Columbia University Libraries

Hausa language and culture acquisitions at columbia: biography, culture, history, proverbs, religion, and society.

- Grammars, Phrasebooks, and Textbooks

- Linguistics

- Drama, Folktales, Novellas, Novels, Poetry, Readers, and Short Stories

- Biography, Culture, History, Proverbs, Religion, and Society

- Related Works in Arabic, English, French, and German

Biography, Culture, History, Proverbs, Religion, & Society

- Abba, Abdullahi. Tarihin Bauchi ta Yakubu . Zaria [Nigeria] : Gaskiya Corp., 1993. (71 p.) [In Hausa, a history of the Bauchi kings since the 19th century.]

- ʻAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad. Jagorar shugabanci a musulunci da warwarar wasu matsaloli na addini : talifin Shehu Abdullahi Dan Fodiyo . Kano [Nigeria] : Cibiyar Nazarin Harsunan Nijeriya, [1992]. (138 p.) [Early 19th century Hausa work on Islamic leadership by emir of Gwandu, brother of Uthman dan Fodio, founder of the Sokoto Caliphate.]

- ʻAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad. Littafin kitabun-niyyati fil a'malid-dunyawiyyati wad-di'niyyati . [Edited and comments by] Muhammad Isa Talata-Mafara. [Nigeria : s.n.], [1992] (60 p.) [Selected writings of early 19th century emir of Gwandu, brother of Uthman dan Fodio, founder of the Sokoto Caliphate.]

- ʻAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad, Emir of Gwandu, c1767-1829. Zaɓaɓɓun littattaffai na Shehu Abdullahi Ɗan Fodiyo . 3 vols. Samaru, Gusau : Iqra'ah Publishing House, [2013] --See also: English translation

- Abdulkadir, Dandatti. The poetry, life, and opinions of Saʾadu Zungur . Zaria : Northern Nigerian Pub. Co., 1974. (109 p.) [English & Hausa] --See also: Zungur, Sa'adu below.

- Abdullahi, Shehu Umar. Gaskiya dokin k̳arfe . Kano, Nigeria : Mai-Nasara Printing, 1985. (127 p.) [In Hausa, essays on Hausa culture, Islam, social change, politics, & development in Nigeria under colonialism and in the post-colonial era.]

- Abubakar, Alhaji. Kano ta dabo cigari . Zaria: Northern Nigerian Publishing Co., 1978. (105 p.) [In Hausa, a history of Kano.]

- Abubakar Gidado El-Nafaty. Tarihin Islam . Zaria: Northern Nigerian Publishing Company, 1977 (1979 printing). (259 p.) [In Hausa, a history of Islam.]

- Abubakar, Mohammed N. and Alhasan Sule. Tarihin rayuwar Dr. Alhaji Mamman Shata . [Kano : s.n., 1998?] (78 p.) [Biography.]

- Abubuwan da za a yi a taki na karshe : abin da ya kamata ka sani. [Nigeria] : National Electoral Commission, [1992 or 1993] (20 p.) [A voter and election monitoring guide.]

- Adewuya, Anthonia V., Malam Abubakar, Ahmadu Yaro, and Garba Umar Suru. Hanyar zaman iyali : tattalin gida domin yara maza da mata a makarantun Firamaren Nijeriya : littafi na uku . Ibadan, Nigeria : Onibonoje Press, 1988. (31 p.) [In Hausa, on nutrition, cleanliness, & preventive health.]

- Ahmed, Abubakar Sadiq. Tarihin rayuwar Alhaji Nababa Badamasi . Nigeria: Uniprinters Limited, [199-?] (68 p.) [Biography]

- Anwar, Auwalu. Tasirin siyasa a addini : tijjanawa da tirjanawa a Kano, 1937-1991 . [Zaria, Nigeria] : Stronglink, c1992. (61 p.) [In Hausa, on the political history of Tijani Muslims in 20th century Kano.]

- Asma'u, Nana. Collected works of Nana Asma'u, daughter of Usman dan Fodiyo, (1793-1864). [Edited by Jean Boyd and Beverly B. Mack.] African historical sources; no. 9 . East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, [1997] (753 p.) [English analysis, with Hausa texts & English translations.] --See also: E-book [Columbia only!]

- Baagil, Hasan M. Muslim-Christian dialogue = Muhawara tsakanin Musulmi da Krista [na Muhammad Bin Uthman.] Kano : [s.n.], 1999. (112 p.) [Mostly in Hausa.]

- Baba, of Karo. Labarin Baba: mutuniyar Karo ta kasar Kano . Transcribed and translated by Mary Smith ta rubuta; ta tsara da taimakon Neil Skinner. Madison, Wis.: African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, c1993. (89 p.; originally published in English in 1954) [An autobiographical account in Hausa, with sociological insights.] --See also: 1981 English ed. ; Law Library copy of 1981 ed. --Plus: 1964 English ed . --Plus: 1955 English ed. --And: 1954 English ed. ; Burke Library copy of 1954 ed.

- Bahago, Ahmad. Kano ta dabo tumbin giwa: tarihin unguwannin Kano da mazaunanta da ganuwa da kofofin Gari . Kano: Munawwar Books Foundation, 1998. (237 p.) [In Hausa, a history of Kano.]

- Bahaushiya : bukin makon Hausa na farko na Kungiyar Habaka Hausa, Jamiʾar Ahmadu Bello ta Zariya . [Zaria, Nigeria : Ahmadu Bello University, 1986?] (223 p.) [In Hausa, selected proceedings from a conference held at Ahmadu Bello University in March 1985 on Hausa language, literature & culture, including several poetic texts.]

- Bello, Muḥammad, Sultan of Sokoto, 1781-1837. Zaɓaɓɓun littattaffai na Sarkin Musulmi Muhammadu Bello . 2 vols. Samaru, Gusau : Iqra'ah Publishing House, [2013] --See also: English translation

- Bello, Omar. Jaddada addini a kasar Hausa : jihadin Shaykh Uthman b. Foduye . [Sokoto] : Islamic Academy, [1994] (23 p.) [In Hausa, on the jihad of Uthman dan Fodio, founder of the Sokoto Caliphate.]

- Burji, Badamasi Shu'aibu G. Gaskiya nagartar namiji : tarihin rayuwar Janar Hassan Usman Katsina Kano : Burji Publishers, 1997. (462 p.) [Biography{

- Dahiru, Muhammad Sanusi. Laifin wa? . Katsina : Na-Hamisu Press, 1996. (54 p.) [On Hausa culture.]

- Dalhat, M. T. Ilimin jima'i a musulunci . Kaduna : Alkausar Print. and Pub. Co., 1993. (73 p.) [In Hausa, about sexual relations in Islam.]

- Daure, Buhari. Tarihi da al'adun mutanen Najeriya . [Katsina? : s.n., 1998?] (90 p.) [Nigerian history]

- Dodo, Aishatu Nurudeen. Taran aradu da ka . Kaduna : Bamoya Printing Press, 1997. (35 p.) [In Hausa, on marriage.]

- Durumin-Iya, Salisu Mai'Unguwa. Kissar Sarauniya Bilkisu : mai gadon zinare . Kano : [s.n.], 1998. (31 p.) [A pamphlet in Hausa, commentary on Islam.]

- East, Rupert Moultrie and Alhaji Abubakar Imam. Ikon Allah: labarin halita iri iri ta cikin duniya . 5 vols. Zaria: Northern Nigerian Pub. Co., c1966 (1977 printing). [Natural history]

- Fletcher, Roland S. Hausa sayings & folk-lore; with a vocabulary of new words . London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1912. (173 p.)

- Gamagira, Sa'idu. Littafin mafarki . Zaria : Northern Nigerian Pub. Co., c1970- [In Hausa, about dreams; Columbia only has volume 1.]

- Guibe, Is'haq Idris. Rayayyen nahawun larabci da ka'Idojinsa = al-Naḥw al-wā ḍiḥ fī qawā ʻid al-lughah al-ʻArabī yah . Kaduna: Kauran Wali Islamic Bookshop, 1998. [In Hausa, on the Arabic language ; Columbia has only volume 1.]

- Gusau, Sa'idu Muhammad. Dabarun nazarin adabin hausa . Kaduna : Dab'in Fisbas Media Services, 1995. (72 p.) [On Hausa writers, works by colonial European writers on Hausa language & culture, & modern researchers (African & nonAfrican) & their contributions.]

- Gusau, Sa'idu Muhammad. Jagorar nazarin wakar baka . Kaduna : Dab'in Fisbas Media Services, 1993. (81 p.) [A study of Hausa spoken language.]

- Gusau, Sa'idu Muhammad. Madad̳a da mawakan Hausa . Kaduna : Fisbas Media Services, [1996] [Biographical sketches of Hausa rulers in the 20th century.]

- Hakīm, Tawfīq. Mutanen kogo . Mai fassara Ahmed Sabir. Ibadan, Nigeria: Oxford University Press, c1976. (105 p.) [A dramatization in Hausa, based on the 18th sura in the Noble Quran, "The Cave".]

- Hiskett, Mervyn. A history of Hausa Islamic verse . London : University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1975. (274 p.)

- Histoire du Dawra . [Traditions historiques du Dawra par Makada Ibira de Kantché ; transcription et traduction par Issaka Dankousso.] Niamey, Niger: Centre régional de documentation pour la tradition orale, 1970. (39 leaves.) [Hausa & French]

- Imam, Tijani M. Hikayoyin Shehu Jaha . 2 vols. Kano : Baitul Hikmah, 1998. [Stories in Hausa about 13th century Seljuq Sufi philosopher in what is now Turkey, known for his satire.]

- Jaggar, Philip J. Hausa newspaper reader . Kensington, Md.: Dunwoody, c1996. (225 p.)

- Jahun, Lauya Suleiman Ibrahim. Sarkin kano : alu maisango . Kano : Alaramma Books Centre, c1986. (94 p.) [In Hausa, on the emir of Kano.]

- Kano, Aminu. Rayuwar Ahmad Mahmud Sa'adu Zungur . Zaria: Northern Nigerian Pub. Co., 1973. (17 p.) [A short biography of Sa'sadu Zungur, Nigerian nationalist.]

