Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Developing a Research Question

3.4 Hypotheses

When researchers do not have predictions about what they will find, they conduct research to answer a question or questions with an open-minded desire to know about a topic, or to help develop hypotheses for later testing. In other situations, the purpose of research is to test a specific hypothesis or hypotheses. A hypothesis is a statement, sometimes but not always causal, describing a researcher’s expectations regarding anticipated finding. Often hypotheses are written to describe the expected relationship between two variables (though this is not a requirement). To develop a hypothesis, one needs to understand the differences between independent and dependent variables and between units of observation and units of analysis. Hypotheses are typically drawn from theories and usually describe how an independent variable is expected to affect some dependent variable or variables. Researchers following a deductive approach to their research will hypothesize about what they expect to find based on the theory or theories that frame their study. If the theory accurately reflects the phenomenon it is designed to explain, then the researcher’s hypotheses about what would be observed in the real world should bear out.

Sometimes researchers will hypothesize that a relationship will take a specific direction. As a result, an increase or decrease in one area might be said to cause an increase or decrease in another. For example, you might choose to study the relationship between age and legalization of marijuana. Perhaps you have done some reading in your spare time, or in another course you have taken. Based on the theories you have read, you hypothesize that “age is negatively related to support for marijuana legalization.” What have you just hypothesized? You have hypothesized that as people get older, the likelihood of their support for marijuana legalization decreases. Thus, as age moves in one direction (up), support for marijuana legalization moves in another direction (down). If writing hypotheses feels tricky, it is sometimes helpful to draw them out and depict each of the two hypotheses we have just discussed.

Note that you will almost never hear researchers say that they have proven their hypotheses. A statement that bold implies that a relationship has been shown to exist with absolute certainty and there is no chance that there are conditions under which the hypothesis would not bear out. Instead, researchers tend to say that their hypotheses have been supported (or not). This more cautious way of discussing findings allows for the possibility that new evidence or new ways of examining a relationship will be discovered. Researchers may also discuss a null hypothesis, one that predicts no relationship between the variables being studied. If a researcher rejects the null hypothesis, he or she is saying that the variables in question are somehow related to one another.

Quantitative and qualitative researchers tend to take different approaches when it comes to hypotheses. In quantitative research, the goal often is to empirically test hypotheses generated from theory. With a qualitative approach, on the other hand, a researcher may begin with some vague expectations about what he or she will find, but the aim is not to test one’s expectations against some empirical observations. Instead, theory development or construction is the goal. Qualitative researchers may develop theories from which hypotheses can be drawn and quantitative researchers may then test those hypotheses. Both types of research are crucial to understanding our social world, and both play an important role in the matter of hypothesis development and testing. In the following section, we will look at qualitative and quantitative approaches to research, as well as mixed methods.

Text attributions This chapter has been adapted from Chapter 5.2 in Principles of Sociological Inquiry , which was adapted by the Saylor Academy without attribution to the original authors or publisher, as requested by the licensor, and is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 License .

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define and describe the scientific method.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research.

- Describe the function and importance of an interpretive framework.

- Describe the differences in accuracy, reliability and validity in a research study.

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method and a scholarly interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries, in families that have enlightened family members, and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of six prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scientific scholarship.

Sociological research does not reduce knowledge to right or wrong facts. Results of studies tend to provide people with insights they did not have before—explanations of human behaviors and social practices and access to knowledge of other cultures, rituals and beliefs, or trends and attitudes.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, and exercise habits.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas. This does not mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in collecting and analyzing data in research studies.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. They provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963). Typically, the scientific method has 6 steps which are described below.

Step 1: Ask a Question or Find a Research Topic

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?”

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study crime, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police database, prison information, interviews with criminals, guards, wardens, etc. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research to determine how these resources might be used to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variables (IV) , which are the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV) , which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

Taking an example from Table 12.1, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying related two topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Design and Conduct a Study

Researchers design studies to maximize reliability , which refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what happens to one person will happen to all people in a group or what will happen in one situation will happen in another. Cooking is a science. When you follow a recipe and measure ingredients with a cooking tool, such as a measuring cup, the same results is obtained as long as the cook follows the same recipe and uses the same type of tool. The measuring cup introduces accuracy into the process. If a person uses a less accurate tool, such as their hand, to measure ingredients rather than a cup, the same result may not be replicated. Accurate tools and methods increase reliability.

Researchers also strive for validity , which refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. To produce reliable and valid results, sociologists develop an operational definition , that is, they define each concept, or variable, in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept. By operationalizing the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner. Moreover, researchers can determine whether the experiment or method validly represent the phenomenon they intended to study.

