Childhood Trauma - Free Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Childhood Trauma refers to distressing or harmful experiences that happen to children, which may have long-lasting effects on their emotional and physical well-being. Essays could delve into the types of childhood trauma, its short and long-term impacts, intervention strategies, and how support systems can mitigate its adverse effects. We’ve gathered an extensive assortment of free essay samples on the topic of Childhood Trauma you can find at Papersowl. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Effects of Childhood Trauma on Children Development

Anyone can experience trauma at any time. The trauma can be caused by nature, human beings or by oneself. People endure much when they experience trauma and their ability to handle it can determine the level of the effect of the trauma and their long-term well-being. Reportedly, children are incredibly susceptible to trauma because their brain and coping skills are still developing. Thus, they often grapple with long terms effects of uncontrolled trauma. While childhood trauma may vary regarding pervasiveness […]

Effects of Childhood Trauma on Development and Adulthood

It is no secret that experiencing childhood trauma can have many negative effects on an individual’s life both in childhood and adulthood. Trauma can include events such as physical or sexual abuse, surviving a serious car accident, witnessing a violent event, and more. As trauma is defined in the dictionary as a deeply distressing or disturbing experience, it is no surprise that a disturbing event during childhood can have negative effects throughout an individual’s lifetime. However, this paper will dive […]

Foster Care System Pros and Cons

"Foster care as a whole has become a broken and corrupt system that can no longer keep kids safe under its care. Everyday children are being placed in foster homes facing different forms of abuse, unloving parents, and even death. The system has only progressively gotten worse leaving behind children traumatized to a point where no amount of love or therapy can fix them. To inaugurate, the biggest issue with foster care is the inadequate placement of children in the […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Childhood Sexual Abuse – Preceding Hypersexualized Behavior

Hypersexual behavior is differentiated from paraphilia, or sexually deviant behavior, based on the criteria that hypersexual behaviors still fall within socially normal sexual activities (Kafka, 2010). Paraphilia refers to activities that do not fall within reasonably expected behavior, such as sexual interest in children or non-living entities (DSM-V, 2013). Both are defined as intense and frequent sexual behaviors that bring distress or other unintended negative consequences. This report looks at childhood sexual abuse, commonly referred to as CSA, in terms […]

Traumatic Childhood Memories

Most people are well aware of the concept of repression before ever stepping foot into a psychology class. The notion that a memory can be recalled after years of ignorance is a commonplace assumption, bringing with it the further assumption that it is a well-proven theory with the backing of researchers of psychology. Upon closer scrutiny, both the definition of and support for repression are seen as they truly are—complicated and controversial. The theory of repression originated with Jean-Martin Charcot […]

The Consequences of Homelessness – a Childhood on the Streets

“A therapeutic intervention with homeless children (2) often confronts us with wounds our words cannot dress nor reach. These young subjects seem prey to reenactments of a horror they cannot testify to” (Schweidson & Janeiro 113). According to Marcal, a stable environment and involved parenting are essential regarding ability to provide a healthy growing environment for a child (350). It is unfortunate then, that Bassuk et al. state that 2.5 million, or one in every 30 children in America are […]

Multiple Iimitations in Childhood

The researchers mentioned multiple limitations. While all the children in the study showed improved classroom compliance after implementation of the child play sessions, these changes were limited in a few of the children due to inconsistent compliance issues. Also, the changes made between the baseline and treatment phases was difficult to distinguish because this was a nonclinical sample and some of the children at baseline had only minor compliance issues. Future research should include post-intervention follow-up measures to provide an […]

Resilience through Childhood Trauma Shadows: Understanding and Healing

Within the intricate tapestry of human experience, the canvas of childhood unfurls as a pivotal chapter—a realm where innocence dances with curiosity, shaping the contours of the individuals we're destined to become. Yet, for some, this idyllic canvas is stained with the inky shadows of childhood trauma, casting a pall over the vibrant hues of youth and echoing through the corridors of time. Childhood trauma, a spectral presence, manifests in myriad forms. It is not merely the jagged edges of […]

Reimagining Childhood Trauma: a Psychologist’s Perspective

Childhood trauma, a labyrinthine phenomenon, often evokes conventional responses from psychologists. However, as practitioners, it is incumbent upon us to explore unconventional perspectives that may shed new light on this intricate subject. Traditionally, childhood trauma has been viewed through a lens of pathology, emphasizing its detrimental effects on mental health. While this perspective is undeniably valuable, it overlooks the resilience and adaptive capacities inherent in human nature. Instead of focusing solely on the scars left by trauma, let us consider […]

Childhood Trauma Unveiled: the Resilience and Redemption of Beth Thomas

Beth Thomas, a name that may not ring a bell for many, carries a story of resilience, transformation, and the power of compassion. Born in 1960, Beth's early life was marked by unimaginable challenges that would have left most broken. However, her journey from a traumatic childhood to a life of purpose is nothing short of remarkable. Growing up in Oklahoma, Beth Thomas experienced a childhood marred by abuse and neglect. Her parents, overwhelmed by their own struggles, failed to […]

Additional Example Essays

- Leadership and the Army Profession

- Why Abortion Should be Illegal

- Death Penalty Should be Abolished

- The Mental Health Stigma

- Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner

- Substance Abuse and Mental Illnesses

- A Reflection on Mental Health Awareness and Overcoming Stigma

- Does Arrest Reduce Domestic Violence

- Why Is Diversity Important in the Army? Uniting Strengths for Tomorrow's Battles

- Pursuit Of Happiness Summary

- Poverty in America

- Beauty Pageants for Children Should Be Banned: Protecting Child Well-being

How To Write an Essay About Childhood Trauma

Introduction to the complexity of childhood trauma.

Writing an essay about childhood trauma involves addressing a deeply sensitive and complex subject that has profound psychological and social implications. In your introduction, begin by defining childhood trauma, which can include experiences of abuse, neglect, witnessing violence, or enduring severe hardship. Emphasize the lasting impact these experiences can have on an individual’s development, mental health, and overall well-being. This introductory section should provide a foundation for exploring the various dimensions of childhood trauma, including its causes, symptoms, and long-term effects. It should sensitively set the stage for an in-depth analysis of this critical issue.

Examining the Causes and Manifestations of Childhood Trauma

In the body of your essay, delve into the various causes of childhood trauma. This can range from personal experiences such as physical or emotional abuse, to broader societal issues like war, poverty, or discrimination. Discuss the immediate and long-term psychological effects of trauma on children, which can manifest as anxiety, depression, behavioral issues, or difficulties in forming relationships. It’s important to base your analysis on research and studies in psychology and child development. The purpose of this section is to provide a comprehensive understanding of how childhood trauma occurs and its immediate impact on a child's life.

Long-Term Effects and Coping Mechanisms

Focus on the long-term effects of childhood trauma and the coping mechanisms individuals might develop. Explore how early traumatic experiences can shape personality, affect emotional regulation, and influence patterns of behavior into adulthood. Discuss the concept of resilience and the factors that contribute to positive outcomes in spite of traumatic experiences. This part of the essay should also consider the various therapeutic approaches used to support individuals with a history of childhood trauma, emphasizing the potential for healing and growth. Highlight the importance of early intervention and continued support for those affected by childhood trauma.

Concluding Thoughts on Addressing Childhood Trauma

Conclude your essay by summarizing the key points about the complexities and impacts of childhood trauma. Reflect on the importance of awareness, education, and societal support in addressing and preventing childhood trauma. Emphasize the role of communities, educators, healthcare professionals, and policymakers in creating environments that support the mental and emotional well-being of children. Your conclusion should not only provide closure to your essay but also encourage further thought and action on this crucial issue, underscoring the collective responsibility to protect and nurture the well-being of children.