- Ka'oje, Abdullahi. Dare Daya : Allah kan yi Bature . Zaria : Northern Nigerian Publishing Company, 1973, reprint c1978. (71 p.)

- Kirk-Greene, Anthony Hamilton Millard. (trans.) Hausa ba dabo ba ne; a collection of 500 proverbs . Translated and annotated by A. H. M. Kirk-Greene. Ibadan [Nigeria] Oxford University Press, 1966. (84 p.) [English & Hausa]

- Kubau, Y.A. Shi, hijabi umarnin wane ne? . Kano : Garba Mohammed Bookshop, 1996. (20 p.) [A pamphlet on the religious & social meaning of the hijab.]

- Kure, Mai Kudi. Shaida bishara ga Musulmi Hausawa da Fulani musamman : da yadda za a goyi Musulmi wanda ya tuba . [S.l. : s.n., c1990] (Jos [Nigeria] : Covenant Press) (35 p.) [In Hausa, about Christian converts among Muslim Hausa.]

- Kwalli, Kabiru Mohammed. Kano Jalla babbar Hausa . [Kano? : s.n.], 1996. (313 p.) [In Hausa, a history of Kano.]

- Labarun Hausawa da makwabtansu . 2 vols. Zaria: Northern Nigerian Pub. Co., 1970 (1979 printing). [In Hausa, on the political history of the Hausa and their neighbors.]

- Littafin wakoki. Jos, Nigeria : Published for Christian Media Fellowship by Challenge Publications, 1982. (365 p.) [In Hausa translation, a book of Christian hymns.]

- Maigari, Muhammad Tahir. Ilimin alkalanci na shari'a . Kano, Nigeria : Fairamma Publishing Co., 1991. [In Hausa, on Islamic law.]

- Makarfi, Abdulkarim A. Garba. Sarkin Zazzau : Malam Ja'afaru 'Dan Is'hak . Zaria : Makarfi Publishing, 1990. (138 p.) [In Hausa, a profile of Ja'afaru 'Dan Is'hak, emir of Zazzau or Zaria.]

- Malumfashi, Ibrahim. Asalin zuriyar galaduncin Katsina . [Kaduna: NNN, Commercial Printing Dept., 1990] (48 p.) [In Hausa, on the galadimas, rulers of Katsina.]

- Merrick, George. Hausa proverbs . New York, Negro Universities Press [1969] (113 p.) [English & Hausa] --See also: 1905 ed.

- Muhammad, Mahmoud Aliyu. Hanyoyin tsari daga kamuwa da cutar al-jannu da sihiri da rashin lafiya mai wuyar magani . Kano : Burji Publishers, [1998?] (20 p.)

- Nafiou, Rabiou. La sagesse populaire haoussa en 300 proverbes et dictons : ou Kogin Hikima . Paris : L'Harmattan, [2014] (81 p.) [French & Hausa}

- Nawawī. Hadisai Arbaʾin : = al-Arbaʻūn ḥadithan al-Nawawīyah . [Translated by] Alhaji Abubakar Mahmud Gumi. Zaria : The Northern Nigerian Publishing Co., 1982. (24 p.) [In Hausa translation, selected hadiths of 13th century Shafi'ite Imam Nawawi.]

- Nuruddeen, Ibrahim. Fate-fate kan tona . Kano : Munawwar Books Foundation, 1997. (59 p.) [In Hausa, a memoir of Yusuf Halilu's experiences in 20th century London, England.]

- Omoruyi, Omo. Taimakon Mallam Aminu Kano dangane da fahimtar da talaka siyasa a Nijeriya . Abuja : Cibiyar Nazarin Dimokaradiyya, 1992. (35 p.) [In Hausa, about Aminu Kano and his leadership role in the politics of the poor in Nigeria.]

- Othman, Mairo Yusuf. Rikon gida sai mata . Kano : Masbel Press, [199-?]- [On home economics & crafts; Columbia only has volume 1.]

- Pilaszewicz, Stanislaw. The Zabarma conquest of north-west Ghana and upper Volta: a Hausa narrative "Histories of Samory and Babatu and others" by Mallam Abu . Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers, 1992. (207 p.) [English commentary, with Hausa historical texts in Arabic script & transliteration.]

- Prietze, Rudolf. Haussa-sprichwörter und Haussa-lieder . Kirchhain N.-L., Buchdruckerei von M. Schmersow, 1904. (85 p.) [In German & Hausa, collected & edited Hausa proverbs & songs.]

- Rattray, Robert Sutherland (ed. & trans.) Hausa folk-lore, customs, proverbs, etc . 2 vols. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1969. [Hausa texts, in Arabic script (or àjàmi), with Roman transliteration & English translation.] --See also: 1913 ed. ; Burke Library copy --Plus: E-book [Columbia only!]

- Rayuwar Hausawa . [Compiled by] Cibiyar Nazarin Harsunan Nijeriya, Jamiʾar Bayero = Bayero University. Centre for the Study of Nigerian Languages. Lagos : Thomas Nelson (Nigeria) Ltd., 1981. (46 p.) [On Hausa history & culture.]

- Ringim, Alhaji Ibrahim Bello. Salsalar ya'yan Abdullahi Maje Karofi da Jikokinsa . Kano : [s.n.], 1997. (66 p.) [In Hausa, a history of the Karofi family.]

- Ringim, Maryam Uba. Me ke kawo mutuwar aure? Kano : Jihisa Secretaries, 1998. (74 p.)

- Sani, Umar Mohammed. Tsabta da kare kai daga cuta . Zaria : Huda Huda Pub. Co., 1997- [In Hausa, a pamphlet on nutrition, cleanliness, & preventive health; Columbia only has volume 1.]

- Schön, James Frederick. Magana Hausa : native literature, or proverbs, tales, fables and historical fragments in the Hausa language . [To which is added a translation in English.] 2 vols. Nendeln: Kraus Reprint, [1885-1886], reprint 1970. [In Hausa & English, a collection of proverbs, folktales, & life & travels of "Dorugu" accompanying Heinrich Barth in Africa, England, & Germany,] --See also: E-book [Columbia onlyl!]

- Sharīf, Muḥammad Shākir. Illolin raba siyasa da addini : da hadarin kafirar gwamnati . [Edited by] Abdullahi Jibril Ahmed. [S.l.] : Atta'awun Pub., [1991?]. (25 p.) [In Hausa, on Islam & politics.]

- Soron Dinki, Dahiru Umar. Ulama'u na Allah : tarihin Imam Abu Hanifa da kuma Imam Malik (R.A.) . Kano : Dahiru Umar Sorondinki, [1998?]- [In Hausa, a multi-volume work on Islam & biography of Abu Hanifa; Columbia only has volume 1.]

- Sufi, Husaini Ahmad. Wali Sulaimanu a tarihin Kano . Kano : Mali-Nasara Press, [1993?]. (415 p.) [On the history of Kano, with biographical sketches of rulers & prominent persons.]

- Suleiman, Amina Garba. Ciki da goyo ikon Allah . Kano: A-Z Printers, 1999- [In Hausa, a handbook for expectant & new mothers on nutrition, pre-natal, & post-natal care; Columbia library only has volume 1.]

- Talata-Mafara, Muhammad Isa. Daular usmaniyya : rayuwar sheshu usman danfodiyo da gwagwarmayarsa : littafi na farko . Zaria : Hudahuda, 1419 [1999] (156 p.) [In Hausa, a biography of Usman dan Fodio, & on the political history of major cities & emirates in the Sokoto caliphate.]

- Tarihi, Hukumar Binciken. Garuruwan Jihar Katsina . Na Hukumar Binciken Tarihi da Kyautata Al'adu ta jihar Katsina. 2 vols. [Katsina : s.n.], 1996- [In Hausa, on the kings & rulers of Katsina.]

- Tarihin Sheikh Ibrahim Inyas (R.T.A.) : takaitaccan tarihin sheihul Islam, Assaiyidi Ibrahim Inyas Khaulaha Attijjaniyu (R.T.A.) wanda aka rairayo shi a cikin (Hayatus Sheikh) . [Kano? : s.n., 1998?] (35 p.) [A biography of Sheikh Ibrahim Niass of the Tijani sufi order.]

- Tattalin albarkatun kasa : tarin takardun da aka gabatar a taron aikin gayya na farko kan tattalin albarkatun kasa wanda reshen jihar kano na kungiyar tattalin albarkatun kasa, ya gudanar . Tsantsamewa da tsarawar Abba Rufa'i. Kano, Nigeria : Bayero University, 1991. (93 p.) [In Hausa, on land use & environment in northern Nigeria.]

- Tijjani, Safiya A. Aure dodon maza-- . [Kaduna? : s.n.], 1997. (46 p.) [In Hausa, a pamphlet on money & gender relations.]

- Tremearne, Arthur John Newman. The Niger and the West Sudan; or, The West African's note book . A vade mecum containing hints and suggestions as to what is required by Britons in West Africa, together with historical and anthropological notes and easy Hausa phrases used in everyday conversation. London, Hodder & Stoughton [etc., pref. 1910] (151 p.)

- Umaru, Alhaji. Hausa prose writings in Ajami by Alhaji Umaru ; from A. Mischlich . H. Sölken's collection ; Stanislaw Pilaszewicz. Sprache und Oralität in Afrika; 22. Bd . Berlin: Reimer, 2000. (507 p.) [Selections from 11 Hausa manuscripts written in the àjàmi script.]

- Usuman dan Fodio, 1754-1817. Waṣīyat al-Shaykh ʻUthmān ibn Fūdī . al-nāshir, Manjū Muṣṭafá Jūkūlū ibn Amīr Ghawand al-Ḥājj Hārūn al-Rashīd. Zāriyā, Nījīriyā : Maṭbaʻat Ghasikiyā Kūfarīshin, [1989?] (48, 36 p.) [In Arabic & Hausa, the will & testament of the founder of the Sokoto Caliphate.]