A study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, might define “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” However, one researcher might define a “good” grade as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for “good.” For the results to be replicated and gain acceptance within the broader scientific community, researchers would have to use a standard operational definition. These definitions set limits and establish cut-off points that ensure consistency and replicability in a study.

We will explore research methods in greater detail in the next section of this chapter.

Step 5: Draw Conclusions

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, tabulate or categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss the implications of the results for the theory or policy solution that they were addressing. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, researchers may consider repeating the experiment or think of ways to improve their procedure.

However, even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, these results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Sociologists carefully keep in mind how operational definitions and research designs impact the results as they draw conclusions. Consider the concept of “increase of crime,” which might be defined as the percent increase in crime from last week to this week, as in the study of Swedish crime discussed above. Yet the data used to evaluate “increase of crime” might be limited by many factors: who commits the crime, where the crimes are committed, or what type of crime is committed. If the data is gathered for “crimes committed in Houston, Texas in zip code 77021,” then it may not be generalizable to crimes committed in rural areas outside of major cities like Houston. If data is collected about vandalism, it may not be generalizable to assault.

Step 6: Report Results

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develops as the relationships between social phenomenon are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on empirical data and the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework . While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective , seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge or understanding about the human experience.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects including storytelling. This type of researcher learns through the process and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

Critical Sociology

Critical sociology focuses on deconstruction of existing sociological research and theory. Informed by the work of Karl Marx, scholars known collectively as the Frankfurt School proposed that social science, as much as any academic pursuit, is embedded in the system of power constituted by the set of class, caste, race, gender, and other relationships that exist in the society. Consequently, it cannot be treated as purely objective. Critical sociologists view theories, methods, and the conclusions as serving one of two purposes: they can either legitimate and rationalize systems of social power and oppression or liberate humans from inequality and restriction on human freedom. Deconstruction can involve data collection, but the analysis of this data is not empirical or positivist.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

PSC/SOC 340/JS 504: Social Science Research Methods

- Getting Started

- The Scientific Method

- How to Read Scientific Articles

- Research vs Review Articles

- Quantitative vs Qualitative Research

- Books About Research Process

- Lit Review & Research Question

What is the difference between a theory & a hypothesis?

An example of how to write a hypothesis.

- Research Design

- Research Instrument

- Find Articles, Reports & Documents

- How do I find a Quantitative article?

- Find Statistics

- Find Poll & Survey Results

- Evaluate Your Sources

- Cite Your Sources

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in everyday use. However, the difference between them in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested hypotheses that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis . About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis . Slideshare presentation.

A worker on a fish-farm notices that his trout seem to have more fish lice in the summer, when the water levels are low, and wants to find out why. His research leads him to believe that the amount of oxygen is the reason - fish that are oxygen stressed tend to be more susceptible to disease and parasites.

He proposes a general hypothesis.

“Water levels affect the amount of lice suffered by rainbow trout.”

This is a good general hypothesis, but it gives no guide to how to design the research or experiment . The hypothesis must be refined to give a little direction.

“Rainbow trout suffer more lice when water levels are low.”

Now there is some directionality, but the hypothesis is not really testable , so the final stage is to design an experiment around which research can be designed, a testable hypothesis.

“Rainbow trout suffer more lice in low water conditions because there is less oxygen in the water.”

This is a testable hypothesis - he has established variables , and by measuring the amount of oxygen in the water, eliminating other controlled variables , such as temperature, he can see if there is a correlation against the number of lice on the fish.

This is an example of how a gradual focusing of research helps to define how to write a hypothesis .

- << Previous: Theory

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Oct 27, 2023 11:09 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mssu.edu/PSC340

This site is maintained by the librarians of George A. Spiva Library . If you have a question or comment about the Library's LibGuides, please contact the site administrator .

3 Social science theories, methods, and values

Learning Objectives for this Chapter

After reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

- understand, apply, and evaluate core social science values, concepts, and theories, which can help inform and guide our understanding of how the world works, how power is defined and exercised, and how we can critically understand and engage with these concepts when examining the world around us.

Social science theory: theories to explain the world around us

As we have discussed in previous chapters, social science research is concerned with discovering things about the social world: for instance, how people act in different situations, why people act the way they do, how their actions relate to broader social structures, and how societies function at both the micro and macro levels. However, without theory, the ‘social facts’ that we discover cannot be woven together into broader understandings about the world around us.

Theory is the ‘glue’ that holds social facts together. Theory helps us to conceptualise and explain why things are the way they are, rather than only focusing on how things are. In this sense, different theoretical perspectives, such as those discussed in this Chapter, act as different lenses through which we can see and interpret the world around us.