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Testimonials

13 Reasons Why It’s OK to Write About Trauma in your College Applications — And How to Do So (a joint post by AdmissionsMom and McNeilAdmissions)

Hi everyone. This post is written by me, AdmissionsMom and McNeilAdmissions , TOGETHER. It’s a subject we both care about. We (your dynamic college-co nsultant duo) took up pens together to write what we believe is the first collaborative advice post in the sub’s history. Yay! Enjoy and thanks for reading.

Content warning: discussion of traumatic subjects: suicide, sexual abuse, trauma, self-harm

There is always a debate about what topics should be avoided at all cost on college essays. The short-list always boils down to a familiar crew of traumatic or “difficult” subjects. These include, but are not limited to, essays discussing severe depression, self-harm, eating disorders, experiences with sexual violence, family abuse, and experiences with the loss of a close relative or loved one.

First and foremost, you do NOT have to write about anything that makes you uncomfortable or that you don’t want to share. This isn’t the Overcoming Obstacles Olympics. Don’t feel pressure to tell any story that you don’t want to share. It is your story and if you don’t want to write about it, don’t. Period.

BUT, in our view, ruling out all essays that deal with trauma is wrong for two big reasons.

The first is that there is no actual, empirical evidence that essays that deal with trauma are less successful than those that don’t. The view that essays dealing with trauma correlate with lower admissions rates is based on counselor speculation and anecdotal evidence from students who applied, weren’t admitted, then tried to find a justification and decided it was their essays.

Both of us reflected on this. Here’s what we had to say.

- AdmissionsMom : I work with lots of students who have suffered from anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and addiction. They nearly always have to address their issues because of school disruption, and I have to say that their acceptances have remained right in range with the rest of my students.

- McNeilAdmissions : I counted, and I can provide more than 17 accounts about students of mine who have written about trauma and been admitted to T10 schools. I also asked a colleague of mine who is known as the “queen of Stanford admissions” and she said there was no trend among her students.

The other big reason is that traumas, while complex, can be sources of deep meaning, and therefore are potentially the exact sort of thing you want to consider . Traumatic experiences are often life-shaping, for better or for worse. So are the ways that we respond to and adapt in the face of trauma. The struggle to adapt and move forward after a traumatic experience may be one of the most important and meaningful things you’ve ever done. So a blanket prohibition on traumatic topics is equivalent, for many, to a blanket prohibition on writing an essay that feels personally meaningful and rewarding.

Categorically ruling out trauma stories also conflicts directly with the core lesson that most college consultants and counselors (including ours truly) are trying to advocate. That is, write a story that matters to you. This is a piece of corny but non-bullshit advice. As it turns out, it’s a rare moment (in a process that can be somewhat cynical) where meaning and strategy overlap. AOs want to read good essays. Good essays are good when they’re written about things that matter. You can attempt to hack together a good essay on a topic you don’t care about, but good luck.

So there are a few big intersecting threads about why you MIGHT want to write about your experience with trauma. First, there is no empirical evidence to recommend against it. Second, traumatic experiences are huge sources of personal meaning and significance, and it would be sad if you couldn’t use your writing as a tool for processing your experience. Third, meaningful essays = good essays = stronger applications.

So for anyone out there who wants to talk about their experience but who is struggling with how to do it, here are some things we want to say:

- You ARE allowed to talk about trauma in college apps.

- Your story is valid even if you haven’t turned your experience into a non-profit focused on preventing sexual assault, combating abuse, or eating disorders or done anything whatsoever to address the larger systemic issue. Your story and experience — your personal growth and lessons learned — are intrinsically valuable.

Now, here are some things to keep in mind if you decide to write an essay about a challenging or traumatic subject.

13 Reasons Why It’s OK to Write About Trauma in your College Applications — And How to Do So

- Colleges are not looking for perfect people . They are looking for real humans. Real Humans are flawed and have had flawed experiences. Some of our most compelling stories are the ones that open with showing our lives and experiences in less than favorable light. Throw in your lessons learned or what you have done to repair yourself and grow, and you have the makings of a compelling overcoming — or even redemption — story.

- Write with pride : This is your real life. Sometimes you need to be able to explain the circumstances in your life — and colleges want to know about any hardships you’ve had. They want to understand the context of your application, so don’t worry about thinking you’re asking the colleges to feel sorry for you (we hear kids say that all the time). We recognize you for your immense strength and courage, and we encourage you to speak your truth if you want to share your story. Colleges can’t know about your challenges and obstacles unless you tell them. Be proud of yourself for making it through your challenges and moving on to pursue college — that’s an accomplishment on its own!

- Consider the position of the admissions officer : “We’ve all had painful experiences. Many of these experiences are difficult to talk about, let alone write about. However, sometimes, if there is time, distance, and healing between you and the experience, you can not only revisit the experience but also articulate it as an example of how even the most painful of experiences can be reclaimed, transformed, and accepted for what they are, the building blocks of our unique identities.

If you can do this, go for it. When done well, these types of narratives are the most impactful. Do remember you are seeking admission into a community for which the admissions officer is the gatekeeper. They need to know that, if admitted, not only will you be okay but your fellow students will be okay as wel l.” from Chad-Henry Galler-Sojourner ( www.bearingwitnessadmissions.com )

- Remember what’s really important : Sometimes the processing of your trauma can be more important than the college acceptances — and that’s ok. If a college doesn’t accept you because you mention mental health issues, sexual assault, or traumatic life experiences, in my opinion, they don’t deserve to have anyone on their campus, much less survivors. Take your hard-earned lived experiences elsewhere. The stigma of being assaulted, abused, or having mental health issues, is a blight on our society. That said, be aware of any potential legal issues as admissions readers are mandated reporters in some states.

- Consider using the Additional Info Section : If you do decide you want to share your story — or you need to because of needing to explain grades, missed school, or another aspect of your application or transcript, don’t feel compelled to write about your trauma, disability, mental health, or addiction in the main personal essay. Instead, we encourage you to use the Additional Info Essay if you want to share (or if you need to share to explain the context of your application). Your main common app essay should be about something that is important to you and should reveal some aspect of who you are. To us (and many applicants), your trauma, disability, mental issues, or addiction doesn’t define you. It isn’t who you are and it isn’t a part you want to lead with.

Putting some other aspect of who you are first in your main essay and putting trauma, addiction, mental health issues, or disability in the Add’l Info Essay is a way to reinforce that those negative experiences in your life don’t define you, and that your recovery or your learning to accommodate for it has relegated that aspect of their experience to a secondary part of who you are.

- You CAN use your Common App essay if you want: IF you feel like recovery from the trauma or learning to handle your circumstances does define you, then there is no reason you can’t put that aspect of who you are forward in the main personal essay. If the growth that stemmed from the crisis is central to your narrative, then it can be a recovery, or an “overcoming” story. It’s a positive look at your strengths and how you achieved them. If you want to place your recovery story front and center in the primary essay, that’s an appropriate choice.

