuals’ intersecting identities. Across manuscripts, authors often intentionally disaggregated identity subgroups (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender) and ran distinct analytical models for each subgroup separately. In interviews, Junco expressed that running separate models was one way that analyses could cultivate a different way of thinking about racial equity. Specifically, Junco challenged colleagues’ analytic processes by asking whether their research questions “really need to focus on racial comparison?” Junco then pushed her colleagues by asking, “can we make a different story when we look at just the Black groups? Or when we look at only Asian groups, can we make a different story that people have not really heard?” Isabel added that focusing on measurement for People of Color allowed for them (Isabel and her research collaborators) to “apply our knowledge and understanding about minoritized students to understand what the nuances were.” In nearly one third of the manuscripts ( n = 11; 32.4%), focusing on single group analyses emerged as one way that QuantCrit scholars disrupted the perceived neutrality of numbers and how categories have previously been established to serve white, elite interests. Five of those manuscripts (14.7%) explicitly focused on understanding heterogeneity within systemically minoritized subpopulations, including Asian American, Latina/e/o/x, and Black students.

It was not the case, however, that authors avoided group comparisons altogether. For example, one team of authors used separate principal components analysis (PCA) models for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students with the explicit intent of comparing models between groups. The authors noted that “[t]ypically, monolithic comparisons between racial groups perpetuate deficit thinking and marginalization.” However, they sought to “highlight the nuance in belonging for Indigenous community college students as it differs from the White-centric or normative standards” by comparing groups from an asset-driven perspective (Article 5, p. 7). Thus, in cases where critical quantitative scholars included group comparisons, the intentionality underlying those choices as a mechanism to highlight inequities and/or contribute to asset-based narratives was apparent.

Four manuscripts (11.8%) were explicit in their efforts to identify alternative analytic methods to normative reference groups. Reference groups are often required when building quantitative models with categorical variables such as racial/ethnic and gender identity. Often, dominant identities (e.g., respondents who are white and/or men) comprise the largest portion of a research sample and are selected as the comparison group, typifying experiences of individuals with those dominant identities. To counter the traditional practice of reference groups, some manuscript authors stated using effect coding, often referencing the work of Mayhew and Simonoff ( 2015 ), and dynamic centering as two alternatives. Effect coding (used in three manuscripts) removes the need for a reference group; instead, all groups are compared to the overall sample mean. Dynamic centering (used in one manuscript), on the other hand, uses a reference group but one that is intentionally selected based on the construct in question, as opposed to relying on sample size or dominant identities.