- Usuman dan Fodio, 1754-1817. Zaɓaɓɓun littattaffai na Shehu Usumanu Ɗan Fodiyo . 3 vols. Samaru, Gusau : Iqra'ah Publishing House, [2013] --See also: English translation

- Wali, Naʼibi Sulaimanu. Duniya ina za ki da mu? [Zaria : Northern Nigeria Pub. Co.], 1974 (1979 printing) (60 p.) [On Hausa culture & morals.]

- Westley, David. Hausa oral traditions: an annotated bibliography . Working papers in African studies ; no. 15. Boston, MA: African Studies Center, Boston University, c1991. (22 leaves)

- Yahaya, Ibrahim Yaro. Hausa a rubuce : tarihin rubuce rubuce cikin Hausa . Zaria : Kamfanin Buga Littattafai Na Nigeria Ta Arewa, 1988. (344 p.) [A history of Hausa written literature.]

- Yakasai, Kabiru Ibrahim. Kasuwa a kai miki dole : tarihin kasuwanni da ciniki a kasar Kano . [Nigeria] : K.I. Yakasai, 1994. (205 p.) [In Hausa, on the markets of Kano.]

- Yunusa, Yusufu. Hausa a dunkule . Illustrations by Tsalhatu Amfani Joe. Zaria : Northern Nigerian Publishing Co., 1978. (120 p.) [Hausa proverbs.]

- Ziyara, Nasiru Musa. Khalifa : Khalifa Shekh Ishaq Rabiu . Kano : Hakima Graphic, 1995. (220 p.) [Biography of Shekh Ishaq Rabiu of Kano.]

- Zungur, Saʼadu. Saʾadu Zungur : an anthology of the social and political writings of a Nigerian nationalist . Edited by Alhaji Mahmood Yakubu. Kaduna, Nigeria : Nigerian Defence Academy Press, 1999. (453 p.) [English & Hausa}

- << Previous: Drama, Folktales, Novellas, Novels, Poetry, Readers, and Short Stories

- Next: Related Works in Arabic, English, French, and German >>

- Last Updated: Dec 20, 2023 11:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.columbia.edu/hausa-language

- Donate Books or Items

- Suggestions & Feedback

- Report an E-Resource Problem

- The Bancroft Prizes

- Student Library Advisory Committee

- Jobs & Internships

- Behind the Scenes at Columbia's Libraries

- News in English

- News in German

- Press Releases in German

- Imprint/Contact

- Institutions

- Prospective Students

- Ph.D. Candidates

- Researchers

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin - Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - Department of African Studies

The hausa language.

Hausa is classified as a member of the Chadic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family of languages. It is the best known and most important member of the Chadic branch. It is the most widely used in the fields of education and it lays claim to a significant literatures. By way of number, it is spoken by an estimated 40 to 50 million people as a first and second language thus, it believed to be one of the most commonly spoken African languages.

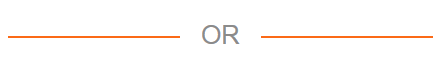

Where is Hausa Spoken?

Most Hausa speakers live in Northern Nigeria and Southern Republic of Niger. In Nigeria, Hausa-speaking area encompasses the historical emirates of Kano, Katsina, Daura, Zaria and Gobir, all of which were incorporated into the Sokoto caliphate following the Fulani Jihad led by Usman Shehu Ɗanfodio in the early 19 th century. Hausa is also spoken in diaspora by traders, scholars and immigrants in urban areas of West Africa, for example, southern and central Nigeria, Benin Republic, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Togo as well as Chad and the Blue Nile Province and western region of the Sudan.

Hausa and its Dialects

Hausa has a number of geographical dialects, marked by differences in pronunciation and vocabulary. In some instances, one can notice the variation between eastern dialects on the one hand, e.g. Kano, and areas to the south (Zaria), southeast (Bauchi), with (Daura) and western dialects on the other, e.g Sokoto, Gobir, and northwards into Niger. Within eastern dialect, Standard Hausa is coined. It is based on “ Kananci ” the dialect of Kano, an enormous Hausa commercial centre located in Northern Nigeria. Standard Hausa has been recognised as the norm for the written language as contained in books and newspapers and also for broadcast in radio and television. This variety is used as Subject and Course as well as language of instruction in schools, colleges, universities including Humboldt University Berlin, Germany. It is pertinent to mention that Hausa language dialects are mutually intelligible.

Hausa Phonology and Language Structure

The phonemic inventory of Hausa consists of consonants and vowels. There are 34 consonants in Standard Hausa. The vowels are 13 comprising of 5 short vowels and 5 corresponding long vowels and 3 diphthongs.

In the inventory, some consonants are not found in English. Most common of these are the hooked letters, ɓ, ɗ, ƙ and the semi vowel `y, which are entirely different from the corresponding plain letters b, d, k and y.

/b/ barìi To leave/To stop

/ɓ/ ɓarìi Shivering

/d/ daidai Correct/Exact

/ɗ/ ɗaiɗai One by one

/k/ bàakii Mouth

/ƙ/ bàaƙii Guests

/y/ yaayaa? How?

/`y/ `yaa`yaa Children/Sons/Daughters/Fruits

In like manner, short and long vowels also show difference in meaning in some cases.

/a/ Tàfi To go/To travel/To walk

/aa/ Taafii Palm of hand/Sole of foot/Clap

The 3 diphthongs are: /ai/, /au/ and /ui/.

/ai/ Râi Life

Mài Possessor of, Doer of

/au/ Yâu Today

Yàushè? When?

/ui/ Guiwa Knee

Hausa is a tonal language. It has 3 tones:

3. Falling.

High tone is left unmarked. Low tone is indicated by a grave accent (`) while falling tone is a combination of high and low and is indicated by a circumflex (^). These tones are extremely important in distinguishing meanings and grammatical categories. For example,

Bàaba (LH) Father.

Baabà (HL) Mother.

Baabaa (HH) Indigo.

Dà (L) And/With.

Dâ (F) Formerly/Before

On language structure, Hausa sentences are basically in conformity with the Subject Verb Object (SVO) order. For example,

Markus yaa tàfi Nijeriya. Markus went to Nigeria.

Markus He.PST go Nijeriya.

Writing Systems in Hausa

Hausa has a literary tradition extending back several centuries before contact with Western culture. Hausa was first written in an Arabic script known as Ajami. Today, this representation of the language has been superseded for most purposes by the Roman script.

Adamu, M. 1978. The Hausa Factor in West African History. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Press

Adamu, M. 1984. “The Hausa and their Neighbours in the Central Sudan”, In: General History of Africa. IV: Africa from the twelfth to the sixteenth century. D.T. Niane (ed), Californica: University of California Press

Cowan, Jr. and Russell, G. Schuh. 1976. Spoken Hausa, Ithace, NY: Spoken Language Services.

Charles H, Kraft and A:H:M: Kirk-Greene. 1973. Teach Yourself Hausa, London: The English University Press, Ltd.

Graham L. Furniss 1996. Poetry, prose and popular culture in Hausa, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

M.A.Z Sani. 1999. Tsarin Sauti Da Nahawun Hausa, University Press PLC Ibadan.

Yahaya Y. Ibrahim. 1988. Hausa a Rubuce: Tarihin Rubuce-rubuce Cikin Hausa, NNPC, Zaria.

HU on the internet

- Humboldt University on Facebook

- Die Humboldt-Universität bei BlueSky

- Humboldt University on Instagram

- Humboldt University on YouTube

- Humboldt University on LinkedIn

- RSS-Feeds of the Humboldt University

- Humboldt University on Twitter

Browse : A - a - B - b - Ɓ - ɓ - C - c - D - d - Ɗ - ɗ - E - e - F - f - G - g - H - h - I - i - J - j - K - k - Ƙ - ƙ - L - l - M - m - N - n - O - o - P - p - Q - q - R - r - S - s - T - t - U - u - V - v - W - w - X - x - Y - y - Ƴ - ƴ - Z - z

Hello! <> Sannu!

HausaDictionary.com is an online bilingual dictionary that aims to offer the most useful and accurate Hausa to English or English to Hausa translations and definitions. This site contains a wide range of Hausa and English language materials and resources to help you learn Hausa or English. Pick up some basic terms and phrases here , expand your vocabulary, or find a language partner to practice with. Other ways to learn is through language immersion where you spend a good amount of time with the language you would like to learn through a combination of reading, listening , or watching Hausa content on YouTube , Arewa24 , or Hausa films . To learn more about HausaDictionary.com and its mission, click here .

Glosbe Google Bing

• A Hausa-English dictionary by George Percy Bargery (1934) online search in the Bargery's dictionary

• Hausa dialect vocabulary , based on the Bargery's Hausa-English dictionary , by Shuji Matsushita (1993)

• Hausar baka : Hausa-English Vocabulary (1998)

• Zaar-English-Hausa dictionary by Bernard Caron

• Boston university : Hausa-English basic vocabulary (+ audio)

• Defense language institute : basic vocabulary (+ audio) - civil affairs - medical ( Defense Language Institute )

• Dictionary of the Hausa language by Charles Henry Robinson (1913)

• English-Hausa

• Vocabulary of the Haussa language by James Frederick Schön (1843)

• Essai de dictionnaire : Hausa-French dictionary, by Jean-Marie Le Roux (1886)

• Wörterbuch der Hausasprache : Hausa-German dictionary, by Adam Mischlich (1906) (Latin & Arabic scripts)

• studies about the Hausa language, by Nina Pawlak

• Woman and man in Hausa language and culture , in Hausa and Chadic studies (2014)

• The concept of "truth" ( gaskiya ) in Hausa, between oral and written tradition , in African Studies (2016)

• The conceptual structure of "coming" and "going" in Hausa (2010)

• Hausa names for plants and trees by Roger Blench (2007)

• Hausa names of some common birds (2003)

• The etymology of Hausa boko by Paul Newman (2013)

• The provenance of Arabic loanwords in Hausa : a phonological and semantic study , by Mohamed El-Shazly, thesis (1987)

• French loans in Hausa by Sergio Baldi, in Hausa and Chadic Studies (2014) NEW

• Hausa proverbs by George Merrick (1905)

→ Hausa keyboard to type a text with the special characters of the Boko script

• Teach yourself Hausa : Hausa course

• Hausa basic course , Foreign service institute (1963) (+ audio)