- Write from a place of healing : Some colleges fear liabilities. So, wherever you decide to put your essay in your application, make sure you are presenting your situation in a way that centers how you have dealt with it and moved forward. That doesn’t mean it’s over and everything is all better for you, but you need to write from a place of healing; in essence, “write from scars, not wounds.” (we can’t take credit for that metaphor, but we love it)

- M ake sure your first draft is a free draft. With any topic, it can be hard to stare at a blank page and not feel pressure to write perfectly. This can be doubly true when addressing a tough topic. For your first draft, approach it as a free write. No pressure. No perfection. Just thoughts and feelings. Even if you don’t end up using your essay as a personal statement or in the additional info section, it can be useful to sit and write it out.

- Establish an anchor. Anything that makes you feel safe while you’re writing and exploring your thoughts and experiences. Have that nearby. It can be a candle, an image, a pet, a stuffed animal.

- Check-in with how you are feeling.

- Pay attention to your body and what it’s telling you.

- Take breaks

- Go for walk

- Talk to someone who makes you feel safe

- Remember this kind of essay is NOT a reflection of you. It is only part of your story. (Ashley Lipscomb & Ethan Sawyer, “Addressing Trauma in the College Essay,” NACAC 2021)

- Who supported you in the aftermath of the experience? What did you appreciate about their support and what did you learn about how you would support others?

- Did your self-perception change after the experience? How has your self-perception evolved or grown since?

- How did you cultivate the strength to move through your experience?

- What about how you dealt with the experience makes you most proud?

- Remember that all writing is a two-way street and should serve you and the reader : All writing leaves an emotional impression or residue with the reader. This is especially true with personal essays. Good writers are able to look at their writing and understand how it can serve themselves (that sweet, sweet catharsis) while still meeting the reader halfway. This can be particularly challenging on the college essay, where your goal is to be both personally honest and to help an AO see why you would be a wonderful addition to their school’s student community. When you’re writing, be cognizant of your reader – tell your story

- Shield your writing itself from excessive negativity : When writing about difficult experiences, it can be easy for the writing itself (your phrasing, your diction) to become saturated with a tone of hardship and sorrow. This kind of writing can be hard to read and can get in the way of the underlying story about growth, maturity, or self-awareness. Push yourself to weed out any excessive “negativity” in your writing – look for more neutral ways of stating the facts of your situation. If you’re comfortable, ask a trusted reader to read your essay and point out the places where language seems too negative. Think of ways to rephrase or rewrite.

- Think of your application — and therefore your essay — kind of like a job application. Sure, it’s more personal than a job occupation, but it’s not necessary to share every detail. Focus on the relevant information that validates the power of your journey and overcoming your challenges. Focus on the overcoming.

A framework for writing well about trauma and difficulty: “More Phoenix, Fewer Ashes”

Here’s a framework that we think you could apply to any essay topic about a traumatic experience or challenge. This is not a one-size-fits-all framework, but it should help you avoid the biggest pitfalls in writing about challenging topics.

The framework is called “More Phoenix, Fewer Ashes.” The metaphor actually comes from one of our parents who used to be active on A2C back when her kid was applying to college; she took it down in her notes at a Wellesley info session. In short, however, the idea is to pare down the “ashes” (the really hard details about the situation, past or present) to focus on who you’ve become as a result.

- Address your issue or circumstance BRIEFLY and be straightforward. Don’t dwell on it.

- Next, focus on what you did to take care of yourself and how you handled the situation. Describe how you’ve moved forward and what you learned from the experience.

- Then, write about how you will apply those lessons to your future college career and how you plan to help others with your self-knowledge as you continue to help yourself as you learn more and grow.

- Show them that, while you can’t control what happened in the past, you’ve taken steps to gain control over your life and you’re prepared to be the college student you can be.

- Remember to keep the focus on the positives and what you learned from your experiences.

- Make sure your essay is at least 80% phoenix, 20% ashes. Or another way to put this is, tell the gain, not the pain.

- The ending, overall impression should leave a positive feeling.

- Consider adding a “content warning or trigger warning” at the beginning of your essay, especially if it deals with sexual violence or suicide. You can simply say at the top: Content Warning: this essay discusses sexual violence (or discussion of suicide). This way the reader will know if they need to pass your essay along to someone else to read.

Use that checklist/framework to read back through your essay. In particular, do a spot check with the 80/20 phoenix/ashes rule. Make sure to focus on growth!

Good luck and happy writing,

AdmissionsMom and McNeilAdmissions ( www.McNeilAdmissions.com )

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

I agree with both of You! When we experience a traumatic event, it can be difficult to share our experiences with others. We may feel like we are the only ones who can understand what we went through. We may feel like we are the only ones who can help ourselves heal. But sharing our experiences with others can help us heal and can help prevent further trauma. Although, for me, it’s ok to share. If you can’t, then there’s nothing bad about that. After all, it’s difficult to get back to your dark past.

I love your perspective. Thank you for sharing your thoughts here!

Do you think if you write about a parent who was abusive, they can somehow contact the parent or something? I don’t wanna get in any trouble.

They might have to because of their state laws. I’d research that and talk to your school counselor.

As someone who works closely with high school students, I will definitely be sharing your article with them. It’s a valuable resource that can help them navigate this important aspect of the college application process with confidence and integrity.

Leave A Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Presidential Search

- Editor's Pick

In Photos: Harvard’s 373rd Commencement Exercises

Rabbi Zarchi Confronted Maria Ressa, Walked Off Stage Over Her Harvard Commencement Speech

Former Harvard President Bacow, Maria Ressa to Receive Honorary Degrees at Commencement

‘A’ Game: How Harvard Recruits its Student-Athletes

Interim Harvard President Alan Garber Takes the Political Battle to Washington

College Essays and the Trauma Sweetspot

Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. Reflect on a time when you questioned or challenged a belief or idea. Discuss a period of personal growth and a new understanding of yourself or others. If all else fails, explore a background, identity, interest, or talent so profound that not doing so would leave our idea of you fundamentally incomplete.

Exactly the sort of small talk you want to make with strangers.

American college essays — frequently structured around prompts like the above — ask us to interrogate who we are, who we want to be, and what the most formative experiences of our then-short lives are. To tell a story, to reveal ourselves and our identity in its entirety to the curious gaze of admissions officers — all in a succinct 650 words.

Last Thursday, The Crimson published “ Rewriting Our Admissions Essays, ” an intimate reflection by six Crimson editors on the personal statements that got them into Harvard. Our takeaway from this exercise is that our current essay-generating ethos — the topics we choose or are made to choose, the style and emphasis we apply — is imperfect at best, when not actively harmful.

The American admissions process rightly grants students broad latitude to write about whatever they choose, with prompts that emphasize personal experience, adversity, discovery, and identity — features often distort student narratives and pressure students to present themselves in light of their most difficult experiences.

When it comes to writing, freedom is good — great even! The personal statement can be a powerful vehicle to convey an aspect of one’s identity, and students who feel inclined to do so should take advantage of the opportunity to write deeply and candidly about their lives; the variety of prompts, including the possibility to craft your own, facilitate that. We have no doubt that some of our peers had already pondered, or even lived in the shadow of, the difficult questions posed by the most recurrent essay prompts; and we know the essay to be a fundamental part of the holistic, inclusive admissions system we so fervently cherish . Writing one’s college essay, while stressful, can ultimately prove cathartic to some and revealing to others, a helpful exercise in introspection amid a much too busy reality.

Yet we would be blind not to notice the deep, dark nooks where the system that demands such introspection tends to lead us.

Both the college essay format — short but riveting, revealing but uplifting, insightful but not so self-centered that it will upset any potential admissions counselor — and the prompts that guide it push students towards an ethic of maximum emotional impact. With falling acceptance rates and a desperate need to stand out from tens of thousands of applicants, students frequently feel the need to supply the sort of attention-grabbing drama that might just push them through.