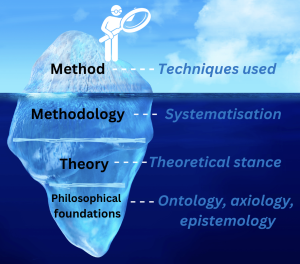

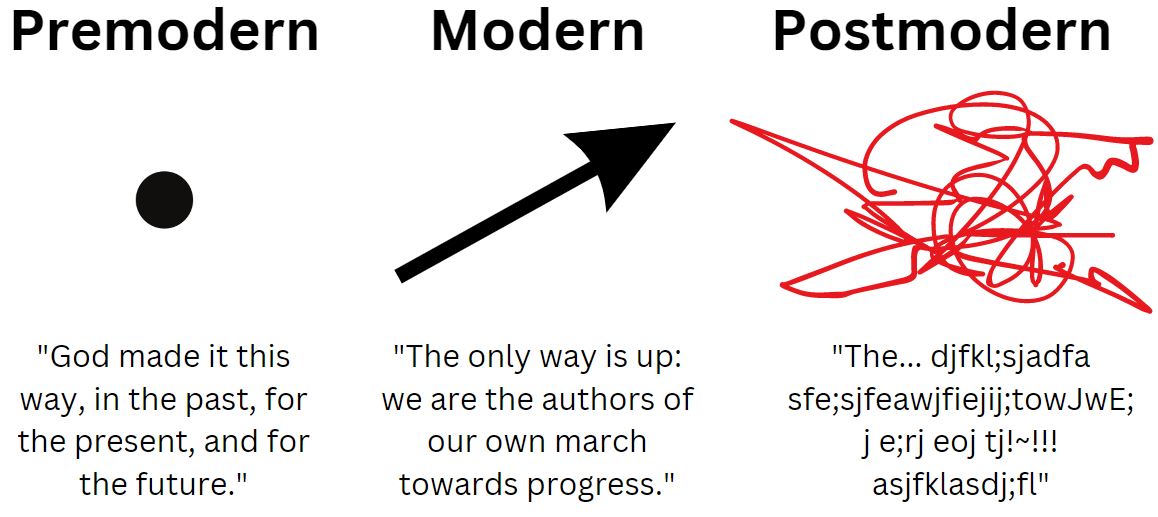

Theory testing and generation is also an important part of social scientific research. As shown in the image below, different theories are rooted in different philosophical foundations. That is, various theories arise in accordance with different ways of seeing and living in the world, as well as different understandings about how knowledge is understood and constructed. As we learned earlier in the book, these concern both ontological and epistemological considerations, but also axiological considerations; that is, questions about the nature of value, and what things in the world hold value (including in relation to one another). While theory is rooted in these philosophical foundations, however, it also gives way to different ways of doing research, both in terms of the methodology and methods employed. Overall, using different theoretical perspectives to consider social questions is a bit like putting on different pairs of glasses to see the world afresh.

Below we consider some foundational social science theories. While these are certainly not the only theoretical perspectives that exist, they are often considered to be amongst the most influential. They also provide helpful building blocks for understanding other theoretical perspectives, as well as how theory can be applied to guide and build social scientific knowledge.

Structural functionalism

Structural functionalism is a theory about social institutions, ‘social norms’ (i.e., the often unspoken rules that govern social behaviours), and social stability. We talk more about social institutions in the next Chapter of this book, but essentially they are the ‘big building blocks’ of society that act as both repositories and creators/instigators of social norms. These include things like school/education, the state (often called a meta-institution), the family, the economy, and more. In this regard, structural functionalism is considered a macro theory; that is, it considers macro (large) structures in society, and concerns how they work in an interdependent way to produce what structural functionalists believe to be ‘harmonious’ and stable societies. Structural functionalists are particularly concerned with social institutions’ manifest and latent functions, as well as their functions and dysfunctions (Merton [1910-2003]).

Manifest functions of social institutions include things that are overt and obvious. By contrast, latent functions of social institutions are those that are more hidden or secondary. For instance, a manifest function of the social institution of school is to teach students new knowledge and skills, which can assist them to move into chosen careers. Alternatively, we might also argue that school has other latent functions, such as socialisation and conformity to social norms, and building relationships with peers.

In addition to manifest and latent functions, structural functionalists are also concerned with the functions and dysfunctions of social institutions. They believe, for instance, that dysfunctions play just as much of an important role as functions, because they enable social institutions to identify and punish them, thereby making an example of dysfunctional elements (e.g., punishing those committing crime). This serves to reinforce social norms around how society should function.