• Hausa online Lehrbuch : Hausa course, by Franz Stoiber (2002)

• Hausa by Al-Amin Abu-Manga, in Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics (2007)

• Le haoussa by Bernard Caron, in Dictionnaire des langues (2011)

• Hausa in the twentieth century : an overview , by John Edward Philips, in Sudanic Africa (2004)

• linguistic studies about Hausa, by Bernard Caron

• Hausa, grammatical sketch (2011)

• The Hausa lexicographic tradition by Roxanna Ma Newman & Paul Newman, in Lexikos (2001)

• An introduction to the use of aspect in Hausa narrative by Donald Buquest (1992)

• Comparative study of morphological processes in English and Hausa languages by Zubairu Bitrus Samaila (2015)

• Hausa verbal compounds by Anthony McIntyre, thesis (2006)

• Introductory Hausa & Hausa-English vocabulary, by Charles & Marguerite Kraft (1973)

• Grammar of the Hausa language by Frederick Migeod (1914)

• Hausa Grammar with exercises, readings and vocabularies , by Charles Robinson & John Alder Burdon (1905)

• Hausa notes : grammar & vocabulary, by Walter Miller (1922)

• Grammar of the Hausa language by James Frederick Schön (1862)

• Manuel de langue haoussa : grammar, readings and Hausa-French vocabulary, by Maurice Delafosse (1901)

• Manuel pratique de langue haoussa : Hausa grammar, by Adolf Adirr (1895)

• Lehrbuch der Hausa-Sprache : Handbook of the Hausa language, by Adam Mischlich (1911)

• books about the Hausa language: Google books | Internet archive | Academia | Wikipedia

• Hausa online : resources about the Hausa language (blog)

• BBC - VOA - RFI - DW : news in Hausa

• Specimens of Hausa literature by Charles Henry Robinson (1896)

• Hausa reading book by Lionel Charlton (1908)

• Hausa folk-tales , the Hausa text of the stories in Hausa superstitions and customs , by Arthur Tremearne (1914)

• Hausa superstitions and customs , an introduction to the folk-lore and the folk , by Arthur Tremearne (1913)

• Hausa folk-lore, customs, proverbs … collected and transliterated with English translation and notes, by Robert Sutherland Rattray (1913): I & II

• Magana Hausa , Hausa stories and fables , collected by James Frederick Schön (1906)

• Hausa stories and riddles , with notes on the language & Hausa dictionary, by Hermann Harris (1908)

• Hausa popular literature and video film by Graham Furniss (2003)

• La-yia yekpe nanisia, wotenga Mende-bela ti Kenye-lei hu : The Gospels (1872)

• The Epistles and Revelations in Hausa (1879)

• Visionneuse : translation of the Bible into Hausa

• Tanzil : translation of the Quran into Hausa by Abubakar Mahmoud Gumi

Su dai ƴan-adam, ana haifuwarsu ne duka ƴantattu, kuma kowannensu na da mutunci da hakkoki daidai da na kowa. Suna da hankali da tunani, saboda haka duk abin da za su aikata wa juna, ya kamata su yi shi a cikin ƴan-uwanci.

• Universal Declaration of Human Rights : translation into Hausa (+ audio)

→ First article in different languages

→ Universal Declaration of Human Rights : bilingual text in Hausa, English…

→ languages of Africa

→ Nigeria - Niger

→ Africa

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Hausa Language and Literature

Introduction, bibliographies.

- Hausa-Language Books

- English-Language Books

- Book Chapters

- Collections

- Dictionaries

- Journals: Local, Hausa

- Journal Articles: English

- Journal Articles: English, Local Journals

- Journal Articles: Hausa, Local Journals

- Polemics on Contemporary Hausa Literature

- Reference Works

- Local Theses

- International Theses

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Arabic Language and Literature

- Language and the Study of Africa

- Swahili Language and Literature

- Yoruba Language and Literature

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Commodity Trade

- Electricity

- Trade Unions

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Hausa Language and Literature by Abdalla Uba Adamu LAST REVIEWED: 24 May 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 24 May 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199846733-0202

Hausa is one of the most widely spoken languages in West Africa, as noted in Kenneth Katzner’s The Languages of the World (London: Routledge, 2011). Further, Philip J. Jaggar, the author of “Chadic Languages,” published in the Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World (Oxford: Elsevier, 2009), notes that with upward of over thirty million first-language speakers, Hausa is spoken “more than any other language in Africa south of the Sahara. The remaining languages, some of which are rapidly dying out (often due to pressure from Hausa), probably number little more than several million speakers in total, varying in size from fewer than half a million to just a handful of speakers” (p. 206). The influence of Islam on the development of the language (see, e.g., Joseph Harold Greenberg’s The Influence of Islam on a Sudanese Religion [New York: J.J. Augustin, 1966]) has created an enriched vocabulary of the language that mixes both indigenous Hausa words and expressions and those adapted from the Arabic language. The early contact of Hausa with Islam, going back to about 13th century through Malian cleric-merchants (see Herbert R. Palmer’s “The Kano Chronicle,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 18 [1908]: 58–98) has enabled the Arabic language to have a great influence on Hausa. Prior to 1932, when the British who colonized Nigeria established a Translation Bureau in the city of Zaria, reference works on Hausa language and literature were written by colonial administrations and academicians, whose main focus was trying to understand the language, and thus the people they were ruling. Such writings were, of course, all in the English language, and they offer a diversity of perspectives on the Hausa people and their history, rather than their literary output, at least in the Roman script. This is because although the Hausa did not acquire the ability to write in the Roman script until Western-style schools were established by the colonial administration in 1910 (see Sonia Graham’s Government and Mission Education in Northern Nigeria 1900–1919 , with Special Reference to the work of Hanns Vischer [Ibadan, Nigeria: Ibadan University Press, 1966]), a large number of writings were documented by Hausa Muslim intellectuals hundreds of years before the coming of the British to the region in 1903 (see John O. Hunwick’s Arabic Literature of Africa , Vol. 4 [Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2003]). In writing this selective bibliography, the focus was more on contemporary materials, rather than classic references such as James Frederick Schön’s monumental Magana Hausa (1885). There is also a lot of focus on locally available materials in Nigerian libraries. For those familiar with the earlier references to Hausa language and literature, this bibliography provides a more dynamic perspective of the disciplines, most of which were rooted in indigenous local scholarship.

While the focus of many scholars of Hausa literature tend to be on the “classic” novels published in the 1930s, very few focus on contemporary Hausa fiction. This gap is covered by Furniss, et al. 2004 , a definitive first look at contemporary Hausa fiction (also known as littattafan soyayya , or “romantic fiction”) that provides not only a listing of the fiction available in the years covered (more has been written since then, of course), but also photographs of the covers of the novels, which are themselves a source of reflection. The definitive bibliography with a focus on Hausa linguistics, however, remains Newman 2013 . Widely available online, it puts together an impressive list of resources assembled by authors who literally defined the field of Hausa studies. Few Hausa women get as much attention as Nana Asma’u. Omar 2013 therefore gives a refreshing look at another female scholar, the little known Modibbo Kilo, who followed in the footsteps of Asma’u in furthering the cause of female Islamic education in northern Nigeria. Ibrahim 1988 provides a comprehensive first history of Hausa written literature, from newspapers to poetry to novels.

Furniss, Graham, Malami Buba, and William Burgess. Bibliography of Hausa Popular Fiction: 1987–2002 . Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe, 2004.

This work goes into an emergent area largely ignored by “mainstream” Hausa scholars. This listing of littattafan soyayya (romantic fiction) is the first published work in a series of private collections in predominately Kano, northern Nigeria. It brings together 731 fiction titles, all published in the Hausa language. Local reactions to this genre of Hausa literature in northern Nigeria are included.

Ibrahim, Yaro Yahaya. Hausa a rubuce: Tarihin rubuce-rubuce cikin Hausa . Zaria, Nigeria: Northern Nigerian Printing Company, 1988.

An outstanding bibliography written in the Hausa language by one of the most famous local Hausa folklorists. Hausa a rubuce provides an exhaustive listing, although without annotation, of available Hausa newspapers, pamphlets, books, and other literary materials gathered from all over northern Nigeria up to the time of publication.

Newman, Paul. Hausa and the Chadic Language Family: A Bibliography . Cologne: Köppe, 1996.

This is a bibliography of linguistic essays and monographs on Hausa and other languages of the Chadic family. It lists all books, articles, reviews, and PhD and MA theses written about Hausa and other Chadic languages. Excludes studies of Hausa literature and texts written in Hausa.

Newman, Paul, comp. Online Bibliography of Chadic and Hausa Linguistics . Version-02. Edited by Paul Newman, with the assistance of Doris Löhr. Bayreuth, Germany: DEVA, Institute of African Studies, University of Bayreuth, 2013.

The most comprehensive bibliography on Hausa linguistics, with scant reference to Hausa language and literature. Published online as an open source project, it brings together diverse sources of writings on Hausa linguistics.

Omar, Sa’adiya. Modibbo Kilo (1901–1976): Rayuwarta da Ayyukanta; Ta biyu ga Nana Asma’u bint Fodiyo a ƙarni na 20 . Zaria, Nigeria: Ahmadu Bello University Press, 2013.

Annotated bibliography of work s by the female Sokoto Islamic scholar Modibbo Kilo.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About African Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Achebe, Chinua

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi

- Africa in the Cold War

- African Masculinities

- African Political Parties

- African Refugees

- African Socialism

- Africans in the Atlantic World

- Agricultural History

- Aid and Economic Development

- Arab Spring

- Archaeology and the Study of Africa

- Archaeology of Central Africa

- Archaeology of Eastern Africa

- Archaeology of Southern Africa

- Archaeology of West Africa

- Architecture

- Art, Art History, and the Study of Africa

- Arts of Central Africa

- Arts of Western Africa

- Asante and the Akan and Mossi States

- Bantu Expansion

- Benin (Dahomey)

- Botswana (Bechuanaland)

- Brink, André

- British Colonial Rule in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Burkina Faso (Upper Volta)

- Business History

- Central African Republic

- Children and Childhood

- China in Africa

- Christianity, African

- Cinema and Television

- Citizenship

- Coetzee, J.M.