But joyful, restful days don’t make for great stories; there are few, if any, plot points in a stable, warm relationship with a living, healthy relative. Trauma, on the other hand — homophobic or racist encounters that leave one shaken, alcoholic parents, death, loss and scarring pain — makes for a good story. A Harvard-worthy story, even.

For students who have experienced genuine adversity, this pressure to package adversity into a palatable narrative can be toxic. The essay risks commodifying hardship, rendering genuinely soul-molding experiences like suffering recurrent homelessness or having orphaned grandparents into shiny narrative baubles to melt down into a Harvard degree. It can make applicants, accepted or not, feel like their admissions outcomes are tied to their most vulnerable experiences. The worst thing that ever happened to you was simply not enough, or alternatively, it was more than enough, and now you get to struggle with traumatized-imposter syndrome.

Moreover, students often feel compelled to end their essays about deep trauma with a statement of victory — a proclamation that they have overcome their problems and are “fit for admission.” Very few have figured life out by age 18. Trauma often sticks with people far longer, and this implicit obligation may make students feel like they “failed” if the pain of their trauma resurfaces during college. Not every bruise heals and not all damage can be undone — but no one wants to read a sob story without a redemption arc.

A similar dynamic is at play in terms of the intensity of the chosen experience: Students feeling for ridges of scars to tear up into prose must be careful to avoid cuts too deep or too shallow. Their trauma mustn’t appear too severe: No college, certainly not Harvard, wants to admit people who could trigger legal liabilities after a bad mental health episode . That is the essay’s twisted pain paradox — students’ trauma must be compelling but not too serious, shocking but not off-putting. Colleges seek the chic not-like-other-students sort of hurt; they want the fun, quirky pain that leaves the main character with a new refreshing perspective at the end of a lackluster indie film. Genuine wounds — the sort that don’t heal overnight or ever, the kind that don’t lead to an uplifting conclusion that ties in beautifully with your interest in Anthropology — are but lawsuits in the waiting .

For students who have not experienced such trauma, the personal essay can trap accuracy in a tug of war with appealing falsities. The desire to appear as a heroic problem-solver can incentivize students to exaggerate or misrepresent details to compete with the compelling stories of others.

We emphatically reject these unspoken premises. Students from marginalized communities don’t owe college admissions offices an inspirational story of nicely packaged drama. They should not bear a disproportionate burden in proving their worthiness.

Why, then, do these pressures exist? How can we account for the multitude of challenging experiences people have without reductionist commodification? How do you value the sharing of deeply personal struggles without incentivizing every acceptance-hungry applicant to offer an adjective-ridden, six-paragraph attempt at psychoanalyzing their terrible childhood?

We don’t have a quick fix, but we must seek a system that preserves openness and mitigates perverse pressures. Other admissions systems around the world, such as the United Kingdom’s UCAS personal statement, tend to emphasize intellectual interest in tandem with personal experience. The Rhodes Scholarship, citing an excessive focus on the “heroic self” in the essays it receives, recently overhauled its prompts to focus more broadly on the themes “self/others/world.” We should pay attention to the nature of the essays that these prompts inspire and see, in time, if their models are worth replicating.

In the meantime, students should understand that neither their hurt nor their college essay defines them — and there are many ways to stand out to admissions officers. If it feels right to write about deeply difficult experiences, do so with the knowledge that they have far more to contribute to a college campus than adversity and hardship.

The issue is not what people can or should write about in their personal statements. Rather, it’s how what admissions officers expect of their applicants distorts the essays they receive, and how the structure of American college admissions can push toward garment-rending oversharing. We must strive for an admissions culture in which students feel truly free to express their identity — to tell a story they want to share, not one their admissions officers want them to. A system where students can feel comfortable that any specific essay topic — devastating or cheerful — will not place them slightly ahead or behind in the mad, mad race toward that cherished acceptance letter.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Letter of Recommendation

What I’ve Learned From My Students’ College Essays

The genre is often maligned for being formulaic and melodramatic, but it’s more important than you think.

By Nell Freudenberger

Most high school seniors approach the college essay with dread. Either their upbringing hasn’t supplied them with several hundred words of adversity, or worse, they’re afraid that packaging the genuine trauma they’ve experienced is the only way to secure their future. The college counselor at the Brooklyn high school where I’m a writing tutor advises against trauma porn. “Keep it brief , ” she says, “and show how you rose above it.”

I started volunteering in New York City schools in my 20s, before I had kids of my own. At the time, I liked hanging out with teenagers, whom I sometimes had more interesting conversations with than I did my peers. Often I worked with students who spoke English as a second language or who used slang in their writing, and at first I was hung up on grammar. Should I correct any deviation from “standard English” to appeal to some Wizard of Oz behind the curtains of a college admissions office? Or should I encourage students to write the way they speak, in pursuit of an authentic voice, that most elusive of literary qualities?

In fact, I was missing the point. One of many lessons the students have taught me is to let the story dictate the voice of the essay. A few years ago, I worked with a boy who claimed to have nothing to write about. His life had been ordinary, he said; nothing had happened to him. I asked if he wanted to try writing about a family member, his favorite school subject, a summer job? He glanced at his phone, his posture and expression suggesting that he’d rather be anywhere but in front of a computer with me. “Hobbies?” I suggested, without much hope. He gave me a shy glance. “I like to box,” he said.

I’ve had this experience with reluctant writers again and again — when a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously. Of course the primary goal of a college essay is to help its author get an education that leads to a career. Changes in testing policies and financial aid have made applying to college more confusing than ever, but essays have remained basically the same. I would argue that they’re much more than an onerous task or rote exercise, and that unlike standardized tests they are infinitely variable and sometimes beautiful. College essays also provide an opportunity to learn precision, clarity and the process of working toward the truth through multiple revisions.

When a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously.

Even if writing doesn’t end up being fundamental to their future professions, students learn to choose language carefully and to be suspicious of the first words that come to mind. Especially now, as college students shoulder so much of the country’s ethical responsibility for war with their protest movement, essay writing teaches prospective students an increasingly urgent lesson: that choosing their own words over ready-made phrases is the only reliable way to ensure they’re thinking for themselves.

Teenagers are ideal writers for several reasons. They’re usually free of preconceptions about writing, and they tend not to use self-consciously ‘‘literary’’ language. They’re allergic to hypocrisy and are generally unfiltered: They overshare, ask personal questions and call you out for microaggressions as well as less egregious (but still mortifying) verbal errors, such as referring to weed as ‘‘pot.’’ Most important, they have yet to put down their best stories in a finished form.

I can imagine an essay taking a risk and distinguishing itself formally — a poem or a one-act play — but most kids use a more straightforward model: a hook followed by a narrative built around “small moments” that lead to a concluding lesson or aspiration for the future. I never get tired of working with students on these essays because each one is different, and the short, rigid form sometimes makes an emotional story even more powerful. Before I read Javier Zamora’s wrenching “Solito,” I worked with a student who had been transported by a coyote into the U.S. and was reunited with his mother in the parking lot of a big-box store. I don’t remember whether this essay focused on specific skills or coping mechanisms that he gained from his ordeal. I remember only the bliss of the parent-and-child reunion in that uninspiring setting. If I were making a case to an admissions officer, I would suggest that simply being able to convey that experience demonstrates the kind of resilience that any college should admire.