Reflection exercise

Take a piece of paper and, in your own words, write down a brief definition of structural functionalism. Then re-read the above sub-section. How does your understanding fit with the information above?

Structural functionalism: want to learn more?

If you’d like to reinforce your understanding of structural functionalism, the below video provides a good summary that might be helpful.

Functionalism (YouTube, 5:40) :

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the study of our experiences and how our consciousness makes sense of the phenomena (be they objects, people or ideas) around us. As a methodology or approach in the social sciences it has garnered renewed interest in the last few decades to better understand the world around us by studying how we experience the world in a subjective and often individual manner. It is, thus, considered a ‘micro’ theory.

This philosophical approach was developed by Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), and his students and critics in France and Germany (key figures were philosophers Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961)) and later made it to the US via influential sociologists, such as Alfred Schütz (1899–1959).

Phenomenologists reject objectivity and instead focus on the subjective and intersubjective, the relations between people, and between people and objects. So, rather than trying to come to some objective truth, they are more interested in relationships and connections between the individual and the world around them. Indeed, there is a strong centering of and focus on the individual and their experiences of the world that phenomenologists believe can tell us about society at large. The individual is also key, as there is a focus on the sensory and the body both as instruments of enquiring as well as enquiry. Thus, we are always already part of the world around us and have to make sense of being here, but also want to go beyond ourselves by understanding others and how they relate to the world. The body features as a key site for such enquiries as it is the physical connection we have with people and objects around us. Further, there is a focus on everyday, mundane experiences as they have much to tell us about how society operates. This background environment in which we as people operate is called a lifeworld, the shared horizon of experience we share and inhabit. It is marked by linguistic, cultural, and social codes and norms.

One key method inherent to Husserl’s early approaches is ‘bracketing’ , the process of standing back or aside from phenomena to understand it better. Such processes of ‘reflexivity’ and understanding our taken for granted attitudes and beliefs about certain phenomena are crucial to enable the social sciences to better understand the world around us. Debates in philosophy continue around whether such a bracketing is ever fully possible, especially considering that we as humans remain trapped in our minds and bodies. Nonetheless, phenomenology has had a profound impact in most social sciences to redirect the focus towards the intersubjective nature of life and the lifeworld, within which we experience the world around us.

Take a piece of paper and, in your own words, write down a brief definition of phenomenology. Then re-read the above sub-section. How does your understanding fit with the information above?

Phenomenology: want to learn more?

If you’d like to reinforce your understanding of phenomenology, the below video provides a good summary that might be helpful.

Understanding Phenomenology (YouTube, 2:59) :

Symbolic interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is related to phenomenology as it is also a theory focused on the self. In this regard, it’s also a micro theory – it has particular focus on individuals and how they interact with one another. Symbolic interactionists say that symbolism is fundamental to how we see ourselves and how we see and interact with others. George Herbert Mead (1863-1931) is often regarded as the founder of this theory and his focus was on the relationship between the self and others in society. He considered our individual minds to function through interactions with others and through the shared meanings and symbols we create for the people and objects around us. Mead’s best known book Mind, Self, Society, was posthumously put together by his students and demonstrates how our individual minds allow us to use language and symbols to make sense of the world around us and how we construct a self based on how others perceive us.

Charles Cooley’s (1864-1929) concept of the “ looking glass self ” points out, for instance, that other peoples’ perceptions of us can also influence and change our perceptions of ourselves. Other sociologists, such as Erving Goffman (1922-1982), have built on this understanding, suggesting that ‘all of life is a stage’ and that each of us play different parts, like actors in a play. Goffman argued that we adapt our personality, behaviours, actions, and beliefs to suit the different contexts we find ourselves in. This understanding is often referred to as a ‘dramaturgical model’ of social interaction; it understands our social interactions to be performative – they are the outcomes of our ‘play acting’ different roles.

In explaining this theory, Goffman also referred to what he called ‘impression management’. As part of this, for instance, Goffman drew a crucial distinction between what he referred to as our ‘ front stage selves ‘ and our ‘ backstage selves ‘. For Goffman, our ‘front stage selves’ are those that we are willing to share with the ‘audience’ (e.g., the person or group with whom we are interacting). Alternatively, our ‘backstage selves’ are those that we keep for ourselves; this is the way we act when we are alone and have no audience.

Goffman also pointed to the important role that stigma can play in how we see ourselves and thus, how we act and behave in relation to others. Stigma occurs when “the reaction of others spoils normal identity”. Goffman argued that those who feel stigmatised by others (e.g., through public discourses and ‘frames’ of social issues that vilify certain groups of people) also experience changes in the way they see themselves – that is, their own sense of self-identity is ‘spoiled’. This can lead to other negative effects, such as social withdrawal and poorer health and wellbeing.