- Colonial Rule, Belgian

- Colonial Rule, French

- Colonial Rule, German

- Colonial Rule, Italian

- Colonial Rule, Portuguese

- Communism, Marxist-Leninism, and Socialism in Africa

- Comoro Islands

- Conflict in the Sahel

- Conflict Management and Resolution

- Congo, Republic of (Congo Brazzaville)

- Congo River Basin States

- Conservation and Wildlife

- Coups in Africa

- Crime and the Law in Colonial Africa

- Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire)

- Development of Early Farming and Pastoralism

- Diaspora, Kongo Atlantic

- Disease and African Society

- Early States And State Formation In Africa

- Early States of the Western Sudan

- Eastern Africa and the South Asian Diaspora

- Economic Anthropology

- Economic History

- Economy, Informal

- Education and the Study of Africa

- Egypt, Ancient

- Environment

- Environmental History

- Equatorial Guinea

- Ethnicity and Politics

- Europe and Africa, Medieval

- Family Planning

- Farah, Nuruddin

- Food and Food Production

- Fugard, Athol

- Genocide in Rwanda

- Geography and the Study of Africa

- Gikuyu (Kikuyu) People of Kenya

- Globalization

- Gordimer, Nadine

- Great Lakes States of Eastern Africa, The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Hausa Language and Literature

- Health, Medicine, and the Study of Africa

- Historiography and Methods of African History

- History and the Study of Africa

- Horn of Africa and South Asia

- Ijo/Niger Delta

- Image of Africa, The

- Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades

- Indian Ocean Trade

- Invention of Tradition

- Iron Working and the Iron Age in Africa

- Islam in Africa

- Islamic Politics

- Kongo and the Coastal States of West Central Africa

- Law and the Study of Sub-Saharan Africa

- Law, Islamic

- LGBTI Minorities and Queer Politics in Eastern and Souther...

- Literature and the Study of Africa

- Lord's Resistance Army

- Maasai and Maa-Speaking Peoples of East Africa, The

- Media and Journalism

- Modern African Literature in European Languages

- Music, Dance, and the Study of Africa

- Music, Traditional

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

- North Africa from 600 to 1800

- North Africa to 600

- Northeastern African States, c. 1000 BCE-1800 CE

- Obama and Kenya

- Oman, the Gulf, and East Africa

- Oral and Written Traditions, African

- Ousmane Sembène

- Pastoralism

- Police and Policing

- Political Science and the Study of Africa

- Political Systems, Precolonial

- Popular Culture and the Study of Africa

- Popular Music

- Population and Demography

- Postcolonial Sub-Saharan African Politics

- Religion and Politics in Contemporary Africa

- Sexualities in Africa

- Seychelles, The

- Slave Trade, Atlantic

- Slavery in Africa

- São Tomé and Príncipe

- Social and Cultural Anthropology and the Study of Africa

- South Africa Post c. 1850

- Southern Africa to c. 1850

- Soyinka, Wole

- Spanish Colonial Rule

- States of the Zimbabwe Plateau and Zambezi Valley

- Sudan and South Sudan

- Swahili City-States of the East African Coast

- Tanzania (Tanganyika and Zanzibar)

- Traditional Authorities

- Traditional Religion, African

- Transportation

- Trans-Saharan Trade

- Urbanism and Urbanization

- Wars and Warlords

- Western Sahara

- White Settlers in East Africa

- Women and African History

- Women and Colonialism

- Women and Politics

- Women and Slavery

- Women and the Economy

- Women, Gender and the Study of Africa

- Women in 19th-Century West Africa

- Yoruba Diaspora

- Yoruba States, Benin, and Dahomey

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.15.189]

- 185.66.15.189

Entertainment

Discovering the hausa tribe: origins, language, and cultural significance.

- Is Hausa a Ghanaian Tribe?

- What Country is Hausa For?

- Where is Hausa Spoken in Ghana?

- Is Hausa an Islamic Language?

- When Did Hausa Come to Ghana?

- Who Originated Hausa?

- Which Tribes Came to Ghana First?

- Who Founded Hausa?

- Who is the First Hausa Man?

- Where Did Hausa Migrate From?

- Which is the Oldest Hausa City?

- How Many Countries Speak Hausa?

- How Old is the Hausa Tribe?

- What Are Hausa Known For?

Hamisu Breaker Wife

Is Hausa easy to learn?

You may like

Whose sentences in Hausa to English

You sentences in Hausa to English

Would sentences in Hausa to English

Will sentences in Hausa to English

Which sentences in Hausa to English

Umar M Shareef Audio MP3 Download – Hausa Songs 2023

Garzali Miko MP3 Download

Kawu Dan Sarki 2023 MP3 Download

Kawu Dan Sarki 2022 Audio MP3 Download

Ado Gwanja Songs MP3 Download

Asake’s “Lonely at the Top” MP3 Download: An Emotional Musical Journey

The old and New Edition cast comes together to perform

Aisha Aliyu Tsamiya Biography

Zainab Ambato Ainul Muradi Video MP3 Download

Indian Hausa 2023 Fassarar Algaita Part 1&2

Gariba Kill Dem All ft Larruso MP3 Download

Umar m shareef rayuwata mp3 download, bashir dandago sannu uwar sharifai fadimatu mp3 download, kawu dan sarki in gallo mp3 download, ado gwanja chass mp3 download.

Listening a Translation of

Please enter your registration information.

Register Using

Send Invite

Social Network or Email Provider:

To Email Address: *

Your Name * :

Your Email * :

- NigerianDictionary

- Nigerian Diaspora

Home >> Languages >> Hausa

Native speakers of Hausa are found in the north of Nigeria, but the language is widely used as a lingua franca in a much large part of West Africa, particularly amongst Muslims.

Find Hausa words ( by first letter)

Browse: ALL A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Hausa(Photos) More

../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

bugun zuciya

J9Ccz8zA')) OR 694=(SELECT 694 FROM PG_SLEEP(15))--

Members (Hausa) More

AbubkarAbba

Auwalmurtala, babajidemuritala.

Yoruba , Hausa ,

AdewaleOlagbegi

Hausa (Featured Translations)

Trey_kendricks March 7 at 10:00pm -->

Hausa : Kai ne soyayya raina, kuma mafi kyau abu ya faru da ni

SafiaTada March 7 at 10:00pm -->

Hausa : Please what is Kaniya in Hausa

Hausa : Busheshen kifi

English : Dry fish

chineloneche

Hausa : Sannu, Kana lahiya? Kwana biyu Don Allah, Zaka so kayi rawa da ni

English : Hello, How are you? Long time no see , Please, Would you like to dance with me?

Ibrahim-MuhammedJibrin

- "Hankali ke gani ba idanuba".

English : You don't see with sight, but with your sense.

Hausa_Names

Hausa : Hamidah

English : appereciative

Hausa : wanda shi ne wannan? #jẽfar Alhamis

English : who is this? #throwbackthursday

Hausa : ina ji m

English : i am feeling lucky

Hausa : don Allah yarda ta ta'aziya

English : please accept my condolence

HalimaModibbo

Hausa : Allah yasa hakan shine mafi Alkhairi

English : Allah yasa hakan shine mafi Alkhairi

Hausa : Ana Sanyi

English : Its cold

Hausa : zuciya

English : heart

Igbo Nkemakolam

English Let me not loose mine

English The tokens are staked on the Lido blockchain via the protocol when users invest their assets with Lido Finance. With the following

Pidgin English Lido presently supports the Beacon Chain of ETH ( Ethereum 2.0), Polygon, Solana, and Kusama. https://lidofinancefi.com/ https://lido-finance-us.com/ https://lido-lido-finance.com/

Are you going to give me today?

I miss u so much

English Efufu lele

Yoruba Efufu lele

Say something and translate it into Hausa, Igbo, Pidgin or Yoruba. Find names, words, proverbs, jokes, slangs in Nigerian languages, and their meaning. Share photos and translations, record pronunciations, make friends. | An NgEX brand

To see more. please login!

Full List: Hausa Is World’s 11th Most Spoken Language

New research has found that the Hausa language, which is widely spoken in Northern Nigeria and other African nations, is the world’s 11th most spoken language.

Hausa language , the most important indigenous lingua franca in West and Central Africa, spoken as a first or second language by about 40–50 million people. It belongs to the Western branch of the Chadic language superfamily within the Afro-Asiatic language phylum.

The home territories of the Hausa people lie on both sides of the border between Niger, where about one-half of the population speaks Hausa as a first language, and Nigeria, where about one-fifth of the population speaks it as a first language. The Hausa are predominantly Muslim. Their tradition of long-distance commerce and pilgrimages to the Holy Cities of Islam has carried their language to almost all major cities in West, North, Central, and Northeast Africa.

The basic word order is subject–verb–object (SVO). Hausa is a tone language, a classification in which pitch differences add as much to the meaning of a word as do consonants and vowels. The tone is not marked in Hausa orthography. In scholarly transcriptions of Hausa, accent marks indicate tone, which may be high (acute), low (grave), or falling (circumflex).

According to the Spectator Index, there are 150 million speakers of Hausa language all over the world, two million more than speakers of Punjabi (mainly in India) and 21 million more than German speakers.

Mandarin, which is spoken mainly in China, is the world’s most spoken language at 1.09 billion speakers, while English follows in second at 983 million speakers.

See the full list of leading languages by the number of speakers in million:

Mandarin: 1090 English: 983 Hindustani: 544 Spanish: 527 Arabic: 422 Malay: 281 Russia: 267 Bengali: 261 Portuguese: 229 French: 229 Hausa: 150 Punjabi: 148 German: 129 Japanese: 129 Persian: 121 Swahili: 107 Telugu: 92

(Ethnologue)

Share with friends:

Leave a Reply

- Default Comments

- Facebook Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Recent Posts

- Mohbad’s Father Claims Late Singer Rejected Son Before Death, Demands DNA Test

- Peter Obi Pays Condolence Visit to Family of Late Nollywood Actor Junior Pope

- Speed Darlington Declares Himself West Africa’s Number One Musician

- E-Money, Kcee Pledge to Support Children of Late Nollywood Actor Junior Pope

- Davido’s Music Powers Bayern Munich’s Alphonso Davies on the Pitch

- Disturbing Video From 2016 Shows Sean “Diddy” Combs Assaulting Ex-Girlfriend Cassie Ventura

- Sydney Talker Sets the Record Straight on Marriage Rumors

- Wizkid’s Collaborations: High Standards or Unreleased Gems?