The essays that have stayed with me over the years don’t follow a pattern. There are some narratives on very predictable topics — living up to the expectations of immigrant parents, or suffering from depression in 2020 — that are moving because of the attention with which the student describes the experience. One girl determined to become an engineer while watching her father build furniture from scraps after work; a boy, grieving for his mother during lockdown, began taking pictures of the sky.

If, as Lorrie Moore said, “a short story is a love affair; a novel is a marriage,” what is a college essay? Every once in a while I sit down next to a student and start reading, and I have to suppress my excitement, because there on the Google Doc in front of me is a real writer’s voice. One of the first students I ever worked with wrote about falling in love with another girl in dance class, the absolute magic of watching her move and the terror in the conflict between her feelings and the instruction of her religious middle school. She made me think that college essays are less like love than limerence: one-sided, obsessive, idiosyncratic but profound, the first draft of the most personal story their writers will ever tell.

Nell Freudenberger’s novel “The Limits” was published by Knopf last month. She volunteers through the PEN America Writers in the Schools program.

Addressing Trauma in the College Essay

- October 29, 2020

- 2020-2021 , NACAC

Cody Dailey Victor J. Andrew High School

By the time you read this, many students will have (hopefully!) submitted their college applications and essays. However, with regular decision deadlines still around the corner, I felt it’s still relevant to share some takeaways from a presentation I attended at the 2020 NACAC that addressed trauma in the college essay.

This year has been challenging for students in so many ways. With the global pandemic, needed calls for racial justice, and a highly-polarized election cycle, students have seen and experienced increased levels of trauma. In the college admissions process, oftentimes these traumatic experiences can be displayed or brought to light in a student’s writing sample for applications. In the NACAC session titled, ‘Addressing Trauma in the College Essay Writing Process,’ presenters Ashley Lipscomb and Ethan Sawyer touched on many key recommendations for working with students who have experienced trauma as it pertains to the college essay.

Among the key takeaways, there was a reminder that students should not feel required or pressured into always writing about their challenges. While that is a powerful topic to explore, there are many others, including writing about a passion, an identity, a career, an important object or memory, or even a unique skill or ‘superpower.’ Sometimes students feel pigeon-holed into writing about their traumas, but we should remind them that they own the distribution rights to those moments.

If a student is struggling with what to write about, Ethan shared a phenomenal activity that could be done with individuals, small groups or even an entire class: his “Feelings and Needs Exercise.”

He has students start by making five columns:

- Column 1: Students share challenges they’ve experienced

- Column 2: Students write down the effects that occurred due to that challenge

- Column 3: Students write down feelings associated with those effects

- Column 4: Students write down what they needed/feel they needed to cope with the feelings

- Column 5: Students write what they did action-wise to overcome those feelings

Once they have completed this exercise, it should give students a menu of different options of where they want to go in their writing. He encourages students to ‘star’ important topics or themes. This can also be done by pairing students up in a pair-and-share model, but you must be cautious that students within the class trust one another with these sensitive topics.

Finally, simply affirming and thanking the student for sharing their experience goes a long way. In sharing, students are trusting us with a lot of very personal, traumatic information. In return, we must show them the utmost respect and gratitude for not only valuing our input but also trusting us with this information. To some this might be just an essay to check off the list, but for others it can also be a powerful tool of emotional processing, and we are lucky to be a part of that.

SI Turned New Counselor Institute

Derek Brinkley Columbia College Chicago Sarah Goldman University of Oregon…

You Are Not Alone

Jill Diaz My College Summit Prior to 2020, if you…

Reflections from Two NACAC Conference First Timers

Jessica Avila-Cuevas College of DuPage There is always a first…

- previous post: Reflections from Two NACAC Conference First Timers

- next post: SI Turned New Counselor Institute

The Effects of Childhood Trauma on College Completion

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2022

- Volume 63 , pages 1058–1072, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Natalie Lecy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7472-4448 1 &

- Philip Osteen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4897-1784 1

10k Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study uses the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health to examine the effect of childhood trauma experiences on college graduation rates. A longitudinal mediation path analysis with a binary logistic regression is performed using trauma as a mediator between race, gender, first-generation status and college completion. The analysis reveals that being female and a continuing-generation student are both associated with greater likelihood of graduating college and that trauma mediates the relationship between race, gender, first-generation status and college completion. The authors explore the implications for these findings for policy, practice, and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Trauma Through the Life Cycle: A Review of Current Literature

Adverse childhood experiences and adulthood mental health: a cross-cultural examination among university students in seven countries, childhood trauma history and negative social experiences in college.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Earning a college degree remains one of the most reliable paths to economic, health, and social stability (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2006 ; Sing-Manoux et al., 2010 ; Steptoe et al., 2011 ; U.S. Department of Education, 2018 ; World Health Organization, 2003 ). Despite increasing college enrollment rates in the United States, the social-class achievement gap has actually widened (Page et al., 2019 ; Stephens et al., 2014 ). First-generation students are distinctly disadvantaged while attempting to access and navigate the system of higher education (Stephens et al., 2014 ). Given the disproportionate graduation rates of first-generation students, further research is warranted in exploring the factors which contribute to this phenomenon; including the effects of childhood trauma.

Incipient research continually unveils the expansive net trauma casts on later functioning in life (Metzler et al., 2016 ; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012 ). Experiencing childhood trauma correlates with diminished social, emotional, and economic stability into adulthood (Metzler et al., 2016 ; Sansone et al., 2012 ; Zielinski, 2009 ). Despite the budding focus on the effects of childhood trauma on socioemotional outcomes in adults, there is a vast gap in knowledge on the role childhood trauma plays on college achievement rates. This study aims to explore the effect of childhood trauma experiences on later college completion rates among first-generation status, gender, and race.

First-Generation Students and Higher Education

First-generation students are defined as students without a parent having a college degree, versus continuing-generation students who have at least one parent with a college degree (Stephens et al., 2014 ). First-generation students comprise between two-fifths and three-fifths of all college students (Cataldi et al., 2018 ; Skomsvold, 2015 ). First-generation students are more likely to come from lower-socioeconomic households and are more likely to be a racial minority than their continuing-generation counterparts (Horn & Nunez, 2000 ; Jack, 2019 ; Sandoz et al., 2017 ). These students can face a plethora of obstacles while attempting to navigate higher education. They are more likely to be working part- or full-time jobs, be enrolled in less credits, feel unwelcome on college campuses, and struggle to create connections with both faculty and their continuing-generation peers (Beegle, 2003 ; Sandoz et al., 2017 ; Tate et al., 2015 ; Wilson & Gibson, 2011 ; Wilson et al., 2012 ).

Obtaining a college degree increases positive outcomes in nearly every facet of life including economic stability, occupational stability, physical health, and mental health (Tate et al., 2015 ). In regards to health, the benefits of a college degree are vast. Health disparities are wide for college graduates compared to high school graduates; those without college degrees having increased risk for heart disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer, and increased infant mortality rates (World Health Organization, 2003 ; Zimmerman et al., 2015 ). Average life expectancy is increased by nine years for college graduates compared to high school graduates (Zimmerman et al., 2015 ).

Not surprisingly, income and education level are highly correlated (Sandoz et al., 2017 ). The median income for high school graduates is $31,800, compared to $50,000 for college graduates and $64,000 for those with graduate degrees (U.S. Department of Education, 2018 ). Obtaining a college degree improves wages and increases access to careers which support higher quality of life with great access to health insurance, increased benefits such as retirement plans, and friendlier work environments (Bloom, 2009 ). Considering the myriad of health, economic, and social benefits a higher education provides, it is important that students from all backgrounds have equal access and chances of graduating. Unfortunately, first-generation students remain disadvantaged while striving towards the great equalizer of a college degree (Jack, 2019 ).