Take a piece of paper and, in your own words, write down a brief definition of symbolic interactionism. Then re-read the above sub-section. How does your understanding fit with the information above?

This exercise is to be conducted in small groups. First, get into a small group with other students. Then, do the following:

- Think about your daily life, activities, and interactions with others.

- Take a few moments to identify at least three examples of social symbols that you and other group members frequently use to interpret the world around you.

- Talk about how each of the group members interprets/responds to these symbols. Are there similarities? Are there differences?

Students should share/discuss their thoughts within the group, and if undertaken in a class environment, then report back to the class.

Symbolic interactionism: want to learn more?

If you’d like to reinforce your understanding of symbolic interactionism, the below videos provide good summaries that might be helpful.

Symbolic Interactionism (YouTube, 3:33) provides an easy-to-understand summary of symbolic interactionism:

What does it mean to be me? Erving Goffman and the Performed Self (YouTube, 1:58) provides a helpful summary of Erving Goffman’s conception of the ‘performed self’ – including his notions of a ‘front stage’ and ‘backstage’ self:

Conflict theories

Conflict theories focus particularly on conflict within and across societies and, thus, are particularly interested in power: where it does and doesn’t exist, who does and doesn’t hold it, and what they do or don’t do with it, for example. These theories hold that societies will always be characterised by states of conflict and competition over goods, resources, and more. These conflicts can arise along various lines, though

this group of theories emanate from the work of Karl Marx (1818-1883), who saw the capitalist economy as a primary site of conflict.

In Marx’s view, social ills emanated particularly from what he described as an upper- and lower-class structure, which had been perpetuated across multiple societies (e.g., in ancient societies in terms of slave owners/slaves, or in pre-Enlightenment times between the feudal peasantry/aristocracy). He saw capitalism as replicating this upper/lower class structure through the creation of a bourgeoisie (upper class, who own the means of production) and proletariat (lower class, who supply labour to the capitalist market). Marx also talked about a lumpenproletariat , an underclass without class consciousness and/or organised political power. Classical Marxism takes a macro lens: it is particularly concerned with how power is invested in the social institution of the capitalist economy. In this sense, classical Marxism represents a structural theory of power.

Marx argued that the only way for society to be fairer and more equal was if the proletariat was to rise up and revolt against the bourgeoisie; to “smash the chains of capitalism”! Thus, he strongly advocated for revolution as a means of creating a fairer, utopic society. He stated, “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it” (Marx 1968: 662). Nevertheless, a series of revolutions in the early 20th century that drew on Marxist thinking resulted in power vacuums that made way for violent, totalitarian regimes, as political philosopher Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) argued in On the Origins of Totalitarianism . On this basis, subsequent conflict theorists (and critical theorists) have tended towards advocating for more incremental reforms, as opposed to revolution.

Take a few moments to watch the below two videos, which explain conflict theory in greater detail.

Key concepts: Conflict theory – definition and critiques (YouTube, 2:49) :

Political theory – Karl Marx (YouTube, 9:27) :

After watching these videos, take a piece of paper and, in your own words, write down a definition of conflict theories. After doing so, re-read the above sub-section. How does your understanding fit with the information in the above sub-section, and in the videos? Was anything missing? Is anything still unclear?

Critical theories

Marx saw the capitalist economy as a primary site of oppression, between the working class and the property owning class. Marx advocated for revolution, where the proletariat were urged to rise up and break the chains of capitalism by overthrowing the bourgeoisie. Marx saw this as being necessary for ensuring the freedom of the working classes. Critical theory develops from the work of Karl Marx, supplementing his theory of capitalism with other sociological and philosophical concepts.

Gramsci and cultural hegemony

In addition to Marx, critical theory utilised the work of Italian political philosopher Antonio Gramsci, specifically his concept of ‘Cultural Hegemony’. When we refer to ‘hegemonic’ social norms, we’re referring to social norms that are regarded as ‘common sense’ and thus, which overshadow and suppress alternative norms. Hegemonic norms typically reflect the values of the ruling classes (in Marxist terms, the bourgeoisie). To learn more, you might like to watch the video below:

Hegemony: WTF? An introduction to Gramsci and cultural hegemony (YouTube, 6:25)

Developing from this, critical theory also considers how power and oppression can operate in more subtle ways across the whole of society. Critical theory does not seek to actively bring about revolution, as the possibility for a revolution in the years post-World War Two was unlikely. Whilst critical theorists are by no means opposed to revolution, their focus lies more in identifying how capitalist society and its institutions limits advancement of human civilisation. In this respect, conflict theorists see more opportunities for praxis than classical Marxists.