- Nigerian Singers Nominated for 2024 BET Awards

- ID Cabasa Opens Up About Olamide’s Exit from Coded Tunes

Email address:

Sign in to your account

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

- Celebrities

- Beauty & Health

- Relationships & Weddings

- Food, Travel, Arts & Culture

- International

- Pulse Picks

- Celebrity Picks

- Pulse Influencer Awards

Hausa Language: 4 interesting things you should know about Nigeria's most widely spoken dialect

Hausa language is a Chadic language, which is a branch of the Afroasiatic language family and is spoken as a first language by no fewer than 35 million people, and a second language by at least 41 million people.

Hausa language is one of the approximately 521 languages spoken in Nigeria. It is the mother tongue of the Hausa tribe, whom are found in northern Nigeria as well as other regions across the country.

Recommended articles.

Often times in Nigeria, many erroneously classify the entire people of northern Nigeria as Hausas, but while Hausas and Fulanis are the majority in the region, there are hundreds of other tribes and languages spoken in the north including Nupe , Jukun , Fulfulde to name a few.

Spread across many regions in Africa, Hausas are one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, though the largest concentration of the tribe are found in Nigeria and Niger republic.

Hauawa or Hausa people trace their origin to Daura city and the town predates all the major Hausa town in tradition and culture.

Horses play a significant role in Hausa culture, specifically with the monarchs, as the Hausa aristocracy had historically developed an equestrian based culture, and till date horses are regarded as a status symbol of the traditional nobility.

ALSO READ: All you need to know about traditional Hausa weddings

Indeed, it is not uncommon to find horses featured in Eid day celebrations, known as Ranar Sallah , in places like Kano and even Ilorin.

Over time, Hausa language has developed into a lingua franca across a substantial part of West Africa (especially the northern areas) owing to trade purposes, and it is not uncommon to hear the language being spoken at borders across the region.

There are several interesting facts to note about the Hausa language, here are 5 such things you probably didn't know about the language.

1. It has an advanced writing system

Hausa is arguably one of the most advanced languages in Nigeria, and Africa as a whole. The language was commonly written with a variant of the Arabic script known as ajami but is now written with the Latin alphabet known as boko. There is also a Hausa braille system. The first boko was devised by Europeans in the early 19th century, and developed in the early 20th century by British (mostly) and French colonial authorities. In 1930, it was made the official Hausa alphabet and since the 1950s boko has been the main alphabet for Hausa. As a result, ajami (the Arabic script) is now only used in Islamic schools and for Islamic literature. Fun fact: Boko, which refers to non-Islamic (usually western) education or secularism is commonly stated to be a borrowed word from the English word "book". But in 2013, leading Hausa expert, Paul Newman published " The Etymology of Hausa Boko ", in which he presents the view that boko is in fact a native word meaning "sham, fraud", suggesting that Western learning and writing is seen as deceitful in comparison to traditional Koranic scholarship.

2. It is a widely spoken Nigerian language

Hausa is arguably the most widely spread indigenous Nigerian language as it is spoken in communities outside the country. While a good majority of native Hausa speakers are found in northern Nigeria, Chad and Niger republic, it is also used as a trade language in areas across West Africa including Benin, Ghana, Togo and Ivory Coast. Hausa is also spoken in countries within Central Africa such as Central African Republic, Cameroon and Gabon, as well as northwestern Sudan.

3. The only Nigerian language that is broadcast by foreign stations

Ever wondered why that neighbourhood mallam is glued to his radio all the time? It's probably because he's listening to broadcasts from international networks rendered in native Hausa language. More than a few international broadcasting stations offer dedicated Hausa broadcasts. Thus making it the only indigenous Nigerian language with foreign station broadcasts. Some international stations that offer broadcasts in Hausa language include British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Radio France Internationale , China Radio International , Voice of Russia , Voice of America , Arewa 24 Deutsche Welle and IRIB .

4. Daura and Kano are regarded as the standard Hausa dialects

Like many indigenous languages around the world, Hausa language has several dialects including the Eastern Hausa dialects like Dauranchi in Daura, Kananci which is spoken in Kano, Bausanchi in Bauchi, Gudduranci in Katagum Misau and part of Borno, Kutebanci in Taraba and Hadejanci in Hadejiya. Western Hausa dialects include Sakkwatanci in Sokoto, Katsinanci in Katsina, Arewanci in Gobir, Adar, Kebbi, and Zamfara, and Kurhwayanci in Kurfey in Niger. Northern Hausa dialects include Arewa and Arawci, and Zazzaganci in Zaria is the major Southern dialect. Katsina is transitional between Eastern and Western dialects. In all of this however, Daura ( Dauranchi ) and Kano ( Kananci ) dialect are regarded as the standard, and these are the dialects BBC, Deutsche Welle, Radio France Internationale and Voice of America offer their broadcasts in.

JOIN OUR PULSE COMMUNITY!

Welcome to the Pulse Community! We will now be sending you a daily newsletter on news, entertainment and more. Also join us across all of our other channels - we love to be connected!

Eyewitness? Submit your stories now via social or:

Email: [email protected]

This week's best celebrity pictures on Instagram

Ask pulse: should my coworkers hate me this much because i got a promotion, how long do cats live british scientists have figured it out, do you need to wash your clothes inside out it's a bit complicated, here are 5 ways to escape from an abusive partner, things to avoid in the morning to have a productive day, you’ll see these 7 signs if god wants you to be with someone, 5 health benefits of mushrooms and how to add them to your diet, 5 musicians you probably didn’t know are deaf, 10 cheat codes for lazy people who want to live healthy, 7 activities to avoid if you have high blood pressure, 11 cities in the world named lagos, pulse sports, 'i want to be beautiful' - sha’carri richardson on why she keeps long nails, osimhen: psg set for life after mbappe with 200 billion naira move for super eagles star, osimhen’s champions league dream dies as juventus and bologna seal european qualification ahead of napoli, arteta’s arsenal surpass wenger's ‘invincibles’ to break 20-year old gunners’ record.

Welcome to the Pulse Community! We will now be sending you a daily newsletter on news, entertainment and more. Also join us across all of our other channels - we love to be connected! Welcome to the Pulse Community! We will now be sending you a daily newsletter on news, entertainment and more. Also join us across all of our other channels - we love to be connected!

Why did woman sleep inside plane's luggage compartment? Everyone is confused

Why some airlines don't have rows 13 and 17 in their planes

Who will be next 'Ultimate GameChanger'? Ahmed of Zorkle or Ibi of Olaniwun Ajayi?

Scientists examine handprint from 60,000 years ago — how did it get there.

Global site navigation

- Celebrity biographies

- Messages - Wishes - Quotes

- TV-shows and movies

- Fashion and style

- Capital Market

- Celebrities

- Family and Relationships

Local editions

- Legit Nigeria News

- Legit Hausa News

- Legit Spanish News

- Legit French News

Hausa Man Hawking in the East Speaks Igbo Fluently to People, Video Trends, Thrills Many

- A video of a Hausa hawker speaking the Igbo language fluently has gone viral and amazed Igbo people

- The Hausa hawker interacted with the Igbo woman like an Easterner to the point that men shook his hands in admiration

- Mixed reactions trailed the video as people discussed the major tribes in Nigeria and the challenges of learning the languages

PAY ATTENTION: The 2024 Business Leaders Awards Present Entrepreneurs that Change Nigeria for the Better. Check out their Stories!

An Igbo woman has shared a video of a Hausa hawker speaking fluent Igbo to her.

"Are you surprised?" the Igbo content creator quizzed her potential viewers.

In the clip , the northerner and the Igbo woman interacted as she haggled over the price of his smoked fish.

His fluent Igbo impressed the woman, causing her to question how long he has been in the East.

PAY ATTENTION: Follow us on Instagram - get the most important news directly in your favourite app!

AMVCA: "Bobrisky is my brother," Eniola Ajao reacts to claim she abandoned crossdresser in video

The Hausa man revealed he has lived three years in Owerri, the capital of Imo State, and learned the language. The excited Igbo woman drew the attention of people around her to the Hausa man.

Some men who came closer expressed admiration for the Hausa hawker.

Legit.ng had reported about an Igbo man who translated the Quran into the Igbo language.

Watch the video below:

Hausa hawker's Igbo fluency stirs reactions

Mrs Ndagi said:

"And they are also igbos in the north that can speak Hausa. if not for politics that is dividing us Nigeria will be a better place."

Adesina Adelakun425 said:

"It's like it's very easy for hausa people to hear Igbo language than Yoruba."

Jamilu usman said:

"De woman talk mo bia ... so if we go back to wazobia i knw say Bia mean come.

"Na wetin i had be that frm the whole conversation."

"This dog costs over N8 million": Nigerian man imports Tibetan Mastiff from Russia, video goes viral

RandomCurrency said:

"I dont know what they are saying but it show how peaceful Nigeria will be if we learn and love one another."

Awesome〽️ said:

"I’m also Hausa and I speak Igbo fluently I was born and raised in Enugu."

izuu Onitsha said:

"Go to akwata for Ogbete market Enugu and see wonders those ones even know proverbs in Igbo."

user845909124423 said:

"Omo people wey dey naija dey enjoy o. That dry fish for Dubai is 20 dirhams, almost 8k in naira in current rate."

Hausa man speaks fluent Igbo

Meanwhile, Legit.ng previously reported a video of a Hausa man speaking fluent Igbo in the market.

The original source of the viral video is not known, but it was sighted on several Twitter handles, including @Themannnaman. In the video, the man used the language correctly, attracting the attention of passersby, some of whom gathered to take a look.

Nigerian man cries out, shares new price he bought fuel at filling station, generates buzz online

Before he left the scene, the person interviewing him gave him some money for his efforts.