Race and Higher Education

White privilege provides pervasive advantages throughout American culture including our systems of higher education (Diangelo, 2018 ; Fischer, 2010 ; Jack, 2019 ). Racial disparities in higher education are evident by viewing the lower rates at which students of color apply, enroll, and graduate from college (Jones & Howard, 2020 ; NCES, 2019 ). Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous students may experience increased barriers while attending college and are at greater risk for dropping out compared to their White counterparts (Fischer, 2010 ; NCES, 2019 ). Achievement gaps for students of color, especially Black students, are worsened when attending predominately white institutions (Beasely et al., 2016 ). Stereotype threat, social life satisfaction, and campus racial climates have been identified as contributors toward racial disparities in higher education (Fischer, 2010 ).

In order to address systemic inequalities embedded in education, it would be fruitful to uncover additional contributing factors to their college completion rates. According to the CDC ( 2019 ), people of color are more likely to experience adverse childhood experiences at higher rates than their White counterparts. This raises the question on whether childhood trauma could contribute to college graduation rates by race.

Gender and Higher Education

Women increasingly enroll, attend, and graduate from college at higher rates than their male counterparts (NCES, 2013 ). Roughly, they comprise 60% of college students across the United States (NCES, 2013 ) and exceed this proportion among Black and American Indian students (Conger & Dickson, 2017 ; NCES, 2013 ). Women tend to have higher grade point averages during high school and are more responsive to supportive services such as financial aid, case management, and mentoring (Conger & Dickson, 2017 ). The growing gender imbalance leaves academic institutions in a unique position to determine how to better support their male students. Female representation in academic settings have been steadily growing since the 1970s (Conger & Dickson, 2017 ) but the shift to explicitly creating male preference during college recruitment and retention is nuanced. In an attempt to better understand the dwindling rates of college completion among males, it would be helpful to understand what qualities or experiences contribute to their success or failure. Pertinent to this discussion is unveiling the role of childhood adversities on college graduation rates by gender.

Childhood Trauma

Emerging research is illuminating the ruminating effects of experiencing childhood trauma on outcomes well into adulthood. This research reveals a negative impact on health, social, mental health, and employment outcomes (Metzler et al., 2016 ; Sansone et al., 2012 ; Zielinski, 2009 ). Surprisingly, little research on childhood trauma and its effect on higher education outcomes exists. Given the alarming rates children in the United States are exposed to trauma, it appears an essential area to explore.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that two out of three U.S. children experience at least one potentially traumatic event prior to their 18th birthday with approximately a quarter of those children experiencing two or more potentially traumatic events prior to the age of 18 (CDC, 2019 ). Experiencing trauma during childhood has a titanic impact on one’s later ability to live a healthy, fulfilling adult life. Exposure to childhood trauma links to poorer physical health, poorer mental health, and greater risky behaviors in later life (CDC, 2019 ; Metzler et al., 2016 ).

The landmark study of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), authored by Felitti et al. ( 1998 ) and carried out by the Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente, created awareness around the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences while also shedding a light on the lifelong toll of childhood trauma (CDC, 2019 ). Since the Felitti et al. ( 1998 ) study revealing the complexity of the long-term health impacts stemming from childhood trauma, research in this area continues to emerge. Through this budding research we are at the threshold of understanding the lingering presence of childhood trauma pervasive in multiple domains of adult life. Areas influenced by childhood trauma include attaining a high school degree, employability, earnings, health outcomes, and interpersonal relationships (Metzler et al., 2016 ).

Trauma and Health Outcomes

The impact of multiple childhood traumas is staggering. The exponential negative impact on long-term health outcomes is known as the dose–response relationship (Flaherty et al., 2013 ; Metzler et al., 2016 ). For example, those who experience exposure to four or more different types of trauma have a 12-fold risk increase for depression, suicide attempts, and substance use disorders compared to those without such exposure (Felitti et al., 1998 ). Childhood exposure to multiple traumas also increases a person’s risk for sexually transmitted diseases, smoking, obesity, heart disease, cancer, liver disease, skeletal fractures, involvement in abusive relationships, and premature mortality by 19 years of age (Brown et al., 2009 ; Felitti et al., 1998 ; Gilbert et al., 2010 ).

Trauma’s Impact on the Brain

In addition to illuminating the impact of ACEs on health outcomes, research connects the impact early trauma has on brain development (Brown et al., 2009 ; Felitti et al., 1998 ; Gilbert et al., 2010 ; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012 ). Early childhood traumas and exposure to chronic stress impact how the brain develops, often blocking the development of neuropathways from the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex (Babcock, 2014 ; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012 ). The inability to form neuropathways to the prefrontal cortex impacts a range of functions, including planning, task execution, memory, attention span, the ability to learn new skills, and the ability to anticipate events (Shonkoff & Garner, 2012 ; Shonkoff et al., 2009 ). Diminished executive functioning skills affect one’s ability to function in all areas of life, which can include impairment in interpersonal relationships, parenting, career stability, educational attainment, and financial planning (Babcock, 2014 ).

Socioeconomic Outcomes

The ability to obtain and retain employment correlates to childhood trauma exposure (Sansone et al., 2012 ). Adults with childhood trauma experiences are twice as likely to be unemployed compared to adults without childhood trauma (Metzler et al., 2016 ; Zielinski, 2009 ). Experiencing childhood trauma puts individuals at a higher risk for having economic instability as an adult (Zielinski, 2009 ). This includes a greater risk of being in households in which other adults are likely to lose their jobs (Zielinski, 2009 ). Experiencing childhood trauma also increases one’s later risk as an adult to live below the poverty line and to be without health insurance (Zielinski, 2009 ). Since these studies are correlational, it is difficult to pinpoint the cause of economic instability. However, given that childhood trauma experiences impair physical health, mental health, and brain development, it is possible the weight of these factors contributes to the inability to flourish after experiencing multiple childhood traumas. While research consistently demonstrates that childhood trauma negatively impacts adult employability, some speculate that different types of trauma have different effects on individual functioning. For example, some research indicates that experiencing sexual abuse and witnessing violence have a greater negative effect on employability than experiencing physical abuse or neglect as a child (Sansone et al., 2012 ). Research has not yet isolated the mechanisms behind those connections.

Additionally, children who experience childhood trauma are less likely to graduate from high school than their counterparts (Metzler et al., 2016 ). Risk of high school non-completion correlates with the number of adverse childhood experiences experienced (Metzler et al., 2016 ). The more categories of childhood trauma experienced, the less likely a person is to have graduated from high school (Metzler et al., 2016 ). Unfortunately, research on the effects of childhood trauma past high school is limited. Considering the vast effects childhood trauma can have on later outcomes, particularly the executive functioning skills of the brain, there is suggestive evidence that increased childhood trauma could correlate with college completion. Given the tremendous benefits of earning a college degree, it would be helpful to better understand the relationship between childhood trauma and college graduation rates.

Need for Current Research

Emerging research on the effects of childhood trauma throughout the lifetime is linking trauma with poorer social, emotional, and health outcomes. A connection between childhood trauma and decreased high school graduation rates has been demonstrated (Metzler et al., 2016 ). Surprisingly, little research has explored the relationship of childhood trauma with outcomes in higher education. Considering the pervasiveness of experiencing childhood adversities, it appears crucial to understand its effects on college degree attainment. Exploring these factors could provide valuable insight into the longer-term obstacles created by childhood trauma.