Critical theory observes how the Enlightenment ideals of freedom, reason, and liberalism have developed throughout the first half of the 1900s. Ultimately, critical theorists see that reason has not necessarily progressed in a positive way throughout history. In fact, reason has developed to become increasingly technical, interested in classifying, regulating, and standardising all aspects of human society and culture. German philosopher Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) thought that Nazi Germany and the holocaust is a devastating example of the potential evils of rationality if developed without a critical perspective.

Another, less extreme, example of this tendency toward standardisation is in the production of art and culture. Big budget films, typically in the superhero or science fiction genre, all appear to be virtually identical: extravagant special effects, epic soundtracks, and relatively simple plots. However, this is not to say that such films are of a poor quality. Rather the similarity and popularity of these films indicates a homogenisation of culture. If culture is merely the reproduction of the same, how can society progress beyond its current point?

This critique of the development of reason throughout the 20th century does not mean that we must abandon reason entirely. To do so would be to discount the vast wealth of knowledge that humanity has come to grasp, as well as prevent further knowledge production. Instead, critical theorists argue that reason should be critiqued to uncover what has been left out of its development thus far, as well as open up the possibility for a more free, progressive form of society.

At its core, then, critical theory can be thought about as being an additional theoretical lens through which we can look at and understand the social world around us. In tune with Flyvbjerg’s (2001) conception of phronetic social science, critical theorists are also concerned with disrupting the systems they observe as a means of achieving social change. Critical theory urges us to recognise, understand and address how capitalist society reproduces itself and limits the free organisation of human beings.

Take a few moments to watch Critical theory definition and critiques (YouTube, 3:26) , which explains critical theory in greater detail.

Take a piece of paper and, in your own words, write down a brief definition of critical theories. Then re-read the above sub-section. How does your understanding fit with the information above and the video?

Critical theory can be applied in myriad different ways to better understand the world around us. In Critical theory and the production of mass culture (YouTube, 2:12) , critical theory is adopted as a lens to understand and critique the production of mass culture. Watch the video and then consider the questions below.

- Can you think of examples where you could argue that the primary objective of producing art is to preserve the economic structure of the capitalist system?

- Do you agree with the proposition that mass-consumed entertainment, like popular television shows, are only produced as a source of light entertainment and escapism from work, and thus serve to placate and pacify the worker? Why or why not? (What other purposes might such entertainment serve, if any?)

- Do you agree with Adorno’s proposition that the products of the ‘culture industry’ are not only the artworks, but also the consumers themselves? Why or why not?

Critical race theory

Critical race theory applies a critical theory lens to the notion of race, seeking to understand how the concept of race itself can act as a site of power and oppression. Arising from the work of American legal scholars during the 1980s (including key thinkers like Derrick Bell [1930-2011] and Kimberlé Crenshaw [1959-]), it originally sought to understand and challenge “the ways in which race and racial power [were]… cosnstructed and represented in American legal culture and, more generally, in American society as a whole.” (Crenshaw et al. 1995: xiii) In particular, it questioned whether the civil rights afforded to African Americans in the aftermath of the civil rights movement had made a substantive impact on their experiences of social justice. Critical race theorists argued that more needed to be done; that civil rights had not had the desired impacts because (amongst other reasons) they:

- were imagined, shaped and brought into being by (predominantly) white, male middle- or upper-class lawyers, and thus, were only imagined within the bounds of white ontology,

- did not move beyond race – race still mattered, and

- implicitly perpetuated white privilege (e.g. they were constrained to only imagine redress and justice within the existing oppressive, white hegmonic system).

Crenshaw (1995: xiii) writes that, although critical race scholars’ work is heterogenous, they are nevertheless united by the following common interests:

- “The first is to understand how a regime of white supremacy and its subordination of people of color have been created and maintained in America, and, in particular, to examine the relationship between that social structure and professed ideas such as ‘the rule of law’ and ‘equal protection’.”

- “The second is a desire not merely to understand the vexed bond between law and racial power but to change it.”