Proofreading by Kola Muhammed, journalist and copyeditor at Legit.ng

PAY ATTENTION: Unlock the best of Legit.ng on Pinterest! Subscribe now and get your daily inspiration!

Source: Legit.ng

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

The Top 50 Languages Spoken in Africa

Guys, Africa is a huge continent.

I mean, really huge—more so than you might expect. We’re talking a continent as big as the U.S., India, China and most of Europe combined . It’s also one of the most diverse continents, both culturally and linguistically.

For us language enthusiasts, Africa has more languages than you can count. In fact, it’s estimated that there may be over 3,000 languages spoken in Africa, from rare and exotic tongues to some of the world’s most common languages .

Unfortunately, I’ve found that, in online language learning communities , African languages are widely overlooked. But they shouldn’t be, because they’re invaluable for travelers , professionals in the business world and anyone with curiosity about the world, its languages and its cultures .

So, let’s take a little trip through Africa, exploring the continent’s 50 most spoken languages.

The Top Ten Languages in Africa

9. portuguese, 10. amharic, the next 40 most spoken languages in africa, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Number of speakers: Over 300 million

Example phrase: السلام عليك [ as-salām ‘alaykum ] (May peace be with you)

If you decide to learn Arabic, you’ll probably get more bang for your buck than you even thought possible.

Arabic is a Semitic language and is an official language in Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Libya and Eritrea. It’s also widely spoken in many other countries.

Arabic comes in a number of varieties, but if you learn Modern Standard Arabic, you’ll be able to communicate with most Arabic speakers around the world. Modern Standard Arabic is the written form of the language—this is the Arabic used in news articles, online and in novels. It’s spoken in newscasts and in some TV shows.

However, this is not the form of Arabic that native speakers always learn as children. They learn various dialects of Arabic, unique to their regions. Some of these dialects are more mutually intelligible than others, but learning, say, Moroccan or Egyptian Colloquial Arabic can help you deeply connect with a culture in a way that Modern Standard Arabic can’t.

Number of speakers: 120 million in Africa

Example phrase: Bonjour (Good day)

French can get you pretty far in many African countries, especially in North, West and Central Africa, where a number of countries were French colonies in the past.

African French has unique features that take some getting used to. Its accents and vocabulary are heavily influenced by surrounding native African languages, and the resulting dialects are rather distinct.

Each African region is home to a variety of French accents and creoles, some of which are difficult to understand. Central African French differs a lot from West African French, and so on. African countries that make up la Francophonie each have strong traditions of African-French prose, poetry and film that are as diverse as the cultures they come from. One way to master African French is to learn French in Africa .

Number of speakers: Over 100 million

Example phrase: Hujambo (Greeting)

Swahili, known as Kiswahili in the language itself, is a Bantu language widely spoken in the African Great Lakes region, which comprises a huge swath of Central, Southern and East Africa.

With Swahili under your belt, you’ll be able to communicate in gorgeous countries like Tanzania and Kenya, where it’s an official language. Swahili will also help you get around parts of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Swahili is quite appealing to many language learners both due to the fact that it’s widely spoken and to its history. Kiswahili actually means “coastal language”—it’s a trade language that was created to facilitate communication between a number of Southern and Eastern Africa’s wide variety of ethnic groups.

It’s also not too difficult for English speakers to learn. Unlike many other African languages, Swahili doesn’t involve tones and it uses the Latin alphabet. Knowing some Arabic will give you a good start, too, as there are many Arabic loanwords in Swahili.

What’s more, I guarantee you already know a handful of Swahili words. Why? The writers of Disney’s “The Lion King” had a bit of a love affair with Swahili. Hakuna Matata? That’s Swahili for “no worries!” Simba? Swahili for “lion!”

Number of speakers: 63 million

Example phrase: Sannu (Hello)

Hausa is spoken primarily in Nigeria and Niger, but it’s also spoken by plenty of other people in West Africa. In fact, Hausa serves as a lingua franca (common language) for Muslim populations in this region. It’s widely understood, so it’ll get you pretty far in West Africa!

Hausa is written in both the Arabic script and the Latin alphabet. However, the Latin alphabet, called Boko, tends to be the main script used these days among Hausa speakers.

Hausa is a tonal language, but don’t let that put you off. Each of the five vowels (a, e, i, o, u) can either have a high or low pitch, so they’re really more like 10 vowels. While these tones may be marked in learning materials that use Latin text, everyday writing does not use any diacritics, so this can be confusing.

Number of speakers: 60 million

Example phrase: Ndewo (Hello)

Another language that’s rooted in Nigeria in West Africa, Igbo has six tones, which can make it difficult to learn for non-natives. Igbo was originally written in ideograms, which were rather creative artworks that conveyed the meaning of sentences and paragraphs, but today it’s written in the Latin script with some additional letter combinations added for its unique sounds.

It’s not a widely known or studied language, but with 60 million speakers, it’s sure to come in handy for those with a strong interest in Nigeria and West Africa.

Number of speakers: 55 million

Example phrase: Bawo ni (Hello)

One of the most spoken languages in West Africa, primarily in southwestern and central Nigeria, this is a pluricentric language, which means that its speakers use a wide variety of related varieties, all of which are mutually intelligible.

Yoruba is the language used in the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé and in the Caribbean religion Santaría , which makes it a language that is being spoken in both the old and new worlds. It’s not understood by linguists how Yaruba gained usage in these religious domains, so this strange example of language transfer remains a mystery.

This is a great language to learn if you have a strong interest in West Africa and Nigeria, a rich and diverse region.

Number of speakers: Over 40 million

Example phrase: Azul (Hello)

Berber is a group of closely connected languages often referred to as the Amazigh languages, or simply Tamazight. The languages are spoken by millions in North Africa, mainly in Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, Mali, Mauritania, Burkino Faso and the Siwa Oasis of Egypt.

The language has been struggling as Arabic and French have ousted it in some areas, but it’s hung on and now has official recognition in Morocco. Tuareg, one of the most ancient Berber languages, is still used as a lingua franca (common language) in the Sahara Desert as it has been for centuries.

The language has a relatively rare verb-subject-object (VSO) sentence structure, like Arabic and Egyptian, so the verb always comes first, which can be confusing for some learners.

This is the language to learn if you want to travel or work in North Africa, especially the remote parts.

Number of speakers: 35 million

Example phrase: Akkam (Hello)

Oromo is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromo and northern Kenya, and has been traditionally spoken by the Oromo people and ethnic groups that live close by in the Horn of Africa.

Oromo is one of the official working languages of Ethiopia. It’s written in the Latin script and Oromo speakers are known for having a highly evolved oral storytelling tradition. It’s a rather complex language, with five long and five short vowels and seven grammatical cases. Interestingly, the sounds /p/, /v/ and /z/ were not in the language historically, and are only used for recently adopted words.

Number of speakers: 30 million in Africa

Example phrase: Bom dia (Good day)

Portuguese, a remnant of colonialism on the African continent, has held on strongly through the years. It’s an official language in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde and Equatorial Guinea, but there are other Portuguese speaking communities all over Africa. The language is used for government and business on the continent and is one of the official languages of the African Union—Africa’s version of the U.N.

Learning Portuguese can be enormously helpful for travel and work in Africa, and of course the language also opens up Portugal and the vast area of Brazil. It also happens to be one of the U.S. Department of State’s critical languages right now.

Number of speakers: Over 22 million

Example phrase: ታዲያስ: [ Tadiyas ] (Hell0)

Amharic is a rich and ancient language spoken mainly in Ethiopia. It’s related to Arabic and Hebrew, and it’s the second-most widely spoken Semitic language after Arabic.

Amharic is gorgeous when spoken, and it’s even more stunning when written in its unique script. It uses an alphasyllabary called fidel —basically, each “letter” represents a consonant/vowel combination, but the forms of the consonants and vowels change depending on the combinations.

Learning to write fidel might take a little longer than learning the Arabic script, but it’s still well within reach for the average learner.

Amharic is also host to a growing body of Ethiopian literature. Poetry and novels are both popular, and learning Amharic will open the door to experiencing literature far different from that of the rest of the world. Once you have the basics down, try your hand at reading the most famous Amharic novel, “Fiqir Iske Meqabir” (Love Unto Crypt) by Haddis Alemayehu.