Gaining information on the effects of childhood trauma on higher education outcomes will provide insight into developing interventions to increase successful college outcomes. If a connection between childhood trauma and college outcomes exist, it could warrant the bridging of trauma informed approaches with environments of higher education. Budding research suggests primary and secondary education environments utilizing trauma-informed approaches increase educational outcomes (Herrenkohl et al., 2019 ; SAMSHA, 2014 ). If rates of childhood adversities correlate with later college graduation rates by generational status, race, or gender it would contribute to the knowledge base on how to strategically target supports for each subset.

The present study aims to increase understanding on how experiencing childhood trauma affects college completion. This study aims to answer the questions: (1) Are race, gender, first-generation status, and trauma predictors of college outcomes? (2) Does trauma mediate the relationships between race, gender, first-generation status, and college graduation? To answer these questions, data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health was selected because of its robust information provided from multiple timepoints over the course of fourteen years (more information below).

Study Procedures

This current study used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (AAD Health) which was a nationally representative sample of U.S. youth beginning in the 1994–1995 school year when they were in grades 7–12. The original AAD Health study followed the youth through three more waves including Wave II in 1996, Wave III from 2001–2002, and Wave IV in 2008. The AAD Health study gathered social, emotional, health, and economic data from youth, their parents, and their schools. During Wave I, more than 90,000 students in 7th through 12th grades completed in-school surveys. The researchers then selected a random sample of 20,745 from those 90,000 students for in-home interviews. Their primary parent/guardian also completed an in-home interview; school administrative data also was provided. Wave IV (n = 15,701, current ages 24–32) consisted of an in-home interview, supplemented by lab tests. All respondents who participated in the original Wave I in-home interviews were eligible for Wave IV in-home interviews. Eighty percent of the eligible participants participated in the final Wave IV in-home interviews. For full details of this longitudinal study, see Harris and Udry ( 2018 ).

This dataset is well-suited to answer the research questions outlined above due to the comprehensive nature of the AAD Health dataset including topics related to race, gender, childhood trauma, and college attainment. It also offers advantages over one-time cross-sectional surveys since it captured participant data at four separate time points using a mix of surveys, in-home participant interviews, parental interviews, and administrative data.

Participants

The present study consisted of data collected in Waves I, II, III, and IV. For the present study, the authors limited participants to those who completed each wave of the interviews (Wave I, II, III, and IV) (n = 5114). The sample was further narrowed to include participants who entered four-year colleges. Additionally, only participants who identified as Black or White were included in the final sample. Race was originally assessed as White, Black or African American, American Indian or Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander , or Other (Harris & Udry, 2018 ). However, American Indian, Native American, and Asian/Pacific Islander groups did not have sufficient sample sizes for subgroup analysis and were thus removed, bringing the final sample to n = 2917. Among the participants who entered college, 58.3% identified as female and 41.7% as male. Regarding race, 77.6% of the participants identified as White or Caucasian and 22.4% indicated their primary identification as Black or African American. First-generation students comprised 49.2% of the sample and 50.8% were considered continuing-generation students. In the final interview, the age range was from 24 to 32 years-old (M = 26.9 years).

Model Variables

The primary outcome, college completion, was defined by the authors as whether participants graduated from a four-year-college. This information was obtained from participants during Wave IV, in-home interviews. This variable was transformed into a binary variable with the categories defined as did not complete college = 0; or completed college = 1.

Childhood trauma was defined as adverse experiences experienced by the participant prior to the age 18. All four waves of AAD Health assessed different trauma experiences, and a total of 17 questions assessed the experiences prior to the age of 18. Questions included assessments of home life such as whether their parents were depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal, whether the participant experienced neglect or abuse. Trauma questions also included experiences that could be external to the home, such as experiencing an assault, or witnessing violence. Sample items include: “Before your 18th birthday, how often did a parent or adult caregiver hit you with a fist, kick you, or throw you down on the floor, into a wall, or down a stairs?”, “Have you saw a shooting/stabbing of person?”, and “Had a knife/gun pulled on you?”. If participants indicated they experienced any dose of the event, they were provided a score of one for that response. Responses were summated with higher numbers indicating more trauma experiences . Trauma questions were selected to mirror CDC’s ( 2019 ) framework around Adverse Childhood Experiences and their Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (CDC BRFSS, 2021). Trauma scores were summed to capture the dose–response relationship demonstrated in previous research, which suggests multiple childhood traumas have an exponential negative impact on long-term outcomes (Flaherty et al., 2013 ; Metzler et al., 2016 ).

Gender, generational status, and race are the primary predictors in the model. Gender was a binary category coded as female = 0 or male = 1 . First-generation was a binary category coded to include participants who had at least one parent graduate from college (continuing-generation) = 0 versus participants who didn’t have a parent who graduated from college (first-generation) = 1. Race was originally assessed as White, Black or African American, American Indian or Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander , or Other (Harris & Udry, 2018 ). Race was recoded into a binary category of White = 0 or Black = 1 because all other categories did not have sufficient sample sizes for subgroup analyses.

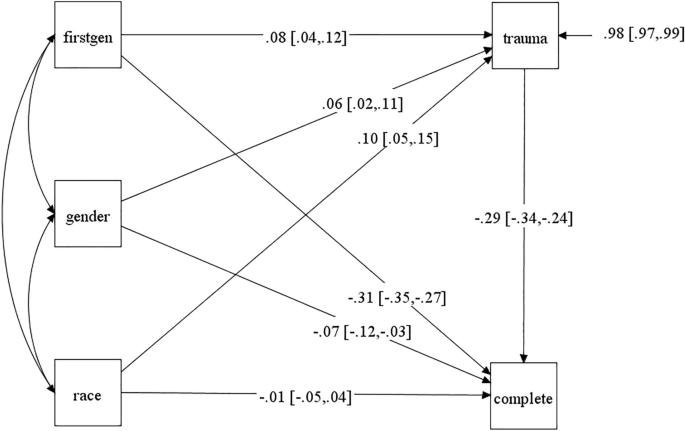

A longitudinal binary logistic regression mediation path analysis, a subset of structural equation modeling, was performed using Mplus statistical software (version 8.3; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017 ) using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR). The model was tested using race, gender, and first-generation status as primary predictors of college completion, and trauma as the mediating variable. The model was just-identified and demonstrated perfect fit to the data.

The study sample was predominantly female (58.3%), and White (77.6%). Generational status was closely distributed with first-generation students representing 49.2% of the sample and 50.8% continuing-generation students. Females graduated at higher rates compared to their male counterparts (52.5% and 46.8% respectively). In the sample, 44.4% of Black students completed college, compared to 51.2% of White students. A starker disproportionality was observed based on generational status, with only 38.0% of first-generation students graduating compared to 68.0% of continuing-generation students (Table 1 ).

Trauma experiences ranged from 0 to 9 ( Mean = 1.63, SD = 1.56). On average, males reported 1.67 ( SD = 1.58) trauma experiences compared to 1.60 ( SD = 1.55) for females. White students had an average of 1.45 ( SD = 1.49) trauma experiences, whereas Black students reported an average of 2.10 ( SD = 1.69) trauma experiences. First-generation students reported more trauma experiences ( Mean = 1.91, SD = 1.64) than their continuing-generation students ( Mean = 1.31, SD = 1.40) (Table 2 ).