In Australia, scholars have also taken up aspects of a critical race lens to understand how privilege is bound up with race. As Moreton-Robinson (2015: xiii) puts it, in Australia:

Race matters in the lives of all peoples; for some people it confers unearned privileges, and for others it is the mark of inferiority. Daily newspapers, radio, television, and social media usually portray Indigenous peoples as a deficit model of humanity. We are overrepresented as always lacking, dysfunctional, alcoholic, violent, needy, and lazy… For Indigenous people, white possession is not unmarked, unnamed or invisible; it is hypervisible…

Crenshaw has been crucial in also stressing the key importance of understanding how race can also intersect with other aspects of social identity, such as gender, to produce a ‘double’ or ‘triple’ oppression. In Australia, Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson’s 2000 book, Talkin’ up to the white woman, was also crucial in understanding how Australian feminism could also be oppressive of Indigenous Australian women by not seeing and hearing them or the specific issues they face/d. She called for the need for “white feminists to relinquish some power, dominance and privilege in Australian feminism to give Indigenous women’s interest some priority” (Moreton-Robinson 2000: xxv). This emphasised that an intersectional lens was needed to acknowledge the different but cumulative impacts of both racial oppression and sexism. At the centre of this argument is the reality that “all white feminists [in Australia] benefit from colonisation; they are overwhelmingly represented and disproportionately predominant, have the key roles, and constitute the norm, the ordinary and the standard of womanhood in Australia” (Moreton-Robinson 2000: xxv).

Uproar over critical race theory

During 2020, racial sensitivity training in the USA prompted widespread discussion about critical race theory. Former US President, Donald Trump, posits in the video below that the theory, and the kinds of racial sensitivity training it promotes, are fundamentally racist – against white people. Others argued that this represented a deep misunderstanding of the theory, but also an ignorance of the extent and power of white privilege.

For an example of former President Trump’s views, watch Trump: Racial sensitivity training on white privilege is ‘racist’ (YouTube, 3:16) :

Postmodern critique of critical race theory

Postmodernists have levelled critique at critical race theory on the basis that understanding/explaining power as being rooted in racial difference has the consequence of reinforcing and perpetuating the validity of ‘race’. Postmodernism, however, rejects the distinct, conceptual bounds of ‘race’ and racialised identities. Instead, it sees race itself as a social construction, which should be questioned and disrupted, thereby leading to new insights that aren’t constrained by socially constructed definitions of race.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, for example, seeks to “probe the very definitions of race itself. He bypasses the empirical question of whether racism exists to ask the theoretical question of what race and racism are” (in Chong-Soon Lee 1995: 441)

Take a piece of paper and, in your own words, write down a brief definition of critical race theory . Then re-read the above sub-section. How does your understanding fit with the information above?

Putting theory into action: rethinking crime through a critical lens

Critical criminologists apply a critical theory lens to the study of crime and criminality. In this regard, critical criminology is concerned with understanding how the criminal justice system can act as a site of power and oppression; a perspective that tends to sit in contrast with western (non-critical) criminology, which sees the criminal justice system as a natural social institution that has the primarily purpose of protecting society against deviants (criminals) and making an example of those who fail to comply with hegemonic social norms. (This non-critical view draws parallels, for example, with the perceived ‘functions’ of the criminal justice system under a structural functionalist perspective, and its role in making examples of ‘dysfunctional’ elements of society.)

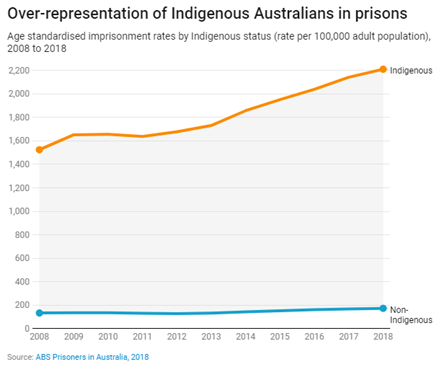

Critical criminologists in Australia have considered the role of the criminal justice system as a key site of oppression under, for example, Australian settler colonialism. For instance, Indigenous Australians are, per capita, the most incarcerated peoples in the entire world ( Anthony & Baldry 2017 ) and these incarceration rates are rising, not reducing (ABS 2018). In using a critical lens to understand the difference between incarceration rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, however, we can seek better insight into how the criminal justice system operates as a site of oppression, perpetuating white settler colonial norms and values, which seek to punish alternative ontologies and epistemologies. Lynch (cited in Cunneen and Tauri 2016: 26) argued,

In short, criminology is one of the disciplines that established the conditions necessary for maintenance of the status quo of power. It can only do so by oppressing those who would undermine the status quo. In this sense, criminology must be viewed as a science of oppression.

In part, this oppression operates through the construction of knowledge and truth within (positivist) criminology (which relates to Foucault’s conception of power-knowledge, as we touched on last week). In turn, this also involves what Cunneen and Tauri (2016: 26) describe as “the ideologically driven dismissal of Indigenous knowledge about the social world as ‘subjective’, ‘unscientific’, and/or at best ‘folk epistemology’… which in turn paves the way for excluding other ways of knowing from the Western, criminological lexicon”.