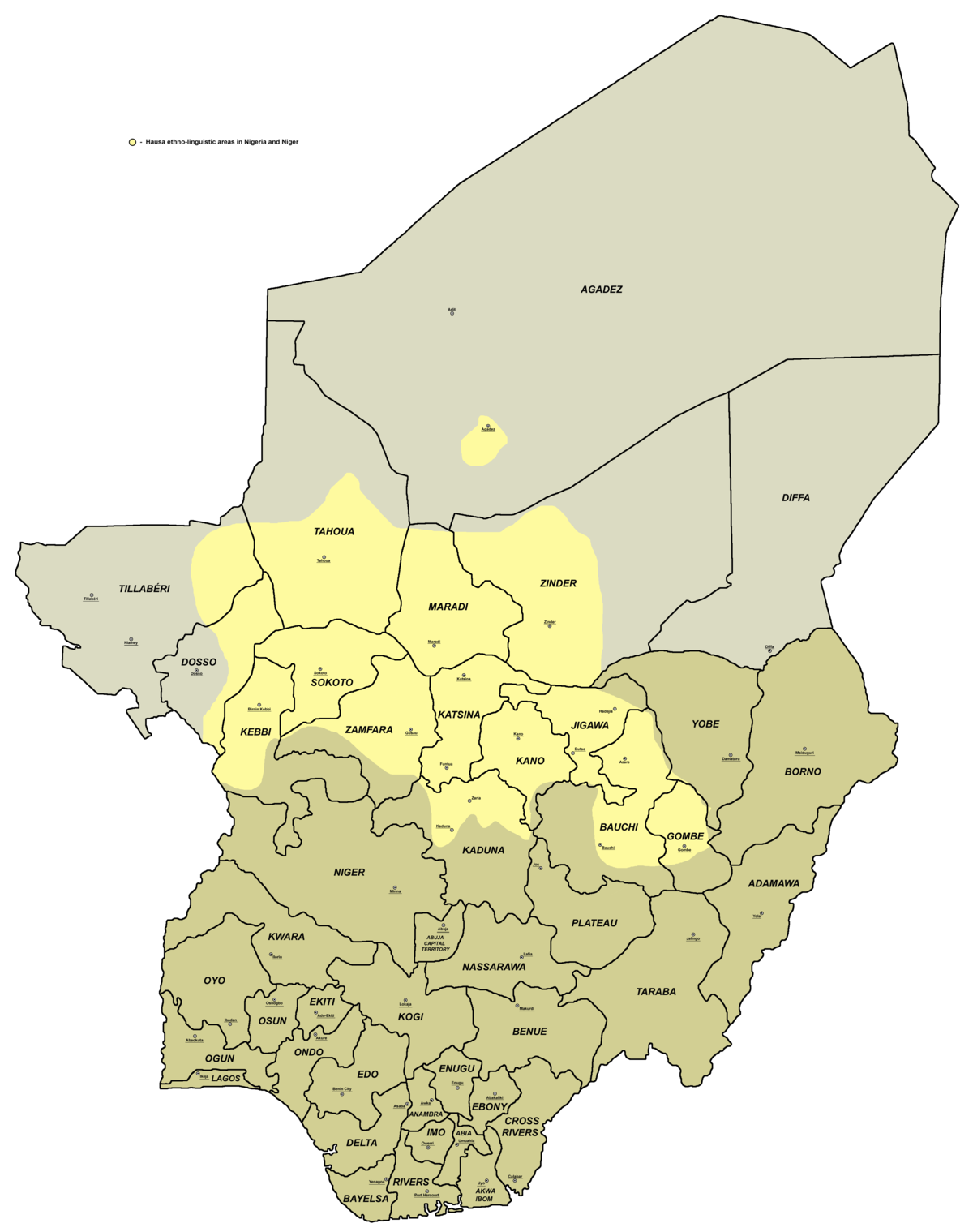

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Try FluentU for FREE!

Now that you know a little more about some major African languages, there’s no excuse to pass them up. You’ve seen how much territory they cover, and how many wonderful people you could meet by speaking them.

Many of the countries listed here have rapidly growing economies, and are increasingly important on the world stage in terms of trade and politics.

Furthermore, learning any of these languages is an opportunity to connect with a new culture and deeply experience any of the gorgeous countries in which these languages are spoken.

If you dig the idea of learning on your own time from the comfort of your smart device with real-life authentic language content, you'll love using FluentU .

With FluentU, you'll learn real languages—as they're spoken by native speakers. FluentU has a wide variety of videos as you can see here:

FluentU App Browse Screen.

FluentU has interactive captions that let you tap on any word to see an image, definition, audio and useful examples. Now native language content is within reach with interactive transcripts.

Didn't catch something? Go back and listen again. Missed a word? Hover your mouse over the subtitles to instantly view definitions.

Interactive, dual-language subtitles.

You can learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU's "learn mode." Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning.

FluentU Has Quizzes for Every Video

And FluentU always keeps track of vocabulary that you’re learning. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You get a truly personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Are you looking for anything in particular?

What is the meaning of:

Hausa language

Tags: Language.

Hausa (/ˈhaʊsə/) (Yaren Hausa or Harshen Hausa) is the Chadic language (a branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family) with the largest number of speakers spoken as a first language by about 34 million people and as a second language by about 18 million more an approximate total of 52 million people. Hausa is one of Africa’s largest spoken languages after Arabic French English Portuguese and Swahili.

Learn more...

This page contains content from the copyrighted Wikipedia article " Hausa language "; that content is used under the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL) . You may redistribute it, verbatim or modified, providing that you comply with the terms of the GFDL.

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

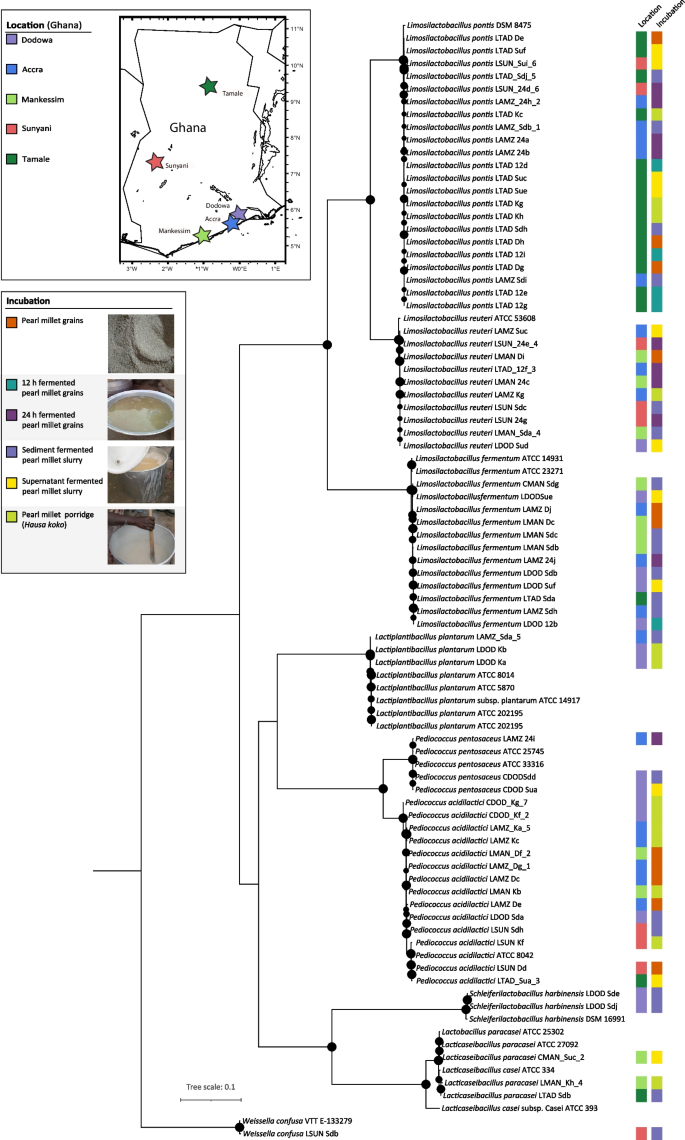

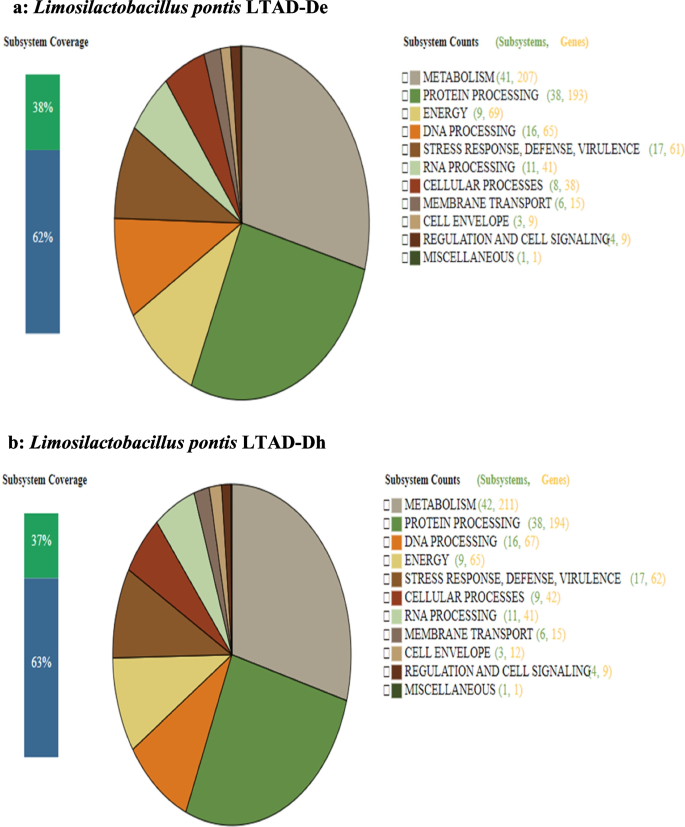

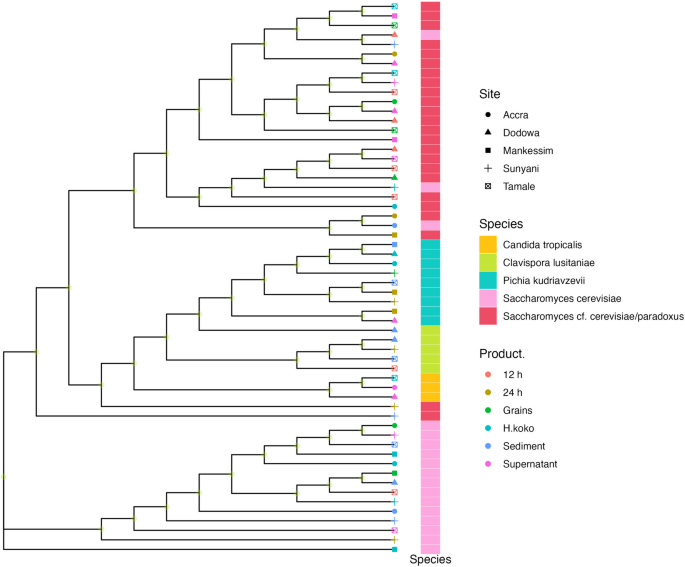

The predominant lactic acid bacteria and yeasts involved in the spontaneous fermentation of millet during the production of the traditional porridge Hausa koko in Ghana

- Amy Atter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6716-6748 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Maria Diaz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3423-9872 3 ,

- Kwaku Tano-Debrah 2 ,

- Angela Parry-Hanson Kunadu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8758-0420 2 ,

- Melinda J. Mayer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8764-2836 4 ,

- Lizbeth Sayavedra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5814-9471 4 ,

- Collins Misita 5 ,

- Wisdom Amoa-Awua 1 , 6 &

- Arjan Narbad 3 , 4

BMC Microbiology volume 24 , Article number: 163 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

45 Accesses

10 Altmetric

Metrics details