Results for College Completion

Odds ratios were calculated for direct effects only. To ensure comparisons of direct and indirect effects, our reporting focuses on the linear regression coefficients. For clarity of interpretation regarding odds ratios, negative linear regression coefficients less than one indicate a decreased likelihood of this event happening. Odds ratio of more than one indicates an increased likelihood of this event happening.

Direct Effects

Whether the student identified as White or Black was not a statistically significant predictor of whether they graduated from college (b = − 0.01, p = 0.824). Students’ gender was a statistically significant predictor of whether the student graduated from college. Male students were less likely to graduate from college than their female counterparts (b = − 0.07, p = 0.002). Whether the student was a first-generation student or a continuing-generation student was a statistically significant predictor of whether they would graduate from college. First-generation students were less likely to graduate from college than their continuing-generation counterparts (b = − 0.31, p ≤ 0.001). Experiencing childhood trauma was a statistically significant predictor of whether they would graduate from college (b = − 0.29, p ≤ 0.001). The higher the number of trauma events experienced, the less likely the participant was to graduate from college.

Indirect Effects

There was a statistically significant indirect effect of race on college completion through childhood trauma experiences corresponding to a full mediation of the relationship between race and college completion (b = − 0.03, p ≤ 0.001). This indicates that trauma serves as a full mediator between the relationship of race and college completion, suggesting this relationship is expressed by Black students’ stronger connection to childhood trauma than White students. There was a statistically significant indirect effect of gender on college graduation through childhood trauma experiences (b = − 0.02, p = 0.006). Trauma serves as a partial mediator between gender and college completion, indicating that a portion of this relationship is manifested in the gender-trauma connection. This means that the reduced likelihood of college completion for males is partially explained by their stronger connection to trauma than females. There was a statistically significant indirect effect of generational status on college graduation through childhood trauma experiences. Trauma serves as a partial mediator to the relationship between generational status and college completion, indicating that a portion of this relationship is manifested in the first-generation-trauma connection (b = − 0.02, p = 0.001). This means the reduced likelihood of college completion for first-generation students is partially explained by their stronger connection to trauma than continuing-generation students (see Table 3 ; Fig. 1 ). Direct and indirect effects can be combined to obtain an estimate of the total effect between race, gender, generational status, and childhood trauma experiences and college graduation. Based on the results of the model, the total effect is 20.2% (R 2 = 0.202, p < 0.001).

The Mediation of College Completion (standardized coefficients and 95% CI’s)

The findings from the present study suggest experiencing childhood trauma plays a powerful role in college outcomes. The findings suggest that first-generation, male, and Black students experience worse outcomes in higher education as their childhood trauma experiences increase. Considering first-generation, Black, and male students are at increased risk of dropping out of college than their peers (CFFGSS, 2018 ; NCES, 2019 ), it is useful to uncover contributing barriers to their success and it appears that childhood trauma may play an important role in their academic trajectories.

First-generation students vary greatly in their demographics and experiences. On average, they tend to graduate at rates 14–15% lower than their continuing-generation counterparts (DeAngelo et al, 2011 ; Postsecondary National Policy Institute, 2021 ). First-generation students are more likely to be older, have dependents, identify as a student of color, work more hours, have less income, and attend school part-time compared to their continuing-generation peers (CFFGSS, 2018 ; NCES, 2019 ). Academic literature has long focused on a variety of obstacles contributing to the college trajectory of first-generation students but thus far, the effects of childhood trauma has been underexamined. This study indicates the reduced likelihood of college completion for first-generation students is partially explained by their stronger connection to trauma than continuing-generation students.

Students of color, especially Black students, face substantial obstacles to successfully navigating higher education. Black students face greater barriers in accessing higher education than Whites, including a greater likelihood of living in poverty (Kaiser Foundation, 2017 ). Once enrolled in college Black students may experience difficulties establishing a sense of belonging, forming social networks, and overcoming racism (Fischer, 2010 ). Analyzing graduation rates through childhood trauma experiences was especially pertinent for Black students, who did not have statistically significant differences in graduation rates compared to their White counterparts when examining direct effects. However, when using childhood trauma experiences as a mediator, the results indicate trauma serves as a full mediator between the relationship of race and college completion, suggesting this relationship is expressed by Black students’ stronger connection to childhood trauma than White students. In order to address the racial disparities pervasive in many systems of higher education, it is essential to uncover potential contributors toward achievement gaps. The full mediation demonstrated in this study between race, trauma experiences, and graduation rates, indicates a need for the development of policies and interventions addressing the deleterious effects of childhood traumas among Black students on college completion.

Childhood trauma experiences also affect college graduation rates among male students, indicating the reduced likelihood of college completion for males is partially explained by their stronger connection to trauma than females. Overall, female students represent a growing number of the college population with females representing approximately 60% of college campuses (Jacobs, 2002 ). This gender imbalance is a growing concern as college graduation rates for males continue to lag (Jacobs, 2002 ). Research evaluating support services aimed at increasing retention and graduation rates indicate females are more likely to take advantage of both mentoring and financial assistance programs (Angrist et al., 2009 ). Our findings demonstrating the confounding effect of trauma on male graduation rates, warrants further concern on why these students may be left behind. The development of interventions aimed at addressing the negative outcomes of childhood adversity should consider ways to increase engagement among male students.

Limitations

The present study utilized data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health to examine the effect of childhood trauma experiences on college graduation rates. This database is extensive and includes a wide breadth of data points from middle-school into adulthood. However, using any secondary dataset creates limitations regarding which research questions can be asked and results should be interpreted within the context of the limitations of the dataset.

One of the limitations is the grouping of the variable “race”. The original AAD Health dataset categorized race as White, Black or African American, American Indian or Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander , or Other (Harris & Udry, 2018 ). Due to smaller subgroup sizes among American Indians and Asian/Pacific Islanders, they were excluded from the analyses, resulting in a binary variable for race comparing Black versus White students. Postsecondary graduation rates can vary greatly for students in different racial and ethnic groups (NCES, 2019 ) and it would be beneficial for future research to explore differences experienced across racial groups. However, despite limitations the present study still offered insight into the experiences of Black and White students in regards to the differing role of childhood trauma on their college graduation rates. It was important to explore the relationship between race, childhood trauma, and college graduation rates because people of color often experience childhood adversities at higher rates than Whites (CDC, 2019 ).

Another consideration to the present study was the ability to capture childhood trauma experiences. AAD Health did have an extensive set of questions throughout the course of the study that captured a variety of childhood trauma experiences. However, the questions were not standardized or based upon any specific measurement tools. Fortunately, many of the questions paralleled those of the more prominent Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire with the present study also including some experiences that could happen outside of the family (witnessing or experiencing violence).

Implications

The findings from this study increase our knowledge base on the effects of gender, race, first-generation status, and childhood trauma on later college degree completion. The present study indicates that first-generation students, male students, and those who experienced increased childhood trauma are at higher risk of not completing college once enrolled. Experiencing childhood trauma increases the risk of dropping out of college for first-generation students, males, and Black students. These findings suggest targeting interventions which better support increased graduation rates among these groups could be fruitful and have a considerable economic payout long-term. If greater rates of first-generation, Black, and male students graduated college, their earning potential would increase and they would likely experience better physical, social, and emotional well-being.

Future research should explore whether existing school environments are successfully supporting the retention of these students and which interventions are effectually increasing their retention and graduation rates. In order to target future policy and practice efforts, it would be helpful to better understand the experiences of these student groups and what perceived barriers exist. Further, it would be advantageous to better understand if there are existing academic environments or programs supporting these students to thrive and what mechanisms are increasing graduation rates.