In their book, Decolonising criminology, Blagg and Anthony (2019: 22-23) set out a taxonomy for what they see as a decolonised criminology (noting, though, that Blagg and Anthony themselves are non-Indigenous researchers, though they have worked closely with Indigenous peoples and communities for decades). In their taxonomy (which we have included an adapted version of below), they include the following probing comparisons between a positivist (largely uncritical) criminology and a decolonised (critical) criminology:

A table comparing positivist and decolonial approaches to criminology.

Source: Authors’ adaptation from Blagg & Anthony (2019: 22-23 )

The probes and questions that Blagg & Anthony pose in the above taxonomy are critical in their focus and intent; they seek to critique the criminal justice system as a site of colonial power, but they also seek to change it — through research that produces knowledge about these truths. This is, in essence, a reframing (to use Bacchi’s term) of the nature of criminological research towards a richer, and more historically and culturally contextualised understanding of the Australian criminal justice system. As a result, this produces different knowledge about crime and justice in Australia: knowledge that shifts blame away from the individual (the ‘bad’ Indigenous citizen, to use Moreton-Robinson’s [2009] language) to the structures, history and continuation of colonial oppression.

Critical or radical criminology?

Radical criminology is rooted in the Marxist conflict tradition and sees the capitalist economy as being central to the definitions of crime (arrived at by the bourgeoisie) that constrict, control and suppress the working classes (proletariat).

In contrast (or in addition to), critical criminology is interested in more than just class relations and also sees different opportunities for praxis – tending to favour a more incremental approach to social change as opposed to widespread revolution ( Bernard 1981 )

Drawing on a critical criminology and decolonising perspective, consider the below graph, which shows the over-representation of Indigenous Australians in prisons, indicating an upward trend from 2008-2018. Then consider, from a critical criminology standpoint, what kinds of ‘truths’ might you draw on to help explain this trend?

(To guide your thinking, you may like to revisit the above taxonomy by Blagg and Anthony.)

Watch the below short clip of Senator Patrick Dodson talking in March 2021 about the issue of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in custody. Consider LNP Senator, Amanda Stoker’s response to Senator Pat Dodson, in particular her comment that she “understand[s] the outrage is real… because the lives of every person, though our justice system are important, no matter the colour of their skin.”

In #Estimates , @SenatorDodson fires up over a lack of action on deaths in custody. @stoker_aj ‘s response: “I understand the outrage is real…because the lives of every person, through our justice system are important, no matter the colour of their skin.” #Auspol @SBSNews @NITV pic.twitter.com/jgsb8y9YcD — Naveen Razik (@naveenjrazik) March 26, 2021

What do you think about Senator Stoker’s response to Senator Dodson? How might you analyse her response, through a critical race theory lens?

Choose one of the following social issues:

- The gender pay gap

- The workplace ‘stress’ epidemic

- Homelessness

- Childhood obesity

Consider how your chosen social issue might be explained by drawing on the different theoretical perspectives outlined earlier in this Chapter. Record your thoughts in a short, written explanation.

Reflection exercise: a critical reading of meritocracy

Kim and Choi (2017: 112) define meritocracy as “a social system in which advancement in society is based on an individual’s capabilities and merits rather than on the basis of family, wealth, or social background.” According to Kim and Choi (2017: 116), meritocracy has two key features: “impartial competition” and “equality of opportunity”.

The notion of meritocracy has arisen over the past few centuries primarily in response to feudalism and absolute monarchy, where power and privilege are handed down on the basis of familial lines (‘nepotism’) or friendships (‘cronyism’). This kind of system could (and often did) place people into positions of power, regardless of whether they were the most appropriate or ‘best’ person for the job. In essence, then, the notion of meritocracy is intended to tie social advancement to merit; that is, the focus is supposed to be on ‘what you know’ rather than ‘who you know’, which seems a noble cause, right? Many have argued, however, that a blinkered belief in meritocracy leaves a lot of things out of the ‘frame’.

The belief in meritocracy, and its focus on ‘what you know’ rather than ‘who you know’, can have both positive and negative impacts. Take a piece of paper and write a short list of each.

If critical theory operates according to the broad Marxist understanding of history as class struggle, post-structuralism is a theory that attempts to abandon the idea of grand historical narratives altogether. Fundamentally, post-structuralism differs from other social theories in its rejection of metanarratives , its critique of binaries, and its refusal to understand all human action as being shaped solely by universal social structures. Whilst there is much disagreement between post-structuralist thinkers, these three broad trends help us to understand this social theory.

Post-structuralism